ABSTRACT

Digital technology in the early 21st century has introduced significant changes to everyday life and the ways in which we practise medicine. It is important that the ease and practicality of accessing and disseminating information does not intrude on the high standards expected of doctors, and that the boundaries between professional and public life do not become blurred through the increasing adoption of social media. This said, as with any such profound disruption, the social media age could be responsible for driving a new understanding of what it means to be a medical professional.

KEYWORDS: Social media, good medical practice, GMC, professionalism, Twitter

Introduction

Consider the amount of time one spends attending to a mobile computing device. The range of functions and information that can be tapped into extremely quickly while at the bedside or in the clinic are immense. Only a few years ago this would have been inconceivable. Now web-based resources such as Medscape, BMJ Best Practice and Doctors.net are available, all of which provide a wealth of insight and factual information that can support and augment clinical practice. This ready access has arguably even started to change the way we think and process information.1 This is game changing, given that traditional medical training is often depicted as ‘memorising long lists of stuff’. Ultimately, it will impact on the professional identity of doctors, should medicine move from a culture of internalising, managing and applying learning, to practitioners who forgo knowledge acquisition, to those who rely instead on mobile devices that afford access to relevant guidelines at the right time from a variety of sources.2

The ubiquitous smart phone has facilitated unprecedented communication with the wider world, via social media (Box 1). New terminology has emerged, which often seems impenetrable to the uninitiated, as individuals use dedicated apps to update their status on their Facebook newsfeed, retweet messages of note on Twitter, or share video clips and promote medical services on Vimeo (Table 1).

Box 1.

Social media definition.

| Social media describes web-based applications that allow people to create and exchange content. We use the term to include blogs and microblogs (such as Twitter), internet forums (such as Doctors.net), content communities (such as YouTube and Flickr), and social networking sites (such as Facebook and LinkedIn).3 There is also the concept of ‘one to many users’ – a document or piece of media that can be edited by two or more geographically separate individuals, hosted by a web-based service such as Google Drive or Dropbox. |

Table 1.

Examples of social media content for doctors

| Social media content | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| A microblogging messaging website that allows communications using 140 characters or less. Twitter feeds are updated every time a new message is posted or linked to a new contact or retweeted by followers. | @RCPLondon @ABCD @BMJ_latest @OxfMedSci @MedicalReg #TipsForNewDocs @BenGoldacre #FOAMed #MedEd | |

| Websites | There are a large variety of social media websites, including blogs, bulletin boards and discussion forums. | www.facebook.com/resilientgp www.doctorshangout.com www.physicianspractice.com www.rcemfoamed.co.uk/ |

| SERMO | A USA-based ‘private’ social network for doctors | Website quote about why doctors love SERMO: ‘I can speak freely because I am anonymous. I don't have to worry about my words getting back to a hospital administrator’ |

| The world's largest professional social network with 300 million members, which allows networking, interaction and communication, from business deals to new ventures. | The top 25 doctors: www.linkedin.com/title/doctor Imperial College London endocrinology discussions: www.linkedin.com/groups/5159178/profile Society of Physician Entrepreneurs (https://www.linkedin.com/groups/917937/profile) | |

| Vimeo | A video hosting and sharing website in which users can upload, share and view videos. | Activ Doctor Online https://vimeo.com/activdoctorsonline/videos Médecins Sans Frontières https://vimeo.com/user12791481 |

Such activity, however, can carry implications for the professional sphere. The General Medical Council (GMC) has already highlighted the potential for problems in maintaining good medical practice (Box 2), releasing specific guidance on the subject in 2013, and advising that ‘the standards expected of doctors do not change because they are communicating through social media’.3 In this article, we review the implications of this guidance, which is of particular relevance to newly qualified physicians, and provide a broad overview to those entering the social media domain for the first time.

Box 2.

Good medical practice.3

| > You must treat colleagues fairly and with respect. |

| > You must make sure that your conduct justifies your patients’ trust in you and the public's trust in the profession. |

| > When communicating publicly, including speaking to or writing in the media, you must maintain patient confidentiality. You should remember when using social media that communications intended for friends or family could become more widely available. |

| > If you are faced with a conflict of interest, you must be open about the conflict, declaring your interest formally, and you should be prepared to exclude yourself from decision making. |

Benefits versus risks

The main benefits include the rapid dissemination of new developments and ideas, development of communities of practice and crowd sourcing of advice on challenging medical situations and cases. There is the collective opportunity for instant response and debate on issues of interest or controversy. Further benefits include publicity, the ability to advertise meetings, position statements, links to surveys and interactions beyond one’s local base. Professional organisations can build relationships between clinicians and with patients for grassroots input and respond to their views as never before; accessing ‘the cloud of patient experience’ could be a powerful means of transforming poor-quality care.4

In the USA, SERMO is an anonymised, private social network for doctors, with testimonials including ‘The ability to share thoughts and concerns about work, family, patients and life with those that are most likely to understand is incredibly helpful’ and ‘I find SERMO to be very useful both clinically and non-clinically. Being a semi-anonymous environment actually allows for more honest and useful advice and comments. I get enough daily BS, PC crap in real life. I don’t need more in the virtual life.’

On Twitter, use of hashtags allows users to link their tweets according to shared content or themes – eg #notsafenotfair. The resulting ability to connect large networks of like-minded doctors and researchers, coupled with generally much improved access to information, is particularly valued. Communities of practice have emerged, notably in supporting continuing medical education (#MedEd).5 The emergency and acute medical specialties have been quick to embrace social media as a platform for learning, coining the phrase ‘free open access meducation’ (#FOAMed). Individual clinicians have gained prominence through their insights and commentary: for example, Dr Helgi Johannsson (@traumagasdoc), a consultant anaesthetist at Imperial College, regularly tweets tips and teaching points for students and trainees to develop their knowledge base, using #TGDed.

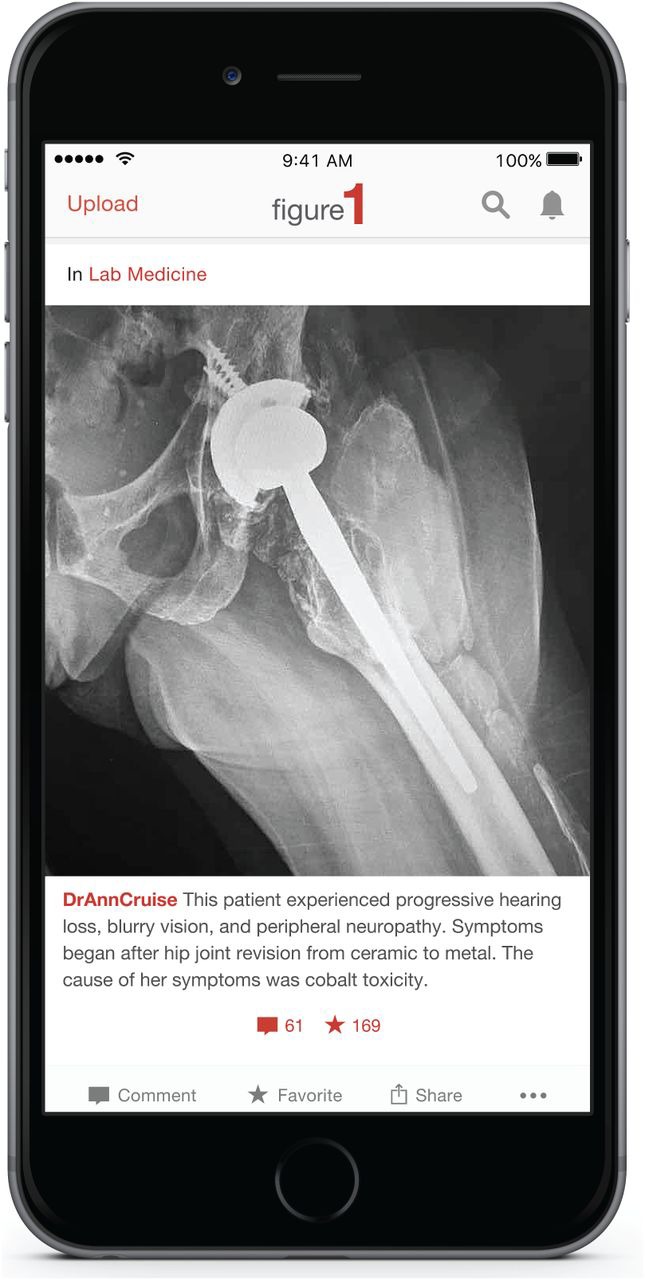

The latest app to gain popularity, Figure 1, goes even further. Doctors can upload anonymised descriptions and photos of unusual patient presentations for education purposes (with patient consent). The app then allows other doctors to comment and provide input, improving the speed and accuracy of diagnosis (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

The Figure 1 medical app.

In terms of the risks, there are the problems of personal–professional boundary crossing, threats to patient confidentiality and potential undermining of the public's confidence in the medical profession. Maintaining a recognisable online presence can introduce difficulty in separating professional and personal identities.

For medical students, whose adolescence has been defined by the connectivity achieved through the online world and social media, the transition to a professional status that precludes acceptance of friend requests from patients on Facebook might require robust reinforcement. Such scenarios have provoked specific guidance. In the instance of a patient contacting a doctor via their personal profile, the GMC advises doctors to clearly indicate that social and professional relationships cannot be mixed and direct them to a professional point of contact. There are also the risks of unintentionally violating patient confidentiality, denigrating of colleagues or the public, exposing conflicts of interests or undermining trust in the profession overall.

As is often the case in medicine, significant grey areas exist. At what point does an individual seeking information become a patient? Because many online profiles are anonymous, should doctors require individuals to identify themselves before engaging in discussion, to avoid the possibility of crossing this boundary? Could such approaches disrupt social media’s potential as a tool for public health education and information sharing? Although the GMC acknowledges the benefit of doctors using social media,3 these are challenges that generations of doctors approached by friends or relatives for informal advice have grappled with, now transplanted to a more public and permanent forum.

The GMC guidance for doctors

Confidentiality

As a priority, patient confidentiality must be protected throughout online interactions. Regardless of the privacy settings that users employ on their personal profiles, social media sites cannot guarantee that shared content will remain confidential and protected from unauthorised access (hacking), meaning that patients, colleagues, employers, potential employers, and other organisations could be able to view this data. Information about location is often embedded in photos, and individuals may be tagged. Even if a single post has been censored carefully to avoid breaching confidentiality, combining multiple posts could still render an individual identifiable.

There is a nominal difference between openly accessible and closed social media – where access is encrypted and gated to restrict non-medical viewers (and where leakage of information would be seen as a breach of confidentiality). Comment can be passed among peers, and it is an arena in which expressing ignorance, challenging diagnoses and dissent on controversial medical matters can be seen as useful as part of a private global multidisciplinary team meeting. Such comments are best avoided in truly open social media. However, even on a closed site, once published online, content may be commented on, further distributed, downloaded to private file servers, or captured as an image of the original post, rendering it difficult, if not impossible, to remove entirely. Some doctors may conclude that it is safest to avoid posting potentially risky material altogether. That one should not share patient-identifiable information in a public space at the risk of being overheard is well understood; the internet is no exception.

Respect for colleagues

The same question of content permanence can impact on the professional duty of fairness and respect that doctors must maintain in their relationship with their colleagues, as outlined in good medical practice. As above, an ill-judged comment detailing an individual’s frustrations, shared between friends, could yet be accessible and circulated more widely, potentially to the original subject’s awareness. It is worth remembering that online posts relating to individuals or organisations are subject to the same laws of copyright and defamation as other forms of communication.

Anonymity and conflicts of interest

One of the more controversial recommendations by the GMC is that users identifying themselves as doctors in their public profiles should always do so by name, so as to remain accountable. Some doctors might feel that this infringes on their right to free expression and a private life, distinct from their professional identity. The GMC proposes, however, that content posted by a medical practitioner is likely to be received and interpreted differently by the general public from that uploaded by others, and could be assumed to represent the position of the profession. Here too, internet usage leaves a digital trail that can often be traced to its original source, undermining the premise of anonymity anyway. Transparency is similarly required of doctors in declaring any conflict of interest related to material they have shared online, particularly if this material could be interpreted as of financial benefit to the individual. Evidence from a systematic review suggests that such interests could skew medical decision making.6 This process has been rendered straightforward by the online, open-access, voluntary register of doctors’ declared interests.7 The duty to behave responsibly in public forums, as per good medical practice, applies throughout.

Redefining professionalism?

It is recognised that, although failures in professional behaviour, confidentiality and declaring conflicts of interest have all been observed online, these are rare occurrences.8 Nevertheless, the medical literature surrounding use of social media has been dominated by expressions of concern, with less attention paid to the potential enhancements to medical practice and professional development.9 The GMC has embarked on a succession of consultation events across the UK,10 and with publication of its findings about the current and projected state of medical professionalism expected in 2016, perhaps a more nuanced understanding will yet emerge. New forms of social media continue to flourish, predominantly in response to an empowered youth-driven demand for improved interpersonal connectivity (unpublished data).

After initial scepticism, the field is increasingly recognised as a valid topic for health research. In time, this ongoing disruption could have profound implications. Provided that public trust in the profession is maintained, the traditional boundaries determining what it means to be a medical professional in the 21st century may prove more flexible than current guidance imposes. After all, ‘the most important question may not be how to protect professionals online but, rather, how social media can open new debates about medical professionalism for better patient care and healthier societies’.9

Conclusions

Medical professionals in the internet age need to be cognisant of the ways in which they use social media and, for now, ensure a clear divide between public and private behaviour. Unintentional slippages in good medical practice and past mistakes can be unforgivably magnified and widely disseminated before having a chance to be recalled, so caution, common sense and enhanced sensitivity regarding what it means to act professionally are perhaps best advised. We should remain aware though that the public expectation of medical professionals, as with many institutions and authority figures, could be changing. The profession must continue evolving, as it always has, in response to demand and new technologies.

Conflicts of interests

NC is an education associate with the GMC and tweets under the moniker @NicholasCork. PG is the editor-in-chief of the British Journal of Diabetes and tweets under the moniker @BJDVD_Editor.

References

- 1.Thompson C. Smarter than you think. How technology is changing our minds for the better. London: William Collins; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace S. Clark M. White J. ‘It’s on my iPhone’: attitudes to the use of mobile computing devices in medical education, a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001099. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.General Medical Council Doctors’ use of social Media. London: General Medical Council; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greaves F. Ramirez-Cano D. Millett C. Darzi A. Donaldson L. Harnessing the cloud of patient experience: using social media to detect poor quality healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:251–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheston CC. Flickinger TE. Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88:893–901. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ffc23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spurling GK. Mansfield PR. Montgomery BD, et al. Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians’ prescribing: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Who pays this doctor A voluntary register of doctors’ declared interests. Available online at www.whopaysthisdoctor.org/ [Accessed 7] April 2016].

- 8.Chrétien KC. Azar J. Kind T. Physicians on twitter. JAMA. 2011;305:566–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenwick T. Social media and medical professionalism: rethinking the debate and the way forward. Acad Med. 2014;89:1331–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.General Medical Council Medical professionalism matters. http://www.gmc-uk.org/about/26365.asp. (Accessed 7) April 2016.