Abstract

Introduction

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) has been used to characterize substance use among adult populations; however, little is known about the validity of EMA and the patterns and predictors of substance use among older adults with and without HIV infection.

Methods

Thirty- five (22 HIV-positive, 13 HIV-negative) older adults aged 50–74 were assessed for 14 days and completed up to four smartphone-based surveys per day.

Results

Participants completed an average of 89.5% of possible EMA surveys. EMA self-reported alcohol and cannabis use were significantly positively correlated with laboratory-assessed, self-reported days of alcohol (r=0.52, p=0.002) and cannabis (r=0.61, p<0.001) used and quantity of alcohol (r=0.42, p=0.013) and cannabis (r=0.41, p=0.016) used in the 30 days prior to baseline assessment. In a subset of 15 alcohol or cannabis users, preliminary analyses of the effects of mood and pain on alcohol or cannabis use showed: 1) greater anxious mood predicted substance use at the next EMA survey (OR=1.737, p=0.023), 2) greater happiness predicted substance use later in the day (OR=1.383, p<0.001), and 3) higher pain level predicted substance use earlier in the day (OR=0.901, p=0.005).

Conclusions

Findings demonstrate that EMA-measured alcohol and cannabis use has convergent validity among older adults with and without HIV infection. Preliminary results showing predictors of substance use highlight the importance of gathering EMA data to examine daily variability and time-dependent antecedents of substance use among this population.

Keywords: Ambulatory assessment, substance use, proximal risk factors, real-world setting, aging, HIV/AIDS

1. Introduction

Smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment (EMA) - which involves brief frequently repeated surveys delivered on a mobile device such as a smartphone - has enhanced understanding of substance use patterns and the contexts and day-to-day use associated with substance use in adult samples. Empirical research, however, is limited on the use of EMA to characterize substance use in older adults, especially those with varying health statuses (e.g., HIV infection). As the population is aging at an unprecedented rate, there is a need to more accurately identify patterns of substance use and consequences of misuse among older adults, especially those with chronic illnesses known to be associated with substance use problems (e.g., HIV).

Although rates of current substance use disorders are lower among older adults compared to the general population (Kuerbis, Sacco, Blazer, & Moore, 2014; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2012), older adults present with many risk factors for subsyndromal levels of substance use and subsequent detriments to health. For example, older adults are at greater risk for loneliness, reduced social support, social isolation, and multiple chronic illnesses (Cornwell & Waite, 2009; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001; Salive, 2013), all of which are associated with increased emotional distress (e.g., anxiety, depression, stress; Cacioppo, Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2006; Katon, Lin, & Kroenke, 2007), physical pain (Jaremka et al., 2014), and using alcohol and substances to cope (Mannes et al., 2016; Mauro, Canham, Martins, & Spira, 2015; Peirce, Frone, Russell, Cooper, & Mudar, 2000). Furthermore, older adults are more vulnerable to damaging effects of alcohol and other substances compared to younger adults due to both direct (e.g., neuronal receptor sensitivity, interactions with prescribed medications; Dowling, Weiss, & Condon, 2008; Kennedy, Efremova, Frazier, & Saba, 1999; A. A. Moore, Whiteman, & Ward, 2007) and indirect (e.g., medication non-adherence; Parsons, Starks, Millar, Boonrai, & Marcotte, 2014) effects and drug interactions, emphasizing the importance of assessing subsyndromal levels of substance use among this older population.

Alcohol and cannabis are the two most commonly used substances among older adults (Blazer & Wu, 2009; Mattson, Lipari, Hays, & Van Horn, 2013), and prevalence of use continues to increase with the aging baby boomer population and legalization of marijuana in many states (Dawson, Goldstein, Saha, & Grant, 2015). Both alcohol use and recreational cannabis use have been associated with greater loneliness and related emotional distress among older adults (Kuerbis et al., 2014; Mannes et al., 2016). Studies have also shown that older adults commonly use alcohol and/or cannabis specifically to cope with stress and mood (Mauro et al., 2015). Notably, studies also find that higher reported levels of pain (often a result of aging and chronic illnesses) are associated with greater alcohol and cannabis use (Brennan & Soohoo, 2013; Tsao, Stein, Ostrow, Stall, & Plankey, 2011); however, more research is needed to elucidate causal effects and potential coping mechanisms in these relationships. Measuring real-time alcohol and cannabis use patterns and predictors among older adults is critical to better understanding substance use in this population.

Previous work by our group has demonstrated that smartphone-based EMA is highly feasible among older adults with and without HIV (Moore, Depp, Wetherell, & Lenze, 2016; Moore, Kaufmann, et al., 2016); however, it is additionally important to determine the validity of EMA in older populations. Furthermore, as previously mentioned existing studies have yet to use EMA to specifically examine substance use behaviors among older adults that cannot be measured in the laboratory or clinic. Thus, the aims of this study are to: 1) examine the convergent validity of smartphone-based EMA of substance use in relation to in-lab assessments in older adults; and 2) preliminarily examine real-time predictors of substance use (i.e., mood and pain). Our unique sample of older adults with and without HIV infection attempts to provide a real-world sample of individuals over 50 with varying health concerns. We predicted that EMA-reported alcohol and cannabis use will show convergent validity with well-validated laboratory assessments of alcohol and cannabis use, and lower levels of happiness and higher levels of anxious mood, depressed mood, and pain will predict greater subsequent likelihood of substance use.

2. Materials and Method

2.1 Participants

Twenty-two HIV-seropositive (HIV+) and 13 HIV-seronegative (HIV−) participants were recruited from the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Inclusion criteria were: 50 years of age or older, fluent in English, and ability to provide written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: serious mental illness, neurological disease (e.g., stroke), positive alcohol breathalyzer, or urine toxicology for illicit substances (other than cannabis) at baseline visit. Potential participants from existing HNRP studies were called and asked about participating. Participants with more recent HNRP study visits were recruited first so neuromedical and neurobehavioral assessments did not have to be repeated. Participants who were new to the HNRP were told about all ongoing studies, and were subsequently screened for studies of interest to them. The current sample represents the first 35 participants to accept the offer to participate in this study. The UCSD Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures prior to protocol implementation. All participants provided written informed consent and were compensated for their participation.

2.2 Procedure

Participants completed two in-person visits (baseline and follow- up) and 14 days of EMA assessments.

2.2.1 Baseline Visit

At the baseline visit, participants completed neuromedical and neurobehavioral assessments. HIV/HCV seropositivity was determined using an HIV/HCV antibody point-of-care rapid test (Miriad, MedMira, Nova Scotia, Canada) and confirmed with Western Blot. Substance use over the past 30 days was assessed using a well-validated, interviewer-administered timeline follow-back assessment (TLFB; (Sobell & Sobell, 1992), a gold-standard measure for retrospectively assessing detailed alcohol and drug use. A semi-structured interview was administered to determine DSM-IV criteria for current and past mood disorders and substance abuse/dependence (Composite International Diagnostic Interview, v2.1; World Health Organization, 1998).

Participants were provided a touch-screen Samsung smartphone with a 4G Android Operating System in order to ensure a standard platform for all participants and not bias enrollment against people who do not own smartphones. If participants had their own smartphone, they were asked to carry their personal phone and the study-provided phone for the duration of the study. Study staff provided a structured 20–30 minute individual training session for proper smartphone use and EMA survey completion. Participants were also given a Smartphone Operating Manual to take home. The mobile platform used an encrypted native application framework to ensure data could not be accessed if the device was lost or stolen.

2.2.2 Fourteen-Day EMA Study Period

Participants were cued to answer EMA surveys four times per day over 14 days, providing up to 56 data points per person. The schedule of EMA surveys was customized to each participant’s sleep-wake schedules and occurred at random intervals in the morning, midday, afternoon, and evening. If participants did not respond to the initial survey alert, they were provided reminder alerts every two minutes for 16 minutes, after which the survey for that time point was deactivated. Participants were paid $1 for each survey completed.

EMA surveys included questions related to substance use, mood, and pain. Substance use was assessed via one item: “Since the last alarm, have you taken or used any of the following substances? (check all that apply).” The provided list of substances included: alcohol, cannabis/marijuana, caffeine, tobacco, herbal supplements, weight-loss supplements, cocaine/crack, crystal/meth, ecstasy/molly, heroin, other street drug(s), prescription drugs not prescribed to me, and no substance/drug use. Depression, anxiety, and happiness were each assessed using single- items (e.g., “I feel depressed…”) given five possible response options (1=Not at all to 5=Very much). Pain was assessed with a single item: “What is your pain level right now?” (1=Minimal or no pain to 10=Severe pain).

2.2.3 Follow-Up Visit

After the 14-day EMA study period, participants completed a follow- up survey regarding their experience with the EMA protocol. Using a scale of 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Very much), participants were asked to rate their overall enjoyment of the EMA experience, how much the smartphone interfered with their activities, and whether they had difficulty operating the device or understanding the EMA questions.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

2.3.1 Convergent Validity

EMA self-reported alcohol and cannabis use was compared to laboratory-assessed, retrospective self-reported alcohol and cannabis use from the baseline TLFB. Alcohol and cannabis were evaluated separately using two sets of bivariate linear regressions. We correlated the proportion of EMA surveys on which a participant endorsed using that substance to the TLFB-reported: (1) total number of units used (alcohol=drinks; cannabis=grams) and (2) total days of use over the 30 days prior to the baseline visit.

2.3.2 Preliminary Real-Time Predictors of Substance Use

A subset of 15 participants (nine HIV+ and six HIV−) who used alcohol or cannabis more than once during the 14-day EMA period was selected to evaluate predictors (mood and pain) of use. Alcohol and cannabis use were combined into one substance use variable to create a better distribution of use. Separate mixed-effects logistic regressions were completed to evaluate whether mood (i.e., depressed, anxious, happy) and pain predicted current (within-survey associations) and lagged (whether responses on previous surveys predicted future survey responses) substance use based on time of day (i.e., four points per day). Random intercepts were specified for participants. Covariates included day (1–14) and HIV status. Time of day was set as a categorical variable with four levels (i.e., time periods 1–4) for all mixed-effects logistic regression models. All statistical analyses were completed using R software (R Core Team, 2015).

3. Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Based on laboratory-administered TLFB, on average participants used alcohol on 3.7 days (SD=7.9), had 8.9 drinks (SD=8.9), used cannabis on 4.7 days (SD=9.7), and had 2.0 grams of cannabis (SD=5.7) in the 30 days before the baseline assessment. Of those who used alcohol or cannabis more than once during the 14-day EMA study period (n=15), alcohol use was reported on four EMA surveys on average and cannabis use on 10 surveys on average.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N=35)

| Mean (SD), Median [IQR], or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (yrs) | 57.5 (6.1) |

| Education (yrs) | 14.1 (2.3) |

| Gender (Male) | 26 (74.2%) |

| Race/Ethnicity (White) | 24 (68.6%) |

| Psychiatric/Substance Use Characteristics | |

| Current Major Depressive Disorder | 4 (11.4%) |

| Lifetime Major Depressive Disorder | 19 (54.3%) |

| Current alcohol use disorder | 1 (0.03%) |

| Lifetime alcohol use disorder | 16 (45.7%) |

| Current cannabis use disorder | 2 (0.06%) |

| Lifetime cannabis use disorder | 13 (37.1%) |

| Days of alcohol use in 30 days prior to baseline1 | 3.7 (7.9, 0–30) |

| Drinks in 30 days prior to baseline1 | 8.9 (23.2, 0–120) |

| Days of cannabis use in 30 days prior to baseline1 | 4.7 (9.7, 0–30) |

| Grams of cannabis used in 30 days prior to baseline1 | 2.0 (5.7, 0–30) |

| Medical Characteristics | |

| HIV | 22 (62.9%) |

| Hepatitis C | 9 (25.7%) |

| HIV Disease Characteristics2 | |

| Est. duration of HIV infection (yrs) | 22.3 (8.0) |

| History of AIDS | 13 (59.1%) |

| Nadir CD4 (cells/μl) | 208 [47.5–310] |

| Current CD4 (cells/μl) | 706.5 [506.5–834.8] |

| Plasma viral load detectable (>50 copies/mL) | 0 (0.0%) |

| EMA-Reported Substance Use3 | |

| Surveys on which alcohol use was endorsed1 | 4.0 (5.1, 0–17) |

| Surveys on which cannabis use was endorsed1 | 10.5 (13.7, 0–48) |

Data represents: Mean (SD, range)

Based on the subset of participants with HIV infection (n=22).

Based on the subset of participants who endorsed alcohol or cannabis use on more than one survey over the 14-day EMA study period (n=15).

When comparing the subset of 15 alcohol- or cannabis-using participants to the other 20 participants in the sample, groups do not differ on any demographic, psychiatric, or medical characteristics at α=0.05. At trend-level (p<0.10), however, there were group differences in race/ethnicity, current major depressive disorder (MDD), and lifetime cannabis use disorder. Current substance users had a lower percentage of White participants (53.3% vs. 80.0%, p=0.09), a higher percentage of participants with current MDD (30.0% vs. 5.6%, p=0.08), and a higher percentage of participants with lifetime cannabis use disorder (53.3% vs. 25.0%, p=0.09).

Regarding EMA usage and adherence, participants completed an average of 89.5% of possible EMA surveys (M=49.4, SD=5.9, range=31–56). In the follow- up survey, participants reported an average of “somewhat enjoyed the experience of using the smartphone” (mean rating of 2.43; SD=1.45), and that the smartphone did not interfere with their daily activities (M=0.93, SD=0.87). They also reported minimal difficulty operating the smartphone (M=0.13, SD=0.43) or understanding EMA questions (M=0.10, SD=0.40).

3.2 Convergent Validity of EMA Self-Reported Alcohol and Cannabis Use

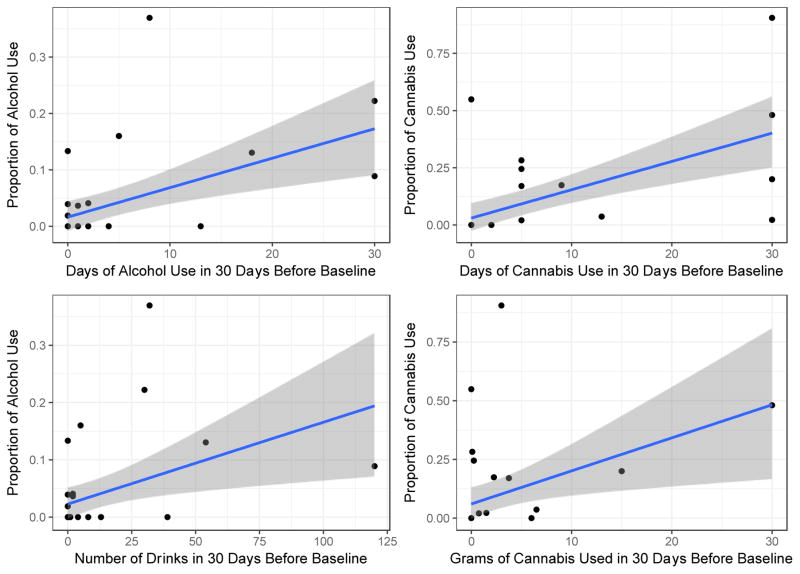

On the baseline TLFB, 14 participants (40.0%) reported drinking alcohol and 11 participants (31.4%) reported using cannabis. During the 14-day EMA study period, 10 participants (28.6%) reported drinking alcohol on more than one EMA survey and 11 participants (31.4%) reported using cannabis on more than one EMA survey. There were six participants who reported use on the TLFB and no use via EMA, and three who reported use via EMA and no use the TLFB. The proportion of EMA surveys on which participants endorsed using alcohol was positively related to both the TLFB-reported number of drinking days (r=0.52, p=0.002) and total drinks consumed (r=0.42, p=0.013). The proportion of EMA surveys on which participants endorsed using cannabis was also positively related to both the TLFB-reported number of days of cannabis use (r=0.61, p<0.001) and total grams of cannabis used (r=0.41, p=0.016; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Associations between EMA self-reported substance use and retrospective self-reported substance use. Y-axes represent EMA self-reports and X-axes represent laboratory self-reports.

3.3 Preliminary Real-Time Predictors of Substance Use (N=15)

3.3.1 Time of day

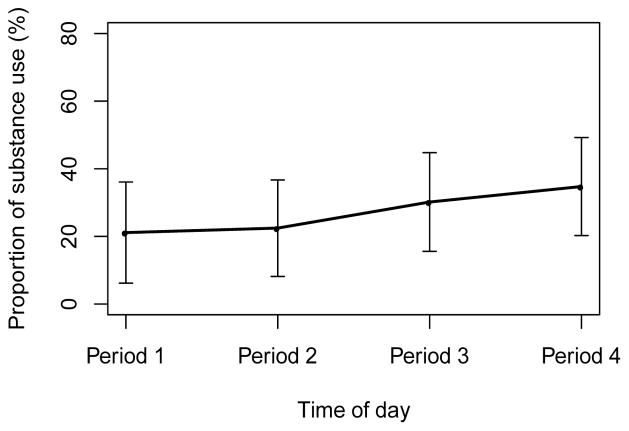

Results showed a significant effect of time of day on substance use (OR=1.42 per time period, 95% CI=1.193–1.694, p<0.001), such that there was a gradual linear increase in the log-odds of substance use over time in the course of the day (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Observed proportions of substance use by time of day. Error bar denotes 95% confidence interval for the mean. Time of day: four EMA surveys per day. Periods 1–4 refer to the morning, midday, afternoon, and evening in a day, respectively.

3.3.2 Mood

Participants reported low levels of depressed (M=1.30, SD=0.58 on the 1–5 scale) or anxious (M=1.26, SD=0.56 on the 1–5 scale) mood. The distribution of responses for depressed mood and anxious mood were positively skewed, with only 26.1% and 20.5% of responses >1 for depressed and anxious mood, respectively. Participants’ ratings of happiness were approximately normally distributed (M=3.27, SD=1.27).

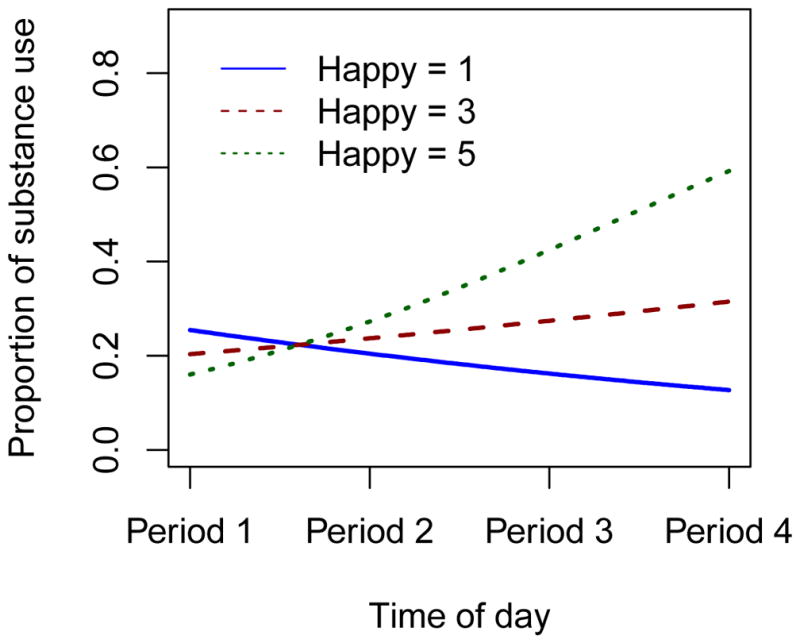

Table 2 displays results for all mixed-effects logistic regression models. There were no current or lagged effects of depressed mood on substance use (p’s>0.05). There was also no current effect of anxious mood on substance use (p>0.05); however, we found a significant lagged effect of anxious mood on subsequent substance use (OR=1.737, 95% CI=0.960–2.103, p=0.023), such that higher anxiety ratings were associated with greater odds of substance use on the next EMA survey. When examining the current effect of happiness on substance use, results showed a notable interaction effect of happiness and time of day (Ratio of OR=1.383 per unit of happiness and time period, 95% CI=1.184–1.617, p<0.001), such that as happiness increases, the relationship between substance use and time of day becomes more positive (Figure 3). No lagged effect of happiness on substance use was found.

Table 2.

Mixed-effects logistic regression models for current and lagged effects of mood on substance use. Models include subject-specific random effects (“random intercepts”).

| Variable | OR | CI (95%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| aModel for current effect of depressed mood on substance use | |||

| Current depressed mood (per unit) | 0.914 | [0.615–1.358] | 0.650 |

| Time period | 1.423 | [1.194–1.697] | <0.001 |

| Day | 0.987 | [0.941–1.036] | 0.610 |

| HIV status (ref. HIV−) | 0.301 | [0.073–1.245] | 0.097 |

| aModel for lagged effect of depressed mood on substance use | |||

| Lagged depressed mood (per unit) | 1.232 | [0.770–1.971] | 0.380 |

| Time period | 1.452 | [1.086–1.940] | 0.012 |

| Day | 0.986 | [0.929–1.046] | 0.630 |

| HIV status (ref. HIV−) | 0.287 | [0.067–1.233] | 0.093 |

| aModel for current effect of anxious mood on substance use | |||

| Current anxious mood (per unit) | 1.421 | [0.960–2.103] | 0.079 |

| Time period | 1.438 | [1.205–1.715] | <0.001 |

| Day | 0.987 | [0.941–1.036] | 0.60 |

| HIV status (ref. HIV−) | 0.320 | [0.085–1.202] | 0.092 |

| bModel for lagged effect of anxious mood on substance use | |||

| Lagged anxious mood (per unit) | 1.737 | [1.080–2.792] | 0.023 |

| Time period | 1.493 | [1.114–2.001] | 0.007 |

| Day | 0.985 | [0.928–1.046] | 0.620 |

| HIV status (ref. HIV−) | 0.276 | [0.069–1.104] | 0.069 |

| bModel for current effect of happiness on substance use | |||

| Current happiness (per unit) | 0.817 | [0.569–1.172] | 0.270 |

| Time period | 0.492 | [0.290–0.836] | 0.009 |

| Day | 0.990 | [0.942–1.040] | 0.680 |

| HIV status (ref. HIV−) | 0.306 | [0.066–1.420] | 0.069 |

| Happiness x Time period | 1.383 | [1.184–1.617] | <0.001 |

| aModel for lagged effect of happiness on substance use | |||

| Current happiness (per unit) | 1.057 | [0.795–1.406] | 0.700 |

| Time period | 1.438 | [1.076–1.921] | 0.360 |

| Day | 0.987 | [0.931–1.048] | 0.680 |

| HIV status (ref. HIV−) | 0.268 | [0.062–1.148] | 0.076 |

Notes: Current effect = effect on substance use within same EMA survey; Lagged effect = effect on substance use on the next EMA survey; Time = four periods per day, linear effect on log-odds of substance use. Effect is per one period.

Model with non-significant predictor variables of interest

Model with significant predictor variables of interest

Figure 3.

The predicted proportion of substance use by time of day based on happiness rating. The figure shows that the higher happiness is associated with a greater increase of use throughout the day.

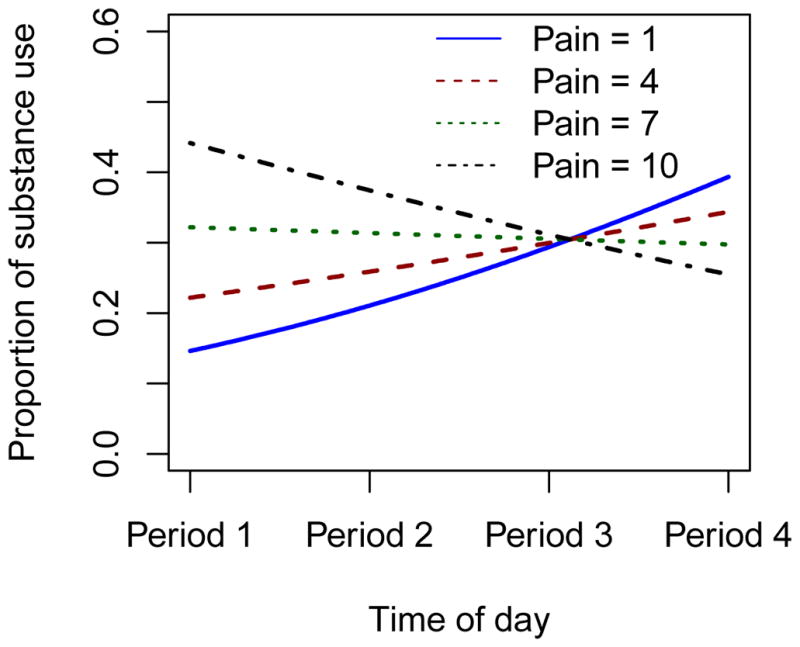

3.3.3 Pain

Pain ratings were positively skewed with a mean of 2.82 and standard deviation of 2.34 on the 1–10 scale. Results showed a significant interaction effect of current pain and time of day on substance use (Ratio of OR=0.901 per unit of pain and time period, 95% CI=0.836–0.970, p=0.005; Table 3). Figure 4 shows that higher pain levels are associated with a higher odds of substance use in the morning that stay constant or decrease throughout the day, whereas lower pain levels are associated with lower odds of substance use in the morning that increase throughout the day. There was no lagged effect of pain on substance use.

Table 3.

Mixed-effects logistic regression models for the current and lagged effects of pain levels on substance use. Models include subject-specific random effects (“random intercepts”).

| Variable | OR | CI (95%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| aModel for current effect of pain level on substance use | |||

| Current pain level (per unit) | 1.255 | [1.058–1.489] | 0.009 |

| Time period | 1.982 | [1.467–2.677] | <0.001 |

| Day | 0.985 | [0.938–1.034] | 0.530 |

| HIV status (ref. HIV−) | 0.303 | [0.074–1.242] | 0.097 |

| Pain level x Time period | 0.901 | [0.836–0.970] | 0.005 |

| bModel for lagged effect of pain level on substance use | |||

| Lagged pain level (per unit) | 1.146 | [0.845–1.554] | 0.380 |

| Time period | 1.866 | [1.158–3.009] | 0.010 |

| Day | 0.989 | [0.932–1.050] | 0.720 |

| HIV status (ref. HIV−) | 0.267 | [0.060–1.180] | 0.081 |

| Pain level x Time period | 0.921 | [0.816–1.041] | 0.190 |

Notes: Current effect = effect on substance use within same EMA survey; Lagged effect = effect on substance use on the next EMA survey; Time = four periods per day, linear effect on log-odds of substance use. Effect is per one period.

Model with significant predictor variables of interest

Model with non-significant predictor variables of interest

Figure 4.

The predicted proportion of substance use by time of day based on pain levels. The figure shows that higher pain levels are associated with a higher odds of substance use in the morning that stay constant or decrease throughout the day, whereas lower pain levels are associated with lower odds of substance use in the morning that increase throughout the day.

4. Discussion

Prior work indicates that EMA is a highly accessible, feasible, tolerable, and valid method for assessing substance use across many clinical and non-clinical populations (Freedman, Lester, McNamara, Milby, & Schumacher, 2006; Shiffman, 2009; Yang et al., 2015). Our findings replicate feasibility and support the validity of smartphone-based EMA for measuring substance use in older adults with and without HIV infection. Results also suggest that future research may benefit from using this method to further characterize and examine real-time patterns, predictors, and consequences of substance use in this population. Because previous findings on effects of sustained light-to- moderate substance use on cognitive and physical health among older adults are mixed (Dinitto & Choi, 2011; Dowling et al., 2008; Moussa et al., 2014), use of EMA may help elucidate differential short- and long-term outcomes among individuals with different patterns and reasons for use.

Among the 15 participants who endorsed substance use over the 2-week EMA period, our preliminary findings indicated these participants were more likely to be non-White, have current Major Depressive Disorder, and have lifetime cannabis use disorder compared to participants who did not endorse substance use during the EMA period. These findings are consistent with previous studies examining disparities in substance use across race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (Buka, 2002), as well as those linking depression and substance use (Conner, Pinquart, & Gamble, 2009). In terms of convergent validity, results showed that the proportion of EMA surveys on which participants endorsed alcohol and cannabis use were significantly positively related to frequency and quantity of alcohol and cannabis use at baseline. Because the timeline follow-back (TLFB) assessed use on days prior to initiation of EMA surveys over a longer period (30 days vs. 10 days), we did not expect perfect correlations. We might expect stronger correlations if the retrospective self-report of substance use was completed immediately after the EMA study period; however, our current methods allow us to examine a broader summary of substance use patterns. Post-study feedback indicated high levels of acceptability of the EMA protocol, further supporting the use of smartphone-based EMA for substance use in this population.

In the subset of 15 participants who reported alcohol or cannabis use on more than one EMA survey, we found no current or lagged effects of depressed mood on substance use. There are several possible explanations for this null finding. First, small sample size may be limiting our power to detect an effect. Second, depressed mood ratings were lacking variability, as almost 75% of responses were “not at all” depressed. Lastly, although we found an association between current Major Depressive Disorder and substance use, real-time data also captures instances when participants likely used substances for a wide variety of reasons beyond coping with negative emotions, such as social context, taste, pleasure, or enjoyment (Cooper, Kuntsche, Levitt, Barber, & Wolf, 2016; Mohr et al., 2001). This highlights the complexity and importance of using real-time, real-world data to accompany laboratory assessments for a more comprehensive view of mood-substance use relationships.

There was also no association between concurrent anxious mood and substance use; however, there was a significant lagged effect of anxious mood such that greater anxious mood predicted greater likelihood of substance use on the next EMA survey. This finding is consistent with prior EMA research showing higher anxiety predicts subsequent alcohol and cannabis use (Buckner, Crosby, Silgado, Wonderlich, & Schmidt, 2012; Simons, Dvorak, Batien, & Wray, 2010), as well as research showing that older adults report using substances to cope with stress (Mauro et al., 2015). We notably found these effects in a sub-clinical sample with mild-to-moderate substance use, highlighting the need for future research to evaluate EMA for substance use in a higher risk sample of older adults with substance use disorders.

Additionally, we found notable interaction effects of happiness and time on substance use, as well as pain and time on substance use. Results showed that individuals were more likely to use later in the day, and this later-day use was associated with increased levels of happiness. When an individual experienced pain, however, they were more likely to begin use earlier in the day, potentially to manage their pain such as with cannabis, which is an increasingly common, prescribed treatment for pain, especially among HIV+ adults (Ellis et al., 2009). These preliminary results warrant future research on older individuals with clinical levels of pain in order to understand whether substances are being used in compliance with prescribed medical treatment. Lastly, we did not find any HIV effects. Although these results are preliminary and lack power, the non-significant differences between HIV+ and HIV− participants may represent a survival bias, such that older HIV+ adults in our study may be living healthier lives than other HIV+ individuals who have not lived beyond 50 years of age.

The current study adds to the literature by confirming the validity of EMA for substance use in a real-world sample of older adults who have varying psychiatric and medical illnesses. However, this study also has some limitations. First, our initial sample was relatively small, limiting generalizability and detection of significant findings. In subsequent analyses, we further reduced sample size to include only participants who reported substance use over the EMA period. The small proportion of substance using older adults in our sample reflects study recruitment. That is, because data from this study were collected as part of a larger study with the aim to examine everyday functioning in older adults, participants were not screened for their use of substances upon recruitment. Nonetheless, the likelihood of getting 15 substance users out of 35 older adults is relatively consistent with reports of prevalence of alcohol and marijuana use in this population (Blazer & Wu, 2009). Second, our EMA item assessing substance use does not attempt to measure quantity of use. Our results, however, provide support for future research to examine convergent validity of EMA-reported quantity of alcohol and cannabis use in older adults with and without HIV infection. Third, we did not collect any information about cannabis route of administration, or whether cannabis use was recreational, prescribed (and if so, for what reason), or both. These would be important to consider in future EMA studies examining predictors, as these factors would likely moderate mood-use and pain-use associations.

4.1 Conclusions

Overall, the current study provides evidence to support the use of smartphone-based EMA to assess alcohol and cannabis use in older adults with and without HIV-infection. Although our preliminary findings of mood and pain predictors of substance use warrant further study, they point towards the importance of using EMA to measure substance use in older adult populations with anxiety, pain, and substance use. EMA is a valid measurement method in this population whose patterns, predictors, and consequences of substance use are greatly understudied. The current study findings support continued validation of EMA-reported substance use in older adult populations, and suggest that further research is needed in older adults with varying levels of substance use.

Highlights.

Ecological momentary assessment of substance use shows validity in older adults.

Greater anxiety predicts subsequent substance use.

Greater happiness predicts substance use in the evening/at night.

Higher pain level predicts substance use in the morning.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grant K23-MH107260 (RCM), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grant T32-AA013525 (EWP), and National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant T32-DA031098 (LCO). NIMH, NIAAA, and NIDA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program group is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, the Naval Hospital, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, and includes: Director: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D., Co-Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Associate Directors: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and Scott Letendre, M.D.; Center Manager: Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Melanie Sherman; Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), Scott Letendre, M.D., J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., Brookie Best, Pharm.D., Rachel Schrier, Ph.D., Terry Alexander, R.N., Debra Rosario, M.P.H.; Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Steven Paul Woods, Psy.D., Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D., Mariana Cherner, Ph.D., David J. Moore, Ph.D., Matthew Dawson; Neuroimaging Component: Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D. (P.I.), Terry Jernigan, Ph.D., Monte S. Buchsbaum, M.D., John Hesselink, M.D., Sarah L. Archibald, M.A., Gregory Brown, Ph.D., Richard Buxton, Ph.D., Anders Dale, Ph.D., Thomas Liu, Ph.D.; Neurobiology Component: Eliezer Masliah, M.D. (P.I.), Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D., Ian Everall, FRCPsych., FRCPath., Ph.D.; Neurovirology Component: David M. Smith, M.D. (P.I.), Douglas Richman, M.D.; International Component: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., (P.I.), Mariana Cherner, Ph.D.; Developmental Component: Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; (P.I.), Stuart Lipton, M.D., Ph.D.; Participant Accrual and Retention Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (P.I.), Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Data Management and Information Systems Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (P.I.), Clint Cushman; Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Florin Vaida, Ph.D. (Co-PI), Reena Deutsch, Ph.D., Anya Umlauf, M.S., Christi Kao, M.S.

Footnotes

Contributors

Author RCM designed the study and wrote the protocol. Author BT conducted the statistical analyses with consultation and contributions from FV. Authors EWP and LCO wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with revisions and contributions from all authors including BT, CAD, FV, DJM, and RCM. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Blazer DG, Wu LT. The epidemiology of substance use and disorders among middle aged and elderly community adults: national survey on drug use and health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(3):237–245. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318190b8ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PL, Soohoo S. Pain and use of alcohol in later life: prospective evidence from the health and retirement study. J Aging Health. 2013;25(4):656–677. doi: 10.1177/0898264313484058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Crosby RD, Silgado J, Wonderlich SA, Schmidt NB. Immediate antecedents of marijuana use: an analysis from ecological momentary assessment. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2012;43(1):647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buka SL. Disparities in health status and substance use: ethnicity and socioeconomic factors. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S118–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol Aging. 2006;21(1):140–151. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Pinquart M, Gamble SA. Meta-analysis of depression and substance use among individuals with alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37(2):127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A, Barber LL, Wolf S. Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco. The Oxford handbook of substance use and substance use disorders. 2016;1:1–117. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(1):31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Grant BF. Changes in alcohol consumption: United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinitto DM, Choi NG. Marijuana use among older adults in the U.S.A.: user characteristics, patterns of use, and implications for intervention. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(5):732–741. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210002176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling GJ, Weiss SR, Condon TP. Drugs of abuse and the aging brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(2):209–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Toperoff W, Vaida F, van den Brande G, Gonzales J, Gouaux B, … Atkinson JH. Smoked medicinal cannabis for neuropathic pain in HIV: a randomized, crossover clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(3):672–680. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman MJ, Lester KM, McNamara C, Milby JB, Schumacher JE. Cell phones for ecological momentary assessment with cocaine-addicted homeless patients in treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30(2):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaremka LM, Andridge RR, Fagundes CP, Alfano CM, Povoski SP, Lipari AM, … Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Pain, depression, and fatigue: loneliness as a longitudinal risk factor. Health Psychol. 2014;33(9):948–957. doi: 10.1037/a0034012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Lin EH, Kroenke K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy GJ, Efremova I, Frazier A, Saba A. The emerging problems of alcohol and substance abuse in late life. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless. 1999;8(4):227–239. doi: 10.1023/A:1021392004501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbis A, Sacco P, Blazer DG, Moore AA. Substance abuse among older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(3):629–654. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannes ZL, Burrell LE, Bryant VE, Dunne EM, Hearn LE, Whitehead NE. Loneliness and substance use: the influence of gender among HIV+ Black/African American adults 50+ AIDS Care. 2016;28(5):598–602. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1120269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M, Lipari RN, Hays C, Van Horn SL. The CBHSQ Report. Rockville (MD): 2013. A Day in the Life of Older Adults: Substance Use Facts. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro PM, Canham SL, Martins SS, Spira AP. Substance-use coping and self-rated health among US middle-aged and older adults. Addict Behav. 2015;42:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Carney MA, Affleck G, Hromi A. Daily interpersonal experiences, context, and alcohol consumption: crying in your beer and toasting good times. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80(3):489–500. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AA, Whiteman EJ, Ward KT. Risks of combined alcohol/medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(1):64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Depp CA, Wetherell JL, Lenze EJ. Ecological momentary assessment versus standard assessment instruments for measuring mindfulness, depressed mood, and anxiety among older adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;75:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Kaufmann CN, Rooney AS, Moore DJ, Eyler LT, Granholm EL, … Depp CA. Feasibility and acceptability of ecological momentary assessment of daily functioning among older adults with HIV. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, IN PRESS. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussa MN, Simpson SL, Mayhugh RE, Grata ME, Burdette JH, Porrino LJ, Laurienti PJ. Long-term moderate alcohol consumption does not exacerbate age-related cognitive decline in healthy, community-dwelling older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:341. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Starks TJ, Millar BM, Boonrai K, Marcotte D. Patterns of substance use among HIV-positive adults over 50: implications for treatment and medication adherence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;139:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce RS, Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML, Mudar P. A longitudinal model of social contact, social support, depression, and alcohol use. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1):28–38. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2001;23(4):245–266. doi: 10.1207/S15324834basp2304_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.r-project.org/

- Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35:75–83. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxs009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychol Assess. 2009;21(4):486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Batien BD, Wray TB. Event-level associations between affect, alcohol intoxication, and acute dependence symptoms: Effects of urgency, self-control, and drinking experience. Addict Behav. 2010;35(12):1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Measuring alcohol consumption. Springer; 1992. Timeline follow-back; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drud Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tsao JC, Stein JA, Ostrow D, Stall RD, Plankey MW. The mediating role of pain in substance use and depressive symptoms among Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) participants. Pain. 2011;152(12):2757–2764. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Composite Diagnositic International Interview (CIDI, version 2.1) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Linas B, Kirk G, Bollinger R, Chang L, Chander G, … Latkin C. Feasibility and Acceptability of Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment of Alcohol Use Among African American Men Who Have Sex With Men in Baltimore. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(2):e67. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]