Abstract

Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) are becoming a more frequent life-support intervention. Gaining an understanding of risk factors for infection and management strategies is important for treating these patients.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies describing infections in continuous-flow LVADs. We evaluated incidence, risk factors, associated microorganisms, and outcomes by type of device and patient characteristics.

Our search identified 90 distinct studies that reported LVAD infections and outcomes. Younger age and higher body mass index were associated with higher rates of LVAD infections. Driveline infections were the most common infection reported and the easiest to treat with fewest long-term consequences. Bloodstream infections were not reported as often, but they were associated with stroke and mortality. Treatment strategies varied and did not show a consistent best approach.

LVAD infections are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in LVAD patients. Most research comes from secondary analyses of other LVAD studies. The lack of infection-oriented research leaves several areas understudied. In particular, bloodstream infections in this population merit further research. Providers need more research studies to make evidence-based decisions about the prevention and treatment of LVAD infections.

Keywords: heart-assist device, infection, meta-analysis

Introduction

Although the number of patients affected by heart failure has increased over the past 2 decades, the number of heart transplants has remained relatively constant at about 3,500 to 4,000 per year because of the shortage of donor organs. This shortage has increased the use of mechanical circulatory support devices for patients with advanced heart failure refractory to treatment, particularly, left ventricular assist devices (LVADs).1 The Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) reports 5,408 such devices implanted between January 2012 and the end of the first quarter of 2014. Of these, 42.9% were considered destination therapy for patients not listed for heart transplant.2

As more devices have been implanted, LVAD infections, which are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, have become an increasingly important problem. The definitive treatment, removing the device, is often not feasible, thus making LVAD infections a devastating complication for affected patients. One prospective study showed a 22% overall infection rate of LVADs and a one-year mortality 5.6 times greater in patients with infections.3 Besides mortality, LVAD infections are associated with increased risk of pump thrombosis, bleeding complications, longer hospital stay, need for LVAD exchange, and failure to transplant.4 As more patients have LVAD support for longer periods, developing effective prevention and treatment strategies will become even more crucial.

The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) defines an LVAD infection as an infection occurring in the presence of an LVAD that may or may not be attributable to the LVAD, but that may warrant special consideration if an LVAD is in place. This definition includes several types of infections besides those directly associated with the device, such as catheter-related bloodstream infection or bacteremia attributable to pneumonia or urinary tract infection. LVAD infections can be further classified: driveline-related with accompanying soft tissue, pump pocket, LVAD-associated bloodstream infection, and endocardial infection with direct evidence of vegetation or infection on the internal surface of the pump.5

Earlier systematic reviews of LVAD infections have examined prophylactic strategies,5,6 tools for diagnosis and management,5 risk factors, and the microbiology of infections. The purpose of this systematic review is to analyze published studies regarding the incidence and risk factors for LVAD infections and describe the impact of each on patient-level outcomes.

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Our protocol was registered with PROSPERO (Registration No. CRD2014014114). We identified studies that described either the microbiology of continuous-flow LVAD infections or outcomes of these infections (mortality, length of stay, or costs of care). We included the following epidemiologic and experimental study designs: controlled trials, quasi-experimental designs, before-and-after studies, prospective and retrospective studies, and cross-sectional studies. We excluded individual case reports; review articles; basic science papers; animal studies; case-control studies (as our outcomes of interest are epidemiologic); studies primarily describing outcomes of right ventricular assist devices, biventricular assist devices, pneumatic LVADs (as infection rates were significantly higher in these first-generation devices) ; and pneumatic total artificial hearts. For mixed-population studies, authors were contacted to determine if a subset of data for patients who received continuous-flow devices could be obtained. Finally, pediatric studies were also excluded, as the indications and use of LVADs in adult and pediatric populations are distinct.

When a study was reported as both a preliminary and final analysis, preliminary analyses were excluded. For studies in which there was substantial, secondary data analysis reported separately for new outcomes, the results were combined for reporting purposes to minimize duplication.

Outcomes of Interest

Infections were the primary outcomes of interest in this study. We abstracted data regarding type of infection; microorganisms isolated; attempted therapies; patient-level outcomes of relapse or reinfection, or both; treatment failures; length of stay; and mortality. Infections were defined from individual studies; these definitions were abstracted and compared.

Search Strategy

With the assistance of a professional medical librarian at our institution, we determined our strategy for the literature search. We did not apply any language restrictions and searched the electronic databases of Medline (PubMed), Web of Science, EMBASE, Ovid, and CINAHL. We attempted to ensure a complete search of the health-related grey literature through searches of pertinent conference proceedings and abstracts. We manually reviewed the included references for other potentially relevant records.

Study Quality Assessment

Studies were assessed for methodologic quality by using the risk-of-bias assessment tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews.7 This tool allows for subjective assessment of bias across six domains, including selection, performance, attrition, detection, and reporting. The data were summarized using Review Manager 5 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Nordic Cochrane Center).

Data Collection

Data were abstracted using a standard REDCap form (Research Electronic Data Capture, Vanderbilt University) (Supplement 1) by two independent reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Data were synthesized qualitatively by category, and, when sufficient data were available, quantitatively using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects method for meta-analysis and Cochrane Review Manager 5 software.

Results

Search Results

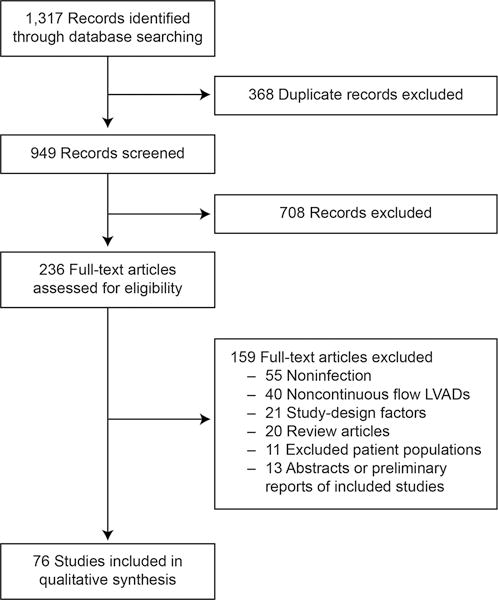

Ninety distinct studies were included in our final synthesis (Figure 1). Study characteristics, patient comorbidities, and infection data are summarized in Tables 1–3.

Figure 1.

PRISMA study selection flow diagram.

Table 1.

Study Characteristicsa

| First Author, Year |

Location | Device | Study Design |

No. of Patients |

Patient Age, Years |

% Men |

Race/ Ethnicity (%) |

Indication for LVAD (%) |

Duration of Support |

Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miller et al, 200746 | Multi-center | HeartMate II | Prospective, observational | 133 | 50.1 | 76.0 | White (69) African American (23) |

BTT (100) ICM (37) |

126 d, median | End-stage heart failure | Severe renal, pulmonary, or hepatic dysfunction; active, uncontrolled infection; mechanical aortic valve; aortic insufficiency; other support device (except IABP) |

| Schulman et al, 200724 | New York, USA | HeartMate II, DeBakey Micro-Med | Retrospective, case series | 27 | 55.1 (12.8) | 81.5 | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between October 2003 and April 2006 | NR |

| Struber et al, 200816 | Hanover, Germany | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 101 | 48 (13) | NR | NR | BTT (69.3) DT (30.7) |

NR | 12 European centers between March 2004 and January 2007 | NR |

| Morshuis et al, 200947 | Multi-center | DuraHeart | Prospective, observational | 33 | 55.5 (12.5) | 85.0 | NR | BTT (100.0) | 242 (243) d | Surgical contraindication to LVAD, high-risk cardiothoracic surgery within 30 days, aortic regurgitation, severe COPD, >1 week of ventilator support, active infection, end- stage renal or liver disease, primary RV dysfunction | NR |

| Lahpor et al, 201048 | Multi-center | HeartMate II | Registry review | 411 | 51.0 (14.0) | 81.0 | NR | NR | 236 (214) d | HeartMate II implanted in 1 of 64 European centers that contribute to the Thoratec data bank | Implantation <6 mo before study inception |

| Topkara et al, 201032 | Missouri, USA | HeartMate II, Ventr-Assist | Retrospective, case series | 81 | 51.8 (13.7) | 78.0 | White (77) African American (23) | DT (29.6) BTT (70.4) ICM (46.7) |

9.2 (9.2) mo | NR | NR |

| Wieselthaler et al, 201049 | Multi-center | Heart-Ware HVAD | Nonrandomized controlled trial | 23 | 48 (12.6) | 87.0 | NR | ICM (30.0) | 167 (143) d | Refractory end- stage heart failure with optimal medical therapy and inotropes. UNOS status 1A or 1B | Mechanical circulatory support (except IABP); cardiac transplant within 12 mo; mortality within 14 days; >72 h mechanical ventilation; PE within 2 weeks; mechanical valve; aortic regurgitation; active, uncontrolled infection; thrombocytopenia; uncontrolled coagulopathy; dialysis; liver failure |

| Bogaev et al, 201139 | Multi-center | HeartMate II | Secondary analysis of data from Heart-Mate II clinical trial and continuous access protocol | 465 | 51.8 (13.2) | 77.6 | NR | BTT (100.0) ICM (44.9) |

338.9 (335.9) d | At least 18 mo follow-up | HeartMate II clinical trial |

| Garbade et al, 201150 | Leipzig, Germany | HeartMate II or Heart-Ware | Retrospective, cohort | 49 | 53 (12) | 90.0 | NR | DT (16.0) BTT (84.0) |

138 (53) d | Implantation between 2006 and 2010 | NR |

| John et al, 201125 | Minnesota, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, cohort | 102 | 52.6 (12.8) | 74.5 | NR | BTT (100.0) | 327 (286) d | BTT | Exchange for device failure or destination therapy |

| John et al, 201151 | Multi-center | HeartMate II | Registry study | 1982 | NR | 77.2 | NR | BTT (100.0) | 9.7 mo | CF LVAD as BTT, data as reported to INTERMACS and from the original HeartMate II clinical trial | NR |

| Schaffer et al, 201115 | Maryland, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 86 | 49.7, mean | 70.9 | NR | DT (33.7) BTT (66.3) |

NR | Implantation between June 2000 and May 2009 | NR |

| Starling et al, 201125 | Multi-center | HeartMate II | Registry review | 169 | NR | 78.0 | White (74) African American (17) | BTT (100.0) | 306 (173) d | INTERMACS registry for BTT between April and August 2008 | NR |

| Aggarwal et al, 201220 | Illinois, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, cohort | 87 | 62 (12.8) | 86.0 | White (36) African American (49) |

NR ICM (57.4) | 923.5 (567.3) d | Consecutive patients, between 2005 and 2009 | Episode of transient bacteremia |

| Brewer et al, 201252 | Multi-center | HeartMate II | Retrospective, HeartMate II BTT and DT trials | 896 | 56.8 (14.1) | 76.1 | White (71.9) African American (20.2) |

NR | NR | Enrollment in HeartMate II clinical trials for BTT or DT | Exchange from HeartMate XVE to HeartMate II |

| Bomholt et al, 201153 | Copen-hagen, Denmark | HeartMate II | Retrospective, cohort | 31 | 46 (24–55) | 74.0 | White (100.0) | BTT (81.0) DT (19.0) ICM (26.0) |

317 (93–595) d | Consecutive patients | NR |

| Chamogeorgakis et al, 201227 | Ohio, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 135 | 54 (14) | 78.5 | NR | BTT (40.0) BTD (39.0) DT (21.0) |

NR | NR | NR |

| Donahey et al, 201231 | Georgia, USA | NR | Retrospective, case series | 57 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Eleuteri et al, 201254 | Pennsylvania, USA | HeartMate II, Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, cohort | 97 | 59 (10) | 81.0 | NR | BTT (33.0) BTC (21.6) DT (47.4) |

3359 (340) d | Implantation between 2006 and 2011 | NR |

| Fleissner et al, 201229 | Hanover, Germany | Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, cohort | 81 | 52 (16.1) | 82.7 | White (100.0) | ICM (45) NICM (55) |

258 (531) d | Implantation in 2008, 2009, or 2011 | NR |

| Goldstein et al, 201230 | Multi-center | NR | INTERMACS registry study | 2006 | NR, although younger age was a risk factor for percutaneous infection | NR, although older men were at increased risk for infection | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 6/2006 and 9/2010 | NR |

| Guerrero-Miranda et al, 201255 | New Jersey, USA | HeartMate II, DeBakey Micro-Med, Centri-Mag, DuraHeart, Ventr-Assist, Heart-Ware |

Retrospective, cohort | 120 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Hozayen et al, 201256 | Minnesota, USA | Heart-Ware, Ventr-Assist, Heart-Mate II | Retrospective, cohort | 63 | 57.5 (17.4) | 68.2 | NR | ICM (52.4) NICM (47.6) |

NR | NR | NR |

| Kamdar et al, 201557 | Multi-center | NR | Registry study | 2900 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | All patients entered in INTERMACS registry between 6/2006 and 3/2011 | NR |

| Krabatsch et al, 201258 | Berlin, Germany | Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case series | 142 | 55.1 (15.9) | 82.3 | NR | NR | 206 d, mean follow- up | Between 9/2009 and 10/2011 | Children, patients with congenital heart disease |

| Maiani et al, 201259 | Multisite, Italy | Jarvik 2000 | Registry study | 65 | 63.0 (8.0) | 89.2 | NR | DT (95) ICM (53) |

320 d, mean | Between 2006 and 2011 | NR |

| Mano et al, 201260 | Pittsburgh, USA | CF LVAD | Retrospective, cohort | 78 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 260 (265) d | Between 12/2006 and 6/2011 | NR |

| Menon et al, 201261 | Aachen, Germany | HeartMate II | Retrospective, cohort | 40 | 58.0 (11.0) | NR | NR | DT (22.5) BTT (62.5) BTC (15.0) ICM (72.5) |

NR | NYHA IIIB or IV heart failure, between 2008 and 2011 | NR |

| Park et al, 201262 | Multicenter trial | HeartMate II | Registry study | 281 | 63.3 (12.6) | 76.0 | NR | DT (100.0) ICM (24.0) |

1.7 y, mean | ≥2 y follow-up | Prior HeartMate XVE |

| Popov et al, 201263 | Harefield, United Kingdom | Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case series | 34 | 51.0 (10.0) | 85.3 | NR | NR | 261 (264) d | Implantation between 2007 and 2011 | NR |

| Schibilsky et al, 201264 | Tubingen, Germany | HeartMate II or Ventr-Assist | Retrospective, case series | 43 | 55.7 (13.3) | 83.7 | NR | DT (25.6) BTT (74.4) |

NR | Implantation between 2006 and 2010 | NR |

| Tarzia et al, 201265 | Multicenter, Italy | Jarvik 2000 | Registry review | 65 | 65, median | 89.2 | NR | ICM (53.0) | NR | Implantation between 2006 and 2011 | NR |

| Aldeiri et al, 201321 | Texas, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, cohort | 149 | 55.5 (13) | 75.8 | NR | ICM (59.0) | NR | Implantation between 2008 and 2012 | NR |

| Choudhary et al, 201328 | New York, USA | HeartMate II | Prospective, observational cohort | 171 | 54.0 (12.4) | 82.0 | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 11/2006 and 1/2013 | Death within 3 mo of device explant |

| Forest et al, 201323 | New York, USA | NR | Retrospective, cohort | 105 | 56 (14) | 82.0 | NR | DT (45.0) ICM (51.0) |

NR | Implantation between 2006 and 2012 | NR |

| Haj-Yahia et al, 200766 | Minnesota, USA | HeartMate II | Registry study | 115 | 62 [53–69] | 83.0 | NR | DT (64.0) BTT (36.0) |

NR | Survival to discharge, between 2008 and 2011 | NR |

| Lalonde et al, 201367 | Toronto, Canada | HeartMate II and Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case series | 46 | 50.1 (12.6) | 60.8 | NR | BTT (76.2) BTC (19.5) DT (4.3) ICM (26.1) |

NR | Implantation between 1/2006 and 4/2012 | NR |

| Nienaber et al, 201336 | Minnesota, USA | HeartMate II, Jarvik 2000, Ventr-Assist |

Retrospective, case series | 78 | 56.8 (14.9) | 79.0 | White (87.0) African American (7.0) |

DT (62.0) BTT (38.0) |

1.5 (1.0) y | Implantation between 2005 and 2011 | LVAD implanted elsewhere, RVAD |

| Slaughter et al, 201368 | Kentucky, USA | Heart-Ware HVAD | Prospective, observational | 332 | 52.8 (11.9) | 71.1 | White (68.7) African American (25.9) |

BTT (100.0) ICM (36.7) |

NR | UNOS status 1A or 1B | Other mechanical circulatory device (except IABP) |

| Smedira et al, 201317 | Ohio, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 92 | 53 (14) | 78.0 | NR | DT (22.0) BTT (78.0) |

NR | Implantation between 10/2004 and 1/2010 | NR |

| Stulak et al, 201369 | Minnesota, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 285 | 54, mean | 51.0 | NR | DT (41.0) BTT (39.0) ICM (53.0) |

NR | Primary VAD implantation | NR |

| Tong et al, 201326 | Ohio, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 254 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Between 2004 and 2012 | NR |

| Wu et al, 201370 | Berlin, Germany | Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case review | 141 | 51.6 (16.2) | 82.5 | NR | DT (28.4) BTT (71.6) ICM (44.7) |

NR | Between 8/2009 and 4/2011 | NR |

| Baronetto et al, 201440 | Turin, Italy | Heart-Ware HVAD | Prospective, observational cohort | 23 | 57.5 | 100.0 | White (100.0) | BTT (52.0) DT (48.0) |

7 mo | Implant with HeartWare HVAD between 4/2013 and 11/2013 | NR |

| Cagliostro et al, 201441 | New York, USA | HeartMate II (other devices unspecified) | Prospective, observational cohort | 253 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 2010 and 2013 | NR |

| Chan et al, 201471 | Singapore, Singapore | HeartMate II or Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, cohort | 40 | 41.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 5/2009 and 9/2013 | NR |

| Cogswell et al, 201472 | Minnesota, USA | HeartMate II or Heart-Ware HVAD | Matched cohort | 60 | 43 (14.6) | 80.0 | White (73.3) African American (16.6) Asian (1.6) |

BTT (95.0) DT (5.0) ICM (30.0) |

NR | Age >16 y; DSM, IV substance abuse (case arm) or documented lack thereof (matched cohort) | Death in hospital, contraindications to transplantation |

| Dean et al, 201473 | Multicenter | HeartMate II | Secondary analysis of Heart-Mate II destination therapy clinical trial | 401 | 60, median | NR | NR | BTT (50.0) DT (50.0) |

19 (7–46) mo | Inclusion in HeartMate II registry database | NR |

| Hieda et al, 201474 | Osaka, Japan | NR | Retrospective, case series | 16 | 37.5 (11.9) | 100.0 | Asian (100.0) | BTT (100.0) ICM (18.8) |

387 (228) d | BTT, between 2011 and 2013 | NR |

| Jennings et al, 201475 | Detroit, USA | NR | Retrospective, case series | 16 | 52, median | 69.0 | NR | DT (69.0) BTT (31.0) |

NR | Between 1/2008 and 8/2011, with systemic antimicrobial agent therapy for suppression of confirmed LVAD infection | Superficial percutaneous driveline infection |

| John et al, 201476 | Multicenter | Heart-Ware HVAD | Registry study | 332 | 52.7 (11.9) | 71.1 | NR | BTT (100.0) ICM (36.7) |

NR | Secondary analysis of ADVANCE BTT and CAP trial with ≥6 mo follow-up | NR |

| Jorde et al, 201477 | Multi-center | HeartMate II | Registry study | 380 | NR | 81.8 | White (74.5) African American (18.7) |

BTT (65.0) DT (35.0) ICM (60.0) |

NR | First 247 patients who had a HeartMate II implant after FDA device approval and 133 patients in the original HeartMate II clinical trial | NR |

| Kimura et al, 201433 | Tokyo, Japan | DuraHeart Evaheart | Retrospective, case series | 31 | 39.7 (11.7) | 84.0 | NR | BTT (100.0) ICM (12.9) |

NR | End-stage heart failure, BTT | HeartMate II device implantation |

| Koval et al, 201478 | Ohio, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 181 | 54 (13.8) | 80.0 | White (79.0) Other races unspecified |

DT (29) BTT (71) ICM (46) |

NR | Implantation between 10/2004 and 9/2011 | Previous LVAD |

| Kretlow et al, 201414 | Texas, USA | CF LVAD | Retrospective, case series | 26 | 51.3 (15.7) | 81.0 | NR | DT (7.7) BTT (92.3) |

NR | All patients treated by the senior author for LVAD infection | NR |

| Masood et al, 201437 | Michigan, USA | CF LVAD | Retrospective, case series | 328 | 56, median | 77.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Moazami et al, 201479 | Multicenter | DuraHeart | Prospective, observational study | 63 | 54 (11.3) | 84.0 | NR | BTT (100.0) ICM (49.0) |

NR | Advanced heart failure in patients listed for transplant at 1 of 40 investigator centers | NR |

| Nelson et al, 201480 | Pennsylvania, USA | HeartMate II and Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case series | 12 | 54.3 (19.3) | 75.0 | White (86.0) African American (14.0) | DT (42.0) BTT (58.0) ICM (58.0) DCM (17.0) NICM (17.0) Familial (8.0) |

NR | Patients who required plastic surgery for complex wound management, between 2008 and 2013 | NR |

| Nishi et al, 201481 | Osaka, Japan | Heart-Ware HVAD | Prospective, cohort | 9 | 33.5 (7.8) | 66.7 | NR | BTT (100.0) ICM (0) |

245 (162) d | Patients eligible for cardiac transplantation, taking maximal medical therapy | NR |

| Raymer et al, 201482 | Missouri, USA | HeartMate II Heart-Ware HVAD (35) | Retrospective case series | 316 | NR | 78.0 | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 6/2005 and 7/2013 | NR |

| Sabashnikov et al, 20148 | Harefield, United Kingdom | HeartMate II or Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, cohort | 139 | 44 (13.7) | NR | NR | BTT (100.0) ICM (11.0) DCM (83.0) PPM (1.0) HCM (5.0) |

514 (481) d | Implantation between 2007 and 2013 | NR |

| Singh et al, 201483 | Wisconsin, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 125 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 628 (231.1) d |

Implantation between 6/2008, and 10/2011 | NR |

| Subbotina et al, 201484 | Hamburg, Germany | Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case series | 38 | 57 (12) | NR | NR | ICM 31.6 | 10 (7) mo | Implantation between 1/2010 and 8/2013 | NR |

| Takeda et al, 201485 | New York, USA | HeartMate II, Ventr-Assist, Dura-Heart, DeBakey Micro-Med | Retrospective, case series | 140 | 54.7 (14.4) | 79.3 | ICM (36.4) | DT (17.9) BTT (82.1) |

NR | Implantation between 2004 and 2010 | NR |

| Abou el ela et al, 201586 | Missouri, USA | HeartMate II and Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case series | 363 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 2009 and 2013 | NR |

| Akhter et al, 201534 | Wisconsin, USA | HeartMate II (120) Heart-Ware HVAD (1) DeBakey Micro-Med (1) | Retrospective, case series | 122 | 53 (12.9) | 77.0 | NR | ICM (43.6) | 370 (336) d | Implantation between 2007 and 2013 | NR |

| Birks et al, 201587 | Multicenter | Heart-Ware HVAD | Registry study | 332 | 52.7 (11.9) | 71.1 | White (68.7) African American (26.7) |

BTT (100) ICM (36.7) |

NR | Secondary analysis of ADVANCE BTT and CAP trial, ≥6 mo follow-up | NR |

| Fried et al, 201511 | New York, USA | HeartMate II, Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case series | 298 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 2008 and 2014 | NR |

| Fudim et al, 201588 | Tennessee, USA | Heart-Ware HVAD, Heart-Mate II | Retrospective, case series | 161 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 2009 and 2014 | NR |

| Haeck et al, 201589 | Leiden, Netherlands | Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case series | 16 | 61 (8) | 81.0 | NR | DT (100.0) ICM (81.0) |

NR | Consecutive LVAD implants | NR |

| Haglund et al, 201545 | Tennessee, USA | HeartMate II, Heart-Ware HVAD | Registry study | 81 | 52.6 (10.6) | 78.0 | NR | BTT (100.0) | NR | Patients in the Vanderbilt Advanced Heart Failure Registry | DT, died before the index hospitalization, implantation with temporary or pulsatile LVAD, RVAD, or TAH |

| Harvey et al, 201590 | Minnesota, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, cohort | 230 | 57.0 (14.0) | 80.4 | NR | BTT (80.4) DT (19.6) |

NR | Implantation between 2006 and 2013 | NR |

| Henderson et al, 201591 | Illinois, USA | CF LVAD | Retrospective, cohort | 56 | 52.4 (12.5) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 2008 and 2014 | NR |

| Imamura et al, 201513 | Japan | Evaheart, Dura-Heart, HeartMate II, Jarvik 2000, Heart-Ware HVAD |

Retrospective, cohort | 57 | 40.0 (12.0) | 79.0 | Asian (100.0) | BTB (9.0) ICM (5.0) |

421 (325) d | NR | Driveline infection before first discharge |

| Krishna-moorthy et al, 201492 | North Carolina, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 5 | 63.0 (12.2) | 100.0 | NR | DT (100.0) ICM (80.0) |

NR | CIED lead removal after LVAD implant and ISHLT- defined LVAD infection | NR |

| Lushaj et al, 201593 | Wisconsin, USA | HeartMate II, Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case series | 128 | 57.8 | 84.3 | NR | DT (32.6) BTT (67.4) ICM (22.6) |

NR |

Between 1/2008 and 6/2014 | NR |

| Majure et al, 20159 | District of Columbia, USA | HeartMate II, Heart-Ware HVAD | Retrospective, case series | 141 | 54.6 (13.6) | 74.0 | African American (61.7) Other races not specified |

DT (36.1) BTT (63.9) ICM (35.0) |

NR | Implantation between 2011 and 2014 | Death before discharge |

| Maltais et al, 201594 | Multicenter | Heart-Ware HVAD | Registry study | 382 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Secondary analysis of ADVANCE BTT and CAP trial | NR |

| Matsumoto et al, 201510 | Osaka, Japan | Evaheart, Heart-Mate II | Retrospective, cohort | 39 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 2007 and 2014 | NR |

| McCandless et al, 201595 | Utah, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, cohort | 57 | 56 (14.6) | 87.7 | NR | DT (25.0) BTT (75.0) |

302 (302) d | Utah Artificial Heart Program Database, between 2008 and 2012 | NR |

| McMenamy et al, 201596 | Sydney, Australia | CF LVAD | Retrospective, cohort | 85 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 2010 and 2014 | NR |

| Nishinaka et al, 201518 | Japan | Evaheart | Registry review | 108 | 42.0 (19) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Advanced heart failure, J-MACS registry | NR |

| Ono et al, 201597 | Japan | HeartMate II | Registry review | 104 | 41.7 | 76.0 | NR | BTT (100) | 299.2 d | J-MACS registry between 2013 and 2014 | NR |

| Potapov et al, 201598 | Europe | HeartMate II | Retrospective, cohort | 479 | NR | NR | NR | ICM (46.6) DCM (49.5) |

610 (592) d | Implant done at 1 of 3 high-volume European centers between 2006 and 2014 | NR |

| Trachtenberg et al, 201422 | Texas, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 149 | 55.4 (13) | 76.0 | NR | ICM (59.1) | 642 (531) d | Implantation between 2008 and 2012 | NR |

| Tsiouris et al, 201599 | Connecticut, USA | HeartMate II (136) Heart-Ware HVAD (13) | Retrospective, cohort | 149 | 53.7 (12.1) | 74.0 | White (59.0) African American (41.0) |

BTT (54.3) DT (45.7) ICM (37.0) NICM (63.0) |

435.7 (392.2) d | Implantation between 2006 and 2013 | NR |

| Van Meeteren et al, 201512 | USA | NR | Registry review | 734 | 57, median | 78.6 | NR | NR | NR | Hospital in Mechanical Circulatory Support Registry Network, between 2004 and 2014 | NR |

| Wus et al, 2015100 | Pennsylvania, USA | HeartMate II | Retrospective, case series | 68 | 57 (11.4) | 80.9 | White (60.3) Other races not specified |

NR | NR | First implant | No ICU-intermediate care–discharge pathway, implant at outside hospital, OHT during index hospitalization, never left ICU, had pump exchange |

| Yoshioka et al, 2014101 | Osaka, Japan | Jarvik 2000 | Retrospective, case series | 9 | 57 (11.0) | 77.8 | NR | DT (22.8) BTT (77.2) |

725 d, median | NR | NR |

| Yost et al, 201519 | Illinois, USA | NR | Retrospective, case series | 134 | 58 (13.1) | 73.1 | NR | NR | NR | Implantation between 2012 and 2014 | NR |

Abbreviations: ADVANCE, Ventricular Assist Device for the Treatment of Advanced Heart Failure; BTB, bridge to bridge; BTC, bridge to candidacy; BTD, bridge to destination therapy; BTT, bridge to transplant; CAP, continuous-access protocol; CF, continuous flow; CIED, cardiovascular implantable electronic device; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DT, destination therapy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; IABP, intraaortic balloon pump; ICM, ischemic cardiomyopathy; ICU, intensive care unit; INTERMACS, Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support; ISHLT, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplant; IV, intravenous; J-MACS, Japanese Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; NICM, nonischemic cardiomyopathy; NR, not recorded; OHT, orthotopic heart transplant; PE, pulmonary embolus; PPM, peripartum cardiomyopathy; RV, right ventricular; RVAD, right ventricular assist device; TAH, total artificial heart.

Data presented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range)

Table 3.

Infection and Outcome Data

| Study | Incidence of Infection | Type of Infection | Outcome of Infection | Outcome of Treatment | Microorganisms | Comments/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miller et al, 200746 | 19 LVAD infections | DLI, 100.0% | NR | NR | NR | Pacemaker lead-related infections occurred later in the course of treatment |

| Schulman et al, 200724 | 11 LVAD infections | DLI, 18.8% BSI, 63.6% Endocardial infection, 9.1% |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Struber et al, 200816 | 24 LVAD infections | 0.37 DLI/patient y | Of 21 DLI, 6 recurred; no mortality associated with DLI | NR | NR | NR |

| Morshuis et al, 200947 | 24 infections 18 LVAD infections | DLI, 72% PPI, 28% |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Lahpor et al, 201048 | NR | 0.19–0.61 DLI/patient y 0.07–0.09 PPI/patient y |

0.13–0.62 deaths attributable to infection | NR | NR | Combined results of 3 studies |

| Topkara et al, 201032 | 42 patients with at least 1 episode of infection (number of infections not specified) | PPI, 78.0% DLI, 22.0% 8.6% developed Clostridium difficile infection |

Sepsis (18.5%) associated with decreased survival Overall mortality from LVAD infections, 19.7% |

1 patient required LVAD explantation | DLI: MRSA (27.2%) Pseudomonas aeruginosa (18.1%) MSSA (9%) Serratia marcescens (9%) Citrobacter koseri (9%) Enterobacter cloacae (9%) Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (9%) Klebsiella pneumonia (9%) PPI: MRSA, 1 (16.6%) CoNS, 2 (33.3% P aeruginosa, 1 (16.6%) C koseri, 1 (16.6%) N sicca, 1 (16.6%) |

Infection was associated with greater length of hospital stay and mortality |

| Wieselthaler et al, 201049 | 16 infections 8 LVAD infections |

DLI, 100% | NR | 7 treated with antimicrobial agents alone; 1 treatment failed and debridement required |

NR | NR |

| Bogaev et al, 201139 | 89 patients with at least one infection (number of infections not specified) | 20 LVAD infections; subtypes not specified | NR | NR | NR | Excluded transient bacteremia |

| Garbade et al, 201150 | 6 LVAD infections | Only DLI reported | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| John et al, 201125 | 22 LVAD infections | DLI, 100.0% | NR | NR | NR | Before FDA device approval, the rate of driveline infection was 26.3%, which decreased to 18.8% after FDA approval |

| John et al, 201151 | 1,113 infections in 556 patients | 303 LVAD infections: PPI, 33 BSI, 233 Endocardial, 5 Line sepsis, 41 Other, 386 |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Schaffer et al, 201115 | 140 infections 68 LVAD infections |

DLI, 30.0% PPI, 28.0% Sternal wound, 2% |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Starling et al, 201125 | 142 infections | DLI, 31.7% PPI, 2.8% BSI, 33.1% Line sepsis, 1.4% Other, 60.5% |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aggarwal et al, 201220 | 30 infections | BSI only | BSI was associated with increased risk of hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke | NR | CoNS, 47.1% Candida spp, 8.8% Enterococcus faecalis, 8.8% Achromobacter xylosoxidans, 5.9% MRSA, 5.9% MSSA, 5.9% Bacillus spp, 2.9% Corynebacterium spp, 2.9% E cloacae, 2.9% P aeruginosa, 2.9% Streptococcus mitis, 2.9% Other Streptococcus spp, 2.9% |

The study aim was to show sex differences in LVAD complications; higher strokes and fewer infections were reported for women |

| Brewer et al, 201252 | 230 LVAD infections | NR | NR | NR | NR | Sepsis and device-related infections increased as BMI increased to >35 |

| Bomholt et al, 201153 | 55 infections in 12 patients | DLI, 55 No BSI, PPI, or others reported |

All patients treated with antibiotics alone; no LVAD explantations | Patients had 1–8 relapses, but none required device explantation |

Staphylococcus aureus (33%) Corynebacterium spp (15%) E faecalis (13%) E coli (14%) Klebsiella spp (7%) E cloacae (3%) Proteus spp (3%) |

Infection rates were low, and those that occurred were easily managed |

| Chamogeorgakis et al, 201227 | 34 infections | DLI, 26 (67.0%) PPI, 8 (21.0%) |

2 deaths, both in patients with infections managed with medical therapy | 5 patients had device exchange; 2, device removal; 1, recurrence; 6 infections required surgical débridement |

S aureus (33%) CoNS (7%) Pseudomonas spp (27%) Klebsiella spp (7%) Serratia spp (7%) Proteus spp (7%) Candida spp (7%) |

Major risk factor for recurrence was continued device need; recommended a workup to determine if device reimplantation was necessary after explantation in all cases |

| Donahey et al, 201231 | 17 MDRO LVAD infections |

NR | Infections were associated with longer length of stay but not mortality | NR | MRSA was the most common MDRO | Risk factors for MDRO included exposed driveline, hospital length of stay, and age |

| Eleuteri et al, 201254 | 23 infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | Study included implementation of a driveline grading system–based approach to site care, with a significant drop in driveline infection rate (36.3% to 16.0%) |

| Fleissner et al, 201229 | 20 infections | DLI, 100% | No association was observed between LVAD infections and mortality | 11 infections were treated medically, with 3 treatment failures requiring device explantation | 37 isolates in 20 DLI S aureus (6/37) Staphylococcus epidermidis (7/37) Staphylococcus warneri (1/37) Staphylococcus lugdunensis (1/37) Staphylococcus haemolyticus (1/37) S mitis (1/37) Staphylococcus dysgalactieae (1/37) Proteus mirabilis (4/37) Proteus vulgaris (1/37) Corynebacterium spp (8/37) Granulicatella spp (1/37) Enterococcus spp (3/37) Pseudomonas spp (1/37) Escherichia spp (1/37) |

Increased rates of infection associated with obesity, very low ejection fraction, use of fresh frozen plasma during surgery, and not double tunneling the driveline |

| Goldstein et al, 201230 | 239 infections in 197 patients | DLI, 100% (percutaneous site) | 23 deaths, 6 with sepsis In multivariate analysis, LVAD infection was associated with younger age and did negatively impact survival |

20% of infections were associated with sepsis; pneumonia was the most common nondevice-associated infection | NR | Prolonged LVAD use was positively associated with infection, with 19% of patients developing an LVAD infection by 12 mo of support |

| Guerrero-Miranda et al, 201255 | 9 LVAD infections in patients with axial-flow LVADs; 0 in patients with centrifugal flow devices | NR | NR | NR | NR | Infections decreased (LVAD and non-LVAD–related) with the later generation of continuous-flow devices (vs pulsatile and axial devices) |

| Hozayen et al, 201256 | 9 LVAD infections | DLI, 100.0% | NR | NR | NR | Foam dressing was noninferior to gauze for preventing infection and was associated with higher caregiver satisfaction |

| Kamdar et al, 201557 | 294 LVAD infections | DLI, 80.0% PPI, 6.8% BSI, 12.6% |

NR | NR | NR | Younger age and prior bypass grafting were risk factors for infection |

| Krabatsch et al, 201258 | 37 LVAD infections | DLI, 75.7% BSI, 24.3% |

5.3% of infections progressed to sepsis | NR | NR | NR |

| Maiani et al, 201259 | 3 episodes of sepsis in the first 12 mo after device implantation | NR | NR | NR | NR | INTERMACS score correlated with mortality and infection |

| Mano et al, 201260 | Rates of infection varied from 19%–25% among groups (stratified by body surface area) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Lower BMI was associated with more nondevice-related infections |

| Menon et al, 201261 | 2 LVAD infections | DLI, 100% | 1 death | 1 successful débridement, device retained | S aureus 2 (100%) | NR |

| Park et al, 201262 | 383 infections 257 LVAD infections |

DLI, 27% PPI, 7% BSI, 28% Other LVAD, 30% non-LVAD, 45% |

NR | NR | NR | Risk of infection decreased midtrial vs early |

| Popov et al, 201263 | 5 infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Schibilsky et al, 201264 | 7 LVAD infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | Fewer superficial, late DLI in the double-tunnel group compared with the conventional group |

| Tarzia et al, 201265 | NR | DLI, 5 | NR | NR | NR | Postauricular gable and intraventricular pump appeared to be associated with reduced local and systemic infections compared with prior studies of LVAD infections |

| Aldeiri et al, 201321 | 33 infections, 19 LVAD-related |

NR | P aeruginosa BSI associated with stroke | NR | NR | NR |

| Choudhary et al, 201328 | 56 LVAD-related infections | DLI, 91% PPI, 5% |

Survival not impacted by infection | NR | 15 Pseudomonas organisms | S aureus infections tended to occur earlier than infections of other organisms, particularly Pseudomonas spp |

| Forest et al, 201323 | 27% of patients had at least 1 episode of infection (some recurrent) | DLI, 30% 43% of patients with DLI had bacteremia |

Bacteremia did not impact long-term survival, but BSI was associated with longer hospital stay | NR | 41% of organisms were Staphylococcus spp | NR |

| Haj-Yahia et al, 200766 | 32 infections, 6 LVAD-associated | DLI or PPI, 100% | Infection was a leading cause of readmission | NR | NR | NR |

| Lalonde et al, 201367 | 1.2 (1) infections/patient, including 16 episodes of pneumonia, 10 episodes of urinary tract infection | DLI, 11 episodes BSI, 5 episodes | 30-day mortality from LVAD infections, 10.9% | NR | NR | Infection rates were comparable between HeartWare HVAD and HeartMate II |

| Nienaber et al, 201336 | 101 LVAD infections in 78 patients | DLI, 36.6% PPI, 4.0% BSI, 35.6% Cannula infection, 10.9% Mediastinitis, 5.0% CIED, 3.9% |

NR | 14% of infections required débridement; only 3 required device explant | NR | Candidemia was associated with poor outcome DLI was associated with prolonged therapy and destination therapy. Most superficial infections did not progress to deep infection Outcomes improved with CIED removal for concomitant LVAD/CIED infection |

| Slaughter et al, 201368 | 145 LVAD infections | DLI, 51.7% Sepsis, 48.3% |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Smedira et al, 201317 | 68 infections 51 LVAD infections |

DLI, 55.0% PPI, 19.6% Septic emboli (device), 7.8% BSI, 5.8% |

Infection was the leading cause of readmission | NR | NR | NR |

| Stulak et al, 201369 | NR | DLI, 41 infections 7 infections required device exchange |

NR | NR | NR | Study compared prophylactic antibiotics to reduce DLI; no effect noted |

| Tong et al, 201326 | 47 LVAD infections | PPI ± DLI, 23.4% DLI, 76.6% |

NR | 8 pump exchanges, 11 irrigation and debridement of the driveline or pump | 10 patients had isolated bacteremia of no clinical significance; 90% were GPC; 43% of infections were gram positive, 43% gram negative, and 15% anaerobic |

Study of late onset infection; late infections occurred in 20% of patients and were associated with worse survival |

| Wu et al, 201370 | 66 infections | DLI, 27.3% | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Baronetto et al, 201440 | None | NR | NR | NR | NR | Primary purpose was to evaluate the use of a stat-lock and chlorhexidine disc to prevent infection |

| Cagliostro et al, 201441 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 76.3% of patients with a standard dressing did not have a driveline infection vs 88.6% with silver dressing |

| Chan et al, 201471 | 11 infections | DLI, 100% | NR | All patients treated medically, 4 relapses | MSSA (27.6%) CoNS (20.7%) |

Pus or discharge was present in 89% of patients |

| Cogswell et al, 201472 | 11 infections | DLI, 100% | Mortality was higher in patients who abused substances | NR | NR | Odds ratio was 5.4 for driveline infection in patients who were substance abusers |

| Dean et al, 201473 | 39 infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | Leaving the velour portion of the driveline was associated with fewer infections compared with data from the original HeartMate II DT trial |

| Hieda et al, 201474 | 27 LVAD-associated infections | DLI, 55.6% BSI, 44.4% |

No deaths | No medical therapy failed; no transplants required | MRSA, 48 (11.9%) MSSA, 39 (9.7%) Staphylococcus anginosus, 5 (1.2%) Staphylococcus capitis, 10 (2.5%) Staphylococcus caprae, 5 (1.2%) S epidermidis, 45 (11.1%) S haemolyticus, 4 (1.0%) S lugdunensis, 26 (6.4%) α-Streptococcus spp 9 (2.2%) Staphylococcus spp 14 (3.5%) Corynebacterium spp 28 (6.9%) K pneumonia, 39 (9.7%) E coli, 38 (9.4%) E aerogenes, 16 (4.0%) S maltophilia, 7 (1.7%) E faecalis, 22 (5.4%) M morganii, 18 (4.5%) C freundii, 18 (4.5) P fluorescens, 4 (1.0%) S marcescens, 9 (2.2%) |

Gram-negative bacilli were rarely isolated from the exit site |

| Jennings et al, 201475 | 17 infections in 16 patients | DLI, 13 PPI, 1 BSI, 3 |

NR | Chronic suppression with antibiotics failed in 5 patients; 3 devices had to be explanted | MRSA, 3 (12%) MSSA, 5 (20%) S marcescens, 3 (12%) P mirabilis, 1 (4%) P aeruginosa, 1 (4%) Staphylococcus maltophilia, 2 (8%) Klebsiella spp, 4 (16%) Acinetobacter spp, 1 (4%) Achromobacter spp, 2 (8%) Citrobacter spp, 1 (4%) Actinomyces spp, 1 (4%) Corynebacterium spp, 1 (4%) |

C difficile infection, 2 patients |

| John et al, 201476 | 113 infections | DLI, 49.6% | NR | NR | S aureus was the most common microorganism in DLI | DLI was associated with diabetes mellitus and higher BMI. Sepsis was associated with decreased survival |

| Jorde et al, 201477 | 192 LVAD infections | Before FDA approval, 35%; after approval, 19% | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kimura et al, 201433 | 17 LVAD infections | DLI, 94.1% BSI, 5.9% |

34% of readmissions were attributed to infection; 8 episodes progressed to sepsis | NR | S aureus predominated (6 of 8 culture-positive sepsis episodes) | NR |

| Koval et al, 201478 | 89 LVAD infections | DLI, 100% (study was of DLI only) | DLI was associated with a decreased rate of survival | 1/3 of superficial infections progressed despite conservative therapy | S aureus and Pseudomonas spp were responsible for 1/3 of infections | When there was recurrent infection with a new organism, gram-positive infections occurred after gram-negative infections and vice versa |

| Kretlow et al, 201414 | 26 patients with at least 1 LVAD infection | DLI, 42.3% PPI, 50.0% Endocardium, 8.0% |

Successfully treated infections had 29% mortality compared with 67% mortality of treatment failures | 1 device was explanted; the patient survived |

P aeruginosa, 9 (19.6%) E coli, 5 (10.9%) VRE, 4 (8.7%) S marcescens, 4 (8.7%) S maltophilia, 4 (8.7%) CoNS, 3 (6.5%) E cloacae, 2 (4.3%) MSSA, 2 (4.3%) MRSA, 1 (1.0%) Acinetobacter baumannii, 1 (2.2%) Actinomyces spp, 1 (2.2%) Candida albicans, 1 (2.2%) C koseri, 1 (2.2%) Eikenella corrodens, 1 (2.2%) K pneumonia, 1 (2.2%) M morganii, 1 (2.2%) N sicca, 1 (2.2%) P mirabilis, 1 (2.2%) GBS, 1 (2.2%) Viridans group streptococci, 1 (2.2%) No growth, 1 (2.2%) |

Antibiotic bead and repeat debridement was associated with infection clearance in most patients (65.3%) |

| Masood et al, 201437 | 59 LVAD infections | Exclusively DLI and PPI | NR | 0% mortality with pump exchange | NR | Pump exchange with omental transposition for confirmed PPI; had a 75% (21%) freedom from recurrence of device-related infections |

| Moazami et al, 201479 | 33 LVAD infections | DLI, 30.0% PPI, 6.0% BSI, 13.0% |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Nelson et al, 201480 | 12 patients with at least 1 LVAD infection | DLI, 50.0% Mediastinitis and LVAD exposure/erosion, 50.0% |

Multidisciplinary surgical approach achieved salvage achieved in all cases | 50% mortality noted at follow-up (post hospital discharge) | MSSA, 1 MRSA, 1 Pseudomonas spp, 4 Parvimonas spp, 1 |

Complex wounds were associated with greater mortality, even after attempted surgical salvage |

| Nishi et al, 201481 | 2 LVAD infections | DLI, 1 BSI, 1 |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Raymer et al, 201482 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | BMI >35 was associated with increased risk of infection |

| Sabashnikov et al, 20148 | 73 infections 37 LVAD infections |

DLI, 95.0% PPI, 5% |

NR | NR | 27 organisms isolated S aureus (70%) Enterobacter spp (15%) Coliform spp (44%) Pseudomonas spp (48%) Enterococcus spp (15%) Klebsiella spp (22%) S maltophilia (19%) Proteus spp (19%) Bacteroides spp (7%) Citrobacter spp (15%) S marcescens (4%) A baumannii and calcoaceticus (4%) Pantoea spp (4%) Chryseobacterium indologenes (4%) VRE, 1/27 (4%) Anaerobic spp, 1/27 (4%) MRSA, 1/27 (4%) Prevotella spp, 1/27 (4%) Peptostreptococcus spp, 1/27 (4%) Group B β-hemolytic Streptococcus, 1/27 (4%) Morganella morganii, 1/27 (4%) |

Double tunnel was not associated with fewer driveline infections HeartMate II was associated with more infections than the HeartWare HVAD |

| Singh et al, 201483 | NR | NR | NR | NR | MRSA and MSSA were the most commonly isolated organisms | DLI decreased with exposure of only the silicone velour portion of the driveline |

| Subbotina et al, 201484 | 6 infections 2 LVAD infections |

NR | Infection was associated with 33% mortality | NR | NR | NR |

| Takeda et al, 201485 | NR | DLI, 21 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Abou el ela et al, 201586 | 98 infections | DLI, 100% | NR | 22% of those with a primary revision needed a second revision |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 26% MSSA, 19% MRSA, 22% |

The combination of driveline relocation into the rectus muscle, velour removal, and wound- vacuum therapy had better outcomes |

| Akhter et al, 201534 | 32 readmissions for infection; 21 were LVAD infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | Infection was a leading cause of readmission in this cohort |

| Birks et al, 201587 | 113 infections | DLI, 49.6% | NR | NR | S aureus was the most common organism isolated in DLI | DLI rates in white vs nonwhites were similar |

| Fried et al, 201511 | 38 LVAD infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | DLI was not associated with an increased risk of stroke or device thrombosis |

| Fudim et al, 201588 | 18 infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | DLI was more common in those with external anchoring sutures, but this was not statistically significant after multivariate adjustment |

| Haeck et al, 201589 | 2 LVAD infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | Both patients with DLI required hospitalization |

| Haglund et al, 201545 | 11 infections 5 LVAD infections |

Sternal wound infection, 60% DLI/pump pocket infection, 40% |

NR | NR | NR | More infections occurred in HeartMate II patients than in HeartWare HVAD patients (0.49 [0.70] vs 0.17 [0.68]; P=.001) Infection was the second most common cause of readmission after cardiac causes |

| Harvey et al, 201590 | 60 infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | Risk of stroke was increased with infection and with postoperative sepsis |

| Henderson et al, 201591 | 27 infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | Higher BMI was associated with an increased risk of infection |

| Imamura et al, 201513 | 24 LVAD infections | DLI, 23 PPI, 3 |

NR | 1 pump exchanged (HeartMate II to Jarvik 2000) due to PPI | NR | Higher BMI was a predictor of readmission for infection |

| Krishnamoorthy et al, 201492 | 5 LVAD infections | BSI, 80% | NR | After lead extraction, 4 patients had a relapse of the BSI |

S aureus, 20% Enterococcus spp, 40% Pseudomonas spp, 20% Klebsiella spp, 20% 40% were MDRO |

CIED removal for LVAD infection is still associated with high rates of relapse of the infection and patient mortality |

| Lushaj et al, 201593 | 4 LVAD infections | NR | NR | NR | NR | BTT vs DT did not show a significant difference in infection rates |

| Majure et al, 20159 | 66 infection-related readmissions 27 LVAD-infection–related readmissions |

DLI, 39 infections | NR | NR | NR | Patients with an HVAD had a significantly higher rate of hospitalization than patients with a HeartMate II for LVAD-related infections (HR, 2.90 (95% CI, 1.03–8.13, P=.04) |

| Maltais et al, 201594 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Infection overall decreased after 30 days, with 4.23 events/patient y in the first 30 d, and 1.06 events from 30–180 d, 0.97 events from 180–365 d. DLI did not change significantly over time |

| Matsumoto et al, 201510 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Freedom from infection at 12 mo was better with the HeartMate II (85%) than the Evaheart (46.2%) |

| McCandless et al, 201595 | 4 LVAD infections | DLI, 100% | NR | NR |

S aureus, 2 Achromobacter spp, 1 S marcescens, 1 |

Fewer infections with silicone than with velour |

| McMenamy et al, 201596 | No LVAD infections | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No DLIs, even in patients with a BMI >35 |

| Nishinaka et al, 201518 | NR | 0.36 DLI/patient year 0.04 PPI/patient year |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ono et al, 201597 | NR | 43% of those with BSA <1.5 and 16% of those with ≥1.5 BSA had DLI | NR | NR | NR | Smaller BSA was associated with more DLI |

| Potapov et al, 201598 | NR | 0.08 DLI/patient year | NR | NR | NR | Authors concluded that the HeartMate II has an acceptable associated complication and infection rate |

| Trachtenberg et al, 201422 | 45 infections | 22 BSI originated from DLI 4, catheter-related BSI 4, UTI-related BSI |

Persistent bacteremia, particularly Pseudomonas, was associated with all- cause mortality and stroke | 62% of BSI persisted after treatment with appropriate antibiotics and required chronic, lifelong oral suppression |

Pseudomonas spp, 12 S aureus, 11 E faecalis, 5 Candida spp, 3 E coli, 1 K pneumoniae, 1 Other, 12 |

NR |

| Tsiouris et al, 201599 | 41 LVAD infections | DLI, 9 PPI, 1 BSI, 31 |

NR | 1 patient required a device exchange; all others treated with 6 wk of antibiotics without need for chronic suppression | DLI: S aureus, 5 CoNS, 2 Pseudomonas spp, 1 Serratia spp, 1 PPI: CoNS, 1 BSI: CoNS, 16 S aureus, 5 Enterobacter spp, 3 Klebsiella spp, 2 Serratia spp, 1 Candida spp, 2 Viridans group streptococci, 2 |

DLI infection did not alter risk of death |

| Van Meeteren et al, 201512 | 81 LVAD infections | DLI, 100% (other infections not included) | NR | DLI did not adversely affect survival or increase risk of pump thrombosis or stroke | NR |

NR |

| Wus et al, 2015100 | NR | DLI, 0 | NR | NR | NR | Driveline dressing changes varied from daily to weekly without any significant impact on DLI |

| Yoshioka et al, 2014101 | 1 LVAD infection | DLI, 100% | NR | NR | NR | DLI was late onset (2 y post implant) |

| Yost et al, 201519 | 34 LVAD infections | DLI, 32.3% PPI, 8.8% BSI, 39.1% |

NR | NR | NR | Infection rates in patients with and without delayed sternal closure were not statistically different |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BSI, bloodstream infection; CIED, cardiovascular implantable electronic device; CoNS, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus; CRI, cardiac resynchronization device; DLI, driveline infection; DT, destination therapy; GPC, gram-positive cocci; MDRO, multidrug resistant organisms; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; PPI, pump pocket infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococcus; ±, with or without.

Study reported both incidents.

Definitions

Definitions for LVAD infection were not consistent among the various registries, including in INTERMACS (10 studies), J-MACS (3 studies), and ISHLT (9 studies). One study used the Centers for Disease Control/National Healthcare Network Surveillance definitions for reporting on bloodstream infection. Two studies used their own definitions for percutaneous site infection. The remaining studies did not include precise definitions for LVAD infections.

Devices and Procedure Characteristics

The most extensively studied device was the HeartMate II, with 32 studies reporting on it exclusively. Thirteen studies described the HeartWare HVAD alone. A mix of HVAD and HeartMate II data was reported in 21 studies. Other combinations of VentrAssist, HeartMate II, Evaheart, DuraHeart, and the Micromed DeBakey were reported in eleven studies. Two reported exclusively on the DuraHeart. Three studies reported results of Jarvik 2000 implantations. One study reported on the Evaheart alone. The remaining 13 studies specified continuous flow devices but did not specify the type of device.

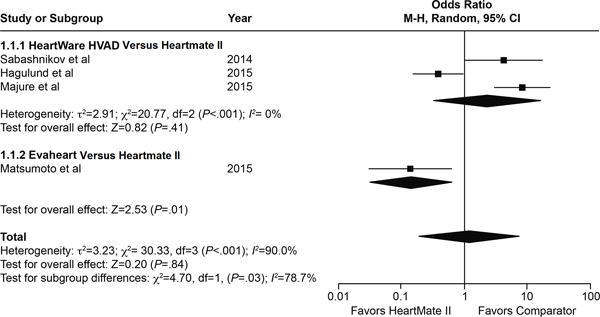

Three studies directly compared infection rates between the HeartMate II and the HeartWare HVAD. In the first study, overall infections were significantly higher (P=.02), as were percutaneous infections (P=.01) associated with the HeartMate II.8 The second study found the opposite, that is, a higher rate of infection for the HVAD than the HeartMate II.9 In another study that compared the HeartMate II to the Evaheart LVAD, the HeartMate II was associated with lower infection rates.10 These results are shown in the forest plot in Figure 2. However, the heterogeneity and small numbers of patients in these studies limited the conclusions that could be drawn from the pooled estimate. Several strategies for prophylaxis and wound dressing were discussed (Supplement 2), but none were clearly superior.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of infection rates for the HeartMate II compared with the HeartWare HVAD: data from Haglund et al45 (all types of infections, including driveline, sternal wound, and non-LVAD infections); Majure et al9 (rehospitalizations due to LVAD infections); and Sabashnikov et al8 (percutaneous site infections treated only with antimicrobial agents); and the Evaheart: data from Matsumoto et al10 (freedom-from-exit-site infection at 1 year [major endpoint], presented as number of patients with at least 1 exit-site infection in 1 year). Pooled estimates were not significant, likely because of the high degree of heterogeneity in the studies.

Infection Types

Driveline Infection

Fifty-two studies showed driveline infections to be the most common infection associated with LVADs, and it was the only infection described in several studies. Two studies found that the prognosis for a driveline infection was not particularly poor, and these infections were not associated with pump thrombosis or stroke.11,12 Another study found that driveline infections tended to occur late, at a median of 190 days postoperatively.13 In general, these infections were managed successfully with a combination of local debridement and antimicrobial therapy; LVAD removal was not necessary in most cases.

Pocket Infection

Infection of the pump pocket was the predominant infection reported in a series of patients treated with antibiotic beads plus debridement14. Pump pocket infection was nearly as common as driveline infection in 1 study15 and was usually the second most common infection in studies reporting both pump pocket infection and driveline infection.15–18 The prognosis for patients with pump pocket infection was not studied specifically in any of the included reports.

Bloodstream Infection

Although less frequently reported overall, bloodstream infections were reported in 1 study to be the most common infectious complication of LVAD implantation19. In addition, Aggarwal et al20 found bloodstream infections to be associated with increased risk of both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke; however, transient bacteremia, which was not defined, was excluded. Aldeiri et al21 also reported an association between bloodstream infection, specifically Pseudomonas bacteremia, and stroke. The risk of increased mortality, stroke, and Pseudomonas bacteremia was also reported by Trachtenberg et al.22

Sources of bacteremia were not clear. Forest et al23 reported that 43% of patients had secondary bacteremia from driveline infections. They also noted that patients with bloodstream infections were hospitalized longer than patients with driveline infections. Fungemia was not studied. Bloodstream infections were the predominant infection reported in a study by Schulman et al24 comparing pulsatile and axial flow devices. However, they did not speculate on a reason for this finding. Starling et al25 also reported a similar predominance of bloodstream infection in their LVAD patients. One study reported 10 cases of asymptomatic bacteremia, which were most often gram positive (90%) but had no other clearly unifying characteristics.26

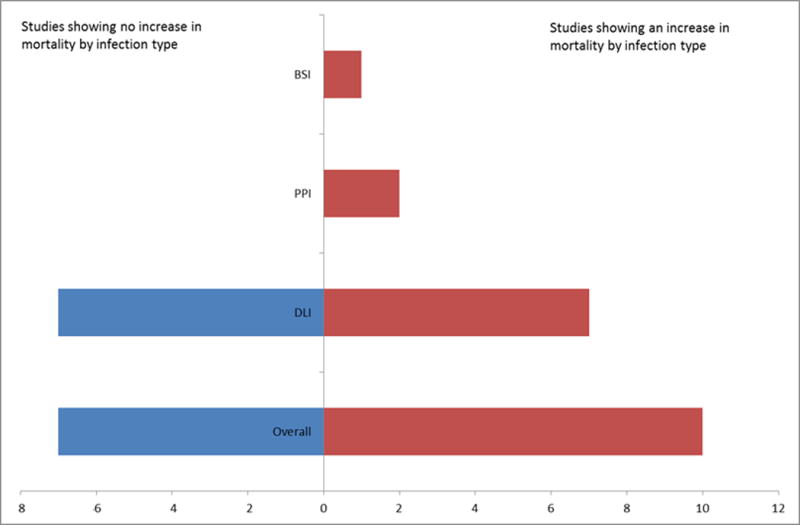

Infection Outcomes and Treatment

Studies reporting an association between infection and mortality are summarized in figure 3. Infection incidence and mortality associated with LVAD infections appeared to decrease over time, as noted in a registry study that compared rates of complications in those who received a HeartMate II before and after the device’s approval by the US Food and Drug Administration. This trend appeared to be associated with a Center’s increased experience in implanting and subsequently managing the devices, as well as with the use of smaller devices with better flow dynamics.

Figure 3.

Studies reporting an association between mortality by infection type

Chamogeorgakis et al27 noted that the most important risk factor for infection reported was a continued need for LVAD support. These authors recommended careful evaluation of the patient to ensure that support was still necessary before considering explantation followed by reimplantation.

The effect of infection on long-term patient outcomes was described in 11 studies with varying results, and two studies noted no impact of infection on long-term outcomes.28,29 Another noted a high rate of infection-associated deaths in a cohort of patients who were substance abusers. One registry study showed LVAD infections to be significantly associated with poor survival after adjusting for age and comorbidities, with 19% of patients experiencing an LVAD infection during their first year of support.30 However, two other studies did not find infection to be associated with increased mortality, although they did show increased hospital length of stay in patients with infection.23,31 LVAD infections were reported as a leading cause for readmission in 5 studies.17,32–35

The necessity of pump exchange is not clear. One study noted a particularly poor prognosis with candidemia and concomitant implantation of a cardiac implanted electronic device (CIED), and failure to remove the device during pump exchange was associated with poor outcomes.36 Another investigation noted good outcomes with pump exchange for treatment of driveline infections and pump pocket infections, with no mortality and low recurrence rates.37

One study reported a salvage protocol where, when infection was suspected, the driveline and pocket were debrided and antibiotic beads placed, followed by subsequent debridement of all infected tissues and replacement of the LVAD.14 When the culture no longer showed infection, the surgeons proceeded to definitive closure of the incision and possible flap coverage. This protocol was successful in clearing infection in 65% of patients. However, lower success rates were noted for Pseudomonas species compared with infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Candida species, and other gram-negative organisms, which were more likely to resolve.14 Causative microorganisms are discussed in Supplement 3. Other demographic risk factors examined are discussed in Supplement 4.

Study Quality

Assessments of study quality are summarized in Table 4. In general, we found a low risk for selection, performance, and detection bias. Reporting bias was more common. Attrition bias was rated as low or unclear in most studies.

Table 4.

Quality Assessments and Risk of Biasa

| Study | Risk of Selection Bias | Risk of Performance Bias | Risk of Detection Bias | Risk of Attrition Bias | Risk of Reporting Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miller et al, 200746 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Schulman et al, 200724 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Struber et al, 200816 | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Morshuis et al, 200947 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Lahpor et al, 201048 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Topkara et al, 201032 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Wieselthaler et al, 201049 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Bogaev et al, 201139 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Garbade et al, 201150 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| John et al, 201125 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| John et al, 201151 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Schaffer et al, 201115 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Starling et al, 201125 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Aggarwal et al, 201220 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Brewer et al, 201252 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Bomholt et al, 201153 | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Chamogeorgakis et al, 201227 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Donahey et al, 201231 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Eleuteri et al, 201254 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Fleissner et al, 201229 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Goldstein et al, 201230 | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Guerrero-Miranda et al, 201255 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Hozayen et al, 201256 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Kamdar et al, 201557 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Krabatsch et al, 201258 | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | High |

| Maiani et al, 201259 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Mano et al, 201260 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Menon et al, 201261 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Park et al, 201262 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Popov et al, 201263 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Schibilsky et al, 201264 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Tarzia et al, 201265 | Unclear | Low | High | Low | High |

| Aldeiri et al, 201321 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Choudhary et al, 201328 | Low | Low | Low | High | Unclear |

| Forest et al, 201323 | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Haj-Yahia et al, 200766 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Lalonde et al, 201367 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Nienaber et al, 201336 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Slaughter et al, 201368 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Smedira et al, 201317 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Stulak et al, 201369 | Low | Low | Low | High | High |

| Tong et al, 201326 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Wu et al, 201370 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Baronetto et al, 201440 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Cagliostro et al, 201441 | Unclear | Low | High | Low | Unclear |

| Chan et al, 201471 | High | High | High | Low | Low |

| Cogswell et al, 201472 | High | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Dean et al, 201473 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Hieda et al, 201474 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Jennings et al, 201475 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| John et al, 201476 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Jorde et al, 201477 | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Kimura et al, 201433 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Koval et al, 201478 | High | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Kretlow et al, 201414 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Masood et al, 201437 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Moazami et al, 201479 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Nelson et al, 201480 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Nishi et al, 201481 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Raymer et al, 201482 | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Sabashnikov et al, 20148 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Singh et al, 201483 | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Subbotina et al, 201484 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Takeda et al, 201485 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Abou el ela et al, 201586 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Akhter et al, 201534 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Birks et al, 201587 | Low | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Fried et al, 201511 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Fudim et al, 201588 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Haeck et al, 201589 | Low | Low | High | Low | High |

| Haglund et al, 201545 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Harvey et al, 201590 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Henderson et al, 201591 | High | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Imamura et al, 201513 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High |

| Krishna-moorthy et al, 201492 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Lushaj et al, 201593 | Low | Low | High | Low | High |

| Majure et al, 20159 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Maltais et al, 201594 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Matsumoto et al, 201510 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| McCandless et al, 201595 | High | High | Unclear | Low | Low |

| McMenamy et al, 201596 | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | High |

| Nishinaka et al, 201518 | Low | Low | High | Low | High |

| Ono et al, 201597 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Potapov et al, 201598 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Trachtenberg et al, 201422 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Tsiouris et al, 201599 | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | High |

| Van Meeteren et al, 201512 | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Wus et al, 2015100 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Yoshioka et al, 2014101 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Risk of bias was assessed using the tool in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews7.

Discussion

Despite substantial heterogeneity across studies, we can draw a few conclusions from the data. First, driveline infections are the most common type of LVAD infection described in the literature. This finding is consistent with what is reported in the INTERMACS database, where driveline infections in continuous-flow LVADs are reported to occur at 1.31 per 100 patient months early (first three months post implantation) and 1.42 per 100 patient months late. The most common types of infections are early pulmonary infections (4.58/100 patient months) and early urinary tract infections (3.36/100 patient months), neither of which are strictly device-related.38

Second, bloodstream infection is a serious complication of LVAD implantation. Two studies found an association between stroke and bloodstream infection.20,21 Managing bloodstream infections in LVAD recipients are controversial. Most treating physicians opt for chronic, suppressive antibiotic therapy when the LVAD is clearly the source of infection; however, the best approach for managing a severe bloodstream infection from secondary sources in LVAD recipients is unclear. There is also no data to guide selection of agents for chronic suppression.

Third, and perhaps most important, we have identified a number of knowledge gaps that need to be addressed in future research. Most patients were white men; therefore, more research is needed to determine the incidence and outcomes of infections in women and minorities. The only study to specifically describe sex differences reported that women had fewer infections, but the reasons were not known.39 Preventive strategies were also not well defined. A chlorhexidine disc and sutureless fixation device appeared promising in 1 study, but the patient cohort was too small to generalize the conclusions.40 Likewise, the degree of detail in the study about silver dressings41 makes it difficult to form a strong conclusion about the true benefit of this preventive strategy. Finally, demographic risk factors are poorly understood. Hyperbilirubinemia (>6 mg/dL) was associated with 100% mortality in one study (103). The variable immunologic effects related to foreign material in the devices also complicates understanding of these effects on LVAD patients. One study, for example, found that procalcitonin values were of limited use because of the SIRS-type (systemic inflammatory response syndrome) most patients have after initial LVAD implantation.42

Drawing conclusions was difficult because existing data reporting standards and criteria used for defining LVAD infections are somewhat disparate. INTERMACS tracks major infections, defined as fever, drainage, or leukocytosis treated with nonprophylactic antimicrobial agents. Infections are classified into four general categories: localized non-device infection, percutaneous/pocket infection, internal pump-component infection, and sepsis. The ISHLT provides the second, most commonly used set of definitions, where infections are generally classified as VAD-specific, VAD-related, and non-VAD infections; and they further categorize infection by the area affected. However, this classification scheme does not differentiate between a bloodstream infection where a VAD is the definite source of bacteremia (LVAD-related bloodstream infection) and cases where the source of bloodstream infection in LVAD recipients is unclear (LVAD-associated bloodstream infection). More precise definitions are needed to accurately classify these complex infection syndromes.

The strategy for treating infection varied among the studies. We did not include 1 study in the review because it did not specify if pulsatile devices were used. In that study, however, transvenous lead extraction was associated with improved survival to transplant for those with bloodstream infection related to CIED infections or lead endocarditis.43 Levy et al44 reported that pump exchange was effective in eliminating persistent driveline infection. In this case series, antimicrobial beads were not efficacious. In general, data suggested that driveline infections can be managed in most patients with local debridement of the exit site combined with a defined course of pathogen-directed antimicrobial therapy. Device or pocket infections are typically managed with chronic, suppressive antimicrobial therapy. Emerging strategies may make more conservative local debridement with the use of negative-pressure wound dressing or other such interventions viable options in the near future. However, an LVAD exchange may be necessary if infection cannot be controlled, if relapses occur while the patient is taking suppressive antibiotic therapy or if oral suppressive therapy is not feasible (e.g., a resistant organism). There are not enough published data to make recommendations for managing bloodstream infections in patients with LVADs.

Limitations

Two important factors impacted study quality: the lack of uniform criteria to define LVAD infections and the reuse of existing data in the published literature, leading to substantial duplication of results. Study duplication is acknowledged by most investigators. In this extensive, secondary data analysis of the literature for LVAD infections, most of the published data on epidemiology and management are drawn from a relatively small number of patients. By contacting the authors and combining studies whenever duplication could be identified, we attempted to limit this effect. However, especially for the registry studies, this is a major limitation in this meta-analysis.

Conclusions

LVAD infections are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in LVAD recipients. Most published data describe driveline infections. Bloodstream infections have not been well studied and may be linked to poorer outcomes. Current evidence is inadequate to rationally guide prevention, treatment, and chronic suppression of infections. With the approval of more continuous-flow pumps, the numbers of patients with implanted LVADs will certainly increase, as will LVAD-related and LVAD-associated infections. How to manage infectious complications definitely needs further study. Collaborative initiatives and registries that track infections and treatments may yield insights into how to address this growing problem.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Patients’ Comorbiditiesa

| Study | BMI (kg/m2) | INTERMACS Score | Cardiac Resynchronization Device, % | Diabetes Mellitus, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miller et al, 200746 | 26.8 (5.9) | NR | NR | NR |

| Schulman et al, 200724 | NR | NR | NR | 37.0 |

| Struber et al, 200816 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Morshuis et al, 200947 | NR | NR | CRT, 82 | NR |

| Lahpor et al, 201048 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Topkara et al, 201032 | 28.0 (5.6) | NR | NR | 33.3 |

| Wieselthaler et al, 201049 | 27.6, mean | NR | 69.6 | NR |

| Bogaev et al, 201139 | NR | NR | CRT, 49.4 ICD, 76.3 |

NR |

| Garbade et al, 201150 | NR | 1.7 (0.74) | NR | NR |

| John et al, 201125 | 28.7 (6.8) | 3.6 (1.7) | NR | 28.4 |

| John et al, 201151 | 28.4 (9.1) | 2.5 (2.9) | NR | NR |

| Schaffer et al, 201115 | 28.3 (7.0) | 2.6 (1.0) | 80.2 | NR |

| Starling et al, 201125 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aggarwal et al, 201220 | 27.26 (6.4) | NR | NR | NR |

| Brewer et al, 201252 | 26.5 (5.9) | NR | 53.1 | NR |

| Bomholt et al, 201153 | 24.2 (21.1–27.3) | NR | CRT, 83.9 (ICD, 25/31; CRT-P, 1) |

16.1 |

| Chamo-georgakis et al, 201227 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Donahey et al, 201231 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Eleuteri et al, 201254 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Fleissner et al, 201229 | 26.9 (4.6) | NR | ICD, 100.0 | 14.8 |

| Goldstein et al, 201230 | NR | NR, although noted not to be a significant predictor of infection risk | NR | NR, although noted not to be a significant predictor of infection risk |

| Guerrero-Miranda et al, 201255 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Hozayen et al, 201256 | 29.5 (6.1) | NR | NR | 39.7 |

| Kamdar et al, 201557 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Krabatsch et al, 201258 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Maiani et al, 201259 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mano et al, 201260 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Menon et al, 201261 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Park et al, 201262 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Popov et al, 201263 | 26.0 (6.0) | NR | NR | 21.0 |

| Schibilsky et al, 201264 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Tarzia et al, 201265 | NR | 3.1 | NR | NR |

| Aldeiri et al, 201321 | 28.5 (7.0) | NR | NR | 46.3 |

| Choudhary et al, 201328 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Forest et al, 201323 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Haj-Yahia et al, 200766 | NR | NR | NR | 34.0 |

| Lalonde et al, 201367 | 24.1 (5.1) | 3.2 (0.7) | NR | 23.9 |

| Nienaber et al, 201336 | 29.4 (6.1) | NR | 87.0 | 39.0 |

| Slaughter et al, 201368 | 28.2 (6.1) | 3 (2–3) | NR | NR |

| Smedira et al, 201317 | 27 (6.0) | NR | NR | 38.0 |

| Stulak et al, 201369 | NR | NR | NR | 21.0 |

| Tong et al, 201326 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Wu et al, 201370 | 25.8 (5.1) | 2 (1–3) | 54.6 | 28.4 |

| Baronetto et al, 201440 | 24.4 | Median 3 (range, 2–4) | 78.2 | 13.0 |

| Cagliostro et al, 201441 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Chan et al, 201471 | >25, 81% overweight | NR | NR | NR |

| Cogswell et al, 201472 | 30 (7.5) | 3.6 (1.9) | NR | 15.0 |

| Dean et al, 201473 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Hieda et al, 201474 | NR | NR | 0 | NR |

| Jennings et al, 201475 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| John et al, 201476 | 28.2 (6.1) | NR | NR | NR |

| Jorde et al, 201477 | NR | NR | NR | 44.2 |

| Kimura et al, 201433 | NR | 2.2 (0.8) | NR | NR |

| Koval et al, 201478 | 28 (5.9) | 2.5 (3.3) | NR | NR |

| Kretlow et al, 201414 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Masood et al, 201437 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Moazami et al, 201479 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Nelson et al, 201480 | 29.3 (8.0) | NR | NR | 58.3 |

| Nishi et al, 201481 | NR | 2.3 (0.5) | NR | NR |

| Raymer et al, 201482 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sabashnikov et al, 20148 | 26.0 (5.0) | 2.4 (1.1) | 46.0 | 13.0 |

| Singh et al, 201483 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Subbotina et al, 201484 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Takeda et al, 201485 | NR | NR | 82.9 | 31.4 |

| Abou el ela et al, 201586 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Akhter et al, 201534 | NR | 3.0, median | NR | 26.7 |

| Birks et al, 201587 | 28.2 (6.1) | NR | NR | NR |

| Fried et al, 201511 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Fudim et al, 201588 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Haeck et al, 201589 | NR | 3.4 (1.3) | 75.0 | 25.0 |

| Haglund et al, 201545 | 28.8 (5.5) | 2.9 (1.0) | NR | 41 |

| Harvey et al, 201590 | NR | NR | NR | 34.2 |

| Henderson et al, 201591 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Imamura et al, 201513 | 20.5 (2.9) | 2.5 (0.6) | 42.0 | 3.5 |

| Krishna-moorthy et al, 201492 | 31 (6.3) | NR | 100.0 | 60.0 |

| Lushaj et al, 201593 | 28.2 (5.6) | 2.7 | 81.3 | 40.6 |

| Majure et al, 20159 | 28.3 (5.9) | NR | NR | 37.5 |

| Maltais et al, 201594 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Matsumoto et al, 201510 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| McCandless et al, 201595 | 26.8 (5.0) | NR | NR | NR |

| McMenamy et al, 201596 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Nishinaka et al, 201518 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ono et al, 201597 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Potapov et al, 201598 | NR | 2 (1–3) | NR | NR |

| Trachtenberg et al, 201422 | 28.4 (7.1) | NR | NR | 46.3 |

| Tsiouris et al, 201599 | 28.4 (5.6) | 2.8 (1.1) | 25.3 | 45.0 |

| Van Meeteren et al, 201512 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Wus et al, 2015100 | 28.6 (5.9) | NR | NR | 39.0 |