Abstract

Objective

Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) is a powerful tool to investigate the neural mechanisms of perception and can be used to restore sensation for patients who have lost it. While sensitivity to ICMS has previously been characterized, no systematic framework has been developed to summarize the detectability of individual ICMS pulse trains or the discriminability of pairs of pulse trains.

Approach

We develop a simple simulation that describes the responses of a population of neurons to a train of electrical pulses delivered through a microelectrode. We then perform an ideal observer analysis on the simulated population responses to predict the behavioral performance of non-human primates in ICMS detection and discrimination tasks.

Main results

Our computational model can predict behavioral performance across a wide range of stimulation conditions with high accuracy (R2 = 0.97) and generalizes to novel ICMS pulse trains that were not used to fit its parameters. Furthermore, the model provides a theoretical basis for the finding that amplitude discrimination based on ICMS violates Weber's law.

Significance

The model can be used to characterize the sensitivity to ICMS across the range of perceptible and safe stimulation regimes. As such, it will be a useful tool for both neuroscience and neuroprosthetics.

Introduction

Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) has proven to be a useful tool to explore the neural mechanisms of behavior [1] and has yielded important insights into visual [2-4], auditory [5, 6], and tactile [7-10] processing. As ICMS elicits meaningful and repeatable percepts, it may also be used to restore sensation for patients who have lost it [8, 9, 11-17]. Sensitivity to ICMS has been studied by measuring the detectability and discriminability of different regimes of electrical stimulation applied to different cortical regions [1, 8, 12, 18-24]. These previous studies provide important insights on how changing different parameters affects the resulting perceptual experience. However, quantitative predictions about the detectability or discriminability cannot be made based on these previous studies, given how sparsely the parameter space is sampled. To fill this gap, we sought to develop a model that predicts the sensitivity to ICMS whose parameters span the range that has been deemed safe [25]. To this end, we developed a simple simulation of ICMS-evoked activation in a neuronal population and then used ideal observer analysis to predict behavioral sensitivity from the simulated population response. The model was developed based on behavioral data we had previously collected that characterize the detectability and discriminability of ICMS applied to the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) of macaques and spanning a wide range of stimulation parameters [23]. We find that the simple model can accurately predict sensitivity to ICMS across all conditions tested.

Methods

Behavioral methods

The methods are described in detail in a previous paper [23] and are only summarized here.

Animals and implants

Procedures were approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Each of two male Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta, 6 years of age, around 10 kg in weight) was implanted with a Utah electrode array (UEA; Blackrock Microsystems) in the hand representation of area 1 of the right hemisphere. After about 2 years of data collection, the array of one of the animals failed so another array was implanted in area 1 of its left hemisphere. Each UEA consists of 96 electrodes with 1.5-mm-long shanks, spaced 400 μm apart, and spanning a 4 × 4-mm area. The electrode tips are coated with a sputtered Iridium Oxide film using a standard process [26, 27]. The electrode shaft is insulated with parylene-C along its length, with the exception of the tip, which has a targeted exposure length of 50-μm. Electrode impedances were measured to be between 10 and 80 kΩ prior to implantation. We mapped the receptive field of each electrode by identifying which areas of skin evoked multiunit activity (monitored through speakers). Stimulation pulses were delivered using a 96-channel constant-current neurostimulator (CereStim R96, Blackrock Microsystems).

Behavioral tasks

Two animals were trained to perform two variants of a two-alternative forced choice task (2AFC): detection and discrimination. Animals were seated at the experimental table facing a monitor, which signaled the trial progression. Each trial comprised two successive stimulus intervals, each 1 sec and separated by a 1-sec inter-stimulus interval. The animals responded by making saccadic eye movements to a left or right target presented on the visual monitor and correct responses were rewarded with water or juice. The animals were first trained with mechanical stimuli, consisting of mechanical indentation of the skin with varying depth (from 0 to 2000 μm), until performance stabilized. Their task was to report which stimulus interval contained the only mechanical indentation (detection) or the mechanical indentation of greater depth (discrimination). The animals then performed the same detection and discrimination tasks based on ICMS of S1 (see below for a detailed description of each behavioral task). Unless otherwise specified, ICMS consisted of a train of symmetric biphasic pulses with cathodal phase leading and an interphase interval of 53 μs. Performance was very similar across animals, as previously documented [8, 23], so we combined results from the two animals for the purposes of the present modeling effort.

Detection

On each trial, ICMS was delivered in one of two consecutive stimulus intervals and the animal's task was to indicate which stimulus interval contained the stimulus. In different experimental blocks, we investigated the effects of pulse width (from 50 to 400 μs), pulse train frequency (from 50 to 1000 Hz), and pulse train duration (from 2 to 1000 ms) on the animals’ ability to detect stimuli varying in amplitude. We also studied the interaction between frequency and duration by varying these two parameters while keeping the pulse amplitude fixed at 40-μA (chosen because it was near threshold) as well as the interaction between pulse width and frequency using the range of amplitudes. Each manipulation was repeated with multiple electrodes to gauge the generality of our results.

Amplitude discrimination

On each trial, two ICMS pulse trains were presented sequentially and the animals’ task was to indicate which of the two was stronger. One of the two stimuli was a standard stimulus, with amplitude of 70 μA (approximately half way between threshold and maximum amplitude), and the other was a comparison stimulus whose amplitude varied from trial to trial. We varied ICMS frequency (from 50 to 500 Hz) or pulse train duration (from 50 to 1000 ms). In those conditions, the frequency or duration was the same for both intervals but varied randomly from trial to trial.

Computational model

Model overview

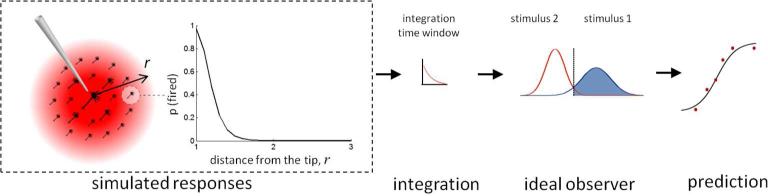

The proposed computational model consists of two parts: (1) simulating the responses evoked in populations of neurons by ICMS pulse trains and (2) predicting behavioral responses based on these simulated neuronal responses (Figure 1). To simulate the responses of an individual neuron, we compute its probability of firing in response to each ICMS pulse [28-30], taking into consideration both the properties of the stimulation pulse and the neuron's recent spiking history (the latter to incorporate absolute and relative refractoriness). The firing probabilities are then summed over all ICMS pulses to determine that neuron's response. To simulate the population response, the current waveform is described as decaying in amplitude as it spreads away from the stimulation site. The behavioral response is determined by comparing the simulated neuronal response to the ICMS pulse train delivered in each stimulus interval using ideal observer analysis. The model comprises 11 free parameters, which are optimized to fit the behavioral data [23]. The model thus provides a succinct description of a complex behavioral data set using a simple description of the process that culminates in the measured behavior.

Figure 1.

The model generates a population response from simulated neurons placed at different distances from the tip of electrode. The firing probability for each pulse decreases as the distance increases. The simulated responses are integrated using a time window to calculate a distribution of the population response for each stimulus and then predict detection and discrimination performance.

Neuronal simulation

Fluctuations of the membrane potentials at the nodes of Ranvier of myelinated fibers have been shown to be approximately normally distributed [31]. Accordingly, the threshold current, Ith, which bridges the gap between resting membrane potential and threshold (assuming a constant threshold, cf. ref [28]), is also distributed normally, so the firing probability of a neuron can be modeled as Bernoulli random variable, p, driven by current Ic as follows:

| (Eq. 1) |

and the probability that a spike will be evoked by a given ICMS pulse is given by [30]:

| (Eq. 2) |

where Ic is the ICMS current, G is a gain parameter, and Ith50 is the mean threshold current, that is, the current that causes the neuron to fire with a probability of 50%. Because the standard deviation of the membrane potential increases approximately linearly with its mean, the standard deviation of the threshold current is also a linear function of its mean σ = sIth50 [28, 31, 32], where s is the “relative spread.” After each spike, the threshold current Ith jumps up then decays exponentially along a time course that tracks absolute and relative refractoriness [28]:

| (Eq. 3) |

where tabs represents an absolute refractory period (fixed at 1 ms) during which the firing probability equals zero (see Eqs 2,3); γ and τref reflect the spike-triggered conductance change and its decay time constant, respectively. The effect of pulse width PW on threshold I0 is described according to the following empirical relationship [30, 33]:

| (Eq. 4) |

where I0,PW=∞ is the threshold current for long pulses, equivalent to the rheobase current, and C is the chronaxie, which is the time required for ICMS that is double the strength of the rheobase current to stimulate a neuron and is necessary to incorporate the effects of pulse width on sensitivity.

Using Equations 2-4, then, we computed the firing probability of each simulated neuron in response to a train of ICMS pulses. After each spike, the membrane potential returned to its resting state, the threshold increased [34, 35] then decayed back to its resting level after the absolute refractory period (see Eq. 3), resulting in a decrease in firing probability during the refractory period (Eq. 2). After computing the firing probability of the first pulse using Eq. 2 (with Ith50 = I0), the model recursively calculates the firing probability for the rest of pulses.

The number of spikes evoked in each neuron by a pulse train is given by the sum of firing probabilities across pulses. We then calculate the number of spikes generated by neurons across the volume of simulated tissue, over which the ICMS current decays at a rate of 1 / r2, where r is distance from the electrode tip. We used 21 neurons from nearest (r = 1) to farthest (r = 3) with an increment Δr = 0.1, having established that the results were relatively insensitive to the number (or density) of simulated neurons. The firing probability and corresponding spike counts decrease as distance increases and converges to zero (Figure 1).

Because neurons in the stimulated volume fired independently (that is, were not synaptically connected) in this simplified model, spikes were spatially and temporally integrated to calculate the effective number of spikes, Rp evoked in the neuronal population (Eq. 5). To incorporate the fact that neuronal signals are not integrated indefinitely, but rather over tens or hundreds of milliseconds [36, 37], in making a perceptual decision, we used an exponentially decaying time window, wn, whose time course was a parameter.

| (Eq. 5) |

where p(n,r) denotes the firing probability of a neuron located at distance r by the nth pulse, N is the number of ICMS pulses, and wn is an exponentially decaying function with time constant τi. The term 4πr2 computes from the neuronal responses evoked along radius r the responses evoked over a volume consisting of a series of 21 concentric spheres of radius r.

Given that the spike count follows the binomial distribution, the variance of the population response is given by:

| (Eq. 6) |

In summary, there are 11 free parameters: I0,PW=∞ (rheobase current), C (Chronaxie), γ (conductance change), τref (time constant of refractoriness), s (proportionality constant to relate variability of the input current to its amplitude), τi (time constant of the integration time window) (Eq. 5), and 5 gain parameters (3 for detection and 2 for discrimination (G in Eq. 2 and Table 1). The gain parameter was fit to each protocol separately to account for observed differences in sensitivity across conditions, likely caused by sensory adaptation and learning (see below). Note, however, that the gain parameter changes the overall sensitivity to ICMS but does not affect the relative sensitivity to different ICMS pulse trains. Parameters were optimized to minimize the mean squared error (RMSE) between actual and predicted performance (see below) for the detection and discrimination tasks. For this, we used a combination of Matlab function fmincon with multiple initial points and simulated annealing [38].

Table 1.

(A) Fitted values of the IF parameters, used for all protocols. (B) Fitted values of the gain parameter (G) for each protocol (see Eqs. 2-5).

| (A) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I0,PW=∞ (μA) | C (ms) | s | τref (ms) | γ | τi (ms) | |

| Estimated | 3.71 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 112 | 2.32 | 40.0 |

| (B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manipulation | G | G (validation) | |

| Detection | Pulse phase duration | 0.29 | 0.17 |

| Pulse train frequency | 0.20 | 0.16 | |

| Pulse train duration × frequency | 0.60 | ||

| Pulse train duration | 0.29 | ||

| Discrimination | Pulse train frequency | 0.11 | |

| Pulse train duration | 0.16 | ||

| Reference amplitude | 0.10 | ||

Ideal observer analysis

From Eqs. 5 and 6, the population response evoked by stimulus 1 on any given trial is given by:

| (Eq. 7) |

where np1 is the random deviation (i.e, noise) of the actual response from the mean response. The ideal observer analysis assumes that stimulus 1 (the comparison stimulus) will be perceived as more intense than stimulus 2 (the standard stimulus) if rp1 > rp2, the probability of which is given by:

| (Eq. 8) |

where P stands for the cumulative distribution function of the random variable indicated in the subscript. Since the population response is the sum of independent responses of individual neurons, it is normally distributed, according to the central limit theorem. The response variance was computed from Eq. 6 so Eq. 8 can be rewritten as:

| (Eq. 9) |

where Φ is the cumulative Gaussian function with unit variance. In signal detection, the argument of Φ is the discriminability, [39]. On detection trials, the responses on a blank interval, Rp2, was equal to zero.

Results and discussion

Behavioral data

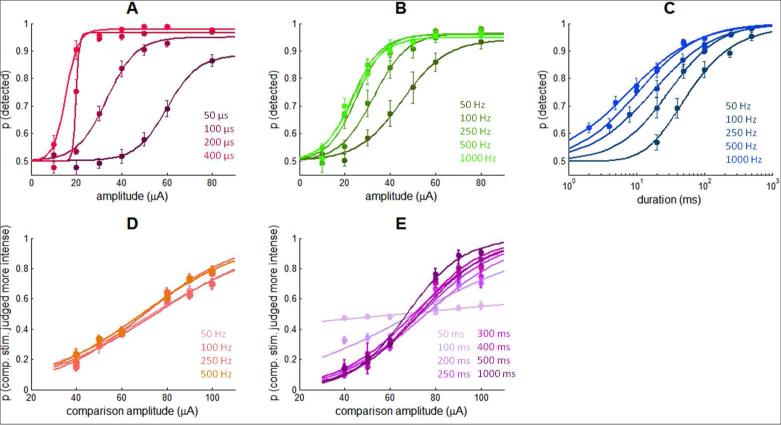

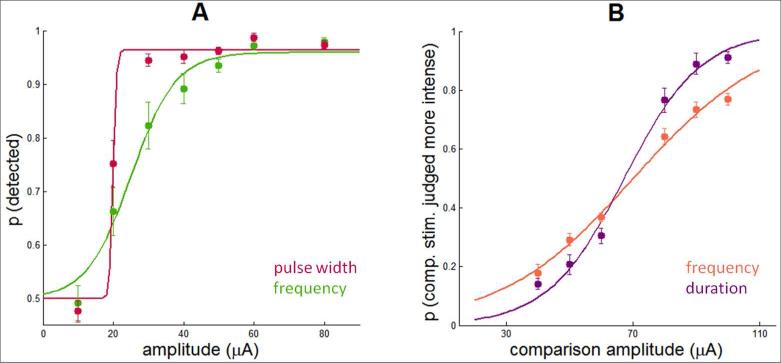

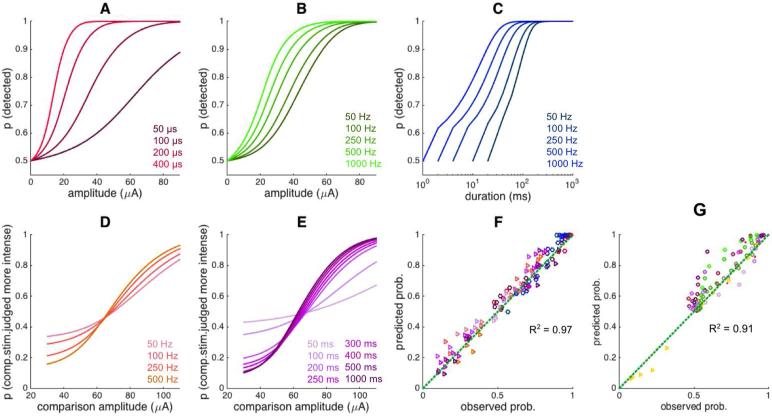

As described previously in more detail [23], detection performance improved as ICMS amplitude and duration increased, regardless of what other parameters were manipulated (Figure 2A-C). However, the psychometric functions and resulting detection thresholds were also dependent on the other parameters [40]. In brief, thresholds decreased with increases in pulse width and pulse frequency, both effects tending to level off (~200 μs for pulse width and ~250 Hz for frequency). As might be expected, discrimination performance improved as the difference in amplitude between the two stimuli increased (Figure 2D,E). Unlike its detection counterpart, however, discrimination performance was relatively insensitive to ICMS frequency; discrimination performance improved with increased stimulus duration up to about 200 ms and leveled off, a phenomenon that is also observed with the discrimination of mechanical stimuli applied to the skin [41]. Finally, performance varied across experiments for the same set of electrodes and identical stimulation regimes (Figure 3). For example, sensitivity was higher for experimental blocks where pulse width (detection) or stimulus duration (discrimination) was manipulated than for blocks where frequency was manipulated. The ICMS parameters are almost the same except for a small difference in frequency (250 Hz vs. 300 Hz), which is unlikely to underlie the observed difference. To account for this variability, the model included a gain parameter that was allowed to vary across protocols (Eq.2, Table 1B), with higher gain denoting higher sensitivity.

Figure 2.

Behavioral data. A| Detection, pulse width manipulation (300 Hz, 1s duration)(8 electrodes, 9666 trials). B| Detection, frequency manipulation (200 μs pulse width, 1s duration)(8 electrodes, 14,320 trials). C| Detection, frequency and duration manipulation (40 μA, 200 μs pulse width)(8 electrodes, 16,400 trials). D| Discrimination, frequency manipulation (200 μs pulse width, 1s duration, standard amplitude is 70 μA)(3 electrodes, 4,449 trials). E| Discrimination, duration manipulation (300 Hz, 200 μs pulse width, standard amplitude is 70 μA)(3 electrodes, 6,584 trials).

Figure 3.

Comparison of psychometric functions to ICMS with almost identical parameters but selected from two different experiments (a subset of those shown in Figure 2Error! Reference source not found.): A| Detection experiments, frequency and pulse width manipulations. For both, PW = 200 μs and stim. dur. = 1 sec; PF is 250 Hz for the PF manipulation and 300 Hz for the PW manipulation. B| Discrimination experiments, frequency and duration manipulations. For both, PW = 200 μs and stim. dur. = 1 sec; PF is 250 Hz for the PF manipulation and 300 Hz for the duration manipulation. The difference in performance across these paired conditions cannot be accounted for based on the small difference in frequency and reflects differences in sensitivity across these different protocols. These differences may be due to different states of sensory adaptation or different levels of training (the two were confounded in these data sets).

Neuronal simulation

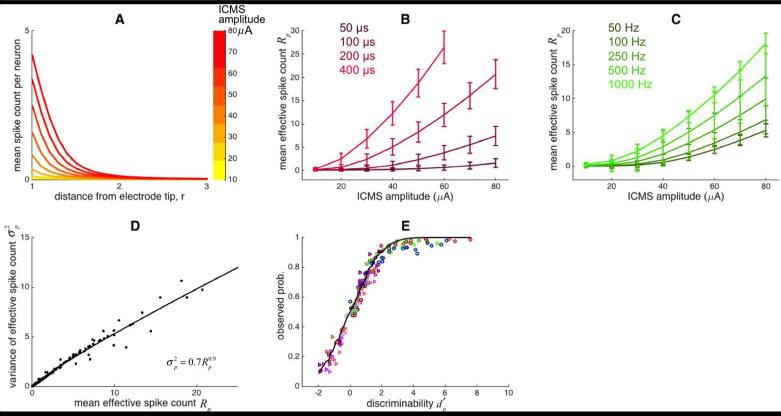

The goal was to develop a model that predicted performance on the ICMS detection and discrimination tasks. The model comprised two components (Figure 1): The first was a simulation of the neuronal activity evoked by each ICMS pulse train; the second was an ideal observer analysis that simulated the perceptual decision of which of two intervals was selected on a given detection or discrimination trial. In brief, each simulated neuron was subjected to the ICMS waveform, with amplitude decaying as an inverse function of the square of the neuron's distance from the electrode tip [42]. Thus, simulated neurons that were farther away from the electrode tip generated fewer spikes (Figure 4A). As expected, larger ICMS currents induced more spikes from individual neurons and from the neuronal population. Specifically, the simulated response increased with both pulse width (Figure 4B) and pulse frequency (Figure 4C). Of course, the population spike count increased with ICMS durations, but the effect of stimulus duration on detection or discrimination performance was limited by the integration time window [36, 37]. The variance of the population response was well approximated using a power function (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

A| Mean firing rate in a single simulated neuron as a function of distance from the electrode tip. The parameters of ICMS for this simulation: amplitude (from 10 to 80 μA), pulse phase duration (200 μs), frequency (300 Hz), pulse train duration (1s). Due to relative refractoriness, the maximum number of spikes was limited - that is, not every ICMS pulse evoked a spike. B| Mean population response as a function of ICMS amplitude with varying pulse width. C| Mean population response as a function of ICMS amplitude with varying frequency. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the population response. D| Relationship between the mean and the variance of the population response modeled as a power function. E| The discriminability was calculated from simulated neuronal responses and used to predict detection and discrimination performance using ideal observer analysis. Circles and triangles indicate detection trials and discrimination performance, respectively. Different colors denote different experimental conditions (see Figures 3 and 5). The black line shows the predicted probability (see Eq. 9).

Predicting behavioral responses from simulated neuronal responses

As described above, we simulated the population response to each ICMS pulse train then computed the behavioral response using ideal observer analysis (Eq. 10, Figure 4E). The parameters of the model were fit so that the resulting predictions matched the large behavioral data set, which consisted of 159 different ICMS combinations, 87 from detection and 72 from discrimination. The parameters of the neuronal model (Table 1A) were identical across protocols except for the gain parameter (Table 1B), which was allowed to vary across protocols to account for the varying sensitivity to the same (or similar) ICMS pulse trains (Figure 3). Once model parameters were optimized to fit the behavioral data, we constructed psychometric functions for the pulse width and pulse frequency manipulations in the detection experiments by simulating the population response for ICMS trains whose amplitude spanned the range from 10 to 90 μA in 1 μA steps and computing the resulting detectability (Figure 5A,B). For the duration/frequency manipulation (Figure 5C), the number of ICMS pulses was increased in increments of 1. For the pulse frequency and duration manipulations in the discrimination experiments, we simulated the responses of comparison stimuli ranging in amplitude from 20 μA to 100 μA and compared these to each of the fixed standards (Figure 5D,E).

Figure 5.

Model prediction: Predicted detection performance with manipulations of A| pulse width, B| frequency, C| duration and frequency; predicted discrimination performance with manipulations of D| pulse frequency and E| pulse train duration. F| Model fit. The model somewhat underestimates the effect of frequency on detectability but otherwise captures the behavioral data very accurately, accounting for 96% of the variance. Circles and triangles indicate detection and discrimination performance, respectively. Color codes are matched with ones shown in Figure 3E and in panels A-E; circles denote detection, triangles denote discrimination. G | Model prediction for the validation data, which were not used to fit the model parameters. Discrimination: 16 electrodes, 20,052 trials; detection – pulse width: 5 electrodes, 18,460 trials; detection – frequency: 4 electrodes, 33,281 trials; detection – duration: 4 electrodes, 13,337 trials. The same color and shape codes are used as in previous panels.

This simple model could predict both detection and discrimination performance with high accuracy (R2 = 0.97, RMSE = 0.052, Figure 5F). That is, the dependence of the simulated population response on stimulation parameters mirrored the dependence of the behavioral sensitivity to these same parameters. In other words, the model can accurately predict the degree to which a given ICMS pulse is detectable or the degree to which a pair of ICMS pulses are discriminable across all conditions tested. The model is able to predict behavior across a wide range of conditions even though it does not take into consideration neuronal morphology [43, 44], the biophysics of the stimulation and of neuronal activation [45], and the active spread of neuronal activity through synaptic connections [43, 44, 46, 47].

Model validation

We validated the model by testing it on behavioral data sets that were not used to fit its parameters [23]. One of the main differences between model-fitting and validation datasets was that the polarity of the pulses was reversed in the validation set (from cathodal to anodal phase leading). One validation dataset consisted of behavioral performance on a detection task, with varying pulse width, pulse train frequency, or pulse train duration. The other consisted of performance on a discrimination task with two different reference amplitudes (at 30 μA and 100 μA). These datasets consisted of 100 different conditions, 90 from the detection experiments and 10 from the discrimination experiments. All the model parameters were fixed, except for the gain parameter, which was fit to individual behavioral sets to compensate for differences in overall sensitivity, especially necessary given the well-documented phenomenon that anodal phase leading pulses lead to lower sensitivity [21, 48, 49]. The model accounted for 91% in the variance of the validation set (Figure 5G)(R2 = 0.91, 0.89, 0.79 for the three detection protocols, respectively, and 0.99 for the discrimination protocol). Thus, the model generalizes to a data set that was not used to obtain its parameters (except for the G, which was refit).

We also wished to assess whether a simpler possible model, one in which detection and discrimination predictions are based solely on charge delivery, could predict behavioral performance. To this end, we computed the amount of charge delivered during each stimulus and fit a logistic function to detection performance as a function of charge delivered and to discrimination performance as a function of difference in charge delivered. This model comprised two free parameters for each experiment condition for a total of 10 parameters. Model performance accurately predicted the effects of phase duration on detection and those of pulse train duration on discrimination but fared very poorly in all other conditions (see Table S1). Thus, the present model outperforms a marginally simpler model, suggesting that its (relatively low) level of complexity is warranted.

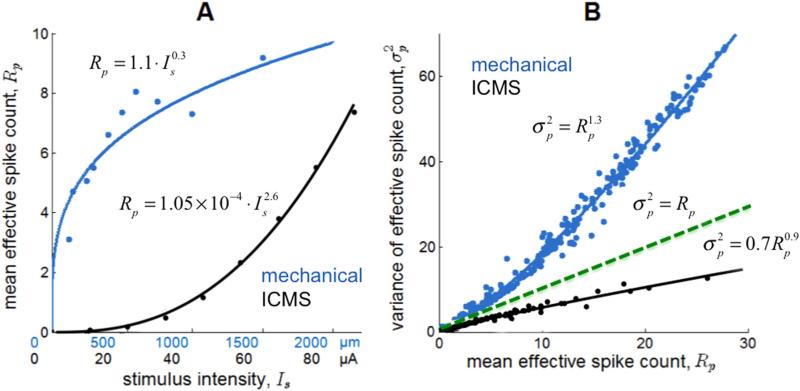

Comparison of simulated ICMS-evoked responses to measured mechanically evoked responses

Having established that the computational model can accurately predict behavioral performance, we compared the simulated responses to ICMS with measured neuronal responses to mechanical stimulation. To this end, we used neurophysiological recordings from S1 obtained while the animals performed detection and discrimination tasks based on mechanical stimulation of the skin that were analogous to those described above for ICMS. From these data, we calculated the effective spike count using the same integration time window used for the simulated responses. For the measured responses to mechanical stimulation, we found that the rate-intensity was a negatively accelerating function of stimulus amplitude and could be well approximated using a power function with exponent less than 1 (α ≈ 0.3) (Figure 6A); furthermore, variance increased slightly supra-linearly with firing rate (β ≈ 1.3) (Figure 6B). In contrast, simulated neuronal responses to ICMS exhibited the opposite pattern: The rate-intensity function was accelerating (α ≈ 2.6) (Figure 6A) and the variance-rate function decelerating (β ≈ 0.9.) (Figure 6B). The shallow variance rate function reflects the highly synchronized population responses to ICMS [50]. According to this model, which accurately captures the behavioral performance of the animal, the neuronal activation evoked by ICMS has different properties than does its counterpart evoked by mechanical stimulation of the skin. These differences in rate-intensity and variance-rate functions across modes of activation might account for the fact that mechanical discrimination follows Weber's law whereas electrical stimulation does not [23].

Figure 6.

Comparison of effective spike count resulting from mechanical stimulation (measured) and ICMS (simulated). A| Firing rates as a function of stimulus intensity, mechanical indentation (blue, recorded) and ICMS amplitude (black, modeled). B| Relationship between the mean and the variance of the mean effective spike count for mechanical stimulation (blue, recorded) and ICMS (black, modeled).

Model parameters

The optimized parameters for the neuronal model are comparable to equivalent quantities measured in cortical neurons (Table 1A). In visual cortex, measured rheobase currents, I0,PW=∞, span a wide range, from 1 to 500 μA [51] as do chronaxies, C, from 0.03 to 31 ms, depending on the cell type [48, 52]. These two parameters are required to capture the dependence of sensitivity on pulse width (Figure 2A, 5A). The fitted relative spread, s (0.22), is larger than but comparable to that measured in auditory neurons of cats (which ranges from 0.05 to 0.4)[29, 53]. The two parameters modulating relative refractoriness, γ and τref (2.32 and 112 ms respectively), are in the same order of magnitude as those used in previous models (γ = 0.97 in refs. [28-30] and τref = 100 in ref. [54]). These two parameters were optimized to capture the saturation of sensitivity at high frequencies shown in Figure 2B,C,D, 5B,C,D) Lastly, the time constant of the integrating window, τi (40 ms), is comparable to that derived in previous studies (5-8 ms in [37], 12-22 ms in [36]) and this parameter is required to capture the effect of the pulse train duration (Figure 2C, 2E, 5C, 5E).

We also tested how sensitive the predictions of the model were to the value of each of its parameters (Figure S1). We found that model performance was highly sensitive to the two time constant parameters, τref and τi, but much less sensitive to parameters such as rheobase current, I0,PW=∞ and spike-triggered conductance change, γ.

Comparison with a previous model

In a previous model [24], the performance of rodents on an ICMS discrimination task was predicted based on a leaky integrator of delivered charge. A logistic function (with 4 free parameters) was fit to the data relating discrimination performance to integrated charge, so variability in the underlying percepts was not explicitly represented in the model. The model could predict the animals’ ability to distinguish ICMS pulse trains varying in amplitude, frequency, or duration. Importantly, however, a different logistic function was fit to each condition. Unlike the present model, then, a single set of parameters could not account for discrimination across all conditions. Thus, while the study concluded that changes in ICMS amplitude, frequency, and duration all have consequences on perceived magnitude, the relative contributions of these to discriminability could not be inferred from the model. The present model fills that gap by accounting for the effects of all stimulation parameters with a single set of parameters (in addition to the variable gain). It is important to note that the gain parameter would be unnecessary if all stimulation conditions had been interleaved within each experimental block.

Model limitations

First, simulated neurons are excited by current that is passively diffusing away from the electrode tip, which is at odds with the observation that ICMS excites primarily axons rather than cell bodies [55]. Second, neurons in the model are not interconnected even though circuit-level dynamics may play a role in shaping the detectability and discriminability of ICMS pulse trains. Third, the gain parameter needs to be adjusted to the animal's sensitivity. In practice, this parameter could be estimated based on a few threshold measurements and the resulting model could then be used to predict a much larger data set. Note also that, while the gain parameter determines the overall sensitivity to ICMS, it does not affect the relative sensitivity to different ICMS trains. Fourth, the model does not take into account the neuronal adaptation – the progressive desensitization to ICMS over the course of an experimental block – caused by prolonged stimulation. Indeed, adaptation may have in part underlied the requirement for different gain parameters for different conditions, each with different overall levels of stimulation (the other cause for different gains being learning).

Conclusions

Despite its simplicity, the proposed model accurately captures detection and discrimination behavior across the behaviorally relevant range of stimulation conditions. The model can thus be an invaluable tool to develop ICMS regimes with known psychometric properties without time-consuming preliminary psychophysical experiments. Furthermore, results from the neuronal simulation suggest a reason why ICMS amplitude discrimination violates Weber's law.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Warren Grill and Hannes Saal for their helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript. This work was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency under contract N66001-10-C-4056 and NIH grant R01 NS 095251.

REFERENCES

- 1.Histed MH, Ni AM, Maunsell JH. Insights into cortical mechanisms of behavior from microstimulation experiments. Prog Neurobiol. 2013 Apr;103:115–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt E, Bak M, Hambrecht F, Kufta C, O'rourke D, Vallabhanath P. Feasibility of a visual prosthesis for the blind based on intracortical micro stimulation of the visual cortex. Brain. 1996;119:507–522. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salzman CD, Britten KH, Newsome WT. Cortical microstimulation influences perceptual judgements of motion direction. Nature. 1990;346:174–177. doi: 10.1038/346174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphey DK, Maunsell JH. Behavioral detection of electrical microstimulation in different cortical visual areas. Curr Biol. 2007 May 15;17:862–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otto KJ, Rousche PJ, Kipke DR. Microstimulation in auditory cortex provides a substrate for detailed behaviors. Hearing Res. 2005;210:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deliano M, Scheich H, Ohl FW. Auditory cortical activity after intracortical microstimulation and its role for sensory processing and learning. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15898–15909. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1949-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romo R, Salinas E. Flutter discrimination: neural codes, perception, memory and decision making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:203–218. doi: 10.1038/nrn1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabot GA, Dammann JF, Berg JA, Tenore FV, Boback JL, Vogelstein RJ, Bensmaia SJ. Restoring the sense of touch with a prosthetic hand through a brain interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Nov 5;110:18279–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221113110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.London BM, Jordan LR, Jackson CR, Miller LE. Electrical stimulation of the proprioceptive cortex (area 3a) used to instruct a behaving monkey. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2008;16:32–36. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2007.907544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkatraman S, Carmena JM. Active sensing of target location encoded by cortical microstimulation. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2011 Jun;19:317–24. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2011.2117441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bensmaia SJ, Miller LE. Restoring sensorimotor function through intracortical interfaces: progress and looming challenges. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014 May;15:313–25. doi: 10.1038/nrn3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg JA, Dammann JF, 3rd, Tenore FV, Tabot GA, Boback JL, Manfredi LR, Peterson ML, Katyal KD, Johannes MS, Makhlin A, Wilcox R, Franklin RK, Vogelstein RJ, Hatsopoulos NG, Bensmaia SJ. Behavioral demonstration of a somatosensory neuroprosthesis. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2013 May;21:500–7. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2013.2244616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otto KJ, Rousche PJ, Kipke DR. Microstimulation in auditory cortex provides a substrate for detailed behaviors. Hear Res. 2005 Dec;210:112–7. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otto KJ, Rousche PJ, Kipke DR. Cortical microstimulation in auditory cortex of rat elicits best-frequency dependent behaviors. J Neural Eng. 2005 Jun;2:42–51. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/2/2/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis TS, Parker RA, House PA, Bagley E, Wendelken S, Normann RA, Greger B. Spatial and temporal characteristics of V1 microstimulation during chronic implantation of a microelectrode array in a behaving macaque. J Neural Eng. 2012 Dec;9:065003. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/9/6/065003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Normann RA, Greger B, House P, Romero SF, Pelayo F, Fernandez E. Toward the development of a cortically based visual neuroprosthesis. J Neural Eng. 2009 Jun;6:035001. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/6/3/035001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobelle WH. Artificial vision for the blind by connecting a television camera to the visual cortex. ASAIO J. 2000 Jan-Feb;46:3–9. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romo R, Hernandez A, Zainos A, Brody CD, Lemus L. Sensing without touching: psychophysical performance based on cortical microstimulation. Neuron. 2000 Apr;26:273–8. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romo R, Hernandez A, Zainos A, Salinas E. Somatosensory discrimination based on cortical microstimulation. Nature. 1998 Mar 26;392:387–90. doi: 10.1038/32891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koivuniemi AS, Otto KJ. The depth, waveform and pulse rate for electrical microstimulation of the auditory cortex. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 20122012:2489–92. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6346469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koivuniemi AS, Otto KJ. Asymmetric versus symmetric pulses for cortical microstimulation. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2011 Oct;19:468–76. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2011.2166563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S, Callier T, Tabot GA, Tenore FV, Bensmaia SJ. Sensitivity to microstimulation of somatosensory cortex distributed over multiple electrodes. Front Syst Neurosci. 2015;9:47. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S, Callier T, Tabot GA, Gaunt RA, Tenore FV, Bensmaia SJ. Behavioral assessment of sensitivity to intracortical microstimulation of primate somatosensory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Dec 8;112:15202–15207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509265112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fridman GY, Blair HT, Blaisdell AP, Judy JW. Perceived intensity of somatosensory cortical electrical stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 2010 Jun;203:499–515. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2254-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajan AT, Boback JL, Dammann JF, III, Tenore FV, Wester BA, Otto KL, Gaunt RA, Bensmaia SJ. the effect of chronic intracortical microstimulation on neural tissue and fine motor behavior. Journal of neural engineering. 2015;12:066018. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/12/6/066018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negi S, Bhandari R, Rieth L, Solzbacher F. In vitro comparison of sputtered iridium oxide and platinum-coated neural implantable microelectrode arrays. Biomedical Materials. 2010 Feb;5:15007. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/5/1/015007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negi S, Bhandari R, Rieth L, Van Wagenen R, Solzbacher F. Neural electrode degradation from continuous electrical stimulation: comparison of sputtered and activated iridium oxide. J Neurosci Methods. 2010 Jan 30;186:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruce IC, Irlicht LS, White MW, O'Leary SJ, Dynes S, Javel E, Clark GM. A stochastic model of the electrically stimulated auditory nerve: pulse-train response. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1999;46:630–637. doi: 10.1109/10.764939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruce IC, White MW, Irlicht LS, O'Leary SJ, Dynes S, Javel E, Clark GM. A stochastic model of the electrically stimulated auditory nerve: single-pulse response. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1999 Jun;46:617–29. doi: 10.1109/10.764938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu Y, Collins LM. Predicting the threshold of pulse-train electrical stimuli using a stochastic auditory nerve model: The effects of stimulus noise. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2004;51:590–603. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2004.824143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verveen AA, Derksen HE, Schick KL. Fluctuations in membrane potential of axons and the problem of coding. Nature. 1967 Nov 11;216:588–9. doi: 10.1038/216588a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verveen A, Derksen H. Fluctuations in membrane potential of axons and the problem of coding. Kybernetik. 1965;2:152–160. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tehovnik EJ. Electrical stimulation of neural tissue to evoke behavioral responses. J Neurosci Meth. 1996;65:1–17. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller MI, Mark KE. A statistical study of cochlear nerve discharge patterns in response to complex speech stimuli. J Acoust Soc Am. 1992;92:202–209. doi: 10.1121/1.404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irlicht L, Clark GM. Control strategies for neurons modeled by self - exciting point processes. J Acoust Soc Am. 1996;100:3237–3247. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Q, Webber RM, Stanley GB. Thalamic synchrony and the adaptive gating of information flow to cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2010 Dec;13:1534–41. doi: 10.1038/nn.2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stuttgen MC, Schwarz C. Integration of vibrotactile signals for whisker-related perception in rats is governed by short time constants: comparison of neurometric and psychometric detection performance. J Neurosci. 2010 Feb 10;30:2060–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3943-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Press WH, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP. Numerical recipes in C. Citeseer. 1996;2 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kontsevich LL, Chen CC, Tyler CW. Separating the effects of response nonlinearity and internal noise psychophysically. Vision Res. 2002 Jun;42:1771–84. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Semprini M, Bennicelli L, Vato A. A parametric study of intracortical microstimulation in behaving rats for the development of artificial sensory channels. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 20122012:799–802. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6346052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luna R, Hernandez A, Brody CD, Romo R. Neural codes for perceptual discrimination in primary somatosensory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2005 Sep;8:1210–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grill WM, Norman SE, Bellamkonda RV. Implanted neural interfaces: biochallenges and engineered solutions. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2009;11:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Overstreet CK, Klein JD, Tillery S. Computational modeling of direct neuronal recruitment during intracortical microstimulation in somatosensory cortex. J Neural Eng. 2013;10 doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/6/066016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Histed MH, Bonin V, Reid RC. Direct activation of sparse, distributed populations of cortical neurons by electrical microstimulation. Neuron. 2009 Aug 27;63:508–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McIntyre CC, Grill WM. Selective microstimulation of central nervous system neurons. Ann Biomed Eng. 2000 Mar;28:219–33. doi: 10.1114/1.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tolias AS, Sultan F, Augath M, Oeltermann A, Tehovnik EJ, Schiller PH, Logothetis NK. Mapping cortical activity elicited with electrical microstimulation using FMRI in the macaque. Neuron. 2005 Dec 22;48:901–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Logothetis NK, Augath M, Murayama Y, Rauch A, Sultan F, Goense J, Oeltermann A, Merkle H. The effects of electrical microstimulation on cortical signal propagation. Nat Neurosci. 2010 Oct;13:1283–91. doi: 10.1038/nn.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ranck JB., Jr. Which elements are excited in electrical stimulation of mammalian central nervous system: a review. Brain Res. 1975 Nov 21;98:417–40. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt EM, Bak MJ, Hambrecht FT, Kufta CV, O'Rourke DK, Vallabhanath P. Feasibility of a visual prosthesis for the blind based on intracortical microstimulation of the visual cortex. Brain. 1996 Apr;119(Pt 2):507–22. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dinse HR, Recanzone GH, Merzenich MM. Alterations in correlated activity parallel ICMS-induced representational plasticity. Neuroreport. 1993 Nov 18;5:173–6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199311180-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ronner SF, Lee BG. Excitation of visual cortex neurons by local intracortical microstimulation. Exp Neurol. 1983 Aug;81:376–95. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(83)90270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nowak LG, Bullier J. Axons, but not cell bodies, are activated by electrical stimulation in cortical gray matter. I. Evidence from chronaxie measurements. Exp Brain Res. 1998 Feb;118:477–88. doi: 10.1007/s002210050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Javel E, Tong Y, Shepherd R, Clark GM. Responses of cat auditory nerve fibers to biphasic electrical current pulses. Scientific publications. 1987;4(226):1987–1988. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dayan P, Abbott LF. Theoretical neuroscience. Vol. 806. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Histed MH, Bonin V, Reid RC. Direct Activation of Sparse, Distributed Populations of Cortical Neurons by Electrical Microstimulation. Neuron. 2009;63:508–522. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.