ABSTRACT

All human influenza pandemics have originated from avian influenza viruses. Although multiple changes are needed for an avian virus to be able to transmit between humans, binding to human-type receptors is essential. Several research groups have reported mutations in H5N1 viruses that exhibit specificity for human-type receptors and promote respiratory droplet transmission between ferrets. Upon detailed analysis, we have found that these mutants exhibit significant differences in fine receptor specificity compared to human H1N1 and H3N2 and retain avian-type receptor binding. We have recently shown that human influenza viruses preferentially bind to α2-6-sialylated branched N-linked glycans, where the sialic acids on each branch can bind to receptor sites on two protomers of the same hemagglutinin (HA) trimer. In this binding mode, the glycan projects over the 190 helix at the top of the receptor-binding pocket, which in H5N1 would create a stearic clash with lysine at position 193. Thus, we hypothesized that a K193T mutation would improve binding to branched N-linked receptors. Indeed, the addition of the K193T mutation to the H5 HA of a respiratory-droplet-transmissible virus dramatically improves both binding to human trachea epithelial cells and specificity for extended α2-6-sialylated N-linked glycans recognized by human influenza viruses.

IMPORTANCE Infections by avian H5N1 viruses are associated with a high mortality rate in several species, including humans. Fortunately, H5N1 viruses do not transmit between humans because they do not bind to human-type receptors. In 2012, three seminal papers have shown how these viruses can be engineered to transmit between ferrets, the human model for influenza virus infection. Receptor binding, among others, was changed, and the viruses now bind to human-type receptors. Receptor specificity was still markedly different compared to that of human influenza viruses. Here we report an additional mutation in ferret-transmissible H5N1 that increases human-type receptor binding. K193T seems to be a common receptor specificity determinant, as it increases human-type receptor binding in multiple subtypes. The K193T mutation can now be used as a marker during surveillance of emerging viruses to assess potential pandemic risk.

KEYWORDS: H5N1, influenza, N-linked glycan, receptor binding, sialic acid, glycan array

INTRODUCTION

Avian influenza viruses sporadically infect humans and raise concern for becoming a new pandemic virus in a human population that has no immunity from prior exposure. Since 1997, there have been 856 human H5N1 infections reported, with a mortality rate of 60%, but fortunately, the virus has not acquired the ability to transmit between humans (1). The inability of avian viruses to transmit between humans is partly due to the lack of binding to human-type receptors (2–5). While all influenza viruses bind to sialic acid-containing receptors, human viruses are specific for receptors with sialic acid in an α2-6 linkage to the penultimate galactose (human type), whereas avian viruses bind to sialic acid in an α2-3 linkage (avian type) (2, 3, 6–9). Although this binary specificity is accepted as a species barrier, the sialic acid linkage to a galactose is merely a terminal structure that is part of a more complex glycan. Recent efforts by others and us have shown that many human viruses exhibit preferential specificity for a subset of human-type receptors comprising extended multiantennary N-glycans with branches that can bind simultaneously to two subunits of a hemagglutinin (HA) trimer (10–15).

In 2012, several reports demonstrated that engineered mutant H5N1 viruses that acquired the ability to bind human-type receptors could undergo respiratory droplet transmission between ferrets (4, 5, 16). Ferrets are a well-accepted model for human influenza disease, as they display similar clinical symptoms and can transmit human viruses by sneezing (17). Their respiratory tract glycome is also very similar to that of humans (18, 19). In two separate studies, viruses with H5 HAs from the A/Vietnam/1203/04 (VN1203) or A/Indonesia/5/05 (INDO05) strain were engineered via two mutations in the receptor-binding site (RBS), which is known to promote binding to human-type receptors, and were then serially passaged in ferrets, where they acquired additional mutations that impacted receptor specificity. The HAs of both viruses lost an N-linked glycan at N158 on the edge of the RBS that enhanced binding to human-type receptors and acquired a stabilizing mutation in the stalk (4, 5, 20–23).

Although the ferret-transmissible H5N1 viruses exhibited increased binding to human-type receptors, in one case, they retained binding to avian-type receptors, and the two mutant viruses recognized different subsets of human-type receptors (10, 20). Recently, we found that H3N2 and the 2009 pandemic H1N1 viruses bind selectively to a subset of human-type receptors comprising poly-N-acetyl-lactosamine (poly-LacNAc)-extended N-linked glycans (14, 24). Such N-linked glycans with LacNAc repeats on their antennae have been reported in human and ferret respiratory tissues and in a human airway epithelial cell line (18, 25, 26). HA mutations that conferred similar human-type receptor specificity were also found for H7N9, H10N8, and H6N1 avian viruses (27–29). In all cases, the mutations allowed the α2-6-sialylated receptor glycan to extend from one RBS and project over the 190 helix in a way that would allow the other branch of the glycan to engage the second RBS of the same trimer. Interestingly, a key mutation conferring human-type receptor specificity in H7 and H10 HAs was a K193T mutation, which would in principle allow the receptor glycan to project over the surface of the HA and promote bidentate binding (27–29).

Because the ferret-transmissible H5 viruses also contain K193, we investigated the impact of the K193T mutation on the receptor specificity of HA to see if there would be a further shift toward the receptor specificity of human influenza viruses (14). Remarkably, we find that this additional mutation in the background of ferret-transmissible H5 HA has a profound effect, conferring specificity for human-type receptors comparable to that of human H3N2 and 2009 H1N1 pandemic viruses. This change in specificity is further reflected in the loss of binding to chicken trachea epithelial cells and increased binding to human trachea epithelial cells.

RESULTS

HAs from ferret-transmissible H5N1 viruses do not recapitulate the receptor specificity of human viruses.

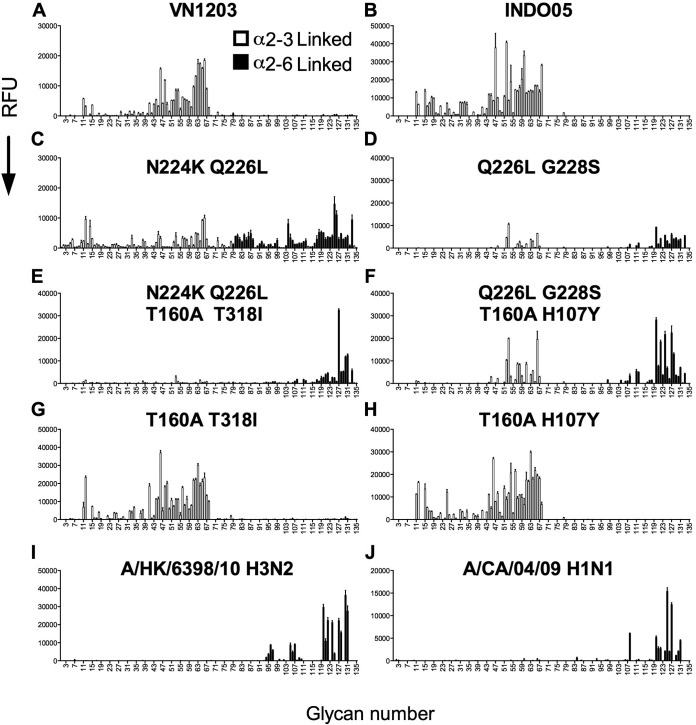

Previous studies on the specificity of ferret-transmissible H5N1 viruses used glycan microarrays that were missing poly-LacNAc-extended N-linked glycans that are preferred by recent human H3N2 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 viruses (14, 20). Accordingly, we reassessed their specificity on an expanded glycan array containing these extended N-linked glycans (see the complete list in Table S1 in the supplemental material) (18, 25). The wild-type (WT) HAs from the H5N1 VN1203 and INDO05 strains used in the ferret transmission experiments bound solely to α2-3-linked avian-type receptors (Fig. 1A and B). Engineered RBS mutations known to enable human-type receptor specificity on VN1203 (N224K Q226L) and INDO05 (Q226L G228S) both showed binding to a mix of avian- and human-type receptors (Fig. 1C and D). The addition of the mutations acquired during subsequent transmission in ferrets to VN1203 (T160A T318I) and INDO05 (T160A H107Y) led to more-avid binding to human-type receptors, aided by the loss of an N-linked glycan at N158 on the tip of HA resulting from the T160A mutation (Fig. 1E and F). Notably, however, the transmissible INDO05 mutant retained binding to avian-type receptors (Fig. 1F). Engineered HAs that contained only mutations that remove the glycan at position 158 (T160A) and influenced stability in the stem (T318I or H107Y) showed wild-type avian-type specificity, showing the importance of the engineered RBS mutations N224K Q226L and Q226L G228S in conferring human-type receptor specificity (Fig. 1G and H). Results for HA proteins from exemplary human H3N2 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 viruses illustrate a preferred specificity for a subset of human-type receptors (Fig. 1I and J) that overlaps the specificity of the ferret-transmissible H5 viruses.

FIG 1.

Receptor specificities of WT H5 and the transmissible mutants. Glycan microarray analysis was used to determine the receptor specificities of VN1203 and INDO05 WT and mutant HAs, including WT VN1203 (A), WT INDO05 (B), VN1203 N224K Q226L (C), INDO05 Q226L G228S (D), VN1203 T160A N224K Q226L T318I (E), INDO05 H107Y T160A Q226L G228S (F), VN1203 T160A T318I (G), and INDO05 H107Y T160A (H), and human HA proteins of a recent H3N2 A/HK/6398/10 strain (I) and the 2009 pandemic H1N1 A/CA/04/09 strain (J). The mean signals and standard errors were calculated from six independent replicates. The data shown are representative of results from three independent assays. α2-3-linked sialosides (glycans 11 to 79 on the x axis) and α2-6-linked sialosides (glycans 80 to 135) are shown. Glycans 1 to 10 are nonsialylated controls (see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). RFU, relative fluorescence units.

The K193T mutation increases human-type receptor binding.

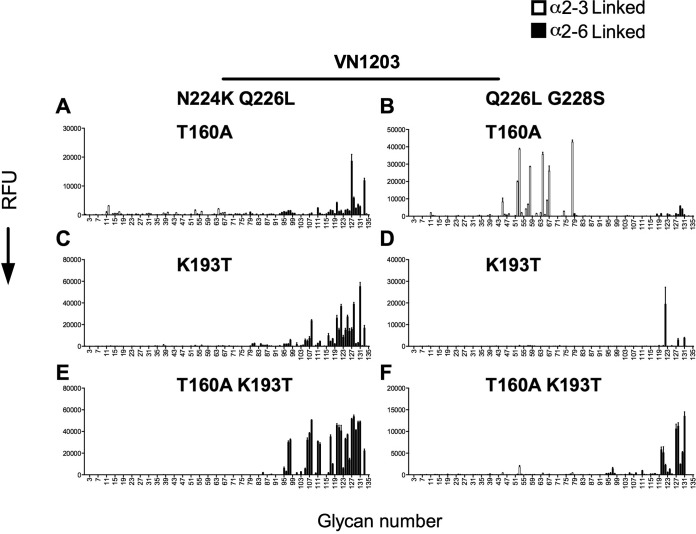

The engineered mutations in the VN1203 and INDO05 ferret-transmissible strains comprised one common mutation (Q226L) and one different mutation (N224K and G228S) (4, 5, 30). To study the impact of the K193T mutation with and without the glycan mutation (T160A), we looked at both sets of mutations in the VN1203 background. The K193T mutation by itself has no effect on the receptor specificity of VN1203 HA (not shown), as we have also seen for avian H7 and H10 HAs. HAs with N224K Q226L and T160A mutations have a specificity similar to those of the corresponding transmissible mutants with the additional stem mutation (compare Fig. 2A and 1E). However, in the VN1203 background, H5 with the Q226L G228S T160A mutation retained binding to avian-type receptors (Fig. 2B), while the corresponding transmissible INDO05 mutant bound both avian-type and human-type receptors (Fig. 1F). The introduction of the K193T mutation increased binding to human-type receptors in the N224K Q226L background and abolished binding to avian-type receptors while showing weak binding to three human-type N-linked glycan receptors in the Q226L G228S background (Fig. 2C and D). The further addition of the T160A mutation, which removes the glycan at position 158, dramatically increased binding to a wider range of human-type receptors (Fig. 2E and F). We thus conclude that removal of the bulky K193 residue and the N-glycan on the tip of the RBS of H5 facilitates binding to human-type receptors.

FIG 2.

Receptor specificities of two sets of VN1203 H5 mutants. Glycan microarray analysis was used to determine the receptor specificities of HAs of the VN1203 T160A N224K Q226L (A), VN1203 T160A Q226L G228S (B), VN1203 K193T N224K Q226L (C), VN1203 K193T Q226L G228S (D), VN1203 T160A K193T N224K Q226L (E), and VN1203 T160A K193T Q226L G228S (F) mutants. The mean signals and standard errors were calculated from six independent replicates. The data shown are representative of results from three independent assays. α2-3-linked sialosides (glycans 11 to 79 on the x axis) and α2-6-linked sialosides (glycans 80 to 135) are shown. Glycans 1 to 10 are nonsialylated controls (see also Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Receptor-binding avidity of H5 mutant proteins.

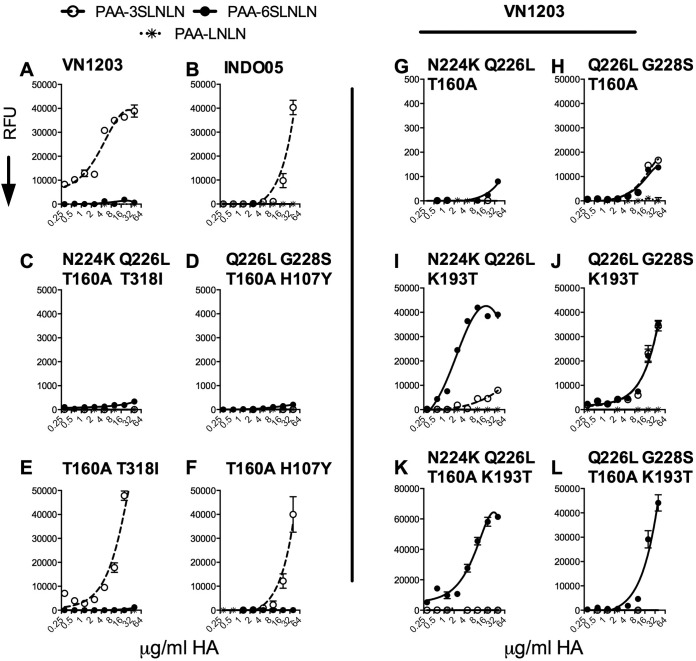

To further characterize human-type receptor binding, we analyzed the relative avidities of all the mutants using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-like assay. This ELISA is based on a multiwell glycan array format evaluating the binding of HA at increasing concentrations to human- or avian-type receptors linked to polyacrylamide (PAA) polymers bound to the slide surface (31). Both H5 WT proteins bound with high avidity to avian-type receptors, with no binding to human-type receptors (Fig. 3A and B), in agreement with the findings of the sialoside arrays. Both the transmissible VN1203 and INDO05 mutants lost binding to avian-type receptors and also showed no binding to human-type receptors in this assay (Fig. 3C and D). This result is consistent with these mutations reducing the avidity for receptors (21), and the receptors in this assay are not the N-linked glycans bound on the glycan array. The HAs with only the stalk and glycosylation mutations showed binding to avian-type receptors similar to that of wild-type HAs (Fig. 3E and F).

FIG 3.

Determination of receptor-binding avidities of WT H5 and all the mutants. An ELISA-like assay was used to determine the binding avidities of WT VN1203 (A), WT INDO05 (B), VN1203 T160A N224K Q226L T318I (C), INDO05 H107Y T160A Q226L G228S (D), VN1203 T160A T318I (E), INDO05 H107Y T160A (F), VN1203 T160A N224K Q226L (G), VN1203 T160A Q226L G228S (H), VN1203 K193T N224K Q226L (I), VN1203 K193T Q226L G228S (J), VN1203 T160A K193T N224K Q226L (K), and VN1203 T160A K193T Q226L G228S (L). The mean signals and standard errors were calculated from six independent replicates in the ELISA-like assay. The data shown are representative of results from three independent assays. In this array, α2-3-linked sialylated di-LacNAc (3SLNLN), α2-6-linked sialylated di-LacNAc (6SLNLN), and nonsialylated di-LacNAc (LNLN) are shown.

To assess the impact of the K193 mutation on avidity, we used the VN1203 background. The ferret-transmissible mutations N224K Q226L T160A (VN1203) and Q226L G228S T160A (INDO05) by themselves showed low avidities for both human- and avian-type receptors in this assay (Fig. 3G and H). The introduction of the K193T mutation in both RBS backgrounds (N224K Q226L and Q226L G228S) resulted in a significantly higher avidity for binding to human-type receptors (Fig. 3I and J). The removal of the N-glycan on the HA head of these triple mutants again resulted in higher affinities (Fig. 3K and L). From this, we conclude that the removal of the N-glycan together with the K193T mutation, which removes a bulky, charged residue in the receptor-binding domain, increase the binding avidity for human-type receptors.

High-avidity binding to human-type receptors increases binding to human tracheal epithelial cells.

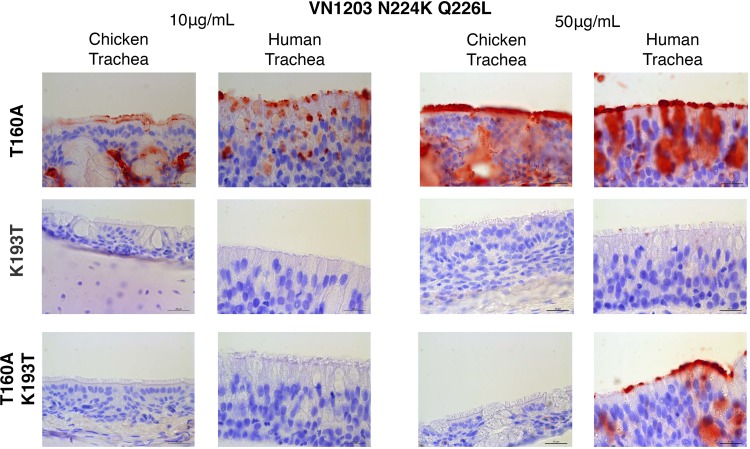

Because binding to human-type receptors is considered essential for influenza viruses to transmit between humans and is presumed to result from increased binding to human airway epithelial cells (3, 32), we analyzed the binding of these novel H5 mutants to chicken and human tracheal tissue sections. For VN1203 with the ferret-transmissible RBS and glycosylation mutations (N224K Q226L T160A), we observed binding to both chicken and human tracheal tissues (Fig. 4). For the VN1203 N224K Q226L K193T mutant, we were not able to show any binding to these tissues. Since this mutant bound avidly in the other assays, it points out a fundamental difference between receptor glycans displayed on artificial surfaces and natural glycans on cell surface glycoproteins and glycolipids. Finally, for the N224K Q226L T160A K193T mutant, we observed binding to human trachea tissues and no binding to chicken trachea tissues. Notably, a higher concentration of this H5 virus was required to observe staining, reflecting a lower avidity for human epithelial cells.

FIG 4.

Staining of chicken and human trachea tissues with VN1203 H5 mutants. Tissue staining of VN1203 T160A N224K Q226L, VN1203 K193T N224K Q226L, and VN1203 T160A K193T N224K Q226L at two different concentrations is shown. Tissue binding of HAs to either chicken or human tracheal sections was visualized by AEC staining.

The N-glycan on the head of H5 influences bidentate receptor binding.

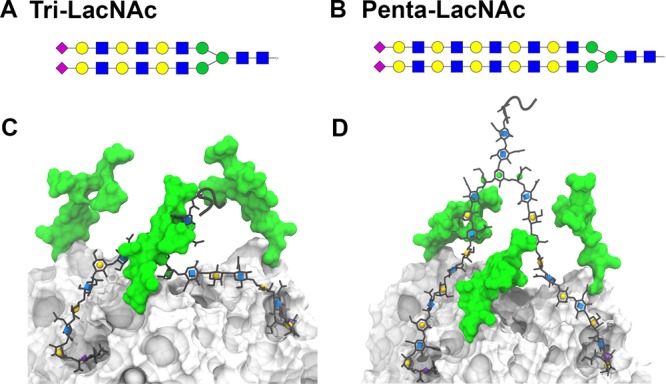

On the glycan array, the binding of the K193T mutant was highly restricted to N-glycans with 4 to 5 LacNAc repeats when the N-glycan at N158 was present (Fig. 2D). The absence of this N-glycan markedly increased binding in both the sialoside array and the ELISA-like assay (e.g., Fig. 2F, and compare Fig. 3I and J with K and L). Interestingly, binding to N-linked glycans with shorter LacNAc chains was increased with the removal of the N-glycan at position 158, in concert with the K193T mutation. To explain this phenomenon, we modeled the Man5 N-glycan on the head of the H5 VN1203 crystal structure (PDB accession number 2FK0) (33). Next, we modeled a bidentate binding event with an N-glycan with either 3 or 5 LacNAc repeats onto this structure. We observed that the N-glycan on the head of HA overlaps the tri-LacNAc-containing N-glycan but not the penta-LacNAc-containing N-glycan (Fig. 5), which corresponds with our binding data showing that the removal of this N-glycan increases binding to glycans with shorter LacNAc extensions.

FIG 5.

Proposed three-dimensional model for how the N-glycan at position 158 would inhibit binding to a human-type N-glycan with relatively short LacNAc repeats. (A and B) Biantennary N-glycan with 3 LacNAc repeats (A) and 5 LacNAc repeats (B). (C and D) HA surface, in gray, with N-glycans modeled with 3 LacNAc repeats (C) and with 5 LacNAc repeats (D). The N-glycan on HA is shown with a green surface and clashes with the N-glycan with 3 LacNAc repeats in multiple adopted shapes.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have analyzed the receptor-binding specificities of ferret-transmissible H5N1 viruses in more depth using an expanded sialoside glycan array that includes intact poly-LacNAc-extended N-linked glycans found in human and ferret airway tissues. We found that the HA proteins from the ferret-transmissible VN1203 and INDO05 strains are different from each other and only partially overlap the specificity of currently circulating human H1 and H3 influenza viruses. However, the glycans bound overlap a subset of human-type receptors that comprise poly-LacNAc-extended N-linked glycans. Upon the addition of the K193T mutation to ferret-transmissible H5N1, we observed enhanced human-type receptor binding. K193T can be considered a marker for binding to human-type receptors, as shown for H3, H5, H7, and H10 (28, 29, 34, 35), where the presence of a bulky side chain for avian HA subtypes or a serine or threonine for human HA subtypes is found.

We have observed that binding to human-type receptors on a sialoside array does not always correspond with binding to the human upper respiratory tract (29). One explanation is the low abundance of these glycans (25), or another possibility is that not all human respiratory tract glycans are represented on the array. A better understanding of the types of glycans present on the human respiratory epithelium and a glycan array representing these glycans are needed for predicting the biological relevance of mutations that switch avian-type receptor specificity to human-type receptor specificity (3, 26, 32, 36, 37).

In this study, we reassessed the receptor specificities of ferret-transmissible H5N1 mutants and showed that they bind N-linked glycans carrying human-type receptors. Recent human H3N2 and H1N1 viruses also bind these N-glycans with three or more LacNAc repeats on their antennae. This receptor specificity is still markedly different compared to that of H5N1, as H5 binds only a subset of human-type receptors and retains some avian-type receptor specificity. To improve human-type receptor binding, we introduced the K193T mutation and observed a significant increase in binding to α2-6-linked sialosides. The biological consequence of this mutation and that of other H5 mutant proteins that bind with apparent high avidity remain to be determined (38, 39). We have previously shown that recent H3N2 viruses specifically use branched N-glycans with multiple LacNAc repeats to successfully infect and replicate in MDCK cells (14), but knowledge on the importance of this common human-type receptor specificity profile for pathogenesis and transmission in our best animal model, the ferret, is severely lacking.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of HA for binding studies.

H5-encoding cDNAs (GenScript, USA) of A/Vietnam/1203/04/H5N1, A/Indonesia/05/05/H5N1, A/California/04/09/pdmH1N1, and A/Hong Kong/6398/10/H3N2 were cloned into the pCD5 expression vector as described previously (40). The pCD5 expression vector is adapted such that the HA-encoding cDNAs are cloned in frame with DNA sequences coding for a signal sequence, a GCN4 trimerization motif (RMKQIEDKIEEIESKQKKIENEIARIKK), and Strep-tag II (WSHPQFEK; IBA, Germany).

The HA proteins were expressed in HEK293S GnTI(−) cells and purified from the cell culture supernatants as described previously (40). pCD5 expression vectors were transfected into HEK293S GnTI(−) cells by using polyethyleneimine I (PEI). At 6 h posttransfection, the transfection mixture was replaced with 293 SFM II expression medium (Gibco) supplemented with sodium bicarbonate (3.7 g/liter), glucose (2.0 g/liter), Primatone RL-UF (3.0 g/liter), GlutaMAX (Gibco), and 1.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Tissue culture supernatants were harvested at 5 to 6 days posttransfection. HA proteins were purified by using Strep-Tactin Sepharose beads according to the manufacturer's instructions (IBA, Germany).

Glycan microarray binding of HA.

Purified, soluble trimeric HA was precomplexed with Alexa 488-linked anti-Strep-tag mouse antibody and Alexa 488-linked anti-mouse IgG (4:2:1 molar ratio) prior to incubation for 15 min on ice in 100 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–Tween (PBS-T) and incubated on the array surface in a humidified chamber for 90 min. Slides were subsequently washed by successive rinses with PBS-T, PBS, and deionized H2O. Washed arrays were dried by centrifugation and immediately scanned for a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) signal on a Perkin-Elmer ProScanArray Express confocal microarray scanner. The fluorescent signal intensity was measured by using Imagene (Biodiscovery), and the mean intensity minus the mean background was calculated and graphed by using MS Excel. For each glycan, the mean signal intensity was calculated from 6 replicates spots. The highest and lowest signals of the 6 replicates were removed, and the remaining 4 replicates were used to calculate the mean signal, standard deviation (SD), and standard error measurement (SEM). Bar graphs represent the averaged mean signal minus the background for each glycan sample, and error bars are the SEM values. A list of glycans on the microarray is included in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

ELISA-like assay.

In the ELISA-like assay, microwell slides were printed to contain six replicates of 3SLNLN-, 6SLNLN-, and LNLN-PAA (where LN stands for LacNAc), and the assay was done the same way as for the glycan microarray, with some differences (31). The microwell slide contained 48 identical arrays that were incubated with 8 μl of the analyte. A total of 40 μg/ml of precomplexed HA was serially diluted in a 384-well plate and incubated for 10 min on ice. This solution was transferred to the microwell arrays and incubated for 90 min in a humidified chamber. Washes, scanning, and analyses were carried out as described above for the glycan microarray.

Tissue staining.

Sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded human and chicken trachea tissues were obtained from the University Medical Center, Utrecht University, The Netherlands, and the Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, The Netherlands, respectively. Tissue sections were rehydrated in series of alcohol from 100%, 96%, and 70% and finally rehydrated in distilled water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 1% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min. Tissue slides were boiled in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 min at 900 kW in a microwave for antigen retrieval and washed in PBS-T three times. Tissues were subsequently incubated with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS-T overnight at 4°C. The next day, the purified, soluble trimeric HA was precomplexed with mouse anti-Strep-tag–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) antibodies (IBA) and goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibodies (Life Biosciences) at a ratio of 4:2:1 in PBS-T with 3% BSA and incubated on ice for 15 min. After draining of the slide, precomplexed HA was applied onto the tissue and incubated for 90 min. Sections were then washed in PBS-T, incubated with 3-amino-9-ethyl-carbazole (AEC; Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min, counterstained with hematoxylin, and mounted with Aquatex (Merck). Images were taken by using a charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera and an Olympus BX41 microscope linked to CellB imaging software (Soft Imaging Solutions GmbH, Münster, Germany).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded in part by National Institutes of Health grants AI114730 (to J.C.P) and U01 CA207824 and P41 GM103390 (to R.J.W.). This work was supported in part by the Scripps Microarray Core Facility. R.P.D.V. is a recipient of VENI and Rubicon grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). M.H.V. is a recipient of a MEERVOUD grant from the NWO. Several glycans used for HA binding assays were partially provided by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (http://www.functionalglycomics.org/), funded by NIGMS grant GM62116 (J.C.P.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02016-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harfoot R, Webby RJ. 2017. H5 influenza, a global update. J Microbiol 55:196–203. doi: 10.1007/s12275-017-7062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paulson JC, de Vries RP. 2013. H5N1 receptor specificity as a factor in pandemic risk. Virus Res 178:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Graaf M, Fouchier RA. 2014. Role of receptor binding specificity in influenza A virus transmission and pathogenesis. EMBO J 33:823–841. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herfst S, Schrauwen EJ, Linster M, Chutinimitkul S, de Wit E, Munster VJ, Sorrell EM, Bestebroer TM, Burke DF, Smith DJ, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2012. Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets. Science 336:1534–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1213362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai M, Watanabe T, Hatta M, Das SC, Ozawa M, Shinya K, Zhong G, Hanson A, Katsura H, Watanabe S, Li C, Kawakami E, Yamada S, Kiso M, Suzuki Y, Maher EA, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. 2012. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature 486:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nature10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matrosovich M, Tuzikov A, Bovin N, Gambaryan A, Klimov A, Castrucci MR, Donatelli I, Kawaoka Y. 2000. Early alterations of the receptor-binding properties of H1, H2, and H3 avian influenza virus hemagglutinins after their introduction into mammals. J Virol 74:8502–8512. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.18.8502-8512.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers GN, D'Souza BL. 1989. Receptor binding properties of human and animal H1 influenza virus isolates. Virology 173:317–322. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers GN, Paulson JC. 1983. Receptor determinants of human and animal influenza virus isolates: differences in receptor specificity of the H3 hemagglutinin based on species of origin. Virology 127:361–373. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers GN, Paulson JC, Daniels RS, Skehel JJ, Wilson IA, Wiley DC. 1983. Single amino acid substitutions in influenza haemagglutinin change receptor binding specificity. Nature 304:76–78. doi: 10.1038/304076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nycholat CM, McBride R, Ekiert DC, Xu R, Rangarajan J, Peng W, Razi N, Gilbert M, Wakarchuk W, Wilson IA, Paulson JC. 2012. Recognition of sialylated poly-N-acetyllactosamine chains on N- and O-linked glycans by human and avian influenza A virus hemagglutinins. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 51:4860–4863. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bateman AC, Karamanska R, Busch MG, Dell A, Olsen CW, Haslam SM. 2010. Glycan analysis and influenza A virus infection of primary swine respiratory epithelial cells: the importance of NeuAcα2-6 glycans. J Biol Chem 285:34016–34026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Vries RP, de Vries E, Martinez-Romero C, McBride R, van Kuppeveld FJ, Rottier PJ, Garcia-Sastre A, Paulson JC, de Haan CA. 2013. Evolution of the hemagglutinin protein of the new pandemic H1N1 influenza virus: maintaining optimal receptor binding by compensatory substitutions. J Virol 87:13868–13877. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01955-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Vries RP, de Vries E, Moore KS, Rigter A, Rottier PJ, de Haan CA. 2011. Only two residues are responsible for the dramatic difference in receptor binding between swine and new pandemic H1 hemagglutinin. J Biol Chem 286:5868–5875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.193557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng W, de Vries RP, Grant OC, Thompson AJ, McBride R, Tsogtbaatar B, Lee PS, Razi N, Wilson IA, Woods RJ, Paulson JC. 2017. Recent H3N2 viruses have evolved specificity for extended, branched human-type receptors, conferring potential for increased avidity. Cell Host Microbe 21:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrd-Leotis L, Liu R, Bradley KC, Lasanajak Y, Cummings SF, Song X, Heimburg-Molinaro J, Galloway SE, Culhane MR, Smith DF, Steinhauer DA, Cummings RD. 2014. Shotgun glycomics of pig lung identifies natural endogenous receptors for influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E2241–E2250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323162111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen LM, Blixt O, Stevens J, Lipatov AS, Davis CT, Collins BE, Cox NJ, Paulson JC, Donis RO. 2012. In vitro evolution of H5N1 avian influenza virus toward human-type receptor specificity. Virology 422:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith W, Andrewes CH, Laidlaw PP. 1933. A virus obtained from influenza patients. Lancet ii:66–68. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia N, Barclay WS, Roberts K, Yen HL, Chan RW, Lam AK, Air G, Peiris JS, Dell A, Nicholls JM, Haslam SM. 2014. Glycomic characterization of respiratory tract tissues of ferrets: implications for its use in influenza A virus infection studies. J Biol Chem 289:28489–28504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.588541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng PS, Bohm R, Hartley-Tassell LE, Steen JA, Wang H, Lukowski SW, Hawthorne PL, Trezise AE, Coloe PJ, Grimmond SM, Haselhorst T, von Itzstein M, Paton AW, Paton JC, Jennings MP. 2014. Ferrets exclusively synthesize Neu5Ac and express naturally humanized influenza A virus receptors. Nat Commun 5:5750. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Vries RP, Zhu X, McBride R, Rigter A, Hanson A, Zhong G, Hatta M, Xu R, Yu W, Kawaoka Y, de Haan CA, Wilson IA, Paulson JC. 2014. Hemagglutinin receptor specificity and structural analyses of respiratory droplet-transmissible H5N1 viruses. J Virol 88:768–773. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02690-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong X, Coombs PJ, Martin SR, Liu J, Xiao H, McCauley JW, Locher K, Walker PA, Collins PJ, Kawaoka Y, Skehel JJ, Gamblin SJ. 2013. Receptor binding by a ferret-transmissible H5 avian influenza virus. Nature 497:392–396. doi: 10.1038/nature12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W, Shi Y, Lu X, Shu Y, Qi J, Gao GF. 2013. An airborne transmissible avian influenza H5 hemagglutinin seen at the atomic level. Science 340:1463–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.1236787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linster M, van Boheemen S, de Graaf M, Schrauwen EJ, Lexmond P, Manz B, Bestebroer TM, Baumann J, van Riel D, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Matrosovich M, Fouchier RA, Herfst S. 2014. Identification, characterization, and natural selection of mutations driving airborne transmission of A/H5N1 virus. Cell 157:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens J, Chen LM, Carney PJ, Garten R, Foust A, Le J, Pokorny BA, Manojkumar R, Silverman J, Devis R, Rhea K, Xu X, Bucher DJ, Paulson JC, Cox NJ, Klimov A, Donis RO. 2010. Receptor specificity of influenza A H3N2 viruses isolated in mammalian cells and embryonated chicken eggs. J Virol 84:8287–8299. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00058-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walther T, Karamanska R, Chan RW, Chan MC, Jia N, Air G, Hopton C, Wong MP, Dell A, Malik Peiris JS, Haslam SM, Nicholls JM. 2013. Glycomic analysis of human respiratory tract tissues and correlation with influenza virus infection. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003223. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandrasekaran A, Srinivasan A, Raman R, Viswanathan K, Raguram S, Tumpey TM, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. 2008. Glycan topology determines human adaptation of avian H5N1 virus hemagglutinin. Nat Biotechnol 26:107–113. doi: 10.1038/nbt1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Vries RP, Tzarum N, Peng W, Thompson AJ, Ambepitiya Wickramasinghe IN, de la Pena ATT, van Breemen MJ, Bouwman KM, Zhu X, McBride R, Yu W, Sanders RW, Verheije MH, Wilson IA, Paulson JC. 2017. A single mutation in Taiwanese H6N1 influenza hemagglutinin switches binding to human-type receptors. EMBO Mol Med 9:1314–1325. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201707726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Vries RP, Peng W, Grant OC, Thompson AJ, Zhu X, Bouwman KM, de la Pena ATT, van Breemen MJ, Ambepitiya Wickramasinghe IN, de Haan CAM, Yu W, McBride R, Sanders RW, Woods RJ, Verheije MH, Wilson IA, Paulson JC. 2017. Three mutations switch H7N9 influenza to human-type receptor specificity. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006390. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzarum N, de Vries RP, Peng W, Thompson AJ, Bouwman KM, McBride R, Yu W, Zhu X, Verheije MH, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2017. The 150-loop restricts the host specificity of human H10N8 influenza virus. Cell Rep 19:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevens J, Blixt O, Chen LM, Donis RO, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2008. Recent avian H5N1 viruses exhibit increased propensity for acquiring human receptor specificity. J Mol Biol 381:1382–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McBride R, Paulson JC, de Vries RP. 2016. A miniaturized glycan microarray assay for assessing avidity and specificity of influenza A virus hemagglutinins. J Vis Exp 2016:e53847. doi: 10.3791/53847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Riel D, Munster VJ, de Wit E, Rimmelzwaan GF, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Kuiken T. 2007. Human and avian influenza viruses target different cells in the lower respiratory tract of humans and other mammals. Am J Pathol 171:1215–1223. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens J, Blixt O, Tumpey TM, Taubenberger JK, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2006. Structure and receptor specificity of the hemagglutinin from an H5N1 influenza virus. Science 312:404–410. doi: 10.1126/science.1124513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Poucke S, Doedt J, Baumann J, Qiu Y, Matrosovich T, Klenk HD, Van Reeth K, Matrosovich M. 2015. Role of substitutions in the hemagglutinin in the emergence of the 1968 pandemic influenza virus. J Virol 89:12211–12216. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01292-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamada S, Suzuki Y, Suzuki T, Le MQ, Nidom CA, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Muramoto Y, Ito M, Kiso M, Horimoto T, Shinya K, Sawada T, Kiso M, Usui T, Murata T, Lin Y, Hay A, Haire LF, Stevens DJ, Russell RJ, Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ, Kawaoka Y. 2006. Haemagglutinin mutations responsible for the binding of H5N1 influenza A viruses to human-type receptors. Nature 444:378–382. doi: 10.1038/nature05264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grant OC, Smith HMK, Firsova D, Fadda E, Woods RJ. 2014. Presentation, presentation, presentation! Molecular level insight into linker effects on glycan array screening data. Glycobiology 24:17–25. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwt083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lakdawala SS, Jayaraman A, Halpin RA, Lamirande EW, Shih AR, Stockwell TB, Lin X, Simenauer A, Hanson CT, Vogel L, Paskel M, Minai M, Moore I, Orandle M, Das SR, Wentworth DE, Sasisekharan R, Subbarao K. 2015. The soft palate is an important site of adaptation for transmissible influenza viruses. Nature 526:122–125. doi: 10.1038/nature15379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiong X, Xiao H, Martin SR, Coombs PJ, Liu J, Collins PJ, Vachieri SG, Walker PA, Lin YP, McCauley JW, Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ. 2014. Enhanced human receptor binding by H5 haemagglutinins. Virology 456–457:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tharakaraman K, Raman R, Viswanathan K, Stebbins NW, Jayaraman A, Krishnan A, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. 2013. Structural determinants for naturally evolving H5N1 hemagglutinin to switch its receptor specificity. Cell 153:1475–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Vries RP, de Vries E, Bosch BJ, de Groot RJ, Rottier PJ, de Haan CA. 2010. The influenza A virus hemagglutinin glycosylation state affects receptor-binding specificity. Virology 403:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.