Abstract

The Trump administration has undertaken an assault on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), an agency critical to environmental health. This assault has precedents in the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush. The early Reagan administration (1981–1983) launched an overt attack on the EPA, combining deregulation with budget and staff cuts, whereas the George W. Bush administration (2001–2008) adopted a subtler approach, undermining science-based policy. The current administration combines both these strategies and operates in a political context more favorable to its designs on the EPA. The Republican Party has shifted right and now controls the executive branch and both chambers of Congress. Wealthy donors, think tanks, and fossil fuel and chemical industries have become more influential in pushing deregulation. Among the public, political polarization has increased, the environment has become a partisan issue, and science and the mainstream media are distrusted. For these reasons, the effects of today’s ongoing regulatory delays, rollbacks, and staff cuts may well surpass those of the administrations of Reagan and Bush, whose impacts on environmental health were considerable.

In less than a year, the Trump administration has overturned or delayed dozens of regulations of, proposed massive budget cuts for, and reduced staff and enforcement at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as part of a broad challenge to existing US environmental health policy. This approach is not without historical precedent. Comparison with similar initiatives during the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush sheds light on the roots of the Trump assault, while clarifying what is new about it. The early Reagan administration (1981–1983) launched an overt attack on the EPA, combining deregulation with budget and staff cuts, whereas the George W. Bush administration (2001–2008) adopted a subtler approach, undermining science-based policy. The Trump administration combines both these strategies. It also operates in an institutional and cultural context that is more favorable to the new administration’s designs on an agency critical to the nation’s environmental health. In this history, we suggest a difficult period ahead and offer hope for sustaining this agency’s role in protecting environmental health.

We focus on the EPA because the Trump administration has targeted it and because the EPA is the primary federal regulator of environmental health. Other agencies also deal with environmental health, but less centrally, and many do not make and enforce regulations. None produces as many regulations with as many environmental health benefits as the EPA.1 We used secondary sources, newspapers, government documents, and 54 interviews with current and former EPA employees conducted by the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI). EDGI identified interviewees through preexisting relationships, responses to an alumni association invitation, and snowball sampling. Approximately half had or still worked primarily at the District of Columbia headquarters, two fifths at regional offices, and the rest split time between headquarters and regions. Interviewees worked across a broad range of agency offices and had a range of professional backgrounds. Our questions concerned presidential transitions, workplace morale, and the politics of science and policy in the agency.2

Attacks on the EPA are especially concerning because of the strong connection between the agency’s activities and public health. The EPA’s hazardous waste, drinking water, and air pollution regulations have reduced many health problems, including cancer, reproductive problems, fetal toxicity, lowered IQ, heart attacks, asthma, and numerous other cardiovascular, respiratory, and chronic health conditions. From air pollution control alone, economists have estimated enormous benefits over time, including an estimated $50 to $400 billion in benefits between 1970 and 2000 and $2 trillion in benefits since 1990.3

Despite these benefits, the new administration is convinced that the EPA needs to be brought to heel. Current conditions favor its resolve in ways that those in earlier decades did not. The Republican Party has shifted to the right and now controls the executive branch and both chambers of Congress (unlike in the early Reagan administration). Wealthy donors, think tanks, and fossil fuel and chemical industries have become more influential in fighting regulation. In the broader public, political polarization has increased, the environment has become a partisan issue, and science and the mainstream media are distrusted. For these reasons, the effects of today’s ongoing regulatory delays, rollbacks, and staff cuts may well surpass those of the administrations of Reagan and Bush, whose impacts on environmental health were considerable.

THE REAGAN ASSAULT

The EPA was created by an executive initiative of the Republican president Richard Nixon in 1970, the culmination of decades of rising environmental concern and growing dissatisfaction with absent or ineffective environmental regulation at the state level. President Nixon proposed a “strong, independent agency” with a “broad mandate” to control pollution, and a bipartisan Congress passed landmark acts for clean air (1970) and clean water (1972) that the new agency would enforce. Over the next few years these and other laws gave the new agency ambitious goals and powerful tools to set and enforce national pollution standards. But as this new agency pushed against private interests, and in some cases the prerogatives of state regulators, powerful resistance arose.4

New antienvironmental conservatives in the Republican Party found a champion in Ronald Reagan, who in 1980 won office through a campaign against government overreach by federal bureaucracies, including the EPA. As president-elect, he snubbed a moderate environmental policy blueprint drafted by Republican environmentalists in favor of a plan written by the Heritage Foundation, a right-wing think tank then less than a decade old, that devolved EPA functions and authority back to the states.5

Once in office, Reagan abandoned the practice of previous administrations of appointing agency heads with federal government experience and sympathy for the agency’s mission. Instead, he chose people from industry who shared his antiregulatory views. To run the EPA, Reagan selected Anne Gorsuch, a 38-year-old corporate lawyer and two-term Colorado legislator who had opposed the Clean Air Act, water quality rules, and hazardous waste protections.6 Other EPA appointments were also based more on ideology and loyalty than government experience, with many coming from the industries that they were tasked with regulating, including Aerojet General and Exxon.7

Gorsuch demoralized, marginalized, and reorganized EPA staff. In her inaugural speech, according to one interviewee, Gorsuch told employees, “We’re going to do more with less and we’re going to do it with fewer of you.” She realized part of this promise, reducing staff at the agency by 21% between 1981 and 1983. She also reorganized the agency in disruptive ways, dissolving the Office of Enforcement, for example, and distributing its staff to other offices. In the first year of the new administration, civil enforcement cases fell by about three quarters. The removal of “strong environmental players” through reorganization made everyone feel vulnerable, as did the hostility of political appointees to career staff. Congressional hearings eventually revealed that agency higher-ups had hit lists of career staff.8

The Reagan administration erected powerful new checks on agency rule making. An early executive order required regulatory review and cost–benefit analysis for new regulations, which was enforced by a new Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA). It disproportionately targeted EPA rules and acted with little transparency, allowing business influence to go unchallenged. Reagan also created the Presidential Task Force on Regulatory Relief, headed by Vice-President George Bush, to solicit industry complaints about environmental rules. Among those from which the task force sought relief was an EPA regulation to phase out leaded gasoline, which it only backed away from after tremendous public outcry.9

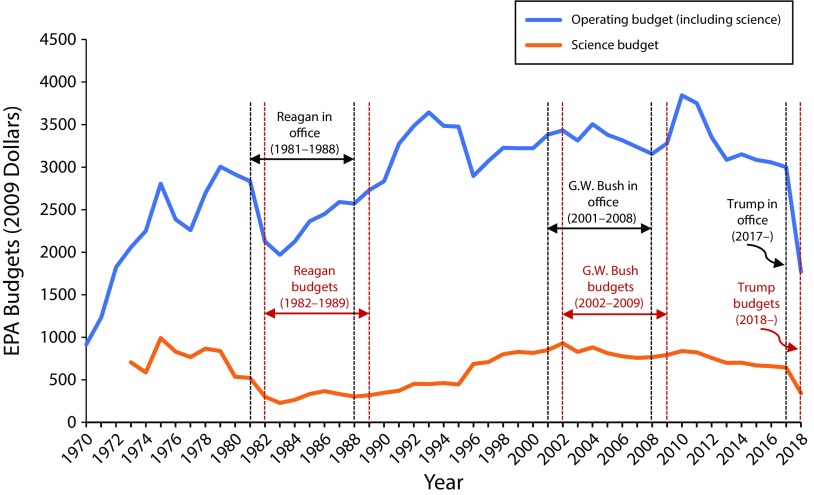

For all of Gorsuch’s and Reagan’s efforts to dial back this agency’s mandates, rules, and reach, they faced a serious obstacle in Congress, where Democrats still controlled the House. The Reagan administration was nevertheless able to slash the EPA budget, by coaxing support from conservative Southern House Democrats (some of whom soon switched parties), although not as much as Gorsuch had originally proposed.10 Between fiscal years 1980 and 1983, under Gorsuch, the EPA’s operating budget fell by 27%. The science budget tumbled 58% (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Budget for Operations and Science: 1970–2018

Source. “Budget of the United States Government,” Government Publishing Office from 1972 to 2018, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/54; Government Accounting Office, “Historical Tables,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals (accessed October 5, 2017).

Note. FY = fiscal year. The budget excludes grants to states and a few other EPA programs. Presidents propose a budget for the FY following the year they take office and for the FY after they leave office. As the graph shows, the EPA faced sharp cuts under the first Reagan administration (beginning in FY 1982) and faced even steeper proposed cuts in the Trump administration’s FY 2018 budget. Graph by EDGI.

The Reagan administration also launched interventions into science-based decision-making. It placed industry-aligned scientists on the EPA’s recently created Science Advisory Board. New administrators abruptly abandoned standard scientific and risk analysis methods. For example, despite evidence to the contrary emphasized by their own scientists, the assistant administrator for toxics at EPA, John Todhunter, resisted classifying formaldehyde as a human carcinogen. The Reagan administration also stonewalled the scientific consensus on acid rain, potentially delaying controls on air pollution that would eventually bring large public health cobenefits.11

The health tolls of this antiregulatory push at Gorsuch’s EPA were likely significant. Dysfunction and corruption in the Superfund hazardous waste program lead to delays that a House Energy Oversight Subcommittee investigation found had “increased significantly the risks of adverse health effects to thousands of people.” The agency’s seven-year refusal to recognize formaldehyde as a carcinogen meant that for many more years users of particle board and plywood had to breathe in this cancer-inducing chemical. From neglecting to warn about dioxin levels in Great Lakes fish to dragging its heels on a clean-up of heavily leaded soil around a Dallas, Texas, smelter, revelations of the literally toxic inaction of Gorsuch’s EPA eventually helped end her turn at the helm.12

RESISTANCE

The Reagan administration’s attacks soon encountered resistance and setbacks as scandals surged over conflicts of interest, obstruction of justice, and cuts to enforcement. Former EPA employees pointed to the key role of a Congress partly controlled by the Democrats in investigating, halting, and ultimately toppling the Gorsuch regime. But congressional investigations would not have been possible without the help of EPA staff, journalists, environmental groups, and concerned individuals.

Congressional investigations were often initiated and sustained by leaks engineered from inside the EPA in particular. An oppositional culture bloomed among career staff, who gathered in bars to plot strategies of resistance and unionized themselves to promote job security and scientific integrity. Assistant Administrator Bill Drayton, aided by a group of nearly 600 former EPA employees calling themselves “Save EPA,” funneled documents to members of Congress that initiated investigations into the Superfund program. When Gorsuch refused a congressional subpoena for further documents, 55 House Republicans joined the Democratic majority to charge her with contempt. Congressional and Justice Department investigations went on to expose major corruption and misconduct, much of it centered in the Superfund program, with director Rita Lavelle jailed for perjury. Gorsuch quit when the White House refused to defend her, joining some 21 other political appointees who were also driven out.13

In the less fragmented media environment of this time, media coverage and prioritizing of these revelations were vital, including the willingness of the New York Times to report on radical proposals for budget cuts and the mounting attention from other outlets. A sustained engagement of journalists, adeptly nourished by agency staff and environmental advocates, helped stir public concern about the threat to institutions and laws designed to protect the environment. Across the country, membership and contributions to environmental groups increased.14

Under pressure to restore EPA legitimacy, Reagan appointed the EPA’s first administrator, William Ruckelshaus, to replace Gorsuch. Ruckelshaus, a Republican environmentalist respected by both parties, promised that the EPA would operate “in a fishbowl”: transparently, avoiding conflicts of interest, and enabling public participation. He helped revitalize staff morale and bipartisan support for the EPA. But the agency’s budget was only partially restored. And Reagan’s initial expansion of White House authority over the agency was sustained, bolstering a longer-term corrosion of the EPA’s political independence.15

After Reagan, the presidency shifted back to Republican leadership more supportive of the mission of the EPA. George H. W. Bush appointed the “first professional environmentalist” to head the agency. William Reilly, previously president of the Conservation Foundation and the World Wildlife Fund, was sworn in at a special ceremony headlined by Bush himself that offered a pointed contrast to Gorsuch’s frosty inaugural. Over Bush’s four years, he strengthened the Clean Air Act and signed an international Framework Convention on climate change, acknowledging the human role in global warming. In the 1992 presidential campaign, he battled Clinton over who had the best environmental record.16

Clinton’s victory launched another round of ambitious environmental agenda setting, punctuated by the signing of the Kyoto Protocol and an executive order addressing environmental injustices, but progress slowed when the 1994 election swept conservative Republicans into power in Congress. Increasingly influential conservative media and think tanks, funded in part by fossil fuel industries, bolstered these Republicans’ campaigns. Many EPA employees remember 1994 as a watershed after which environmental policy and science became more politicized. Conservative congressional dominance initiated a “slow but steady starvation” of the EPA, with budget cuts and a refusal to reauthorize the tax that supported Superfund cleanups. The agency’s budget shrank even as it gained new laws and regulations to implement, with court-ordered deadlines. Legislative gridlock set in as environmental politics became increasingly polarized, further propelling the executive branch to the forefront of environmental policy.17

THE BUSH ASSAULT

The election of George W. Bush in 2000 brought a different strategic emphasis to presidential attacks on environmental health policy. In the campaign, Bush’s moderation reflected what were still considered the lessons of the Gorsuch era: he pledged to balance environmental protection with expanded development of coal, oil, and gas. In office, Bush’s challenge to the EPA remained less overtly confrontational but also more sophisticated than Reagan’s, relying on delaying decisions and undermining science rather than on cutting budgets. Although he did not set out to dismantle the EPA, his appointees launched offenses that shocked agency staff as well as outside scientists, state and local governments, environmental organizations, and much of the public.18

Bush’s appointment strategy was mixed: whereas many agency leaders were ideologically at odds with the environmental agencies they were charged to run, after the manner of Reagan, his choice to head the EPA was not. Chief among the former was Vice-President Dick Cheney, previously an oil executive, who served as a coordinator for much of the energy and environmental policy carried out under Bush. But the new EPA administrator Christine Todd Whitman had an agreeable environmental record as New Jersey governor and was well regarded by our interviewees.19

Like Reagan, the Bush administration turned to OIRA to gain tighter control over agency deliberations and rule making. Industries gained rights to challenge scientific research and economic analyses of federal agencies at the OIRA level, nudging Bush’s OIRA to turn remarkably selective. “It insisted on scientific rigor,” historian Richard Andrews wrote, “only when this served business’s agendas.”20 Such pressures slowed EPA proposals of new rules as well as the enforcement of established ones.

The Bush administration improved some health protections, such as diesel emission standards, but in many cases it sought to remove or delay protections. EPA employees remember the administration as generally less inclined to reject action than to “avoid having to actually take some action” through delays. A “timidity in policymaking” in water quality standards made it “almost impossible to make any progress,” and a growing host of what staff saw as spurious requirements prevented final decisions on storm water. The administration delayed a stricter drinking water standard for arsenic and temporarily excluded some facilities from Clean Air Act requirements. Reversing a 2000 EPA decision to regulate mercury emissions from power plants, Bush’s EPA proposed a less stringent replacement, “the Clean Air Mercury Rule.” When the courts vacated it as not sufficiently protecting public health, the agency failed to formulate any substitute. At the EPA, enforcement staff, investigations, and convictions fell. Staff reported difficulties with enforcement actions at facilities owned by Bush campaign donors.21

Even more systematically, the Bush administration sought to tilt the EPA’s scientific personnel and procedures toward politically favored policies. In reversing the earlier mercury rule for power plants, for example, the administration hid an EPA report on mercury’s health effects from public release and bypassed key EPA staff and a federal advisory panel in rule writing. In another instance, the administration increased the threshold for reporting toxic releases from 500 to 5000 pounds, drastically reducing how many events were reported.22

Bush’s most comprehensive assault on science involved climate change. Despite a campaign promise to regulate carbon dioxide, President Bush turned to denying the reality of anthropogenic climate change. Cheney, whose Energy Task Force recommended reducing regulations to promote coal, oil, and gas industries, frequently undermined Whitman, who quit in frustration. Web sites on climate change were not updated, reports were required to include language about the uncertainty of anthropogenic global warming, and EPA employees were prohibited from discussing or even mentioning climate change.23 These moves gave Bush, Cheney, and others the cover to withdraw from Kyoto Protocol talks, promote fossil fuel development—for example, by exempting fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act—and downplay renewable energy and energy conservation policies.24

The Bush administration’s reluctance and obfuscation had significant consequences for public health, which protests such as a 2004 letter signed by thousands of scientists had trouble allaying, but which were sometimes successfully challenged in court. Failing to tighten rules for mercury emissions from power plants until 2011 produced years of more harmful exposures to this and other hazardous air pollutants, despite solid science. The delays on mercury translated into thousands more neurobehavioral disorders from prenatal exposure and premature deaths from cardiovascular ailments among adults.25 On the climate front, the administration’s aggressive indifference delayed a regulatory reckoning with accumulating findings about climate change and public health. Only in 2009, after being pushed by a lawsuit and court decision, did the EPA publish its endangerment finding—that greenhouse gases were indeed a danger to public health—demanding regulation under the Clean Air Act. Had it done so earlier, regulations might already have been put in place to alleviate greenhouse gases’ current and future impacts, including worsening air pollution, intensifying storms and heat waves, and increases in water- and food-borne pathogens, on which the science had already accumulated.26

THE TRUMP ASSAULT

National environmental health policy is under assault again. President Trump, who campaigned to reduce the EPA to “little bits,” has pursued an attack on this agency that revives Reagan’s overt antiregulatory strategy and melds it with the science targeting of George W. Bush.

Like the early Reagan administration, Trump’s high-ranking appointments to the EPA, including Administrator Scott Pruitt, are hostile to the agency’s mission. Unlike Reagan era counterparts, however, they are more seasoned, with years of substantial backing from powerful think tanks and fossil fuel and chemical industries.27 The EPA’s leadership has pointedly marginalized career employees; for example, when Trump visited EPA headquarters, energy executives were present rather than career employees. Also like Reagan, the administration has sought deep budget and staff cuts at the EPA, more so than for any other agency. The 31% budget cut proposed for fiscal year 2018 is greater than what Reagan and Gorsuch achieved in two years. Pruitt has also pushed ahead with voluntary buyouts that reduced the EPA workforce to levels not seen since Reagan’s final year. These staff reductions are slated to continue. The consequences for EPA enforcement were already evident after nine months: there were one third fewer civil cases than under Obama and a quarter fewer than under George W. Bush.28

Like both Republican predecessors, the new administration has challenged agency regulations. It issued a flurry of executive orders exceeding both Reagan’s and Bush’s in their number and scope. These include the requirement that two rules be revoked for every new one proposed and the imposition of regulatory budgets that do not consider benefits. In addition, as of December 2017 the administration is reconsidering, delaying, or reversing 67 environmental rules, one third of these initiated by the new EPA leadership.29

Like the second Bush administration, the Trump administration has tried to control and manipulate the EPA’s use and dissemination of science. It has removed or obscured information about climate change from Web sites, dismissed scientific advisory panels, blocked scientists who receive EPA grants from advisement, and put a political appointee in charge of scientific grants. Pruitt now plans to sponsor a public “red team/blue team” debate to artificially litigate settled questions in climate science.30

As with formaldehyde under Reagan and mercury emissions under Bush, scientific studies demonstrate the public health benefits underlying the regulations that Pruitt’s EPA is contesting. Pruitt overturned a scheduled ban on chlorpyrifos, a widely used pesticide tied to low birthweight, attention problems, lowered IQ, and motor delays in children as well as health problems in pregnant women. On the basis of the EPA’s risk assessment, women of childbearing age will exceed the estimated safe level of dietary exposure to chlorpyrifos by 6200%, whereas children aged 1 to 2 years will exceed it by 14 000%. Pruitt and Trump have also declared an end to the nation’s primary climate change regulation, the Clean Power Plan (CPP). Designed to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, the CPP and policies favoring wind and solar power have spawned growing literature about health cobenefits, such as reducing small (< 2.5 µm) particulate and ozone pollution, that could forestall thousands of hospitalizations and premature deaths. Until the CPP or some comparable regulation goes into force, these preventable burdens of disease will continue.31

Trump’s and Pruitt’s deregulatory ambitions for the EPA are historically unrivaled, outstripping those of Reagan and Bush. Unlike during the Reagan administration, congressional investigations into improprieties are unlikely as long as conservative Republicans control Congress. Although congressional EPA budget proposals have not gone as far as Trump’s, they do include significant cuts. In addition, continuing legislative inaction on climate change is likely unless Democrats gain ground in the 2018 midterm elections. Thus, the courts will continue to be a critical arena for environmental politics. But Trump has influence over these too, with the opportunity to fill more judgeships than any previous president, and has begun packing these positions with extremely conservative judges.32

That the new administration enjoys so many more advantages reflects just how much the political and media landscapes have changed. Since the 1970s, party politics have become more polarized and environmental protection more partisan. As late as 1990, however, there was strong bipartisan public support for environmental protection. But many conservative Republican elites had already begun identifying environmentalism as an existential threat to American values. By 1994, when conservatives swept Congress, public attitudes on the environment had become far more partisan. Republican politicians have since increasingly voted against environmental protections, whereas Democrats have favored them.33 Nudging this shift, fossil fuel and chemical industries concerned about environmental regulations have increasingly funded antiregulatory think tanks and politicians, the latter especially so since the 2010 Citizens United Supreme Court decision.

Industries and think tanks have also sought to manufacture doubt about climate change and toxic threats, nourishing political and attitudinal divides.34 All these trends have been bolstered by how splintered the news media has become. After the 1980s, the rise of conservative talk radio, cable television networks such as Fox News, and the budding World Wide Web created a hospitable ecosystem for ideological polarization and attacks on mainstream media and science. Although two decades ago half of adherents of both parties trusted the news, today only 14% of Republicans do so, as compared with 62% of Democrats.35

These changes in public attitudes, party ideology, and media make it more difficult to resist attacks on environmental health now than in Reagan’s time. Even Reagan’s use of cost–benefit analysis for deregulation relied on economic science. But when Republicans have become so likely to mistrust science, when their rates of belief in anthropogenic climate change lie 35% points below Democrats’, when entire news outlets strive so devoutly to mirror the ideology of their audience, common touchstones that could stir a broader outrage are missing.36

Yet just as under Reagan, responses to this deregulatory drive are growing. Employees have fed damaging information to the press, rattling the administration, and have wielded newer tools such as social media to connect directly with the public about environmental issues.37 More Americans prioritize environmental protection over economic growth now than they did nearly two decades ago, and people are flocking to and funding environmental groups.38 Unlike in earlier decades, many multinational corporations now take climate change seriously. They are deeply critical of Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord and have pushed for policies that actively address climate change. In addition, many state governments have taken increasingly proactive roles in national environmental policy. Pruitt, for example, as Oklahoma attorney general, led a coalition of conservative states to block EPA regulations, including the CPP. But many states, particularly Northeastern and West Coast states, have pushed for stronger EPA regulations or have bypassed the national government in pursuing stronger state regulations and regional programs, such as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. Many of these states are now challenging the CPP rollback and are, along with cities, creating alliances to meet Paris Climate Accord goals.39

Finally, although bipartisan support for environmental health protection has withered, it is not dead. Nine years ago, the Republican standard-bearer, John McCain, favored carbon emissions reductions, and just last year, a bipartisan reform of toxics legislation actually passed.40 Reviving the legacies of Republican environmentalism and bipartisanship can fend off the current attacks and ultimately break through gridlock to produce policies that will protect the environmental health of all people.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this essay was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH; award T32ES023769).

This study was conceptualized, designed, analyzed, written, and supported by the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative.

The authors would like to thank the interviewees from the Environmental Protection Agency and Occupational Safety and Health Administration who contributed their wisdom and insights to this study.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The study was approved by the Northeastern University institutional review board (No. 16-11-34) and the Stonybrook University institutional review board (No. 996967).

ENDNOTES

- 1. In 2015, the EPA produced more major rules than any other regulatory department or agency. These regulations yielded $135.2–$522.6 billion in benefits, most of them health related, and $43.2–$50.9 billion in costs. No other department produced as many benefits. Office of Management and Budget, “2016 Draft Report to Congress on the Benefits and Costs of Federal Regulations and Agency Compliance With the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act,” 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/draft_2016_cost_benefit_report_12_14_2016_2.pdf (accessed February 25, 2018)

- 2. Offices included enforcement and compliance, water, the Superfund, brownfields, pesticides and other toxics, environmental justice, air and transportation, policy, communications, solid waste management, climate change, and administration. Positions included lawyers, scientists, engineers, policy analysts, and public relations officials. For the full EDGI report, see “The EPA Under Siege: Trump’s Assault in History and Testimony,” 2017, https://100days.envirodatagov.org/epa-under-siege.html (accessed February 25, 2018)

- 3. H. Sigman, “Hazardous Waste and Toxic Substances Policies” and P. Portney, “Air Pollution Policy,” both in Public Policies for Environmental Protection, ed. P. Portney and R. Stavins (Washington, DC: Resources for the Future, 2000), 230; R. Raucher, “Public Health and Regulatory Considerations of the Safe Drinking Water Act,” Annual Reviews in Public Health 17 (1996): 179–202; $2 trillion from: EPA, The Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act From 1990 to 2020: Final Report, Rev. A. (Washington, DC: Office of Air and Radiation, 2011); $50–$400 billion from: K. Matus, T. Yang, S. Paltsev, J. Reilly, and K.-M. Nam, “Toward Integrated Assessment of Environmental Change: Air Pollution Health Effects in the USA,” Climate Change 88, no. 1(2008): 59–92.

- 4. J. Brooks Flippen, Nixon and the Environment (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2000); R. Nixon, “Special Message to the Congress About Reorganization Plans to Establish the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,” in Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Richard M. Nixon, 1970 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1971), 578–579. State regulators: M. K. Landy, M. J. Roberts, and S. R. Thomas, The Environmental Protection Agency: Asking the Wrong Questions (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1990).

- 5. On Reagan’s campaign: J. Layzer, Open for Business: Conservatives’ Opposition to Environmental Regulation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 46–50, 88–92. On the Heritage Foundation: Philip Shabecoff, A Fierce Green Fire: The American Environmental Movement (Ann Arbor, MI: Island Press, 2012), 201.

- 6. On Reagan’s appointments in general: Shabecoff, Fierce Green Fire, 202–212. On Gorsuch: C. Hilliard, “Dedication Sends Two Colorado Legislators in Different Directions,” Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, June 25, 1980, 9BB; “Freshman Solons Get High Marks,” Greeley Tribune, June 3, 1977, 10; J. Lash, K. Gillman, and D. Sheridan, A Season of Spoils: The Reagan Administration’s Attack on the Environment (New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1984), 7–10.

- 7. R. N. L. Andrews, Managing the Environment, Managing Ourselves: A History of American Environmental Policy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 258–259; Lash, Gillman, and Sheridan, Season of Spoils, 41–43.

- 8. Gorsuch quotation and quotations about removal of and hostility to staff: EDGI, “EPA Under Siege,” 12–14. Staff reductions: Lash, Gillman, and Sheridan, Season of Spoils, 54–56. Enforcement: Joel Mintz, Enforcement at the EPA: High Stakes and Hard Choices (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2012), 43–48; Lash, Gillman, and Sheridan, Season of Spoils, 54–56. Hit lists: Lash, Gillman, and Sheridan, Season of Spoils, 36–40.

- 9. On new regulatory checks: David M. Shafie, Presidential Administration and the Environment: Executive Leadership in the Age of Gridlock (New York, NY: Routledge, 2013), 25. OIRA targeting the EPA: P. Behr, “Orders Pending to Cut Impact of Regulations,” Washington Post, February 4, 1981. OIRA transparency: Curtis Copeland, “Federal Rulemaking: The Role of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs” (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2009), 5–7. On the Task Force: Herbert Needleman, “The Removal of Lead From Gasoline: Historical and Personal Reflections,” Environmental Research 84, no. 1(2000): 30–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. N. J. Vig and M. E. Kraft, Environmental Policy in the 1980s: Reagan’s New Agenda (Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1984), 116.

- 11. On the Science Advisory Board: S. Hays, Explorations in Environmental History (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1998), 303. On formaldehyde: N. A. Ashford, C. W. Ryan, and C. C. Caldart, “Law and Science Policy in Federal Regulation of Formaldehyde,” Science 222, no. 4626 (1983): 894–900. Todhunter’s “penchant for conducting his own reanalysis” affected other determinations as well, including the risk analysis of ethyl dibromide. See M. R. Powell, Science at EPA: Information in the Regulatory Process (New York, NY: Routledge, 2014), 294–295. On acid rain: N. Oreskes and E. M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues From Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2010), 66–100. On acid rain cobenefits: B. Johnson, Environmental Policy and Public Health (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2006), 193.

- 12. On Superfund: US House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Investigation of the Environmental Protection Agency: Report on the President’s Claim of Executive Privilege Over EPA Documents, Abuses in the Superfund Program, and Other Matters (Washington, DC: Government Publishing Office, 1984), 10; E. Marshall, “EPA Indicts Formaldehyde, 7 Years Later,” Science 236, no. 4800 (1987): 381. On dioxin and smelter: Lash, Gillman, and Sheridan, Season of Spoils, 32–36, 132–139.

- 13. On leaks from inside the EPA: Lash, Gillman, and Sheridan, Season of Spoils, 67. On oppositional culture: “Organized Labor at EPA Headquarters: A History,” https://epaunionhistory.org (accessed October 5, 2017); M. Murphy, Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty: Environmental Politics, Technoscience, and Women Workers (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), chapter 5. On Drayton and “Save EPA”: J. Omang, “Ex-Official Leads Crusade to ‘Save EPA,’” Washington Post, January 19, 1982, A17; David Bornstein, How to Change the World: Social Entrepreneurs and the Power of New Ideas (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2004), esp. 56–58. On Superfund scandal investigations: R. Lazarus, “The Neglected Question of Congressional Oversight of EPA: ‘Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes’ (Who Shall Watch the Watchers Themselves)?” Law and Contemporary Problems 54, no. 4 (1991): 205–239; Andrew Szasz, “The Process and Significance of Political Scandals: A Comparison of Watergate and the ‘Sewergate’ Episode at the Environmental Protection Agency,” Social Problems 33, no. 3 (1986): 202–217.

- 14. P. Shabecoff, “Funds and Staff for Protecting the Environment May Be Halved,” New York Times, September 29, 1981, A1, 20. On the importance of media: Lash, Gillman, and Sheridan, Season of Spoils, 29. On environmental group membership: Andrews, Managing the Environment, 260.

- 15. On transparency: EPA, “Ruckelshaus Takes Steps to Improve Flow of Agency Information,” 1983, https://archive.epa.gov/epa/aboutepa/ruckelshaus-takes-steps-improve-flow-agency-information-fishbowl-policy.html (accessed February 25, 2018). On agency morale: Andrews, Managing the Environment, 259; EDGI, “EPA Under Siege,” 25.

- 16. “Bush Visits EPA Offices,” Washington Post, February 9, 1989, A17. Bush’s environmental policies: Andrews, Managing the Environment, 331–332; “Bush vs. Clinton: What Is an Environmental President?” 1992, http://articles.latimes.com/1992-09-27/opinion/op-488_1_environmental-policy (accessed February 25, 2018)

- 17. On Clinton’s environmental policies and new Congress: Andrews, Managing the Environment, 351–359. On fossil fuels, media, and think tanks: R. Dunlap and P. Jacques, “Climate Change Denial Books and Conservative Think Tanks,” American Behavioral Scientist 57, no. 6 (2013), 699–731. On 1994 as watershed and steady starvation: EDGI Interviews. On gridlock: C. Klyza and D. J. Sousa, American Environmental Policy: Beyond Gridlock (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 19–25.

- 18. On Bush’s campaign and rhetoric: Andrews, Managing the Environment, 360; On staff views of Bush: EDGI Interviews. The League of Conservation Voters rated George W. Bush “the most anti-environmental president in our nation’s history.” O. L. Graham, Presidents and the American Environment (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2015), 335.

- 19. Graham, Presidents, 330. On staff views of Whitman: EDGI Interviews.

- 20. Andrews, Managing the Environment, 382–383.

- 21. On arsenic, CAA, and mercury: Andrews, Managing the Environment, 358–377. On staff views and donors: EDGI Interviews. On enforcement generally: EDGI Interviews; J. Solomon and J. Eilperin, “Bush’s EPA Is Pursuing Fewer Polluters,” Washington Post, September 30, 2007.

- 22. On mercury: Union of Concerned Scientists, “Scientific Integrity in Policy Making,” 2004, http://www.ucsusa.org/our-work/center-science-and-democracy/promoting-scientific-integrity/reports-scientific-integrity.html (accessed February 25, 2018). On toxic releases: Shafie, Presidential Administration, 117.

- 23. On Bush’s campaign promise: Graham, Presidents, 331. On Cheney and Whitman: Andrews, Managing the Environment, 361–363, 380; EDGI Interviews. On Web sites, reports, and discussion of climate change: EDGI Interviews.

- 24. Andrews, Managing the Environment, 361–363; S. Wylie, “Securing the Natural Gas Boom: The Role of Science, the Academy and Regulatory Capture in the Exemption of Hydraulic Fracturing From Regulatory Oversight.” In Subterranean Estates: Life Worlds of Oil and Gas, ed. H. Appel, A. Mason, and M. Watts (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015).

- 25. On scientists’ objections: Union of Concerned Scientists, “Scientific Integrity”; E. Shogren, “Researchers Accuse Bush of Manipulating Science,” Los Angeles Times, July 9, 2004. On mercury: EPA, “Regulatory Impact Analysis for the Final Mercury and Air Toxics Standards” (EPA-452/R-11-011 [2011]), https://www3.epa.gov/airtoxics/utility/mats_final_ria_v2.pdf (accessed February 25, 2018). L. Trasande, C. Schechter, K. A. Haynes, and P. J. Landrigan, “Applying Cost Analyses to Drive Policy That Protects Children,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1076 (2006): 911–923. B. M. Kuehn, “Medical Groups Sue EPA Over Mercury Rule,” JAMA 294, no. 4 (2005): 415–416.

- 26. EPA, “Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings for Greenhouse Gases Under Section 202(a) of the Clean Air Act,” Federal Register 74, no. 239 (2009): 66496–66545 (“pathogens,” 66496).

- 27. C. Davenport, “Counseled by Industry, Not Staff, EPA Chief Is Off to a Blazing Start,” 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/01/us/politics/trump-epa-chief-pruitt-regulations-climate-change.html?_r=0 (accessed October 5, 2017). L. Dillon, C. Sellers, V. Underhill et al., “The Environmental Protection Agency in the Early Trump Administration: Prelude to Regulatory Capture,” American Journal of Public Health 108, suppl 2 (2018): S89–S94.

- 28. On staff levels: J. Heckman, “EPA May Offer More Buyouts, Early Retirement, Depending on Funding From Congress,” 2018, https://federalnewsradio.com/pay/2018/01/epa-may-offer-more-buyouts-early-retirement-depending-on-funding-from-congress (accessed February 25, 2018). On enforcement: E. Lipton and D. Ivory, “Under Trump, E.P.A. Has Slowed Actions Against Polluters, and Put Limits on Enforcement Officers,” 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/10/us/politics/pollution-epa-regulations.html (accessed February 25, 2018). E. Katz, “EPA Has Slashed Its Criminal Investigation Division in Half,” 2017, http://www.govexec.com/management/2017/08/epa-has-slashed-its-criminal-investigation-division-half/140509 (accessed February 25, 2018)

- 29.Popovich N., Albeck-Ripka L., Pierre-Louis K. “67 Environmental Rules on the Way Out Under Trump,” 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/10/05/climate/trump-environment-rules-reversed.html (accessed February 25, 2018)

- 30.Eilperin J. “EPA Now Requires Political Aide’s Sign-Off for Agency Awards, Grant Applications,” 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/epa-now-requires-political-aides-sign-off-for-agency-awards-grant-applications/2017/09/04/2fd707a0-88fd-11e7-a94f-3139abce39f5_story.html (accessed February 25, 2018). T. Cama, “EPA Head Suggests Climate Science Debate on TV,” 2017, http://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/341506-epa-head-suggests-climate-science-debate-on-tv (accessed February 25, 2018). B. Dennis and J. Eilperin, “Scott Pruitt Blocks Scientists With EPA Funding From Serving as Agency Advisers,” https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/scott-pruitt-blocks-scientists-with-epa-funding-from-serving-as-agency-advisers (accessed February 25, 2018)

- 31. On chlorpyrifos: EPA, “Tolerance Revocations: Chlorpyrifos,” 2015, https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0653-0001 (accessed February 25, 2018); EPA, “EPA Administrator Pruitt Denies Petition to Ban Widely Used Pesticide,” 2017, https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-administrator-pruitt-denies-petition-ban-widely-used-pesticide-0 (accessed February 25, 2018); EPA, “Chlorpyrifos: Revised Human Health Risk Assessment for Registration Review” (Washington, DC, 2016). On the CPP: J. J. Buonocore, K. F. Lambert, D. Burtraw, S. Sekar, and C. T. Driscoll, “An Analysis of Costs and Health Co-Benefits for a US Power Plant Carbon Standard,” PLoS ONE 11, no. 2016: e0156308; C. T. Driscoll, J. J. Buonocore, J. I. Levy et al., “US Power Plant Carbon Standards and Clean Air and Health Co-Benefits,” Nature Climate Change 5, no. 6(2015): 535–540; J. I. Levy, M. K. Woo, S. L. Penn et al., “Carbon Reductions and Health Co-Benefits From US Residential Energy Efficiency Measures,” Environmental Research Letters 11, no. 3 (2016): 034017; D. Millstein, R. Wiser, M. Bolinger, G. Barbose, “The Climate and Air-Quality Benefits of Wind and Solar Power in the United States,” Nature Energy 2, no. 9 (2017): 17134.

- 32. On congressional budgets: US Senate, “Explanatory Statement for the Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2018,” https://www.appropriations.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FY2018-INT-CHAIRMEN-MARK-EXPLANATORY-STM.PDF; H.R. 3354, 115 Congress (2017) (accessed February 25, 2018), https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr3354/BILLS-115hr3354pcs.pdf (accessed February 25, 2018). On judges: E. Shogren, “Trump’s Judges: A Second Front in the Environmental Rollback,” 2017, http://e360.yale.edu/features/trumps-judges-the-second-front-in-an-environmental-onslaught (accessed February 25, 2018)

- 33. On public attitudes and voting: A. M. McCright, C. Xiao, and R. E. Dunlap, “Political Polarization on Support for Government Spending on Environmental Protection in the USA, 1974–2012,” Social Science Research 48 (November 2014): 251–260. On elite attitudes: J. M. Turner, “‘The Specter of Environmentalism’: Wilderness, Environmental Politics, and the Evolution of the New Right,” Journal of American History 96, no. 1 (2009): 123–148; Layzer, Open for Business, 193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34. By 2005, there were almost twice as many conservative think tanks as liberal ones. A. Rich and K. Weaver, “Think Tanks in the Political System of the United States,” in Think Tanks in Policy Making—Do They Matter? ed. A. Rich, J. McGann, K. Weaver et al., Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Briefing Paper, September 2011, 19–21. D. Michaels and C. Monforton, “Manufacturing Uncertainty: Contested Science and the Protection of the Public’s Health and Environment,” American Journal of Public Health 51, suppl. 1 (2005): S39–S48; T. Skocpol and A. Hertel-Fernandez, “The Koch Network and Republican Party Extremism,” Perspectives on Politics 14, no. 3 (2016): 681–699.

- 35. J. T. Carmichael, R. J. Brulle, and J. K. Huxster, “The Great Divide: Understanding the Role of Media and Other Drivers of the Partisan Divide in Public Concern Over Climate Change in the USA, 2001–2014,” Climatic Change 141, no. 4(2017): 599–612; A. Dugan and Z. Auter, “Republicans’, Democrats’ Views of Media Accuracy Diverge,” Gallup News, August 25, 2017.

- 36. G. Gauchat, “Politicization of Science in the Public Sphere: A Study of Public Trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010,” American Sociological Review 77, no. 2 (2012): 167–187; R. E. Dunlap, A. M. McCright, and J. H. Yarosh, “The Political Divide on Climate Change: Partisan Polarization Widens in the US” Environment 58, no. 5 (2016): 4–23.

- 37.Cama T. “EPA Teaching Employees to Avoid Leaking Information,” 2017, http://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/351742-epa-holds-anti-leaking-training-for-employees (accessed October 5, 2017); “Hundreds of Current and Former EPA Employees Protest Trump’s Nominee in Chicago,” 2017, http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/breaking/ct-trump-epa-protest-chicago-20170206-story.html (accessed October 5, 2017); A. Brown, “Rogue Twitter Accounts Fight to Preserve the Voice of Government Science,” 2017, https://theintercept.com/2017/03/11/rogue-twitter-accounts-fight-to-preserve-the-voice-of-government-science (accessed October 5, 2017)

- 38.Kaplan L. “How Far Does the Post-Election Nonprofit Surge Extend?” 2017, https://nonprofitquarterly.org/2017/04/17/far-post-election-nonprofit-giving-surge-extend (accessed October 5, 2017); Gallup News, “Environment,” http://news.gallup.com/poll/1615/environment.aspx (accessed October 5, 2017)

- 39. On corporations and climate change: R. Luscombe, “Top US Firms Including Walmart and Ford Oppose Trump on Climate Change,” 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/dec/01/trump-climate-change-paris-withdrawal-ford-walmart (accessed February 25, 2018). On states and cities: E. Shogren, “As Trump Retreats, States Are Joining Forces on Climate Action,” 2017, http://e360.yale.edu/features/as-trump-retreats-states-are-stepping-up-on-climate-action (accessed February 25, 2018); N. Kusnetz, “US Mayors Back 100% Renewable Energy, Vow to Fill Climate Leadership Void,” 2017, https://insideclimatenews.org/news/26062017/mayors-conference-supports-100-percent-renewable-energy-electric-vehicles-climate-change (accessed February 25, 2018)

- 40. “John McCain’s Strategy for Confronting Global Climate Change,” 2008, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=93881 (accessed October 5, 2017); R. Denison, “Congress Passes Strong TSCA Reform, First Major Environmental Legislation in Over Two Decades,” 2016, http://blogs.edf.org/health/2016/06/07/congress-passes-strong-tsca-reform-first-major-environmental-legislation-in-over-two-decades (accessed October 5, 2017)