ABSTRACT

There are three neurological syndromes that may follow malarial infection after recovery and at a time when the patient is aparasitaemic. An acute disseminated encephalopathy; a cerebellar syndrome; and an acute demyelinating polyneuropathy. This paper reports a 42-year-old male patient who developed encephalopathy.

KEYWORDS: Plasmodium falciparum malaria, post-malaria syndromes, encephalopathy

Introduction

There are three neurological syndromes that may occur after recovery from malaria, with no parasitaemia, usually following Plasmodium falciparum malaria and occurring after an interval of 2 days to 2 months. The syndromes are an acute disseminated encephalopathy, known as post-malaria neurological syndrome (PMNS); a delayed cerebellar syndrome; and an acute idiopathic demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP). These syndromes may follow recovery from an attack of falciparum malaria with no parasitaemia,1 and more commonly occurs after treatment with mefloquine.1

Case history

A 42-year-old right-handed commercial airline pilot, who spent one night in West Africa, had a mosquito bite on his left arm while having a drink in the evening at the hotel poolside. He had applied a topical anti-mosquito repellent containing diethyltoluamide (DEET), but he had not taken any oral anti-malarial prophylactic medication. Five days later he became unwell with flu-like symptoms and headache. These symptoms progressed over the next 3 days, and following his return home he attended his GP. Malaria was suspected and he was admitted to hospital where P falciparum malaria was confirmed with a parasitic load of 5.6%. He spent 5 days in the intensive care unit, treated with intravenous quinine for 2 days then oral quinine, oral doxycycline and an exchange transfusion. Complications included renal impairment with a raised urea and creatinine, anaemia, thrombocytopenia and meralgia paraesthetica. He was discharged after 8 days on ferrous fumarate and omeprazole. When seen as an outpatient 9 days later, he was found to be anaemic (haemoglobin 10.7 g/dL, red blood cells (RBC) 3.75x1012/L, haematocrit (HCT) 3.323) with a raised urea (8.4 mmol/L) and creatinine (126 μmol/L). No malarial parasites were seen on blood films; however, a malaria antigen screen was positive. Three weeks later his haemoglobin had risen to 12.5 g/dL (RBC 4.2x1012/L, HCT 3.57), his urea was 4.9 mmol/L and creatinine 109 μmol/L. There were no medical sequelae 1 month after the initial symptoms of malaria and he returned to his job as a pilot.

A few days later, following a satisfactory aircraft simulator check, he flew to South America. He returned to the UK 3 days later and on the same day he flew to Europe on a short-haul flight, returning the following day. The next day he travelled by bus and train to attend a wedding and remembers having a drink in the hotel bar late that night and then no clear memory for about 1 week. There are no corroborated details of his whereabouts for the next 24 hours; however, it appears that the next day he travelled to the local airport, but was clearly confused and disorientated. An ambulance was called and he was admitted to hospital.

A diagnosis of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) was made and he was treated with ceftriaxone, acyclovir, intravenous methylprednisolone for 3 days followed by 60 mg prednisolone orally, tapering over 6 weeks.

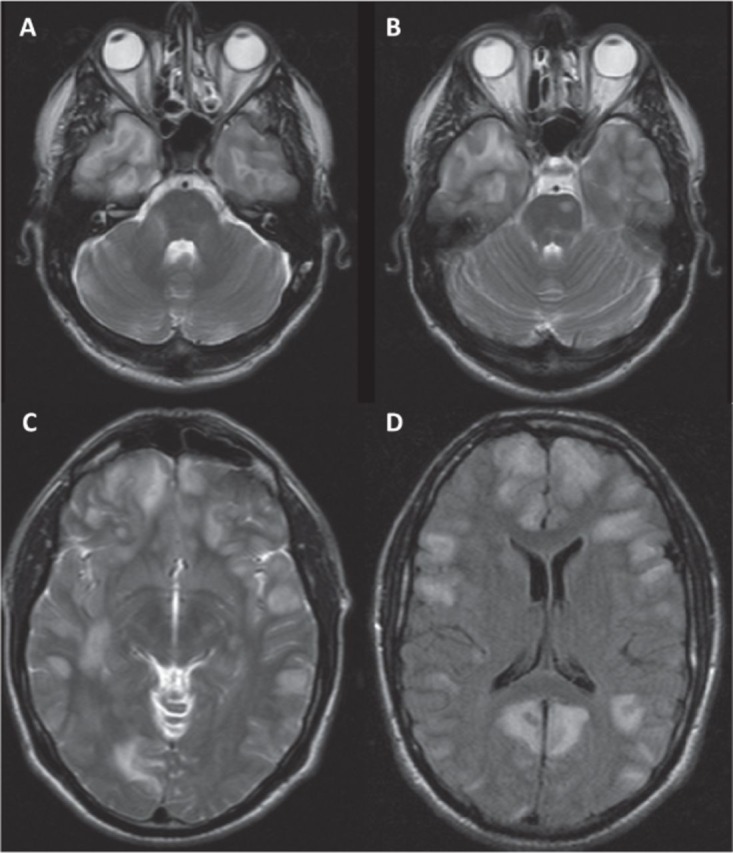

A non-contrast computerised tomography brain scan the day after admission and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast 11 days later both showed very widespread lesions with moderately large confluent areas throughout both cerebral hemispheres, predominantly in the white matter (Fig 1). There were also lesions in the basal ganglia, right thalamus, brain stem and cerebellum, many of which enhanced after contrast.

Fig 1.

A – Axial T2 MRI 5 mm showing extensive temporal lobe lesions; B – Axial T2 MRI 5 mm showing brain stem lesion; C – Axial T2 MRI 5 mm showing very widespread predominantly white matter lesions throughout both hemispheres; D – T2 flair MRI 5 mm showing very widespread predominantly white matter lesions throughout both hemispheres. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

He slowly improved clinically and after 16 days was transferred to a rehabilitation unit, still confused with cognitive, memory and communication difficulties. He was discharged 6 weeks later. One month after leaving the rehabilitation unit he passed the Rookwood Driving Battery, achieving maximal scores and 3 months later he passed an aircraft simulator check without any difficulties and did so again 1 year later. Serial MRIs performed over this time showed progressive improvement. 18 months after the resolution of the symptoms of encephalopathy he returned to his role as a pilot with a co-pilot restriction.

Discussion

The World Health Organization estimates that in 2015 there were 214 million cases of malaria worldwide, with 438,000 deaths.2 Malaria is endemic in 97 countries with 3.2 billion people at risk, and 1.2 billion at high risk. It is encouraging that there has been a 47% reduction in mortality since the start of this century. Considering this very large number of cases across the world, it is very surprising that PMNS was only first described in 1996,1 and since then there have been fewer than 50 cases reported in the literature, mostly as single case reports. It therefore appears to be an extremely rare complication but it may also be grossly underreported, since a large number of those affected are young children in the developing world and once recovered from malaria, patients may return home and the subsequent illness either not reported or not ascribed to a complication of malaria.

There appear to be three recognised PMNSs, which are defined as a neurological syndrome that develops after recovery from malaria at a time when the patient is aparasitaemic. This nearly always follows P falciparum infection. The first syndrome to be described was delayed cerebellar ataxia in1986,3,4 followed by Guillain–Barré–Strohl Syndrome (AIDP) in 1992,5 and lastly PMNS in 1996.1

The latter report remains the largest and most definitive series with 19 adults and three children identified out of 18,124 patients with falciparum malaria; of whom 1,176 (6.5%) were severely affected. The clinical features of PMNS as defined in this and subsequent reports are: onset at 2–60 days after recovery from P falciparum malaria; mean duration of the encephalopathy was 60 hours (24–240); self-limiting without treatment, though steroids may help. In the acute phase there may be rapid onset of confusion with aphasia, psychosis, myoclonus, epilepsy, visual hallucinations, tremor and ophthalmoplegia. MRI of the brain and spinal cord may be normal or may show widespread white matter lesions. There are no long-term sequelae and the condition does not relapse or recur. Risk factors for developing PMNS include severe P falciparum malaria and treatment with mefloquine, the relative risk compared to treatment with quinine is 9.2 (1.2–71.3; p=0.012).1

There have been two case reports describing brainstem involvement, but without encephalopathy, which satisfy the basic requirements for a PMNS. In one, the onset was 2 days after recovery from P falciparum when the patient was aparasitaemic. The patient was tetraplegic with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and no cerebral lesions; he fully recovered in 3 months.6 The other had an onset 5 days after recovery from P falciparum when aparasitaemic and had cerebellar and brain stem involvement.7 Delayed cerebellar ataxia was first reported in Sri Lanka in 19863 and their experience of 74 patients was described in 1994.4 These followed uncomplicated falciparum malaria and exhibited a midline cerebellar syndrome with no cerebral symptoms. However, 25 patients were still parasitaemic and 12 were still febrile. Since a cerebellar syndrome may occur with P falciparum as part of cerebral malaria, only 49 of these patients would satisfy the basic criteria for a diagnosis of a PMNS.

Guillain–Barre–Strohl Syndrome (AIDP) complicating malaria was first described in 1980.8 A literature search found 12 reports: 8 followed P falciparum and 4 after P vivax malaria. 11 had uncomplicated infections and 1 had had cerebral malaria. The mean delay after recovery from malaria was 14 days (5–42) and three died. Another 10 patients have been reported from the Sudan9 but all while febrile with falciparum malaria; four died from bulbar and respiratory paralysis. It seems that AIDP may occur both as part of the acute malarial infection and as a PMNS. This complication is often associated with a persistent neurological deficit.

PMNS is often described as a form of ADEM; this is an unfortunate association as ADEM may recur or relapse, particularly after stopping steroids (20–30%),10,11 there may be a persisting deficit, and it may subsequently be diagnosed as multiple sclerosis. In contrast, PMNS is a single clinical event, with complete recovery without treatment and no relapse or recurrence.

References

- 1.Nguyen Thi Hoang Mai Day PJ. Chuong LV, et al. Post Malaria Neurological Syndrome. Lancet. 1996;348:917–921.. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)01409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO World Malaria Report. WHO Press; 2015. ISBN 978 92 4 156515 8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Silva HJ. Gamage R. Herath HK. Abeysekara DT. Peiris JB. A delayed onset cerebellar syndrome complicating falciparum malaria. Ceylon Med J. 1986;31:147–150.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senanayaka N. de Silva HJ. Delayed cerebellar ataxia complicating falciparum malaria: a clinical study of 74 patients. J Neurol. 1994;241:456–459.. doi: 10.1007/BF00900965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AIDP

- 6.Pace AA. Edwards S. Weatherby S. A new clinical variant of the post malaria neurological syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2013;334:183–185.. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seneviratne U. Gamage R. Brainstem dysfunction: another manifestation of post-malaria neurological syndrome? Ann Trop Med Parasitology. 2001;95:215–217.. doi: 10.1080/00034983.2001.11813631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padmini R. Maheshwari MC. P.vivax malaria complicated by peripheral neuropathy with electrophysiological studies. J Assoc Physicians India. 1980;28:152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokrab T-G O. Eltahir A. Idris MNA. Hamid M. Guillain-Barre syndrome following acute falciparum malaria. Neurology. 2002;59:1281–1283. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.8.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz S. Mohr A. Knauth M, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a follow-up study of 40 adult patients. Neurology. 2001;56:1313–1318.. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchioni E. Tavazzi E. Franciotta D, et al. Recurrent ADEM versus MS: differential diagnostic criteria. Neurol Res. 2008;30:74. doi: 10.1179/016164107X228615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]