Abstract

Recent studies have found an association between functional variants in TREM2 and PLD3 and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but their effect on cognitive function is unknown. We examined the effect of these variants on cognitive function in 1,449 participants from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention, a longitudinal study of initially asymptomatic adults, age 36–73 at baseline, enriched for a parental history of AD. A comprehensive cognitive test battery was performed at up to five visits. A factor analysis resulted in six cognitive factors that were standardized into z scores (~N [0, 1]); the mean of these z scores was also calculated. In linear mixed models adjusted for age, gender, practice effects, and self-reported race/ethnicity, PLD3 V232M carriers had significantly lower mean z scores (p=0.02), and lower z scores for Story Recall (p=0.04), Visual Learning & Memory (p=0.049), and Speed & Flexibility (p=0.02) than non-carriers. TREM2 R47H carriers had marginally lower z scores for Speed & Flexibility (p=0.06). In conclusion, a functional variant in PLD3 was associated with significantly lower cognitive function in individuals carrying the variant than in non-carriers.

Keywords: TREM2, PLD3, family history, Alzheimer’s disease, memory, cognition, longitudinal

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60–80% of dementia cases. Over 5 million Americans have AD and that number is expected to increase to nearly 14 million by 2050 due to the projected increase in the number of older Americans (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016). AD is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States and the only of the top ten causes of death with no way to prevent, cure, or impede its progression (Alzheimer’s Association, 2013). There are currently few known risk factors that are highly predictive of AD. Individuals with a family history of AD are known to be at increased risk for developing the disease, and the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE) is also a well-established risk factor. Carrying one copy of the APOE ε4 allele results in a three-fold higher risk of developing AD than those with two copies of the more common ε3 allele, and those with two copies of the ε4 allele have an 8- to 12-fold higher risk (Holtzman, et al., 2012, Loy, et al., 2014).

Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 19 additional genetic regions that are associated with AD (Lambert, et al., 2013, Naj, et al., 2011). While potentially important for risk prediction, the genetic variants in these regions are of unknown function and have modest odds ratios (OR) ranging from 1.1 to 1.2 per risk allele. Moreover, these variants together explain a relatively small portion of the full genetic contribution to AD (Ridge, et al., 2013). GWAS have typically focused on common genetic variants, with minor allele frequencies ≥5%, as these were historically the types of variants included on genome-wide chips. However, recent sequencing studies have identified three functional low frequency (minor allele frequency 0.5–5%) variants with a more substantial effect (OR of approximately 2–5) on risk for AD: R47H in the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 gene (TREM2) [(Guerreiro, et al., 2012);(Jonsson, et al., 2012)], and V232M and A442A (splice site variant) in the phospholipase D family, member 3 gene (PLD3) (Cruchaga, et al., 2013). We sought to examine the effect of these variants on cognitive performance in a longitudinal study of middle-aged adults who were cognitively healthy at enrollment and enriched for a parental history of AD.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

Study participants were from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP), a longitudinal study of initially asymptomatic adults, age 36–73 at baseline, that allows for the enrollment of siblings and is enriched for a parental history of AD (i.e., a biological parent with either autopsy-confirmed AD, probable AD as defined by NINCDS-ADRDA research criteria (McKhann, et al., 1984), or dementia due to AD based on the Dementia Questionnaire (DQ) (Ellis, et al., 1998)). Details of the study design and methods have been previously described (Engelman, et al., 2014, La Rue, et al., 2008, Sager, et al., 2005). Baseline recruitment began in 2001 with initial follow up after four years and subsequent ongoing follow up every two years or until a participant receives a clinical diagnosis of AD, at which point they are no longer followed. Data from up to five study visits were available for the current analyses. A total of 1,449 WRAP participants had genotypic data for the low frequency variants analyzed in the current study. This study was conducted with the approval of the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board and all subjects provided signed informed consent before participation.

2.2. Neuropsychological assessment

The WRAP cognitive test battery assesses many domains and has been previously described (Darst, et al., 2015, Sager, et al., 2005). For these analyses, we used one composite variable estimating cognitive functioning at age 54 (the mean age at baseline) and six factor scores representing longitudinal functioning across memory and executive function domains.

2.2.1. Composite Progression Score

A composite index, named progression score (PS), was computed using a set of eight cognitive measures, including Trails A and B (Reitan and Wolfson, 1985), Digit Span Forward and Digit Span Backward (Wechsler, 1997), Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) summed score across five learning trials (Lezak, et al., 2004), AVLT delayed recall (Lezak, et al., 2004), Boston Naming Test (Kaplan, et al., 1983), and the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein, et al., 1975). Visits with fewer than four of these measurements were excluded. We applied the PS model (Bilgel, et al., 2015, Jedynak, et al., 2012) to align individuals along a linear cognitive trajectory based on their longitudinal cognitive measure profiles, adjusting for inter-individual differences in rates of change, with a higher PS indicating greater overall cognitive decline across the eight measures. We accounted for correlations among cognitive measures and constrained the progression scores to increase linearly with age within each individual. To remove confounding effects of age at entry into WRAP, the progression score was estimated at age 54, the mean age at baseline.

2.2.2. Longitudinal Factor Scores

A factor analysis of the neuropsychological test scores was performed as described previously (Dowling, et al., 2010, Jonaitis, et al., 2015, Koscik, et al., 2014). The resulting factor scores were standardized into z scores (~N [0, 1]), using means and standard deviations obtained from the whole sample at baseline (visit 1) or visit 2 for a subset of tests that were first administered at this visit. There were four cognitive factor z scores for memory (Immediate Memory, Verbal Learning & Memory, Story Recall, and Visual Learning & Memory) and two for executive function (Working Memory and Speed & Flexibility). Tests comprising each of these factors have been previously described (Darst, et al., 2015). Due to the small number of individuals carrying the functional variants, these six factor scores were also averaged to create a summary cognitive measure of the factor scores for each individual. Consequently, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons when examining the mean z score and used the individual cognitive factor scores to inform which domains were driving the association with the mean z score.

2.3 DNA Collection, Genotyping, and Quality Control

DNA was extracted from whole blood samples as described previously (Engelman, et al., 2013). Genotyping of the TREM2 variant R47H (rs75932628) and PLD3 variants V232M (rs145999145) and A442A (rs4819; splice site variant) was performed using competitive allele-specific PCR based KASP™ genotyping assays (LGC Genomics, Beverly, MA). The quality control process has been described previously (Darst, et al., 2016). The PLD3 splice site variant, A442A, was monomorphic in our sample. Consequently, no genetic association analysis could be performed on this variant. The other PLD3 variant and the TREM2 variant were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Differences in allele frequencies between those with a parental history of AD and those without were tested using a Fisher’s exact test. TREM2 and PLD3 associations with each of the cognitive factor scores and the PS at age 54 were tested using linear mixed models (SAS PROC MIXED) by comparing carriers of one of the rare variants to non-carriers of either. For each cognitive factor score, models included fixed effects for age, gender, practice effects, and self-reported race/ethnicity and random effects for family (siblings) and participant (repeated measures). For the PS, the model included fixed effects for gender and race/ethnicity (age was not adjusted for as it was used to calculate the PS) and a random effect for family. To visually display the cognitive factor z scores, adjusted mean z scores (a weighted average of the predicted z scores across all classes of gender and race/ethnicity, and for the average age) were calculated and plotted for TREM2 R47H and PLD3 V232M carriers, as well as for APOE ε4 homozygotes, ε4 heterozygotes, and non-carriers of any of these three risk variants, using the LSMEANS statement in PROC MIXED with the OM option to weight the average of the predictions to be proportionate to the input data set. This was especially important for race/ethnicity, which was not evenly distributed in the WRAP cohort. All analyses were performed in SAS v9.4 and used a p value threshold of < 0.05 to determine significance.

3. Results

Characteristics of the 1,449 participants, according to TREM2 and PLD3 carrier status, are shown in Table 1. No participants carried both the TREM2 R47H (T allele) and PLD3 V232M (A allele) low frequency variants. There were no significant (p < 0.05) differences in the characteristics between carriers of either variant and non-carriers. Of the 16 participants who carried the TREM2 variant, 15 were non-Hispanic Caucasian, 1 was Hispanic, and none were African American or another race/ethnicity. All 13 PLD3 carriers were non-Hispanic Caucasian.

Table 1.

WRAP Participant Characteristics at Baseline, Mean (SD) or n (%)

| Characteristic |

TREM2 (R47H) Carriera (n=16) |

PLD3 (V232M) Carriera (n=13) |

Non-carrier (n=1,413) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 52.4 (5.6) | 51.8 (8.9) | 53.8 (6.6) |

| Gender (female) | 13 (81.3) | 10 (76.9) | 898 (70.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 15 (93.8) | 13 (100.0) | 1,253 (88.8) |

| African American | 0 | 0 | 113 (8.0) |

| Hispanic | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 33 (2.3) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 12 (0.9) |

| Years of Education | 15.3 (2.8) | 15.7 (3.1) | 16.2 (2.3) |

| APOE Genotype | |||

| ε2/ε2 | 0 | 0 | 5 (0.4) |

| ε2/ε3 | 1 (6.3) | 3 (23.1) | 113 (8.0) |

| ε2/ε4 | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 46 (3.3) |

| ε3/ε3 | 6 (37.5) | 4 (30.8) | 742 (52.5) |

| ε3/ε4 | 7 (43.8) | 6 (46.2) | 447 (31.6) |

| ε4/ε4 | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 60 (4.2) |

No participants carried both the TREM2 and PLD3 variants; seven participants had a missing genotype for either TREM2 or PLD3 and are not included in this table. Minor/risk allele for TREM2 R47H was T; minor/risk allele for PLD3 V232M was A.

Presence of the TREM2 R47H variant was associated with AD parental history status; all sixteen participants with R47H were in the parental history group (Table 2). Patterns appeared similar for the relationship between PLD3 V232M and AD parental history.

Table 2.

Carrier Frequency (n) by Parental History of AD

| Gene (variant) | No parent with AD (n=409) | Parent with AD (n=1040) | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| TREM2 (R47H) | 0.00 (0) | 0.015 (16) | 0.009 |

| PLD3 (V232M) | 0.005 (2) | 0.011 (11) | 0.54 |

Fisher’s exact test of the difference in allele frequency in individuals without versus with a parent with AD.

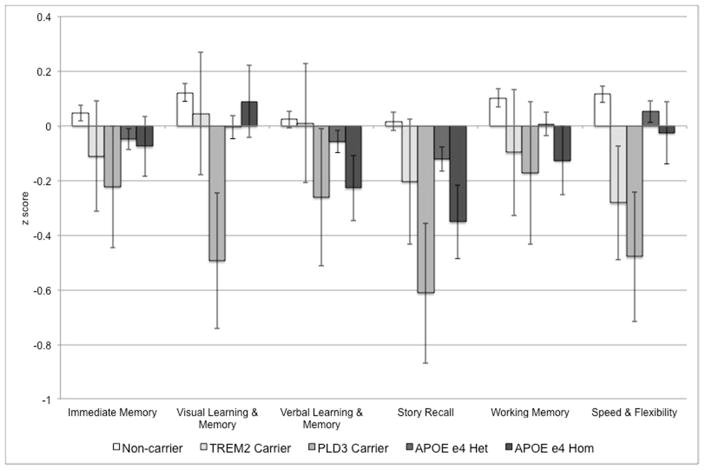

In linear mixed models, PLD3 carriers had significantly lower mean z scores, and lower z scores for Story Recall, Visual Learning & Memory, and Speed & Flexibility than non-carriers (Table 3; results for APOE ε4 count are shown for comparison). TREM2 carriers had marginally lower z scores for Speed & Flexibility (p = 0.06). While the PS at age 54 was higher for both TREM2 and PLD3 carriers, indicating greater disease progression, these differences were not statistically significant. Adjusted mean z scores for the six cognitive factors for TREM2 carriers, PLD3 carriers, as well as for APOE ε4 homozygotes, ε4 heterozygotes, and non-carriers of any of these three risk variants are shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Association Between Risk Variant and Cognitive Function

| Cognitive Function | β ± SE (p value)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

TREM2 (R47H) (n=1,446) |

PLD3 (V232M) (n=1,445) |

APOE ε4 count | |

| Composite Progression Score | |||

| Progression Score at age 54a | 0.19 ± 0.29 (0.52) | 0.46 ± 0.33 (0.16) | 0.11 ± 0.05 (0.04) |

| Longitudinal Factor Scores | |||

| Mean of six Factor Scores | −0.14 ± 0.16 (0.38) | −0.41 ± 0.18 (0.02) | −0.10 ± 0.03 (0.002) |

| Immediate Memory | −0.12 ± 0.20 (0.56) | −0.23 ± 0.23 (0.32) | −0.07 ± 0.04 (0.06) |

| Verbal Learning & Memory | −0.002 ± 0.22 (0.99) | −0.22 ± 0.25 (0.37) | −0.09 ± 0.04 (0.03) |

| Story Recall | −0.16 ± 0.24 (0.49) | −0.55 ± 0.26 (0.04) | −0.14 ± 0.05 (0.002) |

| Visual Learning & Memory | −0.06 ± 0.22 (0.78) | −0.49 ± 0.25 (0.049) | −0.08 ± 0.04 (0.05) |

| Working Memory | −0.15 ± 0.23 (0.51) | −0.26 ± 0.27 (0.34) | −0.11 ± 0.04 (0.01) |

| Speed & Flexibility | −0.39 ± 0.20 (0.06) | −0.54 ± 0.24 (0.02) | −0.06 ± 0.04 (0.11) |

Linear mixed model, adjusting for age, gender, practice effects, and race/ethnicity, and accounting for within-family (sibling) correlations and within-individual correlations from up to 10 years of follow up.

Linear mixed model, adjusting for gender and race/ethnicity, and accounting for within-family (sibling) correlations.

Figure 1. Mean Adjusted Cognitive Function by Risk Allele Carrier Status.

Adjusted (for age, gender, practice effects, and race/ethnicity) mean z scores for the six cognitive factors for TREM2 R47H (T allele) carriers (light gray), PLD3 V232M (A allele) carriers (medium gray), APOE ε4 heterozygotes (dark gray), APOE ε4 homozygotes (very dark gray), and non-carriers of any of these three risk variants (white). Z scores were standardized (~N [0, 1]), using means and standard deviations obtained from the whole sample at baseline. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

4. Discussion

Functional low frequency variants in TREM2 are established risk factors for AD and an additional variant in PLD3 has been reported (Cruchaga, et al., 2013), but their effect on cognitive function in the years prior to the typical onset of AD is unknown. We examined the effect of these variants on cognitive performance in a longitudinal study of middle-aged adults who were cognitively healthy at enrollment, the majority of whom had a parental history of AD. The TREM2 R47H variant was found in 15 non-Hispanic Caucasians and 1 Hispanic, all with a parent who had AD. The PLD3 V232M variant was only found in non-Hispanic Caucasians and was twice as common in individuals with a parental history of AD than in those without a parental history. Although both variants were generally associated with lower cognitive function in carriers of either variant than in non-carriers, only carriers of the PLD3 variant had significantly lower cognitive function than non-carriers.

Our study population was intentionally enriched for individuals with a parental history of AD (72% of participants). While the carrier percentages in the parental history group were 1.5% for TREM2 R47H (T allele) and 1.1% for PLD3 V232M (A allele), the percentages in the participants with no parental history of AD were 0% and 0.5%, respectively. The TREM2 R47H carrier percentage is 0.4% in the Exome Aggregation Consortium database (ExAC; N = 60,145; accessed 11/15/16) (Lek, et al., 2016) and 0.5% in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD; N = 140,485; beta mode available at http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org; accessed 11/15/16; includes samples from the Alzheimer’s Disease Sequencing Project and from ExAC). The PLD3 V232M carrier percentage was 0.6% in ExAC (N = 57,683) and 0.7% in gnomAD (N = 141,023). Taken together, for both variants, the percent of individuals carrying the low frequency risk variant was higher in WRAP participants with a parental history of AD than in WRAP participants without a family history or in publicly available reference databases, illustrating the statistical power to be gained from a study design focusing on individuals with a family history of AD, in which low frequency risk variants are likely to be more prevalent.

Our cohort is 89% non-Hispanic Caucasian, with only 113 African Americans and 34 Hispanics, however, despite these small sample sizes, we did observe one Hispanic carrier of the TREM2 R47H variant. In gnomAD, the largest compilation of large-scale sequencing projects, the TREM2 R47H (T allele) was carried by 0.7% of Latinos (n = 18,221), 0.5% of Europeans (non-Finnish; n = 62,674), and 0.1% of Africans (n = 12,921). This higher carrier frequency in Latinos and lower carrier frequency in Africans is consistent with our observation. Moreover, our lack of PLD3 V232M (A allele) carriers in any group other than non-Hispanic Caucasian is not surprising given that the carrier percentage in gnomAD for this variant is 2.5 to 5 times higher for Europeans (non-Finnish; 1%) than for Latinos (0.4%) or Africans (0.2%).

PLD3 V232M carriers (six of whom were APOE ε4 heterozygotes [Table 1]) had least square mean (predicted) cognitive z scores that were lower than both APOE ε4 heterozygotes and homozygotes across all six cognitive factors (Figure 1). This suggests that the effect of the PLD3 V232M variant on cognition may be even stronger than carrying two copies of the APOE ε4 allele. However, this requires replication in other longitudinal studies of cognitive function.

Although our findings show consistency across multiple cognitive factors, many of our findings were not statistically significant, and those that were would not survive a correction for multiple testing. This is likely due to the rarity of the variants assessed, but could also be because our relatively young (early 50’s at baseline) population may not yet have experienced enough cognitive decline. It will be crucial to validate these findings with an external population, particularly one that has a larger number of carriers for these rare variants. Further, in order to determine how these variants influence the pathology of AD, it will also be essential to evaluate their influence on β-amyloid and tau, as the accumulation of both occurs long before an AD diagnosis.

In conclusion, our results support previous findings that show an increased AD risk in carriers of low frequency functional variants in TREM2 and PLD3 by suggesting that these variants may also be associated with lower cognitive function, likely due to an AD trajectory. This is particularly notable for the rare PLD3 variant, which is a less established AD risk factor. While these functional variants are found at low frequencies in the population, their effect on risk for AD is much larger than common variants found through GWAS. In fact, their effect on cognition may be similar to, if not greater than, that of the APOE ε4 allele. Further research is necessary in order to assess the influence of these rare variants on other crucial neurological changes such as the accumulation of β-amyloid and tau that are biomarkers of AD pathology.

Highlights.

3–5 must be included, 85 character max including spaces/highlight, only core results covered

Those with a parental history of AD more commonly carried PLD3 V232M or TREM2 R47H.

Carriers of PLD3 V232M had significantly lower mean z scores and lower z scores for Story Recall, Visual Learning & Memory, and Speed & Flexibility than non-carriers.

Cognitive effects of PLD3 V232M or TREM2 R47H may be similar to or greater than APOE

Acknowledgments

The WRAP program is funded by National Institute on Aging grants 5R01-AG27161-2 (Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention: Biomarkers of Preclinical AD) and R01-AG054047-01 (Genomic and Metabolomic Data Integration in a Longitudinal Cohort at Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease), the Helen Bader Foundation, Northwestern Mutual Foundation, Extendicare Foundation, and the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant UL1-TR000427. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging. BFD was supported by an NLM training grant to the Computation and Informatics in Biology and Medicine Training Program grant NLM 5T15LM007359. Computational resources were supported by a core grant to the Center for Demography and Ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (P2C HD047873).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

The data in the submitted manuscript have not been previously published, are not submitted elsewhere for consideration for publication, and will not be submitted elsewhere while under consideration at Neurobiology of Aging.

This study was conducted with the approval of the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board and all subjects provided signed informed consent before participation.

All authors have reviewed the contents of the manuscript being submitted and approve of its contents and validate the accuracy of the data.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2013;9(2):208–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(4):459–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgel M, Jedynak B, Wong DF, Resnick SM, Prince JL. Temporal Trajectory and Progression Score Estimation from Voxelwise Longitudinal Imaging Measures: Application to Amyloid Imaging. Information processing in medical imaging: proceedings of the conference. 2015;24:424–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-19992-4_33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruchaga C, Karch CM, Jin SC, Benitez BA, Cai Y, Guerreiro R, Harari O, Norton J, Budde J, Bertelsen S, Jeng AT, Cooper B, Skorupa T, Carrell D, Levitch D, Hsu S, Choi J, Ryten M, Hardy J, Trabzuni D, Weale ME, Ramasamy A, Smith C, Sassi C, Bras J, Gibbs JR, Hernandez DG, Lupton MK, Powell J, Forabosco P, Ridge PG, Corcoran CD, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Munger RG, Schmutz C, Leary M, Demirci FY, Bamne MN, Wang X, Lopez OL, Ganguli M, Medway C, Turton J, Lord J, Braae A, Barber I, Brown K, Passmore P, Craig D, Johnston J, McGuinness B, Todd S, Heun R, Kolsch H, Kehoe PG, Hooper NM, Vardy ER, Mann DM, Pickering-Brown S, Kalsheker N, Lowe J, Morgan K, David Smith A, Wilcock G, Warden D, Holmes C, Pastor P, Lorenzo-Betancor O, Brkanac Z, Scott E, Topol E, Rogaeva E, Singleton AB, Kamboh MI, St George-Hyslop P, Cairns N, Morris JC, Kauwe JS, Goate AM. Rare coding variants in the phospholipase D3 gene confer risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darst BF, Koscik RL, Hermann BP, La Rue A, Sager MA, Johnson SC, Engelman CD. Heritability of Cognitive Traits Among Siblings with a Parental History of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015 doi: 10.3233/JAD-142658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darst BF, Koscik RL, Racine AM, Oh JM, Krause RA, Carlsson CM, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Christian BT, Bendlin BB, Okonkwo OC, Hogan KJ, Hermann BP, Sager MA, Asthana S, Johnson SC, Engelman CD. Pathway-Specific Polygenic Risk Scores as Predictors of Amyloid-beta Deposition and Cognitive Function in a Sample at Increased Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016 doi: 10.3233/JAD-160195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling NM, Hermann B, La Rue A, Sager MA. Latent structure and factorial invariance of a neuropsychological test battery for the study of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2010;24(6):742–56. doi: 10.1037/a0020176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Jan K, Kawas C, Koller WC, Lyons KE, Jeste DV, Hansen LA, Thal LJ. Diagnostic validity of the dementia questionnaire for Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology. 1998;55(3):360–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman CD, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, Hermann BP, La Rue A, Sager MA. Investigation of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 variant in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. Neurobiology of aging. 2014;35(6):1252–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman CD, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, Okonkwo OC, Hermann BP, La Rue A, Sager MA. Interaction Between Two Cholesterol Metabolism Genes Influences Memory: Findings from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013 doi: 10.3233/JAD-130482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of psychiatric research. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, Cruchaga C, Sassi C, Kauwe JS, Younkin S, Hazrati L, Collinge J, Pocock J, Lashley T, Williams J, Lambert JC, Amouyel P, Goate A, Rademakers R, Morgan K, Powell J, St George-Hyslop P, Singleton A, Hardy J. TREM2 Variants in Alzheimer’s Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman DM, Herz J, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and apolipoprotein E receptors: normal biology and roles in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(3):a006312. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedynak BM, Lang A, Liu B, Katz E, Zhang Y, Wyman BT, Raunig D, Jedynak CP, Caffo B, Prince JL Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging, I. A computational neurodegenerative disease progression score: method and results with the Alzheimer’s disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort. NeuroImage. 2012;63(3):1478–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonaitis EM, Koscik RL, La Rue A, Johnson SC, Hermann BP, Sager MA. Aging, Practice Effects, and Genetic Risk in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. Clin Neuropsychol. 2015;29(4):426–41. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2015.1047407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson T, Stefansson H, PhDS, Jonsdottir I, Jonsson PV, Snaedal J, Bjornsson S, Huttenlocher J, Levey AI, Lah JJ, Rujescu D, Hampel H, Giegling I, Andreassen OA, Engedal K, Ulstein I, Djurovic S, Ibrahim-Verbaas C, Hofman A, Ikram MA, van Duijn CM, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Stefansson K. Variant of TREM2 Associated with the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston naming test. Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Koscik RL, La Rue A, Jonaitis EM, Okonkwo OC, Johnson SC, Bendlin BB, Hermann BP, Sager MA. Emergence of mild cognitive impairment in late middle-aged adults in the wisconsin registry for Alzheimer’s prevention. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;38(1–2):16–30. doi: 10.1159/000355682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rue A, Hermann B, Jones JE, Johnson S, Asthana S, Sager MA. Effect of parental family history of Alzheimer’s disease on serial position profiles. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(4):285–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, Jun G, Destefano AL, Bis JC, Beecham GW, Grenier-Boley B, Russo G, Thornton-Wells TA, Jones N, Smith AV, Chouraki V, Thomas C, Ikram MA, Zelenika D, Vardarajan BN, Kamatani Y, Lin CF, Gerrish A, Schmidt H, Kunkle B, Dunstan ML, Ruiz A, Bihoreau MT, Choi SH, Reitz C, Pasquier F, Hollingworth P, Ramirez A, Hanon O, Fitzpatrick AL, Buxbaum JD, Campion D, Crane PK, Baldwin C, Becker T, Gudnason V, Cruchaga C, Craig D, Amin N, Berr C, Lopez OL, De Jager PL, Deramecourt V, Johnston JA, Evans D, Lovestone S, Letenneur L, Moron FJ, Rubinsztein DC, Eiriksdottir G, Sleegers K, Goate AM, Fievet N, Huentelman MJ, Gill M, Brown K, Kamboh MI, Keller L, Barberger-Gateau P, McGuinness B, Larson EB, Green R, Myers AJ, Dufouil C, Todd S, Wallon D, Love S, Rogaeva E, Gallacher J, St George-Hyslop P, Clarimon J, Lleo A, Bayer A, Tsuang DW, Yu L, Tsolaki M, Bossu P, Spalletta G, Proitsi P, Collinge J, Sorbi S, Sanchez-Garcia F, Fox NC, Hardy J, Naranjo MC, Bosco P, Clarke R, Brayne C, Galimberti D, Mancuso M, Matthews F, Moebus S, Mecocci P, Del Zompo M, Maier W, Hampel H, Pilotto A, Bullido M, Panza F, Caffarra P, Nacmias B, Gilbert JR, Mayhaus M, Lannfelt L, Hakonarson H, Pichler S, Carrasquillo MM, Ingelsson M, Beekly D, Alvarez V, Zou F, Valladares O, Younkin SG, Coto E, Hamilton-Nelson KL, Gu W, Razquin C, Pastor P, Mateo I, Owen MJ, Faber KM, Jonsson PV, Combarros O, O’Donovan MC, Cantwell LB, Soininen H, Blacker D, Mead S, Mosley TH, Jr, Bennett DA, Harris TB, Fratiglioni L, Holmes C, de Bruijn RF, Passmore P, Montine TJ, Bettens K, Rotter JI, Brice A, Morgan K, Foroud TM, Kukull WA, Hannequin D, Powell JF, Nalls MA, Ritchie K, Lunetta KL, Kauwe JS, Boerwinkle E, Riemenschneider M, Boada M, Hiltunen M, Martin ER, Schmidt R, Rujescu D, Wang LS, Dartigues JF, Mayeux R, Tzourio C, Hofman A, Nothen MM, Graff C, Psaty BM, Jones L, Haines JL, Holmans PA, Lathrop M, Pericak-Vance MA, Launer LJ, Farrer LA, van Duijn CM, Van Broeckhoven C, Moskvina V, Seshadri S, Williams J, Schellenberg GD, Amouyel P. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature genetics. 2013;45(12):1452–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Ware JS, Hill AJ, Cummings BB, Tukiainen T, Birnbaum DP, Kosmicki JA, Duncan LE, Estrada K, Zhao F, Zou J, Pierce-Hoffman E, Berghout J, Cooper DN, Deflaux N, DePristo M, Do R, Flannick J, Fromer M, Gauthier L, Goldstein J, Gupta N, Howrigan D, Kiezun A, Kurki MI, Moonshine AL, Natarajan P, Orozco L, Peloso GM, Poplin R, Rivas MA, Ruano-Rubio V, Rose SA, Ruderfer DM, Shakir K, Stenson PD, Stevens C, Thomas BP, Tiao G, Tusie-Luna MT, Weisburd B, Won HH, Yu D, Altshuler DM, Ardissino D, Boehnke M, Danesh J, Donnelly S, Elosua R, Florez JC, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Glatt SJ, Hultman CM, Kathiresan S, Laakso M, McCarroll S, McCarthy MI, McGovern D, McPherson R, Neale BM, Palotie A, Purcell SM, Saleheen D, Scharf JM, Sklar P, Sullivan PF, Tuomilehto J, Tsuang MT, Watkins HC, Wilson JG, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG Exome Aggregation, C. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536(7616):285–91. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak M, Howieson D, Loring D. Neuropsychological Assessment. 4. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Loy CT, Schofield PR, Turner AM, Kwok JB. Genetics of dementia. Lancet. 2014;383(9919):828–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60630-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naj AC, Jun G, Beecham GW, Wang LS, Vardarajan BN, Buros J, Gallins PJ, Buxbaum JD, Jarvik GP, Crane PK, Larson EB, Bird TD, Boeve BF, Graff-Radford NR, De Jager PL, Evans D, Schneider JA, Carrasquillo MM, Ertekin-Taner N, Younkin SG, Cruchaga C, Kauwe JS, Nowotny P, Kramer P, Hardy J, Huentelman MJ, Myers AJ, Barmada MM, Demirci FY, Baldwin CT, Green RC, Rogaeva E, St George-Hyslop P, Arnold SE, Barber R, Beach T, Bigio EH, Bowen JD, Boxer A, Burke JR, Cairns NJ, Carlson CS, Carney RM, Carroll SL, Chui HC, Clark DG, Corneveaux J, Cotman CW, Cummings JL, DeCarli C, DeKosky ST, Diaz-Arrastia R, Dick M, Dickson DW, Ellis WG, Faber KM, Fallon KB, Farlow MR, Ferris S, Frosch MP, Galasko DR, Ganguli M, Gearing M, Geschwind DH, Ghetti B, Gilbert JR, Gilman S, Giordani B, Glass JD, Growdon JH, Hamilton RL, Harrell LE, Head E, Honig LS, Hulette CM, Hyman BT, Jicha GA, Jin LW, Johnson N, Karlawish J, Karydas A, Kaye JA, Kim R, Koo EH, Kowall NW, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Lieberman AP, Lopez OL, Mack WJ, Marson DC, Martiniuk F, Mash DC, Masliah E, McCormick WC, McCurry SM, McDavid AN, McKee AC, Mesulam M, Miller BL, Miller CA, Miller JW, Parisi JE, Perl DP, Peskind E, Petersen RC, Poon WW, Quinn JF, Rajbhandary RA, Raskind M, Reisberg B, Ringman JM, Roberson ED, Rosenberg RN, Sano M, Schneider LS, Seeley W, Shelanski ML, Slifer MA, Smith CD, Sonnen JA, Spina S, Stern RA, Tanzi RE, Trojanowski JQ, Troncoso JC, Van Deerlin VM, Vinters HV, Vonsattel JP, Weintraub S, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Williamson J, Woltjer RL, Cantwell LB, Dombroski BA, Beekly D, Lunetta KL, Martin ER, Kamboh MI, Saykin AJ, Reiman EM, Bennett DA, Morris JC, Montine TJ, Goate AM, Blacker D, Tsuang DW, Hakonarson H, Kukull WA, Foroud TM, Haines JL, Mayeux R, Pericak-Vance MA, Farrer LA, Schellenberg GD. Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nature genetics. 2011;43(5):436–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead–Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Therapy and clinical interpretation. Neuropsychological Press; Tucson, AZ: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ridge PG, Mukherjee S, Crane PK, Kauwe JS Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics, C. Alzheimer’s disease: analyzing the missing heritability. PloS one. 2013;8(11):e79771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager MA, Hermann B, La Rue A. Middle-aged children of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: APOE genotypes and cognitive function in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology. 2005;18(4):245–9. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1997. [Google Scholar]