Abstract

Background

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are functionally and structurally essential for tumor progression. There are 3 main origins of CAFs: mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), epithelial-to-mesenchymal (EMT) transition cells, and tissue-resident cells. Pericytes retain characteristics of progenitor cells and can differentiate into other cells under normal physiological conditions and into myofibroblasts under pathological conditions. Exosomes play an important role in intercellular communication by transferring membrane components and nucleic acids between different cells. In this study, we evaluated whether cancer cell-derived exosomes are involved in regulating the transition of pericytes to CAFs.

Material/Methods

Exosomes from GES-1 and SGC7901 cells were isolated by serial centrifugation and purified from the supernatant by the 30% sucrose/D2O cushion method. A transmission electron microscope was used to observe exosome morphologies, and nanoparticle tracking analysis was used to analyze size distribution of exosomes. Western blot analysis, immunofluorescent staining, and qPCR were employed to detect CAFs marker expression and signaling pathways involved in CAFs transition.

Results

Gastric cancer cell-derived exosomes enhanced pericytes proliferation and migration and induced the expression of CAFs marker in pericytes. We then demonstrated that the PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK pathways were activated by tumor-derived exosomes, and BMP pathway inhibition reverses cancer exosomes-induced CAFs transition.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that gastric cancer cells induce the transition of pericytes to CAFs by exosomes-mediated BMP transfer and PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK pathway activation, and suggest that pericytes may be an important source of CAFs.

MeSH Keywords: Exosomes, Pericytes, Tumor Microenvironment

Background

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common cancers and is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. The incidence of GC varies widely across different countries. More than 70% of GC cases occur in Asia, and half of them occur in China [2]. Although the incidence of GC has decreased in most parts of the world due to improvement in surgical techniques, GC morbidity remains high in Asia.

Multiple cellular components make up the tumor microenvironment, such as malignant cells, inflammatory cells, stromal fibroblasts, various progenitor cells, endothelial cells, and perivascular cells [3–5]. Among them, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are important components of tumors like gastric cancer (GC) [6]. CAFs regulate multiple cellular functions, including extracellular matrix deposition, angiogenesis, metabolism reprogramming, and chemoresistance [7,8], thus playing key roles in determination of malignant progression of cancer growth, vascularization, and metastasis [9]. Fibroblast-activating protein (FAP) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) secreted by CAFs can create a niche for cancer cells and promote their motility [10]. Indeed, tumor cells can induce CAFs to undergo a differentiation process and develop invasive and migratory abilities. However, the mechanism of the interaction between CAFs and gastric cancer cells is still not clear. CAFs are blast-like, spindle-shaped cells that have been reported to originate from different cells through a variety of mechanisms, and the main sources of CAFs are mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [11,12], epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [11], and resident tissue fibroblasts [13]. Pericytes are known as mural cells that are associated with healthy or pathological vasculatures [14], and are believed to play a possible role in preventing tumor cell invasion and metastasis via inhibition of excessive sprouting, stabilization of the nascent vasculature, protection of the capillaries from regression and rarefaction, and remodeling of the primitive vasculatures to mature ones [15]. A number of studies showed that pericytes have characteristics of progenitor cells and possess the potential to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, and skeletal muscle cells [14,16–18]. In addition, pericytes can also differentiate into myofibroblasts under pathological conditions, which contributes to renal fibrosis, hepatic fibrosis, and chronic lung diseases [19–21].

Exosomes are pleomorphic vesicles-like bodies, secreted by various cell types and originated from the late endosomes (or multivesicular endosomes) of the cellular endocytic system, with diameters mostly between 30 and 150 nm. Under an electron microscope, exosomes are flat, spherical, or goblet bodies wrapped by phospholipid bilayers. In the body fluid, exosomes are mainly spherical, and can be collected by sucrose density gradient solutions in the density range of 1.13–1.19 g/ml. The origin of exosomes can be reflected by their particular compositions, and they play an important role in intercellular communication by transferring membrane components and nucleic acids between different cells. The exosomes released by tumor cells contain large amounts of oncogenic molecules, including proteins and microRNA, which play an important role in tumor progression and metastasis. Studies have shown that exosomes play a pivotal role in tumor cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and the transduction and recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells into tumor cells. Moreover, it has been reported that the exosomes secreted by prostate cancer cells can induce the transduction of adipose stem cells derived from tumor cells. Breast cancer- and ovarian cancer-derived exosomes can also induce adipose tissues to be transformed into mesenchymal stem cells in order to obtain physical and functional expressions of CAFs. In addition, tumor cells can exhibit the mesenchymal-like phenotype by releasing exosomes that contain mesenchymal tissue factors during epithelial mesenchymal transition (epithelial-mesenchymal transition, EMT). These exosomes possess the procoagulant activity of endothelial cells; thus, they can affect the vascular properties of tumors. It was reported that the exosomes originated from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells can promote the colony formation of myelomas. The fact that tumor progression can be promoted by the reversion of stromal cells to CAFs mediated by malignant cells has encouraged the exploration of the mechanisms underlying this transition.

The roles of CAFs in tumor invasion and metastasis have attracted considerable attention in recent years; however, little attention has been paid to the pericytes-CAFs transition. The aim of the present study was to explore the role of GC-derived exosomes on pericytes-to-CAFs trans-differentiation and the signaling pathway involved in this process.

Material and Methods

Culture of gastric cancer cells

Human gastric epithelial cells (GES-1) and gastric cancer cells SGC7901 were purchased from Cell Bank, Type Culture Collection Committee (Chinese Academy of Sciences) and cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS.

Exosome isolation and purification

Exomes derived from SGC7901 and GES-1 were isolated and purified as described previously [2]. Briefly, the exosomes in fetal bovine were removed by centrifuging at 4°C for 16 h at 100 000 g and filtration through 0.2-μm syringe-fitted filters (Millipore). Then, the exosome-depleted fetal bovine serum was used for cell culture (DMEM supplemented with 10% exome-depleted fetal bovine serum). After cells grew to confluence, the culture medium was collected and centrifuged twice at 2000 g for 20 min to remove the cells and debris. The supernatants were then concentrated by ultrafiltration through 100-kDa MWCO hollow-fiber membranes (Millipore) at 1000 g for 30 min, and loaded into centrifuge tubes (Beckman) with the underlayer of 30% sucrose/D2O density cushion (5 ml) to form a visible interphase. The SW-32Ti swinging-bucket rotor (Optima L-90K, Beckman Coulter) was used to ultracentrifuge the tubes at 100 000 g and 4°C for 1 h. Then, the sucrose density cushions at the bottom of these tubes that contain exosomes were collected, while the non-banded fractions that contain nonmembrane protein complexes were also collected as the exosomes control (E-control). After washing 3 times through 100-kDa miniature hollow-fiber cartridges (Millipore) at 1000 g for 30 min, as described above, the exosomes and the nonmembrane proteins (E-control) were obtained. The exosomes were sterilized by 0.22-μm capsule filters (Millipore) and stored at −70°C. The BCA assay kit (Pierce) was used to measure protein concentrations.

Transmission electron microscope observation of exosome morphologies

We uniformly placed 20 μL of the purified exosomes solution on the copper mesh sample carrier with a diameter of 2 nm. After incubation for 1 min at room temperature, the exosomes solution was gently drawn away from the edge of the copper mesh with filter papers. We applied 3% (w/V) phosphotungstic acid solution (pH 6.8) to the copper mesh for negative staining for 5 min at room temperature. The copper mesh was dried under an incandescent light and placed in the sample chamber of the transmission electron microscope. The morphology of exosomes was observed and photographed. Twenty exosomes were randomly selected and their diameters were recorded using the scale ruler.

Exosome size and approximate concentration analysis by nanoparticle tracking analysis

The purified exosomes solution was diluted with ddH2O, and l-ml syringes were used to inject the samples into the test tank (being careful not to leave bubbles). We adjusted the dilution according to the number of particles recorded in NanoSight NS300 (Malvern, UK) so that 30–40 particles were observed in the visual field of the view screen. We waited for the machine to read automatically, then recorded and generated the reports.

Purification and cultivation of pericytes

The pericytes derived from human adipose tissues were isolated as previously described [22]. Briefly, about 10 mL of liposuction aspirates were centrifuged at low speed (1000 rmp for 3 min), and the upper yellow lipid section was separated and washed repeatedly with PBS. The blood vessels and white connective tissues were removed and the remaining lipid portion was sheared with scissors and washed repeatedly again with PBS. Then, 1 mg/mL of collagenase type II (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to digest the lipid tissues at 37°C for 30–40 min in a shaker at 250 rpm with the ratio of 1: 3 (tissue weight: collagenase volume), which was diluted in DMEM-F12 with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% non-essential amino acids (GIBCO), and 1% of antibiotics/antimycotics (GIBCO). The derived cell suspensions were filtered through a 70-μm strainer and incubated in blood lysis solution for 5–10 min, and then PBS was added at the ratio of 2: 1 before the cells were filtered again through a 40-μm strainer. The cells were then incubated with conjugated antibodies against CD-34 (Percp-Cy5.5), CD-45 (FITC), CD-56 (APC), and CD146 (PE) (BD Biosciences) and DAPI was added just prior to the analysis. All the DAPI-positive cells were excluded and the pericyte populations were confirmed to have at least 75% purity by FACS sorting. The CD146+/CD34−/CD45−/CD56− cells were sorted into a 24-well plate at the density of 20 000 cells/cm2 and cultured in EBM-2 complete medium (Lonza) until the first passage, and then further cultivated in DMEM F-12 medium with 20% FBS, 1% NEAA, and 1% antibiotics/antimycotics.

Exosomes labeling and internalization

SGC7901-derived exosomes and the E-control were labeled with CM-Dil according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen), and the exosomes from GES-1 cells were used as the cell control. Briefly, CM-Dil was diluted to the working fluid concentration (1.5 g/ml) and added into the exosomes at the final concentration of 1.5 μg/ml. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the 100-kDa MWCO ultrafiltration centrifuge tubes were used to collect the exosomes at 1000 g for 30 min. Pericytes were seeded into the 12-well plates (including pre-processed climbing tablets) at the density of l×104/well and incubated for 4 h at 37°C before collection.

Western blotting

Exosomes and cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (Millipore) supplemented with a complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 2 and 3 (Sigma-Aldrich). The protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay kit. The appropriate amount of protein lysates was loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to 0.2-μm PVDF membranes, and incubated with primary antibodies of CD9, CD81, CD63, FAP (Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-α-SMA (Santa Cruz), FSP, TSP-1 (DAKO), and Tn-C (1: 200 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), respectively. After incubation with the secondary anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies (Cell Signaling), the protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Immunofluorescent staining

Cells were seeded onto glass coverslips in 6-well plates or μ-slides (Ibidi, Germany). After they grew to the appropriate density, cells were washed 3 times with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min followed by permeabilization in 0.4% Triton X-100 and blocking in 5% BSA for 30 min. Primary antibodies were added and incubated for 1 h. Cells were then washed 5 times before incubation with secondary fluorescence coupled-antibody for 3 h. After multiple washes, DAPI was added at 1 μg/mL to counterstain the nuclei. Finally, images were acquired using a confocal laser scanning microscope.

Cell proliferation assay

Pericytes were seeded at a low density in 6-well plates and grew for 24 h. The culture medium was discarded and cells were washed 3 times with PBS before switching to serum-free medium. SGC7901-derived exosomes (GC Exos), E-control, and GES-1-derived exosomes were added at 50 μg/mL for different periods of time. Cell proliferation rates were determined by tetrazolium-based assay (CCK-8, Dojindo).

Wound-healing assay

To assess the cell migration, pericytes were cultured in 12-well plates with complete medium until 100% confluence. Then, the medium was switched to serum-free medium for 24 h after a wound was created by scratching the center of the wells. Cells were then washed 3 times with PBS and cultured in serum-free medium supplemented with or without exosomes. After 18 h, the wounds were observed under a microscope and images were taken. The migration scores were determined by the following criteria: 0 (no migration), 1 (migration initiated along the border but cells do not span the gap/void), 2 (migrating cells are spanning the gap/void but not completely populating the gap/void), and 3 (migrating cells have completely repopulated the gap/void). The average scores of replicates/groups were calculated and analyzed.

Transwell assay

Pericytes (8×104 cells in 200 μL) were suspended in serum-free medium and loaded into the upper chamber, while 500 μL of serum-free medium containing 800 mg/mL exosomes was loaded into the lower chamber of the Transwell plate (Corning). After culturing at 37°C for 6 h, the cells that grew on the upper membrane were wiped with a cotton swab while the cells that had migrated through the membrane and grew on the lower membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet. The stained cells on the lower membrane were observed under a microscope and at least 10 visual fields were analyzed for each group.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to extract total RNA. A spectrophotometer was used to measure the purity and quantity of RNA. Reverse transcription was performed to produce cDNA, and the reverse transcription reagent kit was from Promega (Madison, WI). The reverse transcription system consisted of 2 μg total RNA, 0.5 μg oligo-dT primer, 1 μl dNTP mixture, 2 μl RNase inhibitor, and 4 units of reverse transcriptase. The reverse transcription procedure was heating at 42°C for 60 min and inactivating reverse transcriptase at 95°C for 5 min followed by 4°C for 5 min. The real-time PCR system was 1 μL cDNA, 10 μl SYBR Green I (Roche Applied Science), (20 μmol/L) 0.5 μl forward primer, (20 μmol/L) 0.5 μl reverse primer, and 8 μl water-DEPC treatment. All RT-PCR amplification systems were the same. Amplification conditions were initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, template denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 57°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. GAPDH mRNA was regarded as the internal reference. The following expression formula was used: the expression level of the target gene=2–ΔΔCt. The primers are listed in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ±SEM. SPSS 13.0 software was used for statistical analysis. Means of the 2 groups were compared using the t test. The means of multiple groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. P<0.05 indicates significant difference.

Results

Exosomes identification and internalization

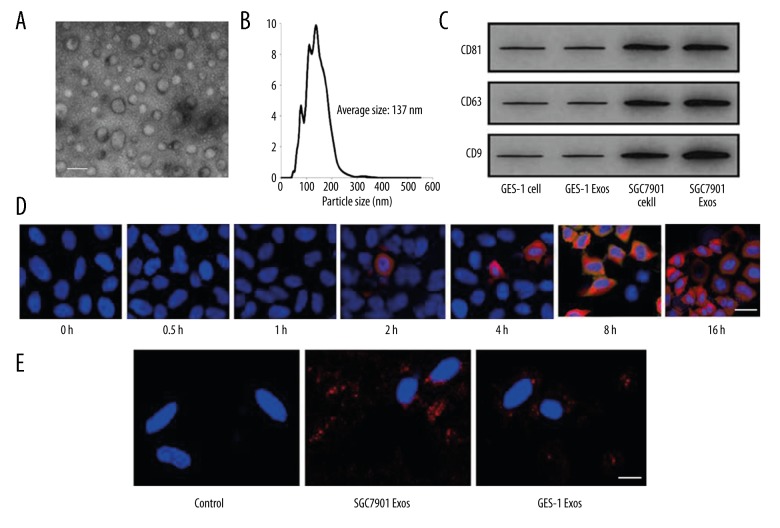

In this study, 3 different techniques (transmission electron microscopy, nanoparticles tracking analysis, and Western blot analysis) were used to identify exosomes. As shown in Figure 1A, exosomes developed a cup-shaped appearance with diameters ranging from 40 to 100 nm under transmission electron microscopy. For NTA, the size distribution was assessed, showing that the isolated exosomes had a predominant size of 70–200 nm (Figure 1B). Western blot analysis showed that tumor-derived exosomes had clearly higher levels of CD81, CD63, and CD9 compared to normal gastric epithelial cell-derived exosomes (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

GC cells secrete exosomes, which were rapidly internalized by pericytes in vitro. (A) The morphology of exosomes under TEM. Scale bar=100 nm. (B) Size distribution and concentration of exosomes analyzed by NTA. (C) Western blot analysis of exosomes-specific marker. (D) GC exosomes were internalized by pericytes; E-control served as control, bar=50 μm. (E) Pericytes were incubated with 50 mg/mL CM-Dil-labeled GC exosomes for the indicated times and were photographed using fluorescence confocal microscopy, bar=50 μm.

To investigate the internalization of exosomes by pericytes, exosomes were labeled with CM-Dil. As shown in Figure 1D, SGC7901 cell-derived exosomes internalized and accumulated in pericytes 1 h after application, and exosomes accumulated in pericytes over time. Compared with SGC7901 group, less GES-1-derived exosomes were taken up by pericytes (Figure 1E).

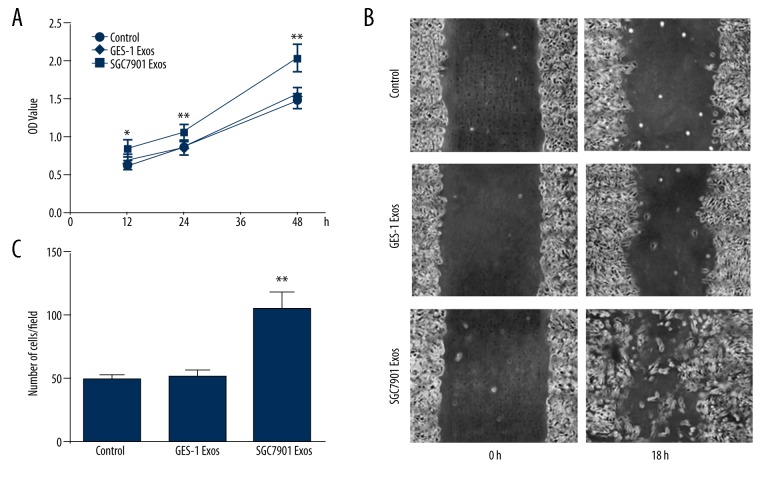

GC exosomes enhance pericytes proliferation

To investigate whether tumor-derived exosomes affect pericyte cell progression, pericytes were treated by SGC7901-derived exosomes at 50 μg/mL for 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h. Exosomes effectively induced proliferation in pericytes in a time-dependent manner (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Exosomes promote pericytes transition into CAFs with enhanced proliferation and migration in vitro. (A) Proliferation of pericytes induced by exosomes. Pericytes were treated with exosomes for 12, 24, and 48 h; E-control served as control. CCK-8 assays were performed in triplicate for each value. After 48 h, the number of pericytes represented by OD value was significantly higher than in those treated with control and GES-1 Exos, p<0.05. (B) Representative images of pericytes cultured in the wound-healing assay at 0 and 18 h exposed to GC exosomes compared to E-control (Control). (C) Migration scores were determined in pericytes exposed to exosomes. E-control served as control. Data represent mean ±SEM. ** P<0.01 vs. control group.

GC exosomes promote pericytes migration

To determine if the migratory ability of pericytes was affected by tumor exosomes, a wound-healing assay was performed (Figure 2B). The migration score was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Pericyte migratory ability was greatly enhanced by tumor-derived exosomes compared with GES-1-derived exosomes and control. Transwell assay was used to further confirm the pro-migratory effect of tumor-derived exosomes on pericytes (Figure 2C).

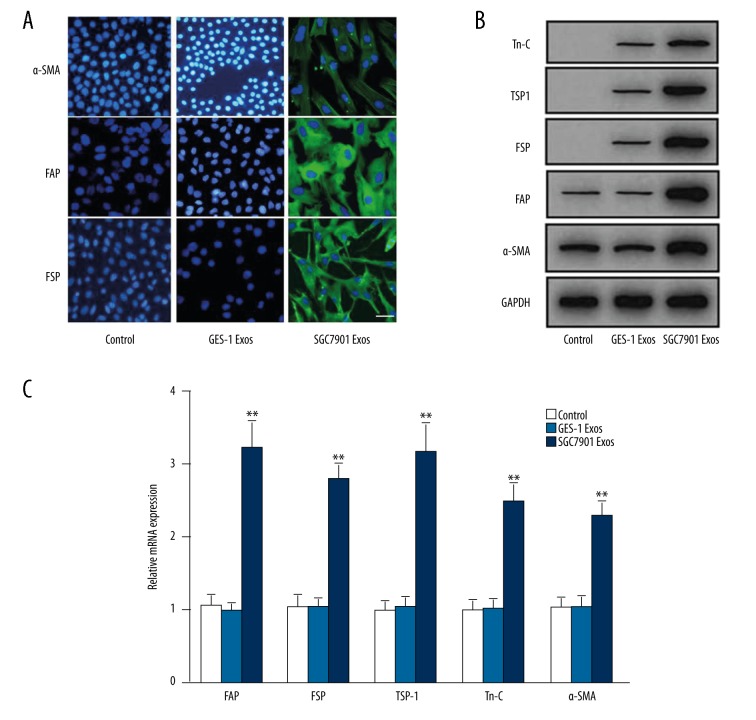

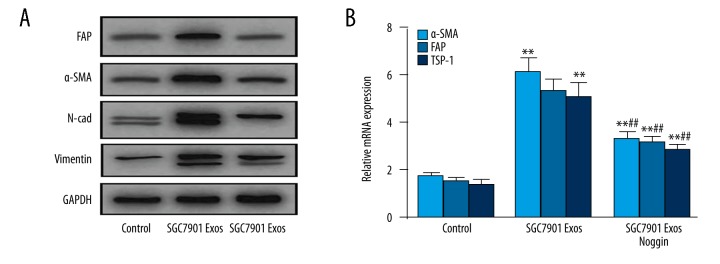

GC exosome promote pericytes transition to CAFs

We next identified the phenotypic changes induced by GC exosomes. Pericytes expressed low levels of α-SMA, but did not express FAP, FSP, TSP-1, or Tn-C. CAFs were defined as the evident expression of FAP, FSP, TSP-1, Tn-C, and α-SMA. As shown in Figure 3A, immunofluorescence data showed that GC exosomes but not GES-1-exosomes induced FAP and FSP expression and increased α-SMA expression. Western blot analysis also indicated that, compared to the GES-1 Exos group, GC exosomes treatment induced expression of FAP, FSP, TSP-1, and Tn-C protein levels (Figure 3B). This was verified at the protein level by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 3C). Collectively, these results indicate that pericytes undergo CAFs transition in response to tumor exosomes.

Figure 3.

Gastric cancer cell-derived exosomes induce pericytes-to-CAFs transition in vitro. Pericytes were treated with exosomes before immunofluorescence staining for α-SMA, FAP, and FSP, bar=50 μm (A), Western blotting for α-SMA, FAP, FSP, TSP-1, and Tn-C (B) and qPCR (C). GAPDH served as internal reference in B and C. Data represent mean ±SEM. ** P<0.01 vs. control group.

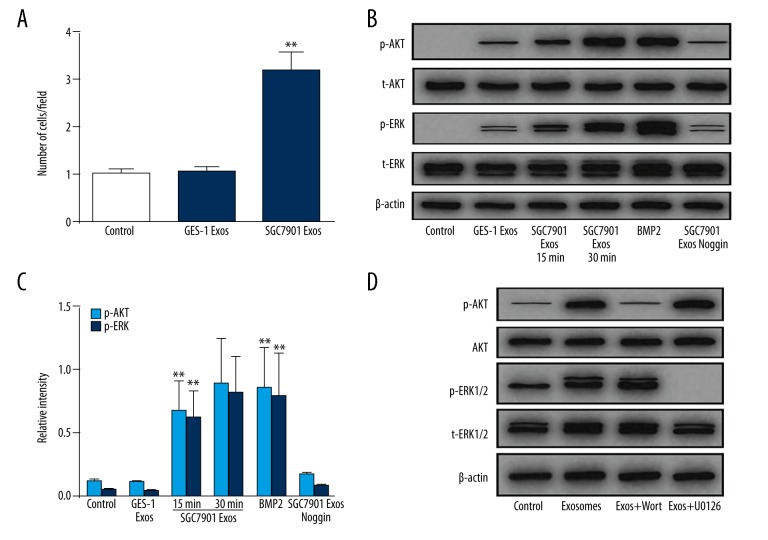

PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK pathways were activated by tumor-derived exosomes

The TGFβ superfamily has been proved to be critical for CAFs transition [23], within which bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) can induce differentiation, growth arrest, apoptosis, and many other distinct responses [24]. We investigated whether the BMP pathway was responsible for pericytes-to-CAFs transition induced by GC exosomes. We first demonstrated the mRNA level of BMP2 in GC exosomes (Figure 4A). Compared with normal cell-derived exosomes (GES-1 Exos), GC-derived exosomes showed higher levels of BMP2 expression. To investigate whether transition of pericytes to CAFs is associated with the BMP signaling pathway, we examined signaling pathways involved in CAFs transition.

Figure 4.

GC-derived exosomes induce AKT and ERK phosphorylation in pericytes. (A) qPCR analyses of BMP2 expression in SGC7901- and GES-1 derived exosomes. (B) Pericytes were pretreated with Noggin (1 μg/ml) for 30 min followed by treating SGC7901-derived exosomes (50 μg/mL) for different periods of time as indicated. The levels of p-AKT, t-AKT, p-ERK, and t-ERK were analyzed by Western blotting. BMP2 served as a positive control. (C) Indicated relative intensity of Western blot data of B. (D) Pericytes were preincubated for 30 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (Wort, 100 nM) or MEK inhibitor U0126 (10 mM) before culturing for 5 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 50 μg/mL GC exosomes. Expression of AKT and ERK1/2 and their active forms (p-AKT and p-ERK1/2) were analyzed by Western blot. GAPDH was used as internal reference. Data represent mean ±SEM. ** P<0.01 vs. control group.

There was an increase in the phosphorylation of RAC-alpha serine/threonine protein kinase (AKT) as well as the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 in the pericytes by 1 h after exosome treatment (Figure 4B, 4C). To verify that the increased phosphorylation of AKT and ERK specifically resulted from BMP signaling triggered by GC exosomes, the BMPs antagonist (Noggin) was used to block the BMP signaling pathway before the levels of phosphorylated AKT and ERK were detected. As shown in Figure 4B and 4C, Noggin reversed the increased phosphorylation of AKT and ERK following tumor exosomes treatment. Moreover, short-term treatment (5 min) with exosomes in the presence of AKT/ERK pathway inhibitors showed that the phosphorylation of kinases was the result of the induction of protein phosphorylation rather than the transformation of phosphorylated proteins (Figure 4D). Taken together, these results indicate that tumor exosomes specifically activate the AKT and ERK signaling pathways in pericytes.

BMP pathway inhibition reverses tumor exosomes-induced CAFs transition

To determine whether the BMP signaling pathway is responsible for the pericytes-to-CAFs transition triggered by tumor exosomes, we blocked the BMP pathway with BMPs antagonists Noggin, followed by exosomes treatment. As shown in Figure 5A, treatment with Noggin (1 μg/ml) strongly reversed the tumor exosomes-induced pericyte-fibroblast transition and decreased the expression of CAF markers, including FAP, FSP, TSP-1, Tn-C, and α-SMA in pericytes, which was verified at the mRNA level (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

BMP inhibition attenuates GC derived exosomes-induced transition of pericytes to CAFs. Pericytes were treated with GC exosomes (50 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of Noggin (1 μg/ml) for 1 h. The levels of p-AKT and p-ERK were examined by Western blotting (A) and qPCR (B). Data represent mean ±SEM. ** P<0.01 vs. control group, ## P<0.01 vs. SGC7901 Exos group.

Discussion

CAFs play an important role in the process of tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. In the tumor matrix, CAFs are very important cells that act as the primary cells producing ECM and determining the tumor kinetics [25]. The molecular and functional phenotypes of NAFs differ from those of CAFs, which are characterized by the expression of FAP, FSP, and alpha-SMA. In many tumor matrices, CAFs appear to possess the characteristic of promoting fibroblast proliferation. CAFs also produce a series of growth factors and proteolytic enzymes that promote tumor growth and invasion. The protective and supporting effects of CAFs on tumor cells have become the targets of anti-tumor therapies. CAFs originate from cells via many different mechanisms. While the typical source of CAFs is the local mesenchyme, bone marrow is believed to be another potential source of CAFs because it has been observed that CAFs originate from mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells. In addition, it was also reported that CAFs can originate from endothelial cells [26], pericytes [27], and fat cells [28]. In the present study, we focused on an important subject related to the origin of CAFs in the tumor microenvironment. We identified a novel mechanism by which pericytes serve as a reservoir for tumor stromal fibroblasts and the pericyte-fibroblast transition is controlled by tumor-derived exosomes. We found that: (1) GC-derived exosomes rapidly entered into pericytes; and (2) in response to their interaction with GC exosomes, pericytes acquire a CAFs phenotype with enhances proliferative and migratory properties and evident expression of FAP, FSP, TSP-1, Tn-C, and α-SMA in vitro, suggesting that GC exosomes induce the phenotypic conversion from pericytes to CAFs.

Kinase activation in signaling pathways is very important for tumors to promote the activation of CAFs, which includes PDGF receptors as well as TGFβ and downstream signaling. Webber et al. found that exosomes deliver TGFβ and promote the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, which indicates that tumor exosomes can mediate stromal cell differentiations [29]. Some previous studies have confirmed that tumor cell-derived exosomes express TGFβ, which possess the biological activity of activating the Smad-dependent signal pathways, which is also an important condition for stem cell self-renewal and differentiation.

This dynamic of TGFβ in tumor progression has led us to investigate BMP roles, which also belongs to TGFβ and plays vital roles in tumor progression. Recently, it was found that fibroblasts derived from mouse prostate tumors stimulated by BMPs can increase angiogenesis via the upregulation of the chemokine SDF1α/CXCL12, and BMP not only played a role in cancer cells, but also affected CAFs [30]. One of the effects was that over-expression of Noggin in CAFs decreased CAF cell proliferation [31]. Once uptake of GC exosomes occurs, cell signaling pathways are activated, and gene expression is altered in target cells. Our data showed that BMP2 was expressed by GC-derived exosomes, and this BMP activated the PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK signaling pathway and induced CAFs transition, and the BMP signaling pathway inhibitor Noggin blocked the phosphorylation of AKT and ERK, thereby inhibiting the PI3K/AKT and MAPK signaling pathway and reversing the tumor exosomes-induced pericyte-fibroblast transition and decreasing the expression of CAF markers.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that gastric cancer cells induced the transition of pericytes to CAFs by exosomes-mediated BMP transfer and PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK pathway activation. Pericytes may be an important source of CAFs. Our findings elucidate a new mechanism by which tumor cells induce pericytes to differentiate into tumor-associated fibroblasts, and the exosomes are important mediators in this process. Further studies should focus on the interactions between exosomes and pericytes, which may optimize the current therapeutic strategies for GC.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, et al. Gastric cancer: Descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarker Prev. 2014;23:700–13. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan Y, Wang LF, Wang RF. Role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9717–26. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i33.9717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tlsty TD, Hein PW. Know thy neighbor: Stromal cells can contribute oncogenic signals. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:54–59. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casey SC, Vaccari M, Al-Mulla F, et al. The effect of environmental chemicals on the tumor microenvironment. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36(Suppl 1):S160–83. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan Y, Wang LF, Wang RF. Role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9717–26. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i33.9717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: Functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:309–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cirri P, Chiarugi P. Cancer associated fibroblasts: The dark side of the coin. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:482–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erez N, Truitt M, Olson P, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts are activated in incipient neoplasia to orchestrate tumor-promoting inflammation in an NF-kappaB-dependent manner. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:135–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu J, Qian H, Shen L, et al. Gastric cancer exosomes trigger differentiation of umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells to carcinoma-associated fibroblasts through TGF-beta/Smad pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udagawa T, Puder M, Wood M, et al. Analysis of tumor-associated stromal cells using SCID GFP transgenic mice: Contribution of local and bone marrow-derived host cells. Faseb J. 2006;20:95–102. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3669com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jodele S, Chantrain CF, Blavier L, et al. The contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to the tumor vasculature in neuroblastoma is matrix metalloproteinase-9 dependent. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3200–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koyama H, Kobayashi N, Harada M, et al. Significance of tumor-associated stroma in promotion of intratumoral lymphangiogenesis: Pivotal role of a hyaluronan-rich tumor microenvironment. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:179–93. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armulik A, Genove G, Betsholtz C. Pericytes: Developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell. 2011;21:193–215. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosaka K, Yang Y, Seki T, et al. Pericyte-fibroblast transition promotes tumor growth and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E5618–27. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608384113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collett G, Wood A, Alexander MY, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinase Axl modulates the osteogenic differentiation of pericytes. Circ Res. 2003;92:1123–29. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000074881.56564.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dellavalle A, Sampaolesi M, Tonlorenzi R, et al. Pericytes of human skeletal muscle are myogenic precursors distinct from satellite cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:255–67. doi: 10.1038/ncb1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrington-Rock C, Crofts NJ, Doherty MJ, et al. Chondrogenic and adipogenic potential of microvascular pericytes. Circulation. 2004;110:2226–32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144457.55518.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin SL, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA, et al. Pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts are the primary source of collagen-producing cells in obstructive fibrosis of the kidney. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1617–27. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mederacke I, Hsu CC, Troeger JS, et al. Fate tracing reveals hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors to liver fibrosis independent of its aetiology. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2823. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel MS, Taylor GP, Bharya S, et al. Abnormal pericyte recruitment as a cause for pulmonary hypertension in Adams-Oliver syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2004;129A:294–99. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valadares MC, Gomes JP, Castello G, et al. Human adipose tissue derived pericytes increase life span in Utrn (tm1Ked) Dmd (mdx)/J mice. Stem Cell Rev. 2014;10:830–40. doi: 10.1007/s12015-014-9537-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webber J, Steadman R, Mason MD, et al. Cancer exosomes trigger fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9621–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owens P, Polikowsky H, Pickup MW, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins stimulate mammary fibroblasts to promote mammary carcinoma cell invasion. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Micke P, Ostman A. Exploring the tumour environment: Cancer-associated fibroblasts as targets in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2005;9:1217–33. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.6.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeisberg EM, Potenta S, Xie L, et al. Discovery of endothelial to mesenchymal transition as a source for carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10123–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugimoto H, Mundel TM, Kieran MW, et al. Identification of fibroblast heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1640–46. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jotzu C, Alt E, Welte G, et al. Adipose tissue derived stem cells differentiate into carcinoma-associated fibroblast-like cells under the influence of tumor derived factors. Cell Oncol. 2011;34:55–67. doi: 10.1007/s13402-011-0012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishra L, Derynck R, Mishra B. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in stem cells and cancer. Science. 2005;310:68–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1118389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang S, Pham LK, Liao CP, et al. A novel bone morphogenetic protein signaling in heterotypic cell interactions in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:198–205. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pham LK, Liang M, Adisetiyo HA, et al. Contextual effect of repression of bone morphogenetic protein activity in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:861–74. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]