Abstract

South Africa’s MomConnect mobile messaging programme, which aims to promote safe motherhood and improve pregnancy outcomes for South African women, includes a helpdesk feature which allows women registered on the system to ask maternal and child health (MCH)-related questions and to provide feedback on health services received at public health clinics. Messages sent to the helpdesk are answered by staff located at the National Department of Health. We examined event data from the MomConnect helpdesk database to identify any patterns in messages received, such as correlation of frequency or types of messages with location. We also explored what these data could tell us about the helpdesk’s effectiveness in improving health service delivery at public health clinics. We found that approximately 8% of registered MomConnect users used the helpdesk, and that usage was generally proportional to the use of antenatal care (ANC) services in provinces (as indicated by number of ANC first visits and number of MomConnect registrations), except in two provinces. Language, category and key topics of helpdesk messages were correlated with provinces. Most users accessed the helpdesk to seek maternal information, and where feedback about health services was provided, there were significantly more compliments than complaints. The MomConnect helpdesk is an important resource providing expectant mothers and mothers of infants with an interactive option for accessing MCH-related information—above that included in the standard MomConnect messages—and advances achievement of the health goals of the MomConnect programme.

Keywords: health education and promotion, maternal health

Key questions.

What is already known?

Despite being an unadvertised resource, the MomConnect helpdesk is heavily used, receiving an average of over 252 messages per day.

What are the new findings?

Helpdesk usage aligns with the proportion of pregnant women registered on MomConnect and antenatal care first visits per province.

Most users access the MomConnect helpdesk for maternal information rather than for discussing health services received.

What do the new findings imply?

Correlations of key topics and languages and provinces could help identify specific needs in different geographical areas of South Africa, and could allow for targeted or customised messages that can better address mothers’ needs in specific locales.

Longer response times to Zulu and Xhosa messages, and during the holiday period, suggest the need for more Zulu-speaking and Xhosa-speaking helpdesk staff and for one to two helpdesk staff to work during the holiday period to improve response rates.

Introduction

Mobile messaging programmes that provide health information messages to target populations have shown success in improving health outcomes in areas of maternal and child health (MCH), and HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy adherence.1–3 Less is known, however, about the effectiveness of mobile health (mHealth) programmes that provide two-way communication platforms.4 Two-way communication systems can allow target populations to receive and respond to important health information, a potentially useful innovation in low-resource or sparsely populated settings.

Health hot lines are an example of two-way communication systems that have started to emerge in low-resource settings.5 Chipatala Cha Pa Foni, a programme in rural Malawi that sent health ‘tips and reminders’ via voice and text messages and offered a toll-free hot line for clients to call for additional MCH information, is credited with increased home-based management of common health problems.6 7 The mCenas! programme in Mozambique—which connected youths to an interactive short message service (SMS) texting system with ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ (FAQs) and a hot line for reproductive health information—was found to increase knowledge of contraceptive methods and reported contraceptive use among some youths.8 9 The mCenas! programme’s target population preferred receiving automatically sent information via SMS to using the two-way communication option.8 However, it did not report how frequently the two-way communication option was used or why.

South Africa has a rich tradition of helplines and call centres for users to access information. Two examples include the National AIDS Helpline and Childline, South Africa’s crisis hot line. Both are toll-free call services available in multiple languages, and provide anonymous and confidential counselling and referral services.

Drawing on South Africa’s history with interactive public services and similar health initiatives in the region, South Africa’s National Department of Health (NDOH) established a helpdesk feature as part of its MomConnect programme, which aims to promote safe motherhood and improve pregnancy outcomes for South African women. The MomConnect helpdesk serves a similar purpose to that of a hot line or call centre. Since its launch in August 2014, it has provided mothers with a two-way SMS platform to ask MCH-related questions. Mothers can also send feedback through the helpdesk, such as complaints or compliments, on antenatal care (ANC) services they receive. Helpdesk staff respond to FAQs with 1 of 114 custom responses, also via SMS. The helpdesk manager, a registered nurse, also responds with a more personalised SMS or phone call to selected non-FAQ messages. If the message contains an urgent health matter or can be better addressed by a medical professional, then the woman is advised to visit, or seek more information, at her nearest health clinic. Complaints about service delivery that are sent to the helpdesk trigger more extensive follow-up.

Despite the growing evidence that mHealth programmes are effective in improving health,10 literature also points out that the contribution of mHealth programmes is not comprehensively understood. Current evidence of the impact of mHealth programmes is relatively weak, and further evaluations are needed to better guide future mHealth programming decisions and implementation.11–13 For MomConnect, various studies have examined operational aspects of the programme to identify opportunities for improvement during the early stages of implementation.14 One review of the helpdesk that focused on the impact of complaints on the supply side of the health system showed how these complaints resulted in identification of drug and vaccines stock outs and ultimately resulted in systemic improvements within the drug management system.15 Yet, there is still limited understanding of how mothers are using the MomConnect helpdesk and of its potential contribution to improving health outcomes.

As a first step towards filling this knowledge gap, we analysed nearly 3 years of MomConnect helpdesk data to identify patterns in the volume and content of messages, as well as response time to complaints, over time and across geographical areas. Findings from these analyses were intended to inform understanding of how the MomConnect helpdesk is used by registered women, an essential step to improving how the programme serves women. Data for helpdesk messages received between 13 August 2014 and 31 March 2017 were extracted from the MomConnect District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS 2) database. These data were cleaned for duplication and normalised for ease of analysis. The data set included user unique identifiers, the content of each message, receipt and response dates, the message categories and the province in which the clinic, the woman registered at, was located. References to ‘province’ in this paper indicate that the message came from a mother who registered at an antenatal clinic within the province, not necessarily that the mother continued to access antenatal services or live in that province. The data set did not include patient-level data, therefore we did not look at associations between individual characteristics (such as age and language) and helpdesk utilisation.

MomConnect helpdesk message data in DHIS 2 do not include all messages that are received by the helpdesk, only those that the helpdesk responded to. For example, incoming messages that exceeded the maximum SMS length of 160 characters were received as multiple messages by the helpdesk; the helpdesk only responded to one of the messages in the string of messages. Similarly, helpdesk staff could have sent one response to address multiple messages from the same user. There were also messages that did not require a response from the helpdesk. It is possible that biases were introduced as a result, and therefore, findings from this study may not be representative of all helpdesk messages. Additionally, there was a change in the helpdesk technology platform and protocol in October 2016. This could have introduced a confounder.

Descriptive analysis of helpdesk event data examined the frequency and proportion of message category, language, geographical origin (province) and response times. Bivariate analysis was conducted to identify patterns with the helpdesk messages. Pearson’s χ2test was used to test significant associations between message category and province. A one-way analysis of variance test was used to see if there were significant differences in response time between provinces and different months of the year. Multinomial logistic regression and pairwise comparisons of means were used to further examine relative probabilities for those variables with statistically significant associations or differences. All analyses were completed in Stata V.14.1, except for some descriptive statistics that were completed in Excel.

helpdesk utilisation

There were 253 309 MomConnect helpdesk messages recorded in DHIS 2 between 13 August 2014 and 31 March 2017. The final data set, after removing duplicates, had 241 715 unique messages, with 95 288 unique users. Almost half (48%) of the users sent more than one message. Messages from users that sent multiple messages made up 80% of all messages.

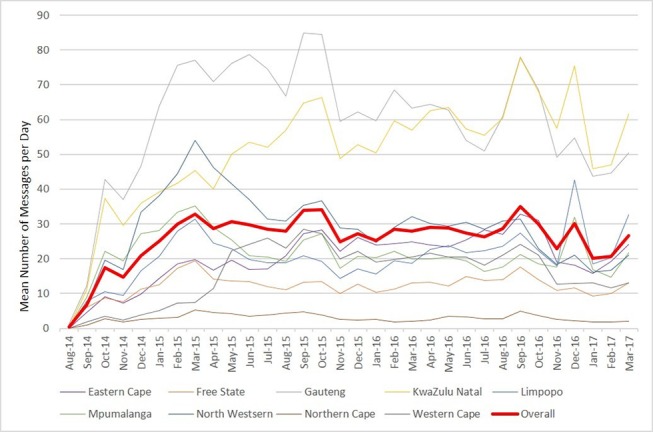

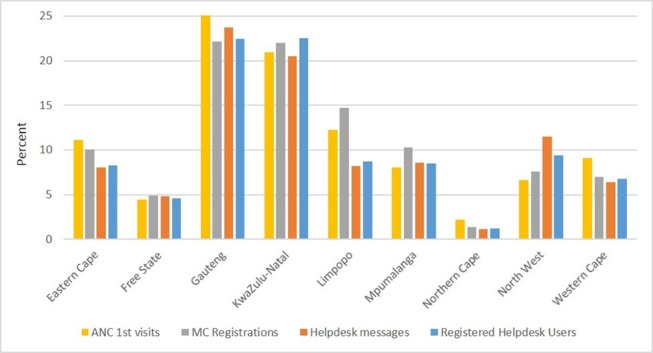

Figure 1 illustrates the mean number of messages received per day, by province, over time. The mean number of messages received per day was 252 (SD=162) messages, including Saturdays and Sundays. March 2015, September 2015, October 2015 and September 2016 had the highest number of helpdesk messages. After an initial rise, the number of messages stabilised, with a slight decline from November 2016 to February 2017. The low volume of helpdesk messages during November to January months contributes to the variation in volume of messages, but is reasonable, as this period corresponds with holiday months. Approximately 8% of all registered MomConnect users used the helpdesk feature. Helpdesk utilisation was highest from users in Gauteng (23.8%) and Kwazulu-Natal (20.5%) provinces and lowest from those in the Northern Cape (1.2%) (table 1). helpdesk utilisation over time and by province aligned with trends in the proportion of pregnant women registered on MomConnect and the proportion of pregnant women attending their first ANC clinic visit in the public sector (figure 2). For example, Gauteng also had the highest percentage of MomConnect registrations (22.1%) and ANC first visits (25.2%). Limpopo and North West provinces were exceptions. Limpopo had a relatively low share of both helpdesk users and helpdesk messages, despite having the third highest percentage of MomConnect registrations and ANC first visits. The proportion of helpdesk messages from North West Province was unusually high at 11.5%, but with only 7.6% and 6.6% of MomConnect registrations and ANC first visits, respectively. It is unclear why there was proportionately low helpdesk activity among MomConnect users in Limpopo and high helpdesk activity among MomConnect users in North West.

Figure 1.

Mean number of incoming helpdesk messages per day, by month, by province.

Table 1.

Frequency and percent of helpdesk messages by province

| Province | Frequency (number of messages) |

Percent of messages |

| Eastern Cape | 19 447 | 8.1 |

| Free State | 11 731 | 4.9 |

| Gauteng | 57 406 | 23.8 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 49 472 | 20.5 |

| Limpopo | 19 785 | 8.2 |

| Mpumalanga | 20 660 | 8.6 |

| Northern Cape | 2836 | 1.2 |

| North West | 27 755 | 11.5 |

| Western Cape | 15 398 | 6.4 |

| Other* | 17 225 | 7.1 |

| Total | 241 715 | 100 |

*Helpdesk messages labelled as ‘Other’ are helpdesk interactions from users who are subscribed to but not registered on MomConnect and therefore do not have a ‘home’ province.

Figure 2.

Relative proportions of antenatal first visits, MomConnect (MC) registrations, helpdesk messages and registered helpdesk users, by province.

More generally, we found a surprisingly high number of helpdesk messages, given that the helpdesk feature is not specifically advertised. First-time registrants on the platform are invited to dial an unstructured supplementary service data (USSD) code to access other services, which include the ability to send messages to the helpdesk. Mothers are not informed about the helpdesk during registration and do not receive reminders about the availability of this service beyond the initial invitation. Comparably, in Zanzibar, a mobile phone intervention that provided MCH information via SMS and airtime vouchers for mothers (n=1311) to call health providers, found that 30% of mothers used the vouchers to call their providers for additional information in emergency and non-emergency situations.16 No other information was provided on the nature of the calls or effectiveness of the two-way communication component of the Zanzibar study. Participation in the two-way communication component of the intervention in Zanzibar was much higher than MomConnect registrants’ use of the helpdesk. However, it is important to note the larger scale of the MomConnect programme, the unadvertised nature of the MomConnect helpdesk and that vouchers are not provided to mothers.

Reasons for helpdesk use

The helpdesk interface (called CasePro) allows helpdesk staff to group the messages into eight categories: clinic code (to indicate a facility code needed to be assigned or corrected), complaints, compliments, message switch, opt out, prevention of mother-to-child transmission questions, ordinary questions and ‘Other’. Helpdesk messages in the DHIS 2 data set included the category variable. The majority of the messages (78.5%), were questions. The ‘Other’ category made up the second largest proportion (13.2%) and included spam, unable to assist, unclassified, duplicate and language switch messages. Table 2 provides details of the proportions of message categories by province. A χ2 test revealed a significant association between message category and province (P<0.001).

Table 2.

Proportions of message category by province

| Question | Clinic code | Complaint | Compliment | Message switch | Opt out | Other | PMTCT | All messages | |

| Province | n=1 75 704 | n=154 | n=1824 | n=8131 | n=5577 | n=1972 | n=29 556 | n=1307 | n=223 626 |

| Eastern Cape | 8.7 | 9.1 | 6.8 | 8.7 | 5.5 | 7.3 | 9.3 | 12.6 | 8.7 |

| Free State | 5.3 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 5.2 |

| Gauteng | 25.6 | 26.0 | 26.4 | 30.3 | 20.5 | 24.5 | 25.2 | 23.6 | 25.6 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 22.3 | 27.3 | 16.0 | 19.1 | 36.0 | 21.7 | 18.8 | 27.2 | 22.0 |

| Limpopo | 8.1 | 5.8 | 15.6 | 9.9 | 16.0 | 14.7 | 10.9 | 8.3 | 8.8 |

| Mpumalanga | 9.2 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 9.6 | 10.9 | 9.2 |

| North West | 12.7 | 9.7 | 14.4 | 10.3 | 4.7 | 8.2 | 12.7 | 8.5 | 12.4 |

| Northern Cape | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.3 |

| Western Cape | 7.0 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 7.8 | 3.9 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 3.6 | 6.9 |

PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

Compliments and complaints comprised approximately 4% of the messages, with a higher relative probability of compliments from Gauteng than most other provinces. It is encouraging that there were more compliments than complaints submitted to the helpdesk; there were roughly four compliments to every complaint. The ratio of compliments to complaints in the DHIS 2 data set was slightly lower than previous analysis of data obtained from the helpdesk ticketing interface (called CasePro).15 As a whole, the small proportion of complaints and compliments shows that the primary value of the helpdesk to mothers is the ability to interactively seek maternal information that may not be included in the standard MomConnect message set.

helpdesk questions

For this analysis, messages that were categorised as a question and were in English (n=1 24 328) were further coded into 1 of 12 key topics. Key topics were systematically derived from the list of responses for FAQs and the stage-based maternal messages. The code list, including keywords for each topic, was finalised in consultation with the helpdesk manager. A key topic was identified in 65 364 helpdesk messages. These are summarised by province in table 3. It is important to note that misspellings, abbreviated language and slang that are often used when texting would have prevented keywords from being identified in the messages. We suspect this is the main reason why keywords were not identified in half of the English messages.

Table 3.

Proportion of key topics by province

| Baby | Breast feeding | Clinical | General | Headache | HIV | Labour | Nausea | Nutrition | Proteinuria | Support | Vaginal | Total categorised questions | |

| Province | n=5241 | n=5529 | n=5790 | n=6906 | n=1809 | n=7663 | n=8311 | n=1799 | n=7880 | n=724 | n=6930 | n=6783 | n=65 365 |

| Eastern Cape | 5.9 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 7.6 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 5.4 | 6.6 |

| Free State | 5.4 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 5.3 |

| Gauteng | 37.0 | 35.2 | 29.1 | 33.1 | 33.1 | 33.1 | 34.3 | 33.8 | 33.0 | 28.7 | 32.4 | 34.0 | 33.4 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.3 | 14.1 | 10.1 | 15.2 | 12.8 | 10.7 | 12.8 | 10.1 | 14.7 | 11.8 | 13.1 |

| Limpopo | 8.1 | 7.9 | 11.4 | 9.9 | 10.5 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 9.1 | 10.9 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 9.9 |

| Mpumalanga | 10.3 | 10.3 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 11.1 | 9.8 | 9.3 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 10.5 | 10.4 | 10.1 |

| North West | 15.5 | 16.1 | 15.6 | 13.4 | 16.5 | 13.5 | 15.3 | 15.5 | 14.8 | 19.1 | 12.9 | 15.6 | 14.8 |

| Northern Cape | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Western Cape | 4.8 | 5.1 | 7.6 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 4.4 | 6.0 | 7.1 | 5.2 | 8.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 5.9 |

There was a significant association between key topics of messages and province (P<0.001). Questions coded as ‘baby’ (questions about the baby) and ‘breastfeeding’ were less likely to come from Limpopo, Northern Cape and Western Cape than Gauteng. HIV-related questions were more likely to come from KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga than Gauteng, both by approximately 20%. ‘Support’ questions that indicated need for social or psychological support (eg, domestic violence, depression or seeking support groups) were 25% more likely to come from KwaZulu-Natal than Gauteng.

We suggest that the standard categories in the current helpdesk system be expanded to include more specific topics. This can allow for a more comprehensive understanding of issues that mothers are inquiring about. For example, we found that HIV-related queries were more likely from mothers that registered at facilities in KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga. This corresponds with higher HIV prevalence in the two provinces,17 and also suggests the need to address knowledge gaps around HIV and pregnancy. The correlations of key topics and languages and provinces could help identify specific needs in different geographical areas of South Africa, and could allow for targeted or customised messages that can better address mothers’ language needs in specific locales.

helpdesk languages

Messages sent to the helpdesk could have been in any language used in South Africa. However, SMS responses back to mothers were only in English. Google Sheets’ ‘detect language’ function was used to identify the language of the incoming message and create the language variable. One limitation of the study is that the study team could not verify that the correct language was accurately detected for all messages.

The most common languages from the data set were English, Zulu, Xhosa, Sesotho and Afrikaans. Languages that represented <1% of the messages were categorised as ‘Other.’ Two-thirds (65%) of the messages were in English. Zulu was the next most frequent language at 17%, followed by Xhosa at 6%, Sesotho at 5% and Afrikaans at 2%. As one would expect, the language of incoming messages was significantly related to province (P<0.001). The correlation between the language and origin of the messages were internally validated; Zulu-speaking communities are common in KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga, Afrikaans-speaking communities in the Northern Cape and Western Cape, Sesotho-speaking communities in Free State and Xhosa-speaking communities in Eastern Cape. See table 4 for details on the per cent of languages, by province. Notably, when comparing languages between KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng, the relative probability that a message would be from KwaZulu-Natal was more than double when the language was in Zulu. However, the relative probability that a message would be from Gauteng increased five times when the message was in English.

Table 4.

Proportion of message language, by province

| Afrikaans | English | Other | Sesotho | Xhosa | Zulu | |

| Eastern Cape | 2.5 | 48.3 | 8.2 | 0.9 | 34.1 | 6.1 |

| Free State | 1.0 | 66.1 | 3.7 | 24.5 | 1.2 | 3.5 |

| Gauteng | 0.4 | 82.6 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 8.1 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 0.1 | 37.6 | 7.2 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 52.2 |

| Limpopo | 0.2 | 79.1 | 6.8 | 9.4 | 0.8 | 3.6 |

| Mpumalanga | 0.3 | 70.2 | 4.6 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 21.4 |

| North West | 0.7 | 77.1 | 4.3 | 14.7 | 1.9 | 1.3 |

| Northern Cape | 25.0 | 58.6 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Western Cape | 15.8 | 56.0 | 6.1 | 0.6 | 19.1 | 2.4 |

| Total | 1.9 | 64.6 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 16.9 |

Response to helpdesk messages

The average time for helpdesk staff to respond to all messages was 0.65 (SD=2.3) days, or approximately two-thirds of a day. However, this reflects that messages received on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays were not responded to until Monday. The response times also varied by month, with longest response times during December 2015, and January 2016 and 2017, likely due to staff being on holiday during these months. There was a significant difference in response time between languages (P<0.001). Messages in Zulu and Xhosa had the longest mean response times, at 0.84 (SD=2.6) and 0.82 (SD=2.2) days, respectively. Messages in English and Sesotho had the shortest response times, at 0.61 (SD=2.2) and 0.62 (SD=2.3) days, respectively. A pairwise comparison of mean response times supported the significantly longer response time for messages in Zulu and Xhosa when compared with messages in English (P<0.001 for both Zulu and Xhosa), Sesotho (P<0.001 for both) and Afrikaans (P=0.028 for Zulu only).

Importantly, this study identified potential staffing gaps, such as the need for more Zulu-speaking and Xhosa-speaking staff given the comparatively long response times for Zulu and Xhosa messages. The majority of messages were in English and staff were able to quickly respond to English messages, compared with those in Zulu and Xhosa. Currently, only one helpdesk staff member speaks Xhosa. Additionally, keeping one to two helpdesk staff working during the holiday period could improve response rates during this time.

There exists early evidence of the helpdesk’s unique position to detect systemic flaws in the health system,15 which was possible because the helpdesk is positioned at the national office. This unique placement of the helpdesk is important for enabling the NDOH to strategically identify and address other national and provincial-level gaps in the health system. Additionally, the NDOH may also need to consider alternate strategies to effectively address changes at the facility level, since addressing issues at individual facilities likely requires a much higher level of effort from staff.

Conclusion

The MomConnect helpdesk is a valuable feature of the MomConnect programme, providing registered women with the ability to interact with live staff who can answer MCH-related questions. Despite it being an unadvertised resource, use of the helpdesk is high, with an average of 252 messages received per day during the period analysed. Messages received were strongly correlated with the utilisation of ANC services in provinces. Although one of the helpdesk’s stated aims is to provide a feedback loop for women in order to improve maternal health services at public health clinics, the majority of women writing in to the helpdesk during this period sought information on maternal health, rather than providing feedback about services received at specific public health facilities. Where feedback was provided, a significant proportion was positive rather than negative.

The high usage of the MomConnect helpdesk shows that women are eager to learn more about maternal health beyond what is provided in the standard MomConnect message set. By providing registered women with a mechanism for interactively seeking such information, the MomConnect helpdesk is contributing to the MomConnect programme’s overall aim of improving maternal health outcomes for women in South Africa.

Acknowledgments

The support provided by John Snow, Inc. (JSI) in the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded MEASURE Evaluation Strategic Information for South Africa (MEval-SIFSA) project to enable this publication is acknowledged with gratitude.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: KX developed the study design, extracted, cleaned and analysed the data, and contributed to the writing and multiple reviews of the manuscript. JK reviewed the study design, conducted a literature search and contributed to the writing and multiple reviews of the manuscript. JS provided important context and background information and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: MEASURE Evaluation-Strategic Information for South Africa is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through associate award AID-674-LA-13-00005 and implemented by the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in partnership with ICF International; John Snow, Inc.; Management Sciences for Health; Palladium; and Tulane University. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US government.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Conserve DF, Jennings L, Aguiar C, et al. . Systematic review of mobile health behavioural interventions to improve uptake of HIV testing for vulnerable and key populations. J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:347–59. 10.1177/1357633X16639186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. . Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376:1838–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61997-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coleman J, Bohlin KC, Thorson A, et al. . Effectiveness of an SMS-based maternal mHealth intervention to improve clinical outcomes of HIV-positive pregnant women. AIDS Care 2017;29:7–897. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1280126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee SH, Nurmatov UB, Nwaru BI, et al. . Effectiveness of mHealth interventions for maternal, newborn and child health in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2016;6:010401 10.7189/jogh.06.010401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ivatury G, Moore J, Bloch A. A Doctor in Your Pocket: Health Hotlines in Developing Countries. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 2009;4:119–53. 10.1162/itgg.2009.4.1.119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Innovations for MNCH. Bridging women and children to better health care: maternal newborn and child health access through mobile technology in Balaka District, Malawi. 2013. http://innovationsformnch.org/uploads/publications/ICT_for_MNCH_2013_Project_Brief_10.02.13_short.pdf

- 7. Obasola OI, Mabawonku I, Lagunju I. A Review of e-Health Interventions for Maternal and Child Health in Sub-Sahara Africa. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:1813–24. 10.1007/s10995-015-1695-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mendoza G, Levine R, Kibuka T, et al. . mHealth Compendium, Volume Four. Arlington, VA: African Strategies for Health, Management Sciences for Health, 2014:18–19. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feyisetan B, Benevides R, Jacinto A, et al. . Assessing the Effects of mCenas! SMS Education on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Self-Efficacy Related to Contraception in Mozambique. Washington DC: Evidence to Action Project, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Watterson JL, Walsh J, Madeka I. Using mHealth to improve usage of antenatal care, postnatal care, and immunization: a systematic review of the literature. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:1–9. 10.1155/2015/153402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gurman TA, Rubin SE, Roess AA. Effectiveness of mHealth behavior change communication interventions in developing countries: a systematic review of the literature. J Health Commun 2012;17(Suppl1):82–104. 10.1080/10810730.2011.649160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Colaci D, Chaudhri S, Vasan A. mHealth interventions in low-income countries to address maternal health: a systematic review. Ann Glob Health 2016;82:922–35. 10.1016/j.aogh.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agarwal S, LeFevre AE, Lee J, et al. . Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist. BMJ 2016;352:i1174 10.1136/bmj.i1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. MEASURE Evaluation SIFSA. Systemic barriers to MomConnect’s capacity to reach registration targets - A process evaluation. 2016. https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tr-16-147

- 15. Barron P, Pillay Y, Fernandes A, et al. . The MomConnect mHealth initiative in South Africa: Early impact on the supply side of MCH services. J Public Health Policy 2016;37(Suppl 2):201–12. 10.1057/s41271-016-0015-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lund S, Nielsen BB, Hemed M, et al. . Mobile phones improve antenatal care attendance in Zanzibar: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:29 10.1186/1471-2393-14-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. . South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]