Abstract

In the winter of 2014/15 a novel GII.P17-GII.17 norovirus strain (GII.17 Kawasaki 2014) emerged, as a major cause of gastroenteritis outbreaks in China and Japan. Since their emergence these novel GII.P17-GII.17 viruses have replaced the previously dominant GII.4 genotype Sydney 2012 variant in some areas in Asia but were only detected in a limited number of cases on other continents. This perspective provides an overview of the available information on GII.17 viruses in order to gain insight in the viral and host characteristics of this norovirus genotype. We further discuss the emergence of this novel GII.P17-GII.17 norovirus in context of current knowledge on the epidemiology of noroviruses. It remains to be seen if the currently dominant norovirus strain GII.4 Sydney 2012 will be replaced in other parts of the world. Nevertheless, the public health community and surveillance systems need to be prepared in case of a potential increase of norovirus activity in the next seasons caused by this novel GII.P17-GII.17 norovirus.

In this issue of Eurosurveillance, observations from Japan are reported on an unusual prevalence of a previously rare norovirus genotype, GII.17, in diarrheal disease outbreaks at the end of the 2014/15 winter season [1], similar to what was observed for China [2,3]. Norovirus is a leading cause of gastroenteritis [4]. Although the infection is self-limiting in healthy individuals, clinical symptoms are much more severe and can last longer in immunocompromised individuals, the elderly and young children [5,6].

The Norovirus genus comprises seven genogroups (G), which can be subdivided in more than 30 genotypes [7]. Viruses belonging to the GI, GII and GIV genogroups can infect humans, but since the mid-1990s GII.4 viruses have caused the majority (ca 70–80%) of all norovirus-associated gastroenteritis outbreaks worldwide [8–10].

GII.4 viruses can continue to cause widespread disease in the human population because they evolve through accumulations of mutations into so-called drift variants that escape immunity from previous exposures [11]. Contemporary GII.4 noroviruses also demonstrate intra-genotype recombination near the junction of open reading frame (ORF) 1 and ORF2, which is likely to foster the emergence of novel GII.4 variants [12]. In addition, the binding properties of GII.4 viruses have altered over time, resulting in a larger susceptible host population [13].

Emergence and geographical spread of GII.17 genotype noroviruses

Viruses of the GII.17 genotype have been circulating in the human population for at least 37 years; the first GII.17 strain in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) databank is from 1978 [14]. Since then viruses with a GII.17 capsid genotype have sporadically been detected in Africa, Asia, Europe, North America and South America (Table, Figure 1). The virus appears to be clinically relevant, as it has been associated with acute gastroenteritis (AGE) in children and adults, and with chronic infection in an immunocompromised renal transplant patient [15] and a leukaemia patient (unpublished data). In the United States (US), only four GII.17 outbreaks were reported between 2009 to 2013 through CaliciNet, with a median of 11.5 people affected by each outbreak [16]. In Noronet, an informal international network of scientists working in public health institutes or universities sharing virological, epidemiological and molecular data on norovirus, GII.17 cases were also sporadically reported in Denmark and South Africa during this period [17].

Table.

Overview of detected GII.17 norovirus strains worldwide, 1978–2015

| Country | Geographical spread GII.17a |

Yearb | ORF1 | ORF2 | Study population | Proportions of typed strains or outbreaksc |

Suspected source of infection |

Description of the sequence (size) |

Accession number |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French Guiana | Single location | 1978 | GII.P4 | GII.17 | Children with AGE | 1 strain | – | Partial genome (7,441 bp) | KC597139, JN699043 | [14] |

| Brazil | Rio de Janeiro | 1997 (1994–2008) | – | GII.17 | Children with AGE | 3/52 strains | – | 5’-end ORF2 (300 bp) | JN600531 | [31] |

| Kenya | Nairobi | 1999–2000 | – | GII.17 | HIV positive children with or without AGE | 1/11 strains | – | 5’-end ORF2 (309 bp) | KF279387 | [32] |

| France | Briançon | 2004 | GII.P13 | GII.17 | Child with AGE | 1 strain | – | Partial ORF1/2 (1,361 bp) | EF529741 | Data not shown |

| Paraguay | Asuncion | 2004–2005 | – | GII.17 | AGE in children (<5 years) | 5/29 strains | – | 3’-end ORF2 (255 bp) | KC736582, KC736580, KC736578, KC736569 | [33] |

| Brazil | States of Acre (Brazil) | 2005 (2005–2009) | – | GII.17 | AGE | 2/62 strains | – | 3’-end ORF2 (215 bp) | JN587118 JN587117 | [34] |

| United States | Houston | 2005 | – | GII.17 | AGE evacuees hurricane Katrina | Predominant genotype in an outbreak | Sewage | ORF2 and 3 (2,459 bp) | DQ438972 | [35] |

| Argentina | Single location (Argentina) | 2005–2006 | – | GII.17 | River samples | 1/33 strains | – | – | – | [36] |

| Brazil | State of Rio de Janeiro | 2005–2006 (2004–2011) | – | GII.17 | Outbreaks of AGE | 3/112 outbreaks | – | 3’-end ORF2 (214 bp) | KJ179752, KJ179753, KJ179754 | [37] |

| Nicaragua | Léon | 2005–2006 | – | GII.17 | AGE | 1 strain | – | 5’-end ORF2 (244 bp) | EU780764 | [26] |

| France | Sommières | 2006 | GII.P13 | GII.17 | AGE | 1 strain | Foodborne | Partial ORF1/2 (1,056 bp) | EF529742 | Data not shown |

| Thailand | Lopburi | 2006–2007 | – | GII.17 | AGE | 2 strains | – | 5’-end ORF2 (209 bp) | GQ325666, GQ325670, | [38] |

| China | Wuhan | 2007 (2007–2010) | GII.P13 | GII.17 | AGE | 1/488 strains | – | Partial ORF1/2 (1,096 bp) | JQ751044 | [39] |

| Mexico | Mexico City | 2007 | – | GiI.17 | – | – | Waterborne | 5’-end ORF2 (1,337 bp) | JF970609 | NCBId |

| Switzerland | Zürich | 2008 | – | GII.17 | Renal transplant patient | 1/9 strains | – | ORF2 (1,599 bp) | GQ266696 | [15] |

| Nicaragua | Léon | 2008 | – | GII.17 | AGE in children (<5 years) | 2/38 strains | – | 5’-end ORF2 (244 bp) | EU780764 | [40] |

| South Korea | Seoul | 2010 (2008–2011) | – | GII.17 | AGE | 1/710 strains | – | 5’-end ORF2 (209) | JQ944348 | [41] |

| Brazil | Quilombola | 2009 (2008–2010) | – | GII.17 | Children (<10 years) | 2/16 strains | – | 3’-end ORF2 (215 bp) | JX047021, JX047022 | [42] |

| Cameroon | Southwestern region of Cameroon | 2009 | GII.P13 | GII.17 | Healthy children and HIV positive adults | 4/15 strains | – | Partials ORF1/2 (1,024 bp) | JF802504–JF802507 | [43] |

| Guatemala | Tecpan | 2009 | – | GII.17 | Children after waterborne outbreak | 1/18 strains | Waterborne | – | – | [44] |

| Burkina Faso | Ouagadougou | 2009–2010 | – | GII.17 | AGE in children (<5 years) | 1/36 strains | – | 5’-end ORF2 (287 bp) | JX416405 | [27] |

| Netherlands | Single location | 2002–2007 | – | GII.17 | Nosocomial | 3/264 strains | Nosocomial | – | – | [45] |

| South Korea | South Korea | 2010 | – | GII.17 | Groundwater samples | 2/7 strains | – | 5’-end ORF2 (311 bp) | KC915021–KC915022 | [18] |

| Ireland | Ireland | 2010 | – | GII.17 | Influent waste water | 4/24 strains | – | 5’-end (302 bp) | JQ362530 | [46] |

| South Africa | South Africa | 2010–2011 | – | GII.17 | Waste water | 9/69 strains | – | 5’-end ORF2 (305 bp) | KC495680, KC495686, KC495672–KC495674, KC495664, KC495657, KC495655, KC495640 | [47] |

| South Korea | Jinhae Bay | 2010–2011 | – | GII.17 | Oysters | 1 strain | – | – | – | [48] |

| Morocco | Oujda (Morocco) | 2011 | – | GII.17 | AGE in children (<5 years) | 1/42 strains | – | 5’-end (205 bp) | KJ162374 | [49] |

| South Africa | Johannesburg (South Africa) | 2011 | GII.P16 | GII.17 | AGE | – | Partial ORF1/2 (1,010 bp) | KC962460 | [50] | |

| Cameroon | Limbe | 2011–2012 | GII.P3 | GII.17 | Healthy adults and Children | 4/100 strains | – | Partial ORF1/2 (653 bp) | KJ946403 | [51] |

| Kenya | Kenya | 2012–2013 | – | GII.17 | Surface water | 16/21 strains | – | 5’-end ORF2 (306 bp) | KF916584–KF916585, KF808227–KF808254 | [19] |

| South Korea | Gyeonggi | 2012 | – | GII.17 | AGE outbreak | 1 strain | Waterborne | 5’-end (205 bp) | KC413386 KC413399–KC413403 | [22] |

| China | Guangdong province | 2014–2015 | – | GII.17 | AGE outbreaks | 24/29 outbreaks | – | 5’-end (249 bp) | KP718638–KP718738 | [3] |

| United States | Gaithersburg | 2014 | GII.P17 | GII.17 | AGE in child of 3 years | 1 strain | – | Partial genome (7,527 bp) | KR083017 | [21] |

| China | Jiangsu province | 2014–2015 | GII.P17 | GII.17 | Outbreaks of AGE | 16/23 outbreaks | – | – | KR270442–KR270449 | [2] |

| Japan | Japan | 2014–2015 | GII.P17 | GII.17 | Outbreaks of AGE | 100/2,133 strains | – | Partial genome (7,534–7,555 bp) | AB983218, LC037415, LC043139, LC043167, LC043168, LC043305 | [1] |

AGE: acute gastroenteritis; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; NCBI: National Center for Biotechnology Information; ORF: open reading frame.

GII.17 detection location with study location between brackets (when different from GII.17 detection location).

GII.17 detection year(s) with study years between brackets.

Either the proportion of strains that was typed as GII.17 or the proportion of outbreaks that was caused by GII.17 is given.

Information derived from the GenBank entry related to the accession number of the sequence.

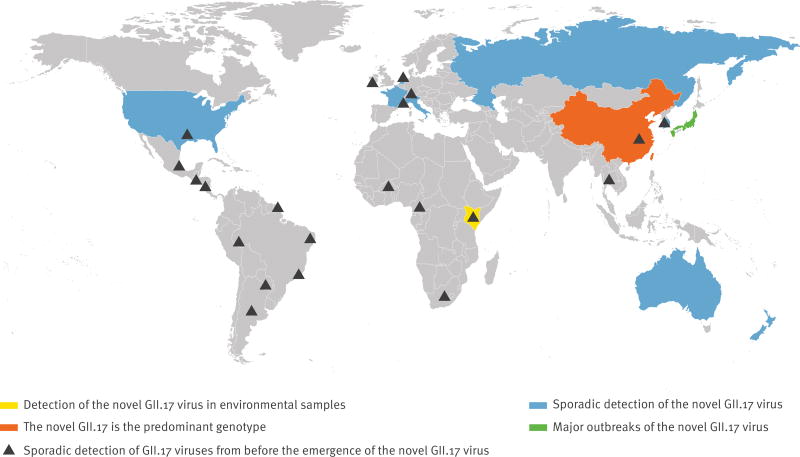

Figure 1.

World map showing areas where GII.17 norovirus strains have been detected, 1978–2015

More widespread circulation of GII.17 was first reported for environmental samples in Korea from 2004 to 2006. This information was published in a report in 2010 by the Korean Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) and was cited by Lee et al. [18], but the original document describing this finding is not publicly available and there are no matching clinical reports. From 2012 to 2013 a novel GII.17 virus accounted for 76% of all detected norovirus strains in rivers in rural and urban areas in Kenya [19]. In the winter of 2014/15, genetically closely related GII.17 viruses were first detected in AGE outbreaks in the Guangdong province in China in schools, colleges, factories and kindergartens [3]. Sequence analyses demonstrated that 24 of the 29 reported outbreaks during that winter were caused by GII.17. A large increase in the incidence of AGE outbreaks was also reported; 29 outbreaks associated with 2,340 cases compared with nine outbreaks and 949 cases in the previous winter when GII.4 Sydney 2012 still was the dominant genotype [3].

During the same winter there was also an increase in outbreak activity in Jiangsu province, which could be attributed to the emergence of this novel GII.17 [2]. This triggered us to investigate the prevalence of GII.17 in other parts of the world by means of a literature study and by inviting researchers collaborating within Noronet to share their data on GII.17. Currently, in Asia, in addition to Guangdong and Jiangsu [2,3], the novel GII.17 is also the predominant genotype in Hong Kong (unpublished data) and Taiwan [20], while in Japan, a sharp increase in the number of cases caused by this novel virus has been observed during the 2014/15 winter season [1]. Related viruses have been detected sporadically in the US [21] (http://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/reporting/calicinet/index.html), Australia, France, Italy, Netherlands, New-Zealand and Russia (unpublished data, www.noronet.nl) (Figure 1). In France the novel GII.17 virus appeared at the beginning of 2013, but since then, it has not resulted in an increase in AGE outbreaks as observed in China, nor replaced the predominant GII.4 in the last seasons (data not shown).

Based on sequence analyses of the ORF1–ORF2 junction region, most diagnostic real-time transcription polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) will be able to detect this novel GII.17 virus, but it is not known whether the same holds true for immunoassays. However, only a small portion of norovirus outbreaks are typed beyond the GI and GII classification, therefore it is possible that GII.17 is more prevalent than we currently suspect.

Phylogenetic analyses and molecular characterisation of the novel GII.17 viruses

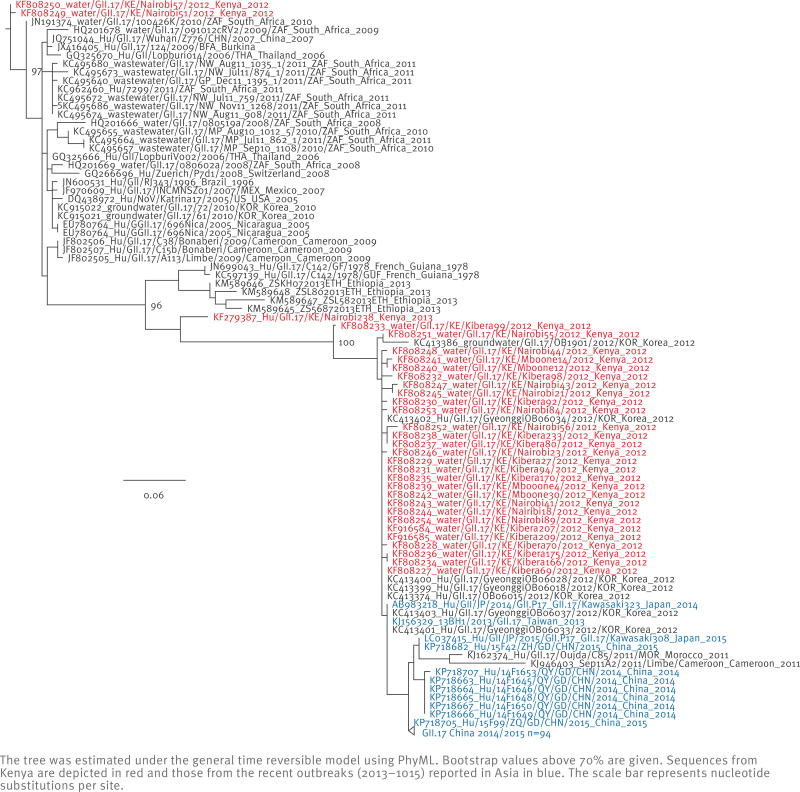

Phylogenetic analysis of the viral protein 1 (VP1) of GII.17 strains in the NCBI database demonstrated at least two clusters, with the novel Asian GII.17 strains grouping together with the GII.17 strains detected in the surface water in Kenya (Figure 2,[21]) and in an outbreak in 2012 in Korea [22]. Although the novel GII.17 clusters away from previously identified GII.17 strains, the amino acids changes in VP1 are not sufficient to separate it into a different genotype. For only a limited number of GII.17 strains the full VP1 has been sequenced, which demonstrated three deletions and at least one insertion compared with previous GII.17 strains (comprehensive alignments are given in Fu et al. and Parra et al. [2,21]). The majority of these changes could be mapped in or near major epitopes of the VP1 protein and potentially result in antigenic drift or altered receptor-binding properties [21]. Most publicly available GII.17 sequences only comprise the VP1, and most frequently the 5’-end of VP1 (C region), while most of the observed diversity within the GII.17 genotype is observed in the 3’-end of VP1 (D region) [23].

Figure 2.

Unrooted maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the 5’-end of virus protein 1 (VP1) sequences (C region) of GII.17 noroviruses, available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)

The tree was estimated under the general time reversible model using PhyML. Bootstrap values above 70% are given. Sequences from Kenya are depicted in red and those from the recent outbreaks (2013–1015) reported in Asia in blue. The scale bar represents nucleotide substitutions per site.

Previously, viruses with a GII.17 VP1 genotype contained a GII.P13 ORF1 genotype, although recombinants with an ORF1 GII.P16, GII.P3 and GII.P4 genotype have also been identified (Table). Sequence comparison showed that the ORF1 region of the novel GII.17 viruses was not detected before and cluster between GII.P3 and GII.P13 viruses [21]. Since this is the first orphan ORF1 sequence associated with GII.17, it has been designated GII.P17 according to the criteria of the proposal for a unified norovirus nomenclature and genotyping [24]. The novel GII.17 virus was termed Kawasaki 2014 after the first near complete genome sequence (AB983218) submitted to GenBank. Noronet provides a publicly available and widely used tool for the typing of norovirus sequences (http://www.rivm.nl/mpf/norovirus/typingtool). This typing tool was updated to ensure correct classification of both ORF1 and ORF2 sequences of the newly emerged GII.P17-GII.17 viruses.

The acquisition of a novel ORF1 could potentially result in an increase in replication efficiency and may – in part – explain the increase of the AGE outbreak activity. Histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs) function as (co-) receptors for noroviruses. Alpha(1,2)fucosyltransferase 2 (FUT2) adds an alpha-1,2 linked fucose on HBGAs, and individuals lacking the FUT2 gene are referred to as ‘non-secretors’, while those with a functional FUT2 gene are called ‘secretors’. Non-secretors have been shown to be less susceptible to infection with several norovirus genotypes [25]. In studies investigating the genetic susceptibility to norovirus genotypes, a secretor patient with blood type O Lewis phenotype Lea–b + and a secretor patient with blood type B Lewis phenotype Lea–b− were positive for previously identified GII.17 viruses and no non-secretors were found positive [26,27], suggesting that there could be genetic restrictions for GII.17 viruses in infection of humans. How the observed genetic changes have affected the antigenic and binding properties of the novel GII.17 strains, and hereby the susceptible host population, remains to be discovered.

Public health implications

Based on the emergence and spread of new GII.4 variants, we know that noroviruses are able to rapidly spread around the globe [28,29]. The novel GII.17 virus has been detected in sporadic cases throughout the world, but until now it has not resulted in an increase in outbreak activity or replacement of GII.4 Sydney 2012 viruses outside of Asia. Following the patterns observed in the past years for GII.4 noroviruses and based on the data from China and Japan, an increase in norovirus outbreak activity can be expected if the currently dominant GII.4 is replaced by GII.17. Another possibility – however – would be some restriction to global expansion, as has been observed previously for the norovirus variant GII.4 Asia 2003 [29]. Such restrictions could be due to differences in pre-existing immunity, but could also be the result of differences between populations in the expression of norovirus receptors [29]. Based on current literature on the novel GII.17 virus there is no indication that it will be more virulent compared with GII.4. Nevertheless, the public health community and surveillance systems need to be prepared in case of a potential increase of norovirus activity by this novel GII.17 virus.

Conclusions

Understanding the epidemiology of norovirus genotypes is important given the development of vaccines that are entering clinical trials. Current candidate vaccines have targeted the most common norovirus genotypes, and it remains to be seen if vaccine immunity is cross-reactive with GII.17 viruses [30]. Contemporary norovirus diagnostic assays may not have been developed to detect genotype GII.17 viruses since this genotype was previously only rarely found during routine surveillance. These assays need to be evaluated and updated if necessary to correctly diagnose norovirus outbreaks caused by the emerging GII.17 virus. Norovirus strain typing ideally should include ORF1 sequences and the variable VP1 ‘D’ region as well as metadata on the host, like clinical symptoms, immune status and blood group. This will allow us to better study and monitor the genetic disposition, pathogenesis, evolution and epidemiology of this newly emerged virus.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the submitting laboratories of the sequences from the Noronet database. This work was supported by the EU H2020 grant COMPARE under grant agreement number 643476 and the Virgo Consortium, funded by Dutch government project number FES0908 and the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA/NKFIH K111615). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Authors’ contributions

MG, JB, HV: compiling the data, drafting the manuscript; AP, FB, KT, MC, JM, JN, GR, ML, LDR, NI JH, VM, KAB, JV, PW: collecting field data, critical review of the manuscript; MK: initiation of study, providing data, critical review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Matsushima Y, Ishikawa M, Shimizu T, Komane A, Kasuo S, Shinohara M, et al. Genetic analyses of GII.17 norovirus strains in diarrheal disease outbreaks from December 2014 to March 2015 in Japan reveal a novel polymerase sequence and amino acid substitutions in the capsid region. Euro Surveill. 2015;20(26) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.26.21173. pii=21173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu J, Ai J, Jin M, Jiang C, Zhang J, Shi C, et al. Emergence of a new GII.17 norovirus variant in patients with acute gastroenteritis in Jiangsu, China, September 2014 to March 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20(24):21157. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.24.21157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu J, Sun L, Fang L, Yang F, Mo Y, Lao J, et al. Gastroenteritis Outbreaks Caused by Norovirus GII.17, Guangdong Province, China, 2014–2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(7):1240–2. doi: 10.3201/eid2107.150226. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2107.150226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atmar RL, Estes MK. The epidemiologic and clinical importance of norovirus infection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35(2):275–90. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.03.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroneman A, Harris J, Vennema H, Duizer E, van Duynhoven Y, Gray J, et al. Data quality of 5 years of central norovirus outbreak reporting in the European Network for food-borne viruses. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30(1):82–90. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm080. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdm080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wikswo ME, Hall AJ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis transmitted by person-to-person contact--United States, 2009–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(9):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinjé J. Advances in laboratory methods for detection and typing of norovirus. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(2):373–81. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01535-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01535-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siebenga JJ, Lemey P, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Rambaut A, Vennema H, Koopmans M. Phylodynamic reconstruction reveals norovirus GII.4 epidemic expansions and their molecular determinants. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(5):e1000884. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000884. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopman B, Vennema H, Kohli E, Pothier P, Sanchez A, Negredo A, et al. Increase in viral gastroenteritis outbreaks in Europe and epidemic spread of new norovirus variant. Lancet. 2004;363(9410):682–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15641-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Beek J, Ambert-Balay K, Botteldoorn N, Eden JS, Fonager J, Hewitt J, et al. NoroNet. Indications for worldwide increased norovirus activity associated with emergence of a new variant of genotype II.4, late 2012. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(1):8–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindesmith LC, Beltramello M, Donaldson EF, Corti D, Swanstrom J, Debbink K, et al. Immunogenetic mechanisms driving norovirus GII.4 antigenic variation. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(5):e1002705. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eden JS, Tanaka MM, Boni MF, Rawlinson WD, White PA. Recombination within the pandemic norovirus GII.4 lineage. J Virol. 2013;87(11):6270–82. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03464-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.03464-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.L C, Donaldson EF, Lobue AD, Cannon JL, Zheng DP, Vinje J, et al. Mechanisms of GII.4 norovirus persistence in human populations. PLoS Med. 2008;5(2):e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050031. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rackoff LA, Bok K, Green KY, Kapikian AZ. Epidemiology and evolution of rotaviruses and noroviruses from an archival WHO Global Study in Children (1976–79) with implications for vaccine design. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e59394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059394. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schorn R, Höhne M, Meerbach A, Bossart W, Wüthrich RP, Schreier E, et al. Chronic norovirus infection after kidney transplantation: molecular evidence for immune-driven viral evolution. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(3):307–14. doi: 10.1086/653939. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/653939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vega E, Barclay L, Gregoricus N, Shirley SH, Lee D, Vinjé J. Genotypic and epidemiologic trends of norovirus outbreaks in the United States, 2009 to 2013. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(1):147–55. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02680-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02680-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhoef L, Hewitt J, Barclay L, Ahmed SM, Lake R, Hall AJ, et al. Norovirus genotype profiles associated with foodborne transmission, 1999–2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(4):592–9. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141073. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2104.141073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee BR, Lee SG, Park JH, Kim KY, Ryu SR, Rhee OJ, et al. Norovirus contamination levels in ground water treatment systems used for food-catering facilities in South Korea. Viruses. 2013;5(7):1646–54. doi: 10.3390/v5071646. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/v5071646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiulia NM, Mans J, Mwenda JM, Taylor MB. Norovirus GII.17 Predominates in Selected Surface Water Sources in Kenya. Food Environ Virol. 2014;6(4):221–31. doi: 10.1007/s12560-014-9160-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12560-014-9160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.TaipeiTimes. CDC probing strain of Taichung norovirus. 2015 Available from: http://wwwtaipeitimescom/News/taiwan/archives/2015/02/25/2003612208.

- 21.Parra IP, Green KY. Genome of Emerging Norovirus GII.17, United States, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(8) doi: 10.3201/eid2108.150652. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2108.150652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho HG, Lee SG, Kim WH, Lee JS, Park PH, Cheon DS, et al. Acute gastroenteritis outbreaks associated with ground-waterborne norovirus in South Korea during 2008–2012. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142(12):2604–9. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814000247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0950268814000247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinjé J, Hamidjaja RA, Sobsey MD. Development and application of a capsid VP1 (region D) based reverse transcription PCR assay for genotyping of genogroup I and II noroviruses. J Virol Methods. 2004;116(2):109–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2003.11.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroneman A, Vega E, Vennema H, Vinjé J, White PA, Hansman G, et al. Proposal for a unified norovirus nomenclature and genotyping. Arch Virol. 2013;158(10):2059–68. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1708-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00705-013-1708-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindesmith L, Moe C, Marionneau S, Ruvoen N, Jiang X, Lindblad L, et al. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nat Med. 2003;9(5):548–53. doi: 10.1038/nm860. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucardo F, Kindberg E, Paniagua M, Grahn A, Larson G, Vildevall M, et al. Genetic susceptibility to symptomatic norovirus infection in Nicaragua. J Med Virol. 2009;81(4):728–35. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.21426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nordgren J, Nitiema LW, Ouermi D, Simpore J, Svensson L. Host genetic factors affect susceptibility to norovirus infections in Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e69557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eden JS, Hewitt J, Lim KL, Boni MF, Merif J, Greening G, et al. The emergence and evolution of the novel epidemic norovirus GII.4 variant Sydney 2012. Virology. 2014;450–451:106–13. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.12.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siebenga JJ, Vennema H, Zheng DP, Vinjé J, Lee BE, Pang XL, et al. Norovirus illness is a global problem: emergence and spread of norovirus GII.4 variants, 2001–2007. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(5):802–12. doi: 10.1086/605127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/605127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernstein DI, Atmar RL, Lyon GM, Treanor JJ, Chen WH, Jiang X, et al. Norovirus vaccine against experimental human GII.4 virus illness: a challenge study in healthy adults. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(6):870–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu497. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiu497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferreira MS, Xavier MP, Tinga AC, Rose TL, Fumian TM, Fialho AM, et al. Assessment of gastroenteric viruses frequency in a children’s day care center in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil: a fifteen year study (1994–2008) PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e33754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033754. http://.dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mans J, Murray TY, Kiulia NM, Mwenda JM, Musoke RN, Taylor MB. Human caliciviruses detected in HIV-seropositive children in Kenya. J Med Virol. 2014;86(1):75–81. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23784. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.23784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galeano ME, Martinez M, Amarilla AA, Russomando G, Miagostovich MP, Parra GI, et al. Molecular epidemiology of norovirus strains in Paraguayan children during 2004–2005: description of a possible new GII.4 cluster. J Clin Virol. 2013;58(2):378–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.07.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fioretti JM, Ferreira MS, Victoria M, Vieira CB, Xavier MP, Leite JP, et al. Genetic diversity of noroviruses in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106(8):942–7. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000800008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762011000800008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yee EL, Palacio H, Atmar RL, Shah U, Kilborn C, Faul M, et al. Widespread outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis among evacuees of Hurricane Katrina residing in a large “megashelter” in Houston, Texas: lessons learned for prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(8):1032–9. doi: 10.1086/512195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/512195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernández MD, Torres C, Poma HR, Riviello-López G, Martínez LC, Cisterna DM, et al. Environmental surveillance of norovirus in Argentina revealed distinct viral diversity patterns, seasonality and spatio-temporal diffusion processes. Sci Total Environ. 2012;437:262–9. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.08.033. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Andrade JS, Rocha MS, Carvalho-Costa FA, Fioretti JM, Xavier MP, Nunes ZM, et al. Noroviruses associated with outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis in the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2004–2011. J Clin Virol. 2014;61(3):345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.08.024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kittigul L, Pombubpa K, Taweekate Y, Diraphat P, Sujirarat D, Khamrin P, et al. Norovirus GII-4 2006b variant circulating in patients with acute gastroenteritis in Thailand during a 2006–2007 study. J Med Virol. 2010;82(5):854–60. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21746. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.21746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang YH, Zhou DJ, Zhou X, Yang T, Ghosh S, Pang BB, et al. Molecular epidemiology of noroviruses in children and adults with acute gastroenteritis in Wuhan, China, 2007–2010. Arch Virol. 2012;157(12):2417–24. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1437-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00705-012-1437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bucardo F, Nordgren J, Carlsson B, Paniagua M, Lindgren PE, Espinoza F, et al. Pediatric norovirus diarrhea in Nicaragua. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(8):2573–80. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00505-08. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00505-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park S, Jung J, Oh S, Jung H, Oh Y, Cho S, et al. Characterization of norovirus infections in Seoul, Korea. Microbiol Immunol. 2012;56(10):700–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2012.00494.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1348-0421.2012.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aragão GC, Mascarenhas JD, Kaiano JH, de Lucena MS, Siqueira JA, Fumian TM, et al. Norovirus diversity in diarrheic children from an African-descendant settlement in Belém, Northern Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056608. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayukekbong J, Lindh M, Nenonen N, Tah F, Nkuo-Akenji T, Bergström T. Enteric viruses in healthy children in Cameroon: viral load and genotyping of norovirus strains. J Med Virol. 2011;83(12):2135–42. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.22243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arvelo W, Sosa SM, Juliao P, López MR, Estevéz A, López B, et al. Norovirus outbreak of probable waterborne transmission with high attack rate in a Guatemalan resort. J Clin Virol. 2012;55(1):8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.02.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sukhrie FH, Beersma MF, Wong A, van der Veer B, Vennema H, Bogerman J, et al. Using molecular epidemiology to trace transmission of nosocomial norovirus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(2):602–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01443-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01443-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajko-Nenow P, Waters A, Keaveney S, Flannery J, Tuite G, Coughlan S, et al. Norovirus genotypes present in oysters and in effluent from a wastewater treatment plant during the seasonal peak of infections in Ireland in 2010. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(8):2578–87. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03557-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03557-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murray TY, Mans J, Taylor MB. Human calicivirus diversity in wastewater in South Africa. J Appl Microbiol. 2013;114(6):1843–53. doi: 10.1111/jam.12167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jam.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sin SB, Oh EG, Yu H, Son KT, Lee HJ, Park JY, et al. Genetic diversity of Noroviruses detected in oysters in Jinhae Bay, Korea. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2013;22(5):1453–60. [Google Scholar]

- 49.El Qazoui M, Oumzil H, Baassi L, El Omari N, Sadki K, Amzazi S, et al. Rotavirus and norovirus infections among acute gastroenteritis children in Morocco. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):300. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mans J, Murray TY, Taylor MB. Novel norovirus recombinants detected in South Africa. Virol J. 2014;11(1):168. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-11-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ayukekbong JA, Fobisong C, Tah F, Lindh M, Nkuo-Akenji T, Bergström T. Pattern of circulation of norovirus GII strains during natural infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(12):4253–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01896-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01896-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]