Abstract

Background

Caregiver burden is a serious concern for family caregivers of dementia patients, but its nature is unclear in patients with semantic dementia (SD). This study aimed to clarify caregiver burden for right- (R > L) and left-sided (L > R) predominant SD versus behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) patients.

Methods

Using the Japanese version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, we examined caregiver burden and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in 43 first-visit outpatient/family caregiver dyads (bvFTD, 20 dyads; SD [L > R], 13 dyads; SD [R > L], 10 dyads).

Results

We found a significant difference in ZBI score between the 3 diagnostic groups. Post hoc tests revealed a significantly higher ZBI score in the bvFTD than in the SD (L > R) group. The ZBI scores in the SD (L > R) and SD (R > L) groups were not significantly different, although the effect size was large. Caregiver burden was significantly correlated with BPSD scores in all groups and was correlated with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living decline in the bvFTD and SD (R > L) groups.

Conclusion

Caregiver burden was highest in the bvFTD group, comparatively high in the SD (R > L) group, and lowest in the SD (L > R) group. Adequate support and intervention for caregivers should be tailored to differences in caregiver burden between these patient groups.

Keywords: Frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, Zarit Burden Interview, Family caregivers

Introduction

Caregiver burden among family caregivers of dementia patients is a serious concern. Caregiver burden is known to increase when caring for patients with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), cognitive dysfunction, low activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental ADL (IADL) scores, and other problems that arise from dementia [1, 2].

Compared with noncaregivers, caregivers have higher rates of depressive and anxiety disorders [3, 4, 5], a lower quality of life [6, 7], a higher risk of hypertension and heart disease, decreased immunity, and greater mortality [8]. Caregiver burden is consistently reported to be higher for caregivers who work with patients with behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) than for those working with patients with other forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer disease [9, 10, 11]. This may be because patients with bvFTD often develop the condition at an early age and quickly begin to exhibit changes in personality, interpersonal relationships, and behavior.

In contrast, caregiver burden in individuals who care for patients with semantic dementia (SD) is generally low [12], although few studies have examined this topic. SD, along with bvFTD and progressive nonfluent aphasia, is a subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), which is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by selective loss of semantic memory associated with focal atrophy of the anterior temporal lobes. SD is associated with asymmetrical atrophy of the anterior temporal lobe [13], and patients with right- and left-sided predominant SD present with a number of distinct symptoms. In particular, individuals with right-sided predominant SD (R > L) exhibit prosopagnosia and behavioral change, whereas those with left-sided predominant SD (L > R) exhibit severe language disturbance (e.g., word-finding difficulties or poor comprehension) [13, 14].

It is possible that caregiver burden in SD (R > L) is relatively high compared to that in SD (L > R) because of behavioral problems similar to those in bvFTD. However, previous studies that focused on caregiver burden for patients with SD have not distinguished between patients with right- and left-sided predominant cerebral atrophy. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine caregiver burden for SD patients with right- and left-sided predominant atrophy and bvFTD patients, and to identify characteristics of caregiver burden and related factors among these subtypes of FTLD.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Human Ethics Review Committee of Kumamoto University. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and their primary caregivers, who were family members. Participants in this study were first-visit outpatients at the Dementia Clinic of the Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kumamoto University Hospital, who were recruited at the clinic between April 2007 and April 2016. Participants were diagnosed with bvFTD and SD according to the international consensus criteria for probable bvFTD [15] and the consensus criteria for the clinical diagnosis of FTLD [16], respectively.

Patients who fulfilled the above criteria (n = 43) were examined by senior neuropsychiatrists (M.H. and M.I.) who have sufficient experience with dementia patients. All patients underwent routine laboratory tests, neuroimaging studies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and standard neuropsychological examinations. For SD diagnoses, 23 patients were classified into 2 subgroups, namely left- or right-sided dominant cases, based on the predominance of temporal lobe atrophy observed on MRI and the predominance of temporal lobe cerebral blood flow hypoperfusion on SPECT. Left-handed and ambidextrous patients with SD were excluded by the Edinburgh Inventory [17]. As a result, we recruited a total of 43 patient/family caregiver dyads (bvFTD, 20 dyads; SD [L > R], 13 dyads; SD [R > L], 10 dyads) (Fig. 1).

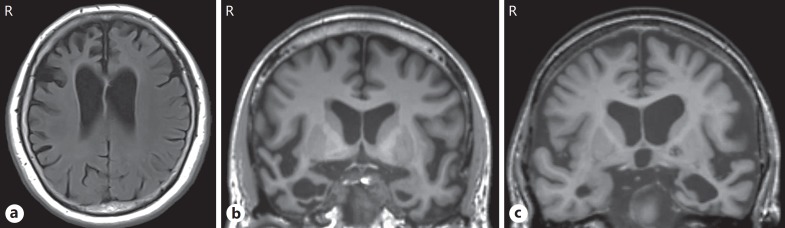

Fig. 1.

Cases of bvFTD, SD (R > L), and SD (L > R). a Representative bvFTD case. A 65-year-old housewife presented with an 8-year history of progressive alterations in her personality and behaviors, such as stereotypy and apathy, and word-finding difficulty. Her MRI revealed circumscribed right-sided dominant frontal lobar atrophy. b Representative SD (R > L) case. A 60-year-old professional man presented with a 2-year history of prosopagnosia, clock-watching or adherence to a strict daily timetable, and increased psychological symptoms, such as apathy and depression. He also showed impairments in word comprehension and naming. His MRI revealed circumscribed bilateral temporal atrophy, which was more marked on the right side. c Representative SD (L > R) case. A 75-year-old female farmer presented with a 3-year history of progressive difficulty in understanding speech and in naming with semantic paraphasia. A strictly fixed daily rhythm that looks like a timetable and psychological symptoms, such as irritability and apathy, were gradually apparent. Her MRI revealed circumscribed bilateral temporal atrophy, which was more marked on the left side. bvFTD, behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia; SD, semantic dementia; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Measures

We used the Japanese version of the Zarit Burden Interview (J-ZBI) to measure caregiver burden [18, 19]. The J-ZBI consists of 22 items concerning the impact of patient disabilities on the lifestyle of the caregiver. These items address caregiver health, psychological well-being, finances, social life, and the relationship between the caregiver and recipient of care. Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. The sum of the scores ranges from 0 to 88, and a higher score indicates a higher burden.

We assessed cognitive function using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [20] and dementia severity using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [21], which characterizes 6 domains of cognitive and functional performance. The overall CDR score can then be used to classify cognitive function into 1 of 5 levels: no dementia, CDR = 0; questionable demen tia, CDR = 0.5; mild dementia, CDR = 1; moderate dementia, CDR = 2; or severe dementia, CDR = 3.

ADL and IADL were assessed using the Physical Self-Maintenance Scale (PSMS) and a part of the Lawton IADL scale, respectively [22, 23]. Using the PSMS, 6 domains (i.e., toileting, feeding, dressing, grooming, physical ambulation, and bathing) were assessed, and the scores ranged from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating better functioning. Using the Lawton IADL scale, 5 domains out of 8 (i.e., using the telephone, shopping, using transportation, handling medications, and handling finances) were assessed. Three domains (i.e., preparing food, housekeeping, and doing laundry) were excluded from the analysis because of gender differences, that is, women do more housework than men in Japan. The scores range from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating better functioning.

We used the Japanese version of the 10-item Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [24, 25] to assess BPSD. This inventory covers the following 10 domains: hallucinations, delusions, agitation/aggression, depression, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability/lability, and aberrant motor behavior. The score of each domain is calculated by frequency (1 = less than once per week; 2 = once per week; 3 = a few times per week; 4 = once or more per day) × severity (1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe), and the sum of all scores in each domain represents the NPI total score (range 0–120).

Statistical Analysis

First, we compared the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of bvFTD, SD (L > R), and SD (R > L) patients using a χ2 test and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey post hoc test. Second, we compared the caregiver burden (ZBI total score) between the patient groups using a one-way ANOVA. Third, we calculated the mean ZBI scores of each CDR severity group in 3 diagnostic groups. Finally, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between caregiver burden and patient sociodemographic and clinical features. As efficacy measures, we calculated the Cohen η2 and d. The magnitude of the effect size was set such that η2 = 0.01 (small), η2 = 0.06 (medium), and η2 = 0.14 (large), and d = 0.2 (small), d = 0.5 (medium), and d = 0.8 (large).

Results

The participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. We found no significant differences between the 3 diagnostic groups in terms of age, gender, education, duration of illness, NPI score, and CDR severity. However, we observed a significant difference in MMSE scores between the 3 diagnostic groups (F = 3.66, p = 0.035, η2 = 0.16), and a post hoc test showed significantly lower scores for the SD (L > R) group compared to the SD (R > L) group (15.3 vs. 22.8, p < 0.01, d = 1.28). We expect that this is simply a result of heightened semantic dysfunction in SD (L > R) patients. There were significant differences between the PSMS and Lawton IADL scores in the 3 diagnostic groups, and a post hoc test showed significantly lower scores for the bvFTD group than for the SD (L > R) and SD (R > L) groups. Among the caregivers, 27 (62.8%) were spouses and 31 (72.1%) were female. We found no significant differences between the 3 diagnostic groups in terms of relationship to patients or gender of caregivers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 3 diagnostic groups

| bvFTH (n = 20) | SD (L > R) (n = 13) | SD (R > L) (n = 10) | F/χ2a | P | Effect size (η2) | Bonferroni post hoc test | Effect size (d) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | ||||||||

| Age, years | 66.3±9.9 | 71.2±6.9 | 66.4±6.8 | 1.51 | 0.234 | |||

| Sex, n | ||||||||

| Male/female | 10/10 | 4/9 | 6/4 | 2.12 | 0.346 | |||

| Education, years | 11.7±2.5 | 10.6±2.4 | 12.4+4.2 | 1.10 | 0.343 | |||

| Duration of illness, years | 2.8±2.2 | 2.8±3.3 | 2.6±1.7 | 0.03 | 0.970 | |||

| MMSE score | 18.5±7.3 | 15.3±6.4 | 22.8±5.1 | 3.66 | 0.035 | 0.16 | bvFTD, SD (L > R); p = 0.564 | 0.45 (small) |

| (large) | SD (R > L), bvFTD; p = 0.288 | 0.65 (medium) | ||||||

| SD (R > L) > SD (L > R); p = 0.030 | 1.28 (large) | |||||||

| PSMS score | 3.8±2.2 | 5.3±1.5 | 5.4±0.8 | 3.94 | 0.027 | 0.17 | bvFTD < SD (L > R); p = 0.061 | 0.76 (medium) |

| (large) | bvFTD < SD (R > L); p = 0.069 | 0.84 (large) | ||||||

| SD (R > L), SD (L > R); p = 0.992 | 0.07 (small) | |||||||

| Lawton IADL scoreb | 2.9±1.9 | 4.5±0.8 | 4.4±1.1 | 5.9 | 0.006 | 0.23 | bvFTD < SD (L > R); p = 0.013 | 1.00 (large) |

| (large) | bvFTD < SD (R > L); p = 0.030 | 0.90 (large) | ||||||

| SD (R > L), SD (L > R); p = 0.994 | 0.07 (small) | |||||||

| NPI score | 17.2±11.6 | 11.5±11.1 | 16.9±14.6 | 0.97 | 0.387 | |||

| CDR severity, n 0/0.5/1/2/3 | 0/7/5/5/3 | 1/5/6/1/0 | 0/5/4/1/0 | 7.78 | 0.456 | |||

| Caregivers | ||||||||

| Relationship to patient, n Spouse/adult-child/other | 14/6/0 | 6/6/1 | 7/3/0 | 3.8 | 0.433 | |||

| Sex, n Male/female | 5/15 | 4/9 | 3/7 | 0.159 | 0.924 | |||

Values are means ± standard deviations unless otherwise indicated. ANOVA was used for continuous data and χ2 test for categorical data. bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; SD, semantic dementia; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; PSMS, Physical Self-Maintenance Scale; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating.

Test statistics.

Out of 5 points.

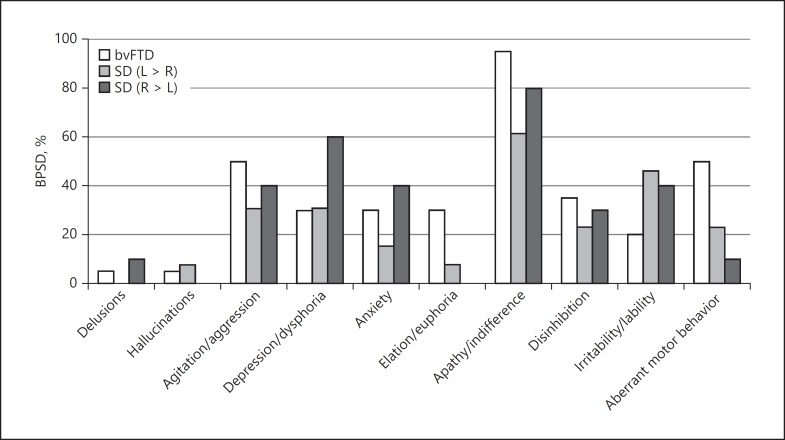

The prevalence of BPSD, as assessed by NPI, is shown in Figure 2. We found no significant differences for any symptoms between the 3 diagnostic groups. Apathy/indifference was present in more than half of the patients in every group and was especially high in the bvFTD group (95.0%). We found agitation and aberrant motor behavior in more than half of the patients in the bvFTD group and depression/dysphoria in more than half of the patients in the SD (R > L) group.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of BPSD in the 3 diagnostic groups. BPSD, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia; bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; SD, semantic dementia.

We found significant differences in ZBI scores between the bvFTD, SD (L > R), and SD (R > L) groups (F = 7.1, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.26). A post hoc test revealed that the ZBI scores were significantly higher in the bvFTD group than in the SD (L > R) group (p = 0.002, d = 1.51). We found no significant differences in ZBI scores between the SD (L > R) and SD (R > L) groups (p = 0.166). However, the effect size was large (d = 0.89) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Caregiver burden (ZBI score)

| bvFTH (n = 20) | SD (L > R) (n = 13) | SD (R > L) (n = 10) | F | P | Effect size (η2) | Bonferroni post hoc test | Effect size (d) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZBI score | 34.0±16.9 | 12.7±7.7 | 25.8±20.7 | 7.1 | 0.002 | 0.26 | bvFTD > SD (L > R); p = 0.002 | 1.51 (large) |

| (large) | bvFTD, SD (R > L); p = 0.570 | 0.45 (small) | ||||||

| SD (R > L), SD (L > R); p = 0.166 | 0.89 (large) |

Values are means ± standard deviations. ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview; bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; SD, semantic dementia

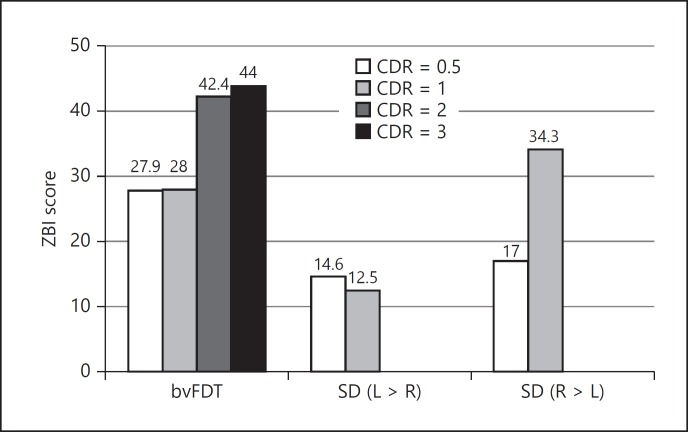

As an additional and preliminary analysis, we calculated the mean ZBI scores of each CDR severity group in 3 diagnostic groups only if the number of cases was > 2 in each severity group (Fig. 3). In the bvFTD group, the ZBI mean score of CDR = 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 was 27.9, 28.0, 42.4, and 44.0, respectively. In the SD (L > R) group, the mean score of CDR = 0.5 and 1 was 14.6 and 12.5, respectively. In the SD (R > L) group, the mean score of CDR = 0.5 and 1 was 17.0 and 34.3, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Caregiver burden (ZBI score) in each CDR severity. ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; SD, semantic dementia.

The correlation coefficients between ZBI scores and other factors are shown in Table 3. For all diagnostic groups, the ZBI score was not significantly correlated with patient age, duration of education, or duration of illness. The ZBI score was significantly correlated with the PSMS and Lawton IADL in the bvFTD group and with the Lawton IADL score in the SD (R > L) group. In all groups, the ZBI score was significantly correlated with the NPI score. Especially depression/dysphoria was significantly correlated with the ZBI score in the SD (L > R) group (r = 0.842, p < 0.001). Although the ZBI score was weakly correlated with the MMSE score in the 3 groups, the correlation was not significant.

Table 3.

Correlation with ZBI (Pearson r)

| bvFTH (n = 20) | SD (L > R) (n = 13) | SD (R > L) (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.091 | −0.219 | 0.511 |

| Education | −0.092 | 0.305 | −0.060 |

| Duration of illness | 0.036 | 0.154 | 0.254 |

| MMSE score | −0.418† | −0.405 | −0.621† |

| PSMS score | −0.563* | −0.110 | −0.594† |

| Lawton IADL score (out of 5 points) | −0.519* | −0.342 | −0.834* |

| NPI score (subscale) | 0.748** | 0.790** | 0.818** |

| Delusions | - | - | - |

| Hallucinations | - | - | - |

| Agitation/aggression | 0.602 | 0.432 | 0.530 |

| Depression/dysphoria | 0.367 | 0.842** | −0.007 |

| Anxiety | 0.246 | - | 0.592 |

| Elation/euphoria | 0.352 | - | - |

| Apathy/indifference | 0.531 | 0.379 | 0.668 |

| Disinhibition | 0.449 | 0.144 | 0.476 |

| Irritability/lability | 0.156 | 0.394 | 0.655 |

| Aberrant motor behavior | 0.295 | 0.267 | - |

ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview; bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; SD, semantic dementia; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; PSMS, Physical Self-Maintenance Scale; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; -, excluded from analysis because <3 patients had symptoms.

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.1; Bonferroni correction was conducted for each NPI subscale.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the differences in caregiver burden and related factors between patients with bvFTD, SD (L > R), and SD (R > L). Our results were consistent with those of previous studies that found a high caregiver burden for patients with bvFTD [9, 10] even after taking into consideration the severity of the disease. These studies reported various behavioral disturbances in patients with bvFTD, the most troubling of which included personality changes and lack of empathy. Indeed, these symptoms most strongly aggravated the mental health of caregivers [11, 26]. To date, information about caregiver burden for patients with SD is scarce. A study by Uflacker et al. [12] showed that, compared to bvFTD, SD was associated with a lower caregiver burden. Actually, caregivers of patients with SD (L > R) felt a lower burden. However, we found a comparatively high burden among caregivers of patients with SD (R > L). A study conducted by Thompson et al. [13] revealed that patients with SD (R > L) were more frequently impaired than those with SD (L > R) in terms of social awkwardness, job loss, loss of insight, and difficulty with person identification. These characteristics of SD (R > L), which sometimes lead to diagnostic confusion with bvFTD in the early stages of illness [13], might increase caregiver burden to a level comparable with that for patients with bvFTD. As for SD (L > R), the main symptoms are associated with language disturbance, and the behavioral symptoms are not prominent in the early stages of illness. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that caregiver burden for these patients would be lower than that for patients with SD (R > L) and bvFTD.

However, the participants in this study were first-visit outpatients, i.e., many of them were in the early stages of disease. The caregiver burden of patients with SD (L > R) likely increases as the frontal and temporal symptoms of the disease gradually emerge [14]. Thus, longitudinal changes in caregiver burden represent a valuable topic for future studies.

In addition to differences in the level of caregiver burden, we found that different factors were related to the caregiver burden in the different subgroups of FTD. Specifically, caregivers of patients with bvFTD felt a higher burden when impaired ADL and IADL, and some BPSD symptoms, such as agitation, apathy, and disinhibition, were prominent in their patients. In our study, we found greater impairment of ADL and IADL in patients with bvFTD, which was consistent with previous studies [27]. ADL and IADL would be one of the most important related factors in terms of caregiver burden in bvFTD.

Caregiver burden was equally strongly correlated with BPSD in the 3 diagnostic groups, which is consistent with a previous study targeted at patients with FTD [28]. In the SD (L > R) group, patient levels of depression were significantly correlated with caregiver burden. Many patients with SD (L > R) have insight regarding their language disturbance [13], leading to increased patient levels of depression and subsequent emotional burden for their caregivers. In contrast, patient levels of depression were not correlated with caregiver burden in SD (R > L) patients, although more than half of these individuals were depressed. Sabodash et al. [29] suggested that SD patients have a higher risk of suicide, especially those with depression and insight about their disease. With respect to depression in SD (L > R) and SD (R > L), more detailed research is needed, including an examination of the relationship between patient levels of depression and caregiver burden.

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, the sample size was relatively small, especially for each type of SD due to the rarity of the disease. However, our sample size was comparable to those in previous studies of patients with SD [12, 13, 30] and was sufficiently large to perform statistical analyses. Second, this is a cross-sectional study targeted at participants who were first-visit outpatients. Hsieh et al. [31] reported that the level of caregiver burden in SD increased with the progression of the disease, whereas that in bvFTD remained high. Longitudinal investigations would be beneficial in future studies. Third, we could not examine the environmental and familial factors associated with caregiver burden. Fourth, progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA), which is 1 of 3 subtypes of FTD, was not examined in our study because of the limited number of participants. The level of caregiver burden in PNFA is reported to be lower than that in bvFTD and to be similar to that in Alzheimer disease [32]. Further studies should clarify factors associated with caregiver burden in PNFA.

In conclusion, we found that the caregiver burden for patients with SD (L > R) was relatively low, whereas that for patients with SD (R > L) was comparatively high. Caregivers for patients with bvFTD had the highest level of burden. Caregiver burden was correlated with BPSD scores, and factors related to caregiver burden differed between the bvFTD, SD (L > R), and SD (R > L) groups. In supporting caregivers, it is necessary to understand the features of burden of each type of FTLD and to develop an interventional approach.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

M. Ikeda and A. Koyama conceived of the study and undertook the study design. N. Ichimi, A. Takasaki, and A. Koyama collected the data. A. Koyama and M. Matsushita performed the analysis. M. Hashimoto, R. Fukuhara, T. Ishikawa, and M. Ikeda gave advice about the study design and data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant provided by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) grant number 26780306 (Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists [B]) for A.K. and 26461750 (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [C]) for M.I. The present study was also undertaken with the support of grants provided by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Research on Dementia; H27–29 Longevity-General-004) for M.I.

References

- 1.Ornstein K, Gaugler JE. The problem with “problem behaviors”: a systematic review of the association between individual patient behavioral and psychological symptoms and caregiver depression and burden within the dementia patient-caregiver dyad. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1536–1552. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svendsboe E, Terum T, Testad I, Aarsland D, Ulstein I, Corbett A, Rongve A. Caregiver burden in family carers of people with dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31:1075–1083. doi: 10.1002/gps.4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuijpers P. Depressive disorders in caregivers of dementia patients: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:325–330. doi: 10.1080/13607860500090078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J, Wang LN, Tan JP, Ji P, Gauthier S, Zhang YL, Ma TX, Liu SN. Burden, anxiety and depression in caregivers of veterans with dementia in Beijing. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:560–563. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joling KJ, van Marwijk HWJ, Veldhuijzen AE, van der Horst HE, Scheltens P, Smit F, van Hout HPJ. The two-year incidence of depression and anxiety disorders in spousal caregivers of persons with dementia: who is at the greatest risk? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;23:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz R, Newsom J, Mittelmark M, Burton L, Hirsch C, Jackson S. Health effects of caregiving: the caregiver health effects study: an ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19:110–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02883327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koyama A, Matsushita M, Hashimoto M, Fujise N, Ishikawa T, Tanaka H, Hatada Y, Miyagawa Y, Hotta M, Ikeda M. Mental health among younger and older caregivers of dementia patients. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17:108–114. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crellin NE, Orrell M, McDermott O, Charlesworth G. Self-efficacy and health-related quality of life in family careers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18:1–16. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.915921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lima-Silva TB, Bahia VS, Carvalho VA, Guimarães HC, Caramelli P, Balthazar ML, Damasceno B, Bottino CM, Brucki SM, Nitrini R, Yassuda MS. Neuropsychiatric symptoms, caregiver burden and distress in behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2015;40:268–275. doi: 10.1159/000437351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu S, Jin Y, Shi Z, Huo YR, Guan Y, Liu M, Liu S, Ji Y. The effects of behavioral and psychological symptoms on caregiver burden in frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, and Alzheimer's disease: clinical experience in China. Aging Ment Health. 2016;16:1–7. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1146871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caceres BA, Frank MO, Jun J, Martelly MT, Sadarangani T, De Sales PC. Family caregivers of patients with frontotemporal dementia: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;55:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uflacker A, Edmondson M-C, Onyike CU, Appleby BS. Caregiver burden in atypical dementias: comparing frontotemporal dementia, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28:269–273. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215001647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson SA, Patterson K, Hodges JR. Left/right asymmetry of atrophy in semantic dementia: behavioral-cognitive implications. Neurology. 2003;61:1196–1203. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000091868.28557.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kashibayashi T, Ikeda M, Komori K, Shinagawa S, Shimizu H, Toyota Y, Mori T, Ishikawa T, Fukuhara R, Ueno S, Tanimukai S. Transition of distinctive symptoms of semantic dementia during longitudinal clinical observation. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29:224–232. doi: 10.1159/000269972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH, Neuhaus J, van Swieten JC, Seelaar H, Dopper EG, Onyike CU, Hillis AE, Josephs KA, Boeve BF, Kertesz A, Seeley WW, Rankin KP, Johnson JK, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rosen H, Prioleau-Latham CE, Lee A, Kipps CM, Lillo P, Piguet O, Rohrer JD, Rossor MN, Warren JD, Fox NC, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Black SE, Mesulam M, Weintraub S, Dickerson BC, Diehl-Schmid J, Pasquier F, Deramecourt V, Lebert F, Pijnenburg Y, Chow TW, Manes F, Grafman J, Cappa SF, Freedman M, Grossman M, Miller BL. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134:2456–2477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, Freedman M, Kertesz A, Robert PH, Albert M, Boone K, Miller BL, Cummings J, Benson DF. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oldfield RC. The assessment of handedness: the Edinburgh Inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arai Y, Kudo K, Hosokawa T, Washio M, Miura H, Hisamichi S. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden interview. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;51:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1997.tb03199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hokoishi K, Ikeda M, Maki N, Nebu A, Shigenobu K, Tanabe H. Validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the Physical Self-Maintenance Scale and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (in Japanese) J Jpn Med Assoc. 1999;122:110–114. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirono N, Mori E, Ikejiri Y, Imamura T, Shimomura T, Hashimoto M, Yamashita H, Ikeda M. Japanese version of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory – a scoring system for neuropsychiatric disturbances in dementia patients (in Japanese) No To Shinkei. 1997;49:266–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diehl-Schmid J, Schmidt EM, Nunnemann S, Riedl L, Kurz A, Förstl H, Wagenpfeil S, Cramer B. Caregiver burden and needs in frontotemporal dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;26:221–229. doi: 10.1177/0891988713498467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mioshi E, Kipps CM, Dawson K, Mitchell J, Graham A, Hodges JR. Activities of daily living in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;68:2077–2084. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264897.13722.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Küçükgüçlü Ö, Söylemez BA, Yener G, Barutcu CD, Akyol MA. Examining factors affecting caregiver burden: a comparison of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2017;32:200–206. doi: 10.1177/1533317517703479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabodash V, Mendez MF, Fong S, Hsiao JJ. Suicidal behavior in dementia: a special risk in semantic dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:592–599. doi: 10.1177/1533317513494447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merrilees J, Dowling GA, Hubbard E, Mastick J, Ketelle R, Miller BL. Characterization of apathy in persons with frontotemporal dementia and the impact on family caregivers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27:62–67. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182471c54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsieh S, Leyton CE, Caga J, Flanagan E, Kaizik C, O'Connor CM, Kiernan MC, Hodges JR, Piguet O, Mioshi E. The evolution of caregiver burden in frontotemporal dementia with and without amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49:875–885. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mioshi E, Foxe D, Leslie F, Savage S, Hsieh S, Miller L, Hodges JR, Piguet O. The impact of dementia severity on caregiver burden in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27:68–73. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318247a0bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]