Abstract

Land application of compost has been a promising remediation strategy for soil health and environmental quality, but substantial emissions of greenhouse gases, especially N2O, need to be controlled during making and using compost of high N-load wastes, such as chicken manure. Biochar as a bulking agent for composting has been proposed as a novel approach to solve this issue, due to large surface area and porosity, and thus high ion exchange and adsorption capacity. Here, we compared the impacts of biochar-chicken manure co-compost (BM) and chicken manure compost (M) on soil biological properties and processes in a 120-d microcosm experiment at the soil moisture of 60% water-filled pore space. Our results showed that BM and M addition significantly enhanced soil total C and N, inorganic and KCl-extractable organic N, microbial biomass C and N, cellulase enzyme activity, abundance of N2O-producing bacteria and fungi, and gas emissions of N2O and CO2. However, compared to the M treatment, BM significantly reduced soil CO2 and N2O emissions by 35% and 27%, respectively, over the experimental period. The 15N-N2O site preference, i.e., difference between 15N-N2O in the center position (δ15Nα) and the end position (δ15Nβ), was ~17‰ for M and ~26‰ for BM during the first week of incubation, suggesting that BM suppressed N2O from bacterial denitrification and/or nitrifier denitrification. This inference was well aligned with the observation that soil glucosaminidase activity and nirK gene abundance were lower in BM than M treatment. Further, soil peroxidase activity was greater in BM than M treatment, implying soil organic C was more stable in BM treatment. Our data demonstrated that the biochar-chicken manure co-compost could substantially reduce soil N2O emissions compared to chicken manure compost, via controls on soil organic C stabilization and the activities of microbial functional groups, especially bacterial denitrifiers.

1. Introduction

Composting, a waste treatment technology, transforms organic material into stabilized compost, which can provide numerous benefits to soil fertility/quality and thus agricultural productivity (Chadwick et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2007; Lehmann et al., 2006). Land application of compost often enlarges the content of soil organic matter, promotes the formation of soil aggregates, and increases the availability of soil nutrients (Bacilio et al., 2003; Stamatiadis et al., 1999). It can also increase soil microbial biomass and the activity of enzymes involved in nutrient mobilization (Bedada et al., 2014; Hernández et al., 2014). Compost has been found to be as effective as synthetic fertilizers in supplying nutrients to crops and thus improving grain yields; yet, it is more cost-effective and environmentally-friendly (Ahmad et al., 2007; Leite et al., 2010).

However, some negative impacts can occur in the soil and environment during the preparation and application of compost (Chadwick et al., 2011; De Brito et al., 1995). Production of cattle feedlot manure compost, for example, can emit substantial amounts of greenhouse gases (e.g., CO2 and N2O) (Hao et al., 2004). By promoting soil nitrification and denitrification, various manures (pig slurry, poultry manure and farmyard manure) and their composts could also increase soil N2O emissions (Chadwick et al., 2011), and a study conducted by Rochette et al. (2008) even showed that land application of liquid and solid dairy manure led to more N2O emission over a longer period than the land application of synthetic fertilizers. As such, C and N losses during production and use of compost need to be controlled for improving agronomic value of compost and also for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions.

Using biochar as a bulking agent for composting has been proposed as a novel approach to solve the environmental trade-offs of compost (Sánchez-García et al., 2015; Steiner et al., 2010). Biochar, a biochemically-recalcitrant C-rich material that is made from biomass via pyrolysis, has been demonstrated to facilitate soil C sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions mitigation (Lehmann et al., 2006; Sohi et al., 2010). Both feedstock source and pyrolysis temperature can considerably affect the biochar bulk and surface properties; and as pyrolysis temperature increases, the amount of oxygenated surface functional groups can be greatly reduced (Suliman et al., 2016). Differences in biochar properties may affect the direction and magnitude of soil greenhouse gas emissions. For example, biochar C:N ratio has little influence on soil greenhouse gas emissions, but feedstock source, pyrolysis temperature and biochar pH can significantly affect soil CO2, CH4, and N2O fluxes after biochar amendment (He et al., 2017). Nonetheless, it is estimated that biochar may potentially abate the current annual rate of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions by 12% (Woolf et al., 2010). Biochar can also improve soil fertility and health via influences on soil physical structure, chemical properties and biological processes (Atkinson et al., 2010; Lehmann et al., 2011); and positive impacts have been attributed to biochar's bulk and surface properties, including surface area, porosity and sorption capacity (Lehmann et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2010).

Recently, we have made poultry litter compost using rice hull biochar as a bulking agent (Jia et al., 2016). Compared with composting without biochar, biochar-composting reduced the peak rate of N2O emissions by ~60% and increased inorganic N retention in final biochar-compost by ~70%. Our data, together with other research (Sánchez-García et al., 2015; Steiner et al., 2010) indicate that biochar can be an ideal bulking agent to minimize the adverse impacts of composting on the environment. However, there are few research detailing a full spectrum of impacts of biochar-manure compost on soil fertility/quality as well as greenhouse gas emission mitigation (Agegnehu et al., 2015). This study aimed to provide comprehensive assessment of soil C and N cycling processes, soil quality metrics including microbial biomass and enzyme activities, and population dynamics of soil microbial functional groups after soil amendments of biochar-chicken manure compost versus chicken manure compost.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Soil sampling

Soil samples were collected from the three field plots of an organic cropping system at the Center for Environmental Farming Systems (35°22′48″ N, 78°02′36″ W), Goldsboro, North Carolina, USA. Soil type was Tarboro loamy sand (mixed, thermic Typic Udipsamment; 73% sand, 26% silt, and 1% clay) in one plot and Wickham sandy loam (fine-loamy, mixed, semiactive, thermic Typic Hapludult; 58% sand, 34% silt, and 8% clay) in the other two plots. Information on plot size, fertilization, crop species, and farming management has been given previously (Tian et al., 2010). In June 2015, fifty soil cores (2.5 cm diameter × 10 cm height) were randomly collected from each plot and pooled, leading to total three composite soil samples. Soil was sieved (<2 mm) and then stored at 4 °C for about two weeks prior to microcosm experiments. On average, soil samples had a pH value of 6.5, and contained 13.5 mg total C g−1 soil and 1.3 mg total N g−1 soil.

2.2. Composting of chicken manure

Chicken manure, the mixture of manure and bedding materials, was collected from the poultry/chicken unit of the Department of Poultry Science at North Carolina State University (Raleigh, NC, USA), and was kept under ambient conditions for one-week air drying to lose excess moisture prior to composting.

Two types of composting were performed; one was the composting of chicken manure with the addition of hardwood sawdust at a sawdust/manure fresh weight ratio of 3:7, and the other was the composting of chicken manure with the addition of both hardwood sawdust and rice hull biochar at a biochar/sawdust/manure fresh weight ratio of 2:1:7. Here, the rice hull biochar was produced using low temperature gasification in an existing top-lit updraft gasifier (Jia et al., 2016), with pH 9.7, and containing 880.2 g total C kg−1 and 1.3 g total N kg−1.

The composting materials (~5 kg), together with 1 L deionized water were put into a 10 L plastic container which had several small holes on one end to allow gas, heat, and water vapor to exchange with the environment. The plastic container was then turned two to three times per day. This turning regime meant to keep composting materials in an aerated and fluffed state. After each turning, composting materials could reheat itself repeatedly and therefore turning sped up the composting process. The temperature of composting materials was monitored every day and followed 2 d meso-2 d thermo (50–60 °C)-3 d meso fluctuations during the 7 d composting process. The manure compost (M) and biochar-manure compost (BM) had pH 8.1 and 16.9 g total N kg−1; yet, the two differed in total C content, with 331.5 and 423.4 g C kg−1 for M and BM, respectively.

2.3. Laboratory microcosm setup

A 120-d laboratory incubation experiment was conducted to compare the impacts of M and BM addition on soil CO2 and N2O emissions as well as soil biochemical properties. There were four treatments, including (1) control (CK): soil without the addition of biochar, M, or BM, (2) biochar (B): soil with the addition of biochar at 1%, (3) BM: soil with the addition of BM at 5%, and (4) M: soil with the addition of M at 4%. These percentage amendments kept similar amounts of biochar for B and BM treatments as well as similar amounts of other compost ingredients for M and BM treatments. The four treatments were randomly assigned to each of three soils sampled from three field plots (i.e., 4 treatments × 3 blocks). Controls and compost-amended soils (~20 g dry weight equivalent) were packed into 120 ml specimen containers at a bulk density of 1.1 g cm−3, assuming that particle density was 2.65 g cm−3. Treatments were incubated at 60% water-filled pore space (WFPS), i.e., equivalent to 18.2–20.0% gravimetric soil water content and 45.5–50.0% soil water holding capacity, and room temperature (23 ± 2 °C). Soil moisture was maintained over the incubation by water addition. At each sampling time, 12 specimen containers representing four treatments and three blocks were randomly taken from a total of 120 specimen containers (i.e., 4 treatments × 3 blocks × 10 sampling times), and then soils were destructively sampled for the analysis of soil chemical and biological properties, soil enzyme activities, and the abundances of soil bacteria, fungi, and nitrous oxide producers. Except for placing soils (50 g dry weight equivalent) into 120-ml amber jars, the same treatments and incubation conditions were used to repeatedly measure N2O and CO2 fluxes and N isotope site preference (SP) of N2O over the incubation using a total of 12 amber jars (i.e., 4 treatments × 3 blocks).

2.4. Soil chemical and biological properties

Soil total C and N were determined by dry combustion method using a Perkin-Elmer 2400 CHN analyzer (Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Norwalk, CT, USA). Soil pH was measured in water with 1:2.5 soil (g)/water (ml) ratio. Soil inorganic N (NH4+-N and NO3−-N) was analyzed using a FIA QuikChem 8000 autoanalyzer (Lachat Instruments, Loveland, CO, USA) after extraction with 1M KCl or distilled water at 1:5 soil (g)/solution (ml) ratio and filtered through Whatman #42 filter papers. Extracted soil organic C (EOC) in 1M KCl or distilled water was measured using a TOC analyzer (TOC-5000, Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Japan). Extracted soil organic N (EON) was determined by the differences in inorganic N after and before potassium persulfate oxidation (Cabrera and Beare, 1993). Soil microbial biomass C and N were determined by the chloroform fumigation extraction method; and extraction coefficients are 0.38 and 0.54 for biomass C and N, respectively (Brookes et al., 1985; Vance et al., 1987). Soil C, N and pH were measured at the end of 120-d incubation, and soil microbial biomass C was measured at the beginning of 120-d incubation. Other soil properties, including inorganic N, EON, soil microbial biomass N, soil enzyme activities, and microbial abundances (i.e., quantitative real-time PCR analyses) were measured periodically (i.e., 0, 3, 7, 21, 28, 49, 63, 77, 91 and 120) over the incubation.

2.5. Soil enzyme activities

The activities of exoglucanase (EC 3.2.1.91), β-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.21), and β-glucosaminidase (EC 3.21.30) were determined using 2 mM p-nitrophenyl-β-D cellobioside, 10 mM p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, and 2 mM p-nitrophenyl N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide as the substrates, respectively (Tian and Shi, 2014). In short, soil slurries (0.8 ml) were pipetted into substrate-containing Eppendorf tubes and then incubated for 1–2 h at 37 °C. Here, soil slurry was made by adding ~3 g soil to 15 ml of acetate buffer (pH 5.0) and shaking at 200 rev. min−1 for 1 h. After reaction was terminated and color developed by adding 0.2 ml of 0.5 M CaCl2 and 0.8 ml of 0.5 M NaOH, suspension was centrifuged at ~11,700×g for 4 min. Then, supernatant with the product, p-nitrophenol, was pipetted into 96-well microplate for the measurement of optical density at 410 nm.

The activity of peroxidase was measured following the method of Johnsen and Jacobsen (2008). Soil slurries (0.2 ml) were pipetted into Eppendorf tubes that contained 0.4 ml of TMB (3,3′,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine) Easy solution (Fisher Scientific Inc.) and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Reaction was terminated by adding 0.8 ml of 0.3 M sulfuric acid followed by centrifuging at ~11,700 ×g for 4 min. The optical density of supernatant was measured at 450 nm.

The assay of each soil enzyme activity included two types of controls (i.e., substrate alone and soil alone). After subtracting the controls, hydrolyase activity was calculated against the standard curve of p-nitrophenol; and oxidase activity was calculated using the extinction coefficient, 59,000 M−1 cm−1. Cumulative enzyme activity over the incubation was used to compare treatment effects, which was calculated by the formula: Σn i = EiTi, where n is the number of incubation days, Ei is the mean enzyme activity of two successive measurements, and Ti is the time between the two measurements (Waring, 2013).

2.6. Quantitative real-time PCR

Impacts of M and BM on the abundance of soil bacteria, fungi and nitrous oxide producers were examined using a quantitative real-time PCR approach. Soil DNA was extracted, using a FastDNA SPIN kit (MP Bio, Solon, OH, USA), from ~0.8 g soil re-sampled from the microcosms as mentioned above. Soil DNA quality and size were checked by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel.

Quantitative real-time PCR (CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was performed on each soil DNA sample with three analytical replicates to determine the copy numbers of 16S rDNA, ITS (internal transcribed spacer) region of rDNA, bacterial nitrite reductase genes (nirS and nirK), ammonia monooxygenase (amoA) genes in ammonia oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia oxidizing bacteria (AOB), and fungal nitrite reductase gene nirK and nitric oxide reductase p450nor genes using the primers given in Table 1. These gene copy numbers were considered as the surrogates of the abundances of soil bacteria, fungi, bacterial denitrifiers, archaeal and bacterial nitrifiers, and fungal denitrifiers, respectively. A 20 µL qPCR reaction contained 4 µL of template DNA (0.2–0.6 ng µL-1), 10 µL 1X SsoAdvanced TM SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and 3 µL of each primer whose concentration was based on respective references (Table 1). All the qPCR reactions were initiated at 98 °C for 2 min, followed by a number of touchdown cycles and/or regular PCR cycles as specified in Table 1. The specificity of the qPCR reactions was determined by melting curve analysis (60 °C–95 °C) and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Table 1.

Primers and qPCR conditions for the real-time PCR quantifications of 16S rDNA, ITS region of rDNA, nirS, nirK, amoA in AOA and AOB, fungal nirK and P450nor genes extracted from variously treated soils.

| Target genes | Primers (sequences) and fragment sizea | qPCR conditionsb | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rDNA | F: Eub338 (ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG) | 40 CL: 98 °C for 10 s, 53 °C for 30 s, & 72 °C for 30 s | (Fierer et al., 2005) |

| R: Eub518 (ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG) | |||

| S: 200 bp | |||

| ITS | F: 5.8S (CGCTGCGTTCTTCATCG) | Same as 16S rDNA | (Fierer et al., 2005) |

| R: ITS1f (TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG) | |||

| S: 300 bp | |||

| nirS | F: nirSCd3aF (AACGYSAAGGARACSGG) | Six TD CL: 98 °C for 10 s, 63 °C for 30 s, & 72 °C for 30 s with AT dropped by 1 °C CL−1 to 58 °C | (Kandeler et al., 2006) |

| R: nirSR3cd (GASTTCGGRTGSGTCTTSAYGAA) | 40 CL: 98 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 30 s, & 72 °C for 30 s | ||

| S: 425 bp | |||

| nirK | F: nirK876 (ATYGGCGGVAYGGCGA) | Same as nirS | (Henry et al., 2004) |

| R: nirK1040 (GCCTCGATCAGRTTRTGGTT) | |||

| S: 165 bp | |||

| AOA amoA | F: CrenamoA23f (ATGGTCTGGCTWAGACG) | 40 CL: 98 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, & 72 °C for 30 s | (Tourna et al., 2008) |

| R: CrenamoA616r (GCCATCCATCTGTATGTCCA) | |||

| S: 625 bp | |||

| AOB amoA | F: amoA-1F (GGGGTTTCTACTGGTGGT) | 40 CL: 98 °C for 10 s, 56 °C for 30 s, & 72 °C for 30 s | (Rotthauwe et al., 1997) |

| R: amoA-2R (CCCCTCKGSAAAGCCTTCTTC) | |||

| S: 491 bp | |||

| Fungal nirK | F: FnirK_F3 (GCARAGCGAGTTYTACCAYG) | Same as AOB amoA | (Chen et al., 2016b) |

| R: FnirK_R2 (TVCCGATDAYRTGGAAYGARC) | |||

| S: 233 bp | |||

| P450nor | F: Fnor (DTTTGTYGAYATGGATSCYCC) | 40 CL: 98 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 30 s, & 72 °C for 30 s | Unpublished |

| R: Fnor (TCATGTTBACCATRGTNGCRT) | |||

| S: 643 bp |

F, R, and S stands for forward, reverse, and size, respectively.

CL, TD, AT are short for cycles, touchdown, and annealing temperature, respectively.

The standard curve for determining the gene copy number was made with the agarose gel-purified PCR products based upon the method of Zhang et al. (2011). Briefly, respective PCR products were run on a 1% low-melting agarose gel. Then, gel bands corresponding to the expected amplicon sizes were excised and DNA was extracted using a gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The DNA concentrations of extracted PCR products were quantified using a nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). Number of gene copies per µL of the PCR product (i.e., the standard) was calculated by the equation: (A × B)/(C × D), where A is the concentration of the PCR product (ng µL−1), B is the Avogadro number (i.e., 6.023 × 1023 molecules mol−1), C is the average molecular weight of a DNA base pair (i.e., 6.6 × 1011 ng mol−1), and D is the respective PCR amplicon size given in Table 1. Serial dilutions of PCR products of known copy numbers were amplified in triplicate together with samples. A standard curve was constructed by plotting the logarithm of the copy numbers against the mean threshold cycles.

2.7. Measurements of N2O and CO2 fluxes, and 15N-N2O site preference

Soil N2O and CO2 production were measured almost daily during a 7-week incubation. At each sampling event, amber jars were placed into closed 1-L PVC jars for two hours. Our preliminary experiment showed that headspace N2O and CO2 concentrations were a linear function of time during the two-hour period. The CO2 concentrations in the jars were determined using an infrared gas analyzer LI-840A (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). The N2O concentrations and N isotope site preference were analyzed using a dual quantum cascade laser (QCL) N2O measurement system (Model CWQCL-200-D, Aerodyne, Billerica, MA, USA). Information on QCL system setup has been given previously (Chen et al., 2016a). The QCL system measures N2O concentration as parts per billion of 14N in N2O. Gas fluxes (ng g−1 soil h−1) from the microcosm were calculated as: ((Csample-Cair) × M × V)/(r × m × t), where Csampleand Cair are the gas concentrations in the headspace of PVC jar and ambient air (ppbv), respectively; V is the volume of PVC jar headspace (cm3); M is the molar mass of gas (g mol−1); r is the molar volume at 23 °C and 1 atm. (24.29 L mol−1), m is the dry weight of soil (g), and t is the measuring time (h).

The QCL system was also used to determine the 15N SP of N2O to help identify the biological sources of soil N2O emissions (Chen et al., 2016a). The two N and one O atoms of N2O are structured linearly, resulting in two 15N isotopocules: 14N15N16O (15Nα) and 15N14N16O (15Nβ). The 15N-SP, i.e., the difference between δ15Nα and δ15Nβ has been found to be closely associated with biological processes, with 32.7‰ for bacterial NH4+ oxidation, 33.0‰ for bacterial NH2OH oxidation, −2.2‰ for bacterial denitrification, −1.0‰ for nitrifier denitrification, and 35.2‰ for fungal denitrification (Decock and Six, 2013). Higher SP values indicate the enrichment of 15N-N2O in center position. The QCL system provided the mixing ratio of the natural abundance of 15N in the center and edge position of N2O, i.e., 15Nα and 15Nβ, respectively. After normalized to total N2O-N concentration, these ratios were used to calculate the natural abundance of 15Nα and 15Nβ of N2O. Then, 15N SP and bulk 15N isotope ratio (δ15Nbulk) were estimated by the following equations: 15N SP = δ15Nα - δ15Nβ and δ15Nbulk = (δ15Nα + δ15Nβ)/2. It should be noted that δ15N-N2O could not be reliably estimated when the headspace N2O concentration was <700 ppb (Chen et al., 2016a). In this case, δ15Nbulk and 15N SP were not reported. During gas sample measurements by the QCL system, a standard gas (N2O = 50 ppm, δ15Nα(‰) = 3.95 ± 0.39, δ15Nβ (‰) = 1.83 ± 0.90) was included as a quality control.

To examine if M and BM differ in biological N2O formation pathways, we estimated the source partitioning of N2O, using a mass balance equation: SPtret = p•SP1 + (1-p)•SP2, where SPtret represents 15N-N2O SP for soil with compost amendment; SP1is 15N-N2O SP for biological processes with similar positive values around ~ 30‰, including bacterial and archael nitrification and fungal denitrification; SP2 is 15N-N2O SP for biological processes with similar negative values around ~ −1‰, including bacterial denitrification and nitrifier denitrification (Chen et al., 2016a; Decock and Six, 2013; Jung et al., 2014; Maeda et al., 2015; Sutka et al., 2006); and p is the percentage of combined N2O contributions from biological processes with positive SP values around ~ 30‰ (i.e., nitrification and fungal denitrification).

2.8. Data analysis

Because C and N contents differed between M and BM composts, we presented our data on a per compost-C or -N basis to better compare M and BM impacts. In brief, data obtained from controls at each sampling time were subtracted from data obtained from M and BM, and then the resulting data were divided by the amounts of added compost C or N. Here, the average values of soil alone and soil with 1% biochar addition were used for subtraction, because all measurements were not different between the two controls at each sampling time. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of a completely randomized block design (SAS 9.3, SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA) was used to assess significant differences in soil total C and N contents, C:N ratios, soil pH, and cumulative enzyme activities between M and BM treatments. In addition, ANOVA of a split plot design with treatments as the whole-plot factor and sampling times as the split-plot factor was used to evaluate significant differences in soil microbial biomass N between M and BM treatments. We also used ANOVA of a completely randomized block design with repeated measures to test the differences in soil N2O and CO2 production rates, site-preference (SP), and δ15NBulk between M and BM treatments. In this study, treatments were deemed significant at P < 0.05. Significant levels other than P < 0.05 are given directly in the results.

3. Results

3.1. Soil chemical and microbial properties

BM and M addition significantly increased total soil C and N, but decreased soil pH compared to control soil or soil with 1% biochar addition (Table 2). Soil total C was greater in BM-than M-amended soil, as was the soil C:N ratio.

Table 2.

Selected soil chemical and microbial properties in control soil (CK) and soil with the addition of biochar (B), biochar-manure compost (BM), and manure compost (M). Chemical and microbial properties were measured at the end and beginning of 120-d incubation, respectively.a

| Soil C | Soil N | Soil C:N | Soil pH | MBC | MBN | MB C:N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| mg C or N g−1 soil | µg C or N g−1 soil | ||||||

| CK | 12.6 c | 1.2 b | 10.9 b | 6.4 a | 155.4 b | 35.5 c | 4.5 c |

| B | 13.4 c | 1.2 b | 11.2 b | 6.3 a | 174.5 b | 36.4 c | 5.1 c |

| BM | 28.5 a | 2.2 a | 12.7 a | 5.9 b | 486.9 a | 45.1 b | 11.3 a |

| M | 21.3 b | 2.1 a | 10.0 b | 5.9 b | 526.6 a | 59.6 a | 8.8 b |

A Different letters within a column indicate significant differences of means, n = 3 at P < 0.05. MB denotes microbial biomass.

Following BM and M addition, soil microbial biomass C, N and C:N ratio increased significantly. Microbial biomass N also differed significantly between BM- and M-amended soil, and as a result, microbial biomass C:N ratio was greater in BM-than M-amended soil. However, the difference in microbial biomass N between BM- and M-amended soils only maintained for a couple of days and, thereafter, microbial biomass N was similar for BM- and M-amended soils over the incubation (data not shown).

3.2. Soil N availability

Extractants (1M KCl and water) did not affect the measurements of inorganic N and EON (data not shown); therefore only data obtained using 1M KCl were reported. Soil inorganic N concentrations increased significantly following BM and M addition and peaked around the 3rd week of the incubation (Fig. 1A). Soil NO3− was the major species of inorganic N, as it was at least 3 times greater than soil NH4+ during the incubation (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Changes in soil inorganic N (A) and extractable organic N (B) over time following BM and M addition. Insert figures represent net N mineralization and net change of extractable organic N at the end and beginning of incubation, respectively. Data were normalized by the amount of N addition in BM and M, respectively, after subtracting data of controls (i.e., CK and B). Error bars are standard error for n = 3; symbol * denotes significant differences at P < 0.05.

Soil EON concentrations increased immediately by the addition of BM and M, and then decreased over time (Fig. 1B). At the end of incubation, EON in BM- and M-amended soil was back to the level of controls. However, at some time points (d 28 and 49), EON was considerably greater in M-amended soil than BM-amended soil.

Net N mineralization increased significantly from ~40 µg N g−1 soil in controls to ~115 µg N g−1 in M- and BM-amended soil, but there was no significant difference between M and BM. Similarly, there was no difference between M and BM in the net change of EON at the end and beginning of incubation. On the basis of N addition, net N mineralization was ~110 mg g−1 added N, and net change of EON was ~200 mg g−1 added N.

3.3. Soil enzyme activities

In general, BM and M addition stimulated the activities of soil exoglucanase, β-glucosidase, and β-glucosaminidase, but inhibited soil peroxidase activity (Fig. 2). However, the magnitude and dynamic pattern of stimulation and/or inhibition varied with individual enzymes. Stimulation effects were greater and longer for soil β-glucosidase and β-glucosaminidase than for soil exoglucanase. The peak activity was around d 7 for soil exoglucanase, β-glucosidase, β-glucosaminidase, but on d 0 for soil peroxidase.

Fig. 2.

Changes in the activities of soil exglucanase, β-glucosidase, β-glucosaminidase, and peroxidase over the incubation following BM and M addition. Data were normalized by the amount of C addition in BM and M, respectively, after subtracting data of controls (i.e., CK and B). Error bars are standard error for n = 3; symbol * denotes significant differences at P < 0.05.

Cumulative enzyme activities of exoglucanase and β-glucosidase were similar for BM- and M-amended soils, but the cumulative β-glucosaminidase activity was marginally greater in M than BM (P < 0.1) (Fig. 3). By contrast, the cumulative peroxidase activity was significantly lower in M-than BM-amended soil (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Changes in the cumulative activities of soil exglucanase, β-glucosidase, β-glucosaminidase, and peroxidase over the incubation following BM and M addition. Data were normalized by the amount of C addition in BM and M, respectively, after subtracting data of controls (i.e., CK and B). Error bars are standard error for n = 3; symbol * denotes significant differences at P < 0.05.

3.4. Quantitative real-time PCR

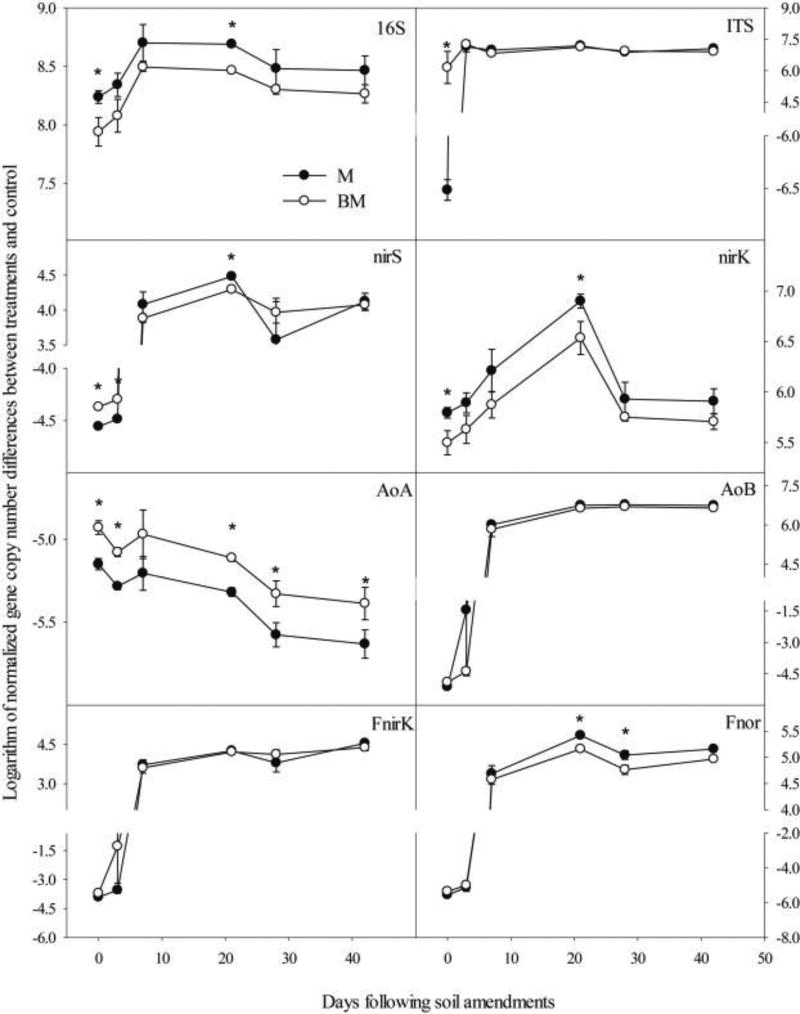

Following BM and M addition, soil 16S and ITS gene abundance increased significantly, except for ITS on d 0 in M-amended soil (Fig. 4A and B). Bacterial nirS and nirK abundance were also greater in BM- and M-amended soil than those in controls, except for nirS during the first 3 d (Fig. 4C and D). However, the amoAabundance of AOA and AOB responded differently to BM and M addition. AOA amoAabundance reduced significantly after BM and M addition, whereas AOB amoAabundance was greater in BM- and M-amended soil than controls, except for the first 3 d (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4E and F). Fungal nirK and p450nor abundance were also enhanced by the addition of BM and M except for the first 3 d (Fig. 4G and H).

Fig. 4.

Changes in the gene abundances of 16S (A), ITS (B), nirS (C), nirK (D), AOA amoA (E), AOB amoA (F), Fungal nirK (G), and Fungal p450nor (F) following BM and M addition over the incubation. Data were normalized by the amount of C addition in BM and M, respectively, after subtracting data of controls (i.e., CK and B). Error bars are standard error for n = 3; symbol * denotes significant differences at P < 0.05.

Effects of BM and M on 16S, nirK and AOA amoA abundance differed significantly over the entire period of incubation (Fig. 4A, D, E). Compared to BM, M showed stronger stimulation effects on 16S and nirK abundance, but stronger inhibition effects on AOA amoA abundance.

3.5. The N2O and CO2 fluxes, and N isotope site-preference

Soil N2O emissions in controls were about 12.5 ng N2O g−1 soil during 7-week incubation. Following BM and M addition, however, soil N2O emissions increased by > 330 times to 4.2–4.5 µg N2O g−1 soil. On the basis of total N addition, N2O-peak flux rates in BM were significantly lower than those in M addition; as a result, cumulative N2O emissions were 27% lower in BM than M addition (Fig. 5A). Following BM and M addition, soil CO2 emissions also increased significantly from ~4.2 mg g−1soil in controls to ~18.4 mg g−1 soil in BM and M-amended soil. On the basis of total C addition, CO2-peak flux rates were significantly lower in BM than M addition, and correspondingly cumulative CO2 emissions over 46-d incubation were ~35% lower in BM than M (Fig. 5B). This amount of CO2-C efflux reduction (i.e., ~150 mg CO2-C per 20 g soil-compost mixture) was equivalent to the amount of C loss during the formation of amended biochar (i.e., 0.2 g biochar with ~50% loss of biomass C during biochar formation).

Fig. 5.

Changes in soil N2O (A) and CO2 (B) fluxes following BM and M addition. Insert figures represent changes in cumulative N2O and CO2 emissions over the incubation, respectively. Data were normalized by the amount of N addition for N2O and by the amount of C addition for CO2 in BM and M, respectively, after subtracting data of controls (i.e., CK and B). Error bars are standard error for n = 3; symbol * denotes significant differences at P < 0.05.

15N-N2O site preference could be reliably estimated when N2O flux rates were >8.0 µg g−1 added N h−1, corresponding to the incubation period of d 2 to 7. The δ15Nbulk varied largely from −9.2–8.3‰ over time and were similar for BM and M addition, except for measurements on d 4 (Fig. 6b). The 15N-N2O site preference (SP) also fluctuated over time in the range of 9.9–32.6‰, but it was consistently higher in BM-than in M-amended soil (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

15N isotope site preference (SP) (A) and δ15NBulk of N2O (B) in BM- and M-amended soil. Error bars are standard error for n = 3; symbol * denotes significant differences at P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

With the presumption that biochar could help stabilize N during manure composting, we expected that BM could lower N mineralization and N2O emission more than M. Also, differences in C and N biochemistry between BM and M, e.g., organic matter content and stability might cause changes in microbial allocation of resource for generating extracellular enzymes for C and N acquisition. Furthermore, the abundances of microbial communities involved in organic matter degradation and N transformations were expected to diverge between BM and M. Our data strongly supported these speculations, except for N mineralization, which appeared to be similar between BM and M.

4.1. Nitrogen availability and loss

The major forms of N in BM and M were organic N in solid phase, KCl-extractable organic N (EON), and inorganic N. Inorganic N accounted for ~2% of total N, whereas KCl-extractable organic N was ~20% of total N. Such a stoichiometry has been reported in other types of compost (Said-Pullicino et al., 2007).

EON has been considered as a good metric for predicting N mineralization (Ros et al., 2011). As expected, when EON declined over time, inorganic N increased. However, N mineralization, i.e., the net change of inorganic N at the end and beginning of the incubation, was only ~50% of the net change of EON in both BM and M, suggesting that EON was transformed into other N pools besides inorganic N. It was possible that microbes degraded EON and then incorporated available N into the biomass. Subsequently, as microbial biomass turned over, biomass N was stabilized into soil organic N. There is increasing evidence that microbial biomass residues are an important source of soil organic matter (Dijkstra et al., 2006; Kallenbach et al., 2016; Miltner et al., 2012). EON could also be stabilized into soil organic N through chemical processes, such as adsorption and condensation. It was also possible that EON was lost through sequential microbial processes of mineralization, nitrification and denitrification in hot spots. The observations that EON was greater in M than BM during some time points of incubation, but the net change of EON at the end and beginning of incubation was similar between M and BM further suggested biochemical transformations/translocations of EON into other N pools, and also greater potentials of N loss in M than BM.

Indeed, N2O emissions in M were substantially larger than those in BM. Biochar has been demonstrated to be able to cut off soil N2O emissions in both field and laboratory investigations (Cayuela et al., 2013; Rondon et al., 2007; Spokas and Reicosky, 2009; Yanai et al., 2007b). In the present study, soil N2O emissions were monitored under presumed aerobic conditions, i.e., 60% WFPS. However, denitrification might still occur in organic-C rich hot spots due to rapid O2 depletion via microbial respiration. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the roles of biochar in mitigating N2O emissions via denitrification, including biochar toxicity, aeration regulation, NO3− immobilization and liming effects. While the high porosity of biochar may enhance the supply and distribution of O2, changes in aeration appeared to have little influence on N2O emissions mitigation (Case et al., 2012; Cayuela et al., 2013). Liming effects on N2O emissions mitigation were also controversial (Hüppi et al., 2015; Obia et al., 2015), and so was biochar toxicity. Recently, Cayuela et al. (2013) has proposed a new theory to explain biochar effects on mitigating N2O emissions via denitrification. In this hypothetical framework, biochar has been emphasized as a reducing agent due to containing redox-reactive Mn (IV) and Fe (III) to compete with NO3− and thereby reducing denitrification as well as an electron conduit associated with biochar-liming effect to promote N2O reductase for conversion to N2. Nonetheless, it is still a challenge to generalize biochar mitigation mechanisms because of large variations in biochar characteristics and hence biochar-soil interactions.

Biochar mitigation effects may also relate to N2O formation pathways (Sánchez-García et al., 2014). It is well known that several biological processes contribute to N2O emissions, including prokaryotic-mediated ammonium oxidation, nitrifier-denitrification, and denitrification. Recently, fungal denitrification has also been recognized as an important source of N2O emissions (Chen et al., 2014; Crenshaw et al., 2008; Laughlin and Stevens, 2002; Yanai et al., 2007a). Could the differences in N2O emissions between M and BM be caused by shifts in biological N2O formation pathways? To address this question, we estimated the source partitioning of N2O, using a mass balance equation in section 2.7. Using the average SP during d 2 to 7, ~17‰ for M and ~26‰ for BM, nitrification and fungal denitrification contributed ~58% and 73% of total N2O emissions for M and BM, respectively. This also suggested that BM suppressed bacterial denitrification and nitrifier denitrification.

The “N2O formation pathways change” supposition appeared to be further supported by the changes in the abundances of microbial communities involved in nitrification and denitrification. The lower abundance in BM than M of nirK, a gene encoding bacterial copper nitrite reductase for catalyzing nitrite reduction to NO during bacterial denitrification and nitrifier denitrification (Lawton et al., 2013), was well aligned with the lower contribution in BM than M of the two processes to N2O emissions. Others (Li et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2014) also found that biochar could suppress nirK or nirS gene abundances and hence N2O emissions. Of all the genes for encoding enzymes for bacterial nitrification, archaeal nitrification, and fungal denitrification, only archaeal amoA differed consistently between BM and M, suggesting that archaeal nitrification might be the main cause for observed differences in 15N-SP of N2O between BM and M. In fact, greater abundance of archaeal amoA in BM than M coincided with greater N2O contribution by combined nitrification and fungal denitrification in BM than M.

However, we need to stress that the differences in 15N-SP of N2O between BM and M could also be caused by N2O reduction. Isotope fractionation during N2O reduction to N2 can enrich 15N at the α position of N2O and therefore increase SP (Wu et al., 2016). Biochar has been found to be able to stimulate nosZ, a gene encoding N2O reductase for N2O conversion to N2 (Harter et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2014). A recent study by Wang et al. (2013) showed that biochar as a bulking agent during manure compost could reduce nirK abundance, but increase nosZ abundance and thus N2O emissions mitigation by biochar-manure composting was likely due to biochar effects on inhibiting N2O production and simultaneously increasing N2O consumption. Although our experiment was conducted under overall aerobic conditions, N2 might also be generated at organic C-rich microsites due to O2 depletion caused by microbial respiration. If so, we might overestimate the contribution of nitrification and fungal denitrification to N2O, specifically in BM.

4.2. Soil health improvement by BM versus M

Organic C is one of the biological properties used for assessing soil health. While both BM and M increased soil organic C content, BM effects were more substantial, perhaps because BM contained greater and more stable organic C than M. Biochar is known to resist biological degradation and therefore enhance soil carbon sequestration (Lehmann et al., 2006). For example, despite that biochar stability varied with pyrolysis material and conditions, the mean residence time of biochar in soil can range from several years to decades (Steinbeiss et al., 2009). In this study, biochar applied with BM was equivalent to 1% of soil mass and this small percentage of biochar addition appeared not to increase soil organic C significantly. However, compared with M, BM significantly increased soil organic C content by ~27% as measured at the end of incubation. Our results suggested that biochar might interact with organic C in manure, rendering organic C more stable during composting. Several recent studies have pointed out the role of biochar in stimulating the stabilization of organic material during composting. Using biochar as a bulking agent for the composting of poultry manure has been found to increase humic-like substances and meanwhile reduce water soluble C (Dias et al., 2010; Jindo et al., 2012) possibly due to sorption and stabilization of labile C compounds from microbial necromass.

Differences in the stability and chemical composition of organic matter can be manifested by changes of soil enzyme activities (Shi et al., 2006). As a cost-effective entity, the soil microbial community often generates extracellular enzymes that help achieve maximum benefits, i.e., available C and nutrients from the environment (Shi, 2010). Peroxidase is an enzyme involved in depolymerization and/or degradation of recalcitrant substances, such as lignin and phenolic compounds. Because C and energy return efficiencies are substantially lower from microbial degradation of recalcitrant substances than from degradation of carbohydrates, it is expected that microbial community would allocate resources to prioritize the production of cellulase over peroxidase if carbohydrates are present in the environment. This explains why we observed the lower peroxidase activity and greater activities of exoglucanase and glucosidase in BM and M compared to soil alone. Further, the greater activity of peroxidase in BM than M implied that BM contained more recalcitrant and stable organic C than M. Other biological properties examined in this study also indicated that BM might favor greater soil C accumulation than M. Microbial CO2 respiration was shown to be lower in BM than M, but fungal-to-bacterial ratio was higher in BM than M. Fungal dominance has been associated with large soil C storage, although the cause-effect relationships are complex (Bailey et al., 2002; Strickland and Rousk, 2010).

4.3. Conclusions

The positive impacts of compost on sustaining soil quality and improving nutrient supply have been well documented in literature. Despite different bulking materials used for composting between M and BM, both composts were proven to be effective for improving short-term soil available N, microbial biomass and activity, and the potential of hydrolytic enzymes for degrading organic matter. This work also revealed that both composts could considerably enlarge the population of soil N2O-producing fungi over a short term. However, compared with M, BM significantly reduced peak soil N2O emissions following soil amendment and improved soil organic C stabilization. Further, reduction in soil CO2 effluxes caused by BM over M during the short-term incubation appeared to be able to offset C loss during biochar formation. Because biochar aging can alter its physical and chemical properties, thereby affecting fundamental characteristics of “fresh” biochar, caution should be taken in extrapolating short-term effects of BM versus M to long-term impacts.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by USDA-NIFA#2011-67019-30189 and US-EPA ORD. Dr. Yinghong Yuan was also supported by the China Scholarship Council and the National Natural Science Foundation of China #41461050. We thank Dr. Joachim Mohn from EMPA for QCL calibration. Although this work was reviewed by EPA and approved for publication, it may not necessarily reflect official agency policy. Thanks also go to two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

References

- Agegnehu G, Bass AM, Nelson PN, Muirhead B, Wright G, Bird MI. Biochar and biochar-compost as soil amendments: effects on peanut yield, soil properties and greenhouse gas emissions in tropical North Queensland, Australia. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2015;213:72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad R, Jilani G, Arshad M, Zahir ZA, Khalid A. Bio-conversion of organic wastes for their recycling in agriculture: an overview of perspectives and prospects. Annals of Microbiology. 2007;57:471–479. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson CJ, Fitzgerald JD, Hipps NA. Potential mechanisms for achieving agricultural benefits from biochar application to temperate soils: a review. Plant and Soil. 2010;337:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bacilio M, Vazquez P, Bashan Y. Alleviation of noxious effects of cattle ranch composts on wheat seed germination by inoculation with Azospirillum spp. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 2003;38:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey VL, Smith JL, Bolton H. Fungal-to-bacterial ratios in soils investigated for enhanced C sequestration. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2002;34:997–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Bedada W, Karltun E, Lemenih M, Tolera M. Long-term addition of compost and NP fertilizer increases crop yield and improves soil quality in experiments on smallholder farms. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2014;195:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes PC, Landman A, Pruden G, Jenkinson D. Chloroform fumigation and the release of soil nitrogen: a rapid direct extraction method to measure microbial biomass nitrogen in soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1985;17:837–842. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera M, Beare M. Alkaline persulfate oxidation for determining total nitrogen in microbial biomass extracts. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 1993;57:1007–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Case SD, McNamara NP, Reay DS, Whitaker J. The effect of biochar addition on N2O and CO2 emissions from a sandy loam soilethe role of soil aeration. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2012;51:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cayuela ML, Sanchez-Monedero MA, Roig A, Hanley K, Enders A, Lehmann J. Biochar and denitrification in soils: when, how much and why does biochar reduce N2O emissions? Scientific Reports 3. 2013 doi: 10.1038/srep01732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick D, Sommer S, Thorman R, Fangueiro D, Cardenas L, Amon B, Misselbrook T. Manure management: implications for greenhouse gas emissions. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 2011;166:514–531. [Google Scholar]

- Chan KY, Van Zwieten L, Meszaros I, Downie A, Joseph S. Agronomic values of greenwaste biochar as a soil amendment. Soil Research. 2007;45:629–634. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Mothapo NV, Shi W. The significant contribution of fungi to soil N2O production across diverse ecosystems. Applied Soil Ecology. 2014;73:70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Williams D, Walker JT, Shi W. Probing the biological sources of soil N2O emissions by quantum cascade laser-based 15N isotopocule analysis. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2016a;100:175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Yu F, Shi W. Detection of N2O-producing fungi in environment using nitrite reductase gene (nirK)-targeting primers. Fungal Biology. 2016b;120:1479–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw C, Lauber C, Sinsabaugh R, Stavely L. Fungal control of nitrous oxide production in semiarid grassland. Biogeochemistry. 2008;87:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- De Brito A, Gagne S, Antoun H. Effect of compost on rhizosphere microflora of the tomato and on the incidence of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1995;61:194–199. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.194-199.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decock C, Six J. How reliable is the intramolecular distribution of 15N in N2O to source partition N2O emitted from soil? Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2013;65:114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Dias BO, Silva CA, Higashikawa FS, Roig A, Sanchez-Monedero MA. Use of biochar as bulking agent for the composting of poultry manure: effect on organic matter degradation and humification. Bioresource Technology. 2010;101:1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P, Ishizu A, Doucett R, Hart SC, Schwartz E, Menyailo OV, Hungate BA. 13C and 15N natural abundance of the soil microbial biomass. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2006;38:3257–3266. [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N, Jackson JA, Vilgalys R, Jackson RB. Assessment of soil microbial community structure by use of taxon-specific quantitative PCR assays. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71:4117–4120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.4117-4120.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao X, Chang C, Larney FJ. Carbon, nitrogen balances and greenhouse gas emission during cattle feedlot manure composting. Journal of Environmental Quality. 2004;33:37–44. doi: 10.2134/jeq2004.3700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter J, Krause H-M, Schuettler S, Ruser R, Fromme M, Scholten T, Kappler A, Behrens S. Linking N2O emissions from biochar-amended soil to the structure and function of the N-cycling microbial community. The ISME Journal. 2014;8:660–674. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Zhou X, Jiang L, Li M, Du Z, Zhou G, Shao J, Wang X, Xu Z, Bai SH, Wallace H, Xu G. Effects of biochar applicaion on soil greenhouse gas fluxes: a meta-analysis. Global Change Bilogy Bioenergy. 2017;9:743–755. [Google Scholar]

- Henry S, Baudoin E, Lopez-Gutierrez JC, Martin-Laurent F, Brauman A, Philippot L. Quantification of denitrifying bacteria in soils by nirK gene targeted real-time PCR. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2004;59:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez T, Chocano C, Moreno J-L, García C. Towards a more sustainable fertilization: combined use of compost and inorganic fertilization for tomato cultivation. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2014;196:178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hüppi R, Felber R, Neftel A, Six J, Leifeld J. Effect of biochar and liming on soil nitrous oxide emissions from a temperate maize cropping system. The Soil. 2015;1:707–717. [Google Scholar]

- Jia X, Wang M, Yuan W, Shah S, Shi W, Meng X, Ju X, Yang B. N2O emission and nitrogen transformation in chicken manure and biochar CoComposting. Transactions of the ASABE. 2016;59:1277–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Jindo K, Suto K, Matsumoto K, García C, Sonoki T, Sanchez-Monedero MA. Chemical and biochemical characterisation of biochar-blended composts prepared from poultry manure. Bioresource Technology. 2012;110:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.01.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen AR, Jacobsen OS. A quick and sensitive method for the quantifi- cation of peroxidase activity of organic surface soil from forests. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2008;40:814–821. [Google Scholar]

- Jung M-Y, Well R, Min D, Giesemann A, Park S-J, Kim J-G, Kim S-J, Rhee S-K. Isotopic signatures of N2O produced by ammonia-oxidizing archaea from soils. The ISME Journal. 2014;8:1115–1125. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenbach CM, Frey SD, Grandy AS. Direct evidence for microbialderived soil organic matter formation and its ecophysiological controls. Nature Communications. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandeler E, Deiglmayr K, Tscherko D, Bru D, Philippot L. Abundance of narG, nirS, nirK, and nosZ genes of denitrifying bacteria during primary successions of a glacier foreland. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72:5957–5962. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00439-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin RJ, Stevens RJ. Evidence for fungal dominance of denitrification and codenitrification in a grassland soil. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 2002;66:1540–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton TJ, Bowen KE, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Arp DJ, Rosenzweig AC. Characterization of a nitrite reductase involved in nitrifier denitrification. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:25575–25583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.484543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J, Gaunt J, Rondon M. Bio-char sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems e a review. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. 2006;11:395–419. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J, Rillig MC, Thies J, Masiello CA, Hockaday WC, Crowley D. Biochar effects on soil biotaea review. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2011;43:1812–1836. [Google Scholar]

- Leite LF, Oliveira FC, Araújo AS, Galv~ ao SR, Lemos JO, Silva EF. Soil organic carbon and biological indicators in an Acrisol under tillage systems and organic management in north-eastern Brazil. Soil Research. 2010;48:258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Song L, Jin Y, Liu S, Shen Q, Zou J. Linking N2O emission from biochar-amended composting process to the abundance of denitrify (nirK and nosZ) bacteria community. AMB Express. 2016;6:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13568-016-0208-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Shen G, Sun M, Cao X, Shang G, Chen P. Effect of biochar on nitrous oxide emission and its potential mechanisms. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 2014;64:894–902. doi: 10.1080/10962247.2014.899937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Spor A, Edel-Hermann V, Heraud C, Breuil M-C, Bizouard F, Toyoda S, Yoshida N, Steinberg C, Philippot L. N2O production, a widespread trait in fungi. Scientific Reports. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep09697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltner A, Bombach P, Schmidt-Brücken B, K€ astner M. SOM genesis: microbial biomass as a significant source. Biogeochemistry. 2012;111:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Obia A, Cornelissen G, Mulder J, Dorsch P. Effect of soil pH increase by € biochar on NO, N2O and N2 production during denitrification in acid soils. PloS One. 2015;10:e0138781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochette P, Angers DA, Chantigny MH, Gagnon B, Bertrand N. N2O fluxes in soils of contrasting textures fertilized with liquid and solid dairy cattle manures. Canadian Journal of Soil Science. 2008;88:175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rondon MA, Lehmann J, Ramírez J, Hurtado M. Biological nitrogen fixation by common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) increases with bio-char additions. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 2007;43:699–708. [Google Scholar]

- Ros GH, Hanegraaf MC, Hoffland E, van Riemsdijk WH. Predicting soil N mineralization: relevance of organic matter fractions and soil properties. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2011;43:1714–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Rotthauwe J-H, Witzel K-P, Liesack W. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1997;63:4704–4712. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4704-4712.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said-Pullicino D, Erriquens FG, Gigliotti G. Changes in the chemical characteristics of water-extractable organic matter during composting and their influence on compost stability and maturity. Bioresource Technology. 2007;98:1822–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-García M, Alburquerque J, Sanchez-Monedero M, Roig A, Cayuela M. Biochar accelerates organic matter degradation and enhances N mineralisation during composting of poultry manure without a relevant impact on gas emissions. Bioresource Technology. 2015;192:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-García M, Roig A, Sanchez-Monedero MA, Cayuela ML. Biochar increases soil N2O emissions produced by nitrification-mediated pathways. Frontiers in Environmental Science. 2014;2:25. [Google Scholar]

- Shi W. Agricultural and Ecological Significance of Soil Enzymes: Soil Carbon Sequestration and Nutrient Cycling, Soil Enzymology. Springer; 2010. pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Shi W, Dell E, Bowman D, Iyyemperumal K. Soil enzyme activities and organic matter composition in a turfgrass chronosequence. Plant and Soil. 2006;288:285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Singh BP, Hatton BJ, Singh B, Cowie AL, Kathuria A. Influence of biochars on nitrous oxide emission and nitrogen leaching from two contrasting soils. J. Environ. Qual. 2010;39:1224–1235. doi: 10.2134/jeq2009.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohi SP, Krull E, Lopez-Capel E, Bol R. Chapter 2-a review of biochar and its use and function in soil. In: Donald LS, editor. Advances in Agronomy. Academic Press; 2010. pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- Spokas KA, Reicosky DC. Impacts of sixteen different biochars on soil greenhouse gas production. Annals of Environmental Science. 2009;3:4. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatiadis S, Werner M, Buchanan M. Field assessment of soil quality as affected by compost and fertilizer application in a broccoli field (San Benito Country, California) Applied Soil Ecology. 1999;12:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbeiss S, Gleixner G, Antonietti M. Effect of biochar amendment on soil carbon balance and soil microbial activity. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2009;41:1301–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner C, Das K, Melear N, Lakly D. Reducing nitrogen loss during poultry litter composting using biochar. Journal of Environmental Quality. 2010;39:1236–1242. doi: 10.2134/jeq2009.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland MS, Rousk J. Considering fungal: bacterial dominance in soilsemethods, controls, and ecosystem implications. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2010;42:1385–1395. [Google Scholar]

- Suliman W, Harsh JB, Abu-Lail NI, Fortuna A-M, Dallmeyer I, Garcia-Perez M. Influence of feedstock source and pyrolysis temperature on biochar bulk and surface properties. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2016;84:37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sutka RL, Ostrom N, Ostrom P, Breznak J, Gandhi H, Pitt A, Li F. Distinguishing nitrous oxide production from nitrification and denitrification on the basis of isotopomer abundances. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72:638–644. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.638-644.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Dell E, Shi W. Chemical composition of dissolved organic matter in agroecosystems: correlations with soil enzyme activity and carbon and nitrogen mineralization. Applied Soil Ecology. 2010;46:426–435. [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Shi W. Soil peroxidase regulates organic matter decomposition through improving the accessibility of reducing sugars and amino acids. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 2014;50:785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Tourna M, Freitag TE, Nicol GW, Prosser JI. Growth, activity and temperature responses of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in soil microcosms. Environmental Microbiology. 2008;10:1357–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance E, Brookes P, Jenkinson D. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1987;19:703–707. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Lu H, Dong D, Deng H, Strong P, Wang H, Wu W. Insight into the effects of biochar on manure composting: evidence supporting the relationship between N2O emission and denitrifying community. Environmental Science & Technology. 2013;47:7341–7349. doi: 10.1021/es305293h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring BG. Exploring relationships between enzyme activities and leaf litter decomposition in a wet tropical forest. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2013;64:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf D, Amonette JE, Street-Perrott FA, Lehmann J, Joseph S. Sustainable biochar to mitigate global climate change. Nature Communications. 2010;1:56. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Koster JR, Cardenas LM, Brüggemann N, Lewicka-Szczebak D, Bol R. N2O source partitioning in soils using 15N site preference values corrected for the N2O reduction effect. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2016;30:620–626. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H-J, Wang X-H, Li H, Yao H-Y, Su J-Q, Zhu Y-G. Biochar impacts soil microbial community composition and nitrogen cycling in an acidic soil planted with rape. Environmental Science & Technology. 2014;48:9391–9399. doi: 10.1021/es5021058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanai Y, Toyota K, Morishita T, Takakai F, Hatano R, Limin SH, Darung U, Dohong S. Fungal N2O production in an arable peat soil in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2007a;53:806–811. [Google Scholar]

- Yanai Y, Toyota K, Okazaki M. Effects of charcoal addition on N2O emissions from soil resulting from rewetting air-dried soil in short-term laboratory experiments. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2007b;53:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Parameswaran P, Badalamenti J, Rittmann BE, Krajmalnik-Brown R. Integrating high-throughput pyrosequencing and quantitative real-time PCR to analyze complex microbial communities. In: Kwon YM, Ricke SC, editors. High-throughput Next Generation Sequencing. Springer; 2011. pp. 107–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]