Abstract

Purpose

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defines distress as a multifactorial, unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological nature that may interfere with patients’ ability to cope with cancer symptoms and treatment. Patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are at risk for distress given the largely incurable nature of this hematopoietic malignancy, and its symptom burden, yet associations with clinical outcomes are unknown.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed patient-reported distress data from ambulatory adult MDS patients visiting a single, tertiary care medical center from July 2013-September 2015. Demographic, diagnostic, treatment, and comorbidity information were abstracted from records along with the NCCN Distress Thermometer (DT) and Problem List (PL). Survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

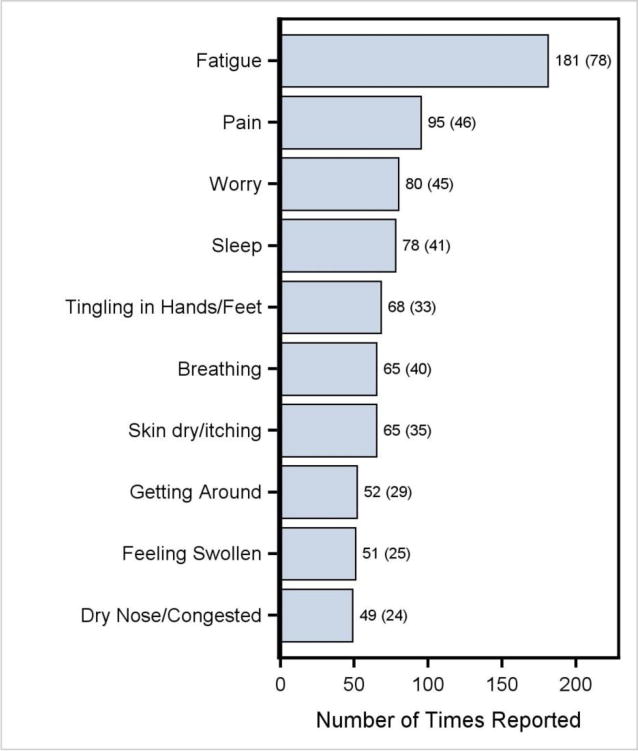

We abstracted 376 DT scores (median=1, range=0-10) from 606 visits and 110 patients (median=2 DT/patient, range=1-16). NCCN guidelines suggest DT >=4 should be evaluated for referral to specialty services to address unmet needs. Fifty-four patients (49%) had at least 1 DT >=4 and 20 (18%) had 2 or more DT >=4. Ninety-eight patients (89.1%) reported 1,379 problems during 23,613 person-days of follow-up (median=4 problems/patient/visit, range=1-23). The 5 most frequent were fatigue (181 times; 78 patients), pain (95 times; 46 patients), worry (80 times; 45 patients), sleep (78 times; 41 patients), and tingling hands/feet (68 times; 33 patients). After adjustment for risk stratification at diagnosis, a single point increase on the DT was associated with an increased risk of death (hazard ratio=1.18, 95% confidence interval: 1.01, 1.36).

Conclusion

MDS patients experience a high burden of distress, and patient-reported distress is associated with clinical outcomes. Distress should be further studied as a prognostic variable and a marker of unmet needs in MDS.

Keywords: myelodysplastic syndromes, patient reported outcome measures, quality of life, hematologic neoplasms, distress

Purpose

Being diagnosed and living with cancer can affect psychological and social wellbeing, interfere with tasks of daily living, reduce quality of life, and translate into physical health problems.1 These psychosocial complications of cancer are referred to as “distress.”2 Approximately 1/3rd of cancer patients experience distress.3 Distress may affect successful management of cancer through negatively impacting patients’ adherence to therapy and decision making capacity, and distress has been associated with reduced survival in some cancers.4–6

MDS are diagnosed primarily in older people and represent a diverse group of malignant bone marrow disorders with variable clinical outcome.7 Quality of life is substantially impacted by MDS.8 Distress is increased in cancer patients when comorbid conditions are present, when symptoms are uncontrolled, and when there are changes in disease status.2 Thus, distress is likely to be a concern with respect to clinical outcomes in MDS.

The DT has been used to measure distress in several tumor types but has not yet been applied to MDS. While MDS cases were included in studies describing distress in patients receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) these studies did not report results for MDS specifically.9–11 Furthermore, since HSCT is infrequently used in MDS, these results are not likely to be representative of distress levels in the broader MDS population.

To our knowledge there are no published data on distress in MDS patients receiving non-transplant therapies in an ambulatory care setting, where most MDS patients are managed. There is also reason to suspect that patient-reported distress might correlate with disease activity, given that it reflects how patients are feeling, perhaps beyond what is measurable in routine laboratory assessments (fatigue, for example, is known to correlate poorly with hemoglobin levels).12 Therefore, we conducted a retrospective evaluation of distress in patients with MDS. Our intent was to describe MDS patients’ magnitude and sources of distress, identify sources of distress, and explore associations with clinical outcomes.

Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were age >= 18 with pathologically confirmed MDS (International Classification of Diseases version 9 codes 238.72-5) and visited our tertiary care outpatient clinics between July 2013 and September 2015. The start date for this study reflects the date that our center began using a new electronic medical record (EMR) in which the DT and PL were entered as part of usual care. Patients were excluded if they received HSCT within 100 days of their first clinic visit during the data abstraction period.

Our initial search of the EMR identified 248 patients who were then screened. We excluded 124 (50%): 27 were vising our clinics for other malignancies, 21 had non-malignant diseases, 28 had MDS but visited our clinics for HSCT, 26 had a myeloproliferative neoplasm or an “overlap syndrome,” 11 had insufficient information to confirm an MDS diagnosis, and 11 patients had MDS but no record of a DT or PL.

Therefore, we abstracted data for 124 eligible patients who contributed a PL only (N=14), or both DT and PL (N=110). The study was reviewed and approved by our IRB, and a consent waiver was obtained prior to data abstraction.

Patient-Reported Distress

Distress is evaluated using the NCCN DT as part of routine care for all patients seen in the Duke Cancer Institute. The DT is a patient-reported screening tool that measures patients’ distress during the previous week using an 11-point Likert scale (0=no distress, 10=extreme distress) and is accompanied by a 39-item PL that allows patients to indicate the source of their distress in five different domains using Yes/No answers. The DT is a valid measure of distress, with a score of 4 identifying potentially actionable distress as described in NCCN algorithms for psychological/psychiatric treatment.13 At our center, MDS patients are asked to complete the DT and PL on paper at outpatient visits, and these data are transcribed into the EMR by clinic staff at the point of care. We abstracted data for eligible patients at any visit documented in the medical record during our study period.

Demographic, Disease, and Comorbidity Information

We abstracted the following from the EMR: age, sex, race, ethnicity, insurance status, marital status, cancer history, month/year of diagnosis, pathological subtype, and risk stratification at diagnosis. Patients were designated as Low, Intermediate, or High risk using the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) or IPSS-R (N=79) or the World Health Organization Prognostic Scoring System (N=45). We utilized both risk stratification schemas because many charts did not include all the necessary data elements to calculate risk by the IPSS/R. We evaluated the validity of this approach by comparing Kaplan-Meier survival curves across risk strata and observed the expected pattern of decreasing survival with increasing risk (not shown). The Charlson Comorbidity Index was used to describe comorbidities present at the time of diagnosis using data from the EMR.

Clinical Outcomes

Data on the following outcomes were abstracted, when available, from each clinical encounter: Karnofsky or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, current MDS therapy and newly added or changed therapy (hypomethylating agent, lenalidomide, growth factors, iron chelation, transfusions, other chemotherapy [e.g., induction therapy], and HSCT), blood counts, participation in a clinical trial, and progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Vital status was determined through review of the EMR and verified by our institution’s tumor registrar.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of our inferential analyses was to identify differences in the reporting of potentially actionable distress across a range of patient and disease characteristics. Thus, when patients reported more than one DT they were classified according to their maximum score. Number of observations was not associated with the maximum-reported DT (not shown). Non-parametric tests were used to compare DT between subgroups. Survival associated with DT was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Follow-up time was calculated from the date of enrollment in our study to the date of death or last visit during our study period. We also conducted stepwise, left-truncated Cox proportional hazards regression modeling to predict survival from time of diagnosis based on repeated measures of DT observed in our study. We considered as covariates only factors that we felt, based on previous research, might be associated with survival: age at diagnosis, use of therapy (hypomethylating agents/lenalidomide/growth factors/transfusions/chelation), Charlson comorbidity score, risk stratification at diagnosis, ever-report of fatigue, and frequency of fatigue. Analyses used SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Table 1 shows characteristics of the N=124 included patients. The median age at diagnosis was 69 years, most were white (74.2%) or male (66.9%), and 29.0% self-reported a prior history of cancer other than basal/squamous cell skin cancers (40 cancers reported among 36 patients). Approximately half (48.4%) had Low Risk disease and 5 patients (4%) progressed to AML. The predominant pathologic subtypes were refractory anemia with excess blasts (35.0%), refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia (34.1%), and refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts (13.0%). Healthcare encounters were generally uncommon (Figure 1). Only twenty-five (20.2%) had 1 or more hospitalizations and 12.1% visited the emergency department at least once. Among the 25 patients who died during out study period only 2 used hospice, and we did not find evidence of referral to palliative care clinics for any included patients.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| All Patients (N=124) |

|

|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis, years | |

| Mean (SD) | 67.8 (10.6) |

| Median (range) | 69.79 (30.68 – 88.18) |

| Months from Diagnosis to First Visit | |

| Mean (SD) | 21.1 (32.8) |

| Median (range) | 5.88 (0 – 206.7) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 83 (66.9%) |

| Female | 41 (33.1%) |

| Race | |

| White | 92 (74.2%) |

| Non-White | 11 (8.9%) |

| Unknown | 21 (16.9%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Not Married | 20 (16.1%) |

| Married | 84 (67.7%) |

| Unknown | 20 (16.1%) |

| Health Insurance | |

| Medicare | 87 (70.2%) |

| Medicaid | 3 (2.4%) |

| Private payer | 30 (24.2%) |

| Other | 4 (3.2%) |

| MDS Subtype | |

| Refractory anemia (RA) | 9 (7.3%) |

| Refractory cytopenia with unilineage dysplasia (RCUD) | 2 (1.6%) |

| Refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia (RCMD) | 42 (34.1%) |

| Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS) | 16 (13.0%) |

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts (RAEB) | 43 (35.0%) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome associated with del(5q) | 7 (5.7%) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome, unclassifiable | 3 (2.4%) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.8%) |

| Risk Stratificationa | |

| Low | 60 (48.4%) |

| Intermediate | 26 (21.0%) |

| High | 38 (30.6%) |

| Cancer History | |

| No | 88 (71.0%) |

| Yes | 36 (29.0%) |

| Died During Study Period | |

| Yes | 25 (20.2%) |

| No | 99 (79.8%) |

| Progressed to AML | |

| No | 119 (96.0%) |

| Yes | 5 (4.0%) |

Risk stratification is based on the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) or IPSS-R where available. For patients with unknown IPSS/R (N=45) the World Health Organization Prognostic Scoring System (WPSS) was used based on information obtained from the diagnosis visit.

Figure 1.

Healthcare Utilization

Patient-Reported Distress

We abstracted 376 DT (median distress=1, interquartile range [IQR]: 0-3.5, range: 0-10) from 606 visits and 110 patients (median=2 DT/patient, IQR: 1-4, range:1-16). Fifty-four patients had at least 1 DT >=4 and 20 had 2 or more DT >=4. When patients were classified by their maximum DT (median=3, IQR: 1-7, range: 0-10), ever-use of therapy was associated with greater maximum distress (N=75, median=4, IQR: 1-8, range=0-10) compared with no therapy (N=35, median=2, IQR: 1-4, range: 0-9; P=0.01). Ever-use of hypomethylating agents (P=0.75) or lenalidomide (P=0.09) was not associated with distress. However, use of growth factors was associated with higher maximum distress (N=32, median=5.5, IQR: 2-8, range: 0-10) than never use of growth factors (N=78, median=2.5, IQR: 1-6, range:0-10) (P=0.02). Receipt of red blood cells was associated with higher maximum distress (N=54, median=4.5, IQR: 1-8, range: 0-10) compared with never receiving packed red cells (N=56, median=2.5, IQR: 1-5, range: 0-10) (P=0.03). Patients who received platelets reported higher maximum distress (N=22, median=6, IQR: 3-8, range: 0-10) compared with patients who did not receive platelets (N=88, median=2.5, IQR: 1-6, range: 0-10); this difference approached statistical significance (P=0.06). Iron chelation was unrelated to distress although very few patients in our cohort were chelated (N=6; P=0.98). The number of visits that patients used each of these therapies was not related to the maximum reported DT. Finally, we did not observe any association between the maximum-reported DT and age at diagnosis, sex, race, marital status, type of health insurance, prior history of cancer, Charlson comorbidity index, the number of visits per patient during the study period, MDS subtype, risk stratification at diagnosis, being hospitalized, or visiting the emergency department (P > 0.05 for all).

Sources of Distress

The most frequently reported categories of problems were Physical (233 reports), Emotional (104 reports), Practical (49 reports), and Family (41 reports). Spiritual Problems were reported only once during the study. Within each of these categories, the number of problems reported per patient was not strongly associated with DT scores.

We analyzed the association between the DT and PL in the 110 patients who reported both. Ninety-eight of these patients (89.1%) reported 1,379 problems during 23,613 person-days of follow-up (median=4 problems/patient/visit, range=1-23). The 5 most frequent problems were fatigue (181 times; 78 patients), pain (95 times; 46 patients), worry (80 times; 45 patients), sleep (78 times; 41 patients), and tingling hands/feet (68 times; 33 patients) (Figure 2). The total number of problems reported per patient was significantly correlated with the maximum distress level reported by each patient (rSpearman = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.59-0.78, P < .0001).

Figure 2. Top Ten Most Frequently Reported Problems.

Numbers are: number of reports (number of patients).

Patient-Reported Distress and Survival

A maximum-reported DT >= 4 was associated with poor survival in our Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 3; p=0.01). Median time to death in patients with DT < 4 was 9.9 months (range: 3.8-22.0; 5 deaths) compared with a median of 5.1 months (range: 0.5-20.8) in patients reporting a maximum DT >= 4 (16 deaths). Cox proportional hazards regression models showed the DT, prognostic strata at diagnosis, and ever use of therapy to be significant predictors of death (Table 2). Only the DT and prognostic score remained significant after backward elimination. In the final model, each additional point on the DT scale was associated with an 18% increase in risk of death (95% CI: 1.01-1.36) after controlling for risk stratification at diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Overall Survival by Maximum Reported Distress

Table 2.

Results of Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Modeling

| Covariate | AIC w/Covariates | AIC Changed | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable Models | ||||

| Distress Thermometera | 97.38 | −9.56 | 1.28 (1.11, 1.47) | <.001 |

| Age at Diagnosisa | 106.70 | −0.24 | 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) | 0.135 |

| Risk Stratification at Diagnosisb | 96.24 | −10.70 | 6.92 (2.30, 20.79) | <.001 |

| Charlson Scorea | 107.34 | 0.40 | 1.18 (0.93, 1.48) | 0.206 |

| Ever Use of Therapyc | 104.48 | −2.46 | 3.99 (0.89, 17.87) | 0.035 |

| Ever Reported Fatiguec | 108.27 | 1.33 | 1.58 (0.51, 4.91) | 0.414 |

| Frequency of Fatiguea | 107.46 | 0.52 | 0.89 (0.73, 1.09) | 0.224 |

| Final Model | ||||

| Distress Thermometera | 93.53 | -13.41 | 1.18 (1.01, 1.36) | 0.030 |

| Risk Stratification at Diagnosisb | 4.02 (1.26, 12.83) | 0.016 | ||

AIC=Akaike information criteria. HR=hazard ratio. CI=confidence interval

Single point increase.

High vs. Intermediate/Low.

Yes vs. No.

AIC change is calculated from the AIC of the model without covariates, 106.94.

Conclusion

We observed 3 important findings in this retrospective cohort study of patient-reported distress in ambulatory MDS patients visiting a comprehensive cancer center. First, these patients have a relatively high burden of distress, with physical symptoms representing the most frequently-reported issue, and a greater overall symptom burden in these patients was associated with higher distress. Second, distress is associated more with the receipt of treatments and services, like blood transfusions, rather than with MDS prognosis, demographic variables, or comorbidities. Lastly, distress scores also appear to be related to overall survival, even after controlling for MDS prognosis.

Patients in our cohort were markedly distressed. We found that 54 of 110 patients (49%) had at least one DT score of 4 during the study period. However, the median DT across all patients and visits in our study was 1, and covered the entire range of the scale from 0 to 10. This suggests that MDS patients are not consistently distressed, but have a high probability of experiencing at least one clinical encounter characterized by marked distress and unmet needs in the course of a year or two of observation. We did not find other studies of distress in cancer with longitudinal evaluations of distress for direct comparison. However, we noted one study that estimated 33% of patients with cancer experience DT >= 4 prior to their first outpatient appointment with an oncologist.14 This is similar to the rate of 35% among members of our MDS cohort who had a DT within 60 days after diagnosis.

Our results suggest MDS patients’ needs are related to physical symptoms, particularly fatigue and pain, as well as psychological issues like worry. These sources of distress mirror the results of a large survey, which reflected a marked prevalence of fatigue and other physical symptoms in MDS including bruising, night sweats, and bone pain.15 However, there may be differences between the prevalence of symptoms and their contribution to distress. For example, many patients with MDS report bruising in symptom surveys,15 but this does not mean that bruising is necessarily a distressing symptom for most patients. The distinction between symptom prevalence and contribution to distress has implications for the identification of unmet needs and development of interventions to improve MDS patients’ experiences.

We observed that report of problems in specific areas (e.g., Physical Problems) was not associated with the maximum distress level. However, the total number of problems reported was associated with maximum-reported DT. This suggests that the overall burden of problems, rather than problems in any specific area, is most important. It is also worth noting that despite the burden of problems reported in our study, we found no evidence in the medical record of referrals to palliative care services although these services were available at our center during the study period. This observation is consistent with the general under-use of palliative care services that has been noted in hematologic malignancies relative to solid tumor cancers.16 Literature on the use of palliative care services in MDS is scant. A recent review suggested possible reasons for the divide between palliative care needs and medical practice in MDS may include clinical features of MDS that complicate recognizing end stage disease, misunderstanding of the intent or appropriateness of palliative care by hematologists in general, or misunderstanding of the efficacy of treatment for MDS by both patients and clinicians.17

We also found an association between patients’ receipt of certain services and their overall level of distress. For example, those receiving blood or platelet transfusions were more distressed than others. Interestingly, however, we did not find such associations with MDS risk scores, or other traditional variables associated with clinical outcomes, like age, or comorbidities. These results suggest that patient-reported distress is most closely associated with patients’ encounters with (and use of) the healthcare system, rather than with classical predictors of risk in MDS. This implies that patient-reported distress adds meaningful information not reflected in traditional clinical variables. The specificity of this finding argues against the possibility of bias arising from the study design, e.g., that patients receiving transfusions simply had more frequent visits and thus more opportunities to report distress. In that eventuality we would expect to have seen an association between distress and chemotherapy but we did not find this. Therefore, patient-reported distress should be studied further as a potential signal for unmet needs or as a prognostic variable.

Finally, using serial measures of distress in our cohort we observed that greater distress, regardless of when it is reported during routine clinical follow-up, is associated with increased risk of death even after controlling for the most important prognostic factor in MDS: risk score. This interesting finding adds to the literature suggesting that patient-reported symptom data offers important prognostic information beyond traditional clinical data, such as the recent description of fatigue as an independent predictor of survival in MDS.18 Our study was limited in its ability to explore this finding further due to the small number of deaths in our cohort. A larger, multi-site investigation of this association is warranted.

The primary limitation of our study is its retrospective nature. In particular, the number of visits per patient and the elapsed time between visits were determined by each patient’s medical needs, rather than per-protocol. Therefore, while our study included longitudinal assessment of distress, our cohort was not measured from a common baseline. However, we were able to leverage the longitudinal data for estimating the association of distress with survival using well-established statistical methods. Also, we did not validate DT findings against other measures such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as has been done in other tumor types. Nonetheless, ~1/2 of patients in our study reported DT greater than or equal to the NCCN-defined threshold of 4, and reporting a maximum DT at this level was associated with use of several disease-specific therapies, offering some face validity for the NCCN-defined distress threshold in MDS.

Despite these limitations, our study offers what we believe to be the first inventory of distress in MDS patients regularly attending an outpatient clinic. Given that most MDS patients are ambulatory, our study likely represents the usual clinical experience in MDS. Most importantly, our study demonstrates the ability of the NCCN DT to measure distress in MDS patients, and that these distress levels may have deleterious effects on aspects of constitutional and social health. Therefore, our results indicate the DT is a potential screening tool for identifying MDS patients who require intervention. This observation is well-timed given the recent development of MDS-specific quality of life (QOL) measures that might be used as endpoints in studies examining the efficacy of interventions for improving QOL in MDS.19

In summary, distress is measurable in ambulatory MDS patients using the NCCN DT; distress is common in MDS and is associated with physical, emotional, and social problems; distress may be exacerbated by use of MDS-specific therapies; and distress is potentially associated with survival. Future studies should evaluate the efficacy of interventions to improve distress and ameliorate patient-reported problems in MDS.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Palliative Care Research Cooperative, number 2015-01p and U24NR014637.

References

- 1.VanHoose L, Black LL, Doty K, et al. An analysis of the distress thermometer problem list and distress in patients with cancer. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2471-1. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland JC. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Distress Management Version 2.2017. 2017 https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/distress.pdf. Accessed September 8, 2017, 2017.

- 3.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-oncology. 2001;10(1):19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):602–606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown KW, Levy AR, Rosberger Z, Edgar L. Psychological distress and cancer survival: a follow-up 10 years after diagnosis. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):636–643. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000077503.96903.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L, et al. Depression and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: effects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(12):1310–1315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Troy JD, Atallah E, Geyer JT, Saber W. Myelodysplastic Syndromes in the United States: An Update for Clinicians. Annals of Medicine. 46(5):283–289. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.898863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heptinstall K. Quality of life in myelodysplastic syndromes. A special report from the Myelodysplastic Syndromes Foundation, Inc. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 2008;22(2 Suppl):13–18. Nurse Ed. discussion 19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bevans M, Wehrlen L, Prachenko O, Soeken K, Zabora J, Wallen GR. Distress screening in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSCT) caregivers and patients. Psycho-oncology. 2011;20(6):615–622. doi: 10.1002/pon.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braamse AM, van Meijel B, Visser O, Huijgens PC, Beekman AT, Dekker J. Distress, problems and supportive care needs of patients treated with auto- or allo-SCT. Bone marrow transplantation. 2014;49(2):292–298. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ransom S, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M. Validation of the Distress Thermometer with bone marrow transplant patients. Psycho-oncology. 2006;15(7):604–612. doi: 10.1002/pon.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efficace F, Gaidano G, Breccia M, et al. Prevalence, severity and correlates of fatigue in newly diagnosed patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2015;168(3):361–370. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, et al. Distress management. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2013;11(2):190–209. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kendall J, Glaze K, Oakland S, Hansen J, Parry C. What do 1281 distress screeners tell us about cancer patients in a community cancer center? Psycho-oncology. 2011;20(6):594–600. doi: 10.1002/pon.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steensma DP, Heptinstall KV, Johnson VM, et al. Common troublesome symptoms and their impact on quality of life in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS): results of a large internet-based survey. Leuk Res. 2008;32(5):691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeBlanc TW. Addressing End-of-Life Quality Gaps in Hematologic Cancers: The Importance of Early Concurrent Palliative Care. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):265–266. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nickolich M, El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc TW. Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11(6):434–440. doi: 10.1007/s11899-016-0352-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Efficace F, Gaidano G, Breccia M, et al. Prognostic value of self-reported fatigue on overall survival in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: a multicentre, prospective, observational, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(15):1506–1514. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abel GA, Efficace F, Buckstein RJ, et al. Prospective international validation of the Quality of Life in Myelodysplasia Scale (QUALMS) Haematologica. 2016;101(6):781–788. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.140335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]