Abstract

Empirically based, consumer-informed programming to support students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) transitioning to college is needed. Informed by theory and research, the Stepped Transition in Education Program for Students with ASD (STEPS) was developed to address this need. The first level (Step 1) supports high school students and the second level (Step 2) is for post-secondary students with ASD. Herein, we review the extant research on transition supports for emerging adults with ASD and describe the development of STEPS, including its theoretical basis and how it was informed by consumer input. The impact of STEPS on promotion of successful transition into college and positive outcomes for students during higher education is currently being evaluated in a randomized controlled trial.

Keywords: Autism, College, Transition, Adult

Introduction

The number of adolescents and young adults diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who are either college-bound or enrolled in college is on a steep upward trajectory (White et al. 2011). Of the disabilities covered by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004), autism has been the fastest growing in terms of the percentage of children served (US DOE 2017). Recent estimates indicate that the majority of people with ASD do not have co-occurring intellectual disability (Christensen 2016). Unfortunately, young adults with ASD are less likely to enroll in college (2- or 4-year) than are people with other types of disabilities, such as speech/language impairments and specific learning disabilities (Wei et al. 2013). Research on the postsecondary outcomes of individuals with ASD appears to be concordant in the United States and in Europe (Karola et al. 2016; Newman et al. 2011). Programs that promote successful transition into postsecondary education may improve college enrollment and graduation outcomes for young adults with ASD.

Students with special needs, including those with ASD, in the United States cease to be supported under the auspices of IDEA upon exiting secondary education or reaching 21 years of age (IDEA, 2004). Special education services are provided by schools under IDEA to students who need accommodations in order to receive a free and appropriate education that meets their individual needs. The student need not self-advocate for these services, although often the student’s parents appeal for certain types of services. To continue to receive academic or related services from their postsecondary institution under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), students themselves (once of legal adult age) must disclose their disability, self-advocate, and provide necessary documentation regarding their disability. This transition to an advocacy-based approach has proven challenging for many people with ASD, who are less likely than students with other types of disabilities to take leadership of their own transition planning (Shogren and Plotner 2012). Per the ADA, however, many students who have disclosed a disability to educational support staff are entitled to accommodations which allow for access of educational material.

Among adolescents with ASD, both transition planning participation and identifying a transition goal of college enrollment while still in high school is associated with increased odds of attending a postsecondary institution (Wei et al. 2016). Integrating perceptions of adulthood and identity development at the high school level could also work to address postsecondary expectations and overall outcomes (Anderson et al. 2015). Programming to promote smooth transition from high school to postsecondary education may prove critical in the prevention of a host of adverse outcomes as well as promotion of success in college.

To receive accommodations once enrolled in college, students typically must register with their disability support office and disclose their disability. Students who disclose their disability before the end of their first year in college have been found more likely to graduate college than students who disclose later during their college tenure (Hudson 2013). Once registered for supports or accommodations, support staff must determine how to best meet the needs of the student. Though limited, research suggests that the profile of challenges and needs that students with ASD face is fairly unique, at least in relation to students with ADHD (Elias and White 2017). This finding suggests a need for ASD-specific transition programming.

Herein, we describe the development and content of a transition program designed specifically for students with ASD. The program itself is both theoretically informed and empirically based. The goal of the program is two-fold: to promote successful transition into postsecondary education and to improve the postsecondary school experience for students who have already matriculated.

Development of the STEPS Program

The Stepped Transition in Education Program for Students with ASD (STEPS) is theoretically based and consumer-informed. Conceptually, the mechanisms of action are improved self-regulation and self-determination. Self-determination (SD), or the ability to identify and achieve one’s own set goals (Field and Hoffman 1994), has been found to predict better post-school outcomes in typically developing individuals as well as among students with other disabilities (e.g., Chambers et al. 2007; Deci and Ryan 2002; Wehmeyer and Palmer 2003). Knowledge about one’s disability, as well as its associated strengths and difficulties, is critical to SD (Hitchings et al. 2001; Webster 2004). To target SD, STEPS focuses on building self-knowledge (e.g., about ASD, challenges in college), self-advocacy, and goal-directed behavior.

Self-regulation (SR) is a multifaceted construct that involves monitoring, oversight, and modulation of behavior, emotion, and cognition (Baumeister et al. 2007; Karoly 1993). SR is closely related to executive functioning capacity (e.g., one’s ability to update and monitor information, inhibit prepotent responses; Bridgett et al. 2013) and ability to regulate one’s emotions, or adapt and modify one’s emotional response in the service of identified goals (i.e., goal-directed behavior; Bridgett et al. 2013; Thompson 1994). Problems with SR, including executive function and emotion regulation impairments, are commonly ascribed to individuals with ASD (Corbett et al. 2009; Hewitt 2011; Mazefsky and White 2013). These deficits can be related to a host of problems such as inflexibility in routines, poor inhibitory control and time management, amotivation or impaired goal-directed behavior (e.g., Jahromi et al. 2009). In STEPS, SR is targeted in several ways including teaching effective stress management techniques, training in problem-solving and goal-setting, and outings (practices) related to the student’s identified goals.

A bottom-up, multi-method approach was taken to create a developmentally sensitive transition program that would support students with ASD both prior to and during the transition into college. To understand the challenges faced by postsecondary students with ASD and those contemplating high school graduation and matriculation into college, four separate studies were undertaken (Duke et al. 2013; Elias and White 2017; Elias et al. 2017; White et al. 2016a) to ensure that the final program addressed consumer-perceived needs. Such a participatory process approach is critical to the development of programs to promote consumer utility and, ultimately, dissemination and adoption (e.g., Chambers et al. 2007).

Following a preliminary focus group with college students with ASD and consultation with experts in the field of adult ASD and transition (Duke et al. 2013), the preliminary version of the transition support program was developed and piloted in a small group of college students (n = 6). Results from that pilot study were promising in terms of feasibility of implementation and acceptability to the students (White et al. 2016b). Subsequently, White and colleagues (2016a) used a mixed methods approach involving a nationwide online survey and in-person focus groups with three stakeholder groups (students with ASD, parents of students with ASD, and educators and school personnel), the results of which indicated fairly high convergence in identified challenges across the stakeholders. The most commonly identified needs were in the domains of interpersonal competence, ability to manage competing demands in college, and poor emotional regulation (White et al. 2016b). The third study included a series of focus groups with both secondary and postsecondary educators, results of which revealed themes of competence, autonomy and independence, and development of interpersonal relationships as the primary areas of difficulty faced by college students with ASD (Elias et al. 2017).

Subsequent to the pilot study (White et al. 2016a), the modified version of the STEPS program was shared with an expert consultant panel comprised of clinical scientists and educators in the fields of postsecondary academic accommodations for students with disabilities, ASD in adulthood and its assessment, and treatment development. These consultants provided feedback on the content areas covered and delivery modifications to optimize acceptability to the students, as well as the assessment procedures and study design. We also sought feedback on the program from parents and students with ASD, to gain additional insight that would inform refinement of the curriculum. These end-users offered practical suggestions, such as helping students in secondary school consider the possible benefits of a 2-year college prior to attending university away from home, addressing fears related to talking to people in authority in order to encourage self-advocacy, and openness to receiving technological support (e.g., apps) to improve skills. They also provided valuable insight into non-specific factors that can affect a student’s ability to feel empowered to self-advocate, such as ability to trust others’ intentions and limited experience in identifying supportive people (allies) in a new environment.

STEPS: Overview and Content

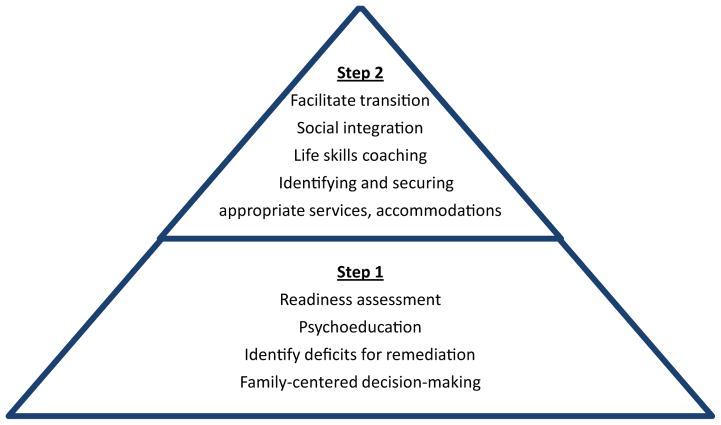

STEPS targets SD and SR, which are hypothesized to mediate positive outcomes such as college adjustment, academic performance, and healthy independent living. STEPS is comprised of two separate, distinct levels to match the student’s particular needs in relation to transition to higher education (see Fig. 1). Step 1 is for students currently in secondary school who are either planning for transition to college, or unsure of plans after secondary school. Step 2 is for currently enrolled college students, and those who have exited secondary school but have not yet matriculated into postsecondary education. The two steps are independent; in other words, the program was not designed such that students must complete Step 1 prior to Step 2, although that can happen. STEPS is individualized and person-centered. There are core content modules for each these curricula (see Table 1), but implementation is flexible so that the program can be individualized to the student’s interests, challenges, and goals. STEPS adopts a cognitive-behavioral approach to helping students develop SD and SR skills and make progress toward their transition goals. Completion takes 12–16 weeks, or the length of a typical academic semester.

Fig. 1.

Schemata of the content foci of Step 1 and Step 2

Table 1.

Content by modality across Step 1 and Step 2

| Counseling sessions | Corresponding online content | School personnel in-services (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||

| Planning and goal setting; determine readiness for college transition | Identifying services Promoting independence School-family communication Self-advocating Tools for success Transition involvement Transition planning |

ASD overview Addressing social difficulties Common challenges of students with ASD Easing transition Post-secondary options Preparing students Promoting student involvement in transition planning Understanding postsecondary resources |

| Learn about college expectations, supports, services | ||

| Identify areas to work on, challenges related to transition | ||

| Identify strategies to improve deficit areas | ||

| Practice self-advocacy and independent decision-making | ||

| Student rights and responsibilities | ||

| * Immersion experience | ||

| Step 2 | ||

| Planning and goal setting | College tools for success | N/A |

| Goals and challenges clarification | Identifying services | |

| Acceptance and change | Involvement in college | |

| Independent adulthood | Promoting independence | |

| Problem-solving I | School-family communication | |

| Problem-solving II | Self-advocacy | |

| Meeting new people | ||

| Increasing cognitive flexibility | ||

| Healthy stress management | ||

| Emotion regulation I | ||

| Emotion regulation II | ||

| Planning ahead | ||

Not within a sessions; immersion experience is separate activity

Step 1

The curriculum of STEP 1 involves active collaboration across stakeholders (i.e., students, parents, school personnel) throughout the program. The parent and student, upon entry into the program, identify a staff member at the student’s school who can assist the student (e.g., encourage participation in planning meetings at school) throughout STEPS. This is often a special education teacher, a general education teacher, or a case manager. All three stakeholders play critical and interdependent roles as part of the STEPS program. Developed for students who are at least 16 years of age, most Step 1 participants are in their last 2 years of secondary school.

There are six counseling sessions, which are held approximately every other week. Stakeholder participation in meetings is based on session content, with varying group composition (i.e., student only, student-parent, or student, parent, and school personnel) throughout the six sessions. The student is assigned activities (homework) to complete related to transition goals and, in between sessions, the counselor has regular checkins to monitor progress toward goals and completion of practice assignments. In addition to the six sessions in the clinic or at their current school, students take part in an immersion experience at either a 2- or 4-year postsecondary institution, depending on where they plan to matriculate post-graduation. During this immersion experience, which is coordinated and led by the counselor, students and their parents first tour campus, and then the student (usually without the parent but with the aid of the counselor, to promote independence) meets with the college’s disability support office, attends a college class, and eats lunch in a campus dining facility. Counselors also present specific didactics relating to life on a college campus, linking to STEPS content, at spaced intervals throughout the day. During the immersion experience, the counselor coaches the student on skills related to behavioral and emotion regulation (e.g., reviewing a class syllabus and discussing time management relative to the demands) and self-advocacy (e.g., asking questions during meetings with instructors and disability staff).

Prior to assisting a student, school personnel attend two half-day training sessions (in-services) on supporting students with ASD during transition. These sessions are primarily didactic in nature, but offer ample time for question and discussion. In addition to the content, case examples and small group activities are used to encourage dialogue and active learning.

Step 2

Students in Step 2 receive one-on-one counseling (12–13 sessions), community-based outings (practices), and online content over a 12 to 16-week period. The counselor acts as a ‘coach’ throughout the program, having regular contact via calls, texts, or emails outside of sessions with the student to try to ensure continued work toward the identified goals (e.g., ensuring student is studying for upcoming exam). The student’s parent/caregiver and school personnel, if one is identified, also have access to the online content (Table 1), but they do not attend counseling sessions. Similar to Step 1, there is flexibility within the manual to individualize the program for the student. Whilst building SD and SR, individualized goals are identified, for example, training in skills for independent living (e.g., finding part-time employment, managing finances, getting along with room-mates).

Whereas parent and school personnel are actively involved in Step 1, this is less so for Step 2, in order to be more developmentally sensitive to the young adults (college students) and promote their independence. Additionally, college students rarely have a single person in the college environment to serve as their identified school personnel; rather, they work with several support staff or counselors as well as multiple instructors. Typically, the parent and school personnel receive curriculum content solely via the online modules, unless the student participant opts to have greater involvement of them in the curriculum.

Step 2 targets SD and SR with a focus on social integration within the campus. The purpose of the community-based practice outings is typically to encourage social involvement that is goal-directed. As such, outings are completely individualized. For example, counselors might accompany the student to the first meeting of a social group, help the student get across campus between classes, try a new dining hall, or compose emails to professors.

Feasibility: Preliminary Data

STEPS is currently being evaluated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT), with participants assigned to either STEPS or ‘transition as usual’ (TAU), after which time they can enroll ‘open-label’ into STEPS. Although still enrolling, across both phases (Steps 1 and 2), reported satisfaction thus far is quite high. Upon program completion, students and parents completed satisfaction ratings, with all items scored on a 5-point scale (1 = not helpful, not likely; 5 = very helpful, very likely). Of a total of 26 students thus far (Step 1, n = 12; Step 2, n = 14), students reported that they found the program helpful (M = 4.31, SD = 0.79) and indicated they would likely recommend STEPS to others (M = 4.38, SD = 0.70). Similarly, parents reported that they found the program helpful (M = 4.39, SD = 1.03) and would likely recommend the program to others (M = 4.78, SD = 0.60). Qualitative feedback from program satisfaction questionnaires was similarly positive. One Step 1 student reported that the program “got [him] thinking about important tasks for ‘daily living’ when at college.” A Step 2 student reported, “[STEPS] helped me acknowledge and validate my feelings. It also helped me achieve some of my goals.”

Conclusion

Despite a growing population of college-bound and college-enrolled students with ASD, there is very little research on how to best support their academic and social success. It is critical that we address this gap, as it is clear that young adults with ASD who do not have co-occurring intellectual impairments face a host of adverse consequences related to under-employment (Engström et al. 2003), poor quality of life (van Heijst and Geurts 2015), and skill loss and inadequate services (Taylor and Seltzer 2011) as they transition out of secondary education. STEPS was developed as a developmentally sensitive, multi-component curriculum to promote successful transition into, and during, postsecondary education.

STEPS is novel in both in its focus on promoting college success for students with ASD as well as its development. There is evidence that participatory research is critical to overcoming health care disparities for people with ASD (e.g., Nicolaidis et al. 2011), yet there has been minimal research to inform transition support services. A participatory process approach was employed to develop STEPS in order to optimize the usability and effectiveness of the final program. It is also important that intervention and transition programs target identified mechanisms and have clearly documented procedures (i.e., manuals) for cross-site replicability and future dissemination. However, given the interpersonal variability that characterizes ASD (e.g., Hewitt 2011), it is equally critical that programs allow flexibility and individualization to meet student’s unique needs. The STEPS curriculum is the product of a consumer-driven, feedback-responsive development approach that seeks to balance the benefits of manualization with the necessity of personalization. This program is currently being evaluated in the context of a randomized controlled trial with secondary and postsecondary students with ASD.

Ultimately, if such programming is successful in achieving these objectives, it will empower students with ASD to achieve greater independence and higher quality of life, as well as contribute fully to society, economically and otherwise. Additionally, it is likely that programming that is informed by the preferences of the end-users and the needs of consumers will be more sustainable as well as impactful.

Acknowledgments

Funding This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R34MH104337).

Footnotes

Author Contributions SW conceived of the study, led development of STEPS, oversaw the evaluation study, and led writing of this manuscript. RE, NC, IS, and CC participated in evaluation of STEPS and implementation of the program, and provided input on program development. SA, EG, PH, and CM provided consultation on development of STEPS and the conduct of the RCT. All authors contributed to the present manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained prior to data collection.

References

- Anderson KA, McDonald TA, Edsall D, Smith LE, Taylor JL. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2015. Postsecondary expectations of high-school students with autism spectrum disorders; pp. 16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Schmeichel BJ, Vohs KD. Self-regulation and the executive function: The self as controlling agent. In: Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles. 2. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 516–539. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Oddi KB, Laake LM, Murdock KW, Bachmann MN. Integrating and differentiating aspects for self-regulation: Effortful control, executive functioning, and links to negative affectivity. Emotion. 2013;13(1):47–63. doi: 10.1037/a002953647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers CR, Wehmeyer ML, Saito Y, Lida KM, Lee Y, Singh V. Self-determination: What do we know? Where do we go? Exceptionality. 2007;15(1):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen DL. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years: Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2016;65:1–23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Constantine LJ, Hendren R, Rocke D, Ozonoff S. Examining executive functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and typical development. Psychiatry Research. 2009;166:210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Duke R, Conner CM, Kreiser NL, Hudson RL, White SW. Doing better: Identifying the needs and challenges of college students with autism spectrum disorders. Poster presented at the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Nashville, TN. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elias R, Muskett A, White SW. Short report: Understanding the postsecondary transition needs of students with ASD: Qualitative insights from campus educators. 2017. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Elias R, White SW. Autism goes to college: Understanding the needs of a student population on the rise. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;0(0):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3075-7. Available from http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10803-017-3075-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engström I, Ekström L, Emilsson B. Psychosocial functioning in a group of Swedish adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice. 2003;7(1):99–110. doi: 10.1177/1362361303007001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field S, Hoffman A. Development of a model for self-determination. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals. 1994;17:159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt LE. Perspectives on support needs of individuals with autism spectrum disorders: Transition to college. Topics in Language Disorders. 2011;31(3):273–285. doi: 10.1097/TLD.0b013e318227fd19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchings WE, Lusso DA, Ristow R, Horvath M, Retish P, Tanners A. The career development needs of college students with learning disabilities: In their own words. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 2001;16:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RL. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Virginia Tech; Virginia: 2013. The effect of disability disclosure on the graduation rates of college students with disabilities. [Google Scholar]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, P.L. 108–446, 20 U.S.C. $ 1400 et seq.

- Jahromi LB, Kasari CL, McCracken JT, Lee LSY, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, … Posey DJ. Positive effects of methylphenidate on social communication and self-regulation in children with pervasive developmental disorders and hyper-activity. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:395–404. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0636-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karola D, Julie-Ann J, Lyn M. School’s out forever: Postsecondary educational trajectories of students with autism. Australian Psychologist. 2016;51(4):304–315. doi: 10.1111/ap.12228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karoly P. Mechanisms of self-regulation: A systems view. Annual Review of Psychology. 1993;44:23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, White SW. Emotion regulation: Concepts and practice in autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman L, Wagner M, Knokey A-M, Marder C, Nagle K, Shaver D, Schwarting M. A report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) (NCSER 2011-3005) Menro Park, CA: SRI International; 2011. The post-high school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 8 years after high school. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, McDonald K, Dern S, Ashkenazy E, Boisclair S, … Baggs A. Collaboration strategies in nontraditional community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons from an academic-community partnership with autistic self-advocates. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2011;5(2):143–150. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shogren K, Plotner AJ. Transition planning for students with intellectual disability, autism, or other disabilities: Data from the national longitudinal transition study-2. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;50:16–30. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Seltzer MM. Employment and post-secondary educational activities for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41(5):566–574. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1070-3. doi:10.1007/ s10803-010-1070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition: Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1994. pp. 25–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Office of Special Education Programs, Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, selected years, 1979 through 2006; and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) database. 2017 Retrieved April 20, 2017, from http://tad-net.public.tadnet.org/pages/712.

- van Heijst BFC, Geurts HM. Quality of life in autism across the lifespan: A meta-analysis. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice. 2015;19(2):158–167. doi: 10.1177/136236131517053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster DD. Giving voice to students with disabilities who have successfully transitioned to college. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals. 2004;27:151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Wehmeyer ML, Palmer SB. Adult outcomes for students with cognitive disabilities three years after high school: The impact of self-determination. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities. 2003;38:131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Yu JW, Shattuck P, McCracken M, Blackorby J. Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) participation among college students with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43:1539–1546. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1700-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Wagner M, Hudson L, Yu JW, Javitz H. The effect of transition planning participation and goal-setting on college enrollment among youth with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0741932515581495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Elias RE, Salinas CE, Capriola N, Conner CM, Asselin SB, Miyazaki Y, Mazefsky CA, Howlin P, Getzel EE. Students with autism spectrum disorder in college: Results from a preliminary mixed methods needs analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016a;56:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Ollendick TH, Bray BC. College students on the autism spectrum: Prevalence and associated problems. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice. 2011;3(6):683–701. doi: 10.1177/1362361310393363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Richey JA, Gracanin D, Coffman M, Elias R, LaConte S, Ollendick TH. Psychosocial and computer-assisted intervention for college students with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2016b;51(3):307–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]