Abstract

Background

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) has become one of the most common neuroendoscopic procedures.

Methods

In this article, we will review the major milestones in the history of ETV development from its early use by Walter Dandy to the techniques currently employed with advanced technology.

Conclusions

ETV has become an important technique in the armamentarium of the neurosurgeon. From a meager beginning with few applications, our knowledge of long-term outcomes has evolved. ETV has a rich history and more recently, has had a renewed interest in its use. Our current understanding of its indications is growing and is based on a century of development through trial and error.

Keywords: Ventriculostomy, Hydrocephalus, Neuroendoscopy, History, Neurosurgery

Introduction

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy, or “ETV,” is a technique used mainly to treat obstructive hydrocephalus by making an opening in the floor of the third ventricle using an endoscope to permit CSF drainage into the basal cisterns [9]. In 1947, McNickle gave it a one-line description stating, “Ventriculostomy is simply an attempt to bypass obstruction” [14]. The concept of ETV dates back to the early decades of the 20th century and has continued to evolve since then. With a renewed interest in this surgical technique, a review of its history is warranted.

Historical review

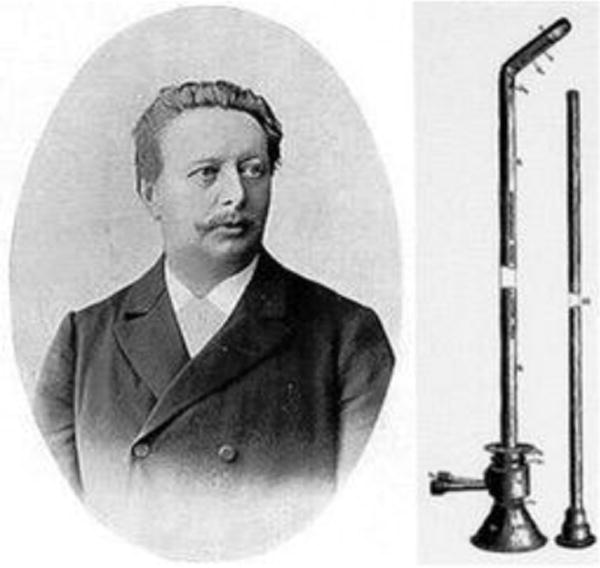

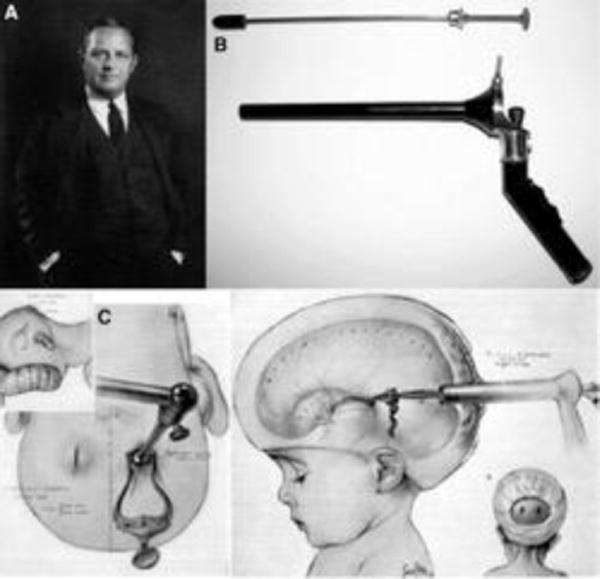

The modern endoscope was first introduced by German urologist Maximilian Carl-Friedrich Nitze (1848 – 1906) (Fig. 1); in 1879 he presented the Nitze-Leiter cystoscope, which opened the door for neurosurgeons to adapt endoscopy to their procedures [26]. Neuroendoscopy began in 1910 when the urologist Victor Lespinasse (1878 –1946), using a cystoscope, made the first attempt to treat hydrocephalus by destroying the choroid plexus of two young patients [5]. Later, in 1922, Walter Dandy (1886-1946) also used a cystoscope to visualize the ventricles (Fig. 2). He noted that he was able to inspect the lateral ventricle, the foramen of Monro, the choroid plexus and even the blood vessels in the wall of the ventricle; thus the term “ventriculoscopy” was used for the first time. Dandy also described an attempt to relieve hydrocephalus using a small cystoscope. A subfrontal approach to the anterior wall (lamina terminalis) of the third ventricle was used. However, this technique was morbid as one of the optic nerves was sacrificed for the approach. Dandy conducted this procedure six times but never gave an account of the outcomes. However, he stated that pneumoventriculography provided the same level of visualization and that endoscopy was not ready to replace traditional surgical methods in the treatment of hydrocephalus [3, 4, 20].

Fig. 1.

Maximilian Carl-Fredrich Nitze portrait and the Nitze endoscope. Reprinted from World Neurosurgery 77(1) Zada G, Liu C, Apuzzo ML, “Through the looking glass”: optical physics, issues, and the evolution of neuroendoscopy, 92-102. Copyright (2012), with permission from Elsevier.

Fig. 2.

Walter Dandy portrait (A), Dandy’s ventriculoscope (B) Dandy’s illustrations of the ventriculoscopy procedure (C). Reprinted from World Neurosurgery 77(1) Zada G, Liu C, Apuzzo ML, “Through the looking glass”: optical physics, issues, and the evolution of neuroendoscopy, 92-102. Copyright (2012), with permission from Elsevier.

Around the same time of Dandy’s trials, William Jason Mixter (1880-1958) (Fig. 3) performed the first-ever third ventriculostomy in the treatment of a non-communicating hydrocephalus using an uretheroscope in 1923. His attempt was successful; the patient’s head circumference decreased and the pressure in the ventricles and the lumbar cistern equilibrated [8, 12, 20]. Also in 1923, Temple Fay (1895-1963) and Francis Grant (1891-1967) developed a method to capture clear black and white images of the ventricles using a cystoscope. Their case report of a 10-month-old Italian boy illustrated an attempt to fenestrate the corpus callosum in order to treat hydrocephalus, but they were not able to divide the corpus callosum due to a malfunction in the cystoscope that they were using. Although the procedure did not go as planned, they concluded that it was safe to visualize the ventricle using an endoscope without causing ventricular hemorrhage or other complications [6, 8]

Fig. 3.

William J Mixter portrait. Reprinted from World Neurosurgery 77(1) Zada G, Liu C, Apuzzo ML, “Through the looking glass”: optical physics, issues, and the evolution of neuroendoscopy, 92-102. Copyright (2012), with permission from Elsevier.

More than 10 years later, in 1934, Tracy Putnam (1894-1975) (Fig. 4) introduced the “ventriculoscope” aiming to perform the choroid plexectomy that Dandy had performed with the cystocope. Putnam gave very specific details of his device and how it worked; he explained that it consisted of an optical glass rod with three grooves, one longitudinal groove for the light source and two other grooves for the diathermy electrodes. He went on to describe that his ventriculoscope came in two sizes, one was 10 cm long and six mm in diameter while the other was 18 cm long and 7 mm in diameter. Putnam’s results were published in 1943, and he reported operating on 42 patients with 11 intraoperative deaths [8, 15, 16, 20].

Fig. 4.

Tracy J. Putnam portrait. Reprinted from World Neurosurgery 79(2), Decq P, Schroeder HW, Fritsch M, Cappabianca P, A history of ventricular endoscopy, S14.e1-S14.e6, Copyright (2013), with permission from Elsevier.

In 1935, John Scarff (1898-1979) adapted an enhanced version of Putnam’s ventriculoscope. While both of them shared the same concept, the devices were slightly different. Scarff’s ventriculoscope had an irrigation system to maintain intraventricular pressure, thereby preventing ventricular collapse. His device was also equipped with a flexible unipolar probe and a better viewing wide-angle lens. Scarff also suggested that the opening into the third ventricle should be a little more than just a puncture [5, 8, 19].

In 1947, H. F. McNickle made a significant contribution to the principle of ventriculostomy itself rather than the technique; he was not convinced that the procedure should be limited to non-communicating hydrocephalus. He reported two cases of communicating hydrocephalus that responded to ventriculostomy and described the classification of patients into communicating and non-communicating as “arbitrary” and “overemphasized.” He also argued that choroid plexectomy was not the correct answer to hydrocephalus because decreasing the production of cerebrospinal fluid would not clear the obstruction itself [14].

In 1949, Frank Nulsen (1916-1994) and Eugene Spitz (1919-2006) introduced the concept of the shunt as a new method for the treatment of hydrocephalus by draining CSF to the right atrium or to the peritoneum. In 1955, John Holter (1916 – 2003) added a one-way valve to the device; Holter’s invention was inspired by the death of his son, Casey, from the complications of myelomeningocele and hydrocephalus. The procedure developed by Holter was considered relatively easy, hence ventriculostomy lost its luster and neurosurgeons became less enthusiastic about it [1, 2, 20]. However, a new wave of development came from Europe in the 1960s. In 1961, Dereymacker et al. adapted a new method for ventriculostomy and made a perforation into the lamina terminalis using the light source itself. Their sample consisted of 15 patients, but only 2 of them had a decrease in their ventricular size. [5]

In the 1960s, French neurosurgeon Gerard Guiot (1912-1998) (Fig. 5) revived the whole idea of neuroendoscopy after its long sleep. His first endoscopic third ventriculostomy was successfully performed on August 8, 1962 on a 40-year-old man with a history of head trauma. The endoscope allowed Guiot to clearly see a tumor that was attached to the foramen of Monro as well as a clear view of the lateral ventricle. Using a soft spatula, he was able to push the tumor into the third ventricle and perforate its floor. His second trial was conducted a year later on an infant with hydrocephalus and the same technique was used and the patient’s hydrocephalus resolved after the ventriculostomy. He continued to use this technique on several other occasions [5].

Fig. 5.

Gerard Guiot portrait. Reprinted from World Neurosurgery 79(2), Decq P, Schroeder HW, Fritsch M, Cappabianca P, A history of ventricular endoscopy, S14.e1-S14.e6, Copyright (2013), with permission from Elsevier.

The next generation of neuroendoscopy would arrive in the 1970s based on a major contribution by British physicist Harold Hopkins (1918 – 1994) whose innovative work paved the path toward rigid and flexible endoscopes used today [8]. Takanori Fukushima (born 1942) (Fig. 6) invented the “ventriculofiberscope” (Fig. 7) and in 1973, became the first neurosurgeon to use a flexible endoscope for ventriculostomies. [5, 7, 8] Around the same time, in England, Hugh Griffith (1930 – 1993) recommended the endoscopic procedure as “a first line treatment for childhood hydrocephalus.” He used Hopkins’ rigid endoscope to perform third ventriculostomy as well as choroid plexus coagulation to treat hydrocephalus [8, 10]. In 1976, Harold Hoffman (1932 – 2004) performed a series of endoscopic third ventriculostomies using stereotactic guidance and in 1980, he noted that the percutaneous stereotactic-guided approach yielded better results than open craniotomy [11, 20, 21]. In 1977, Michael Apuzzo (born 1940) became the first to use a side-viewing wide-angled lens in neuroendoscopy [5].

Fig. 6.

Intraoperative photograph of Takanori Fukushima

Fig. 7.

Photograph of ventriculofiberscope introduced by Takanori Fukushima

Another development came in 1996 when Andreas Rieger introduced the idea of using ultrasound to pass the endoscope into the third ventricle through the foramen of Monro. He described this technique as “exact as stereotaxy but faster and easier” [17]. In 1998, Veit Rohde suggested that the use of infrared-based frameless streotaxy in neuroendoscopic ventriculostomy resulted in decreased post-operative morbidity [18]. Entering the new millennium there was another addition of technology to the procedure. In 2002, endoscopy was used along with stereotactic navigation in order to decrease vascular injury during the procedure and in 2004, the first instance of a robot being used in third ventriculostomy was reported [20]. Nowadays, cutting-edge technology has given the neurosurgeon a high-definition picture of the ventricles and with the implementation of the Endoscopic Third Ventriculostomy Success Score “ETVSS”, we are able to predict the outcome of the procedure with greater confidence [13, 20].

One of the most recent contributions to the development of ETV came from Benjamin Warf (Fig. 7) of the Boston Children’s Hospital. He reported the combination of both ETV and choroid plexus cauterization (CPC) in order to yield better results in the treatment of hydrocephalus especially in developing countries where shunt procedures may be hazardous due to the lack of resources to revise a shunt after a malfunction or an infection. Based on that assumption, Warf conducted his EVT-CPC trials in East Africa from June 2001 till December 2004. His initial results in 2005 suggested that ETV-CPC was better than ETV alone in patients younger than one year of age, especially those with myelomeningocele and “nonpostinfectious” hydrocephalus. In 2012, after conducting several trials, it was clear that infants below one year of age with congenital aqueductal stenosis would benefit the most from ETV-CPC. In 2014, Warf validated his results from Uganda by conducting ETV-CPC trials on patients in North American and the results were consistent with his previous experience. He also found that ETV-CPC carries a lower risk of postoperative infection or malfunction compared to shunt procedures, offering a substantial cost-effectiveness advantage [23–25]. Moreover, a recent study by the Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network (HCRN) concluded that ETV-CPC is a safe procedure and provides an effective alternative to the shunt. The results also suggested that full choroid plexus coagulation correlated with a higher success rate [13].

Conclusion

The wide use of endoscopic third ventriculostomy is a product of a century of innovation and development performed by a long list of visionaries. Continued improvements both in technology and in our understanding of long-term patient outcomes will further refine and improve this neurosurgical treatment.

Fig. 8.

Photograph of Benjamin Warf

References

- 1.Boockvar JA, Loudon W, Sutton LN. Development of the Spitz-Holter valve in Philadelphia. J Neurosurg. 2001;95(1):145–147. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.1.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chrastina J, Novak Z, Riha I. Neuroendoscopy. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2008;109(5):198–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dandy WE. An operative procedure for hydrocephalus. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1922;33:189–190. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dandy WE. Cerebral ventriculoscopy. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1922;33:189. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decq P, Schroeder HW, Fritsch M, Cappabianca P. A history of ventricular neuroendoscopy. World Neurosurg. 2013;79(2):S14–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fay T, Grant FC. Ventriculoscopy and intraventricular photography in internal hydrocephalus: report of case. J Am Med Assoc. 1923;80(7):461–463. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukushima T, Ishijima B, Hirakawa K, Nakamura N, Sano K. Ventriculofiberscope: a new technique for endoscopic diagnosis and operation: technical note. J Neurosurg. 1973;38(2):251–256. doi: 10.3171/jns.1973.38.2.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geiger M, Cohen AT. The history of neuroendoscopy. In: Cohen A, Haines SJ, editors. Concepts in Neurosurgery Vol 7: Minimally Invasive Techniques In Neurosurgery. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1995. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. 5th. Thieme; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith HB, Jamjoom AB. The treatment of childhood hydrocephalus by choroid plexus coagulation and artificial cerebrospinal fluid perfusion. Brit J Neurosurg. 1990;4(2):95–100. doi: 10.3109/02688699008992706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman HJ, Harwood-Nash D, Gilday DL. Percutaneous third ventriculostomy in the management of noncommunicating hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 1980;7(4):313. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu W, Li KW, Bookland M, Jallo GI. Keyhole to the brain: Walter Dandy and neuroendoscopy: Historical vignette. J Neurosurg: Pediatrics. 2009;3(5):439–442. doi: 10.3171/2009.1.PEDS08342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulkarni AV, et al. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy and choroid plexus cauterization in infants with hydrocephalus: a retrospective Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network study: Clinical article. J Neurosurg: Pediatrics. 2014;14(3):224–229. doi: 10.3171/2014.6.PEDS13492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulkarni AV, Riva-Cambrin J, Browd SR. Use of the ETV Success Score to explain the variation in reported endoscopic third ventriculostomy success rates among published case series of childhood hydrocephalus: Clinical article. J Neurosurg: Pediatrics. 2011;7(2):143–146. doi: 10.3171/2010.11.PEDS10296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNickle HF. The surgical treatment of hydrocephalus: A simple method of performing third ventriculostomy. Brit J Surg. 1947;34(135):302–307. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18003413515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Putnam TJ. Treatment of hydrocephalus by endoscopic coagulation of the choroid plexus: description of a new instrument and preliminary report of results. New Engl J Med. 1934;210(26):1373–1376. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Putnam TJ. Surgical treatment of infantile hydrocephalus. California Med. 1953;78(1):29–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieger A, Rainov NG, Sanchin L, Schöpp G, Burkert W. Ultrasound-guided endoscopic fenestration of the third ventricular floor for non-communicating hydrocephalus. Min Inv Neurosurg. 1996;39(1):17–20. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1052209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rohde V, Reinges MHT, Krombach GA, Gilsbach JM. The combined use of image-guided frameless stereotaxy and neuroendoscopy for the surgical management of occlusive hydrocephalus and intracranial cysts. Brit J Neurosurg. 1998;12(6):531–538. doi: 10.1080/02688699844385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scarff JE. Third ventriculostomy as the rational treatment of obstructive hydrocephalus. J Pediatr. 1935;6:870–871. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitt PJ, Jane JA., Jr A lesson in history: the evolution of endoscopic third ventriculostomy. Neurosurg Focus. 2012;33(2):E11. doi: 10.3171/2012.6.FOCUS12136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sgouros S. Neuroendoscopy: Current Status and Future Trends. Springer; Berlin: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone SS, Warf BC. Combined endoscopic third ventriculostomy and choroid plexus cauterization as primary treatment for infant hydrocephalus: a prospective North American series: Clinical article. J Neurosurg: Pediatrics. 2014;14(5):439–446. doi: 10.3171/2014.7.PEDS14152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warf BC. Comparison of endoscopic third ventriculostomy alone and combined with choroid plexus cauterization in infants younger than 1 year of age: a prospective study in 550 African children. J Neurosurg. 2005;103(6 Suppl):475–481. doi: 10.3171/ped.2005.103.6.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warf BC, Tracy S, Mugamba J. Long-term outcome for endoscopic third ventriculostomy alone or in combination with choroid plexus cauterization for congenital aqueductal stenosis in African infants: Clinical article. J Neurosurg: Pediatrics. 2012;10(2):108–111. doi: 10.3171/2012.4.PEDS1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zada G, Liu C, Apuzzo ML. “Through the looking glass”: optical physics, issues, and the evolution of neuroendoscopy. World Neurosurg. 2012;77(1):92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]