ABSTRACT

Dengue virus (DV) infection can cause either a self-limiting flu-like disease or a threatening hemorrhage that may evolve to shock and death. A variety of cell types, such as dendritic cells, monocytes, and B cells, can be infected by DV. However, despite the role of T lymphocytes in the control of DV replication, there remains a paucity of information on possible DV-T cell interactions during the disease course. In the present study, we have demonstrated that primary human naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are permissive for DV infection. Importantly, both T cell subtypes support viral replication and secrete viable virus particles. DV infection triggers the activation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, but preactivation of T cells reduces the susceptibility of T cells to DV infection. Interestingly, the cytotoxicity-inducing protein granzyme A is highly secreted by human CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells after exposure to DV in vitro. Additionally, using annexin V and polycaspase assays, we have demonstrated that T lymphocytes, in contrast to monocytes, are resistant to DV-induced apoptosis. Strikingly, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were found to be infected with DV in acutely infected dengue patients. Together, these results show that T cells are permissive for DV infection in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that this cell population may be a viral reservoir during the acute phase of the disease.

IMPORTANCE Infection by dengue virus (DV) causes a flu-like disease that can evolve to severe hemorrhaging and death. T lymphocytes are important cells that regulate antibody secretion by B cells and trigger the death of infected cells. However, little is known about the direct interaction between DV and T lymphocytes. Here, we show that T lymphocytes from healthy donors are susceptible to infection by DV, leading to cell activation. Additionally, T cells seem to be resistant to DV-induced apoptosis, suggesting a potential role as a viral reservoir in humans. Finally, we show that both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes from acutely infected DV patients are infected by DV. Our results raise new questions about DV pathogenesis and vaccine development.

KEYWORDS: dengue virus, replication, T lymphocytes

INTRODUCTION

Dengue virus (DV) is the most prevalent arthropod-borne virus in the tropical and subtropical areas of the world. Infection by any of the four serologically related DVs (serotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4 [DV1 to DV4]) causes a wide range of clinical presentations, from a flu-like disease to severe hemorrhaging that can evolve to shock and death (1). In addition to viral factors, the pathogenesis of DV infection involves both innate and adaptive immune responses (reviewed in references 2–4). Human cells, such as monocytes, dendritic cells (DCs), and B cells, have been implicated in resistance to DV infection. However, DV infection of these cells in vitro induces the secretion of inflammatory mediators, apoptosis, and polyclonal B cell activation, which contribute to vascular leakage and DV-induced disease (5–8).

In addition to the above-mentioned cells, T lymphocytes are a major population activated during dengue fever (9, 10). Previous reports have indicated that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells play a role in the control of DV infection, mostly due to T cell-dependent cytotoxicity against virus-infected cells (11, 12). In support of this concept, CD8+ T cell activation and proliferation are inversely correlated with dengue viremia and appear to occur late in the course of DV infection (13). In contrast, low-affinity anti-DV T cells, induced during secondary heterotypic infection, contribute to the high viral load and intense inflammatory cytokine secretion observed in severe dengue cases (14). Moreover, activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have previously been found to be associated with hemorrhagic disease (10, 13, 15). This suggests that while T cells may contribute to controlling DV replication, they could also be involved in the pathogenesis of the disease (3, 16). It is possible that DV directly infects human T cells and affects their functions. It has been shown that human T leukemia cells and T cell lines can be infected by DV serotype 2 in vitro (17, 18) and in humanized mice (19), suggesting a possible interaction between this flavivirus and human T cells. However, using flow cytometry, two reports have demonstrated that human T cells are not infected by DV in vitro (20) or ex vivo (21). Nevertheless, whether DV directly interacts with primary human T cells and the possible consequences of these interactions during DV infection remain largely unknown.

To gain insight into possible DV-T cell interactions, we used a series of virology- and immunology-based assays with primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells exposed to DV serotypes 1 to 4. We observed that naive primary human T lymphocytes (CD4+ and CD8+) are permissive for DV infection and support viral replication, as well as the synthesis of infectious virus particles. Additionally, after infection by DV, T lymphocytes became activated and CD4+, but not CD8+, T cells secreted granzyme A (GzmA). Despite being infected by DV, T lymphocytes were resistant to DV-induced apoptosis. Additionally, using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from acutely infected dengue patients, we confirmed the susceptibility of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to DV. Together, our observations reveal a novel DV-host interaction that could contribute to the understanding of dengue pathogenesis.

RESULTS

DV infects and replicates in CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes through interaction with the heparan sulfate moiety.

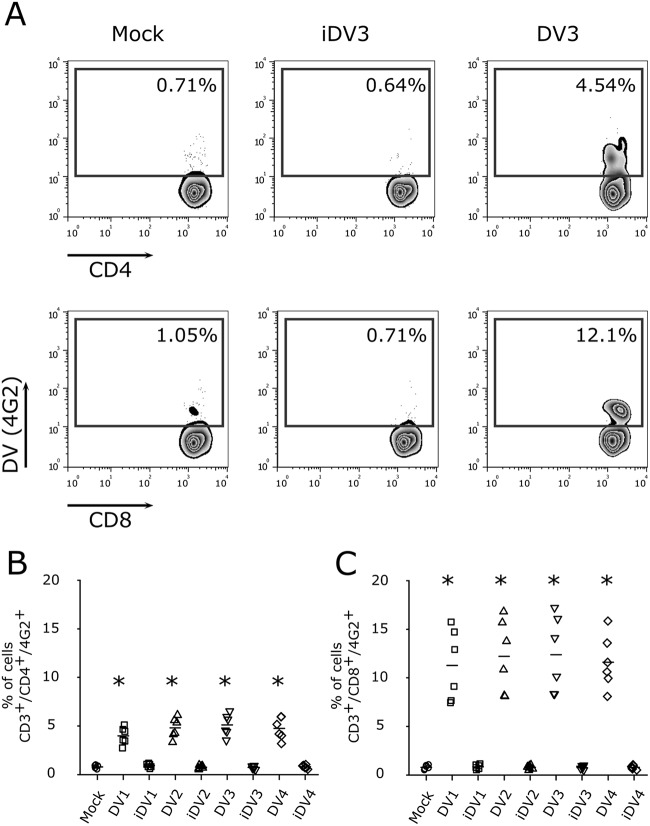

Because dengue fever patients have previously been shown to display enhanced T cell activation (10, 13, 15), we first asked whether DV directly interacts with T lymphocytes. For this assessment, we infected PBMCs with different multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of DV3 and observed that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are susceptible to dengue virus infection (Fig. 1). In addition, kinetic experiments using PBMCs from healthy donors confirmed the infection of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes by DV3 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Thus, PBMCs from healthy donors were exposed to the four DV serotypes (MOI of 10) and, after 5 days postinfection, virus infection was measured by means of intracellular staining of the virus envelope protein through flow cytometry (22). As previously shown (7, 23, 24), B lymphocytes (CD19+) and monocytes (CD14+) were infected by DV serotypes 1 to 4 (Fig. S2A, D, and E). Similarly, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were found to be infected by the four DV serotypes (Fig. S2A to C). Furthermore, when purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations from 6 healthy donors (Fig. S2G and H) were infected with DV, similar results were observed (Fig. 2A to E). It is noteworthy that confocal microscopy of purified T cell populations exposed to DV confirmed that CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were infected by DV (Fig. 2D and E). All DV serotypes presented similar levels of infectivity in T cells (Fig. 2B and C).

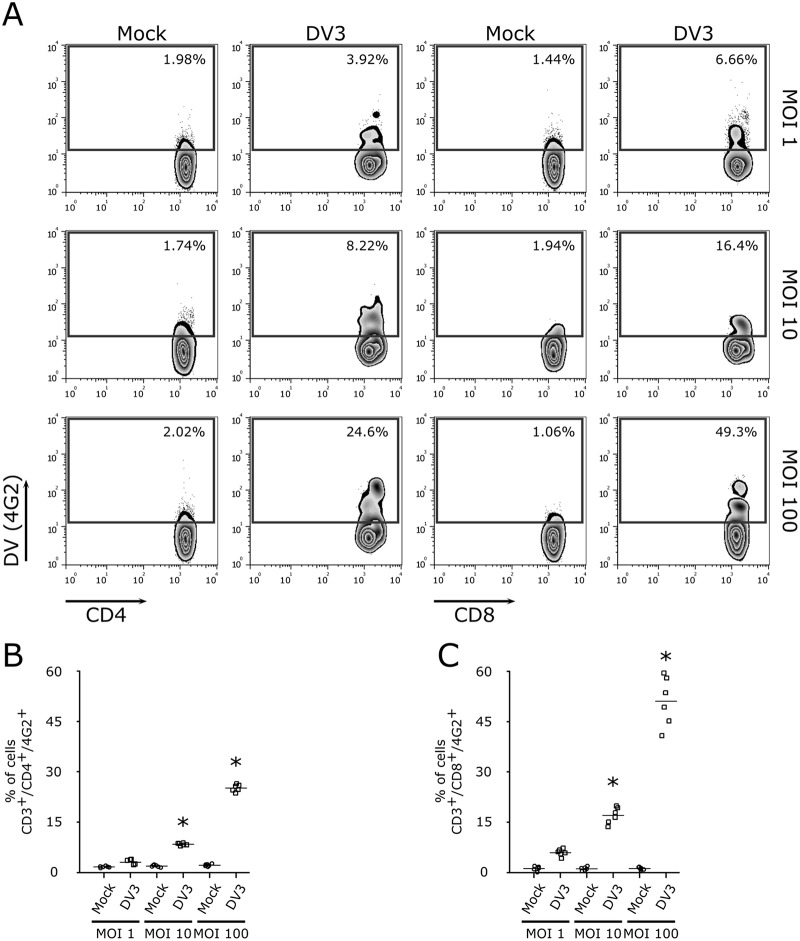

FIG 1.

Infection of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes with different MOIs of DV3. (A) Representative flow cytometry density plot data showing the results for mock infection and infection of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes (4G2+) with DV3 (strain 98) at MOIs of 1, 10, and 100, 5 days postinfection. (B and C) Bars represent the average frequencies of mock infection (circles) and DV3 infection (squares) of CD4+ (B) and CD8+ (C) T cells (six different healthy donors). *, P ≤ 0.05 compared to the results for mock-infected controls.

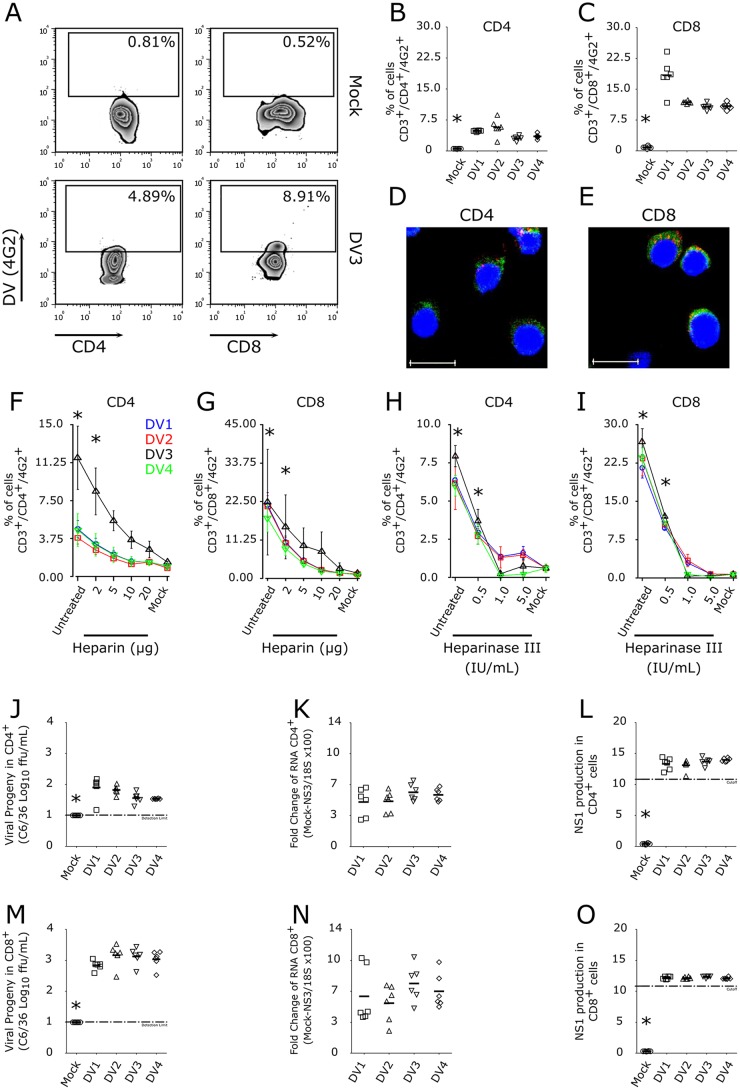

FIG 2.

Human lymphocytes are susceptible to DV infection and replication. (A) Representative flow cytometry density plots of purified cells showing the frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells infected by DV. The number within each box refers to the frequency of cells within each gate. (B and C) Average frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infection by the four DV serotypes. Mock infection (circles) and DV1 BR90 (squares), DV2 265 (triangles), DV3 98 (inverted triangles), and DV4 360 (diamonds) infection. Bars show the mean values for samples from six healthy donors. *, P ≤ 0.05 compared to the results for infection by four DV serotypes. (D and E) Confocal fluorescence microscopy of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells labeled for DNA (DAPI; blue), DV (anti-E protein MAb; red), and immunophenotyping markers (anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 MAb; green). Scale bar = 10 μm. (A, D, E) Data are representative of six independent experiments. (F and G) Flow cytometry data indicating the average frequencies of DV-infected CD4+ (F) and CD8+ (G) T lymphocytes (CD14+-depleted cells from six healthy donors) after virus treatment with different concentrations of heparin (2 to 20 μg). (H and I) Average frequencies, using a flow cytometry assay, of CD4+ (H) and CD8+ (I) T lymphocytes infected with DV1 to DV4 after cell treatment with different concentrations of heparinase III (0.5 to 5.0 IU) and infection with the four DV serotypes. Data represent the mean values ± standard errors of the means (SEM) for cells from six healthy donors. *, P ≤ 0.05 compared to the results for mock-infected controls. (J and M) DV progeny in cell culture supernatants from purified CD4+ (J) and CD8+ (M) T lymphocytes infected with the four DV serotypes were quantified using a focus-forming assay in C6/36 cells. (K and N) DV replication on CD4+ (K) and CD8+ (N) T lymphocytes (purified via cell sorting) was determined by real-time PCR assay. Quantification of DV nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) gene mRNA, normalized to the housekeeping gene 18S, for comparison of the levels in infected cells and mock-infected cells. (L and O) Qualitative determination of the levels of DV nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) in cell culture supernatants of purified CD4+ (L) and CD8+ (O) T lymphocytes infected by DV by using a capture ELISA from PanBio (values >11 indicate NS1 secretion). Mock infected (circles) and DV1 BR90 (squares), DV2 265 (triangles), DV3 98 (inverted triangles), and DV4 360 (diamonds) infected. Bars show the mean values for cells from six healthy donors. *, P ≤ 0.05 compared to the results for infection by four DV serotypes.

Next, to gain insight into the possible host-expressed molecules involved in DV binding in T cells, we examined the heparan sulfate (HS) moiety, which has been characterized as a mediator of DV binding and entry in several cell lines (25–27). Preexposure of DV to heparin, an inhibitor of host HS-virus interactions, led to decreased virus infectivity in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2F and G). Similarly, treatment of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with heparinase III, an HS-cleaving enzyme, reduced DV infectivity (Fig. 2H and I). These results suggest that HS moieties participate in DV binding to human T cells.

We next investigated whether T cells support DV replication. Using a focus-forming assay (Fig. 2J and M), reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) for the NS3 gene in infected cells (Fig. 2K and N), and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of the secretion of NS1 into the cell culture supernatant (Fig. 2L and O), we observed that purified CD4+ or CD8+ human T lymphocytes support active replication of DV. Moreover, the staining of PBMCs infected by DV using an additional in-house-made monoclonal antibody (MAb) against NS3 [1722-1B; IgG1(κ)] suggested that DV replicates in CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 3). Together, these results indicate that human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are susceptible to infection with DV serotypes 1 to 4 and support virus replication. Additionally, when PBMCs from 16 healthy donors were exposed to DV1 to DV4 in vitro, CD8+ T cells were found to be more susceptible to DV infection than CD4+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 4). In contrast, no staining was detected when cells were exposed to gamma-irradiated DV1 to DV4 (Fig. 5).

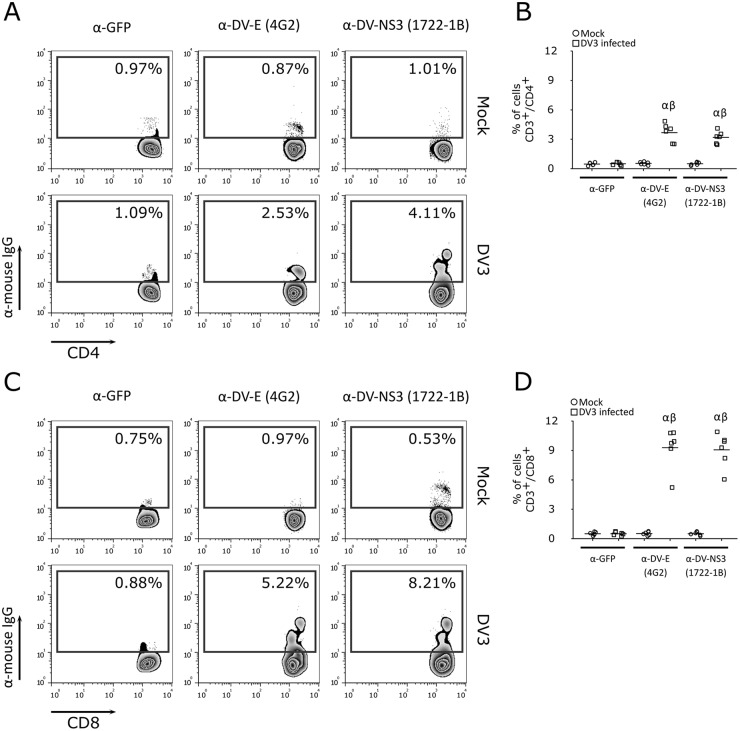

FIG 3.

Detection of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte infection using anti-E and anti-NS3 MAbs. Representative flow cytometry density plot data showing CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (C) T lymphocyte infection with DV3 (strain 98) and mock infection after 5 days postinfection, using anti-GFP (isotype control), anti-E (4G2), and anti-NS3 (1722-1B) antibodies. (B and D) Bars represent the average frequencies of CD4+ (B) and CD8+ (D) T cell (samples from six healthy donors) infection with DV3 (squares) and mock infection (circles) after staining with anti-GFP (isotype control), anti-E (4G2), and anti-NS3 (1722-1B) antibodies. α, P ≤ 0.05 comparing mock infection to DV3 infection using the same antibody; β, P ≤ 0.05 comparing staining with 4G2 and 1722-1B to the results for the isotype control.

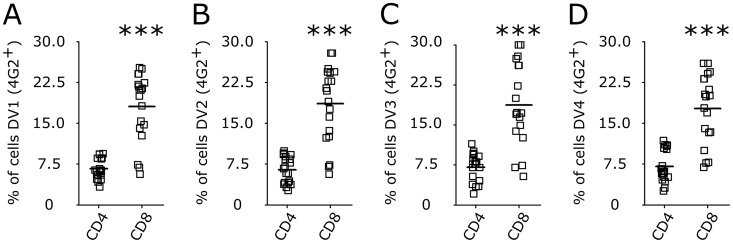

FIG 4.

Differential susceptibilities of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes to DV infection. Bars represent the average frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes infected by DV1 (A), DV2 (B), DV3 (C), and DV4 (D) at an MOI of 10. After 5 days, cells were recovered and stained for phenotyping markers (CD3, CD4, and CD8) and for dengue virus E protein (4G2 antibody). Data are from 24 PBMC samples (representing 16 different healthy donors) infected with four DV serotypes. ***, P ≤ 0.001 comparing the levels of infection of CD8+ to that of CD4+ T lymphocytes.

FIG 5.

Inactivated DV does not infect human T cells. (A) Representative flow cytometry density plot data showing human CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte infection (MOI of 10) with DV3 98 and gamma-irradiated DV3 98 (iDV3) and mock infection. The number within each box refers to the frequency of cells within each gate. (B and C) Average percentages of CD4+ (B) and CD8+ (C) T cells infected with four DV serotypes and the respective gamma-irradiated strains in PBMC cultures after 5 days postinfection. Mock infection (circles) and infection with DV1 BR90 or inactivated DV1 BR90 (squares), DV2 265 or inactivated DV2 265 (triangles), DV3 98 or inactivated DV3 98 (inverted triangles), and DV4 360 or inactivated DV4 360 (diamond). Bars represent the mean values ± SEM for cells from six healthy donors. *, P ≤ 0.05 compared to the results for mock controls and for inactivated DV.

DV infection activates resting T cells, which secrete granzyme A but do not undergo apoptosis.

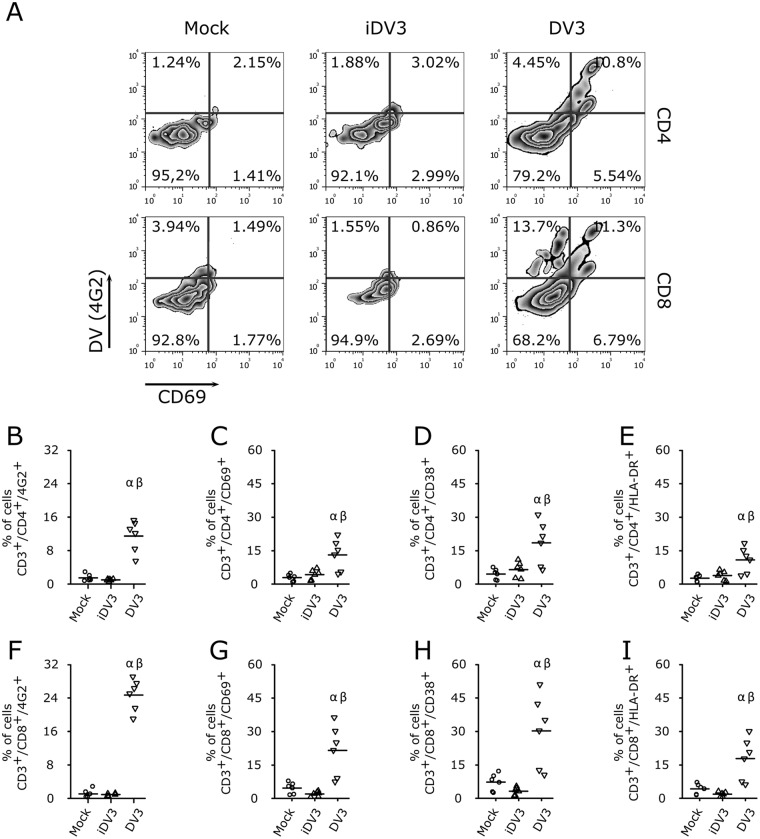

It has been previously shown that T cells are activated by means of CD69 expression during severe dengue fever in children (10). To test whether T lymphocytes are directly activated by DV infection, PBMCs were exposed to DV serotype 3 for 5 days and stained for the expression of the activation markers CD69, CD38, and HLA-DR. DV3 infection increased the frequencies of CD69+, CD38+, and HLA-DR+ expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6) in infected and noninfected cells. Similar results were observed when cell cultures were exposed to different DV serotypes (Fig. S3). Also, not all infected T cells expressed activation markers (Fig. 6; Fig. S3).

FIG 6.

DV infection activates T lymphocytes. (A) Representative flow cytometry density plot data showing DV3 infection (4G2+) and cellular activation (CD69+) of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. (B to I) Average frequencies of CD4+ (B) and CD8+ (F) T cell infection with DV3 and levels of expression of activation markers CD69+ (C and G), CD38+ (D and H), and HLA-DR+ (E and I) in CD4+ (B to E) and CD8+ (F to I) T lymphocytes. PBMC samples from six healthy donors were mock infected (circles) or infected with gamma-irradiated DV3 98 (iDV3; triangles) and DV3 98 (inverted triangles). α, P ≤ 0.05 comparing the results for mock and DV3 infection; β, P ≤ 0.05 comparing the results for iDV3 and DV3 infection.

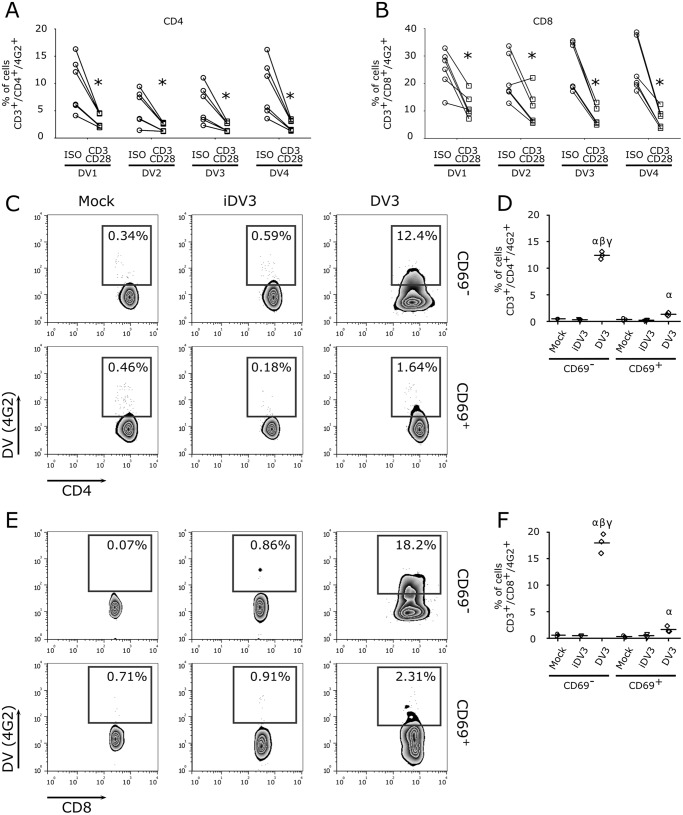

We next asked whether the activation status of T lymphocytes could modulate viral infectivity. Indeed, stimulation of enriched lymphocyte cultures upon polyclonal stimulation (anti-CD3/anti-CD28 MAb) impaired DV infection in both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 7A and B). Thus, infection of purified CD69+ and CD69− cells confirmed that the later CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were more susceptible to DV infection than CD69+ T cells (Fig. 7C to F).

FIG 7.

Activated T lymphocytes are more resistant to DV infection. (A and B) Enriched T lymphocyte cultures (CD14+ depleted) were stimulated overnight with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 MAbs and infected with the four DV serotypes. After 5 days, cells were stained for anti-DV MAb (4G2+) and cellular markers (CD3+/CD4+ and CD3+/CD8+). Data show levels of T cell infection after stimulation with anti-GFP MAb (isotype control; circles) and anti-CD3/anti-CD28 MAb (squares). *, P ≤ 0.05 compared to the results for nonactivated lymphocytes. (C to F) PBMCs were stimulated using anti-CD3/anti-CD28 MAbs, and activated (CD69+) and naive (CD69−) T cells were purified by flow cytometry and infected with DV3 98 (MOI of 10) for 5 days. (C and E) Representative flow cytometry density plot data showing DV3 98 infection (4G2+) in purified CD69+ (activated) and CD69− (nonactivated or naive) T cells. (D and F) Average frequencies of CD4+ (D) and CD8+ (F) T cell infection with DV3 in activated (CD69+) and naive (CD69−) T cells. Mock (circles), gamma-irradiated DV3 98 (iDV3) (inverted triangles), and DV3 98 (diamonds) infected. α, P ≤ 0.05 comparing the results for mock and DV3 infection; β, P ≤ 0.05 comparing the results for iDV3 and DV3 infection; γ, P ≤ 0.05 comparing the results for infection of CD69− and CD69+ cells.

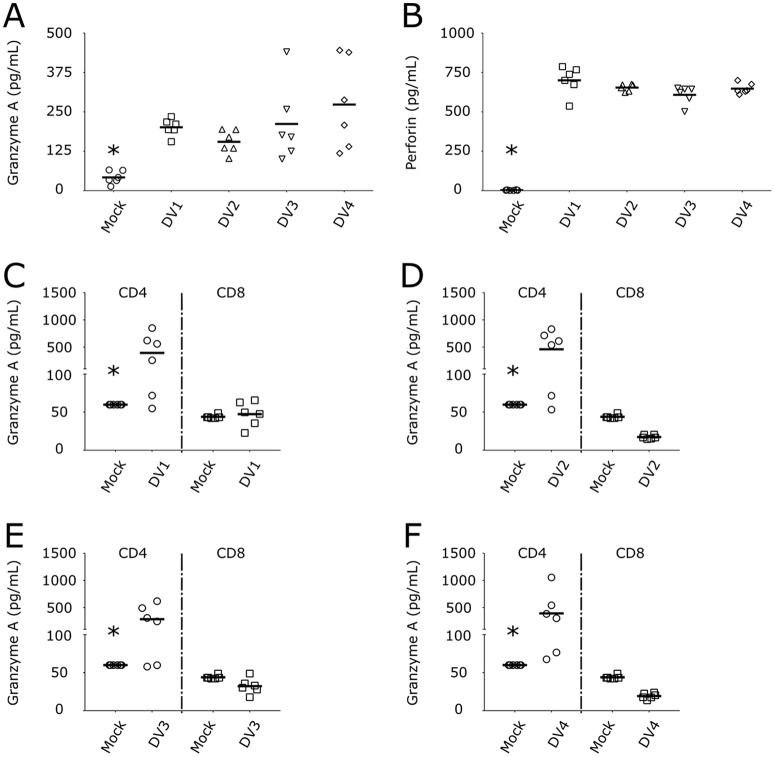

It was also described that T cell activation led to the release of granzyme serine proteases and the pore-forming protein perforin (28), thus triggering the apoptosis of target cells. GzmA (Fig. 8A) and perforin (Fig. 8B) were secreted by DV-infected PBMCs. Next, we infected purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to determine the sources of GzmA and perforin. Interestingly, CD4+ T lymphocytes were the main source of GzmA secretion after DV infection (Fig. 8C to F), whereas neither CD4+ nor CD8+ T cells were the source of human perforin (Fig. S4).

FIG 8.

DV infection of CD4+ T lymphocytes triggers the secretion of granzyme A. (A and B) Concentrations of granzyme A (A) and perforin (B) in PBMCs infected with four DV serotypes. Mock infected (circles) and DV1 BR90 (squares), DV2 265 (triangles), DV3 98 (inverted triangles), and DV4 360 (diamonds) infected. *, P ≤ 0.05 compared to the results for infection by the four DV serotypes. (C to F) Purified CD4+ (circles) and CD8+ T cells (squares) were infected with DV1 (C), DV2 (D), DV3 (E), and DV4 (F), and granzyme A was measured in the cell culture supernatants after 5 days. Bars show the mean values for cells from six healthy donors infected with strains of the four DV serotypes. *, P ≤ 0.05 compared to the results for infection by DV.

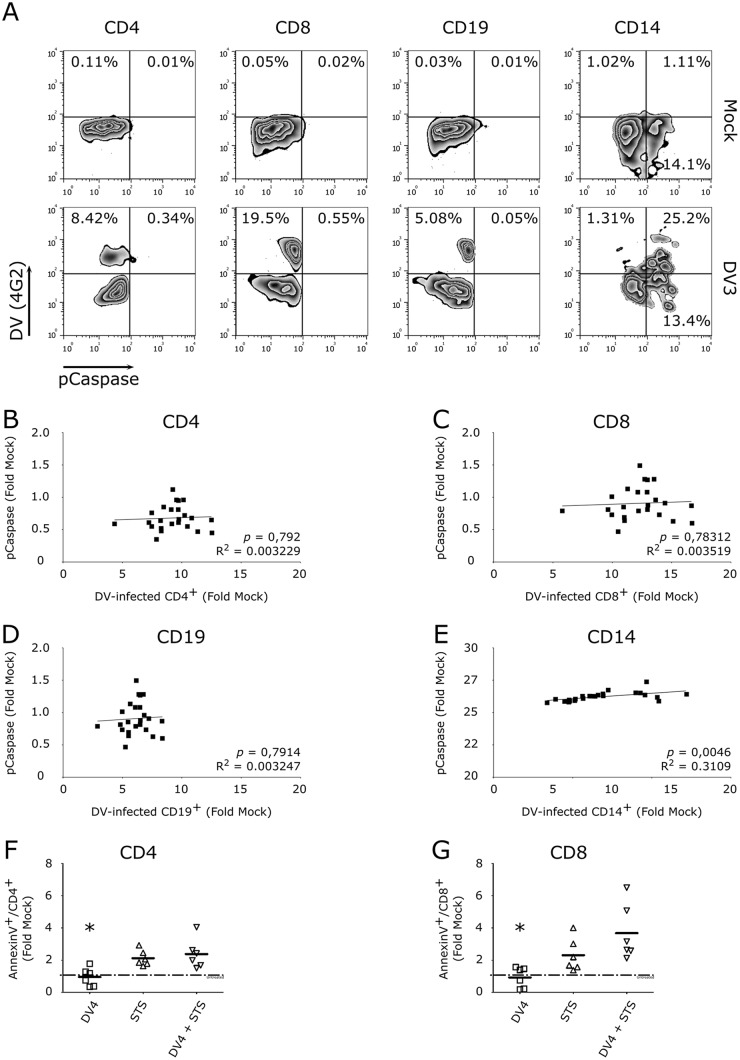

DV infection triggers apoptosis in a wide range of cells, including dendritic cells, neurons, and hepatocytes (22, 29). We next asked if DV could also trigger T cell apoptosis. Programmed cell death in DV-exposed PBMC cultures was examined by polycaspase staining and flow cytometry. In contrast to monocytes and dendritic cells (22), CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes did not undergo apoptosis following DV infection (Fig. 9A). Further analyses confirmed the lack of correlation between infection and apoptosis in T cells (and in CD19+ B cells), as well as the expected positive correlation in CD14+ monocytes (Fig. 9B to E). Similar results were obtained when annexin V–7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) staining was used to quantify DV-induced apoptosis in T cells (Fig. S5A to D). Together, these data suggest that upon infection, resting T cells are activated by DV but do not undergo apoptosis, an important process that controls viral replication (8). Additionally, because DV-exposed T cells appeared to be more resistant to apoptosis than DV-infected monocytes, we asked whether DV actively inhibits the apoptosis of T lymphocytes. To do so, PBMC cultures were infected with DV4 and, 4 days later, exposed to low doses of the apoptosis inducer staurosporine (STS) (30). The results showed that DV failed to prevent STS-induced annexin V expression by human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 9F and G). These results suggest that DV does not actively inhibit STS-induced apoptosis in human T lymphocytes.

FIG 9.

DV infection does not modulate lymphocyte apoptosis. (A) Representative flow cytometry density plot data for PBMCs infected with DV3 98 (4G2+) and polycaspase stained. (B to E) Pearson correlation analysis between the percentages of infected CD4+ T cells (B), CD8+ T cells (C), and B cells, i.e., CD19+ (D) or CD14+ (E) monocytes, and polycaspase staining. The data represent fold induction of infection and apoptosis related to the results for the mock-infected control. PBMCs from six healthy donors were infected with four DV serotypes. (F and G) PBMCs from healthy donors were infected with DV4 360 for 4 days and treated with staurosporine (STS) for an additional 24 h. Average frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell apoptosis after staurosporine treatment (200 nM) in DV-infected cells and uninfected controls. Bars show the mean values for PBMCs from six healthy donors infected with DV4 360. The dotted-and-dashed lines (untreated) indicate the level of apoptosis of mock-treated control lymphocytes. *, P ≤ 0.05 comparing the results for DV4 infection to the results for STS treatment or STS treatment plus DV4 infection by one-way ANOVA.

CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes are infected with DV in patients in the acute phase.

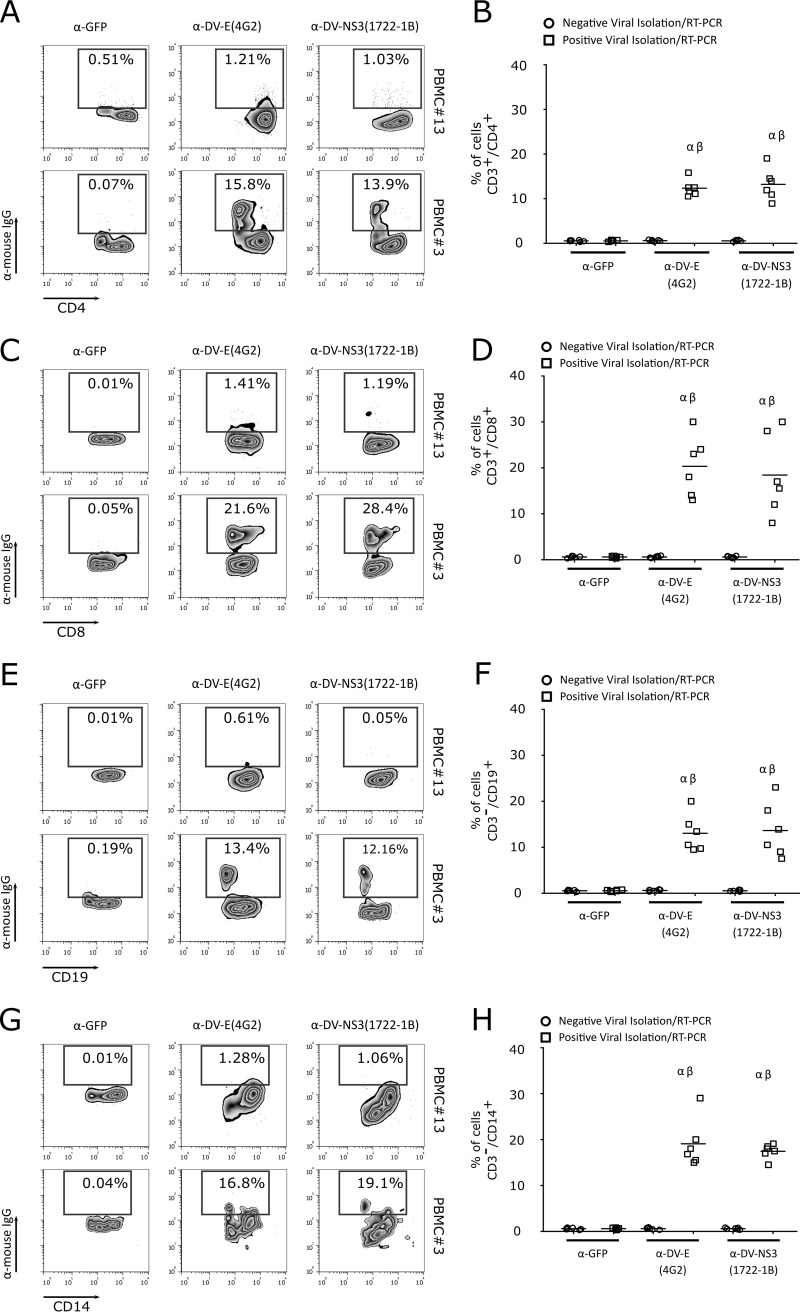

Although the results described above indicated that DV serotypes 1 to 4 directly interact with and replicate in T cells in vitro, we asked whether these lymphocytes were also infected during dengue fever. Thus, we collected PBMCs and serum samples from 13 patients with clinical signs of dengue fever in an area where DV is endemic. Serum samples were used for virus isolation in C6/36 cells, followed by RT-PCR confirmation. Six of the 13 patients were positive for DV. In the positive samples, viremia was measured by a focus-forming assay in C6/36 cells in focus-forming units per ml (FFUC6/36/ml), with values between 2.2 × 104 and 2.6 × 105. Table 1 summarizes the data from patient samples used in the assay. To determine whether CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from patients with dengue fever were infected with DV, PBMCs were stained with two different monoclonal antibodies, anti-DV E protein MAb (clone 4G2) or anti-DV NS3 protein MAb (clone 1722-1B). Flow-cytometric analysis showed that human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from acutely infected DV patients (positive for viral isolation and by RT-PCR) were positively stained with anti-DV E and DV NS3 MAbs (Fig. 10A to D). As previously demonstrated, monocytes (CD14+) and B cells (CD19+) were also infected by DV (Fig. 10E to H) (7, 8, 20). Together, these data suggest that during acute dengue fever, DV infects T cells.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characterization of human patient samples

| Sample | Gendera | Age (yr) | Virus isolation (IF)b | RT-PCR result | Viremia (FFUC6/36/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC#1 | F | 29 | Pos | DV1 | 3.9 × 104 |

| PBMC#3 | F | Pos | DV1 | 2.6 × 105 | |

| PBMC#4 | M | 23 | Pos | DV1 | 4.7 × 104 |

| PBMC#6 | M | 28 | Neg | Neg | ND |

| PBMC#7 | M | 53 | ND | DV1 | ND |

| PBMC#8 | M | 55 | Neg | Neg | ND |

| PBMC#11 | F | 36 | Neg | Neg | ND |

| PBMC#13 | F | 13 | Neg | Neg | ND |

| PBMC#14 | F | 25 | Neg | Neg | ND |

| PBMC#16 | M | 53 | Pos | DV1 | 2.2 × 104 |

| PBMC#18 | F | 38 | Pos | DV1 | 1.0 × 105 |

| PBMC#22 | M | 14 | Neg | Neg | ND |

| PBMC#27 | F | 51 | ND | Neg | ND |

M, male; F, female.

Pos, positive; Neg, negative; ND, not determined; IF, immunofluorescence.

FIG 10.

CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes are naturally infected by DV in acute-phase patients. (A, C, E, and G) Representative flow cytometry density data showing CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (C) T lymphocyte, B cell (CD19+) (E), and monocyte (CD14+) (G) infection by DV1 in PBMCs from an acute-phase patient. Lymphocyte infection was observed by labeling the viral proteins with anti-flavivirus E protein MAb (4G2), anti-DV NS3 MAb (1722-1B), or an isotype control (anti-GFP MAb). The number within each box refers to the frequency of cells within each gate. Phenotype staining was performed using anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD19, and anti-CD14 MAbs. Cell infection was shown using PBMCs from a patient negative for DV infection (PBMC#13) and a patient infected with DV1 (PBMC#3). (B, D, F, and H) Average frequencies of CD4+ (B) and CD8+ (D) T lymphocytes, B cells (F), and monocytes (H) infected by DV (anti-DV NS3 and anti-DV E MAbs) in PBMCs from seven negative (circles) and six DV-infected patients (squares). α, P ≤ 0.05 comparing the results for anti-DV MAb (4G2 or 1722-1B) staining in PBMCs from DV-infected and noninfected patients; β, P ≤ 0.05 comparing the results for staining with 4G2 or 1722-1B and the isotype control (anti-GFP MAb).

DISCUSSION

DV infects a wide range of cell types, including monocytes, dendritic cells, and B lymphocytes. The infection of those cells induces the activation and secretion of cytokines and antibodies, which can contribute to the immunopathogenesis of dengue (6–8, 20, 23, 24, 31). Despite the recognized role of T lymphocytes in the control of DV replication and also in the pathogenesis of hemorrhagic disease, there is controversy regarding the susceptibility of T cells to DV infection (11, 12, 15, 17, 24). In previous studies, T lymphocytes obtained from PBMCs or splenic mononuclear cells from healthy donors were not susceptible to DV2 infection (20, 24). In contrast, DV2 (strain 16681) was able to infect and replicate in T cell lineages (17, 18). Furthermore, human T cells were shown to be infected by DV2 (strain K0049) in a humanized mouse model (19), indicating a possible interaction between DV and T cells in vivo.

In the present study, using several immunology- and virology-based techniques, we found that the four DV serotypes can infect and replicate in primary human T lymphocytes. However, despite using cell sorting to purify cultures of T lymphocytes, we could not exclude the contribution of DV infection of monocytes/dendritic cells in the virus yield detected in the cell culture supernatant. Furthermore, we observed that HS moieties contribute to the binding of DV to T cells, as has been demonstrated previously for other cell lines (25, 32). Finally, using two different monoclonal antibodies against DV (anti-E protein and anti-NS3 protein MAbs), we demonstrated that both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are infected by DV in acute-phase patients, confirming the data obtained in in vitro experiments.

We have observed that DV infection triggers T cell activation and that activated cells become resistant to DV virus infection. It is well established that T lymphocytes are highly activated in dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) patients compared to their level of activation in patients with dengue fever, suggesting a role for T cell activation in the pathogenesis of DV hemorrhagic fever (10). Also, the activation and proliferation of CD8+ T cells seem to occur late in the course of DV infection and are inversely correlated with dengue viremia (13). In addition, T cell activation could impair their susceptibility to infection. For instance, resting T cells are susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1); nevertheless, virus integration is dependent on T cell activation (33). Furthermore, for myxoma virus, T cell activation is required to allow viral replication in T lymphocytes (34). Regarding DV infection, T lymphocyte activation could trigger the secretion of inflammatory mediators, leading to a cytokine storm (13, 15, 35). The serine proteases granzymes A, B, and K have been found at high levels in the plasma of DV-infected patients (36). Moreover, dengue-specific CD4+ T cells with cytolytic activity were recently shown to play a role in the control of DV infection in vivo (12). Here, we demonstrate that T cell activation triggered by DV infection leads to the secretion of the serine protease GzmA by CD4+ T cells. While DV-infected PBMCs release both granzyme A and perforin, we could not exclude the possibility that natural killer cells were the source of those mediators, especially perforin.

It has been previously demonstrated that DV infection triggers apoptosis in a number of cell types, such as hepatocytes and endothelial cells, contributing to the hepatic damage and hemorrhagic manifestations observed in severe dengue cases (29, 37, 38). DV also triggers the apoptosis of monocytes and dendritic cells, which impacts the immune response to the infection (8, 22, 39). Apoptosis has also been detected in leukocytes and microvascular endothelial cells in pulmonary and intestinal tissue, which could be associated with vascular plasma leakage (29). In contrast, we show here that CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were resistant to DV-induced apoptosis, which could suggest a viral escape mechanism. Extending cell survival allows viruses to replicate and mature (reviewed in reference 40). For instance, HIV, which infects CD4+ T cells, displays different strategies to avoid T cell apoptosis. As shown using Jurkat T cells, the HIV-1 protein Tat inhibits TRAIL-induced apoptosis (41), while HIV-1 Nef blocks Fas- and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-induced apoptosis (42). Additionally, T cells from hepatitis C virus HCV-/HIV-coinfected patients have been shown to be more resistant to apoptosis than T lymphocytes from HIV-infected patients (43). The same study demonstrated that HCV-infected CD4+ T cells are more resistant to HIV-induced cell death.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that human CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes are susceptible to DV infection in vitro, which triggers T cell activation and GzmA secretion by CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, T lymphocytes are resistant to DV-induced apoptosis. Additionally, once human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are infected in acute-phase patients, we hypothesize that T lymphocytes serve as viral reservoirs during DV infection, contributing to viremia and T cell activation. Finally, our study suggests an additional role for CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in DV pathogenesis that could influence vaccine development strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

Blood samples were obtained using a surface venipuncture procedure after DV-suspected or healthy donors provided written consent. In the case of children, parents provided written consent. All blood samples were blindly coded to ensure anonymity of the patients or healthy donors. Finally, the study protocol was approved by the Committee of Research Ethics from FIOCRUZ (CEP/FIOCRUZ) under the numbers 514/09 and CAAE: 49931415.7.1001.5248/Fiocruz.

Primary cell cultures.

Blood samples were collected from 33 clinically healthy adult donors (15 males and 18 females) with a mean age of 29.97 ± 4.21 years and no history of DV infection (IgM/IgG negative using an Alere enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) in the city of Curitiba (25°25′47″S, 49°16′19″W), Paraná State, South Brazil. Additionally, blood samples from patients with suspected DV infection (Table 1) were obtained in the city of Cambé (23°16′33″S, 51°16′40″W), Paraná State, South Brazil, where DV infection is endemic. From these samples, PBMCs were obtained by density gradient separation with lymphocyte separation medium (Lonza). Enriched lymphocyte cultures (CD14+ depleted) were purified by magnetic immunosorting (negative selection) with anti-CD14 Ab beads (Miltenyi Biotec) or from the non-plastic-adherent fraction of PBMCs. To perform the flow cytometry cell-sorting separation (FACSAria II; BD Biosciences), PBMCs were labeled with anti-CD3-phycoerythrin (PE) MAb (clone HIT3a), anti-CD14-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) MAb (clone M5E2), anti-CD8-peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP) MAb (clone SK1), anti-CD19-PE-Cy7 MAb (clone SJ25C1), and anti-CD4-allophycocyanin (APC) MAb (clone RPA-T4) (BD Biosciences) or their respective isotype controls. PBMCs, enriched lymphocytes (CD14+ depleted) or cultures purified by cell sorting were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza) containing 100 IU/ml penicillin (Gibco), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin B (Gibco), and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. The use of PBMCs, enriched lymphocytes (CD14+ depleted) or cell-purified T cells was defined based on the main objectives of each experiment and specified accordingly.

Viral stocks and infection of T lymphocytes.

DV infection assays were performed with all four serotypes. Two strains, DV1/BR/90 (GenBank accession number S64849.1), first described by Desprès and colleagues in 1993 (44), and DV4/TVP360, kindly provided by Ricardo Galler, Fiocruz/RJ, Brazil (GenBank accession number KU513442.1), were laboratory-adapted DV strains with a high number of passages in cell culture. Additionally, two DV strains that were recently isolated from acutely infected patients and maintained for 3 or 4 passages in C6/36 cells were also included in this study. DV2/ICC265 was isolated from a patient who acquired dengue fever in 2009 in the state of Paraná, Brazil. BR DV3/98-04 (GenBank accession number EF629368.1), first described by Nogueira and colleagues in 2008 (45), was isolated from a dengue fever patient in Rio Branco (9°58′29″S, 67°48′36″W), Acre, northern Brazil, in 2004. We refer to these strains herein as DV1 BR90, DV2 265, DV3 98, and DV4 360.

Viral stocks were obtained from clarified supernatant from larval Aedes albopictus (C6/36) cells infected with the different DV serotypes at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) between 0.1 and 1. The samples were stored at −80°C. The viral stock concentrations were obtained using a focus-forming-assay technique in the C6/36 cell line (46). A negative-control infection culture (mock) was conducted in parallel using noninfected C6/36 cell supernatant. Gamma-irradiated DV1 to DV4 were also used as controls in some experiments.

For DV infection, 5.0 × 105 human cells were incubated with viral stocks (MOI of 10) or gamma-irradiated virus or mock infected in RPMI without FBS for 2 h at 37°C. Later, the cultures were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 60 s. The supernatant was discarded, and the cells were recovered with 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 100 IU/ml penicillin (Gibco), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin B (Gibco), and 10% FBS. The cell suspensions were incubated for 5 days at 37°C under 5% CO2 in 24-well plates. The infected cells were recovered and used for further experiments.

Immunophenotyping and DV intracellular labeling.

For immunophenotypic and/or viral protein labeling, cell culture plates were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 60 s. The supernatants were stored at −80°C for further analysis, and the cells were recovered with 100 μl of blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] plus 5% FBS and 1% AB human serum [Lonza]) for 20 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the cells were recovered in 100 μl Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) and incubated for 20 min at room temperature, protected from light. After incubation, the cells were washed once with 100 μl of Perm/Wash solution (BD Biosciences), the plate was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 2 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were mixed with 100 μl of an anti-flavivirus E protein MAb (4G2 [ATCC HB-112]; 10 μg/ml) at 1:100 (vol/vol) in Perm/Wash or 100 μl of anti-DV nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) MAb (1722-1B; 10 μg/ml) at 1:100 (vol/vol) in Perm/Wash and incubated for 30 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. After incubation, the cells were washed with 100 μl Perm/Wash solution, mixed with 100 μl of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) at 1:100 (vol/vol) in Perm/Wash, and incubated for 30 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. Then, the cells were washed again with PBS and incubated with 50 μl of a MAb mixture diluted 1:50 (vol/vol) in PBS, including the following MAbs: anti-CD14-PE MAb (clone M5E2), anti-CD8-PerCP MAb (clone SK1), anti-CD19-PE-Cy7 MAb (clone SJ25C1), anti-CD4-APC MAb (clone RPA-T4), anti-CD3-APC-Cy7 MAb (clone SK7) (all from BD Biosciences), and their respective isotype controls. After incubation for 30 min at 37°C (5% CO2), the cells were washed and recovered with 200 μl of PBS. The cell suspensions were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACSCanto II instrument (BD Biosciences).

For confocal microscopy, one aliquot of labeled cells (as described above) was collected. The cells were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 2 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the cells were recovered in 50 μl of PBS containing 300 nM DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Molecular Probes) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS, added to a glass slide coated with 10% poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. After incubation, the cells were washed in PBS, the excess was removed by pipetting, a glass coverslip was added, and the edges were sealed. The images were analyzed using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems).

DV NS1 detection, focus-forming assay, and RT-qPCR.

The supernatants from PBMCs and purified cultures of T lymphocytes were analyzed for the presence of DV nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) using the Panbio dengue early ELISA (Alere) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction absorbance was read at wavelengths of 600 and 650 nm to calculate the index. Index values (PanBio units) were expressed according to the cutoff to determine the presence (>11 units) or absence (<9 units) of the NS1 protein in the culture supernatant.

Supernatants from cell cultures (PBMCs and purified T cells) were further used to quantitate the DV progeny using a focus-forming assay in C6/36 cells (FFUC6/36/ml), following the procedure adapted from Gould and Clegg (46). Finally, DV replication was measured in total RNA extracted from frozen/thawed purified T lymphocytes using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. RT-qPCR with the DV NS3 gene as a target was also performed. For RT-qPCR, cDNA was obtained using 5 μg of total RNA, random primers (4 pmol/reaction mixture; Invitrogen), and 1 μl of ImProm-II reverse transcriptase enzyme (Promega) for 2 h at 42°C. Quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.5 ng/μl of cDNA, and 4 pmol/reaction mixture of specific primers (Table 2). The cycling regimen was as follows: 50°C for 2 min and 96°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 96°C for 15 s, 59°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The constitutively expressed 18S gene was used for the normalization and quantification of the amplification reaction products. Gene expression was calculated by the cycle threshold (2−ΔΔCT) method adapted from Livak and Schmittgen (47).

TABLE 2.

Primer pairs used for qPCR assay of DV replication

| Gene target | Direction | Sequence | Fragment size (bp) | Tm (°C)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS3 | Forward | 5′-GACATCTTTCGAAAGAGAAG-3′ | 160 | 59 |

| Reverse | 5′-AGATACCAAACTCCAGCTAT-3′ | |||

| 18S | Forward | 5′-CACGGCCGGTACAGTGAAAC-3′ | 152 | 59 |

| Reverse | 5′-CCCGTCGGCATGTATTAGCT-3′ |

Tm, melting temperature.

DV binding to T lymphocytes.

Viral suspensions were incubated with heparin (Vacuplast). Briefly, an amount of 5.0 × 106 FFUC6/36 of a DV suspension of each of the four serotypes in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (L15; Thermo Fisher Scientific) (0.1 ml) was incubated with 2, 5, 10, or 20 μg/ml heparin or with PBS (positive control). After 2 h at 37°C, each DV-plus-heparin mixture was used as an inoculum for enriched lymphocyte cultures (CD14+ depleted) as described above in “Viral stocks and infection of T lymphocytes.”

Additionally, enriched lymphocyte cultures (CD14+ depleted) were treated with heparinase III (Sigma), an enzyme that removes heparan sulfate (HS) residues from the cell surface. For this purpose, an amount of 5.0 × 105 lymphocytes was treated with 0.5, 1.0, or 5.0 IU/ml heparinase III or with PBS (positive control) in 0.1 ml of RPMI medium at 37°C for 2 h. After cell treatment with heparinase III, the cells were washed with PBS and infected as described above in “Viral stocks and infection of T lymphocytes.”

Lymphocyte cell death triggered by DV infection.

After DV infection, lymphocyte cell death was analyzed using annexin V–7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) or the detection of activated caspases. PBMCs (from healthy donors) were infected (MOI of 10) with the four DV serotypes as described above in “Viral stocks and infection of T lymphocytes.” After 5 days, the cells were separated into two populations. The first group was analyzed for the percentage of infection as described above in “Immunophenotyping and DV intracellular labeling” and for activated caspases using the Image-iT live red polycaspase detection kit (Life Technologies). Briefly, 5.0 × 105 PBMCs were recovered, washed with 100 μl of 1× FLICA (fluorochrome inhibitor of caspases), and incubated for 60 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 protected from light. After incubation, 100 μl of binding buffer was added, and the analysis was performed using a FACSCanto II flow cytometer.

To confirm the data on activated caspases, the second group of cells was stained with the annexin V:PE apoptosis detection kit I (BD Biosciences) as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, for annexin V, 5.0 × 105 PBMCs were recovered, washed with 100 μl of binding buffer containing 5 μl of annexin V and 5 μl of 7-AAD, and incubated for 15 min at 37°C in 5% CO2, protected from light. After incubation, 100 μl of binding buffer was added, and the cells were analyzed on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer.

Additionally, 2 × 105 PBMCs from healthy donors were infected (MOI of 5) with DV4 360 (stock in C6/36 cells and titration in BHK-21 cells) and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Then, the cells were spun, the viral inoculum was removed, and the cells were suspended in supplemented RPMI 1640 medium. The cells were incubated for 4 days before being treated with staurosporine (200 mM; Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h and stained with anti-CD3-FITC MAb (clone UCHT1), anti-CD4-APC-Cy7 MAb (clone OKT4), anti-CD8-PE-Cy7 MAb (clone SK1; Biolegend), and anti-CD14-V450 MAb (clone MφP9; BD Biosciences). Next, the cells were incubated with annexin V-APC (Immunotools) for 15 min protected from the light. The PBMCs were then washed in annexin binding buffer, and propidium iodide (BD Pharmingen) was added prior to data acquisition on a FACSVerse (BD Biosciences).

Lymphocyte activation after DV infection.

To determine if lymphocyte infection by DV triggers the activation of these cells, PBMCs from clinically healthy donors (anti-DV IgM and IgG negative) were infected with DV for 5 days. After infection, lymphocyte activation was assessed by the expression of CD69 (anti-CD69-PerCP MAb; clone FN50), CD38 (anti-CD38-PE MAb; clone HB7), and HLA-DR (anti-HLA-DR-APC MAb; clone G46-6) (all antibodies from BD Biosciences). Additionally, DV infection of lymphocytes was measured using the 4G2 antibody together with the phenotypic markers anti-CD3-APC-H7 MAb (clone SK7), anti-CD4-AmCyan MAb (clone RPA-T4), and anti-CD8-PE-Cy7 MAb (clone SK1) (all antibodies from BD Biosciences). Labeling was performed as described above in “Immunophenotyping and DV intracellular labeling.”

Furthermore, to evaluate the permissiveness of activated lymphocytes to DV infection, enriched lymphocyte cultures (CD14+ depleted) were activated overnight using anti-CD28 MAb (clone CD28.2, 200 ng/well; BD Biosciences) and anti-CD3 MAb (clone HIT3a, 200 ng/well; BD Biosciences). As a control, enriched lymphocyte cultures were treated with an anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) monoclonal antibody (made in-house). After activation, the cells were washed and infected with DV (MOI of 10) as previously described. After 5 days, the cells were stained using anti-CD3-APC-Cy7 MAb (clone SK7), anti-CD4-APC MAb (clone RPA-T4), anti-CD8-PerCP MAb (clone SK1), anti-CD69-PE MAb (clone FN50) (all antibodies from BD Biosciences), and anti-DV MAb (4G2) as described above in “Immunophenotyping and DV intracellular labeling.”

Also, activated T cells (from PBMC cultures) were obtained using anti-CD3/anti-CD28 MAbs, as described above. After overnight incubation, the cells were stained using CD69-PE MAb (clone FN50; BD Biosciences), and the nonactivated (CD69−) and activated (CD69+) populations were purified using flow cytometry. Both populations were infected with DV3 (MOI of 10) or gamma-irradiated DV3 or mock infected for 5 days. After incubation, DV infection of lymphocytes was measured using 4G2 antibody together with the phenotypic markers anti-CD3-APC-Cy7 MAb (clone SK7), anti-CD4-APC MAb (clone RPA-T4), and anti-CD8-PerCP MAb (clone SK1) (phenotypic markers were from BD Biosciences). Labeling was performed as described above in “Immunophenotyping and DV intracellular labeling.”

Granzyme A and perforin detection.

The supernatants from PBMCs and purified cultures of T lymphocytes infected by DV were analyzed for the presence of granzyme A and perforin using the cytometric bead array human granzyme A flex set (BD Biosciences) and perforin human ELISA kit (Abcam), respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Permissiveness of T lymphocytes to DV infection in acute-phase DV patients.

To confirm the permissiveness of T lymphocytes to DV infection in acute-phase DV patients, blood samples from DV patients were analyzed. The samples were obtained from patients suspected to be infected by dengue virus (until 7 days after the beginning of the symptoms) based on clinical examination in the city of Cambé (23°16′33″S, 51°16′40″W), North Region of Paraná State, South Brazil. Blood and serum samples were collected with the patients' consent, as approved by the FIOCRUZ Research Ethics Committee (CAAE: 49931415.7.1001.5248). Serum samples were used to confirm the DV diagnosis by virus isolation in C6/36 cells, followed by one-step RT-PCR as previously described (48). For two patients (PBMC#27 and PBMC#7), we could not obtain serum, and dengue diagnosis was performed by one-step RT-PCR using RNA obtained (RNeasy minikit; Qiagen Hilden, Germany) directly from PBMCs (Table 1) (48).

PBMCs were obtained from blood samples as described above in “Primary cell cultures” and cryopreserved in 90% FBS and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The samples were thawed, washed in 1× PBS, and split into three aliquots for intracellular staining with mouse anti-flavivirus E protein MAb [4G2; IgG1/IgG2a(κ)], mouse anti-GFP MAb made in-house [isotype control; IgG1(κ)], and mouse anti-NS3 MAb [1722-1B; IgG1(κ)]. Additionally, PBMCs from DV-positive and DV-negative patients were stained using anti-CD3-PE MAb (clone HIT3a), anti-CD14-FITC MAb (clone M5E2), anti-CD8-PerCP MAb (clone SK1), anti-CD19-PE-Cy7 MAb (clone SJ25C1), or anti-CD4-APC MAb (clone RPA-T4) (all antibodies from BD Biosciences) to discriminate different cell populations, as stated above in “Immunophenotyping and DV intracellular labeling.”

Data analysis and statistics.

Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni posttest was used for statistical analysis unless otherwise stated in the figure legends. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Pearson correlation analysis was performed between DV infection and apoptosis. The analyses were performed with Prism software (version 5.0c; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). All data from flow cytometry and cell-sorting assays were analyzed in DIVA software version 6.0 (Becton Dickinson) and/or FlowJo version 7.1 (TreeStar, Inc.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Program for Technological Development in Tools for Health-PDTIS-FIOCRUZ for the use of its facilities (RPT07C, Microscopy Facility, and RPT08L, Flow Cytometry Facility, at the Carlos Chagas Institute/Fiocruz-PR, Brazil).

W.R.P. (grant number 309239/2015-0), L.R.V.A. (grant number 307408/2016-7), A.B. (grant number 304875/2014-7), and C.N.D.D.S. (grant number 309432/2015-4) received CNPq scholarships.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02181-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. 2009. Dengue guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pang T, Cardosa MJ, Guzman MG. 2007. Of cascades and perfect storms: the immunopathogenesis of dengue haemorrhagic fever-dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS). Immunol Cell Biol 85:43–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothman AL, Medin CL, Friberg H, Currier JR. 2014. Immunopathogenesis versus protection in dengue virus infections. Curr Trop Med Rep 1:13–20. doi: 10.1007/s40475-013-0009-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green AM, Beatty PR, Hadjilaou A, Harris E. 2014. Innate immunity to dengue virus infection and subversion of antiviral responses. J Mol Biol 426:1148–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurane I, Ennis FA. 1987. Induction of interferon alpha from human lymphocytes by autologous, dengue virus-infected monocytes. J Exp Med 166:999–1010. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libraty DH, Pichyangkul S, Ajariyakhajorn C, Endy TP, Ennis FA. 2001. Human dendritic cells are activated by dengue virus infection: enhancement by gamma interferon and implications for disease pathogenesis. J Virol 75:3501–3508. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3501-3508.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin YW, Wang KJ, Lei HY, Lin YS, Yeh TM, Liu HS, Liu CC, Chen SH. 2002. Virus replication and cytokine production in dengue virus-infected human B lymphocytes. J Virol 76:12242–12249. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12242-12249.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espina LM, Valero NJ, Hernandez JM, Mosquera JA. 2003. Increased apoptosis and expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha caused by infection of cultured human monocytes with dengue virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 68:48–53. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.68.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurane I, Brinton MA, Samson AL, Ennis FA. 1991. Dengue virus-specific, human CD4+ CD8− cytotoxic T-cell clones: multiple patterns of virus cross-reactivity recognized by NS3-specific T-cell clones. J Virol 65:1823–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green S, Pichyangkul S, Vaughn DW, Kalayanarooj S, Nimmannitya S, Nisalak A, Kurane I, Rothman AL, Ennis FA. 1999. Early CD69 expression on peripheral blood lymphocytes from children with dengue hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis 180:1429–1435. doi: 10.1086/315072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yauch LE, Zellweger RM, Kotturi MF, Qutubuddin A, Sidney J, Peters B, Prestwood TR, Sette A, Shresta S. 2009. A protective role for dengue virus-specific CD8+ T cells. J Immunol 182:4865–4873. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiskopf D, Bangs DJ, Sidney J, Kolla RV, De Silva AD, de Silva AM, Crotty S, Peters B, Sette A. 2015. Dengue virus infection elicits highly polarized CX3CR1+ cytotoxic CD4+ T cells associated with protective immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E4256–E4263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505956112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Matos AM, Carvalho KI, Rosa DS, Villas-Boas LS, da Silva WC, Rodrigues CL, Oliveira OM, Levi JE, Araujo ES, Pannuti CS, Luna EJ, Kallas EG. 2015. CD8+ T lymphocyte expansion, proliferation and activation in dengue fever. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0003520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mongkolsapaya J, Dejnirattisai W, Xu XN, Vasanawathana S, Tangthawornchaikul N, Chairunsri A, Sawasdivorn S, Duangchinda T, Dong T, Rowland-Jones S, Yenchitsomanus PT, McMichael A, Malasit P, Screaton G. 2003. Original antigenic sin and apoptosis in the pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Nat Med 9:921–927. doi: 10.1038/nm887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green S, Vaughn DW, Kalayanarooj S, Nimmannitya S, Suntayakorn S, Nisalak A, Lew R, Innis BL, Kurane I, Rothman AL, Ennis FA. 1999. Early immune activation in acute dengue illness is related to development of plasma leakage and disease severity. J Infect Dis 179:755–762. doi: 10.1086/314680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathew A, Townsley E, Ennis FA. 2014. Elucidating the role of T cells in protection against and pathogenesis of dengue virus infections. Future Microbiol 9:411–425. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurane I, Kontny U, Janus J, Ennis FA. 1990. Dengue-2 virus infection of human mononuclear cell lines and establishment of persistent infections. Arch Virol 110:91–101. doi: 10.1007/BF01310705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mentor NA, Kurane I. 1997. Dengue virus infection of human T lymphocytes. Acta Virol 41:175–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mota J, Rico-Hesse R. 2011. Dengue virus tropism in humanized mice recapitulates human dengue fever. PLoS One 6:e20762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kou Z, Quinn M, Chen H, Rodrigo WW, Rose RC, Schlesinger JJ, Jin X. 2008. Monocytes, but not T or B cells, are the principal target cells for dengue virus (DV) infection among human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Med Virol 80:134–146. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durbin AP, Vargas MJ, Wanionek K, Hammond SN, Gordon A, Rocha C, Balmaseda A, Harris E. 2008. Phenotyping of peripheral blood mononuclear cells during acute dengue illness demonstrates infection and increased activation of monocytes in severe cases compared to classic dengue fever. Virology 376:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silveira GF, Meyer F, Delfraro A, Mosimann AL, Coluchi N, Vasquez C, Probst CM, Bafica A, Bordignon J, Dos Santos CN. 2011. Dengue virus type 3 isolated from a fatal case with visceral complications induces enhanced proinflammatory responses and apoptosis of human dendritic cells. J Virol 85:5374–5383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01915-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King AD, Nisalak A, Kalayanrooj S, Myint KS, Pattanapanyasat K, Nimmannitya S, Innis BL. 1999. B cells are the principal circulating mononuclear cells infected by dengue virus. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 30:718–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackley S, Kou Z, Chen H, Quinn M, Rose RC, Schlesinger JJ, Coppage M, Jin X. 2007. Primary human splenic macrophages, but not T or B cells, are the principal target cells for dengue virus infection in vitro. J Virol 81:13325–13334. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01568-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y, Maguire T, Hileman RE, Fromm JR, Esko JD, Linhardt RJ, Marks RM. 1997. Dengue virus infectivity depends on envelope protein binding to target cell heparan sulfate. Nat Med 3:866–871. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Germi R, Crance JM, Garin D, Guimet J, Lortat-Jacob H, Ruigrok RW, Zarski JP, Drouet E. 2002. Heparan sulfate-mediated binding of infectious dengue virus type 2 and yellow fever virus. Virology 292:162–168. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dalrymple N, Mackow ER. 2011. Productive dengue virus infection of human endothelial cells is directed by heparan sulfate-containing proteoglycan receptors. J Virol 85:9478–9485. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05008-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voskoboinik I, Whisstock JC, Trapani JA. 2015. Perforin and granzymes: function, dysfunction and human pathology. Nat Rev Immunol 15:388–400. doi: 10.1038/nri3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Limonta D, Torres G, Capo V, Guzman MG. 2008. Apoptosis, vascular leakage and increased risk of severe dengue in a type 2 diabetes mellitus patient. Diab Vasc Dis Res 5:213–214. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2008.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belmokhtar CA, Hillion J, Segal-Bendirdjian E. 2001. Staurosporine induces apoptosis through both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent mechanisms. Oncogene 20:3354–3362. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Correa AR, Berbel AC, Papa MP, Morais AT, Pecanha LM, Arruda LB. 2015. Dengue virus directly stimulates polyclonal B cell activation. PLoS One 10:e0143391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilgard P, Stockert R. 2000. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans initiate dengue virus infection of hepatocytes. Hepatology 32:1069–1077. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.18713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevenson M, Stanwick TL, Dempsey MP, Lamonica CA. 1990. HIV-1 replication is controlled at the level of T cell activation and proviral integration. EMBO J 9:1551–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villa NY, Wasserfall CH, Meacham AM, Wise E, Chan W, Wingard JR, McFadden G, Cogle CR. 2015. Myxoma virus suppresses proliferation of activated T lymphocytes yet permits oncolytic virus transfer to cancer cells. Blood 125:3778–3788. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-587329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurane I, Innis BL, Nimmannitya S, Nisalak A, Meager A, Janus J, Ennis FA. 1991. Activation of T lymphocytes in dengue virus infections. High levels of soluble interleukin 2 receptor, soluble CD4, soluble CD8, interleukin 2, and interferon-gamma in sera of children with dengue. J Clin Invest 88:1473–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bade B, Lohrmann J, ten Brinke A, Wolbink AM, Wolbink GJ, ten Berge IJ, Virchow JC Jr, Luttmann W, Hack CE. 2005. Detection of soluble human granzyme K in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Immunol 35:2940–2948. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marianneau P, Cardona A, Edelman L, Deubel V, Despres P. 1997. Dengue virus replication in human hepatoma cells activates NF-kappaB which in turn induces apoptotic cell death. J Virol 71:3244–3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Avirutnan P, Malasit P, Seliger B, Bhakdi S, Husmann M. 1998. Dengue virus infection of human endothelial cells leads to chemokine production, complement activation, and apoptosis. J Immunol 161:6338–6346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klomporn P, Panyasrivanit M, Wikan N, Smith DR. 2011. Dengue infection of monocytic cells activates ER stress pathways, but apoptosis is induced through both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. Virology 409:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu XN, Screaton GR, McMichael AJ. 2001. Virus infections: escape, resistance, and counterattack. Immunity 15:867–870. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibellini D, Re MC, Ponti C, Vitone F, Bon I, Fabbri G, Di Iasio GM, Zauli G. 2005. HIV-1 Tat protein concomitantly down-regulates apical caspase-10 and up-regulates c-FLIP in lymphoid T cells: a potential molecular mechanism to escape TRAIL cytotoxicity. J Cell Physiol 203:547–556. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geleziunas R, Xu W, Takeda K, Ichijo H, Greene WC. 2001. HIV-1 Nef inhibits ASK1-dependent death signalling providing a potential mechanism for protecting the infected host cell. Nature 410:834–838. doi: 10.1038/35071111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laskus T, Kibler KV, Chmielewski M, Wilkinson J, Adair D, Horban A, Stanczak G, Radkowski M. 2013. Effect of hepatitis C infection on HIV-induced apoptosis. PLoS One 8:e75921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Despres P, Frenkiel MP, Deubel V. 1993. Differences between cell membrane fusion activities of two dengue type-1 isolates reflect modifications of viral structure. Virology 196:209–219. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nogueira MB, Stella V, Bordignon J, Batista WC, Borba L, Silva LH, Hoffmann FG, Probst CM, Santos CN. 2008. Evidence for the co-circulation of dengue virus type 3 genotypes III and V in the Northern region of Brazil during the 2002-2004 epidemics. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 103:483–488. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762008000500013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gould EA, Clegg JCS. 1985. Growth, titration and purification of togaviruses, p 43–78. In Mahy BWJ. (ed), Virology: a practical approach. IRL Press, Oxford, England. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuczera D, Bavia L, Mosimann AL, Koishi AC, Mazzarotto GA, Aoki MN, Mansano AM, Tomeleri EI, Costa Junior WL, Miranda MM, Lo Sarzi M, Pavanelli WR, Conchon-Costa I, Duarte Dos Santos CN, Bordignon J. 2016. Isolation of dengue virus serotype 4 genotype II from a patient with high viral load and a mixed Th1/Th17 inflammatory cytokine profile in South Brazil. Virol J 13:93. doi: 10.1186/s12985-016-0548-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.