Serine carboxypeptidases Prc1 and newly characterized Atg42/Ybr139w are vacuolar proteases required for recycling of amino acids, zymogen activation, and the terminal steps of autophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Abstract

Macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy) is a cellular recycling pathway essential for cell survival during nutrient deprivation that culminates in the degradation of cargo within the vacuole in yeast and the lysosome in mammals, followed by efflux of the resultant macromolecules back into the cytosol. The yeast vacuole is home to many different hydrolytic proteins and while few have established roles in autophagy, the involvement of others remains unclear. The vacuolar serine carboxypeptidase Y (Prc1) has not been previously shown to have a role in vacuolar zymogen activation and has not been directly implicated in the terminal degradation steps of autophagy. Through a combination of molecular genetic, cell biological, and biochemical approaches, we have shown that Prc1 has a functional homologue, Ybr139w, and that cells deficient in both Prc1 and Ybr139w have defects in autophagy-dependent protein synthesis, vacuolar zymogen activation, and autophagic body breakdown. Thus, we have demonstrated that Ybr139w and Prc1 have important roles in proteolytic processing in the vacuole and the terminal steps of autophagy.

INTRODUCTION

The vacuole in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is analogous to the mammalian lysosome and performs a variety of functions, including metabolite storage and maintenance of pH and ion homeostasis, but it is perhaps best known as the major degradative organelle of the cell (Klionsky et al., 1990; Thumm, 2000). Macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy) is an intracellular recycling pathway that depends on the vacuole for degradation of various substrates (Reggiori and Klionsky, 2013). On induction of autophagy by nutrient stress conditions such as nitrogen starvation, transient membrane compartments, called phagophores, form de novo to envelop cellular contents. The phagophore expands, and on completion forms an autophagosome. Autophagosomes traffic to the vacuole, where the outer membrane of the autophagosome fuses with the vacuolar membrane, releasing the inner membrane-bound compartment, now termed the autophagic body, into the vacuolar lumen. The autophagic body and its contents are broken down and released back into the cytosol for reuse by the cell (Reggiori and Klionsky, 2013).

Although autophagy has attracted substantial attention since the late 1990s, and defects in this process are associated with a wide array of diseases, relatively little attention has been focused on the final steps of this process—breakdown of the autophagic cargo and efflux of the resulting macromolecules. As a degradative organelle, the vacuole is home to many hydrolases, responsible for degrading a wide array of substrates, including proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids (Klionsky et al., 1990; Epple et al., 2001; Teter et al., 2001). As with the final breakdown process in general, the biosynthesis and function of vacuolar/lysosomal hydrolases have been largely ignored in recent years, yet there are clearly many unanswered questions about hydrolase function. For example, several of these enzymes appear to have redundant activities: the yeast vacuole contains at least two carboxypeptidases and two aminopeptidases (Klionsky et al., 1990; Van Den Hazel et al., 1996; Hecht et al., 2014); however, it is likely that each of these enzymes has at least some unique substrates and specificities. In fact, the absence of a single lysosomal hydrolase often results in a disease phenotype (Kaminskyy and Zhivotovsky, 2012). As one example, patients with the disease galactosialidosis exhibit a deficiency of the multifunctional lysosomal hydrolase cathepsin A (CTSA) (Hiraiwa, 1999). CTSA functions as a carboxypeptidase and has structural homology to, and similar substrate specificity as, the yeast vacuolar serine carboxypeptidase Y (Prc1) (Hiraiwa, 1999).

In yeast, two resident vacuolar proteases in particular, Pep4 (proteinase A) and Prb1 (proteinase B), are critical for the final steps of autophagy, in part because they play a role in the activation of many of the other zymogens present in the vacuole lumen (Van Den Hazel et al., 1996). Cells deficient in these proteases show an accumulation of autophagic bodies in the vacuole (Takeshige et al., 1992). Additionally, cells lacking Pep4 display decreased survival in nitrogen starvation conditions (Teichert et al., 1989; Tsukada and Ohsumi, 1993). During times of nutrient stress, cells will increase expression of Pep4, Prb1, and Prc1 to cope with the increased demand for autophagic recycling (Klionsky et al., 1990; Van Den Hazel et al., 1996). Thus far, Prc1 has not been shown to have a role in autophagy, as there is no accumulation of autophagic bodies in the vacuoles of Prc1-deficient cells during nitrogen starvation (Takeshige et al., 1992). However, this may be due to the presence of a functionally redundant homologue; the vacuole contains one other putative serine carboxypeptidase, Ybr139w, which shows a high degree of similarity to Prc1 at the amino acid level; the other known vacuolar carboxypeptidase, Cps1, is a zinc metallopeptidase (Nasr et al., 1994; Huh et al., 2003; Baxter et al., 2004; Hecht et al., 2014). Microarray and Northern blotting analysis show that YBR139W expression is induced in nitrogen-poor conditions or following rapamycin treatment (Scherens et al., 2006). In one study examining the synthesis of phytochelatins, peptides that bind excess heavy metal ions, deletion of YBR139W had little-to-no effect on synthesis, whereas deletion of PRC1 resulted in moderate inhibition of synthesis (Wünschmann et al., 2007). However, deletion of both genes abolished phytochelatin synthesis altogether (Wünschmann et al., 2007). This finding suggests that there may indeed be some functional redundancy between these two proteins. Thus, it is possible that no autophagy phenotype has yet been seen in Prc1-deficient cells due to a compensatory effect by Ybr139w.

We set out to determine whether Ybr139w is a functional homologue of Prc1 and whether either or both of these proteins participate in the terminal steps of autophagy. We demonstrate that the absence of both of these proteins results in defects in the maturation of several vacuolar hydrolases, lysis of autophagic bodies in the vacuole, and maintenance of the amino acid pool during nitrogen starvation conditions. Additionally, there is functional redundancy between Prc1 and Ybr139w as regards these phenotypes.

RESULTS

Ybr139w is a resident vacuolar glycoprotein

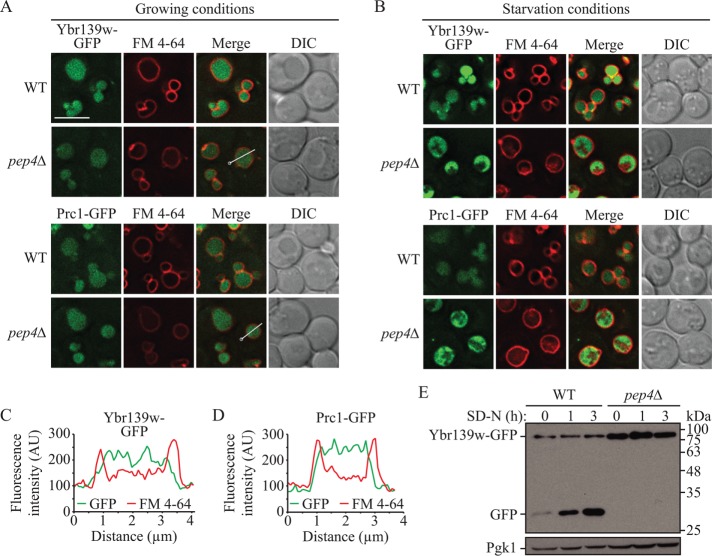

As can be inferred from the absence of a standard name, Ybr139w has been essentially uncharacterized. A previous large-scale study of protein localization indicated that Ybr139w localized to the vacuole, similarly to Prc1 (Huh et al., 2003). To verify this localization, we tagged the carboxy terminus of Ybr139w with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and examined its intracellular distribution using fluorescence microscopy. In both growing and starvation conditions, Ybr139w-GFP localized to the vacuole and displayed a diffuse signal throughout the lumen, similar to Prc1-GFP (Figure 1, A and B). Similarly, in the pep4∆ strain, where most proteolytic processing is blocked, localization was diffuse throughout the vacuole lumen. Line plots of the fluorescence intensity through a representative image indicated a staining pattern that was distinct from the vacuolar membrane dye FM 4-64 (Figure 1, C and D). This finding was in stark contrast to the localization of GFP-Pho8 and Cps1-GFP (Supplemental Figure S1). Pho8 is a vacuolar integral membrane protein (Klionsky and Emr, 1989). Consistent with this, GFP-Pho8 localizes primarily to the vacuolar membrane, and line plots showed a clear overlap of the GFP signal with the vacuole membrane in either the wild-type or pep4∆ backgrounds (Supplemental Figure 1C). Cps1 is delivered to the vacuole via the multivesicular body (MVB) pathway (Odorizzi et al., 1998). In the pep4∆ strain, Cps1-GFP remains associated with intact MVBs within the vacuole (Reggiori and Pelham, 2001), leading to a patchy intravacuolar GFP signal distinct from that of both Ybr139w-GFP and Prc1-GFP (Supplemental Figure 1, A and D). The diffuse staining of Cps1-GFP, which transits to the vacuole as a membrane protein, is not due to cleavage of the GFP moiety; Western blot shows that Cps1-GFP was present primarily as the full-length chimera, particularly in the pep4∆ strain (Supplemental Figure 1D). These results suggest that, like Prc1, Ybr139w is a soluble, rather than membrane-associated, vacuolar protein.

FIGURE 1:

Ybr139w is a soluble vacuolar protein. The localization of Ybr139w-GFP and Prc1-GFP was examined in wild-type (KPY382 and KPY384) and pep4∆ (KPY383 and KPY385) cells in (A) growing and (B) starvation conditions. FM 4-64 was used to label the vacuole limiting membrane. DIC, differential interference contrast. Scale bar: 5 µm. (C, D) Line profile plot of fluorescence intensity along the line in the Ybr139w-GFP pep4∆ and Prc1-GFP pep4∆ strains from the “merge” panels in A; the circle indicates the line profile starting point. (E) GFP is cleaved from Ybr139w-GFP in a PEP4-dependent manner. Wild-type (KPY382) and pep4∆ (KPY383) cells expressing chromosomally tagged Ybr139w-GFP were grown to mid–log phase in YPD and then shifted to starvation conditions for the indicated times. Protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot using antibodies to YFP. Pgk1 is used as a loading control.

Many chimeric GFP-tagged proteins that are delivered to the vacuole undergo cleavage of intact GFP from the remainder of the protein (Shintani and Klionsky, 2004; Kanki and Klionsky, 2008); the GFP moiety is relatively resistant to degradation, and the appearance of the free GFP band serves as an indication of vacuolar delivery. Western blot analysis of protein extracts from cells expressing Ybr139w-GFP showed that GFP was cleaved from the chimera in a Pep4-dependent manner in both growing and starvation conditions (Figure 1E), providing further evidence that Ybr139w is exposed to the proteolytic environment of the vacuole. Together, these results suggest that, similar to Prc1, Ybr139w is a resident vacuolar protein.

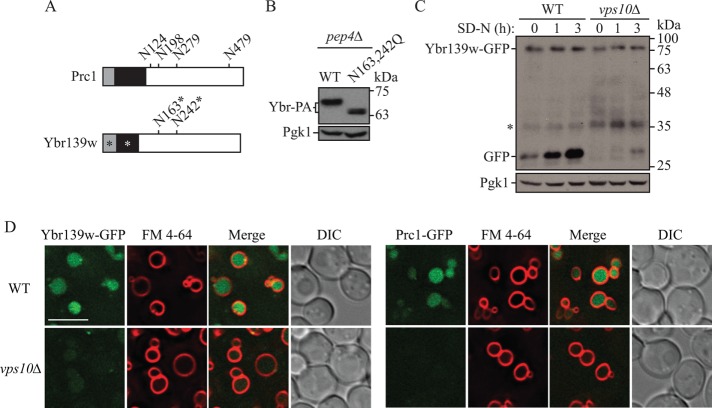

As with many of the vacuolar proteases, Prc1 is a glycoprotein (Klionsky et al., 1990; Van Den Hazel et al., 1996). Prc1 is N-glycosylated at Asn124, Asn198, Asn279, and Asn479 (Hasilik and Tanner, 1978a, b; Winther et al., 1991) (Figure 2A). Based on a Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) alignment, two of these sites, Asn198 and Asn279, are conserved in Ybr139w as Asn163 and Asn242. To determine whether Ybr139w is glycosylated at these sites, we mutated them to glutamine and looked for a change in gel mobility using Western blotting. Mutation of the predicted glycosylated residues resulted in a reduction in apparent molecular mass of ∼5 kDa, which would correspond to the average mass of two glycosylation sites (Figure 2B). This observation suggests that Ybr139w is glycosylated at these two conserved sites.

FIGURE 2:

Ybr139w is a glycoprotein dependent on Vps10 for vacuolar delivery. (A) Schematic representation of Prc1 and Ybr139w. Gray box, signal peptide; black box, propeptide; numbers, glycosylated residues; *, predicted. (B) pep4∆ (TVY1) cells expressing wild-type (WT; pKP105) Ybr139w-PA (Ybr-PA) or Ybr139wN163,242Q-PA (N163,242Q; pKP110) on plasmids were grown to mid–log phase in SMD-uracil (URA), cells were harvested, and protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot using antibodies to protein A. (C) GFP is cleaved from Ybr139w-GFP in a VPS10-dependent manner. Wild-type (KPY382) and vps10∆ (KPY424) cells expressing chromosomally tagged Ybr139w-GFP were grown to mid–log phase in YPD and then shifted to starvation conditions for the indicated times. Protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot using antibodies to YFP. (D) The localization of Ybr139w-GFP and Prc1-GFP was examined in wild-type (KPY382 and KPY384) and vps10∆ (KPY424 and KPY426) cells in growing conditions. FM 4-64 was used to label the vacuole limiting membrane. DIC, differential interference contrast. Scale bar: 5 µm.

Vacuolar delivery of Prc1 following glycosylation in the Golgi is dependent on the sorting receptor Vps10 (Marcusson et al., 1994). To determine whether Ybr139w follows the same vacuolar delivery pathway as Prc1, we examined cleavage of GFP from the Ybr139w-GFP fusion protein in both wild-type and Vps10-deficient cells. In the wild-type cells, GFP was cleaved from the Ybr139w-GFP fusion protein under both growing and starvation conditions (Figure 2C), as has been described (Figure 1E). In a strain lacking VPS10, however, GFP cleavage was severely impaired (Figure 2C). This suggests either that Vps10 is required for the delivery of Ybr139w-GFP to the vacuole or that Prc1, which depends on Vps10 for vacuolar delivery, is required for the degradation of Ybr139w or cleavage of the GFP tag. To address these possibilities, we examined the intracellular localization of Ybr139w-GFP in both wild-type and vps10∆ cells using fluorescence microscopy. In wild-type cells, both Prc1-GFP and Ybr139w-GFP localize to the vacuole (Figures 1 and 2D). As expected, vacuolar levels of Prc1-GFP were drastically reduced in Vps10-deficient cells (Figure 2D). Ybr139w-GFP was similarly excluded from the vacuole in the vps10∆ strain (Figure 2D), suggesting that Vps10 is the vacuolar sorting receptor for Ybr139w.

prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells exhibit defects in vacuolar function

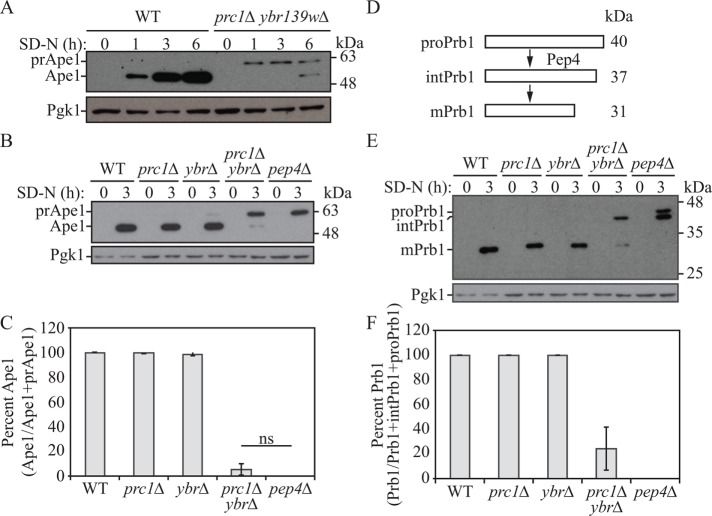

One important function of the yeast vacuole during autophagy is to generate a pool of free amino acids to be used in the synthesis of proteins. During nitrogen starvation, cellular amino acid levels decrease drastically but are largely recovered after 3–4 h (Onodera and Ohsumi, 2005; Müller et al., 2015); this recovery is dependent on autophagy and is required to support the increased synthesis of various proteins (Onodera and Ohsumi, 2005; Müller et al., 2015). One such protein that displays a substantial increase in synthesis under autophagy-inducing conditions is aminopeptidase 1 (Ape1), a resident vacuolar hydrolase that is delivered to the vacuole through the cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting (Cvt) pathway (Harding et al., 1995; Gasch et al., 2000). Under conditions of nitrogen starvation, Ape1 is dependent on the release of amino acids from the vacuolar pool for its increased synthesis (Onodera and Ohsumi, 2005; Yang et al., 2006). Thus, the level of Ape1 during starvation serves as a useful marker for vacuolar function and recycling of amino acids. Accordingly, we monitored the synthesis of this protein when cells were shifted from growing to starvation conditions. Whereas a robust increase in Ape1 occurred in wild-type cells upon nitrogen starvation, this was markedly reduced in prc1∆ ybr139w∆ double-knockout cells (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure S2A), suggesting a defect in the generation or efflux of the vacuolar amino acid pool in these cells; considering the soluble nature of Ybr139w and its similarity to Prc1, the former seems most likely. We also noted that the proteolytic processing of the precursor form of Ape1 (prApe1) was substantially delayed in prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells (Figure 3A) (Hecht et al., 2014). The prc1∆ ybr139w∆ double-knockout cells accumulated prApe1, similar to proteolytically deficient pep4∆ cells (Figure 3, B and C, and Supplemental Figure S2C). In contrast, neither the prc1∆ nor the ybr139w∆ single null strain displayed a defect in the synthesis or processing of prApe1 (Figure 3, B and C), suggesting that there is at least some degree of functional redundancy between Prc1 and Ybr139w.

FIGURE 3:

Vacuolar function is impaired in cells lacking PRC1 and YBR139W. (A) Wild-type (SEY6210) and prc1∆ ybr139w∆ (KPY325) cells were grown to mid–log phase in YPD and then shifted to starvation conditions for the indicated times. Protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot using antiserum to Ape1. The positions of precursor (pr) and mature Ape1 are indicated. (B, E) Wild-type (SEY6210), prc1∆ (KPY301), ybr139w∆ (KPY323), prc1∆ ybr139w∆ (KPY325), and pep4∆ (TVY1) cells were grown to mid–log phase in YPD and then shifted to starvation conditions for 3 h. Cells were harvested and protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot using antiserum to Ape1 (B) or Prb1 (E). The positions of the precursor (pro), intermediate (int), and mature forms of Prb1 are indicated. (C) Quantification of results in B. Percentage of Ape1 was calculated as amount of Ape1/total Ape1 (Ape1 + prApe1). Average of three experiments. Error bars, SD; ns, not significant. (D) Schematic representation of Prb1 processing in the vacuole. See text for details. (F) Quantification of results in E. Average of three experiments. Percentage of Prb1 was calculated as amount of Prb1/total Prb1 (Prb1 + intPrb1 + proPrb1). Average of three experiments. Error bars, SD.

Another marker for vacuolar recycling of amino acids is Prb1, which, like Ape1, is up-regulated during nitrogen starvation and is synthesized as a zymogen (Klionsky et al., 1990; Van Den Hazel et al., 1996; Hecht et al., 2014). Prb1 undergoes a self-catalyzed N-terminal cleavage event in the ER followed by glycosylation, resulting in a 40-kDa species (proPrb1) being delivered to the vacuole (Nebes and Jones, 1991; Hirsch et al., 1992; Van Den Hazel et al., 1996). Once in the vacuole, it undergoes two more cleavage events, this time at the C terminus. The first cleavage is Pep4-mediated and results in a 37-kDa intermediate species (Moehle et al., 1989), which we have termed intPrb1 (Figure 3D). The second cleavage event results in the 31-kDa mature form of Prb1 (Moehle et al., 1989). Similar to the Ape1 biosynthesis defects seen in the prc1∆ ybr139w∆ strain, Prb1 levels were lower and proteolytic processing was reduced compared with the wild type (Figure 3, E and F, and Supplemental Figure S2, B and C). The migration pattern of Prb1 in the prc1∆ ybr139w∆ double-knockout strain, however, was not identical to that seen in the pep4∆ strain (Figure 2E); the pep4∆ mutant showed a mix of the proPrb1 and intPrb1 precursors, whereas prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells accumulated intPrb1 and mature Prb1, suggesting that the initial cleavage event in the vacuole depends on Pep4 but that subsequent maturation requires the activity of these carboxypeptidases, at least for maximal efficiency; neither of these steps appeared to be completely blocked in pep4∆ or prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells, respectively, suggesting the possibility of less efficient compensatory processing mechanisms. The defect in protein synthesis and processing of prApe1 and intPrb1 were complemented by addition of either YBR139W or PRC1 genes to the prc1∆ ybr139w∆ strain (Supplemental Figure S3). On the basis of these data, we conclude that Ybr139w and Prc1 share some functional redundancy and in cells lacking both of these proteins, vacuolar function is impaired, as demonstrated by effects on protein synthesis under starvation conditions and proteolytic processing of certain zymogens.

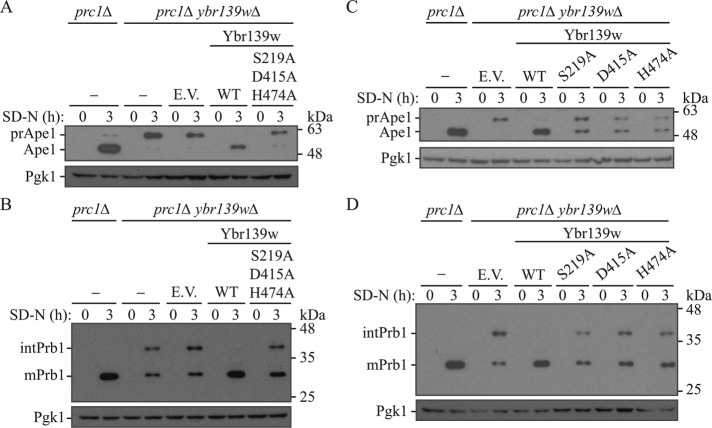

Ybr139w is a serine carboxypeptidase

To determine whether Ybr139w exhibited serine carboxypeptidase activity similar to Prc1, we sought to assess potential serine carboxypeptidase activity through mutagenesis of the predicted Ybr139w active site. Serine proteases have a catalytic triad consisting of a serine, histidine, and aspartate (Kraut, 1977). In Prc1, these residues are at positions Ser257, Asp449, and His508 (Stennicke et al., 1996). Mutation of either Ser257 or His508 to alanine drastically reduces the activity of Prc1 (Bech and Breddam, 1989; Stennicke et al., 1996), whereas mutating Asp449 has only a minor effect (Stennicke et al., 1996). The analogous residues in Ybr139w are Ser219, Asp415, and His474 (Nasr et al., 1994). Mutation of all three predicted active site residues to alanine abolished enzymatic activity, as evidenced by the inability of the mutated Ybr139w to complement the prApe1- and intPrb1-processing defects in prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells (Figure 4, A and B, and Supplemental Figure S4A); although we detected partial processing of intPrb1, a similar result was seen with the nontransformed prc1∆ ybr139w∆ strain or the double-knockout strain transformed with an empty vector. Mutation of individual residues showed only a partial block in enzymatic activity (Figure 4, C and D, and Supplemental Figure S4B). These results suggest that Ybr139w functions as a serine carboxypeptidase, similar to Prc1.

FIGURE 4:

Ybr139w is a serine carboxypeptidase. (A, B) prc1∆ (KPY301), prc1∆ ybr139w∆ (KPY325), and prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells with integrated empty vector (KPY332), Ybr139w (KPY336), or Ybr139wS219,D415,H474A (KPY418) were grown to mid–log phase in YPD and then shifted to starvation conditions for 3 h. Cells were harvested and protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot using antiserum to Ape1 (A) or Prb1 (B). (C, D) prc1∆ (KPY301) and prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells with integrated empty vector (KPY332), or expressing Ybr139w (KPY336), Ybr139wS219A (KPY404), Ybr139wD415A (KPY416), or Ybr139wH474A (KPY406) were grown to mid–log phase in YPD and then shifted to starvation conditions for 3 h. Cells were harvested and protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot using antiserum to Ape1 (C) or Prb1 (D).

We next used a complementary in vitro biochemical assay to measure the carboxypeptidase Y activity of various mutants. Hydrolysis of the Prc1 peptide substrate N-(3-[2-furyl]acryloyl)-Phe-Phe-OH (FA-Phe-Phe-OH) added to cell lysates results in a decrease in absorbance at 337 nm (Caesar and Blomberg, 2004; Gombault et al., 2009). As expected, wild-type cells showed a decrease in absorbance over time, indicative of carboxypeptidase Y activity in the cell lysates (Supplemental Figure S5). Deletion of PRC1 or both PRC1 and YBR139W almost completely abolished carboxypeptidase Y activity, whereas deletion of YBR139W alone had little to no effect. We propose that the observed results are due to a difference in substrate specificity between Prc1 and Ybr139w.

prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells are defective in the terminal steps of autophagy

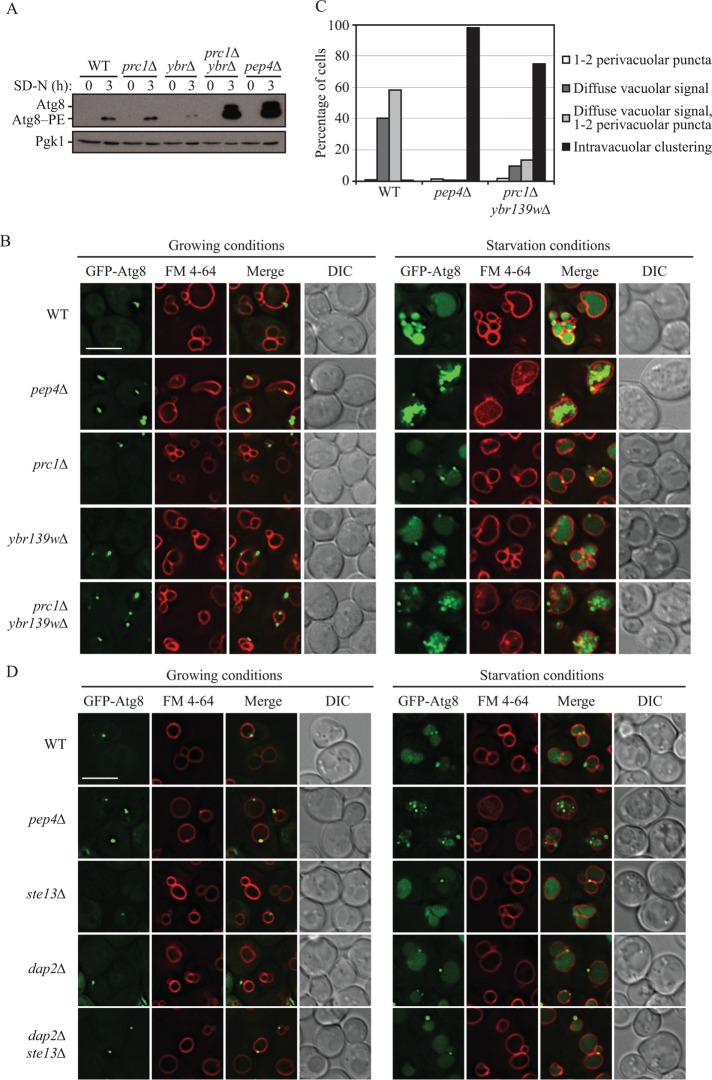

Because prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells showed a clear defect in vacuolar function, we next wanted to determine whether autophagy was affected in these cells. Autophagy-related 8 (Atg8) is an autophagic protein that becomes conjugated to a phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) lipid moiety in the cytoplasm (Ichimura et al., 2000). Atg8–PE is present on both sides of the phagophore, and the protein that is localized to the concave side becomes trapped within the completed autophagosome (Kirisako et al., 1999). This population of Atg8–PE is delivered into the vacuole within the autophagic body and is degraded during autophagy but accumulates in the vacuoles of pep4∆ cells (Klionsky et al., 2007). We analyzed the potential role of Prc1 and Ybr139w in the vacuolar turnover of Atg8 by Western blot. In wild-type cells, relatively little Atg8 or Atg8–PE is detected, because the protein is degraded in the vacuole (Figure 5A and Supplemental S6A). In contrast, pep4∆ cells displayed the expected accumulation of this protein. In fact, pep4∆ cells accumulated both nonlipidated Atg8 and Atg8–PE. Atg8 synthesis increases during starvation (Kirisako et al., 1999); it is possible that the ineffective generation of amino acids from vacuolar hydrolysis in the absence of Pep4 results in a continued starvation signal, causing further upregulation of Atg8 synthesis, and the small size of the protein may leave it relatively insensitive to the limited pool of free amino acids. Deletion of PRC1 caused no change in Atg8/Atg8–PE accumulation as compared with wild type, whereas the ybr139w∆ strain showed a slight reduction in total Atg8/Atg8–PE (Figure 5A and Supplemental Figure S6A). In contrast to the single mutants, the prc1∆ ybr139w∆ double mutant showed a substantial accumulation of Atg8/Atg8–PE, comparable to that of the pep4∆ strain. Reintroduction of the PRC1 gene into the prc1∆ ybr139w∆ strain fully complemented this phenotype, whereas reintroduction of the YBR139W gene could only partially complement (Supplemental Figure S6, B and C); there was still a substantial accumulation of Atg8–PE, suggesting a continued partial starvation response. This finding demonstrates that the vacuolar serine carboxypeptidases participate in the terminal steps of autophagy and further supports the functional overlap between these two proteins.

FIGURE 5:

Cells lacking PRC1 and YBR139W are defective in the terminal steps of autophagy. (A) Wild-type (SEY6210), prc1∆ (KPY301), ybr139w∆ (KPY323), prc1∆ ybr139w∆ (KPY325), and pep4∆ (TVY1) cells were grown to mid–log phase in YPD and then shifted to starvation conditions for 3 h. Cells were harvested and protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot using antiserum to Atg8. (B) Wild-type (SEY6210), pep4∆ (TVY1), prc1∆ (KPY301), ybr139w∆ (KPY323), and prc1∆ ybr139w∆ (KPY325) cells expressing GFP-Atg8 from a plasmid were grown in SMD-TRP to mid–log phase. Cells were stained with FM 4-64 for 30 min to label the vacuole and chased in either SMD-TRP for 1 h (growing) or SD-N for 2 h (starvation) before imaging. DIC, differential interference contrast. Scale bar: 5 µm. (C) Quantification of results in B. Cells with GFP-Atg8-positive vacuoles were divided into four categories based on the appearance of the GFP signal as indicated. Wild-type, n = 311 cells; pep4∆, n = 481 cells; prc1∆ ybr139w∆, n = 391 cells. (D) Wild-type (SEY6210), pep4∆ (TVY1), ste13∆ (KPY428), dap2∆ (KPY442), and dap2∆ ste13∆ (KPY443) cells expressing GFP-Atg8 from a plasmid were grown in SMD-TRP to mid–log phase. Cells were stained with FM 4-64 for 30 min to label the vacuole and chased in either SMD-TRP for 1 h (growing) or SD-N for 2 h (starvation) before imaging. DIC, differential interference contrast. Scale bar: 5 µm.

Given that Prb1 cleaves the propeptide from prApe1 in the vacuole in a Pep4-dependent manner (i.e., Prb1 is the direct processing enzyme, but its activation requires Pep4) (Klionsky et al., 1992; Van Den Hazel et al., 1996), it is possible that the observed defects in prApe1 maturation in pep4∆ and prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells (Figure 3, A–C) are a result of the defects in Prb1 processing in these strains (Figure 3, E and F). However, a previous observation that cells deficient in Pep4 or Prb1 accumulate autophagic bodies in the vacuole upon nitrogen starvation suggests another possible explanation (Takeshige et al., 1992). In addition to delivery via the Cvt pathway (Harding et al., 1995), prApe1 can be delivered to the vacuole through nonspecific autophagy (Scott et al., 1996). We hypothesized that inefficient maturation of prApe1 in pep4∆ and prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells (Figure 3, A–C) resulted from impaired lysis of autophagic bodies in the vacuole, preventing exposure of this zymogen to the proteolytic environment of the vacuolar lumen. We investigated whether autophagic bodies accumulate in the vacuole in prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells by examining the localization of GFP-Atg8. In growing conditions, GFP-Atg8 appears diffuse in the cytosol and as a single perivacuolar punctum that corresponds to the phagophore assembly site (Kim et al., 2002). During nitrogen starvation, GFP-Atg8 is delivered to the vacuole via autophagy (Suzuki et al., 2001). In wild-type cells that undergo normal breakdown of autophagic bodies within the vacuole, GFP from GFP-Atg8 appears as a diffuse signal throughout the vacuolar lumen. However, if breakdown of autophagic bodies is impeded, such as in a pep4∆ strain, the GFP signal appears punctate within the vacuole, which corresponds to the presence of intact autophagic bodies (Kim et al., 2001; Klionsky et al., 2007). The deletion of PRC1 or YBR139W alone resulted in the presence of diffuse vacuolar GFP-Atg8 fluorescence upon nitrogen starvation, similar to wild-type cells (Figure 5, B and C). In contrast, deletion of both genes showed an accumulation of GFP-Atg8 puncta in the vacuole, similar to, but not as severe as, the pep4∆ strain (Figure 5, B and C). This result suggests that at least one of the serine carboxypeptidases, Ybr139w or Prc1, must be present for efficient lysis of autophagic bodies in the vacuole lumen. Reintroduction of either Prc1 or Ybr139w into the double-knockout strain complements prApe1 and intPrb1 processing as well as the diffuse localization of GFP-Atg8 throughout the vacuolar lumen (Supplemental Figure S6, D–F).

We next sought to determine whether the intravacuolar clustering of GFP-Atg8 puncta observed in the pep4∆ and prc1∆ ybr139w∆ cells is a general phenotype of cells with vacuolar protease defects. Deletion of the gene encoding the vacuolar hydrolase Dap2 (dipeptidyl amiopeptidase B) had no effect on the diffuse vacuolar localization of GFP-Atg8 during starvation (Figure 5D) (Roberts et al., 1989; Baxter et al., 2004). As Dap2 bears homology to Ste13 (Fuller et al., 1988), a protease that cycles between the trans-Golgi network and endosomal system (Johnston et al., 2005), we also deleted STE13 in either wild-type or dap2∆ cells. Neither the ste13∆ nor the dap2∆ ste13∆ strains showed an effect on GFP-Atg8 localization (Figure 5D). GFP-Atg8 was also seen to remain diffuse throughout the vacuoles of cells lacking Cps1 and/or its putative homologue Yol153c (unpublished data). These results indicate that accumulation of GFP-Atg8 puncta within the vacuole during starvation results from deficiencies in specific vacuolar proteases, including Prc1 and Ybr139w, rather than general vacuolar protease defects.

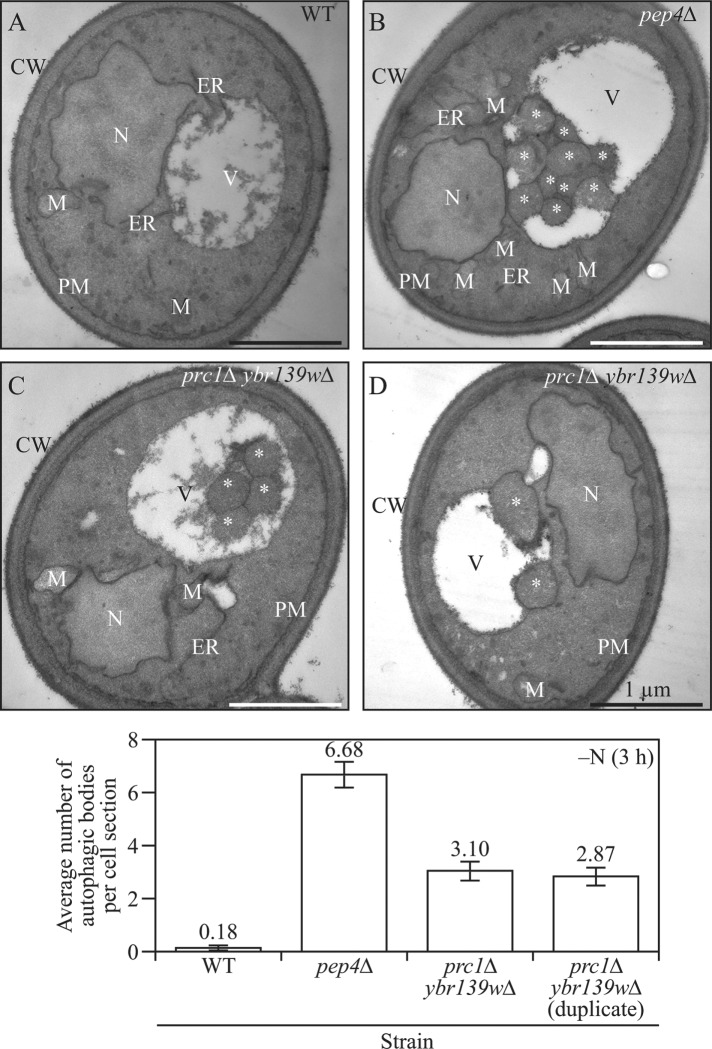

Finally, we decided to verify that the appearance of GFP-Atg8 puncta within the vacuole lumen was the result of autophagic body accumulation rather than protein aggregation resulting from elevated levels of the nondegraded chimera. Accordingly, we grew cells in nutrient-rich medium, shifted them to starvation conditions, and prepared samples for transmission electron microscopy (TEM). After 3 h of autophagy induction, wild-type cells accumulated less than 1 autophagic body per vacuole section (Figure 6). As expected, the pep4∆ positive-control strain, which is defective in autophagic body breakdown, was found to contain an average of 6.68 autophagic bodies per section. In agreement with a partial defect in Prb1 activity, two different isolates of a prc1∆ ybr139w∆ double-knockout strain accumulated ∼3 autophagic bodies per vacuole section, values that were statistically different from the wild type (Supplemental Table S1). These TEM data agree with our fluorescence microscopy analysis, and support the conclusion that the absence of both Prc1 and Ybr139w results in a defect in autophagic body breakdown.

FIGURE 6:

The prc1∆ ybr139w∆ double-knockout strain accumulated autophagic bodies. (A) Wild-type (SEY6210), (B) pep4∆ (FRY143), and (C, D) prc1∆ ybr139w∆ (KPY440 and KPY441 [an independent isolate]) cells were grown in YPD and shifted to SD-N for 3 h. Cells were then prepared for TEM analysis as described under Materials and Methods. Counting was done on three independent grids per condition and 100 cells per condition. Scale bars: 1 µm. *, autophagic body; CW, cell wall; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; M, mitochondria; N, nucleus; PM, plasma membrane; V, vacuole.

Owing to its roles in vacuolar function and the terminal steps of autophagy, we propose to rename YBR139W as ATG42.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we set out to characterize the putative Prc1 homologue Atg42/Ybr139w and to determine whether either or both of these proteins are involved in the terminal steps of autophagy. Through fluorescence microscopy and Western blotting, we demonstrated that, similar to Prc1, Atg42/Ybr139w is a resident soluble vacuolar glycoprotein dependent on the sorting receptor Vps10 for vacuolar delivery (Figures 1 and 2). Moreover, Atg42/Ybr139w was shown to be a serine carboxypeptidase (Figure 4) based on mutation of predicted active site residues that were identified through alignment with Prc1. However, we suggest that Atg42/Ybr139w may have a slightly different substrate specificity than Prc1, as prc1∆ cells showed an inability to break down the Prc1 substrate FA-Phe-Phe-OH, despite the presence of Atg42/Ybr139w (Supplemental Figure S5).

We also found that at least one of these proteins is required for regeneration of the vacuolar amino acid pool during starvation as demonstrated by the reduced synthesis of Ape1 in atg42∆/ybr139w∆ prc1∆ mutant cells (Figure 3A). Loss of both Atg42/Ybr139w and Prc1 also resulted in decreased maturation of the vacuolar zymogens prApe1 and intPrb1 (Figure 3, B, C, E, and F). Our results regarding the maturation defects of Prb1 in the atg42∆/ybr139w∆ prc1∆ strain in particular provide further information regarding the proteolytic processing of this protein. The second cleavage of the Prb1 zymogen, which occurs in the vacuole (conversion of intPrb1 to Prb1; Figure 3D), was previously reported to be Prb1-dependent (i.e., autocatalytic), because the Prb1 inhibitor chymostatin inhibits processing (Mechler et al., 1988). Also, the intPrb1 species accumulates in cells with the prb1-628 allele, in which Ala171 is changed to Thr; this mutation is thought to possibly interfere with the Prb1 active site (Moehle et al., 1989; Nebes and Jones, 1991). However, our data suggest that the second cleavage event is at least partially dependent on Atg42/Ybr139w and/or Prc1.

The vacuolar breakdown and efflux steps of autophagy are mediated by a host of hydrolases and permeases, including Pep4 and Prb1. Evidence of this exists in the accumulation of autophagic bodies in the vacuoles of Pep4- and Prb1-deficient cells (Takeshige et al., 1992). It was previously thought that Prc1 had no involvement in autophagy because deletion of the PRC1 gene had no effect on autophagic body formation in the vacuole (Takeshige et al., 1992). However, our work suggests that the role of Prc1 in autophagy was previously obscured due to compensatory activity by the homologue Atg42/Ybr139w in Prc1-deficient cells, and that both Prc1 and Atg42/Ybr139w do in fact participate in the terminal steps of autophagy. Analysis of prc1∆ or atg42∆/ybr139w∆ single mutant strains would seem to support the previous notion that neither of these genes are required for autophagy; Atg8 protein is turned over as in wild-type cells (Figure 5A), and GFP-Atg8 fluorescence is diffuse within vacuoles during nitrogen starvation (Figure 5B), suggesting efficient lysis of autophagic bodies within the vacuole. However, the atg42∆/ybr139w∆ prc1∆ double mutant was strikingly similar to the autophagy-deficient pep4∆ strain; there was a marked accumulation of Atg8 protein (Figure 5A), suggesting a defect in protein turnover, and GFP-Atg8 appeared primarily as punctate clusters within the vacuole, suggesting an accumulation of autophagic bodies and a defect in autophagic body lysis (Figure 5, B and C). Indeed, electron microscopy confirmed that autophagic bodies are present in the vacuoles of the atg42∆/ybr139w∆ prc1∆ double mutant (Figure 6).

It is unclear from our results how Atg42/Ybr139w and Prc1 function in the breakdown of autophagic bodies in the vacuole. As previously mentioned, autophagic bodies accumulate in Prb1- and Pep4-deficient cells (Takeshige et al., 1992), so one possibility is that the defects in Prb1 maturation seen in the atg42∆/ybr139w∆ prc1∆ strain are responsible for this block. Accumulation of autophagic bodies also occurs in cells lacking the vacuolar lipase Atg15 (Epple et al., 2001; Teter et al., 2001). How Atg15 activity is regulated in the vacuole remains unknown, but it has been previously speculated that, similar to many other vacuolar proteins, it may be activated through proteolytic processing (Teter et al., 2001). Further study is required to understand this activation and whether Atg42/Ybr139w, Prc1, and/or Prb1 are involved. The cascade of events that combines vacuolar acidification, zymogen activation, and the lipase Atg15 to result in autophagic body breakdown remains poorly understood; however, its importance cannot be overlooked—without these critical terminal events, autophagy cannot complete its recycling of macromolecules to support protein synthesis and survival during starvation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media

Yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. C-terminal tagging with GFP (Longtine et al., 1998) and gene disruption (Gueldener et al., 2002) were performed using a PCR-based method. Owing to slight overlap between the YBR139W gene and the chromosomal autonomously replicating sequence, we did not delete the entire gene but instead deleted nucleotides coding for the first 491 of 508 amino acids. We refer to this truncation as ybr139w∆ for simplicity. Site-directed mutagenesis of plasmid-borne YBR139W was done using a standard method (Zheng et al., 2004).

TABLE 1:

Strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| ARA107 | SEY6210 + pGO41 | This study |

| ARA108 | TVY1 + pGO41 | This study |

| FRY143 | SEY6210 vps4∆::TRP1 pep4∆::LEU2 | Cheong et al., 2005 |

| KPY301 | SEY6210 prc1∆::his5 | This study |

| KPY323 | SEY6210 ybr139w∆::LEU2 | This study |

| KPY325 | SEY6210 prc1∆::HIS5 ybr139w∆::LEU2 | This study |

| KPY332 | KPY325 + pKP112 | This study |

| KPY334 | KPY325 + pKP113 | This study |

| KPY336 | KPY325 + pKP115 | This study |

| KPY350 | SEY6210 + pRS406 | This study |

| KPY351 | KPY325 + pRS406 | This study |

| KPY382 | SEY6210 YBR139W-GFP(S65T)-His3MX6 | This study |

| KPY383 | TVY1 YBR139W-GFP(S65T)-His3MX6 | This study |

| KPY384 | SEY6210 PRC1-GFP(S65T)-His3MX6 | This study |

| KPY385 | TVY1 PRC1-GFP(S65T)-His3MX6 | This study |

| KPY404 | KPY325 + pKP129 | This study |

| KPY406 | KPY325 + pKP131 | This study |

| KPY410 | SEY6210 prb1∆::kanMX | This study |

| KPY416 | KPY325 + pKP133 | This study |

| KPY418 | KPY325 + pKP134 | This study |

| KPY420 | KPY325 + pKP135 (isolate #1) | This study |

| KPY421 | KPY325 + pKP135 (isolate #4) | This study |

| KPY422 | KPY325 + pKP136 (isolate #1) | This study |

| KPY423 | KPY325 + pKP136 (isolate #4) | This study |

| KPY424 | SEY6210 YBR139W-GFP(S65T)-His3MX6 vps10∆::kanMX | This study |

| KPY426 | SEY6210 PRC1-GFP(S65T)-His3MX6 vps10∆::kanMX | This study |

| KPY428 | SEY6210 ste13∆::URA3 | This study |

| KPY436 | SEY6210 CPS1-GFP(S65T)-kanMX6 | This study |

| KPY438 | TVY1 CPS1-GFP(S65T)-kanMX6 | This study |

| KPY440 | SEY6210 prc1∆::HIS5 ybr139w∆::LEU2 vps4∆::kanMX (isolate #6) | This study |

| KPY441 | SEY6210 prc1∆::HIS5 ybr139w∆::LEU2 vps4∆::kanMX (isolate #8) | This study |

| KPY442 | SEY6210 dap2∆::kanMX | This study |

| KPY443 | SEY6210 ste13∆::URA3 dap2∆::kanMX | This study |

| SEY6210 | MATα leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-∆200 trp1-∆901 suc2-∆9 lys2-801; GAL | Robinson et al., 1988 |

| TVY1 | SEY6210 pep4∆::LEU2 | Gerhardt et al., 1998 |

TABLE 2:

Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pGFP-Atg8 (414) | Abeliovich et al., 2003 | |

| pGO41 | pRS426 GFP-Pho8 | Cowles et al., 1997 |

| pKP105 | pRS416-YBR139Wp-YBR139W-PA-ADH1t | This study |

| pKP110 | pRS416-YBR139Wp-YBR139WN163,242Q-PA-ADH1t | This study |

| pKP112 | pRS406-GFP-ADH1t | This study |

| pKP113 | pRS406-PRC1p-PRC1-GFP-ADH1t | This study |

| pKP115 | pRS406-YBR139Wp-YBR139W-GFP-ADH1t | This study |

| pKP129 | pRS406-YBR139Wp-YBR139WS219A-GFP-ADH1t | This study |

| pKP131 | pRS406-YBR139Wp-YBR139WH474A-GFP-ADH1t | This study |

| pKP133 | pRS406-YBR139Wp-YBR139WD415A-GFP-ADH1t | This study |

| pKP134 | pRS406-YBR139Wp-YBR139WS219,D415,H474A-GFP-ADH1t | This study |

| pKP135 | pRS406-YBR139Wp-YBR139W-PA-ADH1t | This study |

| pKP136 | pRS406-PRC1p-PRC1-PA-ADH1t | This study |

| pRS406 | Sikorski and Hieter, 1989 |

Cells were cultured in rich medium (YPD; 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) or synthetic minimal medium (SMD; 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% glucose, and auxotrophic amino acids and vitamins as needed) as appropriate. Autophagy was induced by shifting cells in mid–log phase from growth medium to nitrogen starvation medium (SD-N; 0.17% yeast nitrogen base without ammonium sulfate or amino acids, 2% glucose) for the indicated times. All cells were grown at 30°C.

Protein extraction and immunoblot analysis

Protein extraction and immunoblotting were performed as previously described (Yorimitsu et al., 2007). PVDF membranes were stained with Ponceau S to monitor protein transfer prior to immunoblotting.

Antisera to Ape1 and Atg8 were used as described previously (Klionsky et al., 1992; Huang et al., 2000). The anti-Pgk1 antiserum was a generous gift from Jeremy Thorner (University of California, Berkeley). The anti-Prb1 antiserum was a generous gift from Elizabeth Jones (Moehle et al., 1989). Additional antisera used were anti-PA (Jackson Immunoresearch), anti-YFP (Clontech, JL-8), rabbit anti-mouse (Jackson Immunoresearch), and goat anti-rabbit (Fisher Scientific).

Fluorescence microscopy

For FM 4-64 (Life Technologies) vacuole membrane staining, cells were grown to mid-log phase in SMD complete medium or SMD medium lacking selective nutrients at 30°C. Cells (0.75 OD600 units) were collected by centrifugation at 855 × g for 1 min; pellets were resuspended in 100 µl growth medium and stained with 30 µM FM 4-64 for 30 min at 30°C, agitating every 10 min. Cells were then washed two times with 1 ml growth medium or starvation medium (SD-N), resuspended in 1 ml growth medium or SD-N, and incubated at 30°C for either 1 h (growth medium) or 2 h (starvation medium) before imaging.

Fluorescence line profiles were generated using softWoRx software (GE Healthcare).

Carboxypeptidase Y activity assay

Samples were prepared and carboxypeptidase Y activity was determined similar to the method described in Caesar and Blomberg (2004). Briefly, cells were lysed by glass bead disruption in MES buffer (50 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid, 1 mM EDTA, pH 6.5). Cell debris was pelleted, and the supernatant (lysate) was collected. The bicinchoninic acid assay was used to determine the protein concentration of the lysates.

Hydrolysis of the carboxypeptidase Y substrate N-(3-[2-furyl]acryloyl)-Phe-Phe (FA-Phe-Phe-OH; Bachem) was measured over time in MES buffer. Reactions contained 200 µg/ml lysate and 1 mM FA-Phe-Phe-OH (dissolved in methanol) and were incubated at room temperature. Hydrolysis of FA-Phe-Phe-OH was measured by reading the absorbance at 337 nm.

Transmission electron microscopy

Cells nitrogen starved for 3 h were fixed with potassium permanganate, dehydrated with acetone, and embedded with Spurr’s resin as described previously (Backues et al., 2014). Subsequently, cell sections were cut and stained with uranyl acetate before being imaged in an 80-kV CM100 transmission electron microscope (FEI).

Statistical analysis

Where appropriate, a one-sample t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Jones (decd. 2008) for providing the anti-Prb1 antiserum and Jeremy Thorner for providing the anti-Pgk1 antiserum. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM053396 to D.J.K. and Aard- en Levenswetenschappen (ALW) Open Programme grant ALWOP.355 to M.M.

Abbreviations used:

- Ape1

aminopeptidase 1

- Atg

autophagy-related

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- Pep4

proteinase A

- Prb1

proteinase B

- Prc1

carboxypeptidase Y

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E17-08-0516) on March 5, 2018.

REFERENCES

- Abeliovich H, Zhang C, Dunn WA, Shokat KM, Klionsky DJ. (2003). Chemical genetic analysis of Apg1 reveals a non-kinase role in the induction of autophagy. Mol Biol Cell , 477–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backues SK, Chen D, Ruan J, Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. (2014). Estimating the size and number of autophagic bodies by electron microscopy. Autophagy , 155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter SM, Rosenblum JS, Knutson S, Nelson MR, Montimurro JS, Di Gennaro JA, Speir JA, Burbaum JJ, Fetrow JS. (2004). Synergistic computational and experimental proteomics approaches for more accurate detection of active serine hydrolases in yeast. Mol Cell Proteomics , 209–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech LM, Breddam K. (1989). Inactivation of carboxypeptidase Y by mutational removal of the putative essential histidyl residue. Carlsberg Res Commun , 165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caesar R, Blomberg A. (2004). The stress-induced Tfs1p requires NatB-mediated acetylation to inhibit carboxypeptidase Y and to regulate the protein kinase A pathway. J Biol Chem , 38532–38543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong H, Yorimitsu T, Reggiori F, Legakis JE, Wang C-W, Klionsky DJ. (2005). Atg17 regulates the magnitude of the autophagic response. Mol Biol Cell , 3438–3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles CR, Odorizzi G, Payne GS, Emr SD. (1997). The AP-3 adaptor complex is essential for cargo-selective transport to the yeast vacuole. Cell , 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epple UD, Suriapranata I, Eskelinen E-L, Thumm M. (2001). Aut5/Cvt17p, a putative lipase essential for disintegration of autophagic bodies inside the vacuole. J Bacteriol , 5942–5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RS, Sterne RE, Thorner J. (1988). Enzymes required for yeast prohormone processing. Annu Rev Physiol , 345–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasch AP, Spellman PT, Kao CM, Carmel-Harel O, Eisen MB, Storz G, Botstein D, Brown PO. (2000). Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell , 4241–4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt B, Kordas TJ, Thompson CM, Patel P, Vida T. (1998). The vesicle transport protein Vps33p is an ATP-binding protein that localizes to the cytosol in an energy-dependent manner. J Biol Chem , 15818–15829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gombault A, Warringer J, Caesar R, Godin F, Vallée B, Doudeau M, Chautard H, Blomberg A, Bénédetti H. (2009). A phenotypic study of TFS1 mutants differentially altered in the inhibition of Ira2p or CPY. FEMS Yeast Res , 867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueldener U, Heinisch J, Koehler GJ, Voss D, Hegemann JH. (2002). A second set of loxP marker cassettes for Cre-mediated multiple gene knockouts in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res , e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding TM, Morano KA, Scott SV, Klionsky DJ. (1995). Isolation and characterization of yeast mutants in the cytoplasm to vacuole protein targeting pathway. J Cell Biol , 591–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasilik A, Tanner W. (1978a). Biosynthesis of the vacuolar yeast glycoprotein carboxypeptidase Y. Conversion of precursor into the enzyme. Eur J Biochem , 599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasilik A, Tanner W. (1978b). Carbohydrate moiety of carboxypeptidase Y and perturbation of its biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem , 567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht KA, O’Donnell AF, Brodsky JL. (2014). The proteolytic landscape of the yeast vacuole. Cell Logist , e28023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraiwa M. (1999). Cathepsin A/protective protein: an unusual lysosomal multifunctional protein. Cell Mol Life Sci , 894–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch HH, Schiffer HH, Müller H, Wolf DH. (1992). Biogenesis of the yeast vacuole (lysosome). Mutation in the active site of the vacuolar serine proteinase yscB abolishes proteolytic maturation of its 73-kDa precursor to the 41.5-kDa pro-enzyme and a newly detected 41-kDa peptide. Eur J Biochem , 641–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W-P, Scott SV, Kim J, Klionsky DJ. (2000). The itinerary of a vesicle component, Aut7p/Cvt5p, terminates in the yeast vacuole via the autophagy/Cvt pathways. J Biol Chem , 5845–5851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh WK, Falvo JV, Gerke LC, Carroll AS, Howson RW, Weissman JS, O’Shea EK. (2003). Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature , 686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura Y, Kirisako T, Takao T, Satomi Y, Shimonishi Y, Ishihara N, Mizushima N, Tanida I, Kominami E, Ohsumi M, et al (2000). A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation. Nature , 488–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston HD, Foote C, Santeford A, Nothwehr SF. (2005). Golgi-to-late endosome trafficking of the yeast pheromone processing enzyme Ste13p is regulated by a phosphorylation site in its cytosolic domain. Mol Biol Cell , 1456–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminskyy V, Zhivotovsky B. (2012). Proteases in autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta , 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki T, Klionsky DJ. (2008). Mitophagy in yeast occurs through a selective mechanism. J Biol Chem , 32386–32393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Huang W-P, Klionsky DJ. (2001). Membrane recruitment of Aut7p in the autophagy and cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathways requires Aut1p, Aut2p, and the autophagy conjugation complex. J Cell Biol , 51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Huang W-P, Stromhaug PE, Klionsky DJ. (2002). Convergence of multiple autophagy and cytoplasm to vacuole targeting components to a perivacuolar membrane compartment prior to de novo vesicle formation. J Biol Chem , 763–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisako T, Baba M, Ishihara N, Miyazawa K, Ohsumi M, Yoshimori T, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. (1999). Formation process of autophagosome is traced with Apg8/Aut7p in yeast. J Cell Biol , 435–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Cuervo AM, Seglen PO. (2007). Methods for monitoring autophagy from yeast to human. Autophagy , 181–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Cueva R, Yaver DS. (1992). Aminopeptidase I of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is localized to the vacuole independent of the secretory pathway. J Cell Biol , 287–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Emr SD. (1989). Membrane protein sorting: biosynthesis, transport and processing of yeast vacuolar alkaline phosphatase. EMBO J , 2241–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Herman PK, Emr SD. (1990). The fungal vacuole: composition, function, and biogenesis. Microbiol Rev , 266–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut J. (1977). Serine proteases: structure and mechanism of catalysis. Annu Rev Biochem , 331–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A, III, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. (1998). Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast , 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcusson EG, Horazdovsky BF, Cereghino JL, Gharakhanian E, Emr SD. (1994). The sorting receptor for yeast vacuolar carboxypeptidase Y is encoded by the VPS10 gene. Cell , 579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechler B, Hirsch HH, Müller H, Wolf DH. (1988). Biogenesis of the yeast lysosome (vacuole): biosynthesis and maturation of proteinase yscB. EMBO J , 1705–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehle CM, Dixon CK, Jones EW. (1989). Processing pathway for protease B of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol , 309–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Schmidt O, Angelova M, Faserl K, Weys S, Kremser L, Pfaffenwimmer T, Dalik T, Kraft C, Trajanoski Z, et al (2015). The coordinated action of the MVB pathway and autophagy ensures cell survival during starvation. Elife , e07736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr F, Bécam AM, Grzybowska E, Zagulski M, Slonimski PP, Herbert CJ. (1994). An analysis of the sequence of part of the right arm of chromosome II of S. cerevisiae reveals new genes encoding an amino-acid permease and a carboxypeptidase. Curr Genet , 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebes VL, Jones EW. (1991). Activation of the proteinase B precursor of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by autocatalysis and by an internal sequence. J Biol Chem , 22851–22857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odorizzi G, Babst M, Emr SD. (1998). Fab1p PtdIns(3)P 5-kinase function essential for protein sorting in the multivesicular body. Cell , 847–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onodera J, Ohsumi Y. (2005). Autophagy is required for maintenance of amino acid levels and protein synthesis under nitrogen starvation. J Biol Chem , 31582–31586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F, Klionsky DJ. (2013). Autophagic processes in yeast: mechanism, machinery and regulation. Genetics , 341–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F, Pelham HRB. (2001). Sorting of proteins into multivesicular bodies: ubiquitin-dependent and -independent targeting. EMBO J , 5176–5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CJ, Pohlig G, Rothman JH, Stevens TH. (1989). Structure, biosynthesis, and localization of dipeptidyl aminopeptidase B, an integral membrane glycoprotein of the yeast vacuole. J Cell Biol , 1363–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JS, Klionsky DJ, Banta LM, Emr SD. (1988). Protein sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation of mutants defective in the delivery and processing of multiple vacuolar hydrolases. Mol Cell Biol , 4936–4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherens B, Feller A, Vierendeels F, Messenguy F, Dubois E. (2006). Identification of direct and indirect targets of the Gln3 and Gat1 activators by transcriptional profiling in response to nitrogen availability in the short and long term. FEMS Yeast Res , 777–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SV, Hefner-Gravink A, Morano KA, Noda T, Ohsumi Y, Klionsky DJ. (1996). Cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting and autophagy employ the same machinery to deliver proteins to the yeast vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA , 12304–12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani T, Klionsky DJ. (2004). Cargo proteins facilitate the formation of transport vesicles in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. J Biol Chem , 29889–29894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski RS, Hieter P. (1989). A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics , 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stennicke HR, Mortensen UH, Breddam K. (1996). Studies on the hydrolytic properties of (serine) carboxypeptidase Y. Biochemistry , 7131–7141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Kirisako T, Kamada Y, Mizushima N, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. (2001). The pre-autophagosomal structure organized by concerted functions of APG genes is essential for autophagosome formation. EMBO J , 5971–5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshige K, Baba M, Tsuboi S, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. (1992). Autophagy in yeast demonstrated with proteinase-deficient mutants and conditions for its induction. J Cell Biol , 301–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichert U, Mechler B, Müller H, Wolf DH. (1989). Lysosomal (vacuolar) proteinases of yeast are essential catalysts for protein degradation, differentiation, and cell survival. J Biol Chem , 16037–16045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teter SA, Eggerton KP, Scott SV, Kim J, Fischer AM, Klionsky DJ. (2001). Degradation of lipid vesicles in the yeast vacuole requires function of Cvt17, a putative lipase. J Biol Chem , 2083–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumm M. (2000). Structure and function of the yeast vacuole and its role in autophagy. Microsc Res Tech , 563–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada M, Ohsumi Y. (1993). Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett , 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Hazel HB, Kielland-Brandt MC, Winther JR. (1996). Review: biosynthesis and function of yeast vacuolar proteases. Yeast , 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther JR, Stevens TH, Kielland-Brandt MC. (1991). Yeast carboxypeptidase Y requires glycosylation for efficient intracellular transport, but not for vacuolar sorting, in vivo stability, or activity. Eur J Biochem , 681–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wünschmann J, Beck A, Meyer L, Letzel T, Grill E, Lendzian KJ. (2007). Phytochelatins are synthesized by two vacuolar serine carboxypeptidases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett , 1681–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Huang J, Geng J, Nair U, Klionsky DJ. (2006). Atg22 recycles amino acids to link the degradative and recycling functions of autophagy. Mol Biol Cell , 5094–5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorimitsu T, Zaman S, Broach JR, Klionsky DJ. (2007). Protein kinase A and Sch9 cooperatively regulate induction of autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell , 4180–4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Baumann U, Reymond JL. (2004). An efficient one-step site-directed and site-saturation mutagenesis protocol. Nucleic Acids Res , e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.