Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is increasingly diagnosed worldwide and is considered to be the most common liver disorder in Western countries. It comprises a disease spectrum ranging from simple steatosis (fatty liver) through non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) to fat with fibrosis and, ultimately, cirrhosis.

Epidemiolotitley

The prevalence of NAFLD assessed by ultrasound is 20–30% in Western adults. NASH is much rarer, affecting 3–16% of healthy living liver donors. NAFLD is strongly associated with the presence and severity of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Studies in severely obese patients (body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2) undergoing bariatric surgery have reported prevalences of NAFLD and NASH of 91% and 37%, respectively.1 The prevalence of NAFLD in T2DM has recently been reported to be 70%.2 Even in the absence of obesity and T2DM, NAFLD is closely associated with other features of the metabolic syndrome.

Natural histotitley

Data from retrospective studies have shown that fibrosis progresses in 38% of patients with NAFLD, with necroinflammation on index biopsy the strongest predictor.3 End-stage NASH accounts for 30–75% of all cases of cryptogenic cirrhosis. About 7% of patients with compensated NASH-related cirrhosis will develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) within 10 years, while 50% will require a transplant or die from a liver-related cause.4 The overall and liver-related mortality of patients with NAFLD is higher than in age- and sex-matched populations, principally due to increased liver and cardiovascular-related mortality.5 Patients with NAFLD have a higher prevalence of micro- and macrovascular disease compared with controls, and increasing evidence supports a direct causal role for NAFLD in the pathogenesis of atheromatous cardiovascular disease.6

Clinical presentatititlen

NAFLD is largely asymptomatic, although fatigue is a significant problem.7 Most patients are diagnosed after they are found to have unexplained abnormalities of liver blood tests, NAFLD accounting for 60–90% of such cases. History should concentrate on determining the presence of conditions associated with NAFLD and on excluding alternative causes of steatosis, including excessive alcohol intake, previous abdominal surgery and drugs such as amiodarone and tamoxifen.

Investigatiotitles

In the absence of advanced disease, routine liver blood tests are either normal or typically show mild elevations of transaminases, alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase. Ultrasound, computed tomography and routine magnetic resonance imaging are all excellent at detecting steatosis, but none can reliably detect NASH or fibrosis. Newer techniques, including proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and transient elastography, show promise but require further study prior to routine use for disease staging.

Liver biopsy is not required for diagnostic purposes in a typical patient. However, it may be indicated for accurate disease staging – of importance because different stages of NAFLD have different prognoses and therefore require different management strategies.8

Non-invasive markers for staging NAFtitleD

Various clinical and laboratory markers have been shown to be associated with advanced fibrosis (bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis) in NAFLD patients, notably:

advanced age (>45–50 years)

BMI > 30kg/m2

T2DM

aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio greater than one.

At present, it would seem reasonable to restrict liver biopsy to patients with at least some of the risk factors. Together with serum markers of inflammation and fibrosis, some risk factors have been combined into a number of different diagnostic algorithms. They all currently require independent validation and comparison before they can be applied to routine clinical practice.8 This is also the case for the recently reported diagnostic test for differentiating NASH from simple steatosis.9

Overall management stratetitley

Current management strategies are directed at treating, where present, the individual components of the metabolic syndrome. This reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease and may also be beneficial for the liver. This is all that is required for patients with simple steatosis who can be managed by general or primary care physicians in view of the largely benign prognosis. In contrast, patients with more advanced NAFLD require long-term follow-up by hepatologists in light of their increased propensity for disease progression.

Rationale for management

The rationale for NAFLD therapies is based on a growing understanding of disease pathogenesis, with a particular focus on:

reducing insulin resistance, hepatic free fatty acid levels, oxidative, endoplasmic reticulum and cytokine-mediated stress

influencing the balance and effects of profibrotic, pro-inflammatory and antifibrotic, anti-inflammatory adipokines released from adipose tissue.10

Treatments directed at components of the metabolic syndrotitlee

Obesity

Obesity is a rational target for NAFLD therapy since weight loss should reduce many of the putative mediators of liver injury.

Diet-induced weight loss. Several small, largely uncontrolled studies have shown an improvement in either ALT or steatosis following diet-induced weight loss (with or without exercise).

There is less evidence that necroinflammation or fibrosis can be improved by weight loss alone. A recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) compared 48 weeks intensive lifestyle intervention (a combination of diet, exercise and behaviour modification) with structured education. There was a significantly greater weight loss and improved NASH histological activity score (NAS) in the lifestyle intervention group.11 This study also showed that patients who achieved greater than 7% weight loss had significantly greater improvements in all three components of the NAS score (steatosis, lobular inflammation, ballooning injury) compared with those who lost less than 7%. Therefore, at present, aiming for a weight loss of 7% through diet and exercise appears to be a reasonable target in overweight and mildly obese patients.8

Surgery. Various surgical procedures are currently in use for the treatment of obesity. Biliopancreatic diversion appears to carry a significant risk of liver failure and worsening fibrosis and should therefore be avoided in patients with NAFLD. More encouraging results have been reported for gastric bypass and gastric banding surgery, all studies thus far reporting improvements in metabolic parameters and steatosis, with some, but not all, showing an improvement in necroinflammation and fibrosis.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance

Evidence that insulin resistance may contribute to both inflammation and fibrosis in NAFLD has led to several pilot studies of metformin and glitazones in patients with NAFLD. Most encouraging results have been reported for the glitazone class of drugs that act as agonists for the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-g. Five RCTs of glitazones have been reported, all showing an improvement in ALT and steatosis and most an improvement in liver cell injury and inflammation.8 Thus far, no study has shown a convincing benefit on fibrosis. In the largest RCT to date, pioglitazone significantly improved each individual aspect of liver injury, but failed to achieve the study end-point of a two-point improvement in NAS score with no worsening of fibrosis more often than placebo.12

Dyslipidaemia

Hypertriglyceridaemia affects 20–80% of patients with NAFLD. There are sound scientific reasons to support the use of fibrates (the conventional triglyceride-lowering agents) in patients with NAFLD. To date, the only controlled study in patients with histological follow-up reported no effect on liver biochemistry or histology after one year of clofibrate.

There is less rationale for using statins to treat NAFLD, but they can be safely prescribed for ‘conventional’ indications, including T2DM and high cardiovascular risk, since there is no evidence that patients with pre-existing NAFLD are at increased risk of statin-induced idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity.13

Hypertension

No RCTs have specifically examined the effect of different antihypertensive agents on the liver in hypertensive patients with NAFLD. A growing body of evidence suggests that therapy directed at the renin-angiotensin system maybe beneficial for the liver. As yet, only one pilot study has examined the use of angiotensin-2 receptor blockade in patients with NASH; this showed a reduction in serum markers of fibrosis.14

Treatments directed at the livtitler

An increased understanding of the mechanisms of progressive liver damage in NAFLD has stimulated the search for therapies specifically targeting the liver, rather than individual components of the metabolic syndrome that may have beneficial effects. The role of oxidative stress in disease pathogenesis has prompted several studies of antioxidants.15 Most recently, a large multicentre RCT reported that vitamin E (800 IU/day) improved all histological lesions of NAFLD except fibrosis, and patients on vitamin E had a two-point improvement in NAS score significantly more often than those on placebo.12 Vitamin E has also been shown to improve NASH features when given in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA).16 The only large, placebo-controlled RCT of UDCA alone in patients with NASH showed no benefit after two years of treatment.

Liver transplantatititlen

Patients with NAFLD who progress to decompensated cirrhosis or develop HCC are candidates for liver transplantation. Perhaps unsurprisingly, steatosis recurs in most patients within four years, with 50% developing NASH and fibrosis. Cases of recurrent cirrhosis are also reported.17,18 Risk factors for recurrence are:

the presence of insulin resistance or T2DM pre- and post-transplantation

weight gain following transplantation

a high cumulative steroid dose.

These findings highlight the importance of ensuring weight and metabolic control in reducing the risk of disease recurrence in a group of patients who will undoubtedly contribute increasing numbers to transplant programmes in the future.

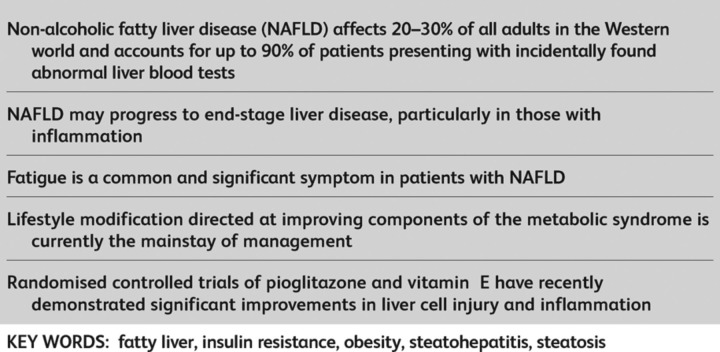

Key points.

References

- 1.Machado M, Marques-Vidal P, Cortez-Pinto H. Hepatic histology in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. J Hepatol. 2006;45:600–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1212–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argo CK, Northup PG, Al-Osaimi AM, Caldwell SH. Systematic review of risk factors for fibrosis progression in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2009;51:371–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanyal AJ, Banas C, Sargeant C, et al. Similarities and differences in outcomes of cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatitis. C. Hepatology. 2006;43:682–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.21103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology. 2006;44:865–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.21327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:134–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0912063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newton JL, Jones DE, Henderson E, et al. Fatigue in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is significant and associates with inactivity and excessive daytime sleepiness but not with liver disease severity or insulin resistance. Gut. 2008;57:807–13. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.139303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratziu V, Bellentani S, Cortez-Pinto H, Day CP, Marchesini G. A position statement on NAFLD/NASH based on the EASL 2009 Special Conference. J Hepatol. 2010;53:372–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldstein AE, Wieckowska A, Lopez AR, et al. Cytokeratin-18 fragment levels as noninvasive biomarkers for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicenter validation study. Hepatology. 2009;50:1072–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.23050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day CP. From fat to inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:207–10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:121–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.23276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, et al. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1675–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Browning JD. Statins and hepatic steatosis: perspectives from the Dallas Heart Study. Hepatology. 2006;44:466–71. doi: 10.1002/hep.21248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokohama S, Yoneda M, Haneda M, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of an angiotensin II receptor antagonist in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2004;40:1222–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mark N, de Alwis W, Day CP. Current and future therapeutic strategies in NAFLD. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:1958–62. doi: 10.2174/138161210791208901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dufour JF, Oneta CM, Gonvers JJ, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of ursodeoxycholic acid with vitamin E in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1537–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Contos MJ, Cales W, Sterling RK, et al. Development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease after orthotopic liver transplantation for cryptogenic cirrhosis. Liver Transplant. 2001;7:363–73. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.23011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ong J, Younossi ZM, Reddy V, et al. Cryptogenic cirrhosis and posttransplantation nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:797–801. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.24644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]