LETTER

Mucormycosis is probably the most devastating and hard-to-diagnose invasive mold infection caused by fungi belonging to the order Mucorales. Rhizopus species are known to be responsible for >70% of all cases of mucormycosis and occur in immunocompromised patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, malignant hematologic disorders, or immunosuppressive therapy, with dramatic mortality rates ranging between 40 and 70% (1, 2). Options for antifungal and effective nontoxic therapy of mucormycosis are still very limited and are represented in practice only by lipid formulations of amphotericin B alone or amphotericin B in combination with echinocandins or azoles in salvage therapy (3).

Mucormycosis results in extensive angioinvasion that damages vascular endothelial cells, with subsequent vessel thrombosis and tissue necrosis (4, 5). Recently, GRP78 protein (a 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein, also known as binding immunoglobulin protein [BiP]) was identified in vivo as the endothelial cell receptor interacting with the mucormycosis ligand spore-coating protein homolog (CotH3) during angioinvasion (6, 7). Herein, we demonstrate for the first time the immunohistochemical presence of GRP78 expression associated with or in close proximity to angioinvasive Rhizopus oryzae in a patient with rhinocerebral mucormycosis.

A 45-year-old male patient developed aggressive therapy-refractory ocular and cerebral mucormycosis following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) from a matched related donor due to high-risk Philadelphia/BCR-ABL1-positive acute B-lineage lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). First-line therapy (according to a German ALL protocol, GMALL07/03) had resulted in complete remission, followed by a high-dose chemoradiation conditioning regimen, before HSCT and consisted of total body irradiation with 12 Gy, cyclophosphamide at 120 mg/kg of body weight, and antithymocyte globulin at 60 mg/kg of body weight. Antifungal prophylaxis was performed with fluconazole in the posttransplant period (200 mg per os [p.o.] daily). Five months posttransplantation, while still in remission of the acute leukemia and under fluconazole prophylaxis, the patient developed miosis, ptosis, and a painful swollen eyelid on the right side and was admitted to the hospital. On the day of admission, prophylaxis with fluconazole was stopped, and antifungal therapy was switched to oral posaconazole (600 mg p.o. daily in a form of a suspension). Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed sinusitis maxillaris, ethmoidalis, and sphenoidalis, with a consecutive subperiosteal abscess formation alongside the medial orbital wall and suspicion of cavernous sinus thrombosis despite broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy (Fig. 1). Transnasal ethmoidectomy followed by microscopy of the aspiration material revealed branched aseptate hyphae, partly located around blood vessels. Culture examination revealed Rhizopus oryzae. Antifungal susceptibility testing was not performed. Oral posaconazole prophylaxis was switched to parenteral liposomal amphotericin B, starting with daily dosage of 3 mg/kg of body weight. Due to progressive disease, the dosage was escalated to 5 mg/kg of body weight in salvage therapy. Repeated surgical interventions, including right eye enucleation, were performed; a triple regimen (liposomal amphotericin B, posaconazole, terbinafine) was started 10 days after the second surgery. Nevertheless, the patient succumbed 10 months posttransplantation to progressive invasive mycosis.

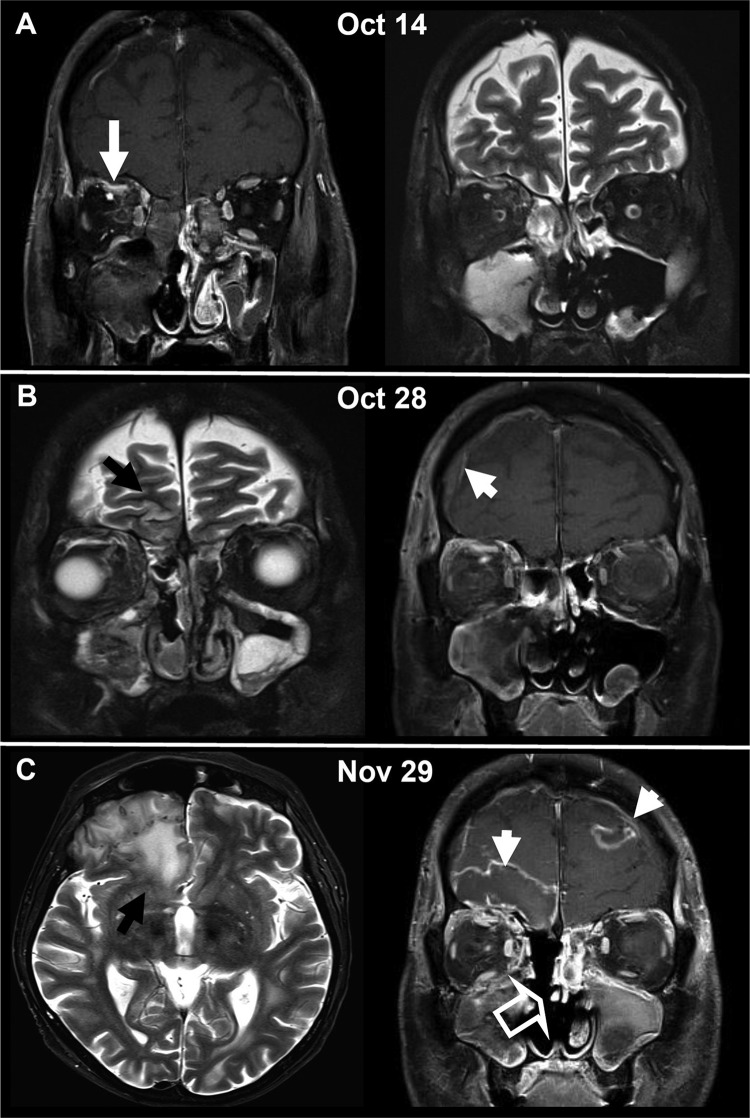

FIG 1.

Cranial MRI illustrating the progression of cerebral and orbital involvement of mucormycosis with R. oryzae over a time span of 6 weeks. (A) Initial scan showing the obliterated maxillary and ethmoidal sinuses on the right side and the orbital phlegmonous infection as well as a small subperiosteal abscess under the orbital roof (white arrow). (B) Progressive disease 2 weeks after the initial scan with diffuse edema and reticular contrast enhancement in the right retroorbital space. Signs of intracranial per continuitatem dissemination with frontobasal cortical edema (black arrow) and meningeal contrast enhancement (white arrowhead) are evident. Despite surgery, acute inflammatory mucosal swelling of the right maxilla persisted. (C) With further progression 6 weeks after the initial scan, the patient exhibited massive perifocal edema in the frontobasal brain parenchyma (black arrow), a mild frontal midline shift, and a typical MRI appearance of an intracranial abscess with central necrosis and intense peripheral contrast enhancement (white arrowheads). Progressive inflammatory changes in the left frontal and the left maxillary sinus after resection of the right ethmoid cellulae and the right lower and middle concha (open arrow) were observed.

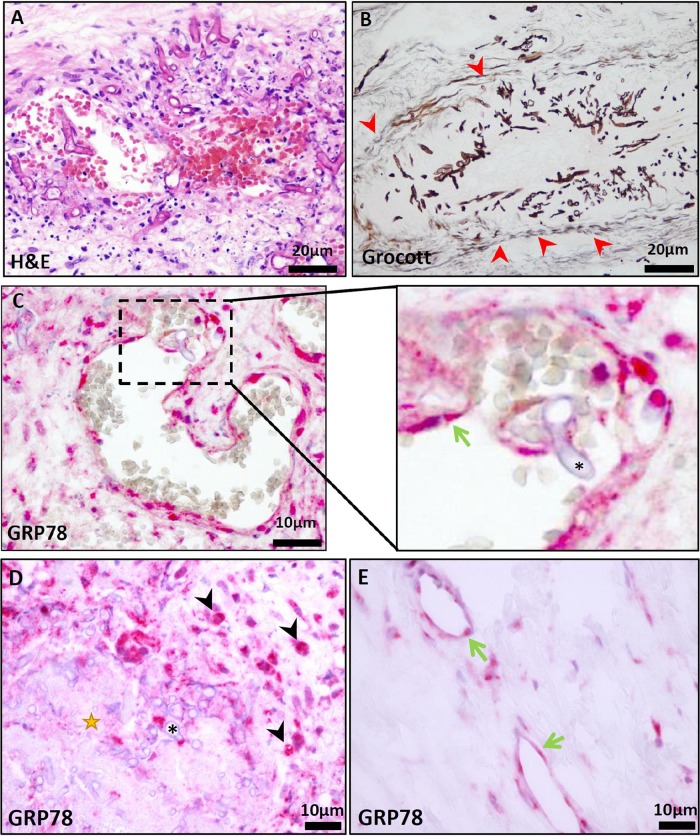

We performed immunohistochemistry from bioptic material of the ethmoidal sinus. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Grocott methenamine-silver staining (GMS) revealed mucormycosis with an angioinvasive character causing thrombosis and extensive necrosis (Fig. 2A and B). Endothelial GRP78 expression was illustrated by a commercial GRP78-specific antibody (GRP78/BiP, C50B12, 1:200; Cell Signaling Technology) (8). We could demonstrate a high in situ expression level of GRP78 on endothelial cells, especially those exposed to invading Rhizopus hyphae (Fig. 2C). GRP78 was also markedly expressed on infiltrating macrophages demarking necrotic areas (Fig. 2D). In comparison, endothelial cells not directly affected by Rhizopus presented markedly lower GRP78 staining intensity (Fig. 2E).

FIG 2.

(A) H&E staining of the resected sinoid mucosa presented angioinvasive mucormycosis, causing thrombosis and widespread necrotic areas (scale bar, 20 μm). (B) Grocott staining confirmed angioinvasive infiltration. Red arrowheads highlight a vessel wall infiltrated with R. oryzae organisms (scale bar, 20 μm). (C) Immunohistochemical GRP78 staining (GRP78/BiP, C50B12, 1:200; Cell Signaling Technology) demonstrated an intense expression on infiltrated endothelial cells (scale bar, 10 μm). (Inset in panel C) Higher magnification. The green arrow marks endothelial cells close to R. oryzae (*). (D) Black arrowheads highlight interstitial GRP78-positive macrophages demarking necrotic areas (star) infiltrated with R. oryzae (*) (scale bar, 10 μm). (E) GRP78 staining of endothelial cells (green arrows) not affected by R. oryzae in the same section demonstrates much lower expression levels (scale bar, 10 μm).

GRP78 was shown to be a receptor for Rhizopus during invasion and subsequent damage of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (6, 9). Coincidently, Mucorales cell surface proteins CotH2 and CotH3, presented exclusively by fungal members that cause mucormycosis, were identified to be the fungal ligands that adhere to GRP78 during invasion of the vasculature (7). Targeting GRP78 expression by genetic or antibody approach inhibited fungal penetration in host cells in vitro and in vivo (6, 10). However, such approaches were ineffective with other fungal pathogens, pointing toward a unique pathophysiology of mucormycosis (6). The discovery of endothelial cell receptor GRP78 as well as its ligands CotH2 and CotH3 enables an investigation of novel treatments aimed at disrupting their specific interaction, thereby halting angioinvasion. This report confirms the importance of GRP78 in mucormycosis pathogenesis in a real-life case scenario, warranting further intensive investigation of endothelial invasion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A.S.I. is supported by Public Health Service grant R01 AI063503. V.V. is supported by the Else-Kröner-Fresenius Foundation.

The informed consent for analysis of the postmortem material was obtained from the first-degree relatives.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, Sein M, Sein T, Chiou CC, Chu JH, Kontoyiannis DP, Walsh TJ. 2005. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis 41:634–653. doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, Roilides E, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP. 2012. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis 54(Suppl 1):S23–S34. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spellberg B, Ibrahim AS. 2010. Recent advances in the treatment of mucormycosis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 12:423–429. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0129-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP. 2012. Pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis 54(Suppl 1):S16–S22. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr, Ibrahim A. 2005. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 18:556–569. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.556-569.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu M, Spellberg B, Phan QT, Fu Y, Fu Y, Lee AS, Edwards JE Jr, Filler SG, Ibrahim AS. 2010. The endothelial cell receptor GRP78 is required for mucormycosis pathogenesis in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest 120:1914–1924. doi: 10.1172/JCI42164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gebremariam T, Liu M, Luo G, Bruno V, Phan QT, Waring AJ, Edwards JE Jr, Filler SG, Yeaman MR, Ibrahim AS. 2014. CotH3 mediates fungal invasion of host cells during mucormycosis. J Clin Invest 124:237–250. doi: 10.1172/JCI71349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkataramani V, Thiele K, Behnes CL, Wulf GG, Thelen P, Opitz L, Salinas-Riester G, Wirths O, Bayer TA, Schweyer S. 2012. Amyloid precursor protein is a biomarker for transformed human pluripotent stem cells. Am J Pathol 180:1636–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chibucos MC, Soliman S, Gebremariam T, Lee H, Daugherty S, Orvis J, Shetty AC, Crabtree J, Hazen TH, Etienne KA, Kumari P, O'Connor TD, Rasko DA, Filler SG, Fraser CM, Lockhart SR, Skory CD, Ibrahim AS, Bruno VM. 2016. An integrated genomic and transcriptomic survey of mucormycosis-causing fungi. Nat Commun 7:12218. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldin C, Ibrahim AS. 2017. Molecular mechanisms of mucormycosis—the bitter and the sweet. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006408. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]