Abstract

Objectives

During 2010–2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention implemented the National Public Health Improvement Initiative (NPHII) to assist 73 public health agencies in conducting activities to increase accreditation readiness, improve efficiency and effectiveness through quality improvement, and increase performance management capacity. A summative evaluation of NPHII was conducted to examine whether awardees met the initiative’s objectives, including increasing readiness for accreditation.

Design

A nonexperimental, utilization-focused evaluation with a multistrand, sequential mixed-methods approach was conducted to monitor awardee accomplishments and activities. Data analysis included descriptive statistics, as well as subanalyses of data by awardee characteristics. Thematic analysis using deductive a priori codes was used for qualitative analysis.

Results

Ninety percent of awardees reported completing at least 1 accreditation prerequisite during NPHII, and more than half reported completing all 3 prerequisites by the end of the program. Three-fourths of awardees that completed a self-assessment reported closing gaps for at least 1 Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) standard. Within 3 years of the launch of PHAB accreditation, 7 NPHII awardees were accredited; another 38 had formally applied for accreditation.

Conclusions

Through NPHII, awardees increased collaborative efforts around accreditation readiness, accelerated time-lines for preparing for accreditation, and prioritized the completion of required accreditation activities.

Keywords: accreditation, program evaluation, public health organization and administration

With support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) launched the voluntary national public health accreditation program in September 2011. This historic launch followed significant field-driven efforts in exploring, designing, and testing a process for accrediting health departments.1 The first health departments were accredited in 2013, and, as of early 2017, more than 400 health departments were either accredited or had formally applied to PHAB for accreditation.2 PHAB accreditation enables public health agencies to measure and improve their performance against national standards and demonstrate accountability, credibility, and improved health outcomes.3–5 PHAB accreditation is based on standards and measures grounded in the 10 Essential Public Health Services and built on the foundations of continuous quality improvement (QI) and performance management, concepts that had been advanced in public health during the last 2 decades.1,6–9

Building on momentum to improve public health infrastructure, CDC launched the National Public Health Improvement Initiative (NPHII) in 2010. Funded through the Prevention and Public Health Fund of the Affordable Care Act, NPHII provided financial and technical resources to 73 state, tribal, local, and territorial public health agencies to conduct activities that supported the following:

Increased efficiency: Saving time or money on program services and operations;

Increased effectiveness: Using practices that have been shown to work or making services and programs available to more people; and

Accreditation readiness: Completing projects to prepare for application to PHAB for national accreditation.3

Over the program’s 4 years, awardees received a total of $142 million.10 As with any new initiative, the focus of NPHII programmatic activities evolved over time. Throughout the program’s duration, there was a general focus on performance improvement, including the requirement to hire or designate a performance improvement manager with the responsibility of fostering organizational QI.10 By the fourth and final year, NPHII awardees were expected to implement relevant and essential activities to accelerate the agency’s accreditation readiness, advance their ability to meet or conform with the national PHAB standards, identify and implement 2 or more performance improvement or QI initiatives, and continue performance management activities.

Specifically, the program guidance outlined activities to increase accreditation readiness, including completing an organizational self-assessment against the PHAB standards and developing or making progress toward developing at least one of the 3 PHAB accreditation prerequisites (a state/tribal/community health assessment, a state/tribal/community health improvement plan, and an agency-wide strategic plan). Additional activities included completion of 1 or more of the following: (1) planning for accreditation, including developing a timeline and roadmap to guide the agency’s PHAB accreditation application; (2) organizing the agency workforce and documentation for accreditation; and (3) engaging in QI activities tied to addressing a deficiency that relates to a specified PHAB standard or measure.10

In addition to programmatic guidance, CDC funded several national capacity-building assistance (CBA) partners* to provide technical assistance (TA), tools, and support to awardees to assist with the completion of NPHII activities.5 These national partners developed resources and provided training accessible to all awardees and the public health community at large (eg, guidebooks, webinars). These same organizations provided direct TA or training—often onsite—to individual awardees upon request. In addition, a learning community of key staff—referred to as the Performance Improvement Managers Network (PIM Network)—was created to foster peer sharing and support.

Methods

Data collection

The nonexperimental NPHII evaluation applied a utilization-focused, multistrand, sequential mixed-methods approach to examine whether awardees met the initiative’s objectives, including increasing readiness for accreditation. Two primary data sources were used to analyze accreditation readiness activities—program progress reports and key informant interviews (KIIs).

Program progress reports

To monitor awardees’ accomplishments and activities, NPHII awardees were required to submit interim and annual progress reports (IPRs and APRs, respectively) each program year. The progress reports captured awardee progress toward achievement of NPHII objectives, including completion of activities that would advance their ability to meet or conform to the national PHAB standards.

Year 4 APR (ie, final APR) incorporated questions for both evaluation and programmatic purposes. Awardees were asked to indicate their organization’s status in completing each of the prerequisites and, if completed, the date of completion and the degree to which NPHII support or funds were used to support the development of the prerequisite (fully, partially, or not at all). Awardees were also asked to report activities undertaken to increase readiness for accreditation, indicate their status in participating in the PHAB program, and the type of accreditation readiness support they provided to other health agencies. Finally, the final APR included an Impact and Sustainability section with questions designed to increase CDC’s understanding of the scope of accomplishments and outcomes observed by the awardees, NPHII’s impact on awardees’ capacity to achieve programmatic objectives, and awardees’ plans to sustain NPHII-related activities.10

For the last 2 years of the program (NPHII years 3 and 4), awardees were required to complete an organizational self-assessment against the PHAB standards. The annual progress reports from the third and fourth years of the program asked awardees to report whether they had completed or updated the self-assessment and to evaluate their cumulative progress in meeting each PHAB standard. The progress reports listed the PHAB standards, which are organized into 12 domains; the first 10 domains address the 10 Essential Public Health Services. Domain 11 addresses management and administration, and Domain 12 addresses governance.6 There are 2 to 4 standards in each domain; awardees were asked to self-assess against each standard and indicate whether the standard was met, whether a gap was identified, and whether the awardee was in process of addressing the gap or not yet addressing the gap. As a reference during the self-assessment process, awardees could access the approved Standards and Measures documents on PHAB’s Web site, which give greater detail for each standard such as measures and documentation guidance.7

The NPHII program ended on September 30, 2014. Sixty-two awardees carried over their NPHII funds and continued activities after that date, not to exceed September 30, 2015. The final APR was due 90 days after the program’s end. As of December 30, 2014, 68 of 73 awardees submitted final APRs.† Unless otherwise noted, all data included in this article represent the status of awardee activity at the end of the NPHII program, as reported in the final APR.

Key informant interviews‡

From August to October 2014, staff members from ICF Macro, an ICF International Inc company (hereafter referred to as ICF), conducted KIIs with 55 NPHII stakeholders. Interviews were conducted with individuals from 21 awardee sites representing diverse perspectives, including top agency officials or health directors, other senior leaders (eg, deputy directors), and senior program leaders who might have interacted with NPHII (eg, chronic disease director). Nine interviews were conducted with select NPHII-funded national CBA partners and thought leaders in the fields of public health accreditation, performance management, and QI who were also familiar with NPHII. During the 60-minute telephone interviews, participants were asked to describe their experience with NPHII and their perception of its impact, particularly which aspects were most valuable, any unintended consequences or unanticipated benefits of the initiative, and sustainability of initiatives once funding ended.

Data analysis

Data analysis included simple descriptive statistics, as well as subanalyses of data by awardee characteristics of interest identified a priori. In the last year of the program, NPHII funded 73 public health agencies/organizations (48 states, the District of Columbia, and 9 local, 8 territorial, and 7 tribal agencies/organizations). While sample sizes were small for some agency types, there were some notable differences across findings. Throughout the “Results” section, data are reported in the aggregate. If meaningful variation was identified, specifically by awardee agency/organization type, then cross-tabulations are shared.

Colleagues from ICF conducted qualitative analysis of responses to the Impact and Sustainability section of the final APR and KIIs to identify themes, patterns, and interrelationships. For each set of data, Atlas.ti version 7.0 qualitative data management software was used to conduct a thematic analysis using a deductive set of a priori codes. Prior to independent coding, the team of 3 analysts reached 80% intercoder reliability across all coders. Throughout analysis, team members met regularly to discuss any questionable code assignments and worked to achieve group consensus before including newly emergent or further refined codes in the analysis.

Results

Achievement of accreditation

In final program reporting at the initiative’s end in 2014, 7 awardees (5 states and 2 local awardees) achieved accreditation (Table).§ According to respondents, more than one-third of awardees (34%) submitted an application for accreditation and 8% submitted a statement of intent to pursue accreditation. Only 1 awardee reported its organization decided not to apply. Two of the 9 local awardees achieved accreditation, 4 submitted an application, and one of the remaining 2 local awardees submitted a statement of intent to pursue accreditation. Although none of the 7 territorial awardees reported submitting an application or statement of intent to pursue accreditation, 43% planned to apply for accreditation. In qualitative interviews, awardees among all agency types reported that the ability to use NPHII funds to pay the accreditation fee was instrumental in their ability to apply for accreditation; this is not surprising, given that identification of funding sources for fees is a well-documented challenge for health departments.11,12

TABLE.

Awardee Accreditation Status

| Accreditation Status | Total (N = 67) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Organization has achieved accreditation | 7 | 10.4 |

| Organization has submitted application for accreditation | 23 | 34.3 |

| Organization has submitted a statement of intent to pursue accreditation | 5 | 7.5 |

| Organization plans to apply for accreditation but has not submitted a letter of intent yet | 19 | 28.4 |

| Organization has not decided whether to apply for accreditation | 12 | 17.9 |

| Organization has decided not to apply for accreditation | 1 | 1.5 |

Accreditation readiness activities

During the final year of NPHII, 97% of nonaccredited awardees (n = 58/60) reported completing activities to advance their readiness for accreditation. The most commonly reported activities included conducting communications or meetings with leadership (71.7%; n = 43) or staff (58.3%; n = 35), designating or maintaining individual(s) to coordinate accreditation readiness activities (55.0%; n = 33), and organizing agency documentation for accreditation (51.7%; n = 31). The activities reported least commonly were completing the PHAB online orientation (25.0%; n = 15) and developing a roadmap for the agency’s application to PHAB’s accreditation program (21.7%; n = 13). Of the nonaccredited awardees that reported completing accreditation readiness activities in the last year of the program, all awardees reported that these were fully or partially funded/supported by NPHII (n 58). Awardees also reported that TA provided by national partner agencies, informally through the PIM Network, or through hands-on training and learning communities, was crucial to strengthening the awardees’ ability to complete accreditation readiness activities.10

Findings from analysis of qualitative data from the final APR suggest NPHII funding of readiness activities provided the necessary financial and technical support that enabled leaders to make these efforts a priority within their agencies. Furthermore, completion of accreditation readiness activities helped awardees better understand agency operations, encourage cross-bureau work, and collaborate with external partners in new and better ways.

PHAB prerequisites

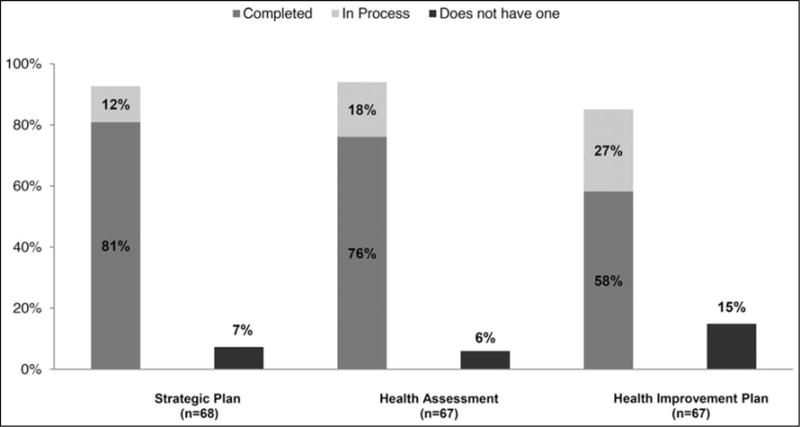

Figure 1 shows the completion status of each PHAB prerequisite by the end of NPHII. Awardees most frequently reported completion of an organization-wide strategic plan (81%), followed by a health assessment (76%) and health improvement plan (58%). Half of tribal and territorial health departments, 87% of state awardees, and 78% of local awardees developed a strategic plan during NPHII. In general, a larger percentage of local and state (100% and 89.3%, respectively) awardees reported completion of prerequisites compared with territorial or tribal awardees (85.7% and 80.0%, respectively).

FIGURE 1. Completion Status of Each PHAB Accreditation Prerequisite by the End of NPHII Year 4.

Abbreviations: NPHII, National Public Health Improvement Initiative; PHAB, Public Health Accreditation Board.

By the end of NPHII, 54% of NPHII awardees (n = 36/67) reported completing all 3 PHAB accreditation prerequisites within the past 5 years (the PHAB-required time frame), an increase from 28% of awardees in October 2009.¶ Of the awardees that completed all 3 prerequisites, 61% (n = 22) fully/partially used NPHII funding and/or support to establish all 3 accreditation prerequisites. Ninety percent (n = 61) of NPHII awardees reported completing or updating 1 or more PHAB prerequisites during NPHII. Of these awardees, 89% (n = 54) fully/partially used NPHII funding and/or support to establish or update 1 or more PHAB prerequisite.

Figure 2 shows awardee progress in completing the accreditation prerequisites between May 2013 and December 2014.

FIGURE 2. Awardee Progress in Completing NPHII Prerequisites, May 2013-December 2014 (n = 67).

Abbreviations: APR, annual progress report; IPR, interim progress report; NPHII, National Public Health Improvement Initiative.

Organizational self-assessment against PHAB domains and standards

Eighty-six percent of awardees (n = 62) reported completing an organizational self-assessment against PHAB standards during the final 2 years of NPHII. More than three-fourths of awardees reported closing gaps against at least 1 PHAB standard, making gains in moving from not working on a standard to addressing it or from addressing a standard to meeting a standard (77.4%; n = 48). Of the 4 tribal awardees that completed an organizational self-assessment, all closed gap(s) for at least 1 standard.

The PHAB standards that were most often reported as met by awardees were standard 4.1 (engage with the community to identify and address health problems), standard 3.1 (provide health education and health promotion policies, programs, processes, and interventions to support prevention and wellness), and standard 11.2 (establish effective financial management systems).

The standards with the most gaps reported were standard 9.1 (use a performance management system to monitor achievement of organizational objectives), standard 8.2 (assess staff competencies and address gaps by enabling organizational and individual training and development opportunities), and standard 9.2 (develop and implement QI processes integrated into organizational practice, programs, processes, and interventions). While fewer awardees reported meeting these standards, many were in the progress of closing gaps against the standards (50%, 48%, and 44%, respectively).

Support for other health agencies

Half of the awardees (n = 34/68) used part of their year 4 NPHII funding to support accreditation readiness of other territorial, tribal, or local public health agencies (eg, local health departments [LHDs] within a state’s jurisdiction). These awardees included 31 state, 2 territorial, and 1 tribal agencies/organizations. Forty-seven percent of awardees (n = 32) provided training or TA to 697 health agencies for accreditation readiness, including support for conferences and workshops, as well as support for collaboration with hospitals on community health needs assessments. Forty-six percent of awardees (n = 31) used NPHII funds to provide approximately $1.5 million for subawards and other types of financial support to 199 health agencies. For several state health departments, the subawards funded by NPHII were used by LHDs to complete community health assessments and/or provide trainings to increase capacity at the county level.

Findings from KIIs‖

The vast majority of health department leaders from NPHII-funded agencies across all agency types described NPHII as invaluable to their ability to pursue and achieve accreditation, which was commonly reported as a key achievement across funded agencies. Several awardee agency leaders from state and LHDs emphasized that the focus on accreditation provided the impetus for their agency to prioritize the completion of all of the required activities for achievement of PHAB accreditation and make these activities the norm within their agencies, which would have been much more challenging without NPHII.

NPHII support also helped many awardees overcome challenges and barriers associated with implementing accreditation readiness activities. More specifically, NPHII funding provided these public health agencies with the resources they needed to dedicate time and energy to complete necessary tasks to increase accreditation readiness. NPHII also helped them overcome challenges related to engaging local partners such as logistical barriers and resistance to participation in community health planning activities.

Furthermore, many agency leaders reported that NPHII funding helped them complete the PHAB prerequisites. Respondents mentioned how completion of health assessments, health improvement plans, and strategic plans helped increase their understanding of their target audiences’ health needs. Some state program leaders also specified that the focus on health assessment early on in the funding period helped inform the development of their state health improvement plans.

Many respondents also reported on their ability to conduct more rigorous reviews of data to inform agency priorities and track progress on strategic planning goals and objectives. These accreditation readiness activities helped awardees better align public health work within and across their states’ various public health agencies. In particular, state health department leaders noted that increased engagement in strategic planning efforts across divisions allowed multiple parts of the agency to take ownership of the goals, objectives, strategies, and activities defined within the plan and recognize the specific expertise that each department brought to the table.

Most awardee respondents that already planned to apply for accreditation mentioned that NPHII funding accelerated timelines and processes by providing staffing support to spearhead accreditation readiness activities. For agencies that did not originally pursue accreditation, because they lacked either leadership support or resources, state agency and program leaders reported that NPHII provided the necessary financial and technical support needed to prioritize accreditation readiness activities.10 Overall, leaders across all agency types expressed a high level of confidence in their increased ability to apply for and/or achieve accreditation. While this confidence was not directly attributed to NPHII, respondents discussed the fact that successful efforts to complete accreditation readiness activities better prepared them to apply for and achieve accreditation.

Discussion

NPHII advanced awardees’ accreditation readiness in several ways. By the end of the program, almost all awardees had engaged in accreditation readiness activities, such as developing PHAB prerequisites, conducting self-assessments against the PHAB standards and making progress toward closing identified gaps, and providing support to other health agencies to engage in similar activities. NPHII support, either financially or through multiple TA mechanisms, was vital for awardees’ ability to complete these activities.10

NPHII awardees made strides in completing the accreditation prerequisites, with 90% reporting completion of at least 1 prerequisite during NPHII and more than 50% reporting completion of all prerequisites by the end of the program. Given that the community health improvement plan must be done on the basis of the community health assessment, which impacts the timeline for completion, it is not surprising that the community health improvement plan has one of the lowest reported rates of completion.13

NPHII also helped agencies become more effective in identifying organizational gaps and weaknesses and completing targeted QI projects.10 Three-fourths of awardees that completed a self-assessment reported closing gaps for at least 1 PHAB standard. Of those standards that were least frequently met, all are among the most cited challenges in preparing for accreditation.10,14 Two of these standards (9.1 and 9.2) are directly related to NPHII activities explicitly stated in the NPHII program guidance. For both standards, nearly 90% of awardees reported either meeting those standards or making progress toward meeting those standards. Of the 3 standards that were most often met, it is likely that those were also standards for which public health agencies were already doing a good job before NPHII.15

NPHII also accelerated timelines for preparing for accreditation. Within 3 years of the launch of PHAB accreditation, 7 NPHII awardees had been accredited and another 38 had entered the accreditation process by submitting an application or statement of intent to apply. Awardees’ ability to use NPHII funds to pay for the accreditation fee also helped address a documented barrier to application.10

One benefit of NPHII was the reach of NPHII support beyond the direct awardees. NPHII helped increase awardees’ capacity to coordinate with, train, and provide financial and nonfinancial supports to other public health agencies, such as LHDs within their jurisdiction. Thirty-five awardees used NPHII year 4 funding to support other health agencies, and of those awardees, 97% provided support related to accreditation readiness. Among states that used NPHII funds to support other agencies for accreditation readiness, 17% of LHDs became accredited or began the formal accreditation process in e-PHAB, PHAB’s online information system. In comparison, among the states that did not use NPHII funds for local support, only 7% of the LHDs were accredited or in the accreditation process.**

According to thought leader KII respondents, NPHII supported progress within public health for accreditation. These respondents noted that this momentum might not have been possible without NPHII, and they expressed a strong appreciation for NPHII in making accreditation readiness a more prominent goal among more public health agencies across the country.

Limitations

All data were self-reported, including the organizational self-assessment against the PHAB standards, and there were limited opportunities for validation of the data. In addition, awardee understanding of the field of accreditation readiness evolved during the program as PHAB finalized its standards and measures and launched national voluntary accreditation, whereas other partners played roles in developing tools to advance readiness efforts. As a result, awardee understanding of the PHAB accreditation process changed over time, and changes in responses to accreditation readiness questions might be attributable to this improved understanding rather than an increase or decrease in related activities.

Implications for Policy & Practice.

-

■

NPHII awardees achieved many successes in implementing and completing accreditation readiness activities. NPHII’s unique and innovative approach allowed awardees to choose how they used financial and TA to implement relevant and essential activities to accelerate their agency’s accreditation readiness. As a result, awardees increased collaborative efforts around accreditation readiness, accelerated time-lines for preparing for accreditation, and prioritized the completion of required activities for accreditation.

-

■

NPHII also served as a catalyst for elevating accreditation to a high priority achievement, both nationally and within awardee agencies, and increased agencies’ capacity to mitigate challenges in achieving accreditation as they arose.10

-

■

Findings from this evaluation demonstrate the benefit of and need for systematic, comprehensive, and flexible approaches to building readiness for accreditation within public health agencies.

Acknowledgments

The evaluation of the National Public Health Improvement Initiative (NPHII) is funded through a cooperative agreement (5U8HM000520) between the National Network of Public Health Institutes (NNPHI) and the Office for State, Tribal, Local and Territorial Support at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The authors thank Anita McLees, Andrea Young, and Craig Thomas from CDC, for their guidance and support to evaluate NPHII, and Laura Hsu, for her support in cleaning and validating the quantitative data. The authors also thank the following staff from ICF International for their contributions to the design, analysis, and reporting of qualitative findings included in this article: Tamara Lamia, Kari Cruz, Dara Schlueter, Shilin Zhou, and Mary Ann Hall.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The methods descriptions and findings presented from qualitative data collection and analysis were informed by reports produced solely for the purposes of the NPHII evaluation. Information from the following reports was used with permission from the authors:

Lamia T, Cruz K, Schlueter D, Zhou S. National Public Health Improvement Initiative Summative Evaluation Interview Summary Report. Unpublished report; 2015.

Lamia T, Cruz K, Schlueter D. Qualitative Findings From Select Questions in the 2014 Annual Progress Reports. Unpublished report; 2015.

The NPHII-funded national partner organizations included the American Public Health Association, Association of American Indian Physicians, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, National Association for County & City Health Officials, National Network of Public Health Institutes, and Public Health Foundation.

The 62 awardees that carried over NPHII funds were asked to submit a year 4 APR by December 30, 2014. Those awardees also have the option of submitting a revised final APR once their carryover activities are completed.

T. Lamia, K. Cruz, D. Schlueter, S. Zhou (unpublished data, 2015).

At the end of NPHII year 5 (September 30, 2014), the following agencies reported achieving accreditation: Chicago, Houston, Minnesota, New York State, Oklahoma, Vermont, and Washington. As of May 2017, 29 awardees had achieved accreditation—20 states, the District of Columbia, and 1 tribe and 7 locals.

Within the past 5 years refers to prerequisites completed after October 2010. Analysis excludes awardees with missing observations at one or both points in time (n = 5).

T. Lamia, K. Cruz, D. Schlueter, S. Zhou (unpublished data, 2015).

The remaining states either did not report on this question or were excluded because of the nature of their LHD infrastructure. Internal data analysis conducted by PHAB and CDC using e-PHAB and NPHII data, July 2015.

Contributor Information

Nikki Rider, National Network of Public Health Institutes, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Cassandra M. Frazier, Applied Systems Research and Evaluation Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, Georgia.

Sarah McKasson, National Network of Public Health Institutes, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Liza Corso, Office for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Support, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, Georgia.

Jennifer McKeever, National Network of Public Health Institutes, New Orleans, Louisiana.

References

- 1.Riley W, Bender K, Lownick E. Public health department accreditation implementation: transforming public health department performance. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):237–242. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Health Accreditation Board. Accredited health departments. http://www.phaboard.org/news-room/accredited-health-departments. Accessed May 1, 2017.

- 3.Public Health Accreditation Board. Accreditation overview. http://www.phaboard.org/accreditation-overview/. Accessed May 1, 2017.

- 4.Riley WJ, Lownik EM, Scutchfield FD, Mays GP, Corso LC, Beitsch LM. Public health department accreditation: setting the research agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas C, Pietz H, Corso L, Erlwein B, Monroe J. Advancing accreditation through the National Public Health Improvement Initiative. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(1):36–38. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182a8a5cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thielen L. Exploring public health experience with standards and accreditation. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Published October 2004. http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/ephli/resources/exploring_public_health.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corso LC, Lenaway D, Beitsch LM, Landrum LB, Deutsch H. The national public health performance standards: driving quality improvement in public health systems. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(1):19–23. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181c02800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health Accreditation Board. Public health department accreditation background. http://www.phaboard.org/about-phab/public-health-accreditation-background/. Accessed July 6, 2015.

- 9.Kronstadt J, Meit M, Siegfried A, Nicolaus T, Bender K, Corso L. Evaluating the impact of national public health department accreditation—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:803–806. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6531a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advancing Public Health: the Story of the National Public Health Improvement Initiative. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/stltpublichealth/docs/nphii/Compendium.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Theilen L. To Be or Not to Be: Accredited. A Study of Incentives to Promote Public Health Accreditation. Arlington, VA: National Association of County & City Health Officials; http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/accreditation/upload/To-Be-or-Not-To-Be_Incentives-Paper-doc.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis M, Cannon M, Corso L, Lenaway D, Baker L. Incentives to encourage participation in the national public health accreditation model: a systematic investigation. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1706–1711. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Public Health Accreditation Board. Tips for getting started. http://www.phaboard.org/accreditation-overview/getting-started. Updated September 23, 2015. Accessed September 23, 2015.

- 14.Bender K, Kronstadt J, Wilcox R, Tilson H. Public health accreditation addresses issues facing the public health workforce. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(5 suppl 3):S346–S351. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NORC at the University of Chicago. Brief Report: Evaluation of the Public Health Accreditation Board Beta Test. Chicago, IL: NORC at the University of Chicago; 2011. http://www.phaboard.org/wp-content/uploads/EvaluationofthePHABBetaTestBriefReportAugust2011.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]