Abstract

Objectives

To describe self-reported stress level, cognitive appraisal and coping among patients with heart failure (HF), and to examine the association of cognitive appraisal and coping strategies with event-free survival.

Methods

This was a prospective, longitudinal, descriptive study of patients with chronic HF. Assessment of stress, cognitive appraisal, and coping was performed using Perceived Stress Scale, Cognitive Appraisal Health Scale, and Brief COPE scale, respectively. The event-free survival was defined as cardiac rehospitalization and all-cause death.

Results

A total of 88 HF patients (mean age 58 ± 13 years and 53.4% male) participated. Linear and cox regression showed that harm/loss cognitive appraisal was associated with avoidant emotional coping (β= −0.28; 95% CI: −0.21 – 0.02; p= 0.02) and event free survival (HR= 0.53; 95% CI: 0.28 – 1.02; p= 0.05).

Conclusions

The cognitive appraisal of the stressors related to HF may lead to negative coping strategies that are associated with worse event-free survival.

Keywords: Stress, Cognitive Appraisal, Coping, Heart Failure, Event-Free Survival

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a costly condition with high mortality and morbidity rates.1,2 In 2012, the total costs for HF in the United States were approximately $31 billion, and this amount will rise to approximately $70 billion by 2030.3 Although biological factors contribute to the high morbidity and mortality in HF, there are many unexplored psychosocial factors that potentially contribute to poor prognosis.4,5

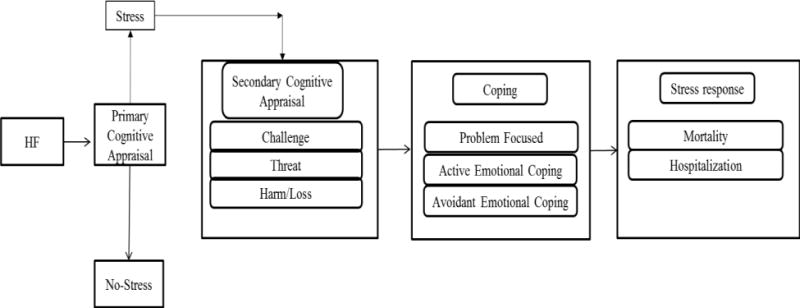

Heart failure is commonly perceived with considerable psychological distress.6–10 Based on the work Lazarus and Folkman as well as others’ in the literature,4,6–22 we developed a model of HF patients’ response to stressors (Figure 1). In this model, HF is the stressor. Stressors have been defined as environmental circumstances or chronic conditions that are appraised in a primary appraisal process, and then are seen as either benign or a threat to physical and/or psychological health or well-being.23 In those with HF, cognitive appraisal is the patient’s perception of an event or situation, their assessment of the degree to which the event is stressful, and their perception of the potential impact of the event on personal goals and resources.22,24 People have considerable differences in their appraisal of and response to stressors.25 Thus, cognitive appraisal is a core component of this as well as other stress models.22,26 Stressors can be appraised primarily as: (1) irrelevant when the situation has no effect on the individual, (2) benign positive when the situation is evaluated as positive, or (3) or stressful.22 When appraised as stressful, the stressor can be further appraised (secondary appraisal) as: (1) harm/loss resulting in damage to self or social esteem; (2) threat, which refers to a suspected pain; or (3) challenge, which allows for the opportunity for gain and growth.22 Cognitive appraisal has been shown to play an important role in determining the impact of the stress response.15 Specifically, appraisal of a stressor in the harm/loss or threat categories result in poor health outcomes, impaired performance and lower quality of life.14,16 In contrast, appraisal as a challenge has been associated with positive effects on cardiovascular reactivity and task engagement.14,16

Figure 1.

Heart Failure Patients’ Response to stressors

Cognitive appraisal of HF can predict psychological and physical coping responses.27 Lazarus and Folkman (1984) defined coping as “Constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” while attempting to manage, master, or alter the stressful situation by reducing or tolerating it.21,28 The following two major types of coping have been suggested: emotion-focused and problem focused.22

Emotion-focused coping is an attempt to control emotional response to a stressful situation when individuals believe they cannot change the situation.29 These strategies can be divided into active emotional coping and avoidant emotional coping.17,18 Active emotional coping includes venting, positive reframing, humor, acceptance, and emotional support strategies. Avoidant emotional coping includes self-distraction, denial, behavioral disengagement, self-blame, and substance use.19,20 The predominant view of emotion-focused coping is that it is a maladaptive form of coping associated with impaired health outcomes. Emotion-focused coping is associated with unhealthy lifestyle practices such as smoking, lack of exercise, drinking, non-compliance with medical regimen, and drug use that may lead to frequent hospitalization and even higher mortality rate.30,31 In contrast, problem-focused coping consists of cognitive and behavioral strategies to alter or manage the stressor, such as planning, reaching out for instrumental support, and religion.19,20 These are positively associated with better adjustment and health outcomes such as longer survival and fewer hospitalization compared to those with emotion-focused coping.31

Understanding factors that affect survival in patients with HF is important to design future interventions to reduce the stress from HF and change how HF patients appraise their condition and cope with it. The purposes of this study were to describe self-reported stress level, cognitive appraisal and coping among patients with HF, and to examine the association of cognitive appraisal and coping strategies with event-free survival.

Methods

Design, sample, and setting

A prospective, longitudinal, descriptive design was used in which patients’ follow up were performed for 6 months to determine the occurrence of the endpoint of time to re-hospitalization for cardiac causes or death from any cause. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board. A convenience sample of 88 patients with HF who were hospitalized for cardiac reasons at an academic health care center and a level 1 trauma medical center in Kentucky, USA was used in this study.

Patients with a diagnosis of chronic HF were eligible for participation in the study if they were: 1) admitted to the hospital with a primary or secondary diagnosis of exacerbation of chronic HF or any other cardiac diagnosis; 2) 21 years or older; 3) able to read and speak English; and 4) not obviously cognitively impaired. Cognitive impairment was defined as the presence of a diagnosis of dementia or cognitive impairment, the inability of the patient to provide informed consent, or to provide an accurate description of what was expected in the study after the study was explained by research staff. Chronic HF was defined as an existing and confirmed diagnosis of HF from a cardiologist. Only patients with existing HF (versus new onset) were considered to have chronic HF. Patients were excluded from the study for: 1) co-existing terminal illness likely to be fatal within 6 months; 2) presence of a left ventricular assist device, continuous inotropic infusion, or hospice care; 3) active suicidality (defined as choosing option 2 or 3 on item 9 of the Beck Depression Inventory-II); 4) history of the death of a spouse or child within the past month; 5) history of psychotic illness or bipolar illness; or 6) current alcohol dependence or other substance abuse.

Power analysis was performed using G-Power 3.1 with power level of 0.80, level of significance of 0.05, the medium effect size of 0.15, and seven predictors. A minimum sample size of 103 was recommended based on the G-Power analysis.

Variables and Measures

Stress

Stress was measured using the brief version of the Perceived Stress Scale.32 This version consists of a four-item scale that has been demonstrated to be reliable and valid,32 in a variety of countries and in multiple populations including those with chronic illness.33,34 Each item was rated by patients on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (very often). Higher scores indicate greater levels of stress. Cronbach’s alpha for this instrument in the current study was 0.71. The four items were: (1) how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?, (2) how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems?, (3) how often have you felt that things were going your way?, and (4) how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?

Cognitive Appraisal

Cognitive appraisal types (Challenge, Threat, and Harm/Loss) were measured using the brief version of the Cognitive Appraisal Health Scale.35,36 This version contains 13 items derived from Kessler’s scale, which is one of the most commonly used measures of cognitive appraisal of stressful and non-stressful events.24 Validity was supported by component factor analysis and reliability has been shown in previous studies.35,36 The responses in this scale range from 0 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Higher scores indicate that the patient does not commonly use that type of appraisal. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.78.

Coping

Coping was measured using the Brief COPE scale.37 This 28-item scale is an abbreviated version of the COPE Inventory.37 The reliability and validity of the brief COPE have been demonstrated in multiple patient populations, and used in those with chronic conditions and with HF.37,38 The responses to items on this scale range from 1 (I haven’t been doing this at all) to 4 (I have been doing this a lot). Based on conceptual and empirical literature the 14-subscales were grouped in three coping strategies which are active emotional coping, avoidant emotional coping, and problem focused coping.12,22,39 Higher scores on the subscales indicate that the patient commonly used that coping strategy. The Cronbach’s alpha for the COPE in this study was 0.78.

Event-free survival

Event-free survival was defined as the combined endpoint of cardiac hospitalization or all-cause death. Hospitalization data were determined through a combination of patient and family interviews and a review of medical records. Hospitalizations were verified and documented by trained research assistants who reviewed medical records and clinic notes on a weekly basis. Given the possibility that patients could have been hospitalized at different facilities, trained research assistants carefully questioned the patients or family members by phone to determine if hospitalization had occurred elsewhere.

All-cause death was determined by reviewing medical records and contacting the patient’s family. At enrollment, the patient was asked for contact information for a close friend or family member in case the patient could not be contacted. At follow-up if a patient could not be reached by phone, hospital records were searched. When information regarding the patient was not available, family members or friends were contacted.

Demographic and clinical variables

These variables included age, gender, ethnicity, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. NYHA class indicated the level of functional impairment reported by patients as a result of symptoms. These variables were selected because of their effects on the outcome as suggested in the literature.40,41

Procedure

Hospitalized patients were identified by clinicians and referred to research staff who determined each patient’s eligibility. The study and its voluntary nature were thoroughly explained to each patient and signed informed consent was obtained after answering any questions patients had about the study. The research staff met with the patients to administer study questionnaires via the web based Survey Monkey. The questionnaires took approximately 20 minutes to complete. A paper copy was offered to the patient if they did not feel comfortable with the web based survey.

Patients were contacted by phone at two weeks, three months, and six months from hospital discharge. At each telephone contact, the research staff asked the patient whether he or she has been hospitalized or visited the emergency unit. At the end of the study period, hospital records were reviewed to confirm deaths, re-hospitalizations or emergency department visits.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations and frequency distributions, were used to describe sample characteristics. Two tailed Pearson correlation coefficients were used to determine bivariate relationship among the variables. Multiple linear regressions were used to determine the association between stress and cognitive appraisal type, stress and coping style, and cognitive appraisal and coping style. Age, gender, and NYHA class were controlled in those three multiple linear regressions. Two groups, low and high perceived stress level, were created based on the median of perceived stress level and used in this analysis. The median was used to create the groups because there are no published cut-points to define high and low stress levels.

To examine the association of cognitive appraisal and coping strategies with event-free survival (cardiac hospitalization or all-cause death), adjusted Cox regression analysis (survival analysis) was used to determine whether different types of cognitive appraisal and coping styles, independently predict event-free survival. Each type of cognitive appraisal (Challenge, Threat, and Harm/Loss) and each style of coping (Problem focused coping, Active emotional coping, and Avoidant emotional coping) was entered in separate Cox regression analysis to predict event-free survival. The following covariates were considered in the adjusted analyses: age, gender, and NYHA class. The assumptions of all Cox regressions and multiple linear regressions were tested for violations, and none were noted. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients (N = 88) are summarized in Table 1. The average stress score in this sample was 9.44 ± 3.86, with a range of 4 to 20. The average cognitive appraisals scores were as following: threat appraisal 2.46 ± 0.87, challenge appraisal 2.47 ± 0.77, and harm/loss appraisal 2.65 ± 0.88. The average coping styles scores were as follows: problem-focused coping 2.82 ± 0.66, active-emotional coping 2.57± 0.56, and avoidant-emotional coping 1.56 ± 0.38. A total of 29 (32.9%) patients had an event: seven (7.9%) died and 22 (25%) were hospitalized for cardiac reasons.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N = 88)

| Characteristic | N (%) OR MEAN ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 58.13 ± 12.64 |

| Stress Score | 9.44 ± 3.86 |

| Cognitive appraisal | |

| Threat Score | 2.46 ± 0.87 |

| Challenge Score | 2.47 ± 0.77 |

| Harm/Loss Score | 2.65 ± 0.88 |

| Coping Style | |

| Problem Focused Coping Score | 2.82 ± 0.66 |

| Active Emotional Coping Score | 2.57± 0.56 |

| Avoidant Emotional Coping Score | 1.56 ± 0.38 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 47 (53.4) |

| Female | 41 (46.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 68 (77.3) |

| African American | 20 (22.7) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 47 (53.4) |

| Married or cohabitate | 41 (46.6) |

| Education Level | |

| High school or under | 50 (56.8) |

| Higher than high school | 38 (43.2) |

| Employment Status | 59 (67.0) |

| Unemployed | 29 (33.0) |

| Employed | |

| NYHA class | |

| I/II | 40 (45.5) |

| III/IV | 48 (54.5) |

| Stress | |

| Not Stressed | 47 (53.4) |

| Stressed | 41 (46.6) |

Note: NYHA = New York Heart Association, SD = standard deviation.

The two tailed Pearson correlations showed that harm/loss cognitive appraisal was significantly correlated with stress level (r= −0.342, p = 0.005). Specifically, higher levels of stress were associated with the more common use of harm/loss appraisal. Stress level was also significantly correlated with avoidant emotional coping (r= 0.429, p < 0.001). The avoidant emotional coping style was associated with higher levels of stress. In addition, threat cognitive appraisal was significantly correlated with avoidant emotional coping (r= −0.372, p = 0.002). Furthermore, harm/loss cognitive appraisal was significantly correlated with the avoidant emotional coping (r= −0.433, p < 0.001).

In adjusted analyses, and with regard to prediction of cognitive appraisal, multiple linear regressions showed that none of the demographic, clinical, or stress variables was a significant predictor of challenge (Table 2). The only significant predictors of cognitive appraisal as threat were age (β 0.39; 95% CI: 0.01 – 0.04; p = 0.01) and gender (β −0.23; 95% CI: −0.81–0.01; p = 0.05). Specifically, older age and female gender were associated with cognitive appraisal as a threat. Finally, age (β 0.06; 95% CI: −0.01 – 0.02; p = 0.05) and stress (β −0.37; 95% CI: −1.11 – 0.23; p < 0.001) were the only significant predictors of cognitive appraisal as harm/loss. Specifically, older age and higher stress level were associated with harm/loss cognitive appraisal.

Table 2.

Predictors of the Cognitive Appraisal Type Based on the Stress Level (Multiple Linear Regression)

| Variable | β | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Challenge Cognitive Appraisal | |||

| Age | 0.06 | −0.01 – 0.02 | 0.68 |

| Female Gender | 0.08 | −0.29 – 0.52 | 0.57 |

| NYHA class III/IV compared to I/II | −0.18 | −0.70 – 0.13 | 0.18 |

| High stress level compared to low stress level | 0.13 | −0.21 – 0.62 | 0.32 |

| Overall Model (Adjusted R2 = −0.02, F=0.665; P= 0.619) | |||

| Threat Cognitive Appraisal | |||

| Age | 0.39 | 0.01 – 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Female Gender | −0.23 | −0.81 – 0.01 | 0.05 |

| NYHA class III/IV compared to I/II | 0.24 | 0.01 – 0.83 | 0.46 |

| High stress level compared to low stress level | −0.06 | −0.52 – 0.31 | 0.61 |

| Overall Model (Adjusted R2 = 0.215, F=5.173; P= 0.001) | |||

| Harm/loss Cognitive Appraisal | |||

| Age | 0.06 | −0.01 – 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Female Gender | 0.01 | −0.42 – 0.46 | 0.91 |

| NYHA class III/IV compared to I/II | 0.20 | −0.09 – 0.81 | 0.12 |

| High stress level compared to low stress level | −0.37 | −1.11 – −0.23 | <0.001 |

| Overall Model (Adjusted R2 = 0.126, F=3.190; P= 0.020) | |||

Note: CI = confidence interval, β = adjusted regression slope coefficient, NYHA = New York Heart Association

Significant predictors of avoidant emotional coping included harm/loss cognitive appraisal (β −0.28; 95% CI: −0.21 – −0.02; p = 0.02) and stress level (β 0.30; 95% CI: 0.04 – 0.38; p = 0.02); controlling for age, gender, and NYHA class (Table 3). Higher levels of stress and greater use of harm/loss cognitive appraisal were associated with avoidant emotional coping style.

Table 3.

Predictors of the Avoidant Emotional Coping of Patients with Heart Failure Based on the Cognitive Appraisal Type (Multiple Linear Regression)

| Variable | β | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.15 | −0.01 – 0.00 | 0.20 |

| Female Gender | 0.13 | −0.10 – 0.25 | 0.25 |

| NYHA class III/IV compared to I/II | −0.15 | −0.27 – 0.06 | 0.19 |

| High stress level compared to low stress level | 0.30 | 0.04 – 0.38 | 0.02 |

| Harm/loss cognitive appraisal | −0.28 | −0.21 – 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Threat cognitive appraisal | −0.15 | −0.12 – 0.06 | 0.30 |

| Challenge cognitive appraisal | −0.05 | −0.14 – 0.10 | 0.72 |

| Overall Model (Adjusted R2 = 0.26, F=5.425; P< 0.001) | |||

Note: CI = confidence interval, β = adjusted regression slope coefficient, NYHA = New Yor Heart Association

In analyses adjusted for age, gender and NYHA class, where cognitive appraisal types were the independent variables, none of the demographics, clinical characteristics, or cognitive appraisal variables was significant predictors of event-free survival (Table 4). Where coping styles were the independent variables, none of the demographics, clinical characteristics or coping styles were significant predictors (Table 5).

Table 4.

Predictors of the Cardiac Event-free Survival Based on the Cognitive Appraisal Type (Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Regression)

| Predictor Variables | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 | 0.98 – 1.06 | 0.35 |

| Female Gender | 0.84 | 0.32 – 2.24 | 0.73 |

| NYHA class III/IV compared to I/II | 0.86 | 0.33 – 2.23 | 0.76 |

| Harm/loss cognitive appraisal | 0.53 | 0.28 – 1.02 | 0.05 |

| Threat cognitive appraisal | 0.89 | 0.49 – 1.60 | 0.69 |

| Challenge cognitive appraisal | 1.14 | 0.59 – 2.18 | 0.70 |

| Overall Model (χ2 = 7.56, df = 7; p =0.48) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, NYHA = New York Heart Association

Table 5.

Predictors of the Cardiac Event-free Survival Based on the Coping Style (Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Regression)

| Predictor Variables | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 | 0.98 – 1.07 | 0.37 |

| Female Gender | 0.76 | 0.31 – 1.83 | 0.54 |

| NYHA class III/IV compared to I/II | 0.74 | 0.29 – 1.87 | 0.52 |

| Problem Focused Coping | 1.98 | 0.92 – 4.25 | 0.08 |

| Active Emotional Coping | 0.91 | 0.39 – 2.11 | 0.83 |

| Avoidant Emotional Coping | 3.23 | 1.14 – 9.16 | 0.03 |

| Overall Model (χ2 = 7.97, df = 6; p =0.24) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, NYHA = New York Heart Association

Discussion

Despite the medical and surgical advances in HF treatment, mortality and morbidity rates are still substantial even in comparison to some aggressive types of cancer.42–45 We hypothesized the relationships among the study variables (stress, cognitive appraisal, and coping) depicted in the model (Figure 1) that was developed based on the literature to date.

In this study, we investigated whether cognitive appraisal type predicted 6-month event-free survival. Our findings suggest that greater use of harm/loss cognitive appraisal predicted shorter event-free survival in HF. None of the other cognitive appraisal types were significant predictors. These findings suggest that threat and harm/loss cognitive appraisals may lead to negative coping styles such as avoidant emotional coping that also predicted shorter event-free survival in the unadjusted model. This result can be explained by the association of the harm/loss cognitive appraisal with other negative psychosocial factors such as depression and anxiety that been found to short event free survival among HF patients.46,47 Healthcare providers must assist patients to learn and use more positive types of appraisal and coping in response to stress. Cognitive behavioral therapy is effective in assisting patients assume healthier appraisal and coping strategies, which are associated with better health outcomes, greater self-efficacy, and less depression and anxiety.48,49

We found also that higher stress levels were associated with greater use of harm/loss cognitive appraisal. This finding suggests that patients with HF respond negatively to higher stress levels with an appraisal type that is associated with negative health outcomes, and are unable to marshal a positive coping response to stress. Other healthy and chronically ill subjects have demonstrated the ability to respond to the stress imposed by their condition with a healthier type of cognitive appraisal, challenge, which is associated with better adherence and outcomes.14,15

In a study conducted among patients with the human immunodeficiency virus, psychological stress was associated with threat cognitive appraisal.50 Our findings suggest that HF patients may have a different appraisal for the stressful situation since a higher level of stress was associated with harm/loss cognitive appraisal. However, these findings demonstrate that cognitive appraisal plays a role in the stress response.15

In our study, only stress and harm/loss cognitive appraisal were predictors of avoidant emotional coping style. Our findings suggest that higher levels of stress and greater use of harm/loss cognitive appraisal were associated with the avoidant emotional coping style. Thus, the dominant type of cognitive appraisal in our sample of patients with HF is associated with a coping style that has negative health outcomes and a negative impact on emotional well-being. Similar findings have been reported in the literature.51–55

Our study was the first to investigate stress, cognitive appraisal, coping, and event-free survival in HF patients. Many of our findings were consistent with other investigations conducted on different groups of healthy and ill subjects.50,56–58 However, our findings did not support all the relationship in the hypothesized model. A potential explanation is that the measures did not adequately capture stress and coping styles. We used brief stress and coping scales that contains 4 and 28 items respectively. Both shortened measures have been demonstrated to be valid and reliable; nonetheless, the full instruments may have provided more complete information about stress level, and coping styles than the shorter versions.32,37,59,60 Another potential explanation is that the 6 month follow up period may have been too short to capture the effect of coping styles on the health outcomes in patients with HF. Also, the role of the culture in response to stress and coping style may have affected our results. The sample was recruited from a large city in Kentucky, USA called Lexington. However, this city is in the heart of Appalachia. The Appalachians are well known for their unhealthy lifestyle that may consider as a way of coping with the stressors. We recommend to include the cultural factor in the future studies. A final possible explanation is that there is no relationship between the variables and outcomes in patients with HF.

The strengths of our study include the use of valid and reliable instruments to measure stress, cognitive appraisal, coping, and other covariates. Furthermore, we investigated multiple associations among the variables of this study and our findings form a foundation for future studies of stress, cognitive appraisal, coping, and health outcomes in HF patients. The small sample size is one of the limitations of this study that may affect our ability to find significant association similar to those that were presented in the literature. We also did not adjust the analysis for the length of time from diagnosis which may have affected the perception of HF in this population. Including this variable in the analysis could have provided more insights into our finding. Furthermore, choosing the unhealthy style of coping to manage the stressors associated with HF, it can be a chance to develop anxiety and depression among those patients which may affect their survival. Thus, not including anxiety and depression as variables may consider a limitation in this study.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that there is an association between stress level and harm/loss cognitive appraisal that is associated with shorter event free survival among HF patients. In addition, harm /loss cognitive appraisal is associated with avoidant emotional coping that is associated with negative health outcomes and shorter event-free survival. Thus, to improve health outcomes in patients with HF, interventions are needed to reduce the stress from HF and change how HF patients appraise their condition and cope with it. Cognitive restructuring may be useful among patients with HF who negatively appraise the stress of HF as such appraisal leads to negative coping strategies that are associated with worse event-free survival.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research [NIH, NINR P20 Center funding 5P20NR010679; NIH, NINR 1 R01 NR009280 (Terry Lennie PI) and R01 NR008567 (Debra Moser, PI)], and K23 NR013480 (Rebecca Dekker).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health. Financial sponsors played no role in the design, execution, analysis, and interpretation of data or writing of the study.

Abbreviations

- HF

Heart failure

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All of the Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gheorghiade M, Vaduganathan M, Fonarow GC, Bonow RO. Rehospitalization for heart failure: problems and perspectives. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013 Jan 29;61(4):391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidney S, Rosamond WD, Howard VJ, Luepker RV, National Forum for Heart D, Stroke P The “heart disease and stroke statistics–2013 update” and the need for a national cardiovascular surveillance system. Circulation. 2013 Jan 1;127(1):21–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.155911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation Heart failure. 2013 May;6(3):606–619. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999 Apr 27;99(16):2192–2217. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.16.2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett SJ, Pressler ML, Hays L, Firestine LA, Huster GA. Psychosocial variables and hospitalization in persons with chronic heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs Fall. 1997;12(4):4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kupper N, Pelle AJ, Szabo BM, Denollet J. The relationship between Type D personality, affective symptoms and hemoglobin levels in chronic heart failure. PloS one. 2013;8(3):e58370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cene CW, Loehr L, Lin FC, et al. Social isolation, vital exhaustion, and incident heart failure: findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. European journal of heart failure. 2012 Jul;14(7):748–753. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallacher K, May CR, Montori VM, Mair FS. Understanding patients’ experiences of treatment burden in chronic heart failure using normalization process theory. Annals of family medicine. 2011 May-Jun;9(3):235–243. doi: 10.1370/afm.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konstam V, Moser DK, De Jong MJ. Depression and anxiety in heart failure. Journal of cardiac failure. 2005 Aug;11(6):455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moser DK, Dracup K, Evangelista LS, et al. Comparison of prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, and hostility in elderly patients with heart failure, myocardial infarction, and a coronary artery bypass graft. Heart Lung. 2010 Sep-Oct;39(5):378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esch T. Health in stress: change in the stress concept and its significance for prevention, health and life style. Gesundheitswesen. 2002 Feb;64(2):73–81. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selye H. The evolution of the stress concept. Am Sci. 1973 Nov-Dec;61(6):692–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rozanski A, Krantz DS, Bairey CN. Ventricular responses to mental stress testing in patients with coronary artery disease. Pathophysiological implications. Circulation. 1991 Apr;83(4 Suppl):II137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor KAA, Maurizio A. The prospect of negotiating: Stress, cognitive appraisal, and performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46(5):729–735. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey A, Nathens AB, Bandiera G, Leblanc VR. Threat and challenge: cognitive appraisal and stress responses in simulated trauma resuscitations. Med Educ. 2010 Jun;44(6):587–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maier KJ, Waldstein SR, Synowski SJ. Relation of cognitive appraisal to cardiovascular reactivity, affect, and task engagement. Annals of behavioral medicine: a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2003 Aug;26(1):32–41. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodes M, Jagdev D, Chandra N, Cunniff A. Risk and resilience for psychological distress amongst unaccompanied asylum seeking adolescents. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2008 Jul;49(7):723–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnider KR, Elhai JD, Gray MJ. Coping style use predicts posttraumatic stress and complicated grief symptom severity among college students reporting a traumatic loss. J Couns Psychol. 2007 Jul;54(3):344–350. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnider K, Elhai J, Gray M. Coping Style Use Predicts Posttraumatic Stress and Complicated Grief Symptom Severity Among College Students Reporting a Traumatic Loss. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54(3):344–350. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989 Feb;56(2):267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J Health Soc Behav. 1980 Sep;21(3):219–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Spring Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Halpert JA. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychol Bull. 2003 May;129(3):447–466. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler TA. The Cognitive Appraisal of Health Scale: development of psychometric evaluation. Res Nurs Health. 1998 Feb;21(1):73–82. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199802)21:1<73::aid-nur8>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Well S, Kolk AM, Klugkist IG. Effects of sex, gender role identification, and gender relevance of two types of stressors on cardiovascular and subjective responses: sex and gender match and mismatch effects. Behavior modification. 2008 Jul;32(4):427–449. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004 May;130(3):355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roesch SC, Adams L, Hines A, et al. Coping with prostate cancer: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med. 2005 Jun;28(3):281–293. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-4664-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folkman S. Personal control and stress and coping processes: a theoretical analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984 Apr;46(4):839–852. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galvin LR, Godfrey HP. The impact of coping on emotional adjustment to spinal cord injury (SCI): review of the literature and application of a stress appraisal and coping formulation. Spinal Cord. 2001 Dec;39(12):615–627. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berenbaum JPBaH. Emotional approach and problem-focused coping: A comparison of potentially adaptive strategies. COGNITION AND EMOTION. 2007;21(1):95–118. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herman JLT, Lois E. Problem-focused versus emotion-focused coping strategies and repatriation adjustment. Human Resource Management. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983 Dec;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee EH, Chung BY, Suh CH, Jung JY. Korean versions of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14, 10 and 4): psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic disease. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015 Mar;29(1):183–192. doi: 10.1111/scs.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ezzati A, Jiang J, Katz MJ, Sliwinski MJ, Zimmerman ME, Lipton RB. Validation of the Perceived Stress Scale in a community sample of older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014 Jun;29(6):645–652. doi: 10.1002/gps.4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmad MM. Psychometric evaluation of the Cognitive Appraisal of Health Scale with patients with prostate cancer. Journal of advanced nursing. 2005 Jan;49(1):78–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmad MM. Validation of the Cognitive Appraisal Health Scale with Jordanian patients. Nursing & health sciences. 2010 Mar;12(1):74–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. International journal of behavioral medicine. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nahlen Bose C, Persson H, Bjorling G, Ljunggren G, Elfstrom ML, Saboonchi F. Evaluation of a Coping Effectiveness Training intervention in patients with chronic heart failure - a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016 Jan 5; doi: 10.1177/1474515115625033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carver CS, Scheier MF. Situational coping and coping dispositions in a stressful transaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994 Jan;66(1):184–195. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu JR, Moser DK, Chung ML, Lennie TA. Objectively measured, but not self-reported, medication adherence independently predicts event-free survival in patients with heart failure. Journal of cardiac failure. 2008 Apr;14(3):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song EK, Moser DK, Frazier SK, Heo S, Chung ML, Lennie TA. Depressive symptoms affect the relationship of N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide to cardiac event-free survival in patients with heart failure. Journal of cardiac failure. 2010 Jul;16(7):572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014 Jan 21;129(3):399–410. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000442015.53336.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stehlik J, Feldman DS. Arrhythmias in heart failure: beyond sudden cardiac death. Current opinion in cardiology. 2013 May;28(3):315–316. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328360445e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adams KF, Jr, Zannad F. Clinical definition and epidemiology of advanced heart failure. Am Heart J. 1998 Jun;135(6 Pt 2 Su):S204–215. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacMahon KM, Lip GY. Psychological factors in heart failure: a review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Mar 11;162(5):509–516. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alhurani AS, Dekker R, Tovar E, et al. Examination of the potential association of stress with morbidity and mortality outcomes in patient with heart failure. SAGE open medicine. 2014 Dec;:2. doi: 10.1177/2050312114552093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alhurani AS, Dekker RL, Abed MA, et al. The association of co-morbid symptoms of depression and anxiety with all-cause mortality and cardiac rehospitalization in patients with heart failure. Psychosomatics. 2015 Jul-Aug;56(4):371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nash VR, Ponto J, Townsend C, Nelson P, Bretz MN. Cognitive behavioral therapy, self-efficacy, and depression in persons with chronic pain. Pain management nursing : official journal of the American Society of Pain Management Nurses. 2013 Dec;14(4):e236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses. Cognitive therapy and research. 2012 Oct 1;36(5):427–440. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meade CS, Wang J, Lin X, Wu H, Poppen PJ. Stress and coping in HIV-positive former plasma/blood donors in China: a test of cognitive appraisal theory. AIDS and behavior. 2010 Apr;14(2):328–338. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9494-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aarstad AK, Aarstad HJ, Bru E, Olofsson J. Psychological coping style versus disease extent, tumour treatment and quality of life in successfully treated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Clinical otolaryngology : official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2005 Dec;30(6):530–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2005.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eisenberg SA, Shen BJ, Schwarz ER, Mallon S. Avoidant coping moderates the association between anxiety and patient-rated physical functioning in heart failure patients. J Behav Med. 2012 Jun;35(3):253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9358-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Graven LJ, Grant JS. Coping and health-related quality of life in individuals with heart failure: An integrative review. Heart & Lung. 2013 May-Jun;42(3):183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carels RA. The association between disease severity, functional status, depression and daily quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2004 Feb;13(1):63–72. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000015301.58054.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vollman MW, Lamontagne LL, Hepworth JT. Coping and depressive symptoms in adults living with heart failure. The Journal of cardiovascular nursing. 2007 Mar-Apr;22(2):125–130. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200703000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yakhnich L, Ben-Zur H. Personal resources, appraisal, and coping in the adaptation process of immigrants from the Former Soviet Union. The American journal of orthopsychiatry. 2008 Apr;78(2):152–162. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramirez-Maestre C, Esteve R, Lopez AE. Cognitive appraisal and coping in chronic pain patients. European journal of pain. 2008 Aug;12(6):749–756. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hamama-Raz Y, Solomon Z, Schachter J, Azizi E. Objective and subjective stressors and the psychological adjustment of melanoma survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2007 Apr;16(4):287–294. doi: 10.1002/pon.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andreou E, Alexopoulos EC, Lionis C, et al. Perceived Stress Scale: reliability and validity study in Greece. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2011 Aug;8(8):3287–3298. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8083287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leung DY, Lam TH, Chan SS. Three versions of Perceived Stress Scale: validation in a sample of Chinese cardiac patients who smoke. BMC public health. 2010;10:513. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]