Abstract

Food security and good nutrition are key determinants of child well-being. There is strong evidence that cash transfers such as South Africa’s Child Support Grant (CSG) have the potential to help address some of the underlying drivers of food insecurity and malnutrition by providing income to caregivers in poor households, but it is unclear how precisely they work to affect child well-being and nutrition. We present results from a qualitative study conducted to explore the role of the CSG in food security and child well-being in poor households in an urban and a rural setting in South Africa.

Setting

Mt Frere, Eastern Cape (rural area); Langa, Western Cape (urban township).

Participants

CSG recipient caregivers and community members in the two sites. We conducted a total of 40 in-depth interviews with mothers or primary caregivers in receipt of the CSG for children under the age of 5 years. In addition, five focus group discussions with approximately eight members per group were conducted. Data were analysed using manifest and latent thematic content analysis methods.

Results

The CSG is too small on its own to improve child nutrition and well-being. Providing for children’s diets and nutrition competes with other priorities that are equally important for child well-being and nutrition.

Conclusions

In addition to raising the value of the CSG so that it is linked to the cost of a nutritious basket of food, more emphasis should be placed on parallel structural solutions that are vital for good child nutrition outcomes and well-being, such as access to free quality early child development services that provide adequate nutritious meals, access to adequate basic services and the promotion of appropriate feeding, hygiene and care practices.

Keywords: child support grant, cash transfers; child wellbeing, food security, child nutrition

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of this study is that it contributes to the current relatively small evidence base of qualitative studies that seek to understand how cash transfers in low and middle income settings play a role in child nutrition and wellbeing.

A methodological strength of this manuscript is that it utilises a qualitative research approach that combines in-depth individual interviews which give an individual-level experience of the Child Support Grant, as well as focus group discussions that give a community-level view of the topic under investigatio

A limitation of the study is that since this is a qualitative inquiry, findings cannot be generalised outside the study sites where the research was conducted. However, inferences can be drawn to broaden our understanding of how cash transfers affect child nutrition and wellbeing in low and middle income settings.

Background

Food security and good nutrition are key determinants of child well-being.1 2 There is global consensus in the literature that health and nutritional status in early life have impacts that go beyond childhood, affecting human development and later life productivity. Poor child health outcomes such as undernutrition in the early years of life, especially the first 1000 days, have irreversible negative ripple effects on illness and disability, timing of entry into school, educational attainment, economic productivity and, ultimately, the transmission of poverty from generation to generation.2 3 Stunting—defined as height-for-age of <–2 z-scores below the median—is a measure of chronic inadequate dietary intake and reflects long-term undernutrition. While the evidence on levels of stunting in South Africa appears mixed, with some reporting a modest decline on the one extreme,4 5 and others reporting increasing rates on the other,1 one fact remains clear: South Africa continues to experience stunting rates for children under the age of 5 years that are inconsistent with its standing as an upper middle-income country.6–8 Different data sources on stunting report different rates for the period 1993–2012, as a result of using different sampling frames, sample sizes and age ranges of children measured, but whichever sources are used, the clear message is that stunting rates have at best moderately improved or at worst stagnated during this period –never going above 30% and never reducing below 20%.7 In 1993, stunting rates for under-5s in South Africa were as high as 30%, in 2008 about 25% of children were reported to be stunted6 9 and in 2012, they were between 21.5% and 26.4%.1 7 The latest South African Demographic Health Survey reports stunting at 27% for children under the age of 5 years in 2016.10

There is a growing view among policy-makers that cash transfers (CTs) have the potential to help address some of the underlying drivers of food insecurity and malnutrition by providing income to caregivers in poor households.3 4 As a result, CTs have become a policy instrument of choice for addressing a range of child health and development outcomes. Over 130 countries in the Global South have unconditional cash transfer (UCTs) programmes and about 63 have conditional CT programmes.11 However, specific evidence on child CTs and nutrition is mixed. In 2012, a rapid review of evidence on conditional and UCTs in low-income and middle-income countries found that overall they had no impact on child-height for age.12 More recently, a rigorous review of evidence on child CTs implemented in low-income and middle-income settings found that only 5 out 13 impact assessments reported statistically significant improvements in stunting.11 Bastagali et al 11 suggest that the challenge to determining the impact of CTs on child growth measures is the fact that child growth is not influenced through income support alone.

In South Africa, the Child Support Grant (CSG) was introduced in 1998 with the main aim of providing nutrition support for children living in poor households.13 As the largest CT programme in South Africa and the continent, reaching more than two-thirds of all children in the country,8 the CSG is widely regarded as the most effective child poverty alleviation strategy in the country.9 The CT pays out R340i (US$25.40) per month to any child whose parent/s earn less than 10 times the amount of the grant per month. The CSG is non-contributory and can be received by children from birth to 18 years. It has only one ‘soft-condition’ii for continued receipt: school attendance. Additionally, it has requirements attached to the application process such as the possession of an Identity Document by the mother (or primary caregiver) and of a birth certificate by the child.

Early research on the CSG indicated that the grant was associated with improved height-for-age growth for children under the age of 3 years14 and reduced hunger.15 Recent research on the CSG suggests, however, that while it mitigates extreme poverty and hunger,9 15 16 it does not protect against food insecurity and malnutrition.7 17 18 While this fact is increasingly accepted, there is little agreement about reasons for it. Media and some commentators have argued that the grant’s lack of impact results from the fact that primary caregivers misuse it by spending it on alcohol or personal non-essentials, unrelated to the intended goals of the CT programme, although these allegations have yet to be substantiated with rigorous evidence.19 In contrast, others assert that these allegations are part of the historical pejorative discourse evident in both the Global South and North where ‘welfare’ recipients are perceived as lazy and irresponsible.20 21

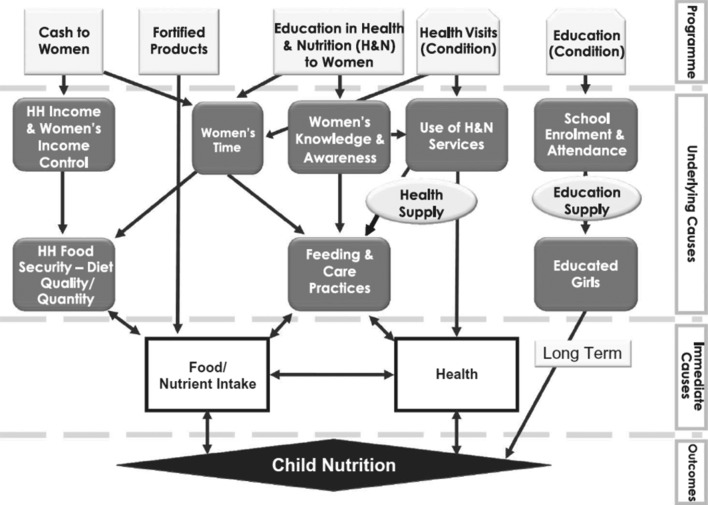

Recent analysis suggests that although the CSG may prevent further declines in child nutritional status, it fails to improve food security and child nutrition, not because it is misused but rather because it is small and diluted by ‘multiple uses and multiple users’.7 According to this evidence, the CSG is inevitably spent on several members of the household as well as the individual targeted beneficiary and on needs other than food, reflecting the multiple elements necessary to ensure child well-being. In a related context, Leroy et al 22 provide a framework for the different inputs needed to make child CTs effective in improving child well-being and nutrition (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms by which cash transfer programmes might affect child nutrition. Source: Leroy et al. 22

The Leroy et al 22 framework shows that giving CTs to women is one of five interventions needed in a coordinated package for supporting child nutrition and well-being. Other interventions include food, education in health and nutrition, healthcare facility visits and education more generally. The framework underscores two important points: first, that giving cash to women (rather than a male household head) leads to an increase in household income and women’s agency, which in turn leads to household food security and improvements in the quality and quantity of food that is available for children to eat and second, that important non-food inputs are also necessary to make cash work for child nutrition and well-being, in particular, women’s time, women’s knowledge about appropriate feeding, feeding and care practices, the availability and use of health and nutrition services and education services.

In the considerable body of work that exists on the role and effectiveness of the CSG in improving child outcomes, there are only a few qualitative studies that explore how it works in relation to other inputs necessary for child well-being and nutrition. There remains a gap in understanding how and what it takes to achieve well-being for CSG beneficiaries growing up in poor households in South Africa. This paper attempts to address this gap. With this framework as a reference point, we present findings from a qualitative study conducted to explore the role of the CSG in food security and child well-being in poor households in an urban and a rural setting in South Africa. Through these findings our paper interrogates how caregivers at a microlevel use the CSG and explores what is necessary to support child well-being in the context of the grant.

Methods

This qualitative study focused on an in-depth examination of the CSG and its role in child well-being and food security in an urban township in Langa, Western Cape Province and in a rural setting in Mt Frere, Eastern Cape Province.

Sampling frame

The sample of caregivers included in this study was drawn from households which participated in a longitudinal cohort study focusing on non-communicable diseases called the PURE Cohort. While the CSG is available for both female and male primary caregivers to access on behalf of eligible children, the majority of claimants (more than 95%) are women. Thus in this study all the participants were women. The study sample comprised a total of 40 in-depth interviews (20 in each site) with mothers or primary caregivers in receipt of the CSG for children under the age of 5 years. In addition, five focus group discussions with approximately eight members per group were conducted. The focus group discussions were conducted to gather a community level perspective on the role of the CSG in children’s diets and food security and how women were securing food for their children.

We chose to focus on children younger than 5 years because of the evidence that the first 5 years of life are the most important for nutritional outcomes that impact on childhood and beyond.

In some households, a family member was present during the individual interviews, in particular in a number of instances where we were talking with the biological mother of the index child, the grandmother would be present. In all instances, we ensured that the participant was happy for us to continue with the interview in the presence of another individual. Often the family member would be called on by the participant to corroborate or remind her of certain facts.

Table 1 presents a profile of the study participants in terms of average household size, CSG receipt status, employment and education levels in each site. The age range of the participants interviewed was 18–70 years, with six of the interviews being conducted with grandmothers who were the primary caregivers of the children selected. Marital status differed by site with fewer married respondents from Langa than Mount Frere. In Mount Frere, none of the respondents was employed, while in Langa, three participants were in formal employment. No respondent in any of the two sites had education levels beyond secondary school. In this manuscript, only data and findings from recipients are presented.

Table 1.

Profile of participants included in individual interviews (n=40)

| Mount Frere (n=20) | Langa (n=20) | |

| Household size range | 2–6 | 2–14 |

| Average household size | 4.3 | 5.6 |

| Age range of caregivers | 18–70 | 18–65 |

| Number of CSGs per household (range) | 1–5 | 1–7 |

| CSG caregivers in formal employment | 0 | 3 |

| Caregivers who have not completed secondary school | 17 | 6 |

| Caregivers who have completed secondary school | 3 | 14 |

| Relationship of caregiver to child | Mother (n=13) Grandmother (n=7) |

Mother (n=18) Grandmother (n=2) |

CSG, Child Support Grant.

Data collection and analysis

The lead author along with the study coinvestigators developed interview topic guides which were piloted in both Langa and Mt Frere and subsequently revised before being used to conduct individual and group interviews. In 2015, the lead author together with VR conducted all in-depth qualitative interviews and focus group discussions in the two sites. The interviews were conducted in isiXhosa as this was the main language spoken in both sites. When time and logistical circumstances permitted, WZM and VR would have a discussion after each interview, comparing notes on the themes they felt were emerging. Interviews were conducted until data saturation was achieved.

All data were analysed using Graneheim et al’s23 manifest and latent thematic content analysis methods.iii Data were transcribed and translated into English and checked against the original recording to ensure accuracy by independent transcribers. Following each interview, field notes were written to capture the context, home environment and non-verbal communication.iv These were analysed after each interview and used to guide further interviews where appropriate. The lead author read through each of the transcripts, noted initial thoughts and began manifest coding of the data. A list of all interviews and transcripts was captured in Excel, and manual copying and pasting of passages of text from Microsoft Word was undertaken during the categorisation of data. Although the lead author coded the data, there was extensive involvement of all authors in the analysis and interpretation of findings/results. Coauthors read the summaries of interviews and looked at some ‘raw’ transcripts to validate emerging themes and had several meetings, including two separate 2-day data analysis workshops to collectively undertake the analysis to ensure its reliability. Initial codes were grouped together into categories that were then further transformed into major themes. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comments. However, our ethics protocols encouraged interviewees to raise questions and interviewers were careful to reflect back and summarise comments throughout the interview to ensure accuracy of interpretation.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research question was informed by previous research which showed that recipients of the CSG were experiencing similar levels of food insecurity24 and declining child nutritional status. In conducting this research, we sought to understand participants’ experiences of securing food for their children in the context of the grant. The research question therefore speaks to participants’ experiences and priorities as it relates to issues that directly affect the well-being of their children and households.

Participants were not directly involved in the design of this study; however, previous research that we had conducted with similar communities on a related topic informed the study design.7 25 Patients were recruited for individual interviews and focus group discussions but they were not directly involved in recruitment.

Community meetings will be set up with participants in Langa to share study findings.

Ethics

Before each interview, the interviewers explained the purpose of the interview in detail and as far as possible ensured that participants understood what agreeing to participate in the study meant. Participants who agreed to participate signed a consent form. All participants were each given grocery shopping vouchers worth R100 (US$7.48) to compensate them for their time.

Results

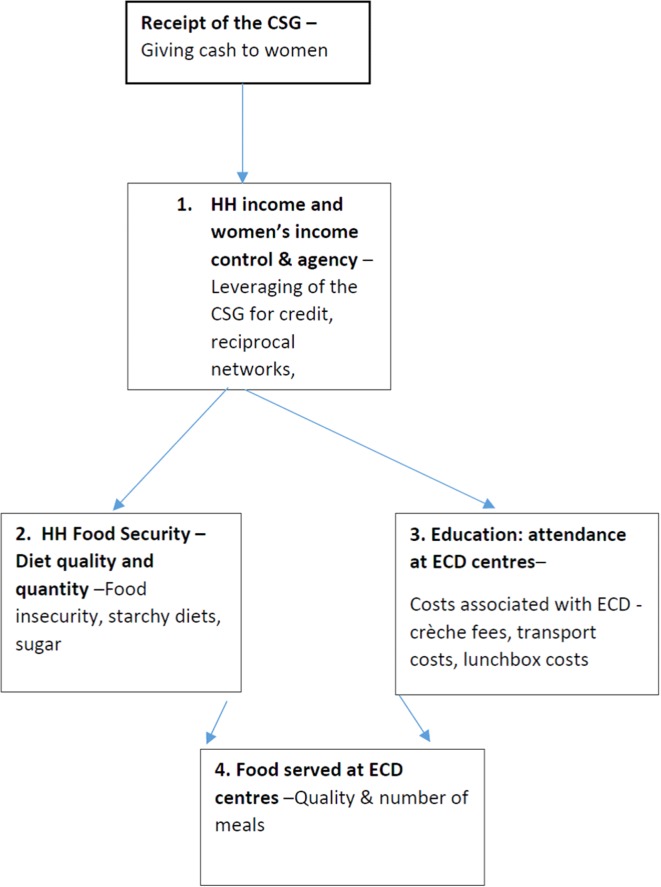

Respondents were asked to describe in detail their decision-making about using the CSG, in particular, how they used it to meet children’s needs and their experiences of accessing food in the context of receiving the grant. We have adapted Leroy et al’s 22 framework (figure 2) to identify the main themes emanating from the data about the different strategies caregivers engaged in to ensure food security and their children’s well-being through utilisation of the CSG. Using the adapted framework, we start off by presenting results related to: (1) Women’s income control and agency; followed by (2) Household Food Security; then (3) Education: attendance at early child development (ECD) centres and then while keeping with the theme on education and ECD centres, we present findings on Food served at ECD centres (4). Where possible we contrast findings from the rural site with those of the urban setting.

Figure 2.

Adapted conceptual framework for study findings. CSG, Child Support Grant; HH, Household; ECD, early child development.

Women’s income control and agency

Leroy et al’s22 framework conceptualises the placing of money in women’s control as a form of empowerment which leads to the availability of income in the household which women generally use for the good of the entire household. In this study, many caregivers stated that they pooled the CSG with other sources of income in the household (including other grants) and spent it on the needs of the household, with children’s needs being prioritised in many of the households. The bulk of the CSG went to needs related to direct food and school-related costs, though some was spent on household needs like utilities (electricity), toiletries and transport for job-seeking or healthcare.

‘… as I’m not working, sometimes I use the grant that my child gets to meet some of my needs like toiletries for myself and then I also use it for my child’s needs as well. When I go looking for a job I use some of the grant and I also use it for my child’s little things like lunch box things…because even the person I cohabit with is unemployed so I use that money… the grant… I buy electricity using the grant’ (CSG Recipient, Langa)

Different motivations and priorities informed the specific decisions caregivers made about what food to buy and what to feed their children. Sometimes these decisions were based on something as simple as wanting to make their children happy, even if this meant buying foods that were not deemed healthy. In other instances it was the caregiver’s support system that influenced what food the children ate. Often it was the presence of a grandmother in the household who either worked or received their own old age pension, which allowed children to have access to foods that they would otherwise not have.

‘And then I also buy chips… things that will make them happy; [such as] yoghurts……I buy a bag…of fifty [chips a month].’ (CSG Recipient, Langa)

‘…on Mondays she doesn’t usually have fruit because perhaps… there’s usually none here at home. Then I know on Thursday there’s no way there would not be [fruit]. On weekends she has plenty [of fruit] because it’s always available on weekends. Because when my mother goes to work on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, she brings back fruit for her.’ (CSG Recipient, Langa)

‘He likes eating yoghurt and she buys him Fritos chips, sometimes she also buys him Nik Naks, sometimes she buys him Kinderjoy (chocolate)… He eats them maybe three times a week because his grandmother buys them when she gets back from work’ (CSG Recipient, Langa)

Other times it was a combination of convenience, affordability and the perceived nutritious value of the food that influenced the choices caregivers made about what to feed their children.

‘However, the best bet is to use Instant Porridge just like I do…like my child leaves very early [for daycare], so I don’t have time to stand over the stove to cook very early in the morning while the transport is hooting outside, so Instant is very good for that… I can also say morvite is far better than any other porridge, it has vitamins……one has to be clever about what you feed the child, because things like meat are very expensive, we only eat it on Sundays……’ (CSG Recipient, FGD2, Langa)

‘Yes I’ve been feeding him anything that I think is good for him, like if it’s something like veg then I knew that I must grind it and then he will eat it’ (CSG Recipient, Mt Frere)

Respondents complained that the CSG by itself was ‘too small’ to feed their children and meet their other many needs within households with many competing demands on money.

‘They get money for clothing from this [CSG] money, on the other hand there is debt for food, then its school stuff, you see, others let’s say they go to school here in the location, others they use transport, all from the same money, [and even if there is] maybe another source of income, let’s say money from being a domestic worker, maybe they work a few days maybe two, and you find that it is not only this caregiver in the household, maybe there are four people here at the house and children, but this money is too little to be enough for here in the house you see, so its like that, then you are forced to make debt’ (CSG Recipient, FGD3, Langa)

Respondents specifically identified food as the main reason for taking out loans.

‘It is mostly debt for food…because there is that bread that they must have every day you have to buy it you see, no matter what bread has to be bought every day, even if there will be food there has to also be bread, even things to spread on the bread for the children, and porridges for the children everyday they have to have them, besides thinking ‘heee what is going to be eaten?’ first thing when they wake up in the morning, there must be something to eat in the morning’ (CSG Recipient, FGD3, Langa)

Some respondents felt that there was an expectation from family and community members for the grant to be able to meet all of the needs of their children. One mother who had two children and was pregnant with another and lived with her parents and older siblings talked about the pressure of needing to stockpile baby formula and other essentials in preparation for the unborn baby, in addition to meeting the needs of her existing children, so that she would not have to ask for help from her family whom she felt judged her spending of the grant:

‘I am trying to save all the time and I have to buy milk and put it aside, then I buy bottles and put them aside, because if I ask one of my family members to please buy me milk, then they will ask me if I do not get the grant for the children and what I do with the money, and yet the money that we get from grant does not do everything. Yes it does help out but it does not buy everything, then they will ask where the father of these children is and I know that the father needs work.’

Despite the small value of the CSG, many caregivers acknowledged that it allowed them to have greater leverage both for accessing credit systems and informal reciprocal networks. In this way while the small value of the grant undermined women’s agency on the one hand, on the other hand, its very presence enabled women to leverage it to access and maximise their social capital. Access to credit systems and informal reciprocal networks enabled recipients to use the grant in a flexible manner. Sometimes this took the form of accessing food on credit at informal outlets (spaza shops) when they ran out of food halfway through the month:

‘[at the Somaliansv’] … when I run out I can go back to them and ask for them to give me a 2 kg or a 1 kg….on credit of course. When I get paid I pay them back…[I] pay for all the things I’ve taken during the month. I take the R350 hamper, when it is finished I go again……they also know that on the 1st, M*** will pay them’ (CSG recipient, Langa)

Similarly, the CSG allowed caregivers to borrow from their neighbours in times of need, knowing that they would be able to repay them with the next grant pay out. In both the rural and urban study sites, borrowing could be in the form of cash or food or swapping food items. In all instances, including borrowing from a neighbour and relatives, mothers emphasised that whatever was borrowed had to be repaid at the beginning of the new month when people received their grants:

‘We ask around in the village, maybe someone you know, like a neighbour. You say Can you please give me some maize meal, you know that you are going to mix that with whatever you have in the house, maybe next time she will also need the same from you…we swap items -maybe you have mealie-meal or potatoes and maybe that is just what she needs’ (CSG recipient, Mt Frere)

…[if you borrow] yes you must reimburse them. Even when you buy [your own] 12,5 kg (of mealie-meal) you have to pay the person back for their mealie meal…yes, indeed no one works for anybody else… That is compulsory. Even now, I had borrowed some mealie meal from someone, I returned it in the morning’ (CSG Recipient, Mt Frere)

In summary, in this study, true to the framework, access to the CSG seemed to increase women’s income control and agency. However, teasing out the particular ways in which this small CT, often introduced in contexts of dire poverty and deprivation, linked to women’s agency proved complex and messy. The extent to which women’s income control of the grant translated to agency and influenced decision making around food was mediated—and sometimes limited—by a number of factors including: caregivers’ relationships and social networks, caregivers’ perceptions of what their children needed, the value of the grant and coping strategies.

Household food security

Mothers of CSG recipients provided detailed information about their spending of the CSG on food. Most primary caregivers in the study detailed feeding patterns that showed diets that were mostly starchy and sugary, with very little protein, vegetables, fruit and dairy. Mothers explained this as being a result of not having enough money.

‘They [children] eat whatever is in front of them. Porridge, rice, potatoes as well. Milk no, they only get it when I have money, then I’ll buy them then…right now they drink Rooibos [tea]’ (CSG recipient, Langa)

‘I don’t buy meat regularly. I buy it on the day we get the grant or sometimes after weeks, I mean it is not something common that we eat meat… (CSG recipient, Mt Frere)

Some food items, like sugar, though unhealthy, were regarded as highly valuable, as they made basic (typically plain) food, such as maize meal (pap) or soft porridge, palatable. The importance of sugar came out particularly strongly in the rural site.

‘…you must always have some sugar, we need to have sugar because when there is nothing else you can always just make pap and tea and the kids could just eat that and go to bed, they do not have a problem’ (CSG recipient, Mt Frere)

Households experienced regular food shortages and food often ran out before the end of the month. Caregivers demonstrated resilience and resourcefulness when they ran out of food and would often have to go to extraordinary lengths to obtain food for their children. Sometimes this meant leaving very young children in the care of their siblings to walk for miles to get food from relatives.

‘What I usually do when there is no food is to wash and leave this [15 month old] child with the younger children and then I walk to eNcinteni… I go to my sisters in-law -my husband’s brothers’ wives and come back with things I can cook for the kids, like potatoes, then I make the fire outside in the three-legged pot and I cook for my children and they go to bed having eaten’ (CSG recipient, Mt Frere)

Extreme levels of food insecurity in some households led caregivers to significantly change their diets; to sacrifice their share of meals and to dilute food in order to make it go further and spread it among more children in the household. Baked food items and using products from farmed animals were other common strategies, in the rural site.

‘when there is no money we often go to bed on pap and tea. We go to bed like that…when I was working we would have pap and meat and potatoes, we had good zishebo.vi Now it is difficult for us, we eat whatever is available…then sometimes I make homemade bread and we eat that with tea, … –we do all of this to make sure that we do not run out of food quickly……we must make sure that the food only runs out when it’s close to month end’ (CSG recipient, Mt Frere)

‘I sometimes try the [Maas] that’s sold [in shops], but I myself cannot eat it, even though it’s my favourite. I cannot eat it because, even [my youngest] and the others eat it. You realise that if you buy a 2 litre or a 5 litre [Maas], I think: If I make pap and maas for myself as well, this maas will get finished quickly…. but it’s supposed to last a few days [at least]. [So] perhaps I take…I take some spinach and cook that [for myself] … or I make sugar water, and I sleep having eaten’ (CSG Recipient, Mt Frere)

For children under 2 years old who were still thought to need formula milk, periods of food insecurity meant cutting out formula milk altogether, diluting it, reducing the frequency of bottle feeding or supplementing with cheap dairy products such as Maas (sour milk), a popular meal in Black African households.

‘[In her case A**] stopped having baby formula prematurely, because there was no money…the formula would get finished, you would see that [the formula]… that thickness is going down. While the child would be growing and needing more of it, it would be going down. So she would be eating formula which is more watery…So I got her used to my making sorghum porridge for her…Then I would take the baby formula, make it and pour it in here [with the porridge] so that she can eat something with milk in it.’ (CSG recipient, Mt Frere)

‘… since he’s older now, it [formula] lasts 2 weeks… Now, I normally feed him that in the morning… and then again in the evening;… During the day… I may give him even a lump of pap. Now I even buy Maas for him, I even buy Maas for him and then mix it with pap for him in the evening…… [the formula] lasts… 3 weeks because I would carefully plan its use.’ (CSG Recipient, Langa)

A number of respondents shared stories of extreme hardship as they negotiated their day to day lives and tried to provide food for their children with CTs as the only source of income in households where adults were either all unemployed or had precarious intermittent work. Caregivers shared stories about how they ‘made a plan’, in very dire circumstances, to ensure that their children had food and other needs met.

‘You know when you’re a woman, you make a plan. Mmm, to be a woman is to make a plan’ (CSG recipient, Mt Frere)

‘…when you milk the goats; if you’re going to feed [the milk] to her—before the milk curdles—you filter it…you cook it until it boils, then you put it into a flask. It’s very nourishing. You then take it and feed your infant. I mix it and mix it… so that the infant can finish that pap-like thing. And when her stomach is semi-full, I then take the baby bottle and feed [her], then she sleeps…’ (CSG recipient, Mt Frere)

In the few households where the CSG was not the sole source of income, particularly in households where either the caregiver worked or another close member of the household was employed, the child’s diet was markedly different, with more variation and choice. Notably, in both instances where this was the case the respondents were from the urban site, Langa.

‘She wakes up and eats porridge. Like… she prefers Kellogg’s; the one that’s porridge…Sometimes, though, it might be Weetbix. Or it might be… this thing… what’s that thing? That thing that’s like tasty wheat, but it’s also like…it’s similar to oats, but it’s also instant [porridge]. Those are the things that she prefers, which I make for her in the morning….[with] her milk…Nido; the 3 years+…(CSG Recipient, Langa) I buy sugar…, 5 kg…, I buy rice…, 5 kg…, I buy mielie meal, 5 kg…, I buy Milo; because they love Milo……So… in the morning they eat porridge and milk. I buy the milk in those six packs. It lasts half a month…… and meat…: mince meat, burger [patties], chicken, [and] viennas for sandwiches for when they go to school. And cheese…, and tomatoes, and… fruit. All types of fruit: apples, bananas, nectarines… I also buy potatoes of course. And onions and tomatoes for cooking. And spices.’ (CSG Recipient, Langa)

In summary, while the CSG was an important source of income, enabling caregivers to secure food for their children, it did not prevent food insecurity nor did it enable diverse, nutritionally adequate diets: households experienced regular food shortages and when there was food, the diets were often not nutritionally complete. During periods of shortage women engaged in different coping strategies to make food last longer. In households where the CSG was not the only source of income, diets were more varied.

Education: attendance at ECD centres

In Leroy et al’s 22 framework, education is one of the key interventions needed to improve child nutrition and well-being. About 90% of the primary caregivers we interviewed had their children attending ECD centres, commonly referred to as crèches. Costs ranged from R50 to R300 a month, though the majority of children in this study attended centres charging at the lower end of this range. Some of the centres were registered while others were informal, but it was difficult to differentiate between them as primary caregivers themselves did not typically have this information. All the centres served food, with most children either receiving breakfast and lunch or lunch only. A significant proportion of the CSG went towards crèche-related costs. In addition to direct fees this included, transport, lunchboxes and snacks, school bags and in the case of Mt Frere, chairs to sit on.

‘Like… this one’s [child support grant], I don’t even touch it; it goes to the crèche. I pay for her crèche [with the money]. It’s R230, yes, plus … they must also pay for snacks.’ (CSG Recipient, Langa)

‘[Crèche] is R180 [per month] this year, I don’t know next year if it will still be the same…and then money for transport is R140 [per month].’ (CSG Recipient, Langa)

Caregivers went to great lengths to obtain relatively expensive food items such as juice (concentrate), fat spread, eggs and snacks for their children to carry to school. This was the case even in the crèches that served food—caregivers still felt the need to send their children to school with a special packed lunch.

‘[the CSG] makes a difference. A small difference…but it makes one because, as I say to you, …in the morning when they go to school I give them an egg… and chips, and bread, a slice of bread…’ (CSG Recipient, Mt Frere)

‘Then you have to try to get some juice, you have to try to get some Rama [margarine]… if you don’t have eggs. [But] not the real Rama, these lesser Rama’s… you then spread, and spread, and spread [the Rama to make it go further], you put in the juice and the child leaves.’ (CSG Recipient, Mt Frere)

In summary, attendance at ECDs was common among the children enrolled in the study and the costs associated therewith were high, often exceeding the value of the CSG.

Food served at ECD centres

Even though all the crèches served food—as much as two meals a day in many centres—it was difficult to ascertain exactly what was served at the crèches. Many respondents could mention one or two items of food or meals that they thought their children were eating but had no detailed information of the food served for breakfast and lunch in a 5-day week.

‘I don’t know what mine is fed, I can’t lie, my child at one stage was fed Saldahna [tinned fish]…’ (CSG Recipient, FGD4)

‘There is usually breakfast…porridge… they said it is porridge…. Or otherwise, there is also a Morvitevii day. I’m not sure [what else] now.’ (CSG Recipient, Langa)

Some caregivers felt that the food served at crèches was not enough and that this was the reason they felt it necessary to send their children with additional food and why they had to have something ready for them to eat in the afternoon after crèche. It was not possible to accurately measure this since many respondents were not clear about what was served at creches or the portion sizes. Some caregivers did, however, observe that their children often came back from crèche thirsty and hungry.

‘They get food from the school…. No, it’s not enough of course. These are people who, as they come in, because they’re children, they say: ‘We’re thirsty, may we please have juice. We’re hungry… and so on ’ (CSG recipient, Mt Frere)

‘[they are served] rice, Saldahna (tinned fish), but it’s always a mixture of the two, sometimes its Soya, but where my child is schooling there are tinned Saldahna that are packed to the rafters, so I assumed that only a mixture of this Saldahna and rice is prepared and given to children’ (P2, CSG FGD2, Langa)

‘I felt that at school the food is not good at all. Some people preparing food at these creches aren’t trained at all and they aren’t careful with what they supply children at school with. My child doesn’t eat at school anymore she carries her food from home’ (P3, CSG FGD2, Langa)

In summary, all the ECDs served meals; however, caregivers were not clear about what they were served, nor were they satisfied that their children were receiving enough food at the crèches.

Discussion

This study contributes to the current relatively small evidence base of qualitative studies that seek to understand how CTs in low-income and middle-income settings play a role in child nutrition and well-being. Since this is a qualitative inquiry, findings cannot be generalised outside the study sites where the research was conducted. However, inferences can be drawn to broaden our understanding of how CTs affect child nutrition and well-being in low-income and middle-income settings.

Despite the original focus of the CSG on providing nutrition support to children in poor households, it is well known from literature that it takes many different inputs in addition to food to achieve good nutrition and general child well-being. Findings from this paper show how the various needs that children and households have, affect the strategies used and trade-offs made by caregivers in the utilisation of CSG.

Our results support evidence reported by others which demonstrate that while the CSG is an important nutrition-sensitive intervention, malnutrition is complex and requires a coordinated package of nutrition specific and nutrition sensitive interventions.7 Moreover, on its own, the CSG is clearly a small amount of money and therefore, irrespective of the multiple uses it is put to, has limited ability to provide even adequate quality nutritious food for a child. In the context of rising food prices as observed in 2016, even if the CSG was spent exclusively on nutritious food for beneficiaries alone, at its 2016 value (R350), it would ‘cover less than two-thirds of the minimum food needs of a young child (63%) or an older child (58%)’.7 The Pietermaritzburg Agency for Community Social Action (PACSA) Food Price Barometer for September 2016 calculated that the cost of a basic but nutritious food basket for a young child was R537.48 per month, way above the R350 value of the CSG at the time.26 The CSG is small and is diluted among ‘multiple users and multiple uses’7 18 as shown in this study. It can be argued that in a context of widespread poverty and high unemployment rates, it is impractical and unethical to expect caregivers to ring-fence expenditure of the CSG on child beneficiaries only.

The findings from this study confirmed Leroy et al’s framework,22 that increasing women’s income control facilitated attempts to mitigate food insecurity. Giving cash to women gave them control over a portion of the household income that only they had a say in how it should be spent. As reported in other studies,25 27 placing the CSG in the hands of women allowed them to leverage it to access reciprocal networks in the form of neighbours, relatives and access to informal credit when food ran out. The findings from this study indicate that these systems of reciprocity were intricate and elaborate mechanisms and were crucial life lines for communities with few other margins. At every turn, caregivers struggled: with food insecurity, where children had poor diets and mothers had to employ different strategies to ensure that there was food; in care practices, where the inadequacy of the grant made basics like soap a precious commodity; in accessing ECD services, where costs included fees, transport, lunchboxes and even in some cases, furniture and equipment.

Interventions such as ECD centres in South Africa hold a lot of promise in helping to meet the food needs of children from poor households. Ruel et al 6 emphasise the importance of ECD interventions with or without a nutrition component in tackling malnutrition. In South Africa, the ECD programme has a nutrition component and as shown in this study, it potentially makes up a significant amount of a child’s daily food intake. However, it is not well researched in terms of dietary quality and adequacy. Significantly however, though mothers prioritised early childhood education, it is important to note that it is not free. As indicated, the direct and indirect costs associated with attendance at ECD centres took up the whole grant in some households.

Taken together, our findings show that in the context of a non-comprehensive social security system caregivers constantly made trade-offs to meet essential needs—food versus education versus care practices. There was no evidence of misuse. Instead, in the context of fundamental, pressing and competing needs, rational decisions were made about how to spend this small CT. Evidence from studies that have interrogated the relationship between the CSG and misuse and perverse incentives refutes such claims.28–30

In their working paper on food security and social grants published in 2017, Devereux and Waidler7 point out that while social grants in South Africa are an important source of income for poor households, the amounts they transfer to households need to rise and should be linked to the amount of money needed to buy a nutritious food basket. The authors further recommend that social protection provision should be framed within ‘cash plus’ models that are linked to broader non-cash services and inputs such as health, education, social services and sanitation and the promotion of appropriate nutrition and hygiene practices. Current interest in ‘cash plus’ models arises out of the growing recognition that it takes more than cash or a narrow focus on food to improve child well-being.31 In South Africa, ‘plus’ components such as free education or subsidised ECD services are in place, but as this paper has shown, access is often inequitable and still comes with hidden costs.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that caregivers make rational decisions and employ different strategies that ultimately serve—even if in a small, limited way—the actual goals of the CSG: child well-being and nutrition. The recent public furore around threats to the disbursements of social grants in South Africa was proof once again of how indispensable CTs such as the CSG have become to the survival of households in South Africa. It is indisputable that the CSG plays an important role in childhood poverty alleviation efforts in South Africa. However, it is not a panacea. This paper has presented results which confirm previous findings about the inadequacy of the CSG to meet its goal of providing support for nutrition. However, in a context of high unemployment rates, soaring food prices, rising cost of living and the lack of coordination between other nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific interventions, their efforts were undermined by a CT that was too small in value to make a meaningful difference to child nutrition. Thus, while the CSG is important, much more emphasis should be placed on parallel structural solutions that are important in ensuring good nutrition outcomes and well-being. These would include access to free, quality ECD services that provide adequate nutritious meals, access to basic services that impact on nutritional outcomes such as housing with adequate water and sanitation services and the promotion of appropriate feeding, hygiene and care practices. Such measures would form part of a coordinated response to improve child well-being, consisting of a package of nutrition sensitive and nutrition specific interventions, in addition to raising the value of the CSG and creating a comprehensive social security system in South Africa that provides for people through the life course.

Further research, both qualitative and quantitative, is needed to understand how nutrition-sensitive non-food inputs such as ECD services and care arrangements work to impact on child nutrition and well-being within a ‘cash plus’ framework.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the caregivers and their families for their contribution to this study. We also wish to thank Professor Stephen Devereux for reading the first draft of this manuscript and providing insightful comments that helped to strengthen it.

Footnotes

At the time of data collection.

This is a so-called ‘soft condition’ because on paper it is said to not be a condition for continued receipt but rather a mechanism for identifying and providing support to children who are struggling to stay in school, but in practice when a CSG beneficiary drops out of school, they cease to receive the grant until they return to school.

A process where each transcript is first read through, then manually coded and repeated codes are categorised into themes.

Non-verbal communication such as quietly crying, sighs, eye-contact avoidance.

The term ‘Somalians’ refers to spaza shop owners who are Somalian foreign nationals.

Relish used to accompany a starch dish.

Sorghum sweetened instant porridge.

Contributors: All authors conceptualised and designed the study. WZ-M and VR conducted the interviews. Data were coded and analysed by WZ-M, and the coding and analysis were checked by VR, TD, DS, RSu and RSw. WZ-M wrote the first draft of the manuscript and thereafter all coauthors made inputs on all drafts of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was financially supported through the DST/NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: South African Medical Research Council Ethics Committee (EC036112105).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The study data comprise audio recordings, transcripts, transcript summaries and coded analysis. The coded analysis is available for reviewers should they wish to access it. We are unable to make the audio recordings and transcripts available as we did not seek permission for this from participants at the start of the study when we collected data.

References

- 1. Hendriks S. Food security in South Africa: Status quo and policy imperatives. Agrekon 2014;53:1–24. 10.1080/03031853.2014.915468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ruel M, Hoddinott J. Investing in early childhood nutrition. Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Case A, Paxson C. Causes and Consequences of Early Life Health NBER Working Paper Series no. 15637. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. May J, Timæus IM. Inequities in under-five child nutritional status in South Africa: What progress has been made? Dev South Afr 2014;31:761–74. 10.1080/0376835X.2014.952896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rumsby M, Richards K. Unequal portions - ending malnutrition for every last child. London: Save the Children Fund, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ruel MT, Alderman H. Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: how can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet 2013;382:536–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60843-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Devereux S, Waidler J. Why does malnutrition persist in South Africa despite social grants? Food Security SA Working Paper Series No.001. South Africa: DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. May J. Bailey C, Why child malnutrition is still a problem in South Africa 22 years into democracy in South Africa. South Africa: The Conversation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hall K, Sambu W, Berry L, et al. : Delany A, Jehoma S, Lake L, South African Early Childhood Review 2016. Cape Town: Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town and Ilifa Labantwana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. South Africa Demographic Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report 2017: Statistics South Africa; Pretoria: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bastagali F. Cash transfers: what does the evidence say? A rigorous review of programme impact and of the role of design and implementation features. London: Overseas Development Institute, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Manley J, Gitter S, Slavchøvska V. How effective are cash transfer programmes at improving nutritional status: A rapid assessment of programmes’ effects on anthropometric outcomes. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lund F. Changing Social Policy. Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aguero JM, Carter MR, Woolard I. The Impact of Unconditional Cash Transfers on Nutrition: the South African Child Support Grant: Centre for Global Development, 2006. http://www.cgdev.org/doc/events/11.07.06/unconditional%20cash%20transfers.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Samson M, Lee U, Ndlebe A, et al. The Social and Economic Impact of South Africa’s Social Security System. Pretoria: Commissioned by the Directorate: Finance and Economics, Department of Social Development, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pienaar PL, Von Fintel DP. Hunger in the former apartheid homelands: Determinants of converging food security 100 years after the 1913 Land Act Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers 26/2013. University of Stellenbosch: Cape Town, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Battersby J. The State of Urban Food Insecurity in Cape Town: Urban Food Security Series. Kingston and Cape Town: Queen’s University and AFSUN, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coetzee M. Finding the Benefits: Estimating the Impact of The South African Child Support Grant. South African Journal of Economics 2013;81:427–50. 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2012.01338.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mpike M, Wright G, Rohrs S, et al. Common concerns and misconceptions: what does the evidence say? : Jehoma S, Delany A, Jehoma S, Lake L. South African Child Gauge. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2016:55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fraser N, Gordon L. A Genealogy of Dependency: Tracing a Keyword of the U.S Welfare State: The University of Chicago Press, 1994:309–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mead L. The New Politics of Poverty: The Non-working Poor in America. US: Basic Books, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leroy JL, Ruel M, Verhofstadt E. The impact of conditional cash transfer programmes on child nutrition: a review of evidence using a programme theory framework. J Dev Effect 2009;1:103–29. 10.1080/19439340902924043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004;24:105–12. 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patel L. The gender dynamics and impact of the Child Support Grant in Doornknop, Soweto. Johannesburg: Centre for Social Development in Africa University of Johannesburg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zembe-Mkabile W, Surender R, Surrender R, Sanders D, et al. The experience of cash transfers in alleviating childhood poverty in South Africa: mothers' experiences of the Child Support Grant. Glob Public Health 2015;10:834–51. 10.1080/17441692.2015.1007471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith J, Abrahams M. PACSA Food Price Barometer Annual Report 2016. Pietermaritzburg: Pietermaritzburg Agency for Community Social Action, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27. du Toit A, Neves D. Informal Social Protection in Post-Apartheid Migrant Networks: Vulnerability, Social Networks and Reciprocal Exchange in the Eastern and Western Cape. South Africa: Brooks World Poverty Institute, 2009. www.manchester.ac.uk/bwpi. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Makiwane M, Udjo E. No proof of ’child farming' in awarding of child support grants. Human Science Research Council Review 2007;5:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Makiwane M. The child support grant and teenage childbearing in South Africa. Dev South Afr 2010;27:193–204. 10.1080/03768351003740498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Surender R, Noble M, Wright G, et al. Social assistance and dependency in South Africa: an analysis of attitudes to paid work and social grants. J Soc Policy 2010;39:203–21. 10.1017/S0047279409990638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roelen K, Delap E, Jones C, et al. Improving child wellbeing and care in Sub-Saharan Africa: The role of social protection. Child Youth Serv Rev 2017;73:309–18. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.12.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.