Abstract

Introduction

Anderson-Fabry disease (AFD) is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder caused by mutations of GLA gene leading to reduced α-galactosidase activity and resulting in a progressive accumulation of globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and its deacylated derivative, globotriaosyl-sphingosine (Lyso-Gb3). Plasma Lyso-Gb3 levels serve as a disease severity and treatment monitoring marker during enzyme replacement therapy (ERT).

Methods

Adult patients with AFD who had yearly pulmonary function tests between 1999 and 2015 were eligible for this observational study. Primary outcome measures were the change in z-score of forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and FEV1/FVC over time. Plasma Lyso-Gb3 levels and the age of ERT initiation were investigated for their association with lung function decline.

Results

Fifty-three patients (42% male, median (range) age at diagnosis of AFD 34 (6–61) years in men, 34 (13–67) in women) were included. The greatest decrease of FEV1/FVC z-scores was observed in Classic men (−0.048 per year, 95% CI −0.081 to –0.014), compared with the Later-Onset men (+0.013,95% CI −0.055 to 0.082), Classic women (−0.008, 95% CI −0.035 to +0.020) and Later-Onset women (−0.013, 95% CI −0.084 to +0.058). Cigarette smoking (P=0.022) and late ERT initiation (P=0.041) were independently associated with faster FEV1 decline. FEV1/FVC z-score decrease was significantly reduced after initiation of ERT initiation (−0.045 compared with −0.015, P=0.014). Furthermore, there was a trend towards a relevant influence of Lyso-Gb3 (P=0.098) on airflow limitation with age.

Conclusion

Early ERT initiation seems to preserve pulmonary function. Plasma Lyso-Gb3 is maybe a useful predictor for airflow limitation. Classic men need a closer monitoring of the lung function.

Keywords: rare lung diseases, copd ÀÜ mechanisms, systemic disease and lungs

Key messages.

Does early initiation of enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) and accumulation of globotriaosyl-sphingosine (Lyso-Gb3) have an effect on lung function decline in patients with Anderson-Fabry disease (AFD)?

Early initiation of ERT and smoking cessation seem to have a beneficial effect on lung function decline in AFD. Plasma Lyso-Gb3 may be used as predictor for disease severity and accelerated lung function impairment.

Pulmonologists should be aware of lung involvement in AFD since early diagnosis and treatment are potentially crucial.

Introduction

Anderson-Fabry disease (AFD) is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder caused by mutations of GLA gene leading to reduced or absent α-galactosidase A (α-gal A) enzyme activity resulting in progressive accumulation of neutral glycosphingolipids, such as globotriaosylceramide (Gb3), and its deacylated soluble derivative globotriaosylsphingosine (Lyso-Gb3) in the plasma and in tissue lysosomes.1 Eventually, ruptured lysosomes deliberate their content in the extracellular matrix triggering inflammation and subsequent fibrosis.2 Since the vascular endothelium is highly sensitive to this kind of damage, kidneys, cardiovascular system, nervous system and skin are mainly affected by the disease.3 In addition, a similar mechanism is suggested concerning the smooth muscle cells of upper and lower airways, which may further lead to obstructive sleep apnoea or bronchial/bronchiolar obstruction, respectively.4 5

Classic and Later-Onset phenotypes are known in AFD. Men with the Classic phenotype have mutations that cause an absent or very low (<1%) α-gal A activity and result in an early onset of acroparesthesias, angiokeratoma, cornea verticillata, hypohidrosis, gastrointestinal cramping and diarrhoea.6–8 With advancing age, progressive Gb3 accumulations culminate in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, renal failure, cerebrovascular disease and obstructive pulmonary disease. In contrast, men with the Later-Onset phenotype have mutations that cause a significant (>1%) residual α-gal A activity and result in cardiac, renal and cerebrovascular disease in the fourth to sixth decades of life without early clinical manifestations.8–11

Risk factors for both phenotypes are less clear and are difficult to define due to the low disease prevalence, heterogeneous disease manifestations and, in women, additionally due to a random x-chromosomal deactivation.12 13 Moreover, there is considerable uncertainty with regard to initiation of enzyme replacement therapy (ERT),14 which makes data on respiratory involvement difficult to interpret. Thus, more studies are needed to definitively underpin the association between AFD and different organ, particularly respiratory, involvement. Particularly, the effect of biomarkers, such as Gb3 and Lyso-Gb3, and the optimal timing of ERT initiation on respiratory involvement has not been investigated to date.

Residual α-gal A activity was demonstrated inversely proportional to plasma Lyso-Gb3 levels.15 Yet, Lyos-Gb3 is markedly increased in the plasma of classical Fabry patients with a higher sensitivity compared with Gb3 for the diagnosis of AFD, also in heterozygous women.16–18 Moreover, beside its use as diagnostic tool, Lyso-Gb3 seems to be a reliable therapeutic marker17 19 20 or a biomarker to predict clinical severity of the disease.21

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether Lyso-Gb3 might be a predictive biomarker for respiratory involvement of AFD as assessed by its association with pulmonary function decline alongside with other variables. Furthermore, we aimed to investigate the effect of ERT initiation on lung function decline with age.

Materials and methods

Patients

All patients in the AFD cohort at the University Hospital Zurich, which has been established in 2001 when ERT was in development, usually have at least one scheduled outpatient consultation in our centre per year. These consultations comprise an extensive clinical work-up of all possible manifestations related to AFD, such as cardiovascular system, kidneys, nervous system, eyes and lung. For purposes of the latter, there are yearly pulmonary function tests (PFTs). Based on the results of the aforementioned examinations, indications for ERT are discussed at quarterly conferences with participation of all involved disciplines. ERT was prescribed at the licensed dose of either 0.2 mg/kg body weight of recombinant agalsidase-α (Replagal) or 1 mg/kg body weight agalsidase-β (Fabrazyme) and given intravenously every 14 days. ERT was indicated in all men. In women, ERT was indicated if they had proteinuria of more than 300 mg per day, Fabry-typical kidney biopsy findings, signs of Fabry cardiomyopathy such as left ventricular hypertrophy or arrhythmia, stroke or transient ischaemic attack, acroparesthesias despite conventional analgesic therapy and/or gastrointestinal symptoms. All adult patients of this cohort who were treated and followed up at our centre from 1999 until 2015 were eligible for this retrospective observational study. Patients with at least two consecutive PFTs and known plasma Lyso-Gb3 value were included in the study. All patients had a Lyso-Gb3 measurement between October 2013 and December 2016 and had no ERT initiation or switch within at least 2 years prior to the measurement, so that the individual LysoGb3 levels were in the stable phase, as it has been shown previously.17

The study was approved by the Ethics committee of the canton of Zurich, Switzerland (KEK-ZH 2012–0115), and is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT01632111).

Pulmonary function testing

Yearly PFTs (spirometry) were performed according to performance standards based on the statements from the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society (ERS)22 at the Department of Pulmonology. The patients were asked to withhold from cigarette smoking at least 4 hours before PFT. Lung volumes were measured with a commercial ZAN300 system (nSpire Health GmbH, Oberthulba, Germany). Since z-scores are not biased by age and misdiagnosis occurs when fixed cut-offs are used,23 the lower limit of normal was defined by the fifth centile, corresponding to −1.64 z-scores according to the ERS Global Lung Function Initiative.24 Thus, as criterion to define airflow limitation, we used the ratio between the forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and the forced (expiratory) vital capacity (FVC) with a z-score cut-off of equal or below −1.64 rather than the fixed cut-off value of FEV1/FVC <70%, as recommended by others.23 25 Determination of individual z-scores was achieved with GLI-2012 Desktop Software for Individual Calculations.26

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures were the change in z-scores of FEV1 and FEV1/FVC over time. The secondary goal was to investigate factors, which may affect change in FEV1 and FEV1/FVC over time. For this purpose, age, sex, cigarette smoking, AFD phenotype (Classic vs. Later-Onset), residual α-gal activity, age at ERT initiation, Mainz Severity Score Index (MSSI) and Lyso-Gb3 were assessed. Cigarette smoking was considered positive if greater than one pack-year. MSSI is a clinical scoring system to determine the severity of Fabry disease, considering general, neurological, cardiovascular and renal abnormalities27. Cardiac involvement was defined positive if at least one cardiac MSSI variable was fulfilled. Measurement of plasma Lyso-Gb3 was performed using nano-liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry system, which was validated recently.8 18

Phenotyping

The phenotype was determined as Classic or Later-Onset based on the specific GLA mutation as reported previously.8 18 28 For novel missense mutations, the phenotype was based on clinical signs and symptoms in affected men and by in vitro expression assays.29 30

Lyso-Gb3 measurement

For serum Lyso-Gb3 levels, blood samples were centrifuged and serum was immediately frozen at −80°C for a later batch analysis. The samples were measured by high-sensitivity electrospray ionisation liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry.31 A seven-point serum calibrator and an internal standard for Lyso-Gb3 quantification (covering the analytic range from 0 to 120 ng/mL; lower limit of quantification: 0.3 ng/mL), and three level controls (3, 30 and 100 ng/mL) for quality control were used (ARCHIMED Life Science GmbH, Vienna, Austria; www.archimedlife.com). The lower limit of quantification was determined according to EP guideline 17A2 using Lyso-Gb3 calibrators 0, 0.5 and 1.0 ng/mL. The laboratory members were blinded to patient’s ID numbers, sex and all clinical and biochemical information and were not involved in the collection of samples, interpretation of data or the decision to submit this article for publication.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarised as n (%) or median (range). Variables have been included in regression models either as nominal variables or, in case of continuous data, divided into three equally sized categories. Slopes have been estimated using linear mixed models, considering age as the time variable, and including a random intercept and slope for each subject. For models comparing slopes by levels of a categorical variable x, the P value of the interaction term was used to compare the slopes, and mean estimated slopes were computed from the sum of the coefficients for age and the interactions terms with each level of x. Multivariable models have been further adjusted by inclusion of other variables that had a P value of equal or less than 0.10 in the univariable analysis. Two-sided P values were considered statistically significant if they were less than 0.05.

Statistical analysis was performed using R (R Core Team, 2013) (R V.3.4.0 (2017-04-21)), with linear mixed models estimated using the lme432 package (P values computed using the lmerTest package33). Calculation of slopes from the coefficients for the fixed effects has been performed using the multcomp34 package.

Results

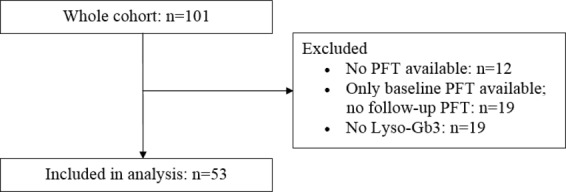

From 101 eligible patients, 53 patients (42% male) performing totally 252 PFTs were included in the study (figure 1). Baseline characteristics are shown in table 1 and the detailed demographic and biochemical information in online supplementary table 1. At baseline (diagnosis of AFD), the median age in men was 34 (range 6–61) and in women 34 (13–67) years.

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart. PFT, pulmonary function test.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics and treatment

| Baseline characteristics | Men, n=22 | Women, n=31 | P value |

| Classic phenotype | 20 (90.9%) | 27 (90.0%) | 0.45 |

| Cardiac involvement | 14 (63.6) | 11 (35.5) | 0.05 |

| Age at baseline (diagnosis of AFD), years | 34 (6–61) | 30 (13–67) | 0.99 |

| Age at ERT initiation, years | 39 (14–62) | 43 (16–68) | 0.71 |

| Time from baseline to ERT initiation, months | 12 (0–384) | 12 (0–432) | 0.72 |

| Patients on ERT | 21 (95.5) | 19 (61.3) | 0.007 |

| Patients on bronchodilators | 2 (9.1) | 1 (3.2) | 0.56 |

| Current or former cigarette smoking | 7 (31.8%) | 9 (36.0%) | 1.00 |

| MSSI, points | 16 (0–40) | 8 (0–33) | 0.01 |

| Residual α-gal activity, % | 5.5 (1.8–52.8) | 41.8 (2.2–163.0) | <0.001 |

| Lyso-Gb3, ng/mL | 40.1 (2.0–115.0) | 8.6 (0.8–23.1) | <0.001 |

| FEV1, L | 3.0 (1.8–4.1) | 2.4 (1.8–3.3) | 0.002 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 86.0 (54.0–116.0) | 87.0 (66.0–110.0) | 0.55 |

| FEV1, z-score | −2.3 (−4.4–0.7) | −1.6 (−3.1–0.2) | 0.31 |

| FEV1, z-score ≤−1.64 | 13 (56.5%) | 13 (43.3%) | 0.41 |

| FVC, L | 4.2 (2.1–5.4) | 3.0 (2.3–4.2) | <0.001 |

| FVC, % predicted | 91.0 (76.0–125.0) | 95.0 (72.0–118.0) | 0.86 |

| FVC, z-score | −1.6 (−3.6–1.1) | −1.6 (−2.7–0.7) | 0.81 |

| FVC z-score ≤−1.64 | 6 (27.3) | 9 (29.0) | 0.37 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 73 (47–88) | 78 (70–93) | 0.009 |

| FEV1/FVC, z-score | −0.9 (−5.3–1.4) | −0.6 (−2.6–1.5) | 0.12 |

| FEV1/FVC, z-score ≤−1.64 | 5 (21.7%) | 3 (10.0%) | 0.27 |

| FEF25%–27%, L | 2.2 (0.7–5.4) | 1.9 (1.0–5.2) | 0.36 |

| FEF25%–27%, % predicted | 54.0 (20.0–119.0) | 55.5 (26.0–107.0) | 0.67 |

| FEF25%–27%, z-score | −1.4 (−3.5–1.4) | −1.2 (−3.6–2.6) | 0.48 |

| FEF25%–27%, z-score ≤−1.64 | 9 (40.9) | 8 (25.8) | 0.03 |

| DLCO, % predicted | 82.0 (63.0–108.0) | 88. (61.0–115.0) | 0.44 |

Values are presented as n (%) for categorical variables (P values from Fisher’s exact test) or median (range) for continuous variables (P values from Mann-Whitney U test).

AFD, Anderson-Fabry disease; DLCO, CO diffusion capacity of the lung; ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; FEF25%–27%, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of FVC; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced (expiratory) vital capacity; MSSI, Mainz Severity Score Index; α-gal, α-galactosidase A activity.

bmjresp-2018-000277supp001.pdf (48.2KB, pdf)

In total, 40 patients were under ERT. Thirty patients received agalsidase-α and four agalsidase-β only throughout the observational period. Further six patients were switched at least once between the both ERT preparations. Thirteen patients were not on ERT: 1 man due to compliance reasons and 12 women due to lack of indication or compliance reasons.

Changes in FEV1 and FEV1/FVC over time

Median (IQR) spirometric follow-up time was 7.7 (3.7–10.1) years. When considering z-scores, 8 of 53 patients (15%) had airflow limitation (defined as FEV1/FVC (z)≤−1.64) at baseline and a total of 27 patients (51%) developed airflow limitation over time. For all patients, mean absolute FEV1 decline was −29.6 mL per year of age (95% CI −34.5 to –21.3 mL), and FEV1 z-score decreased annually by −0.01 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.06). FVC decline was −21.1 mL per year of age (95% CI −34.4 to –7.6 mL), and FVC z-score decline decreased annually by −0.007 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.01). Compared with this, FEV1/FVC z-score decreased −0.02 (95% CI −0.05 to −0.005) per year.

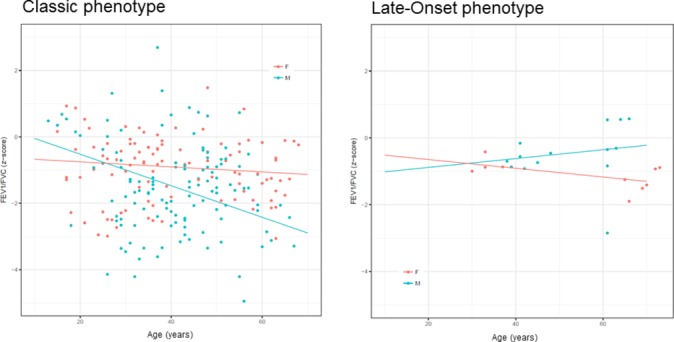

The slopes over time of FEV1/FVC in z-scores for men and women according to the phenotype are illustrated in figure 2. The greatest decrease of FEV1/FVC z-scores was observed in Classic men (−0.048 per year, 95% CI −0.081 to –0.014) compared with the Later-Onset men (+0.013, 95% CI −0.055 to 0.082), Classic women (−0.008, 95% CI −0.035 to +0.020) and Later-Onset women (−0.013, 95% CI −0.084 to +0.058).

Figure 2.

Change in FEV1/FVC (z-scores) over time. All values on y-axis are presented as z-scores from FEV1/FVC for Classic (A) and Later-Onset (B) patients, respectively, whereas age (in years) is represented by x-axis. Median (IQR) spirometric follow-up time was 7.7 (3.7–10.1) years.

Factors affecting change in FEV1 and FEV1/FVC over time

Univariate associations of slope of the two z-score outcomes with various factors are shown in table 2. Statistically significantly different slopes of FEV1 were seen by sex (P=0.048), smoking status (P=0.037), cardiac involvement by Fabry disease (P=0.033) and age at ERT initiation (P=0.029). Thus, male sex, active smoking or history of cigarette smoking, cardiac involvement and increased patient age at ERT initiation were associated with faster FEV1 decline compared with women, non-smokers, no cardiac involvement and early therapy start. Airflow limitation was significantly influenced by Lyso-Gb3 (P=0.022) and MSSI (P=0.007) with higher values associated with faster decline of FEV1/FVC.

Table 2.

Univariable analysis of estimated slopes by categorised covariates

| Variable | Levels | FEV1 (z) | P value | FEV1/FVC (z) | P value |

| Phenotype | Classic | −0.011 (−0.031, 0.008) | −0.027 (−0.048, –0.005) | ||

| Later-Onset | −0.027 (−0.082, 0.027) | 0.55 | −0.001 (−0.057, 0.055) | 0.37 | |

| Sex | Female | 0.005 (−0.020, 0.030) | −0.007 (−0.034, 0.021) | ||

| Male | −0.030 (−0.056, –0.004) | 0.048 | −0.034 (−0.065, –0.003) | 0.17 | |

| Smoking | Never smoker | 0.002 (−0.022, 0.025) | −0.022 (−0.051, 0.007) | ||

| Smoker | −0.039 (−0.070, –0.008) | 0.037 | −0.023 (−0.060, 0.014) | 0.95 | |

| Cardiac involvement | Yes | −0.043 (−0.073, –0.013) | −0.025 (−0.061, 0.011) | ||

| No | 0.001 (−0.030, 0.031) | 0.033 | −0.034 (−0.070, 0.002) | 0.72 | |

| Lyso-Gb3, ng/mL | <8.6 | 0.012 (−0.030, 0.053) | 0.59 | −0.012 (−0.050, 0.026) | 0.5 |

| 8.6–21.2 | −0.001 (−0.034, 0.032) | 0.004 (−0.029, 0.037) | |||

| ≥21.3 | −0.032 (−0.064, 0.000) | 0.14 | −0.048 (−0.082, –0.013) | 0.022 | |

| α-Gal activity, % | <9 | −0.040 (−0.084, 0.004) | 0.096 | −0.034 (−0.082, 0.014) | 0.36 |

| Sep-40 | 0.013 (−0.036, 0.062) | −0.003 (−0.052, 0.047) | |||

| ≥41 | 0.007 (−0.045, 0.059) | 0.85 | 0.010 (−0.041, 0.060) | 0.75 | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | <25 | −0.007 (−0.054, 0.040) | 0.07 | −0.091 (−0.150, –0.033) | 0.13 |

| 25–41 | −0.056 (−0.096, 0.016) | −0.053 (−0.101, –0.004) | |||

| ≥42 | −0.039 (−0.081, 0.002) | 0.5 | −0.033 (−0.081, 0.016) | 0.5 | |

| MSSI, points | <6 | −0.009 (−0.053, 0.035) | 0.67 | −0.024 (−0.069, 0.021) | 0.15 |

| 6–15.6 | 0.002 (−0.035, 0.040) | 0.016 (−0.023, 0.055) | |||

| ≥15.7 | −0.018 (−0.051, 0.014) | 0.35 | −0.050 (−0.084, –0.016) | 0.007 | |

| Age at ERT initiation, years | <35 | 0.004 (−0.046, 0.054) | 0.029 | −0.061 (−0.128, 0.005) | 0.95 |

| 35–45 | −0.059 (−0.098, –0.019) | −0.064 (−0.117, –0.011) | |||

| ≥46 | −0.037 (−0.079, 0.006) | 0.38 | −0.007 (−0.063, 0.049) | 0.093 |

Values are estimated slopes of z-values (95% CI) and P values, respectively. For covariates with three categories, the ranges for each category are lowest, mid (highest minus lowest), highest. Median (IQR) spirometric follow-up time was 7.7 (3.7, 10.1) years.

α-Gal, α-galactosidase A enzyme; ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; MSSI, Mainz Severity Score Index.

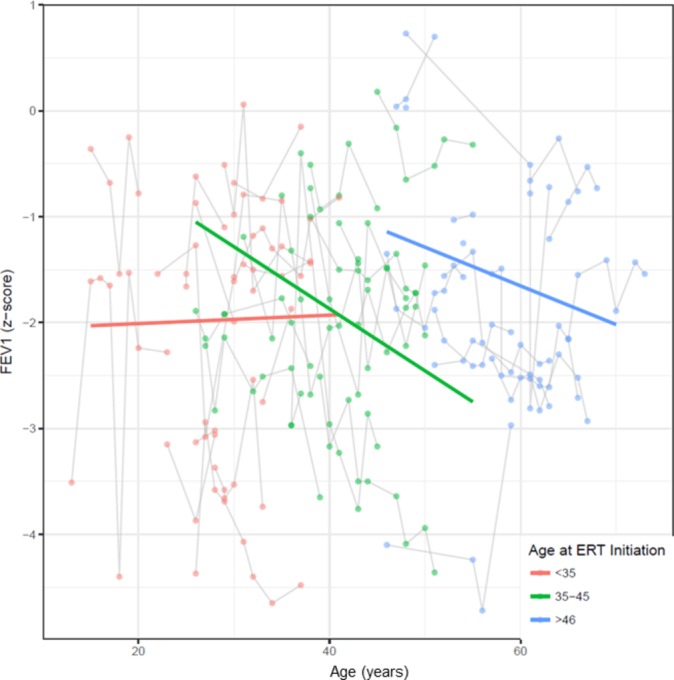

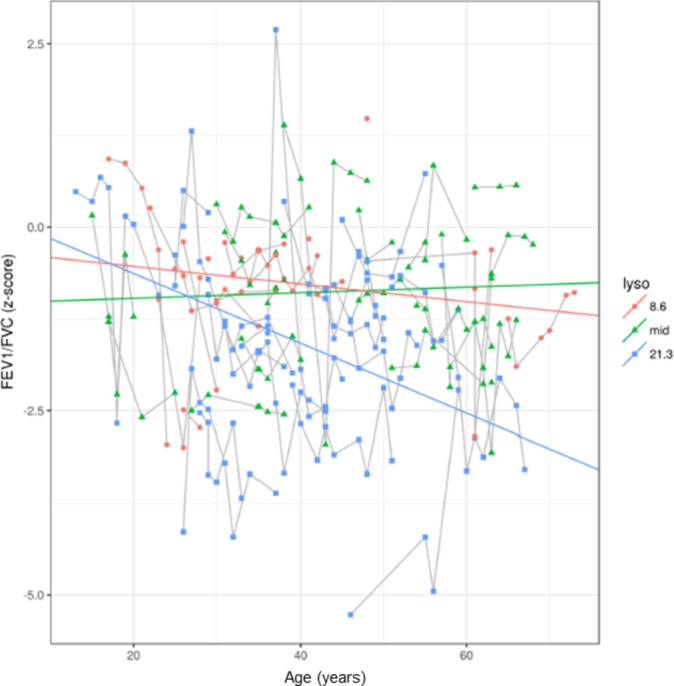

Table 3 shows the results from the multivariable models, adjusting for other factors (sex, smoking, Lyso-Gb3, MSSI and age at ERT initiation). The only significant interactions with age after adjustment were history of cigarette smoking (P=0.022) and age at ERT initiation (P=0.041) with FEV1 (figure 3). Thus, current or former smokers and those with delayed ERT initiation had significantly faster FEV1 decline. There was no significant association of the investigated variables with airflow limitation over time. However, there was a considerable trend towards a clinically relevant influence of Lyso-Gb3 (P=0.098) on airflow limitation with age (figure 4). Considering a model where the change in pulmonary function parameters over time varying by ERT status, there was a statistical significant interaction for the FEV1/FVC z-score with an improved slope (−0.045 compared with −0.015, P=0.014) after initiation of ERT (table 4).

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of estimated slopes by categorised covariates

| Variable | Levels | FEV1 (z) | P value | FEV1/FVC (z) | P value |

| Sex | Female | −0.025 (−0.062, 0.013) | −0.044 (−0.089, 0.001) | ||

| Male | −0.052 (−0.082, –0.022) | 0.19 | −0.070 (−0.106, –0.028) | 0.26 | |

| Smoking | Never smoker | −0.025 (−0.055, 0.005) | −0.059 (−0.099, –0.020) | ||

| Smoker | −0.073 (−0.109, –0.037) | 0.022 | −0.063 (−0107, –0.019) | 0.86 | |

| Lyso-Gb3, nmol/L | <8.6 | −0.020 (−0.078, 0.038) | 0.65 | −0.042 (−0.101, 0.017) | 0.54 |

| 8.6–21.2 | −0.034 (−0.079, 0.011) | −0.027 (−0.077, 0.024) | |||

| ≥21.3 | −0.049 (−0.085, –0.011) | 0.52 | −0.073 (−0.116, –0.030) | 0.098 | |

| MSSI, points | <6 | −0.044 (−0.096, 0.008) | 0.79 | −0.067 (−0.126, –0.010) | 0.15 |

| 6–15.6 | −0.037 (−0.083, 0.008) | −0.021 (−0.075, 0.032) | |||

| ≥15.7 | −0.042 (−0.079, –0.006) | 0.73 | −0.069 (−0.113, –0.026) | 0.053 | |

| Age at ERT initiation, years | <35 | −0.013 (−0.063, 0.037) | 0.041 | −0.091 (−0.154, 0.028) | 0.17 |

| 35–45 | −0.056 (−0.107, –0.005) | −0.037 (−0.101, –0.028) | |||

| ≥46 | −0.031 (−0.078, 0.016) | 0.42 | −0.004 (−0.054, 0.062) | 0.28 |

Values are estimated slopes (95% CI) and P values, respectively. For covariates with three categories, the ranges for each category are lowest, mid (highest minus lowest), highest. Median (IQR) spirometric follow-up time was 7.7 (3.7, 10.1) years.

ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; MSSI, Mainz Severity Score Index.

Figure 3.

Slope of FEV1 by age at enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) initiation FEV1 z-score slope (y-axis) by age categorised in three groups (red, ERT initiation <35 years; green, ERT initiation between 35 and 45 years; blue, ERT initiation above 46 years). ERT initiation <35 years resulted in improvement of FEV1 over time compared with later initiation. Median (IQR) spirometric follow-up time was 7.7 (3.7, 10.1) years.

Figure 4.

Slope of FEV1/FVC by Lyso-Gb3 category FEV1/FVC z-score (y-axis) by age (x-axis) categorised by three categories according to Lyso-Gb3 levels (red, lowest Lyso-Gb3 level of 8.6 ng/mL; green, mid level of Lyso-Gb3; blue, highest Lyso-Gb3 level of 21.3 ng/mL). Patients with highest Lyso-Gb3 levels had faster FEV1/FVC z-score decline compared with those with lower levels. Median (IQR) spirometric follow-up time was 7.7 (3.7, 10.1) years.

Table 4.

Annual pulmonary function changes before and after initiation of enzyme replacement therapy

| Before initiation of ERT | After initiation of ERT | P value | |

| FEV1, mL | −32.4 (−43.5, –21.4) | −26.3 (39.7, –13.0) | 0.12 |

| FEV1, z-score | −0.010 (−0.029, 0.009) | −0.010 (−0.036, 0.015) | 0.99 |

| FVC, mL | −14.7 (−29.3, –10.0) | −14.3 (−30.8, 2.1) | 0.11 |

| FVC, z-scores | 0.157 (−0.155, 0.470) | 0.077 (−0.182, 0.337) | 0.42 |

| FEV1/FVC, z-score | −0.045 (−0.075, –0.014) | −0.015 (−0.036, 0.006) | 0.014 |

| FEF25%–75%, mL | −45.1 (−64.7, –25.5) | −43.3 (−56.5, –30.1) | 0.81 |

| FEF25%–75%, z-score | −0.004 (−0.030, 0.022) | 0.002 (−0.014, 0.018) | 0.56 |

| DLCO, % predicted | 0.07 (−0.32, 0.47) | −0.09 (−0.36, 0.17) | 0.34 |

Values are estimated slopes (95% CI) of annual pulmonary function change, whereas median (IQR) spirometric follow-up time was 7.7 (3.7, 10.1) years.

DLCO, CO diffusion capacity of the lung; ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; FEF25%–75%, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of FVC; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced (expiratory) vital capacity.

Discussion

There is increasing evidence of a functionally relevant pulmonary involvement of AFD, which is clinically apparent as airflow limitation early in lifetime of these patients compared with non-Fabry diseased populations.5 35–37 The pathological mechanism of this disorder is most likely due to lysosomal accumulation of neutral glycosphingolipids in bronchial mucosa and smooth-muscle cells that result in small and medium airway narrowing.35 38–44 However, due to limited sample sizes of the available studies on this orphan disease and due to heterogeneous phenotypes of AFD and uncertainty with regard to adequate timing of ERT initiation, patients at increased risk of pulmonary involvement are difficult to define.12 Notably, neither MSSI nor residual α-gal activity was associated with FEV1 decline or the appearance of airflow limitation in the latter study.

In the present considerably large single-centre cohort study on patients of both sexes with AFD, we have addressed this gap by investigating plasma Lyso-Gb3 and age at ERT initiation in addition to conventional factors that have been described in a recent publication by our group.12 Plasma Lyso-Gb3 has been demonstrated to be a reliable therapeutic marker17 20 45 as well as biomarker to predict clinical severity of AFD.21 Thus, we hypothesised that plasma Lyso-Gb3 in patients with AFD might correlate with lung function decline, particularly the appearance of airflow limitation.

We found that increased plasma Lyso-Gb3 levels show an independent trend towards a clinically relevant risk of airflow limitation with age. Thus, plasma Lyso-Gb3 is likely to be a useful predictor of pulmonary involvement in terms of early airflow limitation and might help for risk stratification and treatment decisions. Notably, there was no other factor associated with airflow limitation over time, yet Lyso-Gb3 might have become significant with a higher number of included subjects. Noteworthy, the suggested relationship between Lyso-Gb3 and airflow limitation underlines the existence of pulmonary involvement by AFD.

Importantly, pulmonary involvement seems to be more prominent in Classic than in Later-Onset men and the women of both phenotypes. This finding suggests that the residual α-gal A activity in women and Later-Onset phenotype individuals is sufficient to clear the bronchial mucosa and smooth-muscle cells from the Gb3 depositions, this in analogy to the vascular endothelial cells.1

Attempts to predict the lung phenotype based on the type or location of the GLA mutation have already been undertaken by the group of Brown et al.35 In this study, three patients with frameshift mutations and two with the missense mutation D264V, which markedly alters the enzymatic α-gal A structure and function, exhibited airway obstruction, consistent with the absence of enzymatic activity. In contrast, the patients with other, less severe missense mutations did not. The authors stated that drawing conclusions may be somewhat premature because their studies were limited by the small number of patients. Our much larger study confirms this previous assumption and our results suggest that closer systematic monitoring of Classic men for pulmonary disease might be helpful in diagnosing and early treatment of Fabry pneumopathy.

Concerning FEV1 slopes, we found that cigarette smoking and later ERT initiation were associated with faster FEV1 decline. The latter finding brings new light into an area of uncertainty. There are limited data on the effect of ERT on pulmonary involvement of AFD,40 44 46 47 and the optimal time for initiation of ERT is unknown.35 Several case reports and small case series stated that ERT has beneficial effects on PFT by stabilising or even increasing FVC and/or FEV1.40 44 46 Our data suggest that an earlier ERT initiation probably helps to stabilise FEV1 decline and preserve pulmonary function. Similarly, Arends et al found in their retrospective cohort that ERT initiation before the age of 25 years resulted in lower Lyso-Gb3 levels after 1 year compared with those with a later treatment start.20 Thus, early ERT initiation seems to result in better biochemical response and, subsequently, slower FEV1 decline. Furthermore, we were able to show a significantly improved annual decrease of FEV1/FVC z-score after initiation of ERT compared with before the onset of treatment, which is a unique finding in the literature.

The possible association between cigarette smoking and FEV1 decline in patients with AFD is not new and confirms the findings of others.35 48 However, a very recent study by our group found no significant association between cigarette smoking and FEV1 decline.12

Since this is the first study to show a probable association between plasma Lyso-Gb3 and airflow limitation, and an independent association between age at ERT initiation and FEV1 decline, respectively, these findings must be confirmed in a larger cohort. However, our study has included a considerably large sample size of patients with AFD. Moreover, we are able to overcome the drawback of earlier studies on pulmonary function in patients with AFD5 because we now used z-scores, which are not biased by age, rather than the fixed cut-off ratio of FEV1/FVC <70%. The latter value generally leads to an underestimation of the prevalence of airflow limitation in younger individuals.23 25

There are some limitations of our study that have to be mentioned. First, the retrospective study design is a possible source of bias. However, a prospective investigation of the optimal time of ERT initiation is likely impossible due to ethical concerns. On the other hand, we did not compare treated and untreated patients since the latter group include mainly asymptomatic women. Second, Lyso-Gb3 values are subject to changes during ERT,17 45 which might have an effect on its applicability. The association of lysoGb3 and airflow limitation would possibly become significant, when only pre-ERT values were used for statistical analysis. A further limitation is that the number of Later-Onset patients is low in our cohort; therefore, our results need to be confirmed by studies with more Later-Onset patients. Lastly, since we normally do not perform body plethysmographies in Fabry patients, and since respiratory symptoms such as chronic cough and sputum production were not systematically captured, a clear differentiation from COPD is not possible, thus an overlap between Fabry-associated lung disease and COPD cannot not be excluded.

Conclusion

This is the first study to show a probable association in patients with AFD between plasma Lyso-Gb3 and airflow limitation on one hand, and an independent association between age at ERT initiation and FEV1 decline on the other hand. Thus, plasma Lyso-Gb3 could be useful as clinical predictor of pulmonary involvement by AFD, alongside conventional risk factors such as cigarette smoking, male gender and age. Furthermore, our data suggest earlier ERT initiation since this may help to stabilise FEV1 decline and preserve pulmonary function. In addition, this is the first study demonstrating a significantly improved annual decline of FEV1/FVC z-score after initiation of ERT. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception: DF, PAK, AN. Data collection: DF, AN. Data analysis and interpretation: DF, SRH, DCK, TPM, AJF, AN. Drafting of the article: DF, SRH, AN. Critical revision: PAK, DCK, TPM, AJF. Final approval: all authors.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: AN is a consultant to Shire, received lecturing honoraria and research support from Sanofi Genzyme and Shire, and received financial publication support of this paper from Sanofi Genzyme.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: KEK-ZH 2012-0115.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data can be requested from the first or last author by email.

References

- 1. Desnick R, Ioannou Y, Eng C, et al. α-Galactosidase a deficiency: Fabry disease : Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001:3733–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Francesco PN, Mucci JM, Ceci R, et al. Fabry disease peripheral blood immune cells release inflammatory cytokines: role of globotriaosylceramide. Mol Genet Metab 2013;109:93–9. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zarate YA, Hopkin RJ. Fabry’s disease. Lancet 2008;372:1427–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61589-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Franzen D, Gerard N, Bratton DJ, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of sleep disordered breathing in Fabry disease: a prospective cohort study. Medicine 2015;94:e2413 doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Franzen D, Krayenbuehl PA, Lidove O, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Fabry disease: overview and perspectives. Eur J Intern Med 2013;24:707–13. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. MacDermot KD, Holmes A, Miners AH. Anderson-Fabry disease: clinical manifestations and impact of disease in a cohort of 60 obligate carrier females. J Med Genet 2001;38:769–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schiffmann R, Warnock DG, Banikazemi M, et al. Fabry disease: progression of nephropathy, and prevalence of cardiac and cerebrovascular events before enzyme replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:2102–11. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfp031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nowak A, Mechtler TP, Hornemann T, et al. Genotype, phenotype and disease severity reflected by serum LysoGb3 levels in patients with Fabry disease. Mol Genet Metab 2018;123 doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. von Scheidt W, Eng CM, Fitzmaurice TF, et al. An atypical variant of Fabry’s disease with manifestations confined to the myocardium. N Engl J Med 1991;324:395–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199102073240607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakao S, Kodama C, Takenaka T, et al. Fabry disease: detection of undiagnosed hemodialysis patients and identification of a "renal variant" phenotype. Kidney Int 2003;64:801–7. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shabbeer J, Yasuda M, Benson SD, et al. Fabry disease: identification of 50 novel alpha-galactosidase A mutations causing the classic phenotype and three-dimensional structural analysis of 29 missense mutations. Hum Genomics 2006;2:297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Franzen DP, Nowak A, Haile SR, et al. Long-term follow-up of pulmonary function in Fabry disease: a bi-center observational study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180437 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Echevarria L, Benistan K, Toussaint A, et al. X-chromosome inactivation in female patients with Fabry disease. Clin Genet 2016;89 doi:10.1111/cge.12613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schiffmann R, Hughes DA, Linthorst GE, et al. Screening, diagnosis, and management of patients with Fabry disease: conclusions from a "Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes" (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2017;91:284–93. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vedder AC, Breunig F, Donker-Koopman WE, et al. Treatment of Fabry disease with different dosing regimens of agalsidase: effects on antibody formation and GL-3. Mol Genet Metab 2008;94:319–25. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aerts JM, Groener JE, Kuiper S, et al. Elevated globotriaosylsphingosine is a hallmark of Fabry disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:2812–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0712309105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Breemen MJ, Rombach SM, Dekker N, et al. Reduction of elevated plasma globotriaosylsphingosine in patients with classic Fabry disease following enzyme replacement therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1812:70–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nowak A, Mechtler TP, Desnick RJ, et al. Plasma LysoGb3: a useful biomarker for the diagnosis and treatment of Fabry disease heterozygotes. Mol Genet Metab 2017;120:57–61. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Togawa T, Kodama T, Suzuki T, et al. Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine as a biomarker of Fabry disease. Mol Genet Metab 2010;100:257–61. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arends M, Wijburg FA, Wanner C, et al. Favourable effect of early versus late start of enzyme replacement therapy on plasma globotriaosylsphingosine levels in men with classical Fabry disease. Mol Genet Metab 2017;121:157–61. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krüger R, Tholey A, Jakoby T, et al. Quantification of the Fabry marker lysoGb3 in human plasma by tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2012;883-884:128–35. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38. doi:10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stanojevic S, Wade A, Stocks J. Reference values for lung function: past, present and future. Eur Respir J 2010;36:12–19. doi:10.1183/09031936.00143209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1324–43. doi:10.1183/09031936.00080312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hansen JE, Sun XG, Wasserman K. Spirometric criteria for airway obstruction: use percentage of FEV1/FVC ratio below the fifth percentile, not < 70%. Chest 2007;131:349–55. doi:10.1378/chest.06-1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Society ER. GLI calculator, Excel Sheet Calculator. Secondary GLI calculator, Excel Sheet Calculator. 2014. http://www.ers-education.org/guidelines/global-lung-function-initiative/tools/excel-sheet-calculator.aspx.

- 27. Whybra C, Kampmann C, Krummenauer F, et al. The Mainz Severity Score Index: a new instrument for quantifying the Anderson-Fabry disease phenotype, and the response of patients to enzyme replacement therapy. Clin Genet 2004;65:299–307. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00219.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nowak A, Koch G, Huynh-Do U, et al. Disease progression modeling to evaluate the effects of enzyme replacement therapy on kidney function in adult patients with the classic phenotype of Fabry disease. Kidney Blood Press Res 2017;42:1–15. doi:10.1159/000464312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spada M, Pagliardini S, Yasuda M, et al. High incidence of later-onset Fabry disease revealed by newborn screening. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:31–40. doi:10.1086/504601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yasuda M, Shabbeer J, Benson SD, et al. Fabry disease: characterization of alpha-galactosidase A double mutations and the D313Y plasma enzyme pseudodeficiency allele. Hum Mutat 2003;22:486–92. doi:10.1002/humu.10275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gold H, Mirzaian M, Dekker N, et al. Quantification of globotriaosylsphingosine in plasma and urine of Fabry patients by stable isotope ultraperformance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem 2013;59:547–56. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2012.192138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, et al. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 2015;67:1–48. doi:10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kuznetsova ABB, Haubo Bojesen Christensen R. ImerTest: tests in linear mixed effects models. R package version 2.0-33, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J 2008;50:346–63. doi:10.1002/bimj.200810425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brown LK, Miller A, Bhuptani A, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Fabry disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:1004–10. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9116979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tran C, Barbey F, Lazor R, et al. Pulmonary involvement in adult patients with inborn errors of metabolism. Respiration 2017;94:2–13. doi:10.1159/000475762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Faverio P, Mantero M, Pieruzzi F, et al. Early recognition of airway obstruction in Fabry disease and correlation with dyspnea: a case series. Minerva Pneumol 2016;55:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith P, Heath D, Rodgers B, et al. Pulmonary vasculature in Fabry’s disease. Histopathology 1991;19:567–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosenberg DM, Ferrans VJ, Fulmer JD, et al. Chronic airflow obstruction in Fabry’s disease. Am J Med 1980;68:898–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang RY, Abe JT, Cohen AH, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy stabilizes obstructive pulmonary Fabry disease associated with respiratory globotriaosylceramide storage. J Inherit Metab Dis 2008;31(Suppl 2):S369–74. doi:10.1007/s10545-008-0930-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kelly MM, Leigh R, McKenzie R, et al. Induced sputum examination: diagnosis of pulmonary involvement in Fabry’s disease. Thorax 2000;55:720–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bierer G, Kamangar N, Balfe D, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in Fabry disease. Respiration 2005;72:504–11. doi:10.1159/000087675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Magage S, Lubanda JC, Susa Z, et al. Natural history of the respiratory involvement in Anderson-Fabry disease. J Inherit Metab Dis 2007;30:790–9. doi:10.1007/s10545-007-0616-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Odler B, Cseh Á, Constantin T, et al. Long time enzyme replacement therapy stabilizes obstructive lung disease and alters peripheral immune cell subsets in Fabry patients. Clin Respir J 2017;11:942–50. doi:10.1111/crj.12446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Togawa T, Kawashima I, Kodama T, et al. Tissue and plasma globotriaosylsphingosine could be a biomarker for assessing enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;399:716–20. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim W, Pyeritz RE, Bernhardt BA, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of Fabry disease and positive response to enzyme replacement therapy. Am J Med Genet A 2007;143:377–81. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barbey F, Widmer U, Brack T, et al. Spirometric abnormalities in patients with Fabry disease and effect of enzyme replacement therapy. Acta Paediatr 2005;447(Suppl):105. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aubert JD, Barbey F. Pulmonary involvement in Fabry disease : Mehta A, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G, Fabry disease: perspectives from 5 years of FOS. Oxford: Oxford PharmaGenesis, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjresp-2018-000277supp001.pdf (48.2KB, pdf)