Abstract

Through this study, we assessed the knowledge of EMS providers regarding needle stick injuries (NSIs) and examined differences by demographics. This cross-sectional study used a random sample of certified EMS providers in West Virginia. The survey consists of three sections: sociodemographic characteristics, whether or not got NSIs in the past 12 months, whether or not received needle stick training before. A total of 248 out of 522 (47.31%) EMS providers completed the survey. The majority of EMS providers (81.99%, n = 202) reported no NSI ever and 18.21% (n = 45) had at least one NSI within past 12 months. Chi square test was used and there was a statistically significant association between NSI occurrence and age (P < 0.01); certification level (P = 0.0005); and years of experience (P < 0.0001). Stratification methods were used and there was high varying proportion in NSIs between urban areas (38.50%) and rural areas (14.70%) among females (OR 0.28, CI 0.075–1.02, P = 0.05). Our survey of NSIs among EMS providers found that older, more highly certified, and more experienced providers reported higher frequencies of NSIs. Female EMS providers are more prone to NSIs in urban areas compared to women in rural areas. The results indicate a need to further examine NSIs and provide information regarding the safety precautions among urban and rural EMS providers.

Keywords: Emergency medical services, Injuries, Prehospital, Needlestick, Paramedic, EMS

Introduction

Occupational injury and illness occur across an extensive variety of occupations. An estimated 320,471 employees die annually from work-related transmittable infectious diseases worldwide [1]. Compared to many other types of occupations, health care workers (HCWs) are at a greater risk of harm from exposure to blood and other pathogens. A study reveals a high level of occupational exposure to blood among HCWs [2]. Emergency medical services (EMS) providers are often exposed to blood, resulting in concerns regarding transmission of blood-borne pathogens [3, 4]. This places EMS providers at higher risk of occupational exposure to infectious diseases.

Due to many needlestick injuries (NSIs) and the improper use of sharp devices, the needlestick safety and prevention act was created in 2000 to increase protections of HCWs from exposure to blood-borne pathogens [5]. However, NSIs are the most common occupational injuries among EMS providers worldwide [6, 7]. NSIs rate among EMS providers is higher than most hospital-based HCWs in United States [8, 9]. A study found that 80% of NSIs occurred without using proper safety devices [10]. Safety-engineered needles and sharps devices that are structurally developed are designed to reduce the risk of NSIs to HCWs including EMS providers [9]. Accordingly, training of how to use safety devices along with sufficient provision by the company contribute to decrease the rate of NSIs and other routes of blood exposure among EMS providers [10]. A study shows that there is a relative decease of NSIs among EMS providers due to the implantation of needlestick prevention polices, including self-capping needle devices and an annual review of all NSIs [4].

The risk of transmission of bloodborne pathogens can result in contracting infectious diseases. The most common bloodborne pathogens, which HCWs are often exposed to through percutaneous injuries including NSIs and sharps injuries or blood and body fluids exposure, are the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) [11]. Descriptive studies indicate an increase of acute HBV infection during 2006–2013 [12] and acute HCV infection from 2006 to 2012 among persons aged ≤ 30 years in rural areas [13]. These findings show that there was an increase in the level of NSIs among HCWs in rural areas, and therefore there is an urgent need for intervention [14].

EMS providers face increased levels of fatigue, reduced sleep, and encountered violence in rural areas [15, 16]. 55% of EMS providers in the United States suffer from fatigue, which is higher than approximately 40% of white-collar workers who also complain of fatigue [17]. Accordingly, poor sleep and fatigue adversely affect safety outcomes of EMS providers [18]. In addition, a pervious study shows that gender is associated with occupational exposure to blood, where male EMS providers are often more exposed to non-intact skin than female EMS providers [8]. Unfortunately, there is not enough information regarding percutaneous injuries, including NSIs and other sharp injuries among male and female EMS providers specifically in rural areas. The objective of this study was to assess the knowledge of EMS providers regarding NSIs and to examine differences by demographics.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This project was part of a cross-sectional survey conducted with a simple random sample of certified EMS providers in West Virginia regarding the knowledge, consistency, and practice of standard precaution among EMS providers. Given the anonymous nature of this project combined with the lack of protected health information this project was approved as exempt by the institutional review board. An invitation email was sent to randomly selected EMS agencies from a comprehensive list of providers from the Office of West Virginia Emergency Medical Services. 6 out of 12 different agencies replied and agreed to participate in distributing the survey link to their membership. The entire pool of certified EMS providers of these agencies totaled 522 EMS providers, varying from critical care paramedics, paramedics, EMT-advanced, EMT-basic, and emergency medical responders. Study instructions and an electronic cover letter were shown at the beginning of the survey. This study was approved by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board.

Survey Instrument

This project consists of three sections: socio-demographic characteristics, NSIs, and needle stick training.

The first section collected demographics, including age (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59 and 60+ years), gender (male and female), and place of residence, defined as urban or rural according to standards used by the US Census Bureau as reported by the United States Office of Management and Budget (OMB) [19]. Urban areas were defined as having a population of over 50,000. Rural areas were defined as having a population of less than 50,000. Additional demographics included level of certification (First responders, EMT-basic, EMT-intermediate, paramedics and critical care paramedics), employment status (full-time, part-time and volunteer) and years of service (< 5, 6–10, 11–15, and > 15 years).

The second section asked about whether or not EMS providers had needle stick prevention training before (yes/no).

The third section was focused on NSIs. EMS providers were asked about whether or not had gotten NSIs in the past 12 months (the year of 2016) (yes/no).

Survey Data Collection

The web based survey was administered using the secure, online software Qualtrics [20] via email from EMS agency directors in West Virginia. Certified EMS providers who were currently working in West Virginia and over 18 years old were included and eligible to complete the anonymous online survey. The web link to the online survey was active for 30 days from the time of sending out an email to EMS directors, and two reminder emails were sent. The EMS provider received the email and opened the hyperlink, which automatically took them to the website. At the beginning of the online survey, a general description of the study and the cover letter were provided to each respondent. After participants elected to take the survey, survey questions became available.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software, Version 9.4. Descriptive statistics were performed first to summarize EMS providers’ demographic characteristics, including summary tables, box-plots, frequencies, and proportions. Then, a Chi square test was used to compare categorical variables. All findings are reported using 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Furthermore, a logistic regression (adjusted model) was used to explain the relationship between independents and outcome. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. Differences at the α = 0.05 level were considered statistically significant.

Results

Description of the Study Participants

A total of 247 of 522 (47.31%) EMS providers completed the survey. 166 (67.21%) were male, and 81 (32.79%) were female. The majority of the EMS providers (194, 78.54%) reported working in a rural area, with 53 (21.46%) serving in urban areas. The majority of EMS providers were full-time (221, 89.47%); however, part-time and volunteer totaled 24 (9.72%) and 2 (0.81%), respectively. Most EMS providers were between the ages of 18 and 29 (84, 33.9%) and then between 30 and 39 (82, 33.20%), followed by 60 and above (6, 2.43%). A majority of EMS providers’ certifications were EMT-basic (107, 43.32%), followed by paramedics (80, 32.39%), while only 9 (3.64%) were first responders. 87 (35.22%) of EMS providers reported having less than 5 years of experience in EMS, followed by more than 15 years (70, 28.43%). EMS providers who had needlestick prevention training totaled 209 (84.62%), while 38 (15.38%) did not have any previous needlestick prevention training (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of EMS providers (n = 247)

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Needlestick injuries | |

| Yes | 45 (18.21) |

| No | 202 (81.78) |

| Residence | |

| Urban areas | 53 (21.46) |

| Rural areas | 194 (78.54) |

| Needlestick training | |

| Yes | 209 (84.62) |

| No | 38 (15.38) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 166 (67.21) |

| Female | 81 (32.79) |

| Age | |

| 18–29 | 83 (33.60) |

| 30–39 | 82 (33.20) |

| 40–49 | 51 (20.65) |

| 50–59 | 25 (10.12) |

| 60+ | 06 (2.43) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time | 221 (89.47) |

| Part-time | 24 (9.72) |

| Volunteer | 2 (0.81) |

| Levels of certification | |

| First responders (emergency medical) | 9 (3.64) |

| EMT-basics | 107 (43.32) |

| EMT-intermediate | 14 (5.67) |

| Paramedics | 80 (32.39) |

| Critical care paramedics | 37 (14.98) |

| Years of experience | |

| < 5 | 87 (35.22) |

| 6–10 | 56 (22.67) |

| 11–15 | 34 (13.77) |

| > 15 | 70 (28.34) |

EMT Emergency medical technician

Needlestick Injuries and EMS Providers

EMS providers reported of whether the EMS providers had NSIs past 12 months (the year of 2016). The majority of EMS providers (81.99%, n = 202) reported no NSI ever and 18.21% (n = 45) had at least one NSI within past 12 months (Table 1).

Chi square tests were used to evaluate the relationship between NSIs and demographics of the EMS providers (Table 2). There was a statistically significant association between age and NSIs (P = 0.001). EMS providers at age 60 years and older (50.00%) was the highest proportion among age group, followed by ages 50–59 (40.00%) and 40–49 (19.29%). Level of certification was statistically associated with NSIs (P = 0.0005). Critical care paramedics (32.43%) were the highest proportion of NSIs compared to paramedics (27.50%) and EMT-intermediate (21.43%), respectively. Also, years of experience was statistically associated with NSIs (P ≤ 0.0001). EMS providers with more than 15 years of experience (38.57%) were the highest proportion of participants who received NSIs, followed by those with 11–15 years of experience (14.71%). In contrast, gender, residence, needle stick training, and employment status were not significantly associated with NSIs.

Table 2.

Demographics of EMS providers reporting a NSI in Last 12 months (n = 247)

| Reported NSI (%) | n | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 30 (18.07) | 166 | |

| Female | 15 (18.52) | 81 | 0.93 |

| Residence | |||

| Urban areas | 14 (26.42) | 53 | |

| Rural areas | 31 (15.98) | 194 | 0.08 |

| Needlestick training | |||

| Yes | 41 (19.62) | 209 | |

| No | 4 (10.53) | 38 | 0.18 |

| Age | |||

| 18–29 | 7 (8.43) | 83 | |

| 30–39 | 15 (18.29) | 82 | |

| 40–49 | 10 (19.60) | 51 | |

| 50–59 | 10 (40.00) | 25 | |

| 60+ | 3 (50.00) | 6 | 0.001 |

| Employment status | |||

| Full-time | 43 (19.46) | 221 | |

| Part-time | 2 (8.33) | 24 | |

| Volunteer | 0 (0.00) | 2 | 0.32 |

| Levels of certification | |||

| First responders | 0 (0.00) | 9 | |

| EMT-basics | 8 (7.48) | 107 | |

| EMT-intermediate | 3 (21.43) | 14 | |

| Paramedics | 22 (27.50) | 80 | |

| Critical care paramedics | 12 (32.43) | 37 | 0.0005 |

| Years of experience | |||

| < 5 | 7 (8.05) | 87 | |

| 6–10 | 6 (10.71) | 56 | |

| 11–15 | 5 (14.71) | 34 | |

| > 15 | 27 (38.57) | 70 | < 0.0001 |

EMT Emergency medical technician

P-value is calculated by Chi Square test

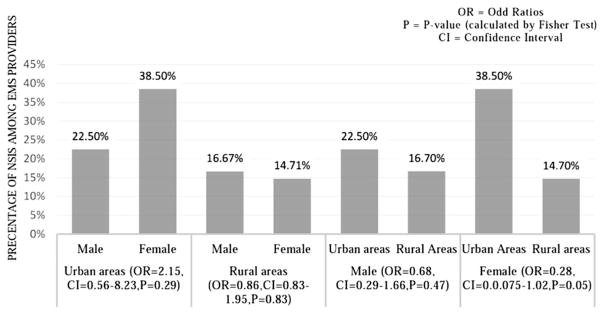

Stratification methods were performed to evaluate the relationship between residence and gender regarding NSIs. The figure shows gender and NSIs among stratified residence (urban and rural areas). There is quite varying proportion in NSIs between males (22.50%) and females (38.50%) in urban areas, with no statistically significant (OR 2.15, CI 0.56–8.23, P = 0.29). Likewise, there was no statistically significant relationship between gender and NSIs in rural areas (OR 0.86, CI 0.38–1.95, P = 0.83). Figure 1 also shows residence with NSIs among stratified gender. There was high varying proportion in NSIs between urban areas (38.50%) and rural areas (14.70%) among females (OR 0.28, CI 0.075–1.02, P = 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Stratification of gender and residence to evaluate the relationship with NSIs (n = 247)

Table 3 demonstrates an adjusted logistic regression for other variables. There were no variables shown significant association with NSIs, controlling the covariates.

Table 3.

Adjusted logistic regression modeling of NSIs (n = 247)

| Characteristic (Reference) | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | ||

| Female | 1.64 (0.71–3.75) | 0.23 |

| Residence (rural areas) | ||

| Urban areas | 1.81 (0.76–4.26) | 0.17 |

| Needlestick training (yes) | ||

| No | 1.83 (0.59–7.11) | 0.33 |

| Age (18–29) | ||

| 30–39 | 1.25 (0.35–4.49) | 0.72 |

| 40–49 | 0.70 (0.14–3.30) | 0.65 |

| 50–59 | 2.35 (0.44–12.10) | 0.31 |

| 60+ | 2.79 (0.26–30.31) | 0.38 |

| Employment status (full-time) | ||

| Part-time/volunteera | 0.41 (0.05–1.77) | 0.28 |

| Levels of certification (critical care paramedics) | ||

| Respondera/EMT-basic | 0.35 (0.10–1.18) | 0.09 |

| EMT-intermediate | 0.95 (0.15–4.78) | 0.95 |

| Paramedics | 1.16 (0.46–3.05) | 0.74 |

| Years of experience (< 5) | ||

| 6–10 | 0.82 (0.21–3.05) | 0.77 |

| 11–15 | 0.92 (0.18–4.72) | 0.92 |

| > 15 | 3.48 (0.78–17.76) | 0.11 |

OR Odd ratios, CI confidence interval

Merging (part-time with volunteer and responder with EMT-Basic due to low sample size)

Discussion

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) created prevention of bloodborne pathogen exposure and needlestick safety guidelines to protect HCWs, including EMS providers, from contracting infectious diseases [5, 21]. Although these efforts have resulted in well-grounded and defined regulations, EMS providers frequently are at risk of occupational injuries and illnesses [3, 4]. A probable and significant concern of such injuries that cause infectious diseases are NSIs [6, 7]. NSIs are the second-most route of exposure to blood after non-intact skin among EMS providers [22]. This study assessed the knowledge of EMS providers regarding NSIs and examined differences by demographics. In this study, 247 of 622 (39.7%) targeted EMS providers completed a cross-sectional survey. The majority of EMS providers (81.99%, n = 202) reported no NSI ever and 18.21% (n = 45) had at least one NSI within past 12 months (Table 1). This low proportion of NSIs among EMS providers is likely due to consistently compliance with standard precautions. Otherwise, they underestimated the risk of the NSIs, so they did not report them as significant to occupational injuries resulting in harmful diseases. A previous study observed that EMS providers only report NSIs when they seem at risk of transmission [23]. More specifically, EMS providers are most likely to report deep or moderate NSIs than those that are superficial [23].

In this study, we found that age and years of experience of EMS providers were associated with NSIs. Older and the more experienced EMS providers had more NSIs. They were most likely to underestimate the risk of NSIs, leading to the transmission of infectious diseases. Consequently, they inconsistently used standard precautions and became less self-protective over time. In contrast to a previous study, age and years of experience of EMS providers did not show any relationship with occupational exposures to blood in general [8]. In addition, they did not report the incidents as occupational injures [23]. We also found a relationship between levels of certification and NSIs, where the more certified EMS providers had more NSIs. Varied positions in the EMS system have differing levels of certifications and different job descriptions. Paramedics, who provide advanced emergency care to patients, may receive more exposure to blood than Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs), who provide basic emergency care [24]. Future research should investigate the cause of an increased rate of NSIs among experienced, old, and high-certified EMS providers.

EMS providers confront increased numbers of agitated patients, less sleep, and increased levels of tiredness in rural areas, which can have a negative impact on their safety performance [15, 16, 18]. In our study, urban EMS providers (26%) had slightly higher proportion of NSIs then rural EMS providers (16%), but this small difference does not show any relationship between residence and NSIs, nor between both areas. Furthermore, our findings generally showed no association between gender and NSIs, where no difference in proportion of NSIs was found between male and female EMS providers. However, Boal et al. found males are more often exposed to blood than females [8], although females considerably tended to report more occupational exposures than males [23]. Accordingly, when stratifying gender and residence based on NSIs, we found quite small varying of NSI occurrence between male and female in urban areas, where females had more NSIs than males. Also, this result is in contrast to Boal et al’s study, where males were often exposed to more blood than females, regardless of the place of residence [24]. On the other hand, there was large varying of NSI occurrence between urban areas (38.50%) and rural areas (14.70%) among females. This result indicates females are more prone to exposure to NSIs, specifically in urban areas. The results indicate a need to further examine NSIs and provide information regarding the safety precautions among urban and rural EMS providers. The results will help identify areas of possible improvement and show how to implement an effective program to prevent NSIs and other routes of exposure to blood in urban and rural areas.

This study has some limitations. The response rate of 47.31% created the potential for nonresponse bias, resulting in non-generalizable outcomes. For example, EMS providers who did not have NSIs tended to respond, and others who had NSIs may have been non-responsive to the survey. In addition, responders might have had recall bias because they might recall events that have occurred at one time, when they occurred at another time. Additionally, these results cannot necessarily be generalized directly to other EMS systems, as the study was limited to one state (West Virginia), and the results may not be applicable to other states. Finally, there was no way of categorizing all EMS agencies responded as urban or rural because some agencies include stations and squads in different locations.

Conclusion

A survey of NSIs among EMS providers indicates age and years of experience of EMS providers are associated with NSIs. Older, more experienced, and persons with a higher certification level report more NSIs in the previous 12 months. Future research should investigate the cause of an increased rate of NSIs among experienced, old, and high-certified EMS providers. The survey also indicates female EMS providers are more prone to exposure to blood through NSIs specifically in urban areas, but there is no indication of gender difference in rural areas regrading increased NSIs. The results indicate a need to further examine NSIs and provide information regarding the safety precautions among urban and rural EMS providers.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Hämäläinen P, Takala J, Saarela KL. Global estimates of fatal work-related diseases. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2007;50(1):28–41. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu XN, Sun XY, van Genugten L, Shi YH, Wang YL, Niu WY, Richardus JH. Occupational exposure to blood and compliance with standard precautions among health care workers in Beijing, China. American Journal of Infection Control. 2014;42(3):e37–e38. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heick R, Young T, Peek-Asa C. Occupational injuries among emergency medical service providers in the United States. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2009;51(8):963–968. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181af6b76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sayed ME, Kue R, McNeil C, Dyer KSA. Descriptive analysis of occupational health exposures in an urban emergency medical services system: 2007–2009. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2011;15(4):506–510. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2011.598608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagger J, Perry J, Gomaa A, Phillips EK. The impact of U.S. policies to protect Healthcare workers from blood-borne pathogens: The critical role of safety engineered devices. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2008;1(2):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garus-Pakowska A, Szatko F, Ulrichs M. Work-related accidents and sharp injuries in paramedics—Illustrated with an example of a multi-specialist hospital, located in Central Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;14(8):901. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yilmaz A, Serinken M, Dal O, Yaylacı S, Karcioglu O. Work-related injuries among emergency medical technicians in western Turkey. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2016;31(5):505–508. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X16000741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boal W, Leiss J, Ratcliffe J, Sousa S, Lyden J, Li J, Jagger J. The national study to prevent blood exposure in paramedics: Rates of exposure to blood. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2010;83(2):191–199. doi: 10.1007/s00420-009-0421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen GX, Jenkins EL. Potential work-related exposures to blood borne pathogens by industry and occupation in the United States part II: A telephone interview study. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2007;50:285–292. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leiss JK, Sousa S, Boal WL. Circumstances surrounding occupational blood exposure events in the National Study to prevent blood exposure in paramedics. Industrial Health. 2009;47(2):139–144. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.47.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Stop Sticks Campaign. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH); 2010. [Accessed 7 Oct 2017]. Last updated: September 28, 2010. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/stopsticks/bloodborne.html#HIV. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris AM, Iqbal K, Schillie S, Britton J, Kainer M, Tressler S, Vellozzi C. Increases in Acute Hepatitis B Virus Infections—Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, 2006–2013. CDC. 2016;65(3):47–50. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6503a2. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6503a2.htm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zibbell J, Iqbal K, Patel R, et al. Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged ≤ 30 years-Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006–2012. CDC. 2015;64(17):453–458. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6417a2.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngatu NR, Phillips EK, Wembonyama OS, Hirota R, Kaunge NJ, Mbutshu LH, Suganuma N. Practice of universal precautions and risk of occupational blood-borne viral infection among Congolese health care workers. American Journal of Infection Control. 2012;40(1):68. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pyper Z, Paterson JL. Fatigue and mental health in Australian rural and regional ambulance personnel. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2016;28(1):62–66. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gormley MA, Crowe RP, Bentley MA, Levine RA. National description of violence toward emergency medical services personnel. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2016;20(4):439–447. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2015.1128029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patterson PD, Suffoletto BP, Kupas DF, Weaver MD, Hostler D. Sleep quality and fatigue among prehospital providers. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2010;14(2):187–193. doi: 10.3109/10903120903524971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson PD, Weaver MD, Frank RC, et al. Association between poor sleep, fatigue, and safety outcomes in emergency medical services providers. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2012;16(1):86–97. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2011.616261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United States Census Bureau. [Accessed 7 October 2017];Urban and Rural. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/urban-rural.html.

- 20.Qualtrics. About Qualtrics. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.qualtrics.com/about-qualtrics/

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendation for prevention of HIV Transmission in Health-care settings. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1987;36(2):1–18. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00023587.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leiss JK, Ratcliffe JM, Lyden JT, Sousa S, Orelien JG, Boal WL, Jagger J. Blood exposure among paramedics: Incidence rates from the national study to prevent blood exposure in paramedics. Annals of epidemiology. 2006;16:720–725. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boal WL, Leiss JK, Sousa S, Lyden JT, Li J, Jagger J. The national study to prevent blood exposure in paramedics: Exposure reporting. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2008;51(3):213–222. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris SA, Nicolai LA. Occupational exposures in emergency medical service providers and knowledge of and compliance with universal precautions. AJIC: American Journal of Infection Control. 2010;38(2):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]