Abstract

The outcome of transition from paediatric to adult care is often judged by what happens after transfer. Young people at the point of transfer are reported to have low levels of knowledge and independence. These observations could be interpreted in one of two ways: either that the transition process before transfer is inadequate or that the transition process needs to continue into young adulthood and therefore adult care. The second interpretation is further supported by brain development continuing into the third decade. There is also growing evidence for the effectiveness of young adult clinics in the process of transition. To optimise transition, adult physicians need not only to work with paediatricians to achieve continuity during transfer, but also to look critically at their service as to how it can be changed to meet the needs of young people. In addition, they need to develop knowledge, skills and attitudes to communicate effectively and address a young person's developmental and health needs.

Key Words: transition, adolescents, young adults, age appropriate care

Introduction

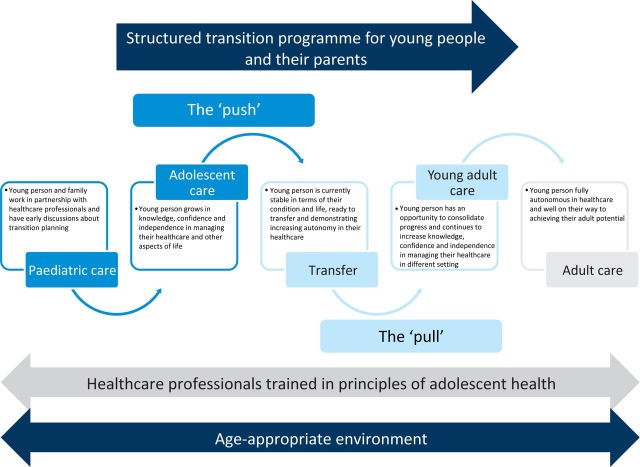

Transition has been described as ‘a multi-faceted, active process that attends to the medical, psychosocial and educational/vocational needs of adolescents as they move from child-centred to adult-orientated care’.1 There is evidence that optimal transition is not being achieved for a significant proportion of young people. The recent report from the Children and Young People's Health Outcome Forum (CYPHOF) states that transition services in the UK need to adopt ‘an approach combining both a pull (from adult care) as well as a push (from paediatrics)’.2 Adult physicians need to know how to ‘pull’ effectively to provide a service that meets the needs of young people transferring into their care (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Transition process from paediatric to adult care: the ‘push’ and ‘pull’.

Transition does not end at transfer

Transition is a process and, although most literature focuses on the process up to transfer to adult services, it is after transfer that outcomes of transition are judged. Studies have shown that young people drift away from adult care and suffer deteriorating health. We suggest that it is time to focus on the transition process continuing beyond transfer, into young adulthood. This approach is further supported by evidence from neuroscience that the brain continues to develop into the third decade, with implications on thought processing and risk taking.3 The extension of transition into young adulthood allows additional time for young people to become autonomous in their healthcare and achieve their full adult potential, the latter potentially delayed or disrupted by growing up with a chronic condition. Adult physicians need not only to aim for continuity of care with paediatric colleagues, but also to adapt their skills and services to meet the young person's changing needs.

Working with paediatricians

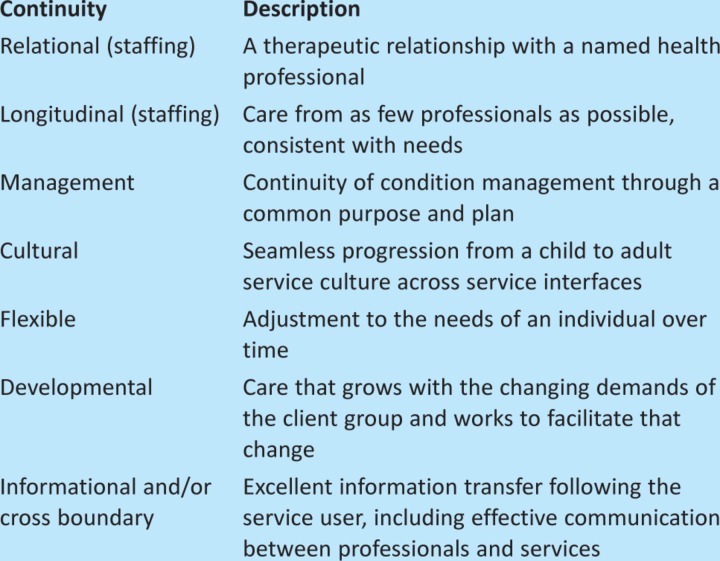

A recent survey of paediatric and adult gastroenterologists found differing perceptions of whether young people were prepared at the time of transfer; the main areas of concern were lack of knowledge and self advocacy.4 By developing close working relationships, the responsibility is shared for how young people are prepared for transfer. Transition policies should be drawn up with a shared goal of continuity across a number of domains (Table 1).5

Table 1.

Domains of continuity in the process of transition.5

Interventions to support transition

Structured transition programme

A UK-based multicentre study in rheumatology found that a structured transition programme with individualised transition planning was associated with improved quality of life.7 Such programmes should be multidimensional (Box 1),6 including condition-specific and generic health education and skills training which have been found to be associated with improved clinical outcomes in the majority of transition studies.7 Starting the programme during early adolescence (aged 11) was associated with the greatest gains in knowledge.6

Box 1. Multidimensional areas included in structured transition programme (adapted with permission, from McDonagh et al. 2007).6

Disease-specific information

Autonomy in healthcare, including lone consulting

Roles of healthcare professionals and differences between paediatric and adult care

Plans for transfer

Body image, growth and puberty

Peer support, bullying and disclosure

Independent living

Education and vocation

Generic health issues, including diet, dental health, exercise, drugs and alcohol, sexual health, in addition to driving and trips away from home

Information-seeking strategies and internet safety

Introducing the adult team

Transition clinics jointly run by paediatric and adult teams were associated with positive outcomes in only three out of eight studies.7 Although meeting the adult team prior to transfer is undoubtedly seen as a positive, careful organisation is required to ensure that young people are not overwhelmed by multiple people in the consultation and left unsure as to who has management responsibility.5 Joint clinics could either be age-banded, enabling young people to be seen over a period of time in a young person-friendly environment with their peers, or for the purpose of handover with one (or several) appointments providing an opportunity for the paediatric team to introduce the young person to the adult team. Where an age-banded or handover clinic is not possible, transfer could be organised to their local adult clinic, with ‘back-up’ appointments at the paediatric clinic that continue to run until the young person feels settled and at ease with the new environment. Arranging visits to the adult service before transfer might also be welcomed by the young person, and many services offer ‘look around’ adult inpatient facilities if a young person is likely to make use of these in the near future.

Transition coordinators

A role spanning paediatric and adult services could fulfil a valuable integrating function. In two out of three studies, the presence of a transition coordinator was associated with positive benefit.6 The role could be fulfilled by an administrator who could assist young people in navigating the healthcare system, a healthcare professional who could provide holistic care, or a professional with skills in working with young people.

Identifying young people ready for transfer

Identifying the readiness of a young person for transfer is challenging and an area of current research. Confidence and skills to manage independent hospital visits, greater perceived independence during consultations, a more positive attitude toward transition and who reported more discussions related to future transfer were found to be associated with young people being ready to transfer.8 Ideally, transfer should not occur during a flare up of the condition or medication change, or if there is upheaval in the young person ’s life in general. Transfer summaries should be written and agreed with the young person and should provide information about them, their condition, past and present investigations, management and treatment. Information regarding ways of making contact with the adult service should also be provided.

Adapting adult services

Ask young people what they want

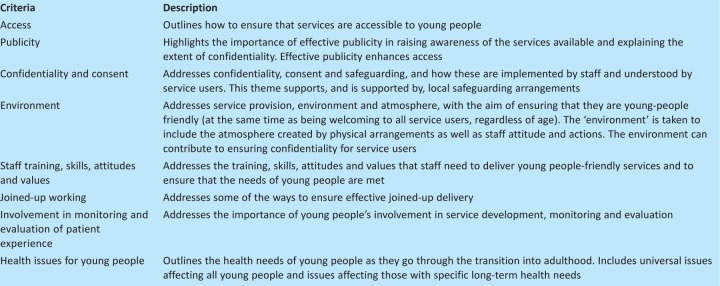

One easy way to decide how adult services should be adapted is to ask young people. Participation by young people can be encouraged in many ways to the benefit of services and young people alike. The RCPCH have produced a document called ‘Not just a phase ’ detailing the ways that participation can be used effectively.9 Involving young people is one of the criterion in the Department of Health (DoH) ‘You're Welcome Quality Criteria’, which sets out ways that services can be adapted to become young person friendly (Table 2).10,11 This document has been used in some regions in the UK to support commissioning negotiations for young people's services.

Table 2.

You're Welcome Quality Criteria for young person-friendly health services.10

Young adult clinics

In a recent systematic review on transition, three out of four studies showed that running a clinic specifically for young adults in the adult setting was beneficial.7 Renal transplantation services have recently published their experience of setting up a young adult clinic: benefits included improved adherence and engagement with healthcare, resulting in reduced transplant failure rates.12 Young adult clinics provide an opportunity for contact with peers and to settle into the new environment. Consideration should be given to: improving accessibility by running clinics in the afternoon to early evening, allowing young people to be seen out of school and/or college hours and miss less time from work; providing longer appointments to allow time for lone consulting and psychosocial screening; and reviewing the standard adult ‘did not attend’ policy is key so that young people are not discharged for non-attendance without exploring the reasons why.

Young people as inpatients

The first experience of adult services for a young person might be during an inpatient admission. Hospital admissions for chronic conditions (eg diabetes, epilepsy or asthma) have increased in 10–19-year olds by 26% over the past 7 years.13 Young people on adolescent wards (compared with adult wards) were more likely to report excellent overall care, feeling secure, having confidentiality maintained, feeling treated with respect, confidence in staff, appropriate information transmission and appropriate involvement in own care.14 However, dedicated adolescent inpatient facilities currently do not exist in most centres. Therefore, the focus needs to be on providing age-appropriate care through staff training, flexible visiting so that family or friends can provide support, nursing young people with those of similar age and providing dedicated social areas for young people. For young people who are likely to require inpatient admissions, arranging visits to adult services to meet staff and providing information about day-to-day and expected acute care, as well as wants and needs, should be part of transition planning. This is particularly important for young people with conditions that are not frequently seen on adult wards and those with learning difficulties and/or complex disability.

The first consultation and beyond

Young people and parents have identified that the quality of their relationship with a healthcare professional is important (reference 15). Surveys of UK adult physicians demonstrate that lack of training is a significant barrier to providing age appropriate care.4,16 Work is underway through the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) to improve training of future adult physicians in the care of adolescents and young adults. Useful approaches are detailed below and training resources are available, including the Adolescent Health elearning Programme, which is free to all NHS employees (www.rcpch.ac.uk/AHP).

Continuity and confidentiality

Key to the relationship with the adult physician is continuity. Young people have reported that it takes at least four to five visits before they trust a particular doctor.17 If continuity is actively promoted, 77% of young people with diabetes were less likely to be hospitalised following transfer to adult care.18

Young people have a right to confidentiality. Concerns about confidentiality can deter young people from consulting their doctors: this is particularly true for older adolescents and young women.19 Adult physicians should take the time to explain about confidentiality and it's limits at the first consultation and not assume that it is fully understood. The DoH You're Welcome Quality Criteria recommends displaying information about confidentiality in clinics for young people.10

Parents and lone consulting

For parents of children who have been unwell, particularly for those who have had a serious long-term health condition, the shift from care-giving to providing advice and support when needed is difficult.20 The consultation is an opportunity for parents to satisfy their information needs and provide ongoing support for their child. Navigating this can be challenging for adult physicians. It is important to balance the information needs of parents and acknowledge their role,21 while ensuring that the young person recognises that the process revolves around them.

Actively encouraging lone consulting with the young person for part, or all, of the clinic appointment, is helpful in increasing the confidence of the young person in their own healthcare and facilitating changes in the parental role.22 Lone consulting has been associated with improved quality of life, readiness for transition and more successful transfer.15 However, surveys have shown that less than half of all adult physicians see young people on their own.23

Self-management of chronic conditions

Moving to a new service provides an opportunity for a new start and a new relationship between adult physician and young person. At the beginning of this relationship, the adult physician should remain open and ‘assume nothing’. A young person's knowledge about their condition can be low,4 so exploring this is important. Finding out what the young person finds most difficult about having their condition and how it affects their life is a good starting point. Poorly developed abstract thinking can affect a young person's ability to plan for the future, which might affect motivation and ability to self-manage, including adherence with medication. Therefore, focus should be placed on short-term benefits.

Psychosocial screening and health promotion

Psychological and social development are an important consideration in this age group. Young people with chronic conditions are at risk of not fulfilling their potential as adults.24,25 It is during adolescence that ‘risky’ health behaviours develop that can continue into adult life; such behaviours are reported to be more common in young people with chronic conditions compared with their healthy peers.26

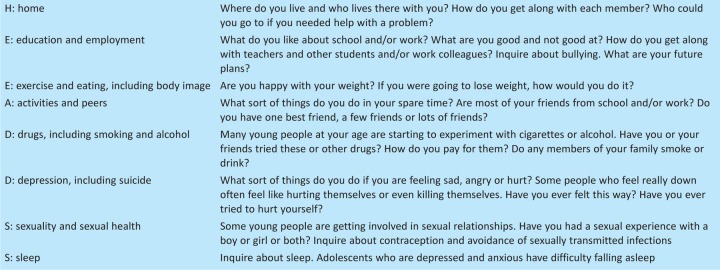

Using a psychosocial screen enables the adult physician to adapt their consultation to address both developmental aspects and health behaviours, and provides an opportunity to develop a rapport with the young person. The ‘HEEADDSS psychosocial interview for adolescents’ is the most widely used interview scheme and covers home, education and employment, eating and exercise, activities, drugs, depression and suicide, sex and sleep (Table 3).27 Confidentiality needs to be raised at the outset and parents and other adults should not be present. Using HEEADDSS screening has been shown to be helpful in identifying concerns in up to one-third of patients.28

Table 3.

HEEADDSS: a psychosocial interview (adapted with permission).27

Adult physicians might feel that they do not have all the answers for this age group. Depending on the issue identified providing information and signposting young people to local services or relevant websites (such as www.teenagehealthfreak.org and www.youthhealthtalk.org) may be sufficient.

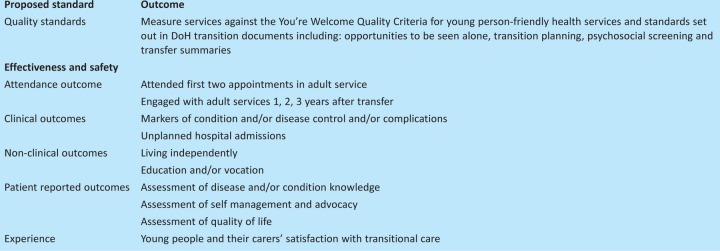

Monitoring outcomes

Ongoing monitoring and evaluation are key to ensure that young people are engaged with healthcare and to guide development of transition and adult services (Table 4).15

Table 4.

Proposed standards and outcomes for monitoring and evaluation of transitional care.15

Support from RCP, specialist societies, associations and healthcare trusts

The RCP has formed a steering group across specialities to focus on the needs of this age group and of adult physicians in caring for them, with a focus on training, clinical governance, standards, aspects of service delivery, and public and patient involvement. Specialist societies and associations can also have a key role in identifying needs within their specialty and their patient population (Box 6). For example, Together for Short Lives, a national charity involved in care of children and young people with palliative care needs, has published and rolled out ‘The Transition Care Pathway’.29 Trusts, in association with commissioners, need to agree on which interventions can be delivered across specialties to optimise transition. Adding transition and age-appropriate care to the new outcome framework, as recommended by the CYPHOF, would protect and facilitate development in this area.2

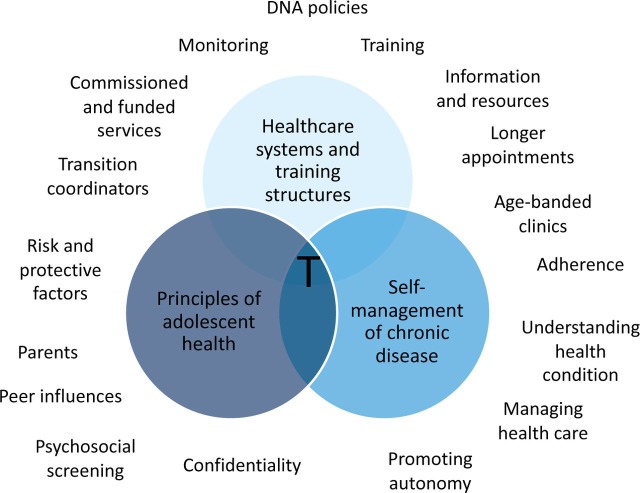

Summary

The adult physician is in an ideal position to improve transition for young people with chronic conditions. Transition does not stop at transfer but continues into young adulthood and through the early years of attending the adult service. It should be considered complete only at the point that the young person has achieved their adult potential for independence in healthcare and self-management. To optimise transition and age-appropriate care (Fig 2), adult physicians need not only to work with paediatricians to achieve continuity during transfer, but also to look critically at their service as to how it can be changed to meet the needs of young people. They also need to develop knowledge, skills and attitudes to communicate effectively and address a young person's developmental and health needs.

Fig 2.

Summary of essential elements for age-appropriate care transition. 30 T = transition.

References

- 1.Blum RW. Garell D. Hodgman CH, et al. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14:570–6. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90143-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Children and Young People's Health Outcomes Forum. Report of the Children and Young People's Health Outcomes Forum. London: Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg L. A behavioral scientist looks at the science of adolescent brain development. Brain Cogn. 2010;72:160–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sebastian S. Jenkins H. McCartney S, et al. The requirements and barriers to successful transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: differing perceptions from a survey of adult and paediatric gastroenterologists. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:830–44. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen D. Cohen D. Hood K, et al. Continuity of care in the transition from child to adult diabetes services: a realistic evaluation study. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17:140–8. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.011044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonagh JE. Southwood TR. Shaw KL. British Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology. The impact of a coordinated transitional care programme on adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology. 2007;46:161–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowley R. Wolfe I. Lock K. McKee M. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:548–53. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.202473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Staa A. van der Stege HA. Jedeloo S, et al. Readiness to transfer to adult care of adolescents with chronic conditions: exploration of associated factors. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Not Just a Phase – a guide to the participation of children and young people in health services. London: RCPCH; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health. You're Welcome quality criteria: making health services young people friendly. London: DH; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hargreaves D. Mcdonagh J. Viner R. Validation of You're Welcome Quality Criteria for Adolescent Health Services using data from national inpatient surveys in England, J Adolesc Health. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Harden PN. Walsh G. Bandler N, et al. Bridging the gap: an integrated paediatric to adult clinical service for young adults with kidney failure. BMJ. 2012;344:e3718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coleman J. Brooks F. Treadgold P. Key data on adolescence 2011. London: Association of Young People's Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viner RM. Do adolescent inpatient wards make a difference? Findings from a national young patient survey. Pediatrics. 2007;120:749–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gleeson H. Turner G. Transition to adult services. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2012;97:86–92. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonagh JE. Southwood TR. Shaw KL British Paediatric Rheumatology Group. Unmet education and training needs of rheumatology health professionals in adolescent health and transitional care. Rheumatology. 2004;43:737–43. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klostermann BK. Slap GB. Nebrig DM, et al. Earning trust and losing it: adolescents’ views on trusting physicians. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:679–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakhla M. Daneman D. To T, et al. Transition to adult care for youths with diabetes mellitus: findings from a Universal Health Care System. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1134–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlisle J. Shickle D. Cork M. McDonagh A. Concerns over confidentiality may deter adolescents from consulting their doctors. A qualitative exploration. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:133–7. doi: 10.1136/jme.2004.011262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kieckhefer GM. Trahms CM. Supporting development of children with chronic conditions: from compliance toward shared management. Pediatr Nurs. 2000;26:354–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen D. Channon S. Lowes L, et al. Behind the scenes: the changing roles of parents in the transition from child to adult diabetes service. Diabet Med. 2011;28:994–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Staa A On Your Own Feet Research Group. Unraveling triadic communication in hospital consultations with adolescents with chronic conditions: the added value of mixed methods research. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82:455–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suris JC. Akre C. Rutishauser C. How adult specialists deal with the principles of a successful transition. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:551–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frobisher C. Lancashire ER. Winter DL, et al. Long-term population-based marriage rates among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Britain. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:846–55. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dugueperoux I. Tamalet A. Sermet-Gaudelus I, et al. Clinical changes of patients with cystic fibrosis during transition from pediatric to adult care. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:459–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suris JC. Michaud PA. Akre C. Sawyer SM. Health risk behaviors in adolescents with chronic conditions. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1113–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldenring J. Cohen E. Getting into adolescent heads. Contemp Paediatr. 1988;5:75–90. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson H. Bostock N. Phillip N, et al. Opportunistic adolescent health screening of surgical inpatients. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:919–21. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-301835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Association for Children's Palliative Care. The Transition Care Pathway. Vol. 2011. Bristol: ACT; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy A. Sawyer S. Transition from paediatric to adult services: are we getting it right? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:403–9. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328305e128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]