Abstract

This systematic review aims to estimate the prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by physicians in the UK. Five databases were searched for surveys monitoring the prevalence of use of CAM, which were published between 1 January 1995 and 7 December 2011. In total, 14 papers that reported 13 separate surveys met our inclusion criteria. Most were of poor methodological quality. The average prevalence of use of CAM across all surveys was 20.6% (range 12.1–32%). The average referral rate to CAM was 39% (range 24.6–86%), and CAM was recommended by 46% of physicians (range 38–55%). The average percentage of physicians who had received training in CAM was 10.3% (range 4.8–21%). The three most commonly used methods of CAM were acupuncture, homeopathy and relaxation therapy. A sizable proportion of physicians in the UK seem to employ some type of CAM, yet many have not received any training in CAM. This raises issues related to medical ethics, professional competence and education of physicians.

Key Words: complementary and alternative medicine, survey, systematic review

Introduction

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been defined as ‘diagnosis, treatment and/or prevention which complements mainstream medicine by contributing to a common whole, satisfying a demand not met by orthodoxy, or diversifying the conceptual framework of medicine’.1 The prevalence of use of CAM by physicians in the UK has been reported to be high, yet few doctors have sufficient training in this area.2 Different surveys have generated vastly different prevalence rates; the true level of use of CAM by physicians in the UK is therefore less than clear. This systematic review aimed to summarise and critically evaluate surveys monitoring the prevalence of use of CAM by physicians in the UK during the last 15 years.

Methods

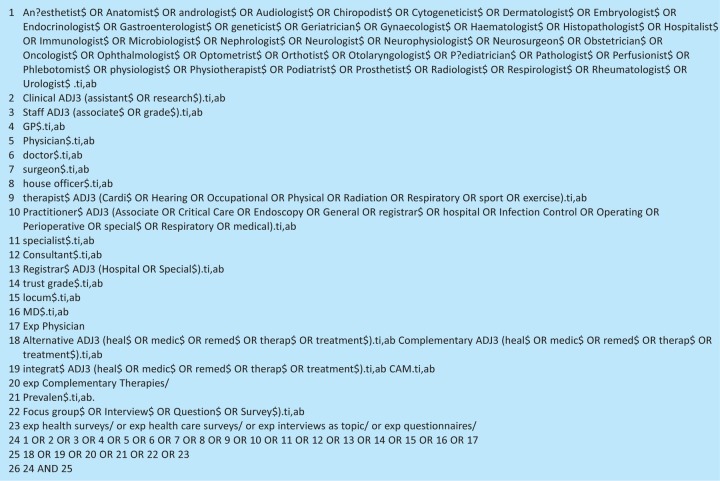

Systematic literature searches were performed for all English language references using AMED, CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase and Medline for surveys published between 1 January 1995 and 7 December 2011 (a previous review evaluated earlier surveys).3 Details of the search strategy are summarised in the appendix. In addition, relevant book chapters, review articles and our own departmental files were searched by hand for further relevant articles.

Only surveys that reported quantitative data on prevalence of use of CAM by physicians in the UK were included. Surveys that reported only qualitative data were excluded. Information from the included surveys was extracted according to predefined criteria and assessed by two independent reviewers. Any disagreements were settled through discussion.

The following methods were considered as CAM: acupuncture/acupressure, Alexander technique, aromatherapy, autogenic training, Ayurveda, (Bach) flower remedies, biofeedback, chelation therapy, chiropractic, Feldenkrais, herbal medicine, homeopathy, hypnotherapy, imagery, kinesiology, massage of any form, meditation, naturopathy, neural therapy, osteopathy, qi gong, reflexology, relaxation therapy, shiatsu, spiritual healing, static magnets, tai chi and yoga. Non-herbal dietary supplements and vitamins, psychotherapy, physical exercises and some physiotherapeutic modalities such as electrotherapy and ultrasound were not considered to be CAM and therefore were excluded from our analyses.

Use of CAM was defined as the provision of any type of access to CAM, including recommendations, referrals, provision of treatment or self-administration. Where available, we calculated the average of the percentage of responders who stated that they recommended, referred or practised CAM.

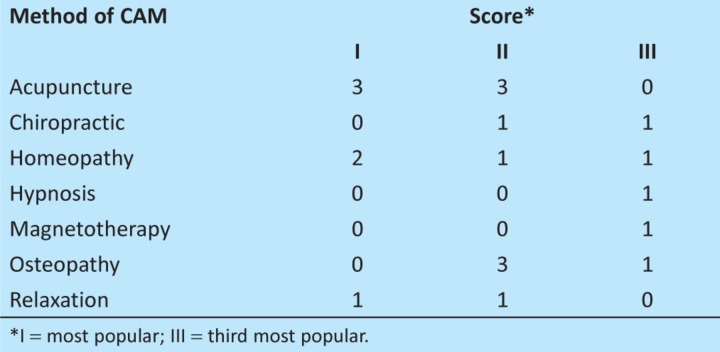

In studies in which percentage values for more than two methods of CAM were provided, we ranked the top three methods of CAM from each survey (I = most popular) and then averaged the rank numbers across the surveys to generate an overall ranking. We also provided the total number of surveys in which a particular method of CAM was the most prevalent/popular and then calculated the averages of those figures. Where available, we calculated the average of the percentage of responders who stated that they experienced benefit or were satisfied with CAM, as well as those who reported adverse effects (AEs) after using CAM and the cost of purchasing CAM.

Surveys were further classified according to the following criteria: sample size, response rate and random sampling. We also created a category of ‘high-quality surveys’, which had to have a sample size >1,000 and a response rate >70% and had to employ a random-sampling technique.

Results

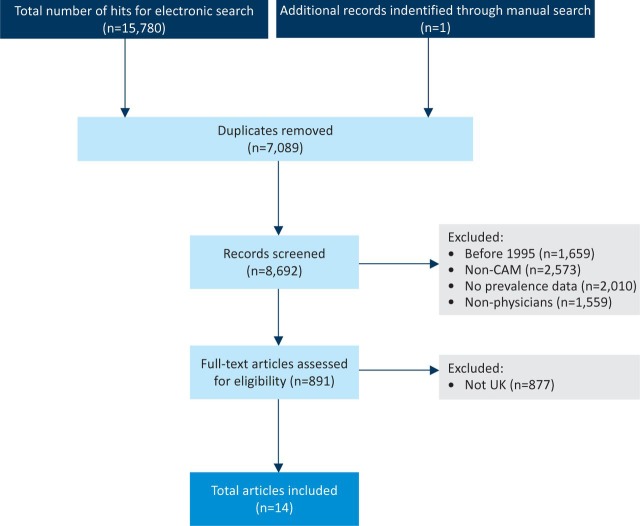

The searches generated 15,781 potentially relevant titles and abstracts, of which 15,767 were excluded (Fig 1). This resulted in a total of 14 articles, which reported 13 separate surveys.2,4–16 Detailed characteristics of the included surveys are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Eight surveys originated from England, three from Scotland and three from the whole of the UK.

Fig 1.

Study flow diagram.

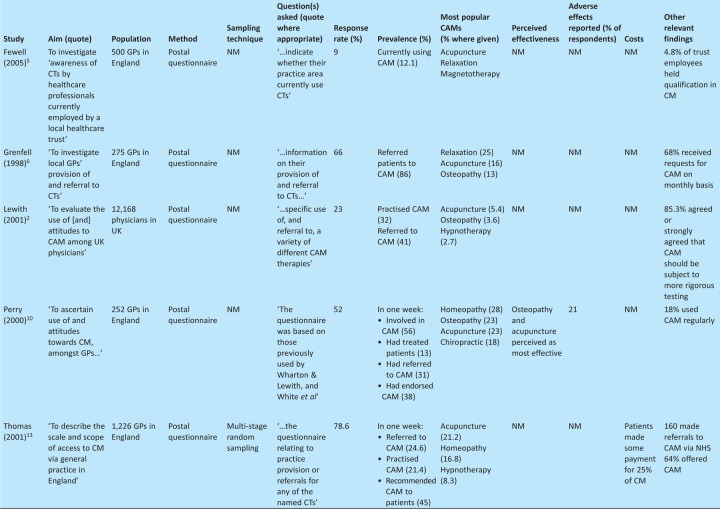

Table 1.

Prevalence of the use of or referrals to CAM by physicians in UK since 1995.

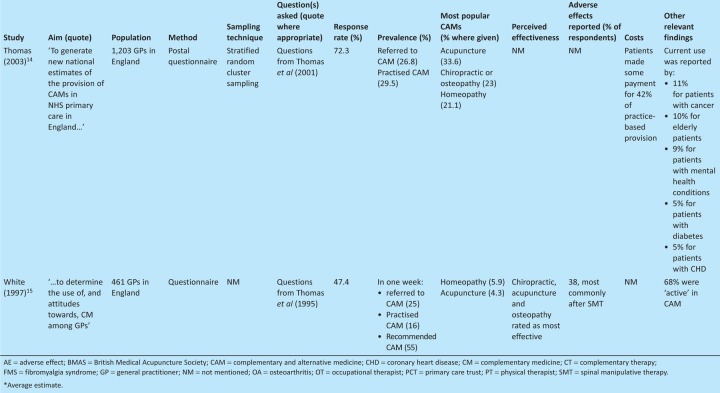

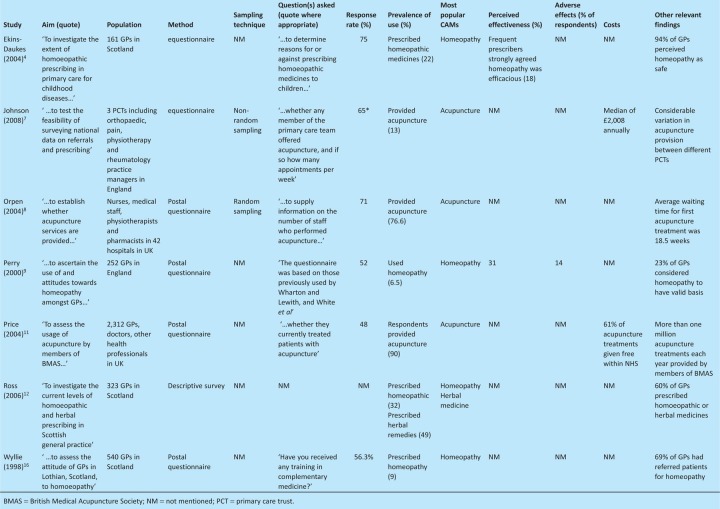

Table 2.

Prevalence of use of specific methods of CAM by physicians in UK since 1995.

Seven surveys investigated the use of CAM in general terms (see Table 1).2,5,6,10,13–15 Across these surveys, the average prevalence of use of CAM (within the past week) was 20.6% (range 12.1–32%). The average prevalence of referrals to CAM was 39% (range 24.6–86%). On average, CAM was recommended by 46% (range 38–55%) of physicians. The average percentage of physicians who had received any training in CAM was 10.3% (range 4.8–21%).

In surveys with a response rate >50%, the average prevalence of use of CAM was 21.3% (range 13–29.5%). In surveys with a response rate <50%, the average prevalence of use of CAM was 20% (range 12.1–32%). Two surveys13,14 met all of the above criteria for methodological quality. They reported an average prevalence of 25.4% (range 21.4–29.5%).

Seven surveys assessed the use of two specific methods of CAM: homeopathy4,9,12,16 and acupuncture7,8,11 (see Table 2). The average prevalence for physicians’ use was 21.6% (range 6.5–49%) for homeopathy and 59.8% (range 13–90%) for acupuncture.

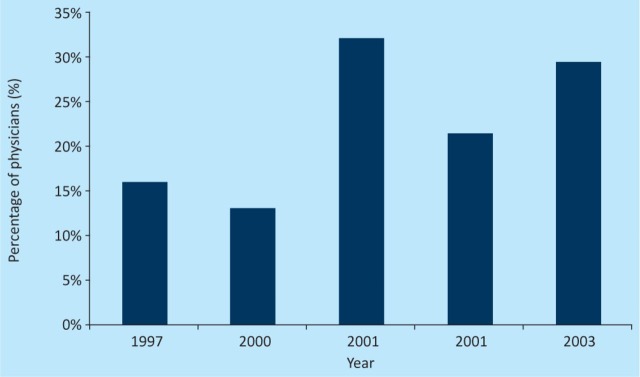

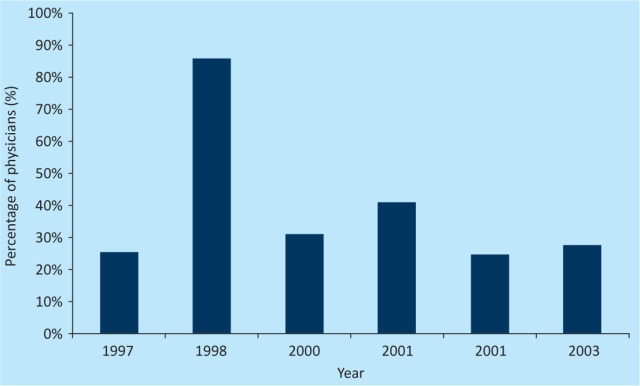

Figures 2 and 3 estimate changes over time. From Fig 2, one might assume that the prevalence of use of CAM in 2001 and 2003 was higher than in 1997 and 2000: the average physicians’ use of CAM in 1997 and 2000 was 14.5% (range 13–16%); this percentage was 27.6% (range 21.4–32) in 2001 and 2003. Fig 3 fails to indicate any clear changes in referral rates between 1997 and 2003.

Fig 2.

Changes over time in physicians’ use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) (only surveys of use of CAM in general).

Fig 3.

Changes over time in physicians’ referral to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) (only surveys of use of CAM in general).

The methodological quality of most surveys was poor. Frequent weaknesses included no mention of sampling technique, small sample size, low response rate and lack of validated outcome measures. The use of a random-sampling method was mentioned in three (23%) surveys.8,13,14 The response rates ranged between 9% and 78.6% (average 55.3%).

Perceived effectiveness of CAM was mentioned in three (23%) surveys.4,9,10,15 The average perceived effectiveness for these three surveys was 24.5% (range 18–31%). The percentage of physicians who reported AEs was mentioned in two (15.3%) surveys,9,10,15 for which the average was 24.3% (range 14–38%). The costs of CAM were given in four (30.7%) surveys.7,11,13,14 Based on one survey, the median annual cost of acupuncture was £2,008 per eight acupuncture GP practices.7

Acupuncture was the most popular type of CAM in three surveys (second most popular in three surveys; third in no surveys), homeopathy was the most popular in two studies (second in one survey; third in three surveys) and relaxation techniques were most popular in one survey (second in one survey; third in no surveys) (Table 3). Using our ranking method, acupuncture was the most popular form of CAM (23% of surveys), followed by homeopathy (15.3%) and relaxation techniques (7.6%).

Table 3.

Ranking scores.

Discussion

Our review suggests that physicians in the UK make ample use of CAM. There are, however, many caveats. Most surveys were of poor quality and their findings are thus less than reliable. The methods employed varied considerably and so comparisons between surveys and trends over time must be interpreted cautiously. It is obvious that the results of such surveys will depend on the population targeted. If, for instance, members of an acupuncture organisation are surveyed, it is hardly surprising to find that 90% of them use acupuncture.11 Similarly, it might be suspected that physicians with an interest in CAM tend to reply to such surveys, while others do not. This, in turn, would result in erroneously high prevalence rates, particularly in surveys with low response rates.

The relatively high percentage of physicians who reported AEs is of concern. For example, in the survey of White et al (1997), 38% of physicians reported AEs, mostly after spinal manipulation therapy (SMT).15 As several hundred severe complications have been reported after upper spinal manipulations and the effectiveness of SMT is not well documented (for example references 17 and 18) many authors have questioned whether this therapy generates more good than harm.19,20

As many doctors in the UK seem to use or recommend CAM, one ought to ask whether this is ethical. Doctors have a duty of care that essentially means they should treat each patient with the optimal treatment for his or her condition. As the evidence for most forms of CAM is far from strong,21 the use of CAM in routine healthcare may present an ethical problem. It has been argued that the use of homeopathy, a form of CAM that is biologically implausible22 and for which clinical evidence is weak,23 conflicts with medical ethics.24,25 Similarly, one ought to investigate why only 10.3% of doctors claim to have training in CAM yet many more seem to use CAM, as our analyses reveal. This discrepancy seems to indicate that there is an urgent need to educate doctors about the essential facts related to this area.26 In turn, this should be seen in the context of the current debate about the scientific rigor of courses in CAM for healthcare professionals.27

Our review has several limitations. Even though our searches were extensive, we cannot be entirely sure that all relevant articles containing prevalence rates were located. Secondly, there is no gold-standard assessment tool for surveys,28 so a formal quality assessment was deemed implausible. In addition, the results of our analyses should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. First and foremost, calculating average percentage values may promote a positive or negative skew as surveys were based on various sample sizes. Secondly, in eight surveys4,5,7–9,11,12,16 the percentage values of the most popular CAM modalities were not provided. This means that our top three ranking list is based on six surveys. Thirdly, six surveys4,7–9,11,16 investigated the use of single methods of CAM, namely homeopathy and acupuncture, and did not include other CAMs.

In conclusion, most surveys that have monitored physicians’ use of CAM in the UK are less than rigorous. The current evidence suggests that the prevalence is high, which raises ethical and competence issues. The most popular treatments are acupuncture, homeopathy and relaxation techniques.

Appendix 1.

Detailed search strategy for Medline.

References

- 1.Ernst E. Pittler MH. Wider B. Boddy K. The desktop guide to complementary and alternative medicine. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Elsevier Mosby; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewith GT. Hyland M. Gray SF. Attitudes to and use of complementary medicine among physicians in the United Kingdom. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9:167–72. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2001.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ernst E. Resch KL. White AR. Complementary medicine. What physicians think of it: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:2405–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.155.22.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekins-Daukes S. Helms PJ. Taylor MW, et al. Paediatric homoeopathy in general practice: where, when and why? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:743–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fewell F. Mackrodt K. Awareness and practice of complementary therapies in hospital and community settings within Essex in the United Kingdom. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2005;11:130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ctnm.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grenfell A. Patel N. Robinson N. Complementary therapy general practitioners’ referral and patients’ use in an urban multi-ethnic area. Complement Ther Med. 1998;6:127–32. doi: 10.1016/S0965-2299(98)80004-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson G. White A. Livingstone R. Do general practices which provide an acupuncture service have low referral rates and prescription costs? A pilot survey. Acupunct Med. 2008;26:205–13. doi: 10.1136/aim.26.4.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orpen M. Harvey G. Millard J. A survey of the use of self-acupuncture in pain clinics – a safe way to meet increasing demand? Acupunct Med. 2004;22:137–40. doi: 10.1136/aim.22.3.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry R. Dowrick C. Homeopathy and general practice: an urban perspective. Br Homeopath J. 2000;89:13–6. doi: 10.1054/homp.1999.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry R. Dowrick CF. Complementary medicine and general practice: an urban perspective. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8:71–5. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2000.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price J. White A. The use of acupuncture and attitudes to regulation among doctors in the UK – a survey. Acupunct Med. 2004;22:72–4. doi: 10.1136/aim.22.2.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross S. Simpson CR. Mclay JS. Homoeopathic and herbal prescribing in general practice in Scotland. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:647–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas KJ. Fall M. Access to complementary medicine via general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas KJ. Coleman P. Nicholl JP. Trends in access to complementary or alternative medicines via primary care in England: 1995–2001. Results from a follow-up national survey. Fam Pract. 2003;20:575–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White AR. Resch KL. Ernst E. Complementary medicine: use and attitudes among GPs. Fam Pract. 1997;14:302–6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/14.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyllie M. Hannaford P. Attitudes to complementary therapies and referral for homoeopathic treatment. Br Homeopath J. 1998;87:13–6. doi: 10.1016/S0007-0785(98)80004-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ernst E. Manipulation of the cervical spine: a systematic review of case reports of serious adverse events, 1995–2001. Med J Aust. 2002;176:376–80. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terrett AGJ. Current concepts in vertebrobasilar complications following spinal manipulation. 2nd edn. Des Moines: JCMIC Group; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst E. Adverse effects of spinal manipulation: a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2007;100:330–8. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.100.7.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith WS. Johnston SC. Skalabrin EJ, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy is an independent risk factor for vertebral artery dissection. Neurology. 2003;60:1424–8. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000063305.61050.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ernst E. How much CAM is based on good evidence? Focus Altern Complement Ther. 2010;15:193. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7166.2010.01043.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sehon S. Stanley D. Applying the simplicity principle to homeopathy: what remains? Focus Alt Complement Ther. 2010;15:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chanda P. Furnham A. Does homeopathy work? Part I: A review of studies on patient and practitioner reports. Focus Alt Complement Ther. 2008;13:82–9. doi: 10.1211/fact.2008.0005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ernst E. Questions about informed consent in complementary and alternative medicine. Focus Alt Complement Ther. 2000;5:183–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith K. Why homeopathy is unethical. Focus Alt Complement Ther. 2011;16:208–11. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7166.2011.01109.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ernst E. Complementary and alternative medicine education – an unmet need. Focus Alt Complement Ther. 2003;8:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colquhoun D. Science degrees without the science. Nature. 2007;446:373–4. doi: 10.1038/446373a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanderson S. Tatt LD. Higgins JPT. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:666–76. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]