ABSTRACT

The objectives of this study were to describe meropenem pharmacokinetics (PK) in plasma and/or subcutaneous adipose tissue (SCT) in critically ill patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) treatment and to develop a population PK model to simulate alternative dosing regimens and modes of administration. We conducted a prospective observational study. Ten patients on ECMO treatment received meropenem (1 or 2 g) intravenously over 5 min every 8 h. Serial SCT concentrations were determined using microdialysis and compared with plasma concentrations. A population PK model of SCT and plasma data was developed using NONMEM. Time above clinical breakpoint MIC for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8 mg/liter) was predicted for each patient. The following targets were evaluated: time for which the free (unbound) concentration is maintained above the MIC of at least 40% (40% fT>MIC), 100% fT>MIC, and 100% fT>4×MIC. For all dosing regimens simulated in both plasma and SCT, 40% fT>MIC was attained. However, prolonged meropenem infusion would be needed for 100% fT>MIC and 100% fT>4×MIC to be obtained. Meropenem plasma and SCT concentrations were associated with estimated creatinine clearance (eCLCr). Simulations showed that in patients with increased eCLCr, dose increment or continuous infusion may be needed to obtain therapeutic meropenem concentrations. In conclusion, our results show that using traditional targets of 40% fT>MIC for standard meropenem dosing of 1 g intravenously every 8 h is likely to provide sufficient meropenem concentration to treat the problematic pathogen P. aeruginosa for patients receiving ECMO treatment. However, for patients with an increased eCLCr, or if more aggressive targets, like 100% fT>MIC or 100% fT>4×MIC, are adopted, incremental dosing or continuous infusion may be needed.

KEYWORDS: beta-lactam, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, ECMO, microdialysis, target sites

INTRODUCTION

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) temporarily supports patients with severe heart and lung failure who are not responding to conventional treatment (1–4). ECMO is a life-supporting therapy, and in order to ensure successful liberation from this treatment, underlying conditions, such as an infection, must be treated simultaneously. ECMO is known to affect the pharmacokinetics (PK) of several drugs, including antimicrobials (5–8). Published data regarding antimicrobial PK in patients on ECMO is sparse and indicate significant PK changes, such as increased volume of distribution, decreased drug elimination, and sequestration of drugs in the ECMO circuit (5, 6). Thus, ECMO treatment increases the risk of subtherapeutic antimicrobial concentrations, which in this complex group of patients is associated with an increased risk of infection-related mortality.

Meropenem is a carbapenem with a broad spectrum of activity, commonly used empirically or targeted during ECMO treatment. Like other β-lactams, the antibacterial activity of carbapenems has been suggested to be time dependent, i.e., related to the time for which the free (unbound) concentration is maintained above the MIC (fT>MIC). For carbapenems, an fT>MIC of at least 40% is associated with maximum efficacy (9). However, the exact threshold for β-lactam antimicrobial exposure and clinical efficacy is still controversial. A recent meropenem pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) simulation study demonstrated that an fT>MIC of more than 40% is needed for adequate eradication of bacteria in patient populations (10). Several clinical studies suggest that an fT>MIC of 100% in plasma is associated with microbiological and clinical cures (11, 12), and plasma concentrations of up to 5-fold the MIC may be needed for maximum bactericidal activity in some patient populations (13).

In recent years, therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) has been increasingly used as a tool to ensure adequate antimicrobial dosing in critically ill patients. TDM and subsequent dose adjustments to meet patient PK alterations provides a more individualized approach to antimicrobial treatment (14, 15).

Despite the fact that most infections are located in tissues, antimicrobial dosing regimens are commonly based on plasma PK/PD indices. It is important to recognize the importance of reaching relevant antimicrobial concentrations at the site of infection, as suboptimal concentrations may result in therapeutic failure, especially for microorganisms with low antimicrobial susceptibility (16–19). To study the antimicrobial concentration-time course at the site of infection, invasive sampling techniques are required. However, this is not always possible. Microdialysis (MD) may be an attractive approach to overcome this task. MD is a minimal invasive technique that allows for sampling of antimicrobials from the interstitial fluid (ISF). This may help evaluate the PK variability commonly seen in critically ill patients, including patients receiving ECMO treatment (20, 21).

The aim of this study was to describe meropenem PK in plasma and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SCT) in critically ill patients receiving ECMO treatment. By developing a population PK model, meropenem PK in plasma and SCT was assessed and alternative dosing regimens and modes of administration were simulated.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics and meropenem concentrations.

Ten patients were included in the study, with their characteristics summarized and shown in Table 1. Dialysate concentrations for all patients except one, whose MD probe was malfunctioning, were included in the analysis. All patients had plasma samples taken during days 1 and 2, while plasma samples from eight and six patients were available from days 4 and 6, respectively. Mean (± standard deviations [SD]) relative recovery (RR) was 18.5% ± 5.2%. The mean (±SD) concentration in plasma and SCT at time zero was 25.5 ± 16.6 μg/ml and 31.5 ± 17.1 μg/ml, respectively. Seven patients received 1 g of meropenem, while three patients received 2 g of meropenem. All patients but one were treated with continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) simultaneously. Ultrasound confirmed correct location of all catheters.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristicsa (n = 10)

| Patient | Age (yr) | Sex | Wt (kg) | SOFA score | Temp (°C) | Pump speed (LPM) | Centrifugal pump speed (RPM) | Sweep gas flow (LPM) | Heparin dose (IE/h) | CRRT | Microbiologyb | Amt of: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-creatinine (μmol/liter) | Bilirubin (μmol/liter) | Albumin (g/liter) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 58 | F | 91 | 8 | 37.0 | 3.72 | 2,955 | 4.5 | 500 | Yes | IFV A1 | 133 | 17 | 27 |

| 2 | 30 | F | 55 | 9 | 35.9 | 3.42 | 2,660 | 3.5 | 200 | Yes | IFV A1 | 129 | 12 | 39 |

| 3 | 59 | M | 115 | 13 | 36.1 | 4.70 | 3,300 | 5.0 | 700 | Yes | S. pneumoniae | 117 | 96 | 31 |

| 4 | 48 | M | 80 | 9 | 36.4 | 4.57 | 3,000 | 7.0 | 2,000 | Yes | IFV A,1 galactomannan2 | 67 | 10 | 21 |

| 5 | 59 | M | 101 | 13 | 36.3 | 4.76 | 3,355 | 3.0 | 600 | Yes | IFV A,1 S. maltophilia3 | 222 | 36 | 29 |

| 6 | 46 | F | 134 | 10 | 36.4 | 4.11 | 3,930 | 4.5 | 600 | Yes | IVF A,1 C. pneumoniae4 | 217 | 14 | 32 |

| 7 | 54 | M | 102 | 15 | 36.3 | 5.31 | 3,600 | 7.5 | 500 | Yes | IVF A,2 S. haemolyticus,3 enterococcus5 | 128 | 131 | 29 |

| 8 | 69 | M | 100 | 4 | 36.9 | 4.55 | 3,200 | 4.0 | 1,600 | No | S. pneumoniae2 | 77 | 16 | 22 |

| 9 | 65 | F | 80 | 13 | 36.6 | 4.65 | 3,180 | 6.0 | 1,600 | Yes | S. pneumoniae2,4 | 129 | 24 | 20 |

| 10 | 48 | M | 115 | 13 | 36.8 | 4.40 | 3,200 | 6.5 | 1,500 | Yes | IVF A,1 A streptococcus3,4 | 353 | 90 | 16 |

| Median | 56 | 100.5 | 11.5 | 36.4 | 4.56 | 3,200 | 4.75 | 650 | 129 | 20.5 | 28 | |||

All data were registered on day 1. Abbreviations: SOFA score, sequential organ failure assessment score; LPM, liters per minute; RPM, revolutions per minute; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; F, female; M, male; IFV A, influenza A virus; S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae; galactomannan, aspergillus galactomannan; C. pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae; S. haemolyticus, Staphylococcus haemolyticus; A streptococcus, group A streptococcus.

Origins of the pathogens are indicated by superscript numbers: 1, sputum; 2, bronchoalveolar lavage; 3, respiratory secretions; 4, blood; 5, scrotal skin.

Pharmacokinetic modeling.

The parameters for the final PK model are shown in Table 2, together with uncertainties and distributions describing the interindividual variability (IIV) in model parameters. The plasma concentrations were best described by a two-compartment model with linear clearance. For incorporation of MD data, the concentration-time course in the peripheral compartment was found to describe the SCT observations well, with the free fraction in SCT estimated as a parameter (fu,tissue). Such a model, consisting of five parameters, could simultaneously describe the total meropenem concentration-time course in the central compartment (Ac/Vc; corresponding to plasma) and the free meropenem concentration-time course in the peripheral compartment [(Ap/Vp) × fu,tissue; corresponding to SCT]. Here, Ac and Ap correspond to the amount of drug in and Vc and Vp to the volumes of distribution of the central and peripheral compartments, respectively. Residual goodness-of-fit diagnostics are shown in Fig. 1 and a visual predictive check (VPC) is shown in Fig. 2, both demonstrating an acceptable fit of the model to the data.

TABLE 2.

Final parameter estimates and variances from the population analysis, including uncertainty and shrinkagea

| Parameter | Parameter description | Final model |

Reduced model |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | % RSE (% SHR) | Estimate | % RSE (% SHR) | ||

| CL (liters/h) | Elimination clearance | 3.09 | 11 | ||

| eCLCrb (ml/min) | Estimated creatinine clearance | 0.0460 | 6.7 | ||

| Vc (liters) | Central distribution vol | 8.31 | 9.0 | 8.19 | 8.5 |

| Q (liters/h) | Intercompartmental clearance | 8.52 | 31 | 9.34 | 28 |

| Vp (liters) | Peripheral distribution vol | 6.99 | 15 | 7.67 | 15 |

| fu | Fraction unbound in SCT | 0.790 | 4.6 | 0.782 | 4.2 |

| %CV | |||||

| CL | Variability in CL | 18.9 | 17 (0) | 33.6 | 17 (0) |

| Vc | Variability in Vc | 25.1 | 25 (7) | 24.8 | 24 (11) |

| Q | Variability in Q | 64.6 | 16 (6) | 72.8 | 23 (7) |

| ERR | Proportional residual error | 19.9 | 7.2 (4) | 21.4 | 11 (4) |

Abbreviations: %CV, percent coefficient of variation; RSE, relative standard error; SCT, subcutaneous adipose tissue; SHR, shrinkage.

eCLcr was determined using the Cockcroft-Gault formula.

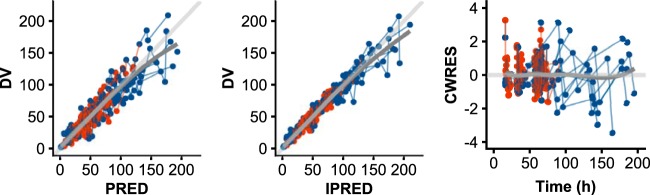

FIG 1.

Residual-based goodness-of-fit diagnostics based on the final model. From left to right are observations (DV) versus population predictions (PRED), observations (DV) versus individual predictions (IPRED), and conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) versus time. A line of identity (light gray) and a smooth to the points (dark gray) is shown for each subplot.

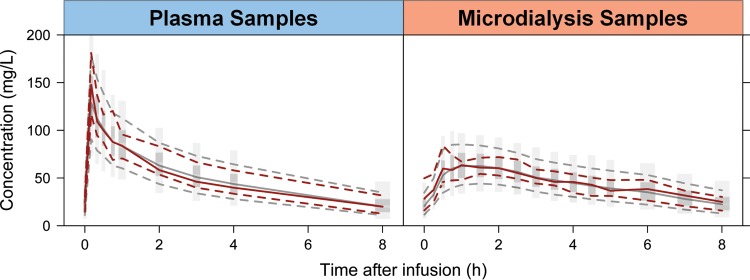

FIG 2.

Visual predictive check based on the final model. The red solid lines represent the median of the observations (plasma or microdialysis), and the red dashed lines represent the 90th and 10th outer percentiles of the observations. The shaded area is derived from simulations from the final model simulations, with the central dark-gray area representing a 95% confidence interval for the median and the light-gray areas representing the 95% confidence intervals for the 90th and 10th outer percentiles of the simulations.

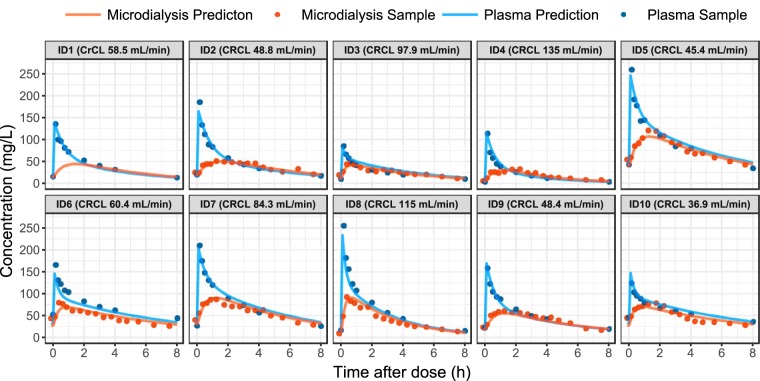

Differences between patients were described by including significant IIV terms on elimination clearance and central volume of distribution. When the MD samples were added to the model, differences between patients could also be identified by including an IIV term on the parameter describing intercompartmental clearance (Q). Inclusion of interoccassion variability (IOV) was found to be statistically significant when included on both elimination clearance and central volume of distribution (reduction in objective function values [OFV]). However, no IOV was included in the final model, because it led to overprediction of the observed variability when assessed by VPCs and did not result in obvious improvements in individual plots. The available samples from both plasma and SCT taken during the intensive sampling on day 1, as well as the individual patient predictions from the final model, are shown in Fig. 3. In general, SCT concentrations were lower than plasma concentrations, with peripheral area under the concentration-time curve (pAUC) being 21.5% lower than central AUC (cAUC) in all patients (equal to one minus the fu,tissue value).

FIG 3.

Overview of the samples (points) available from the intensive sampling on day 1 for each of the 10 individuals (with assayed microdialysis concentrations plotted at the midpoint of the collection interval). The predictions from the model are shown for both plasma and subcutaneous adipose tissue concentrations (solid lines). Note that individuals five, seven, and eight were administered 2 g of meropenem per dose, and that the baseline creatinine clearance is given for each patient.

For the covariate analysis, inclusion of estimated creatinine clearance (eCLCr) on elimination clearance improved the model fit (ΔOFV of 64.7) and reduced the associated random variability from 33 to 19% coefficient of variation (CV). The best implementation showed direct proportionality between clearance and eCLCr, as in CLi = CLfrac × eCLCri, where eCLCri is the individual eCLCr and CLfrac is an estimated parameter. Following this, the stepwise covariate model (SCM) procedure identified additional parameter-covariate relations, but these were not found to be statistically significant when assessing the actual significance level by use of randomization testing.

From the 10 patients' individual parameter estimates, the terminal half-lives as well as the AUC and Cmax (maximum concentration of drug in serum) values in both plasma and SCT were predicted for a dosing interval (1 g as a 5-min intravenous [i.v.] infusion) and are reported in Table 3. It is evident that the ratio of the peripheral unbound AUC to the plasma AUC is equal to the estimated fraction unbound in SCT (fu,tissue).

TABLE 3.

Derived variables following an 8-h dosing intervala (1-g dose as a 5-min i.v. infusion)

| ID | Sex | eCLCr (ml/min) |

fT>MIC (%) |

t1/2b (h) | AUCc (mg h/liter) |

Cmaxc (mg/liter) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | SCT | Central | Peripheral | Central | Peripheral | ||||

| 1 | M | 58.5 | 100 | 100 | 3.69 | 303.9 | 239.0 | 141.9 | 44.3 |

| 2 | M | 48.8 | 100 | 100 | 4.31 | 368.3 | 288.6 | 167.5 | 50.1 |

| 3 | F | 97.9 | 100 | 100 | 3.58 | 249.1 | 196.5 | 84.3 | 42.1 |

| 4 | F | 135.1 | 65.3 | 76.6 | 2.30 | 163.6 | 129.1 | 118.0 | 30.5 |

| 5 | F | 45.4 | 100 | 100 | 4.77 | 384.1 | 301.8 | 125.2 | 53.4 |

| 6 | M | 60.4 | 100 | 100 | 5.52 | 495.8 | 390.1 | 150.6 | 69.9 |

| 7 | F | 84.3 | 100 | 100 | 4.18 | 309.8 | 243.9 | 103.5 | 45.5 |

| 8 | F | 115 | 88.1 | 83.5 | 2.32 | 211.5 | 167.0 | 123.0 | 45.8 |

| 9 | M | 48.4 | 100 | 100 | 4.00 | 375.8 | 295.5 | 173.3 | 55.2 |

| 10 | F | 36.9 | 100 | 100 | 5.57 | 505.5 | 397.8 | 152.6 | 71.7 |

| Median | 4.09 | 339.0 | 266.2 | 133.5 | 48.0 | ||||

| IQR | 3.61, 4.66 | 262.8, 382.0 | 207.2, 300.2 | 119.3, 152.1 | 44.6, 54.7 | ||||

Drug was administered as a 1-g dose with a 5-min i.v. infusion. Abbreviations: ID, individual; F, female; M, male; eCLCr, estimated creatinine clearance calculated from the Cockgroft-Gault formula; fT, free time; SCT, subcutaneous adipose tissue; t1/2, terminal drug half-life; AUC, area under the concentration-time curve; Cmax, maximum concentration of drug in serum; IQR, interquartile range.

Calculated according to ln(2)/{0.5 × [(k12 + k21 + k10) − SQRT((k12 + k21 + k10)2 − 4 × k21 × k10)]}, where k12 = Q/Vc; k21 = Q/Vp; k10 = CL/Vc.

Derived using the differential equation solver in NONMEM for an 8-h dosing interval after two preceding doses according to 1 g q8h (i.e., calculation is for the time following the 1-g dose given at 16 h, with two previous doses given at 0 and 8 h).

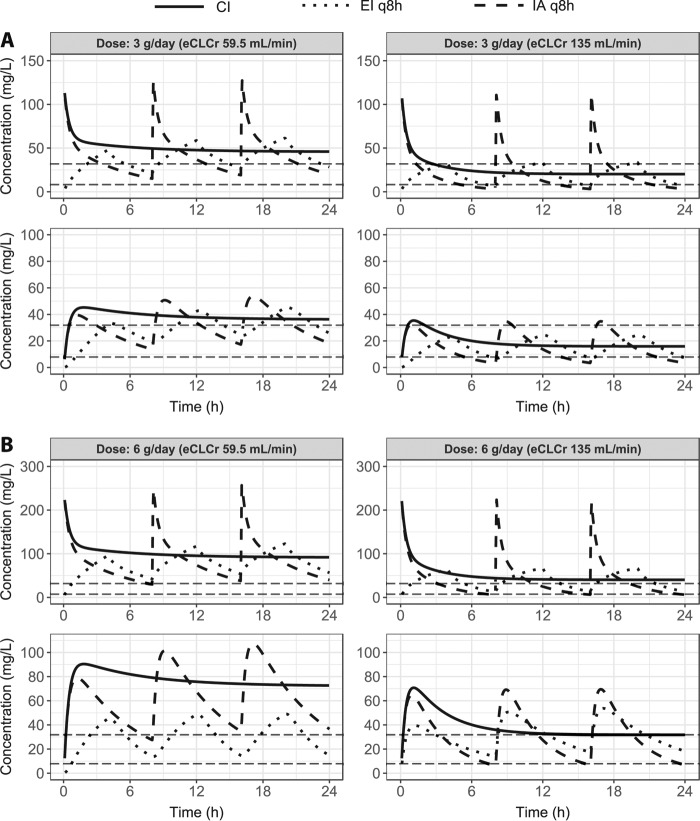

To illustrate the effect of renal function, predictions of meropenem 24-h PK profiles following intermittent administration (IA), extended infusion (EI), and continuous infusion (CI) administration were performed for a typical patient with either the median or highest observed eCLCr for total daily doses of 3 and 6 g (Fig. 4). For a patient with an eCLCr equal to the median eCLCr in the population, all investigated dosing regimens resulted in concentrations above the MIC (8 mg/liter) during the entire dosing interval. However, for a patient with an eCLCr equal to the highest observed eCLCr in the patient population with meropenem at 3 g a day given as IA and IE, concentrations were not maintained above the MIC (8 mg/liter) throughout the dosing interval.

FIG 4.

Model predictions of the time courses for three dosing regimens of meropenem with a total daily dose of 3 (A) or 6 (B) g. For each dose, the time courses are shown in plasma (top) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (bottom) for two typical patients who only differ in their value of estimated creatinine clearance (eCLCr) (median, 59.5 ml/min; highest observed, 135 ml/min). The horizontal dashed lines correspond to MICs of 8 and 32 mg/liter. Abbreviations: CI, continuous infusion; EI, extended infusion; IA, intermittent administration.

Simulations.

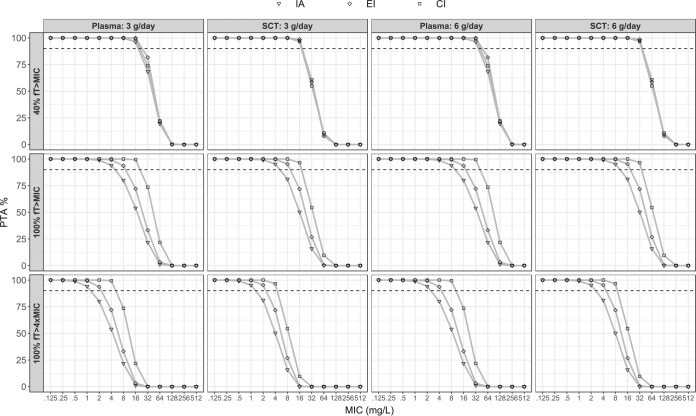

The probability of target attainment (PTA) curves that were constructed as a function of MIC are shown in Fig. 5 for a total daily dose of 3 and 6 g, respectively. To handle the included covariate effect, values of eCLCr were sampled from a distribution based on the included patients (median, 59.5 ml/min; standard deviation, 33.3; truncation at 20 and 180 ml/min). For the predefined target 40% fT>MIC, there was almost no difference in PTA between IA, EI, and CI. However, for the other two predefined targets (100% fT>MIC and 100% fT>4×MIC), EI and CI resulted in a higher PTA than IA. In addition to the curves, the PTA for a MIC of 8 mg/liter is included in Table 4 for the concentration-time course in both plasma and SCT. Furthermore, the exact MIC at which PTA is equal to 90% was derived to enable a numeric comparison among the different regimens.

FIG 5.

Probability of target attainment (PTA) for each of the three regimens using the final model and a distribution of estimated creatinine clearance (eCLCr) values. The graph indicates the PTA following the administration of 3 or 6 g per day for both plasma and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SCT) for a range of MICs. The dashed line indicates a PTA of 90%. Abbreviations: CI, continuous infusion; EI, extended infusion; IA, intermittent administration.

TABLE 4.

PTA for each of the six regimen for plasma and subcutaneous adipose tissuea

| Dosing regimen | PTA (%) for: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma |

SCT |

|||||

| 40% fT>MIC | 100% fT>MIC | 100% fT>4×MIC | 40% fT>MIC | 100% fT>MIC | 100% fT>4×MIC | |

| MIC of 8.0 mg/liter | ||||||

| IA 1 g q8h | 100 | 80.1 | 21.8 | 100 | 81.1 | 15.9 |

| IA 2 g q8h | 100 | 94.1 | 54.0 | 100 | 95.3 | 50.3 |

| EI 1 g q8h | 100 | 93.7 | 33.2 | 100 | 95.4 | 26.8 |

| EI 2 g q8h | 100 | 99.3 | 72.1 | 100 | 99.6 | 71.8 |

| CI 3 g/day | 100 | 100 | 73.5 | 100 | 100 | 54.5 |

| CI 6 g/day | 100 | 100 | 99.5 | 100 | 100 | 96.6 |

| MIC for predicted PTA of 90% | ||||||

| IA 1 g q8h | 21.0 | 5.3 | 1.3 | 21.0 | 5.7 | 1.4 |

| IA 2 g q8h | 42.0 | 10.5 | 2.6 | 41.9 | 11.4 | 2.8 |

| EI 1 g q8h | 28.1 | 9.6 | 2.4 | 21.4 | 10.3 | 2.6 |

| EI 2 g q8h | 56.1 | 19.3 | 4.8 | 43.0 | 20.6 | 5.1 |

| CI 3 g/day | 23.3 | 24.7 | 6.1 | 19.6 | 19.5 | 4.9 |

| CI 6 g/day | 49.6 | 49.4 | 12.3 | 39.2 | 38.9 | 9.7 |

The PTA were performed for a MIC value of 8.0 mg/liter and the MIC value at which the PTA is predicted to be 90% (bottom) for plasma and subcutaneous adipose tissue. Abbreviations: CI, continuous infusion; EI, extended infusion; IA, intermittent administration; fT, free time; PTA, probability of target attainment; SCT, subcutaneous adipose tissue.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the distribution of meropenem to both plasma and SCT in an ECMO patient population. Efficacious antimicrobial dosing in critically ill patients receiving ECMO treatment may be a significant challenge for the clinician. To address this problem, we performed this prospective observational study and developed a population PK model for meropenem PK in plasma and SCT in patients receiving ECMO treatment. Our results show that standard meropenem dosing of 1 g i.v. every 8 h (q8h) is likely to provide sufficient meropenem exposure to treat the problematic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa, given a 40% fT>MIC is sufficient. However, for patients with an increased eCLCr or if more aggressive targets, like 100% fT>MIC or 100% fT>4×MIC, are adopted, incremental dosing or CI may be needed. These findings are in agreement with Shekar et al. (22).

Since β-lactams are predominantly renally excreted, their concentration-time course is significantly influenced by renal function. Thus, a decrease in the eCLCr is associated with a decrease in β-lactam antimicrobial clearance (23). This makes eCLCr an important parameter for the treating clinician when choosing antimicrobial dosing, especially in situations where TDM is not available. This is in accordance with our results illustrated in Fig. 4. A decrease in eCLCr increases the likelihood of achieving 100% fT>MIC and 100% fT>4×MIC. The only two patients who failed to achieve 100% fT>MIC, even though one of them received 2 g meropenem q8h, had an eCLCr above 100 ml/min (Table 3). These results emphasize the need for incremental dosing or CI of meropenem to achieve 100% fT>MIC in patients with a high eCLCr.

Regarding covariates, the statistically significant identification of eCLCr on elimination clearance matches the knowledge of the renal elimination pathway for meropenem (as well as other β-lactams). Thus, while our identification of this relationship is unsurprising, it is important to realize that the eCLCr recorded in 9 of the 10 included patients is, to a certain extent, a reflection of the CRRT. As such, the proportionality between clearance and individual eCLCr should not be directly extrapolated or employed in settings other than that described in this study.

While a lower eCLCr does not guarantee therapeutic meropenem concentrations, it seems to be the most important factor. However, unknown biological variability factors may influence the unexplained IIV in antimicrobial concentrations. Therefore, TDM may be helpful to avoid suboptimal antimicrobial dosing and therapeutic failure. TDM is increasingly used worldwide and is a valuable tool to guide dose optimization in this complex group of critically ill patients. Accordingly, De Waele et al. illustrated that dose adaption of meropenem and piperacillin in critically ill patients, using TDM, increased the likelihood of PK/PD target attainment (24). Additionally, Roberts et al. demonstrated that dose adjustment following TDM was required in 74% of critically ill patients in order to optimize treatment with β-lactam antimicrobials (25). However, initial dosing was not adjusted according to patient eCLCr, which may partly explain the high percentage of patients in need of dose regulation. Because of the strong association between β-lactam concentrations and eCLCr, initial dosing adjusted to eCLCr could very well optimize dosing regimens early on.

The benefits of both prolonged infusion and incremental dosing are demonstrated in the results from the dosing simulations (Fig. 5 and Table 4). The probability of targeting 40% fT>MIC for a pathogen with a MIC of 8 mg/liter (clinical breakpoint MIC for P. aeruginosa) was 100% for all dosing regimens simulated in both plasma and SCT. However, the probability of targeting a concentration above 8 mg/liter throughout the dosing interval (100% fT>MIC) was above the accepted 90% level for meropenem (3 g per day) administered as EI and CI but not IA. A PTA above 90% for the predefined target 100% fT>4×MIC, which may be needed for maximum bactericidal activity in some patient populations, was only achieved for meropenem at 6 g per day, given as a CI.

In agreement with our findings, several studies have reported sustained concentrations above the MIC throughout the dosing interval and increased fT>MIC when administering β-lactam antimicrobials as prolonged infusions (17, 18, 26–28). The clinical benefits from CI are more pronounced when the infection is caused by a pathogen with reduced antimicrobial susceptibility and for patients with augmented clearance. However, no high-quality randomized controlled trials have been able to demonstrate a decrease in patient mortality when administering β-lactam antimicrobials as prolonged infusions (27, 29, 30). Nevertheless, Abdul-Aziz et al. demonstrated a higher clinical cure rate when administering β-lactam antimicrobials as CI (30). Furthermore, Roberts et al. have been able to show a decreased hospital mortality in a recently published meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomized trials (31).

One of the benefits with MD is that it selectively samples the unbound extracellular fraction of a drug in the ISF, which is considered to be the active part as most bacteria reside extracellularly (9). Furthermore, MD allows for serial sampling and provides high-resolution concentration-time profiles compared to other approaches, like biopsy procedures, which additionally do not allow for distinction between the intra- and extracellular compartments. Consequently, PK parameters obtained by MD are reliable and useful in the assessment of PK/PD targets, especially when the measurements are modeled similarly to how they are collected and not as the average over the collection interval. Our study has some limitations; for instance, our setup resulted in an RR of 18.5%. It is generally recommended that RR should exceed 20%, as lower levels of recovery are more exposed, with a magnification of the variation associated with the preanalytical sample handling and the chemical assay (32). The resulting variation will increase with a decrease in the RR. In our case we used the longest possible membrane (30 mm). Furthermore, we were obligated to meet the criteria of high temporal resolution due to the relatively short half-life of meropenem. Therefore, an RR of 18.5% seems acceptable.

A limitation of the study is the small study population of 10 patients, which is a small number on which to conduct a covariate analysis. However, the combinations of the intense and substantial sampling from plasma and SCT by MD are fully utilized by using a nonlinear mixed-effects modeling approach that relies on every observation from all individuals at once. Furthermore, a model-based approach allows for simultaneous incorporation and connection of measurements from different sampling sites and has the added benefit of handling the MD measurements in the way they are collected, i.e., a sample reflects the concentration over a time period and does not need to be treated as an average concentration over the collection interval in the analysis.

The analysis showed that meropenem followed two-compartment disposition kinetics and rapidly distributed into tissues, shown previously in both elderly with reduced renal function (33) and in patients with various degrees of obesity (Q of 9.92 and 15.9 liters/h, respectively) (34). Additionally, clearance (2.74 liters/h for a patient with median eCLCr of 59.5 ml/min), volume of distribution (15.3 liters), and half-life (4.09 h) are comparable to values of 3.19 liters/h, 18.0 liters, and 4.53 h, respectively, reported for patients treated by continuous hemodiafiltration (33).

Based on the collected data, the fraction of unbound meropenem in SCT was estimated to 0.79, a value close to the 0.721 reported in a previous study, where the probe was placed in the SCT of the abdominal wall (35). With the assumption that the plasma protein binding of meropenem is negligible (<2%) (33), the value can also be interpreted as the fraction of the plasma AUC following a dose that reaches the tissues and is unbound. This aspect is also reflected in Table 3, where the ratio of pAUC to cAUC is constant and equal to 0.79 (fraction unbound) for all included patients.

In conclusion, our results show that standard meropenem dosing of 1 g given i.v. q8h is likely to provide sufficient meropenem concentration to treat the problematic pathogen P. aeruginosa for patients receiving ECMO treatment when using the traditional target of 40% fT>MIC. However, for patients with an increased eCLCr or if more aggressive targets, like 100% fT>MIC or 100% fT>4×MIC, are adopted, dose increment or CI may be needed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

This was a prospective observational study conducted at the Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark, between February and May 2016. The study was approved by The National Committee on Health Research Ethics (registration number 1-16-02-312-15) and the Danish Health Authority (EudraCT number 2015-000218-23). The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and the ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP). The procedures of the study were monitored by the GCP unit at Aarhus and Aalborg University Hospital. Chemical analyses were performed at the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Aarhus University Hospital.

Patient population and study drug.

Aarhus University Hospital is the national veno-venous ECMO (VV-ECMO) center of Denmark, with 25 annual VV-ECMO runs and 75 veno-arterial ECMO (VA-ECMO) runs. Patients on ECMO treatment who were treated with meropenem were eligible for the study. All patients were sedated; thus, written informed consent was obtained from next of kin and the patient's general practitioner. ECMO treatment and treatment with meropenem were initiated less than 96 h prior to inclusion in the study. At day 1 all included patients had received a mean of 7 (range, 3 to 10) meropenem doses and had a mean ECMO treatment duration of 51.9 h (range, 20 to 69 h). The prior dosing history of meropenem was included in the data set. Patients under the age of 18 and patients who were pregnant were excluded from the study. The following data were registered for each enrolled patient: age, gender, weight, height, sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score on the day of inclusion, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelets, creatinine, carbamide, bilirubin, albumin, estimated creatinine clearance (eCLCr) derived from the Cockcroft-Gault formula (36), ECMO settings, positive blood and sputum cultures, and whether or not the patient was in dialysis treatment. Meropenem (1 or 2 g) was administered i.v. over 5 min every 8 h.

MD sampling was conducted over a single 8-h dosing interval. Meropenem clinical breakpoint MICs for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8 mg/liter), published by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (37), were used to evaluate the following PK/PD targets: 40% fT>MIC, 100% fT>MIC, and 100% fT>4×MIC. P. aeruginosa is a problematic pathogen in the intensive care unit environment, and the clinical breakpoint MIC reflects a worst-case scenario which needs to be considered when patients are treated empirically.

Microdialysis.

The MD probe was inserted in the SCT of the patients' upper arm 30 min prior to the ensuing meropenem dose. All probes were fixed to the skin with a single suture to prevent displacement. Briefly, MD is a probe-based technique that allows for diffusion of water-soluble molecules across a semipermeable membrane located at the tip of the probe (20, 21). Due to a continuous perfusion of the MD probe, equilibrium will never occur. Accordingly, the concentration of the dialysate will only represent a fraction of the actual concentration in the tissue. This fraction is referred to as relative recovery (RR) and can be determined by various calibration methods, which is imperative when evaluating absolute tissue concentration. In this study, cefuroxime was used as an internal calibrator for meropenem, thus no patient received cefuroxime prior to inclusion (38, 39). An in-depth description of MD can be found elsewhere (20, 21, 40–44).

In this study, equipment from μ-Dialysis AB (Stockholm, Sweden) was used. CMA 63 probes (membrane length of 30 mm with a 20-kDa cutoff) were used, and CMA 107 precision pumps produced a flow rate of 2 μl/min.

The RR of meropenem was calculated from the loss of the internal calibrator (cefuroxime) across the MD membrane based on the retrodialysis by calibrator methods (38). The following equation was used: meropenem RR (%) = 100 × (1 − Cout/Cin), where Cout is the cefuroxime concentration in the dialysate and Cin the cefuroxime concentration in the perfusate.

Meropenem concentrations were attributed to the midpoint of the sampling intervals in graphics. By correcting for the RR, the absolute tissue concentrations of meropenem (Ctissue) were calculated by the equation Ctissue = Cout/RR, where Cout is the determined meropenem concentration in the dialysate.

All catheters were calibrated individually.

Sampling procedures.

After placement of the MD probe in the upper arm, the MD system was perfused with 0.9% NaCl containing 5 μg/ml cefuroxime (provided by the Pharmacy at Aarhus University Hospital). Initially, a 30-min tissue calibration was allowed for. On the first day of sampling (day 1), blood and SCT samples were collected prior to the injection of meropenem (time zero). From time zero to 60 min, dialysates were collected during 15-min intervals, from time 60 to 300 min during 30-min intervals, and from time 300 to 480 during 60-min intervals. Blood samples were drawn from a peripheral arterial catheter at 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 120, 180, 240, and 480 min after administration of the drug. Furthermore, two blood samples were collected on days 2, 4, and 6 at 60 min and 480 min after the second meropenem dose administered that day.

The dialysates were instantly frozen on dry ice for a maximum of 9 h, after which they were transferred and stored at −80°C until analysis. Serum blood samples were kept at room temperature for a minimum of 30 min and a maximum of 90 min before being centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min. Serum aliquots were frozen and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Quantification of meropenem and cefuroxime concentrations.

Cefuroxime and meropenem in dialysates and serum were simultaneously analyzed with ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC). The UHPLC system consisted of an eluent pump, autosampler, and column compartment. A UV detector (Agilent 1290 Infinity; Agilent Technologies, USA) was equipped with a 1.7-μm-volume, 100- by 2.1-mm C18 column (Kinetex; Phenomenex, USA). For analysis of cefuroxime and meropenem in dialysates, 15 μl dialysate was mixed with 20 μl phosphate buffer, pH 3 (10 nM NaH2PO4, adjusted with HCl). After mixing, 5 μl was injected into the UHPLC system. Standards of 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 μg/ml cefuroxime and meropenem in 15 μl 0.9% NaCl were prepared and analyzed to prepare calibration curves for cefuroxime and meropenem. For this purpose, Chemstation software was used. Before analysis of meropenem in serum, 300 μl of serum was placed in an ultrafilter 96-well plate with a 30-kDa molecular mass cutoff (AcroPrep 30K Omega; Pall Corporation, USA) and centrifuged for 30 min at 1,000 × g, and then 15 μl of the filtrate was prepared for analysis as done for the dialysates. Cefuroxime and meropenem were separated on a C18 column at 40°C, with a gradient of acetonitrile in phosphate buffer (10 nM NaH2PO4, adjusted with HCl). The concentration of acetonitrile was elevated from 0% to 30% over a time span of 2.5 min, and the total time of analysis was 4 min with a postrun time of 1 min. Cefuroxime was detected at 275 nm, and meropenem was detected at 304 nm. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was found to be 0.5 μg/ml for quantification of meropenem and 0.06 μg/ml for quantification of cefuroxime. Interrun imprecisions (%CV) were 4.7% at 2.5 μg/ml for quantification of cefuroxime and 3.0% at 2.0 μg/ml for quantification of meropenem. The assays showed linearity in measurement response within 0.5 μg/ml to 105 μg/ml for meropenem and within 0.1 μg/ml to 130 μg/ml for cefuroxime. The accuracy for quantification of cefuroxime was found to be between −3.3% and 5.8%, and the accuracy for quantification of meropenem was found to be between −4.3% and 4.8%.

Pharmacokinetic modeling.

Based on the collected data, a population PK model was developed using NONMEM 7.3 (ICON Development Solutions, Hanover, MD, USA) (45), facilitated using Perl-Speaks-NONMEM and Piraña (46). The first-order conditional estimation method with interaction was used to estimate model parameters. Model evaluation and selection were based on goodness of fit and visual predictive checks (VPC) (47). The objective function values (OFV) of two nested models were used to compare the model fit using a likelihood ratio test and assuming that the OFV is χ2 distributed (a ΔOFV of 3.84 would be significant at a P value of 0.05 for one additional parameter).

Initially, a model was developed to describe the plasma observations by testing one- or two-compartment disposition models. Thereafter, the model was extended to incorporate the MD observations as described in Tunblad et al. (48). With this modeling approach, the data are the dialysate concentration at the end of a collection interval, reflecting the nature of how MD data are generated. We tested whether the MD data were optimally described by the meropenem concentration-time course in the central, peripheral, or a separate compartment. Furthermore, it was assumed that the protein binding of meropenem in plasma was negligible (previously shown in patients on hemodiafiltration) (49). To describe variability among patients, interindividual variability (IIV) terms were included when significant, assuming log-normally distributed parameters. Furthermore, as the study included samples from multiple days, interoccasion variability (IOV) was tested on both clearance and volume parameters.

Following a good description of the data, patient covariates were tested to explain part of the observed random variability. From the available covariates, the primary focus was on testing eCLCr on the elimination parameter, since meropenem is known to be primarily renally excreted and weight on PK parameters is in line with the allometric principle. Parameter-covariate relations were included as linear relationships for continuous covariates [1 + θi × (Xi − Xmedian), where θi is the estimated covariate effect, Xi is the individual covariate value, and Xmedian is the median covariate value in the population], except for weight, which was allometrically scaled. Categorical covariates were included as a shift in the typical value for the least common category. Due to the small size of the data set and relatively dense sampling, randomization testing was performed before inclusion of any covariate to assess the actual significance level (50). The potential explanatory value of gender, age, albumin, and dialysis was also examined using a stepwise covariate model (SCM) (51).

From a final established population PK model, the following metrics were derived for each of the included patients based on an 8-h dosing interval: fT>MIC, the plasma and SCT areas under the concentration-time curves (cAUC/pAUC), tissue penetration ratio, terminal half-life (t1/2), and peak plasma and SCT drug concentration (central Cmax/peripheral Cmax).

Simulations.

Based on the developed model, a number of predictions and simulations were done. First, to assess alternative dosing regimens, the typical 24-h meropenem concentration-time course in plasma and SCT was predicted following intermittent administration (IA), extended infusion (EI), and continuous infusion (CI). The IA dosing regimen consisted of 1 and 2 g q8h, the EI dosing regimen of 1 and 2 g q8h (infusion over 4 h), and the CI dosing regimen of 3 and 6 g infused over 24 h with a loading dose of 1 or 2 g, respectively. At the intensive care unit at Aarhus University Hospital, it is standard practice to initiate continuous meropenem infusion with a loading dose of 1 or 2 g with the purpose of achieving therapeutic concentrations immediately. After the loading dose has been given, continuous meropenem infusion is started right away, and the steady-state concentration due to the infusion is assumed to be achieved rapidly, as the extra meropenem from the initial bolus is eliminated due to the short half-life of meropenem. Second, the probability of target attainment (PTA) for these six dosing regimens was assessed for the following predefined targets: 40% fT>MIC, 100% fT>MIC, and 100% fT>4×MIC. This assessment was done by constructing curves based on 100,000 simulated patients. The PTA was calculated for a dosing interval under steady-state conditions for each of the three regimens. For parameter-covariate relationships identified and included in the final model, the covariate values were sampled from a distribution when constructing the PTA curves instead of relying on the point values from the included patients. Furthermore, SCT simulations reflected the predicted free concentration in the tissue over time rather than concentrations in a collection interval.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine, Aarhus University Hospital, for supporting this study. Also, we thank all of the patients and families that participated in the study.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartlett RH, Gattinoni L. 2010. Current status of extracorporeal life support (ECMO) for cardiopulmonary failure. Minerva Anestesiol 76:534–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraser J, Shekar K, Diab S, Dunster K, Foley S, McDonald C, Passmore M, Simonova G, Roberts J, Platts D. 2012. ECMO–the clinician's view. ISBT Sci Ser 7:82–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2824.2012.01560.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacLaren G. 2011. Evidence and experience in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Chest 139:965–966. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacLaren G. 2012. Lessons in advanced extracorporeal life support. Crit Care Med 40:2729–2731. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825ae6dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shekar K, Fraser JF, Smith MT, Roberts JA. 2012. Pharmacokinetic changes in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Crit Care 27:741.e9-18. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shekar K, Roberts JA, Ghassabian S, Mullany DV, Wallis SC, Smith MT, Fraser JF. 2013. Altered antibiotic pharmacokinetics during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: cause for concern? J Antimicrob Chemother 68:726–727. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shekar K, Roberts JA, Ghassabian S, Mullany DV, Ziegenfuss M, Smith MT, Fung YL, Fraser JF. 2012. Sedation during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-why more is less. Anaesth Intensive Care 40:1067–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shekar K, Roberts JA, Mullany DV, Corley A, Fisquet S, Bull TN, Barnett AG, Fraser JF. 2012. Increased sedation requirements in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory and cardiorespiratory failure. Anaesth Intensive Care 40:648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drusano GL. 2004. Antimicrobial pharmacodynamics: critical interactions of “bug and drug.” Nat Rev Microbiol 2:289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kristoffersson AN, David-Pierson P, Parrott NJ, Kuhlmann O, Lave T, Friberg LE, Nielsen EI. 2016. Simulation-based evaluation of PK/PD indices for meropenem across patient groups and experimental designs. Pharm Res 33:1115–1125. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-1856-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li C, Du X, Kuti JL, Nicolau DP. 2007. Clinical pharmacodynamics of meropenem in patients with lower respiratory tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:1725–1730. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00294-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinnon PS, Paladino JA, Schentag JJ. 2008. Evaluation of area under the inhibitory curve (AUIC) and time above the minimum inhibitory concentration (T>MIC) as predictors of outcome for cefepime and ceftazidime in serious bacterial infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 31:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tam VH, McKinnon PS, Akins RL, Rybak MJ, Drusano GL. 2002. Pharmacodynamics of cefepime in patients with Gram-negative infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 50:425–428. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi Y, Lipman J, Udy AA, Ng M, McWhinney B, Ungerer J, Lust K, Roberts JA. 2013. Beta-lactam therapeutic drug monitoring in the critically ill: optimising drug exposure in patients with fluctuating renal function and hypoalbuminaemia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 41:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huttner A, Harbarth S, Hope WW, Lipman J, Roberts JA. 2015. Therapeutic drug monitoring of the beta-lactam antibiotics: what is the evidence and which patients should we be using it for? J Antimicrob Chemother 70:3178–3183. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joukhadar C, Frossard M, Mayer BX, Brunner M, Klein N, Siostrzonek P, Eichler HG, Muller M. 2001. Impaired target site penetration of beta-lactams may account for therapeutic failure in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 29:385–391. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts JA, Kirkpatrick CM, Roberts MS, Robertson TA, Dalley AJ, Lipman J. 2009. Meropenem dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis and without renal dysfunction: intermittent bolus versus continuous administration? Monte Carlo dosing simulations and subcutaneous tissue distribution. J Antimicrob Chemother 64:142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts JA, Roberts MS, Robertson TA, Dalley AJ, Lipman J. 2009. Piperacillin penetration into tissue of critically ill patients with sepsis–bolus versus continuous administration? Crit Care Med 37:926–933. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181968e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller M, dela Pena A, Derendorf H. 2004. Issues in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of anti-infective agents: distribution in tissue. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:1441–1453. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1441-1453.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joukhadar C, Muller M. 2005. Microdialysis: current applications in clinical pharmacokinetic studies and its potential role in the future. Clin Pharmacokinet 44:895–913. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller M. 2002. Science, medicine, and the future: microdialysis. BMJ 324:588–591. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7337.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shekar K, Fraser JF, Taccone FS, Welch S, Wallis SC, Mullany DV, Lipman J, Roberts JA. 2014. The combined effects of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and renal replacement therapy on meropenem pharmacokinetics: a matched cohort study. Crit Care 18:565. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0565-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blot S, Lipman J, Roberts DM, Roberts JA. 2014. The influence of acute kidney injury on antimicrobial dosing in critically ill patients: are dose reductions always necessary? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 79:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Waele JJ, Carrette S, Carlier M, Stove V, Boelens J, Claeys G, Leroux-Roels I, Hoste E, Depuydt P, Decruyenaere J, Verstraete AG. 2014. Therapeutic drug monitoring-based dose optimisation of piperacillin and meropenem: a randomised controlled trial. Intensive Care Med 40:380–387. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts JA, Ulldemolins M, Roberts MS, McWhinney B, Ungerer J, Paterson DL, Lipman J. 2010. Therapeutic drug monitoring of beta-lactams in critically ill patients: proof of concept. Int J Antimicrob Agents 36:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts JA, Kirkpatrick CM, Roberts MS, Dalley AJ, Lipman J. 2010. First-dose and steady-state population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of piperacillin by continuous or intermittent dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dulhunty JM, Roberts JA, Davis JS, Webb SA, Bellomo R, Gomersall C, Shirwadkar C, Eastwood GM, Myburgh J, Paterson DL, Lipman J. 2013. Continuous infusion of beta-lactam antibiotics in severe sepsis: a multicenter double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 56:236–244. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdul-Aziz MH, Lipman J, Akova M, Bassetti M, De Waele JJ, Dimopoulos G, Dulhunty J, Kaukonen KM, Koulenti D, Martin C, Montravers P, Rello J, Rhodes A, Starr T, Wallis SC, Roberts JA. 2016. Is prolonged infusion of piperacillin/tazobactam and meropenem in critically ill patients associated with improved pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic and patient outcomes? An observation from the Defining Antibiotic Levels in Intensive care unit patients (DALI) cohort J Antimicrob Chemother 71:196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dulhunty JM, Roberts JA, Davis JS, Webb SA, Bellomo R, Gomersall C, Shirwadkar C, Eastwood GM, Myburgh J, Paterson DL, Starr T, Paul SK, Lipman J. 2015. A multicenter randomized trial of continuous versus intermittent beta-lactam infusion in severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 192:1298–1305. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0857OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdul-Aziz MH, Sulaiman H, Mat-Nor MB, Rai V, Wong KK, Hasan MS, Abd Rahman AN, Jamal JA, Wallis SC, Lipman J, Staatz CE, Roberts JA. 2016. Beta-lactam infusion in severe sepsis (BLISS): a prospective, two-centre, open-labelled randomised controlled trial of continuous versus intermittent beta-lactam infusion in critically ill patients with severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med 42:1535–1545. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts JA, Abdul-Aziz MH, Davis JS, Dulhunty JM, Cotta MO, Myburgh J, Bellomo R, Lipman J. 2016. Continuous versus intermittent beta-lactam infusion in severe sepsis. A meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomized trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 194:681–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaurasia CS, Muller M, Bashaw ED, Benfeldt E, Bolinder J, Bullock R, Bungay PM, DeLange EC, Derendorf H, Elmquist WF, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Joukhadar C, Kellogg DL Jr, Lunte CE, Nordstrom CH, Rollema H, Sawchuk RJ, Cheung BW, Shah VP, Stahle L, Ungerstedt U, Welty DF, Yeo H. 2007. AAPS-FDA Workshop White Paper: microdialysis principles, application, and regulatory perspectives. J Clin Pharmacol 47:589–603. doi: 10.1177/0091270006299091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Usman M, Frey OR, Hempel G. 2017. Population pharmacokinetics of meropenem in elderly patients: dosing simulations based on renal function. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 73:333–342. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung EK, Cheatham SC, Fleming MR, Healy DP, Kays MB. 2017. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of meropenem in nonobese, obese, and morbidly obese patients. J Clin Pharmacol 57:356–368. doi: 10.1002/jcph.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wittau M, Scheele J, Kurlbaum M, Brockschmidt C, Wolf AM, Hemper E, Henne-Bruns D, Bulitta JB. 2015. Population pharmacokinetics and target attainment of meropenem in plasma and tissue of morbidly obese patients after laparoscopic intraperitoneal surgery. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6241–6247. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00259-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. 1976. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.EUCAST. 2017. Clinical breakpoints. http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/ Accessed 11 October 2017.

- 38.Bouw MR, Hammarlund-Udenaes M. 1998. Methodological aspects of the use of a calibrator in in vivo microdialysis-further development of the retrodialysis method. Pharm Res 15:1673–1679. doi: 10.1023/A:1011992125204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varghese JM, Jarrett P, Wallis SC, Boots RJ, Kirkpatrick CM, Lipman J, Roberts JA. 2015. Are interstitial fluid concentrations of meropenem equivalent to plasma concentrations in critically ill patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy? J Antimicrob Chemother 70:528–533. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bue M, Birke-Sorensen H, Thillemann TM, Hardlei TF, Soballe K, Tottrup M. 2015. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in porcine cancellous and cortical bone determined by microdialysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 46:434–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanberg P, Bue M, Birke Sorensen H, Soballe K, Tottrup M. 2016. Pharmacokinetics of single-dose cefuroxime in porcine intervertebral disc and vertebral cancellous bone determined by microdialysis. Spine J 16:432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tøttrup M, Bibby BM, Hardlei TF, Bue M, Kerrn-Jespersen S, Fuursted K, Soballe K, Birke-Sorensen H. 2015. Continuous versus short-term infusion of cefuroxime: assessment of concept based on plasma, subcutaneous tissue, and bone pharmacokinetics in an animal model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:67–75. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03857-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tøttrup M, Bue M, Koch J, Jensen LK, Hanberg P, Aalbaek B, Fuursted K, Jensen HE, Soballe K. 2016. Effects of implant-associated osteomyelitis on cefuroxime bone pharmacokinetics: assessment in a porcine model. J Bone Joint Surg Am 98:363–369. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tøttrup M, Hardlei TF, Bendtsen M, Bue M, Brock B, Fuursted K, Soballe K, Birke-Sorensen H. 2014. Pharmacokinetics of cefuroxime in porcine cortical and cancellous bone determined by microdialysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3200–3205. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02438-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boeckmann AJ, Sheiner LB, Beal S, Bauer RJ. 2013. NONMEM user's guides (1989-2013). ICON Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keizer RJ, Karlsson MO, Hooker A. 2013. Modeling and simulation workbench for NONMEM: tutorial on Pirana, PsN, and Xpose CPT. Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 2:e50. doi: 10.1038/psp.2013.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bergstrand M, Hooker AC, Wallin JE, Karlsson MO. 2011. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed-effects models. AAPS J 13:143–151. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tunblad K, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Jonsson EN. 2004. An integrated model for the analysis of pharmacokinetic data from microdialysis experiments. Pharm Res 21:1698–1707. doi: 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000041468.00587.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krueger WA, Schroeder TH, Hutchison M, Hoffmann E, Dieterich HJ, Heininger A, Erley C, Wehrle A, Unertl K. 1998. Pharmacokinetics of meropenem in critically ill patients with acute renal failure treated by continuous hemodiafiltration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:2421–2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wahlby U, Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO. 2001. Assessment of actual significance levels for covariate effects in NONMEM. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 28:231–252. doi: 10.1023/A:1011527125570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO. 1998. Automated covariate model building within NONMEM. Pharm Res 15:1463–1468. doi: 10.1023/A:1011970125687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]