Abstract

Objective

Measuring motor function in mice is important for studying models of spinal cord injury (SCI) or other diseases. Several methods exist based on visual observation of mice moving in an open field. Though these methods require very little equipment, observers must be trained, and the possibility of human error or subjectivity cannot be eliminated. The Noldus CatWalk XT Automated Gait Analysis system assesses mouse motor function by taking high-resolution videos of the mice, with specialized software to measure several aspects of the animal’s gait. This instrument reduces the possibility of human error, but it is not always clear what data is important for assessing motor function. This study used data collected during mouse SCI experiments to create a simple mathematical model that combines the data collected by the CatWalk system into a single score, the Combined CatWalk Index or CCI.

Results

The CCI system produces similar results to the Basso Mouse Scale or the CatWalk’s Step Sequence Regularity Index. However, the CCI has a significantly smaller coefficient of variation than either other method. Additionally, CCI scoring shows slightly better correlation with impact force. The CCI system is likely to be a useful tool for SCI research.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13104-018-3374-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Locomotor function, Mouse, New scoring, CatWalk, Combined Catwalk Index

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) research often relies on animal models. Several methods exist to create animal models of SCI and to assess motor function recovery after injury. Open-field locomotion methods are particularly popular because they require very little equipment. Any flat surface large enough for the animal to freely walk on is usually acceptable. The Basso-Beattie-Bresnahan (BBB) Scale [1] was developed to measure motor function in rats. The Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) [2] was developed later to accommodate for the differences in motor function recovery between mice and rats. The BMS system has been further modified and extended to create other measurement scales, such as the Toyama Mouse Scale (TMS) [3], which is designed to emphasize weight support and reduce the ambiguity seen in the BMS, which can assign the same score to mice with different combinations of stepping frequency, coordination, etc. When properly performed, these methods are reliable and repeatable. However, all of these methods require trained observers. To increase reliability, mice should be observed by at least 2 different observers, and the observers must be blinded to the experiment. Not all laboratories are able to meet these requirements, and the possibility of human error or subjective measurement cannot be ruled out.

More objective methods to assess mouse motor function usually require some form of instrument or other equipment. The Noldus CatWalk XT Automated Gait Analysis System [4, 5] uses an instrument with a glass platform above a high-resolution video camera. Green light is internally reflected through the glass platform. As the mouse walks along the platform, light is reflected down towards the camera wherever the mouse contacts the glass. The intensity of the reflected light is proportional to the pressure placed on the glass. Proprietary software analyzes the videos and produces a large amount of data to describe several aspects of how the animal walks, including speed, timing, coordination, etc. The software produces approximately 25 different measurements for each paw, plus measurements for the mouse overall, for a total of approximately 104 parameters. The large amount of data produced by the CatWalk software is too much to reasonably present everything in a single publication, so a subset of parameters must be chosen. This choice can be arbitrary, and it is difficult to know if the chosen parameters are relevant or adequate for a given experiment. Researchers may be tempted to present any parameter that shows a desired statistically significant result, even if that parameter is not actually relevant to the study.

This study was carried out to produce a method that combines all CatWalk parameters into a single score, the Combined CatWalk Index (CCI), so that the results are easier to compare and report. The data used in this study was collected during a series of experiments utilizing a mouse model of SCI.

Main text

Several SCI experiments were performed using female C57BL/6J mice (Charles River Japan, Yokohama, Japan), including experiments to test potential therapeutics as well as impact force optimization experiments. The data used in this study was collected from approximately 800 measurements taken from 108 mice.

Mice were anesthetized using an intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of 0.3 mg/kg Medetomidine, 4 mg/kg Midazolam, and 5 mg/kg Butorphanol. Anesthesia was confirmed by pinching the hind paw prior to surgery. The spinal cord was exposed by laminectomy at the 11th thoracic vertebra. Contusion SCI was performed using the Infinite Horizons IH-0400 Impactor [6] (Precision Systems and Instrumentation LLC, Fairfax, VA, USA) using peak impact forces between 40 and 70 kdyne. The animal’s bladders were manually pressed every day to drain the urine and prevent urinary tract infections. After all motor function measurements were completed, mice were anesthetized again and euthanized by cervical dislocation.

Motor function was monitored using the Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) and Noldus CatWalk XT (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands) every week for 6 weeks post-injury.

BMS data was collected by observing a mouse in a 30 × 30 × 15 cm plastic cage for 5 min. Notes were taken describing several aspects of the animal’s gait, and BMS scores were calculated according to a flowchart [2].

CatWalk data was collected using a gain of 0.18, with a maximum compliant run time of 12.5 s. When possible, three compliant runs were recorded for each mouse, but poorly performing mice were often unable to produce runs faster than 12.5 s. In these cases, three non-compliant runs were collected. Runs were rejected if the animal turned around during the run. Post-injury data from each mouse was compared to a pre-injury baseline made of three pre-injury measurements to account for naturally occurring variation in motor function.

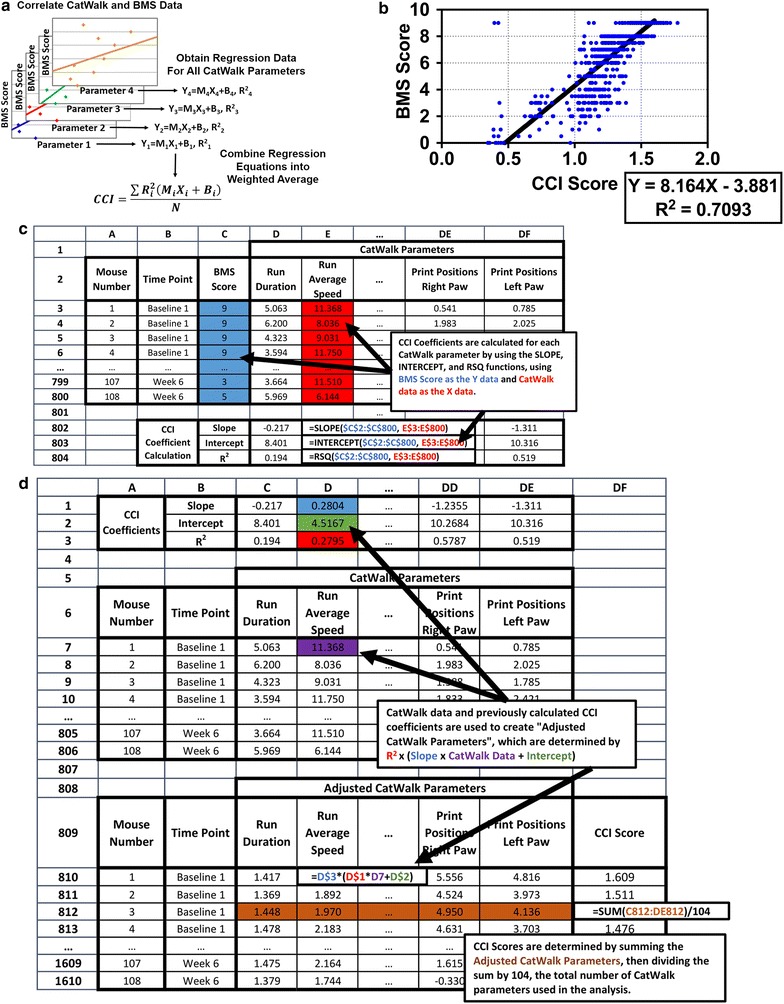

The Combined CatWalk Index (CCI) was developed by correlating 104 CatWalk parameters against observed BMS scores using linear regression, then combining all linear regression equations into a single weighted average (Fig. 1a). The R2 values are used as the weighting values, so that parameters with strong correlation have strong weights, while poorly correlating parameters have weak weights. Calculations were performed using both Microsoft Excel 2013 and LibreOffice Calc version 5, both programs produced identical results. Linear regression was performed on each parameter using the built-in SLOPE, INTERCEPT, and RSQ functions, which calculate the slope, Y intercept, and R2 values for a linear regression equation (Fig. 1c). Using these formulas is much simpler than preparing a separate scatterplot for each parameter and linear regression. BMS scores were used as the Y-axis data and CatWalk parameters were used as the X-axis data. The CCI coefficients (slope, intercept, and R2 values) for each parameter are listed in Table 1, in order from highest to lowest R2.

Fig. 1.

a Schematic of how CCI scores are calculated. Data from N CatWalk parameters is correlated with BMS data using linear regression. Each parameter produces a slope (M), Y-Intercept (B), and R2, which are listed in Table 1. The CCI score is then determined using a weighted average of each CatWalk parameter using MX + B linear equations multiplied by R2 as the weighting factor. b Plot of CCI scores against corresponding BMS scores. CCI scores correlate with BMS scores with an R2 value of 0.7093, slightly higher than the CatWalk parameter with the highest R2 value (Step Sequence Regularity Index, R2 = 0.7048). c Example of how the CCI coefficients are determined from BMS to CatWalk data using a spreadsheet. Linear regressions are performed for each CatWalk Parameter using the SLOPE, INTERCEPT, and RSQ functions. d Example of how CCI scores are calculated from CCI coefficients and CatWalk data. Each CatWalk parameter is multiplied by its CCI coefficients to create an “Adjusted CatWalk Parameter”. The adjusted CatWalk parameters are summed and divided by 104, the number of CatWalk parameters used to create the CCI coefficients

Table 1.

List of CatWalk parameters and their slope, intercept, and R2 coefficients determined by linear regression against BMS data

| Rank | CatWalk parameter name | Slope | Intercept | R2 | Rank | CatWalk parameter name | Slope | Intercept | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | StepSequence_RegularityIndex_(%) | 0.070 | 2.486 | 0.705 | 53 | RF_PrintArea_(cm2)_Mean | − 17.88 | 8.937 | 0.119 |

| 2 | PrintPositions_RightPaws_Mean_(cm) | − 1.235 | 10.268 | 0.579 | 54 | RH_StepCycle_(s)_Mean | − 1.213 | 7.970 | 0.118 |

| 3 | LH_MaxContactMeanIntensity_Mean | 0.222 | − 11.437 | 0.519 | 55 | RF_MaxContactArea_(cm2)_Mean | − 21.83 | 8.790 | 0.113 |

| 4 | PrintPositions_LeftPaws_Mean_(cm) | − 1.311 | 10.316 | 0.519 | 56 | RH_PrintArea_(cm2)_Mean | 11.857 | 6.034 | 0.109 |

| 5 | LH_MeanIntensity_Mean | 0.213 | − 11.455 | 0.512 | 57 | RH_Swing_(s)_Mean | − 1.300 | 7.532 | 0.108 |

| 6 | RF_DutyCycle_(%)_Mean | − 0.154 | 17.709 | 0.497 | 58 | LH_MaxIntensityAt_(%)_Mean | 0.071 | 4.116 | 0.103 |

| 7 | RH_MaxContactMeanIntensity_Mean | 0.203 | − 9.815 | 0.486 | 59 | LH_StandIndex_Mean | − 0.227 | 5.899 | 0.102 |

| 8 | RH_MeanIntensity_Mean | 0.202 | − 10.367 | 0.478 | 60 | RH_SingleStance_(s)_Mean | − 8.141 | 8.313 | 0.098 |

| 9 | RH_MaxIntensity_Mean | 0.057 | − 0.639 | 0.474 | 61 | LH_SingleStance_(s)_Mean | − 5.196 | 8.041 | 0.094 |

| 10 | RH_MaxContactMaxIntensity_Mean | 0.059 | − 0.496 | 0.471 | 62 | RF_MinIntensity_Mean | 0.622 | − 27.47 | 0.093 |

| 11 | LH_MaxIntensity_Mean | 0.059 | − 0.802 | 0.468 | 63 | RH_StandIndex_Mean | − 0.202 | 6.057 | 0.088 |

| 12 | LH_MaxContactMaxIntensity_Mean | 0.061 | -0.720 | 0.467 | 64 | LF_StepCycle_(s)_Mean | − 4.048 | 8.932 | 0.088 |

| 13 | LH_SwingSpeed_(cm/s)_Mean | 0.096 | 3.890 | 0.467 | 65 | RH_MaxIntensityAt_(%)_Mean | 0.065 | 4.427 | 0.088 |

| 14 | LH_MeanIntensityOfThe15MostIntensePixels_Mean | 0.072 | − 0.771 | 0.465 | 66 | RF_SwingSpeed_(cm/s)_Mean | − 0.065 | 9.401 | 0.087 |

| 15 | RH_MeanIntensityOfThe15MostIntensePixels_Mean | 0.069 | − 0.416 | 0.441 | 67 | RF_StepCycle_(s)_Mean | − 4.139 | 8.980 | 0.085 |

| 16 | LF_DutyCycle_(%)_Mean | − 0.153 | 17.519 | 0.437 | 68 | RF_PrintWidth_(cm)_Mean | − 3.121 | 9.417 | 0.084 |

| 17 | LF_SingleStance_(s)_Mean | 36.619 | 2.973 | 0.429 | 69 | LH_StrideLength_(cm)_Mean | 0.406 | 5.620 | 0.070 |

| 18 | RH_SwingSpeed_(cm/s)_Mean | 0.085 | 4.312 | 0.417 | 70 | LF_MaxContactArea_(cm2)_Mean | − 17.90 | 8.405 | 0.069 |

| 19 | RF_StrideLength_(cm)_Mean | 1.214 | 2.546 | 0.393 | 71 | LF_StandIndex_Mean | − 0.431 | 5.330 | 0.069 |

| 20 | LF_StrideLength_(cm)_Mean | 1.189 | 2.638 | 0.371 | 72 | LF_PrintWidth_(cm)_Mean | − 2.836 | 9.171 | 0.068 |

| 21 | RF_Swing_(s)_Mean | 28.297 | 3.691 | 0.368 | 73 | LF_PrintArea_(cm2)_Mean | − 13.93 | 8.456 | 0.065 |

| 22 | LF_Swing_(s)_Mean | 33.472 | 3.063 | 0.365 | 74 | RF_BodySpeedVariation_(%)_Mean | − 0.021 | 8.099 | 0.062 |

| 23 | RF_SingleStance_(s)_Mean | 36.982 | 2.867 | 0.363 | 75 | LF_BodySpeedVariation_(%)_Mean | − 0.017 | 7.912 | 0.049 |

| 24 | LH_PrintLength_(cm)_Mean | 7.436 | 3.049 | 0.342 | 76 | RF_MaxContactAt_(%)_Mean | − 0.070 | 10.161 | 0.038 |

| 25 | LH_BodySpeed_(cm/s)_Mean | 0.270 | 4.546 | 0.341 | 77 | RF_PrintLength_(cm)_Mean | − 4.888 | 10.046 | 0.038 |

| 26 | RH_DutyCycle_(%)_Mean | 0.092 | 1.449 | 0.337 | 78 | BOS_HindPaws_Mean_(cm) | 0.504 | 5.866 | 0.038 |

| 27 | LH_DutyCycle_(%)_Mean | 0.099 | 0.907 | 0.334 | 79 | RF_MeanIntensityOfThe15MostIntensePixels_Mean | − 0.033 | 10.442 | 0.034 |

| 28 | LH_MaxContactArea_(cm2)_Mean | 34.560 | 4.844 | 0.325 | 80 | RF_MaxContactMeanIntensity_Mean | − 0.120 | 16.638 | 0.033 |

| 29 | RH_BodySpeed_(cm/s)_Mean | 0.256 | 4.659 | 0.304 | 81 | RH_StrideLength_(cm)_Mean | 0.258 | 6.195 | 0.033 |

| 30 | Run_Average_Speed_(cm/s)_Mean | 0.280 | 4.517 | 0.279 | 82 | RF_MaxIntensityAt_(%)_Mean | − 0.060 | 10.589 | 0.033 |

| 31 | LH_Swing_(s)_Mean | − 4.903 | 8.134 | 0.277 | 83 | RF_MeanIntensity_Mean | − 0.093 | 14.731 | 0.025 |

| 32 | RH_MaxContactArea_(cm2)_Mean | 30.206 | 5.159 | 0.268 | 84 | LF_SwingSpeed_(cm/s)_Mean | − 0.035 | 8.215 | 0.024 |

| 33 | RF_BodySpeed_(cm/s)_Mean | 0.265 | 4.422 | 0.253 | 85 | RF_MaxContactMaxIntensity_Mean | − 0.025 | 10.206 | 0.023 |

| 34 | LF_BodySpeed_(cm/s)_Mean | 0.261 | 4.475 | 0.250 | 86 | LH_Stand_(s)_Mean | − 1.254 | 7.615 | 0.021 |

| 35 | RH_MinIntensity_Mean | − 0.486 | 34.320 | 0.244 | 87 | RF_MaxIntensity_Mean | − 0.021 | 9.839 | 0.020 |

| 36 | RF_InitialDualStance_(s)_Mean | − 9.510 | 8.244 | 0.236 | 88 | LH_BodySpeedVariation_(%)_Mean | − 0.012 | 7.769 | 0.017 |

| 37 | LF_TerminalDualStance_(s)_Mean | − 8.467 | 8.145 | 0.224 | 89 | RH_BodySpeedVariation_(%)_Mean | -0.004 | 7.379 | 0.016 |

| 38 | RF_TerminalDualStance_(s)_Mean | − 10.22 | 8.314 | 0.219 | 90 | RH_Stand_(s)_Mean | − 1.159 | 7.598 | 0.016 |

| 39 | LH_PrintArea_(cm2)_Mean | 19.742 | 5.300 | 0.218 | 91 | LF_MaxContactMeanIntensity_Mean | − 0.070 | 12.532 | 0.012 |

| 40 | RH_MaxContactAt_(%)_Mean | 0.087 | 3.924 | 0.212 | 92 | LF_MinIntensity_Mean | 0.208 | − 4.589 | 0.010 |

| 41 | LF_InitialDualStance_(s)_Mean | − 10.51 | 8.312 | 0.211 | 93 | LF_MeanIntensityOfThe15MostIntensePixels_Mean | − 0.016 | 8.610 | 0.008 |

| 42 | LH_MinIntensity_Mean | − 0.499 | 35.113 | 0.207 | 94 | LF_MeanIntensity_Mean | − 0.049 | 11.034 | 0.007 |

| 43 | LH_MaxContactAt_(%)_Mean | 0.087 | 3.900 | 0.203 | 95 | LH_InitialDualStance_(s)_Mean | − 0.712 | 7.456 | 0.004 |

| 44 | RF_Stand_(s)_Mean | − 5.729 | 9.090 | 0.201 | 96 | LF_MaxContactAt_(%)_Mean | − 0.023 | 7.986 | 0.004 |

| 45 | Run_Duration_(s)_Mean | − 0.217 | 8.401 | 0.194 | 97 | LF_MaxContactMaxIntensity_Mean | − 0.010 | 8.206 | 0.004 |

| 46 | LF_Stand_(s)_Mean | − 5.481 | 9.001 | 0.190 | 98 | Run_Maximum_Variation_(%)_Mean | − 0.006 | 7.344 | 0.004 |

| 47 | LH_StepCycle_(s)_Mean | − 2.866 | 8.798 | 0.187 | 99 | RH_TerminalDualStance_(s)_Mean | − 0.840 | 7.429 | 0.003 |

| 48 | RH_PrintLength_(cm)_Mean | 4.539 | 4.648 | 0.186 | 100 | LF_MaxIntensity_Mean | − 0.007 | 7.897 | 0.002 |

| 49 | BOS_FrontPaws_Mean_(cm) | − 1.572 | 9.967 | 0.148 | 101 | LH_TerminalDualStance_(s)_Mean | − 0.357 | 7.411 | 0.000 |

| 50 | LH_PrintWidth_(cm)_Mean | 3.110 | 5.220 | 0.143 | 102 | LF_PrintLength_(cm)_Mean | − 0.389 | 7.209 | 0.000 |

| 51 | RF_StandIndex_Mean | − 0.582 | 4.712 | 0.139 | 103 | LF_MaxIntensityAt_(%)_Mean | − 0.002 | 7.101 | 0.000 |

| 52 | RH_PrintWidth_(cm)_Mean | 2.858 | 5.406 | 0.130 | 104 | RH_InitialDualStance_(s)_Mean | 0.017 | 7.316 | 0.000 |

Parameters are sorted by R2 value to place parameters with better correlation at the top

The CCI Score was calculated by combining all equations into a weighted average. “Adjusted CatWalk Parameters” were calculated using the original CatWalk data and CCI coefficients with this equation: R2 (Slope × CatWalk Parameter + Intercept) (Fig. 1d). Adjusted CatWalk Parameters were then summed and the sum was divided by 104, the number of CatWalk parameters used in this analysis. Mock ups of the spreadsheets used to calculate the CCI coefficients and CCI scores are shown in Fig. 1c, d, and an example spreadsheet containing the BMS and CatWalk data from impact force optimization experiments is available in Additional file 1.

CCI scores were calculated for every mouse at every time point based on the CatWalk data and the CCI coefficients in Table 1. The CCI scores were plotted against the corresponding BMS measurements and linear regression was used to determine how well the two scores correlated against each other, and an R2 value of 0.7093 was obtained (Fig. 1b). This R2 value is not perfect, but may be a reflection of the BMS system only being semi-quantitative. For example, if a mouse’s BMS score changes from 1 to 2 (a change from only showing partial ankle movement to full ankle movement without plantar placement), it is not the same as a change from 2 to 3 (the mouse shows plantar paw placement without weight support).

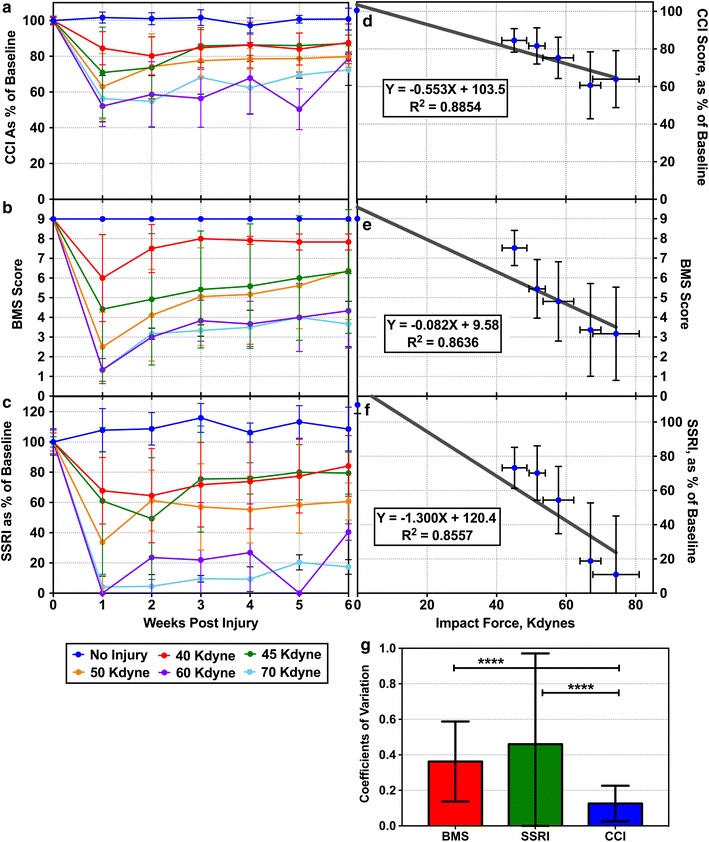

Table 1 shows that the CatWalk parameter that most closely correlates with BMS scores is the Step Sequence Regularity Index (SSRI), with an R2 of 0.7048, slightly lower than the R2 value for the correlation between BMS score and CCI score, but this difference is likely insignificant. The SSRI measures coordination by determining if the order of footprints falls into one of six regular patterns. Mice with poor motor function have poor coordination, and do not follow these regular patterns well, producing low SSRI scores. SSRI is often reported in studies that use the CatWalk system [4, 7–11], and the high correlation with BMS scores supports this practice. SSRI was chosen to represent CatWalk data when comparing CCI to CatWalk data in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

a–c Comparison of CCI to BMS and SSRI. Mice were given SCI at different impact forces and monitored by BMS and CatWalk methods for 6 weeks post-injury. CCI scores were calculated and plotted in (a), while BMS scores are plotted in (b). Step Sequence Regularity Index (SSRI) is plotted in (c) to represent the CatWalk parameter that mostly closely correlated with BMS score. All three scoring methods show similar patterns of motor function recovery. d–f Average CCI, BMS, and SSRI scores at each injury level were plotted against impact. CCI produces a slightly better correlation (R2 = 0.8854) than BMS (R2 = 0.8636) or SSRI (R2 = 0.8557). g Coefficients of variation (CV) at each time point in plots (a–c) were determined and averaged. The CCI method has a significantly smaller CV than BMS or SSRI (P < 0.0001 for each, determined by unpaired 2-tailed T Test). All error bars represent sample standard deviation

Data from the impact force optimization experiments was used to compare CCI scores to BMS scores and SSRI scores. Mean scores and sample standard deviations for each impact force were plotted for every time point (Fig. 2a–c). CCI and SSRI scores are presented as a percent of pre-injury baseline to account for naturally occurring variation between mice. BMS scores are presented directly, because all non-injured mice have a BMS score of 9, so there is no pre-injury variation. All three methods showed similar trends, with higher impact forces producing lower scores. All three methods show fairly large standard deviations, demonstrating the difficulty in producing consistent levels of injury with the contusion SCI model. This is in part due to the difficulty of controlling the Infinite Horizons impactor’s peak impact force. Actual impact forces were usually higher than the desired impact force, with substantial variation.

Average scores for each impact force were estimated by calculating the mean score across weeks 1–6 and were plotted against impact force (Fig. 2d–f). Linear regression was used to determine how well each method correlated with impact force. The CCI scores had a slightly higher R2 value (0.8854) than BMS (0.8636) or SSRI (0.8557). This indicates that the CCI score correlates well with the peak impact force in this contusion SCI model.

Coefficients of variation (CV) at each impact force and time point were determined by dividing the sample standard deviation by the mean. Each method’s CVs were averaged and compared using an unpaired, two-tailed T Test (Fig. 2g). The CCI method showed significantly smaller CV than either the BMS method or the SSRI method (P < 0.0001). This implies that the CCI method may be more precise than either other method.

One advantage of the human-observation based BMS method is that it produces a single score that can be easily be compared between mice, but suffers from the potential for human error and the requirement for training. The CatWalk system has the advantage of greater objectivity, but the large number of measurements can complicate several things, such as choosing parameters for publication or making comparisons between mice. For example, if one of set of mice has better coordination, but another set of mice has higher speed, which set of mice has better overall motor function? The Combined CatWalk Index appears to combine the advantages of both system by creating a single number based on objectively determined data. In addition, the CCI scores have slightly better correlation with BMS scores than any individual CatWalk parameter (Fig. 1b, Table 1), slightly better correlation with impact force than BMS scores or SSRI scores (Fig. 2d–f), and significantly smaller coefficients of variation than BMS scores or SSRI scores (Fig. 2g).

Although the CCI method requires a specialized instrument, the CatWalk system is fairly simple, and users can be quickly trained to measure mice. The BBB, BMS, and TMS systems require more extensive training, and steps must be taken to remove human bias or interrater variability. Additionally, the CCI method could potentially be modified and applied to any disease model that can be studied using the CatWalk system, such as chronic pain [12], arthritis, or vestibular disease [11]. The main requirement is to have some semi-quantitative method to rank mice so that correlation between rank and CatWalk parameters can be determined.

Limitations

The CCI was created by using linear regression of 104 CatWalk parameters against observed BMS scores. The BMS scores were collected by an untrained observer, so the quality of the BMS data might not be optimal, but the decent correlation between BMS score and impact force in Fig. 2e suggests that they are probably sufficient for this analysis. A more significant limitation may be the linear regression model. More sophisticated multivariate regression models exist, but can be more difficult to use with large data sets. For example, the multiple regression method built into Microsoft Excel 2013 can only accept up to 16 variables. The method presented here is a simple extension of linear regression that can be understood and used by almost any researcher using common, or even open source, software.

Finally, good SCI scoring systems should also correlate with spinal cord damage. Systematic histological studies were not performed to verify a link between CCI score and tissue damage, but the close agreement between CCI and the more thoroughly studied BMS and CatWalk systems suggests that CCI is likely to predict spinal cord tissue damage.

Additional file

Additional file 1. Example spreadsheet with CCI coefficients. An annotated example spreadsheet containing CatWalk and BMS data from impact force optimization experiments. This spreadsheet shows how to calculate CCI coefficients and scores.

Authors’ contributions

STC: Study design, SCI surgeries, data collection and analysis, drafted the manuscript. KI and KK: Study design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Satoshi Uchida and Satomi Ogura for training STC to perform SCI surgical methods.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee at Innovation Center of NanoMedicine (iCONM), Kawasaki Institute of Industrial Promotion, 3-25-14 Tonomachi, Kawasaki-Ku, Kawasaki, 210-0821, Japan. The procedures were approved as Animal Experiment Plan A16-008-4 on May 23rd, 2017.

Funding

This work was financially supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP15H03017, 16K15642 (K.I.), JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship for Foreign Researchers (Grant Number 17F17410 (S.C. and K.I.), and Center of Innovation Program (COI) from MEXT.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- BBB

Basso-Beattie-Bresnahan Rat Scale

- BMS

Basso Mouse Scale

- CCI

Combined CatWalk Index

- CV

coefficient of variation

- SCI

spinal cord injury

- SSRI

Step Sequence Regularity Index

- TMS

Toyama Mouse Scale

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13104-018-3374-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Samuel T. Crowley, Email: samuel-c@kawasaki-net.ne.jp

Kazunori Kataoka, Email: kataoka@pari.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Keiji Itaka, Email: itaka.bif@tmd.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. A Sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12:1–21. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basso DM, Fisher LC, Anderson AJ, Jakeman LB, Mctigue DM, Popovich PG. Basso Mouse Scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:635–659. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shigyo M, Tanabe N, Kuboyama T, Choi S-H, Tohda C. New reliable scoring system, Toyama mouse score, to evaluate locomotor function following spinal cord injury in mice. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:332. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamers FPT, Lankhorst AJ, van Laar TJ, Veldhuis WB, Gispen WH. Automated quantitative gait analysis during overground locomotion in the rat: its application to spinal cord contusion and transection injuries. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18:187–201. doi: 10.1089/08977150150502613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamers FPT, Koopmans GC, Joosten EAJ. CatWalk-assisted gait analysis in the assessment of spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:537–548. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheff S, Roberts KN. Infinite horizon spinal cord contusion model. In: Chen J, Xu ZC, Xu XM, Zhang JH, editors. Animal models of acute neurological injuries. Totowa: Humana Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lankhorst AJ, ter Laak MP, van Laar TJ, van Meeteren NL, de Groot JC, Schrama LH, et al. Effects of enriched housing on functional recovery after spinal cord contusive injury in the adult rat. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18:203–215. doi: 10.1089/08977150150502622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koopmans GC, Deumens R, Honig WMM, Hamers FPT, Steinbusch HWM, Joosten EAJ. The assessment of locomotor function in spinal cord injured rats: the importance of objective analysis of coordination. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:214–225. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh A, Murray M, Houle JD. A training paradigm to enhance motor recovery in contused rats: effects of staircase training. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:24–34. doi: 10.1177/1545968310378510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y-J, Cheng F-C, Sheu M-L, Su H-L, Chen C-J, Sheehan J, et al. Detection of subtle neurological alterations by the Catwalk XT gait analysis system. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2014;11:62. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-11-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kopecky B, DeCook R, Fritzsch B. Mutational ataxia resulting from abnormal vestibular acquisition and processing is partially compensated for. Behav Neurosci. 2012;126:301–313. doi: 10.1037/a0026896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrinten DH, Hamers FFT. ‘Catwalk’ automated quantitative gait analysis as a novel method to assess mechanical allodynia in the rat; a comparison with von Frey testing. Pain. 2003;102:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00382-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Example spreadsheet with CCI coefficients. An annotated example spreadsheet containing CatWalk and BMS data from impact force optimization experiments. This spreadsheet shows how to calculate CCI coefficients and scores.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files.