Abstract

Purpose

The CIGMA study investigated a novel human polyclonal antibody preparation (trimodulin) containing ~ 23% immunoglobulin (Ig) M, ~ 21% IgA, and ~ 56% IgG as add-on therapy for patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia (sCAP).

Methods

In this double-blind, phase II study (NCT01420744), 160 patients with sCAP requiring invasive mechanical ventilation were randomized (1:1) to trimodulin (42 mg IgM/kg/day) or placebo for five consecutive days. Primary endpoint was ventilator-free days (VFDs). Secondary endpoints included 28-day all-cause and pneumonia-related mortality. Safety and tolerability were monitored. Exploratory post hoc analyses were performed in subsets stratified by baseline C-reactive protein (CRP; ≥ 70 mg/L) and/or IgM (≤ 0.8 g/L).

Results

Overall, there was no statistically significant difference in VFDs between trimodulin (mean 11.0, median 11 [n = 81]) and placebo (mean 9.6; median 8 [n = 79]; p = 0.173). Twenty-eight-day all-cause mortality was 22.2% vs. 27.8%, respectively (p = 0.465). Time to discharge from intensive care unit and mean duration of hospitalization were comparable between groups. Adverse-event incidences were comparable. Post hoc subset analyses, which included the majority of patients (58–78%), showed significant reductions in all-cause mortality (trimodulin vs. placebo) in patients with high CRP, low IgM, and high CRP/low IgM at baseline.

Conclusions

No significant differences were found in VFDs and mortality between trimodulin and placebo groups. Post hoc analyses supported improved outcome regarding mortality with trimodulin in subsets of patients with elevated CRP, reduced IgM, or both. These findings warrant further investigation.

Trial registration: NCT01420744.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00134-018-5143-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Trimodulin, Polyclonal antibody, Severe community-acquired pneumonia, Add-on therapy, Immunoglobulin M

Take-home message

| In mechanically ventilated patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia, add-on therapy with trimodulin, a novel polyclonal antibody preparation, did not statistically significantly increase ventilator-free days (primary endpoint) vs. placebo. Exploratory post hoc analyses suggest reductions in mortality for trimodulin compared with placebo in subsets of patients with elevated C-reactive protein levels and/or reduced immunoglobulin M levels, and warrant investigation in a phase III study with a targeted patient population. |

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) has an incidence of ~ 1.2 per 1000 persons per year in Europe, varying with region, age, and comorbidities [1]. Up to 21% of hospitalized patients with CAP are admitted to intensive care units (ICUs), thus impacting healthcare costs and clinical outcomes [2]. Severe CAP (sCAP), usually defined as CAP that requires treatment in an ICU, is associated with high mortality of up to 58% [3].

Antibiotic therapy with supportive care alone has limited success in sCAP; hence, targeting inflammatory responses may improve patient outcomes. This approach is supported by the observation that a systemic and complex cytokine response (interleukin-6 and -10) is linked to greater mortality in patients with CAP, irrespective of the presence of sepsis [4]. Further, therapeutic response and treatment outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome may be worse in patients with a hyperinflammatory disease phenotype [5]. A recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor, activated protein C, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins (Igs), and intravenous IgM-enriched Igs have been investigated for their potential as add-on therapies targeted at the immune response in patients with sCAP [6–9].

IgM plays a critical role in the immediate defense against severe bacterial infection. Reduced IgM levels have been observed in patients with CAP, sepsis, and severe pandemic influenza; consequently, interest in add-on therapy with IgM-enriched preparations has increased [10–12]. The evidence for IgM-enriched Ig preparations in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock is incompletely understood, although systematic reviews have generally concluded that IgM-enriched Ig preparations are associated with a reduction in mortality [6, 7]. Relevant mechanisms of action include opsonization of causal pathogens, neutralization of microbial pathogens and virulence factors, and modulation of the inflammatory response [13–15].

Trimodulin is a novel human plasma-derived native polyclonal antibody preparation for intravenous administration [16, 17]. Trimodulin contains IgM (~ 23%), IgA (~ 21%), and IgG (~ 56%).

The CIGMA (Concentrated IgM for Application) study reported here aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of trimodulin as an add-on therapy in patients with sCAP requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV).

Methods

Study design and patient population

The CIGMA study (NCT01420744 [18, 19]), a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter, parallel-group, phase II trial, was conducted in hospitals in Germany, Spain, and the UK. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation, Good Clinical Practice standards, and the Declaration of Helsinki, and with local institutional review board/independent ethics committee approval. All patients (or their representatives) provided written informed consent.

Patients ≥ 18 years of age with sCAP (diagnosed clinically and radiologically), requiring IMV and receiving standard antibiotics, were enrolled. Patients with suspected hospital-acquired pneumonia; severe lung diseases interfering with sCAP therapy (e.g., cystic fibrosis); life expectancy of ≤ 28 days due to medical conditions not related to sCAP or to sCAP-associated sepsis; selective, absolute IgA deficiency with antibodies to IgA, neutrophil count < 1000/mm3; or platelet count < 50,000/mm3 were excluded. Study-specific guidance on IMV, weaning procedures based on the concept of lung-protective ventilation, and on antibiotic treatment according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of CAP in adults was provided to minimize potential differences among sites and countries [18, 20].

Eligible patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either trimodulin (5% protein solution; BT086; Biotest AG, Dreieich, Germany) or an equal volume of human albumin as placebo (1% protein solution), both as intravenous infusion. Dosing of trimodulin based on IgM content (42 mg IgM/kg body weight) or placebo was once daily for five consecutive days. Infusion was initiated ≥ 1 and ≤ 12 h following commencement of IMV at a rate of 0.1 mL/min, increasing by 0.1 mL every 10 min to a maximum of 0.5 mL/min (target infusion rate).

Patients were followed until day 28 or hospital discharge, whichever occurred first (with an additional safety follow-up visit at day 43 in the UK). Mortality was followed up until day 28 in discharged patients.

Patients were assigned a unique randomization number generated by Accovion GmbH (Eschborn, Germany; now Clinipace Worldwide, Morrisville, North Carolina, USA) using Rando® and recorded by the investigator. Randomization numbers were grouped in blocks of four to facilitate equal distribution into the two groups. Blinding was maintained by a similar appearance of placebo to trimodulin, and vials were covered with transparent colored foil.

Pathogen detection was performed according to local standards, with sputum and blood cultures being the most frequently analyzed, followed by smear and bronchoalveolar lavage.

Efficacy assessments

The primary endpoint was ventilator-free days (VFDs), defined as the number of days between extubation from IMV to day 28 after enrollment. VFDs were set to “0” if the patient died before day 28 or required IMV for ≥ 28 days [21].

Secondary endpoints included 28-day all-cause mortality, 28-day investigator-determined pneumonia-related mortality, time from admission to discharge from the ICU, time from hospital admission to discharge, change in Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (measured on days 1 and 28), and days free from inotrope/vasopressor (dobutamine, epinephrine, dopamine, or norepinephrine).

Safety

Safety was assessed throughout the trial, with events classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 17.1. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs; defined as an adverse event [AE] that occurred from the time of first dose of study medication until the final follow-up visit, independent of relation to study drug), infusion-related reactions (defined as TEAEs that occurred during or within 24 h after infusion of study medication), vital signs, electrocardiograms, and laboratory parameters including clinical chemistry, hematology, and coagulation were recorded. Renal function was monitored through serum creatinine. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated post hoc using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation considering serum creatinine, age, gender, and race [22]. An independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) closely monitored the first six sequentially enrolled patients. The DSMB also reviewed unblinded safety data of patients during the course of the study.

Statistical analysis

All statistical methods, unless otherwise specified, were prespecified in the study protocol.

A group-sequential adaptive design was chosen that allowed modifications, such as sample size re-estimation or planning of further analyses based on interim results. After the first of two interim analyses, the sample size was adjusted to 160 patients [18].

VFDs were evaluated using a one-sided Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test with an α level of 0.025. Twenty-eight-day all-cause mortality was evaluated using the Kaplan–Meier method and analyzed using a Mantel–Haenszel test. The study was powered to detect a difference of two VFDs between the treatment arms.

Efficacy analyses were performed in the intent-to-treat set, which included all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug and at least one efficacy assessment, assigned as randomized. Safety analyses were performed using the safety set, which comprised all patients who received at least one dose of study drug according to medication received, regardless of randomization.

Exploratory post hoc analyses were performed to identify patient subsets that may benefit most from trimodulin treatment. Subsets with a high mortality delta (defined as the difference between the percentage of patients who received trimodulin and died, and the percentage of patients who received placebo and died) were considered for further analyses (if the subsets were of sufficient size). Markers were selected taking into account the possible targeting of the inflammatory response or immunomodulatory capacity of trimodulin [23]. C-reactive protein (CRP) and IgM cutoff values were chosen to identify maximal differences between the trimodulin and placebo groups (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). Four subsets were identified for use in the post hoc analyses: patients with baseline levels of ≥ 70 mg/L CRP (high CRP), ≤ 0.8 g/L IgM (low IgM), CRP ≥ 70 mg/L and ≤ 0.8 g/L IgM (combined high CRP/low IgM), and ≥ 2 ng/mL procalcitonin (high procalcitonin [PCT]). For statistical methods and sample size calculation, refer to the Supplementary Methods.

Results

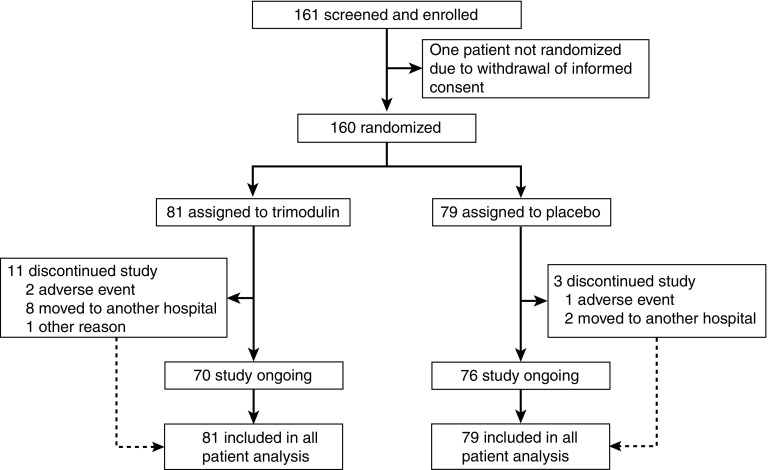

A total of 161 eligible patients were enrolled (from 24/41 sites [Germany, 10; Spain, 10; and UK, 4]) between October 4, 2011 and February 25, 2015; 160 patients were randomized (81 trimodulin; 79 placebo) and received at least one dose of study medication in addition to antibiotic treatment. Patient disposition is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition and reasons for discontinuation during the study period

No significant differences in patient demographics and other baseline characteristics (Table 1) were identified between the treatment groups except for higher PCT levels and higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II values in the placebo group. These higher levels of PCT at baseline were partially due to outliers (median 8.7, interquartile range [IQR] 1.9–30.6 ng/mL). Common comorbidities included hypertension, cardiac disorders, renal/urinary disorders, and nervous system disorders in both groups.

Table 1.

Demographics and other baseline characteristics in all patients

| Characteristic | Trimodulin (n = 81) | Placebo (n = 79) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | 0.675 | ||

| Male | 56 (69.1) | 57 (72.2) | |

| Female | 25 (30.9) | 22 (27.8) |

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.7 (14.5) | 66 (53–75) | 65.5 (14.8) | 67 (57–77) | 0.435 |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 26.5 (5.0) | 25.7 (23.3–29.6) | 25.9 (4.7) | 25.5 (23.1–28.0) | 0.410 |

| APACHE IIb | 23.1 (8.1) | 23 (18–29) | 26.2 (8.3) | 25 (20–33) | 0.036 |

| SOFA | 9.7 (3.8) | 11 (7–12) | 10.8 (3.5) | 11 (8–14) | 0.071 |

| CURB-65c | 2.7 (1.1) | 3 (2–4) | 2.8 (1.3) | 3 (2–4) | 0.637 |

| PaO2/FiOd2 | 134.7 (72.5) | 110.0 (82.0–173.6) | 133.7 (72.5) | 106.5 (77.0–185.7) | 0.937 |

| IgM (g/L) | 0.8 (0.79) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.7 (0.41) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.186 |

| IgG (g/L) | 6.8 (2.73) | 6.7 (5.0–8.9) | 6.6 (3.04) | 6.4 (4.2–8.2) | 0.530 |

| IgA (g/L) | 2.3 (1.14) | 2.1 (1.4–3.1) | 2.5 (1.78) | 2.0 (1.3–3.2) | 0.322 |

| CRP (mg/L)e | 220 (130.8) | 217 (121.5–325.3) | 227 (147.5) | 235 (88.2–333.5) | 0.723 |

| PCT (ng/mL)f | 8.3 (12.9) | 2.3 (0.7–10.4) | 23.3 (31.75) | 8.7 (1.9–30.6) | 0.0004 |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||||

| Cardiac disordersg | 39 (48.1) | 41 (51.9) | 0.752 | ||

| Hypertensionh | 42 (51.9) | 42 (53.2) | 0.876 | ||

| Diabetes mellitush | 15 (18.5) | 6 (7.6) | 0.060 | ||

| Nervous system disordersg | 21 (25.9) | 22 (27.8) | 0.859 | ||

| Neoplasm (benign, malignant, and unspecified)g | 22 (27.2) | 17 (21.5) | 0.463 | ||

| Renal and urinary disordersg | 41 (50.6) | 40 (50.6) | 1.000 | ||

| Sepsish | 13 (16.0) | 10 (12.7) | 0.654 | ||

| Septic shockh | 35 (43.2) | 44 (55.7) | 0.154 | ||

| Hepatic cirrhosish | 5 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.059 | ||

| Medication at baseline, n (%) | |||||

| Corticosteroids for systemic use | 24 (29.6) | 21 (26.6) | 0.375 | ||

| Antivirals for systemic use | 11 (13.6) | 12 (15.2) | 0.824 | ||

Data not available for a8 patients; b2 patients; c5 patients; d11 patients; eBaseline data substituted by day 1 data in 5 patients because of missing values. Data not available for 4 patients; fBaseline data substituted by day 1 data in 10 patients because of missing values. Data not available for 15 patients; gSystem Organ Class; hPreferred Term

Data are n (%), mean (SD), or median (IQR, 25th–75th percentile)

APACHE II Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; BMI body mass index; CRP C-reactive protein; CURB-65 Confusion, elevated blood Urea nitrogen, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, 65 years of age and older; IgM, IgG, IgA immunoglobulin M, G, and A; IQR interquartile range; PaO2/FiO2 ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen; PCT procalcitonin; SD standard deviation; SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score

*p values were calculated post hoc by Chi-square test for sex, two-sided t test for age, BMI, PaO2/FiO2, IgM/A/G, CRP, and PCT; by two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test for APACHE II, SOFA, and CURB-65; or by Fisher exact test for all medical history outcomes and concomitant medication

About 50% of patients had positive diagnosis by means of microbiological testing (Supplementary Table S1). The most frequent pathogens identified in both groups were species of Streptococci and Staphylococci, and approximately 20% of patients were diagnosed with viral pneumonia.

Antibiotic treatment and use of systemic corticosteroids were comparable between the treatment groups (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The majority of patients were treated according to the recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of CAP in adults and received antibiotic combination therapy (β-lactams + macrolides or β-lactams + fluoroquinolones). No significant differences in time to ICU admission were identified between treatment groups or study centers (data not shown).

Overall, the difference in the mean number of VFDs (primary endpoint) between the trimodulin and placebo groups was 1.4 days in favor of trimodulin, which was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of primary and secondary efficacy endpoints in trimodulin and placebo treatment groups in all patients

| Endpoint | Trimodulin | Placebo | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ||

| VFDs | n = 81 | n = 79 | |||

| 11.0 (9.5) | 11.0 (0–20) | 9.6 (9.4) | 8.0 (0–19) | 0.173 * | |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (days)a | n = 81 | n = 79 | |||

| 12.8 (8.5) | 10.0 (6–19) | 13.8 (8.6) | 11.0 (7–21) | Not calculated | |

| VFDs in surviving patients | n = 63 | n = 57 | |||

| 14.2 (8.4) | 18.0 (8–21) | 13.3 (8.5) | 16.0 (4–20) | 0.271† | |

| Vasopressor-free days | n = 81 | n = 79 | |||

| 13.0 (8.9) | 14.0 (6–20) | 13.7 (8.4) | 15.0 (8–20) | 0.639† | |

| Discharge time from ICU (days) | n = 81b | n = 79b | |||

| 13.4 (5.9) | 11.0 (9–17) | 14.4 (5.8) | 13.0 (10–18) | 0.161† | |

| Discharge time from hospital (days) | n = 81 | n = 79 | |||

| 19.5 (5.5) | 20.0 (15–24) | 19.0 (4.9) | 19.0 (15–23) | 0.479 | |

| 28-day all-cause mortality, n (%) | 18/81 (22.2) | 22/79 (27.8) | 0.465‡ | ||

| 28-day pneumonia-related mortality, n (%) | 5/81 (6.2) | 10/79 (12.7) | Not calculated | ||

| Change in SOFA score from day 1 to 7 | −4.8 (7.5) | −7.0 (−10–0) | −5.4 (6.5) | −7.0 (−10 to 3.0) | Not calculated |

aMortality is not considered for duration of mechanical ventilation; b34 patients were missing in the trimodulin group and 38 in the placebo group

ICU intensive care unit, IQR interquartile range, SD standard deviation, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, VFD ventilator-free day

Data are n (%), mean (SD) and median (IQR, 25th–75th percentile)

*One-sided Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test; †Wilcoxon test; ‡Mantel–Haenszel test

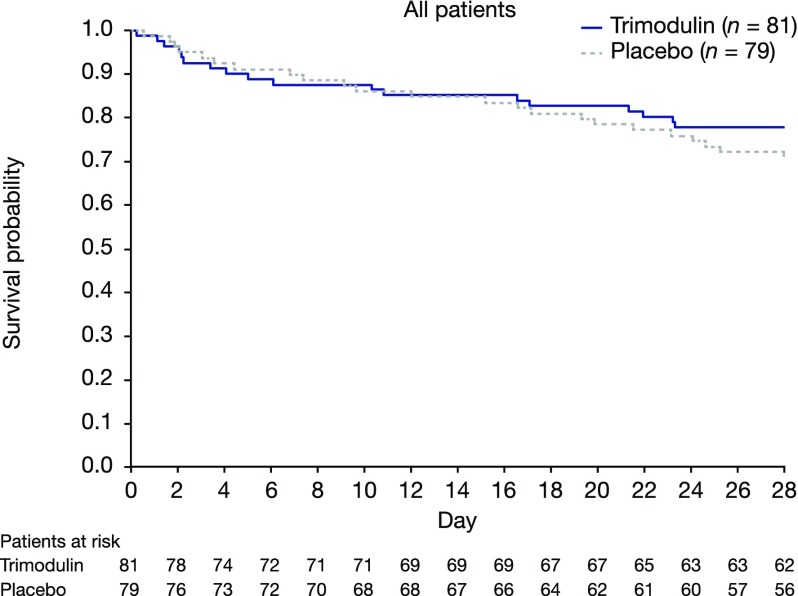

There was an absolute reduction in 28-day all-cause mortality of 5.6% (Table 2 and Fig. 2) and a relative reduction in mortality of 20.1% in the trimodulin group versus placebo. For pneumonia-related mortality, the absolute reduction was 6.5% (Table 2) and the relative reduction was 51.2%. Time to discharge from ICU to the ward, mean duration of hospitalization, and vasopressor-free days were not significantly different (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Survival by treatment regimen

TEAE incidences (including serious AEs [SAEs]), overall and throughout the majority of System Organ Classes (SOCs), were comparable between the trimodulin and placebo groups. Differences considered relevant for the trimodulin group were observed in the SOCs “renal and urinary disorders” and “hepatobiliary disorders”; these mainly resulted from “acute renal failure” (reported in 17 [21%] individuals in the trimodulin group and 8 [10.1%] in the placebo group) and “cholestasis” (reported by 8 [9.9%] and 2 [2.5%] individuals in the trimodulin and placebo groups, respectively). There were significantly more TEAEs in the SOC “infections and infestations” reported in the placebo group (p = 0.004; Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs; safety analysis set)

| Trimodulin (n = 81) | Placebo (n = 79) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall incidence | 75 (92.6) | 75 (94.9) | 0.746 |

| TEAEs with onset during infusion and up to 24 h after infusion end | 67 (82.7) | 67 (84.8) | 0.831 |

| Serious TEAEs | 62 (76.5) | 62 (78.5) | 0.850 |

| TEAEs with fatal outcomea | 20 (24.7) | 23 (29.1) | 0.594 |

| Discontinuation due to TEAEs | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.3) | 1.000 |

| TEAEs by System Organ Class (≥ 5% of patients) | |||

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 33 (40.7) | 34 (43.0) | 0.873 |

| Cardiac disorders | 31 (38.3) | 27 (34.2) | 0.624 |

| Vascular disorders | 30 (37.0) | 30 (38.0) | 1.000 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 29 (35.8) | 29 (36.7) | 1.000 |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 29 (35.8) | 40 (50.6) | 0.079 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 27 (33.3) | 36 (45.6) | 0.145 |

| Infections and infestations | 27 (33.3) | 45 (57.0) | 0.004 |

| General disorders and administration-site conditions | 22 (27.2) | 31 (39.2) | 0.131 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 20 (24.7) | 12 (15.2) | 0.167 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 18 (22.2) | 23 (29.1) | 0.367 |

| Investigations | 15 (18.5) | 13 (16.5) | 0.836 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 14 (17.3) | 14 (17.7) | 1.000 |

| Nervous system disordersb | 13 (16.0) | 8 (10.1) | 0.350 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 12 (14.8) | 4 (5.1) | 0.063 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 9 (11.1) | 11 (13.9) | 0.639 |

| Injury, poisoning, and connective tissue disorders | 8 (9.9) | 8 (10.1) | 1.000 |

Data are n (%)

There were no adverse drug reactions leading to death in either treatment group

aSafety set includes patients with TEAE onset before day 28, but who died due to TEAE after day 28

bAll events were reported for single patients only, except for critical illness polyneuropathy and vocal cord paralysis, each reported for 2 (2.5%) patients in the trimodulin group, and headache, which was reported for 3 (3.7%) patients in the trimodulin group

*p values were calculated post hoc by Fisher exact test

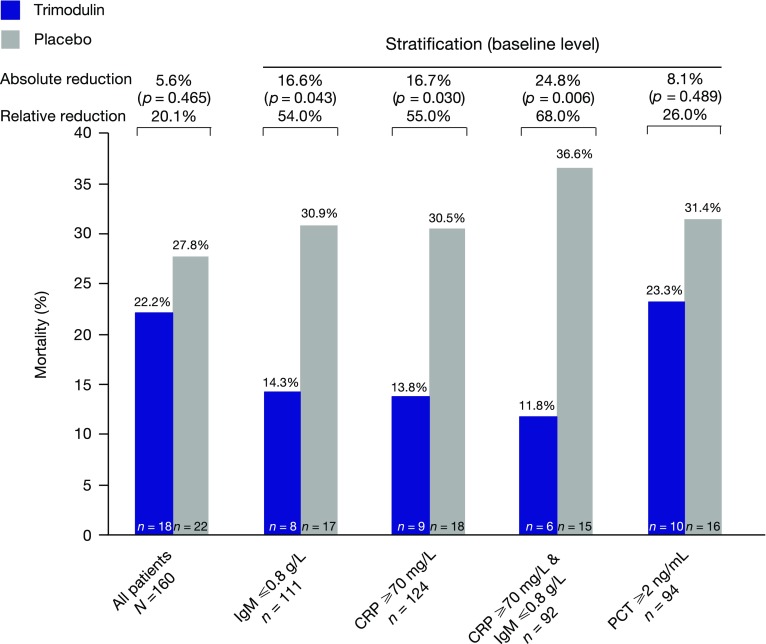

Exploratory post hoc analyses were performed to identify patient subsets that may benefit most from trimodulin treatment (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). Cutoff values were set to values with maximum mortality difference between the treatment groups. Only groups representing the majority of the study population are reported here. The post hoc subsets presented included 124 (77.5%) patients with baseline levels of high CRP, 111 (69.4%) patients with low IgM, 92 (57.5%) patients with combined high CRP and low IgM, and 94 (58.8%) patients with high PCT.

In general, no significant differences in patient demographics and other baseline characteristics were identified between the patient subsets of the treatment groups (Supplementary Tables S4–7) with the following exceptions: lower SOFA scores and PCT values in the trimodulin group (CRP and PCT subsets), lower APACHE II scores and PCT levels in the trimodulin group (IgM subset), and lower levels of PCT in the trimodulin group (CRP/IgM subset). Adjustment for the difference in PCT values was performed by exclusion of PCT outliers. The remaining patients had comparable PCT values and still showed substantial mortality difference between the treatment arms. In summary, the difference in PCT values does not explain the observed mortality difference in the subsets.

The differences in mean VFDs for trimodulin versus placebo were 2.9, 3.5, 3.9, and 3.4 days in the high CRP, low IgM, combined high CRP/low IgM, and high PCT subsets, respectively (Table 4). Importantly, 28-day all-cause mortality was substantially reduced in the trimodulin group versus placebo in each subset (absolute reductions of 16.7%, 16.6%, 24.8%, and 8.1%, respectively), with a reduction in absolute mortality of up to 24.8% (p = 0.006) in the combined high CRP/low IgM subset (68.0% relative reduction; Fig. 3). Kaplan–Meier analyses for the high CRP, low IgM, and combined subsets are presented in Supplementary Figs. S3–5. Data on 28-day all-cause mortality for all patient groups analyzed, including those that did not represent the majority of the study population, are reported in Supplementary Table S8.

Table 4.

VFDs in trimodulin and placebo groups in patient subsets

| Patient subset | Trimodulin | Placebo | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| VFD mean (95% CI) | VFD mean (95% CI) | ||

| CRP ≥ 70 mg/L | n = 65 | n = 59 | |

| 12.1 (9.8–14.4) | 9.2 (6.8–11.6) | 0.044 | |

| IgM ≤ 0.8 g/L | n = 56 | n = 55 | |

| 12.4 (10.0–14.9) | 8.9 (6.5–11.4) | 0.031 | |

| CRP ≥ 70 mg/L and IgM ≤ 0.8 g/L | n = 51 | n = 41 | |

| 12.6 (10.1–15.2) | 8.7 (5.8–11.6) | 0.031 | |

| PCT ≥ 2 ng/mL | n = 43 | n = 51 | |

| 11.2 (8.2–14.1) | 7.8 (5.2–10.3) | 0.047 |

Data are mean ± 95% confidence interval (CI)

CRP, IgM, and PCT were measured at baseline

CI confidence interval, CRP C-reactive protein, IgM immunoglobulin M, PCT procalcitonin, VFD ventilator-free day

*One-sided p values based on Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction (0.5); significance level 0.025

Fig. 3.

Twenty-eight-day all-cause mortality in trimodulin and placebo treatment groups in all patients and in patient subsets. Mortality was assessed in all patients and in stratified patient populations based on baseline levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 70 mg/L, immunoglobulin (Ig) M ≤ 0.8 g/L, or both criteria combined, or procalcitonin (PCT) ≥ 2.0 ng/mL. Actual numbers of deaths are given at the bottom of each column

Discussion

The CIGMA study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a novel therapeutic polyclonal antibody preparation, trimodulin, in severely ill patients with sCAP.

Although the difference observed in the primary endpoint of VFDs, with a mean increase of 1.4 days and median increase of 3 days in favor of trimodulin, was not significant, this difference may be considered clinically relevant. According to the clinical study protocol, the study was powered to detect a mean difference of 2 days between treatment groups. Further, although the study was not powered for mortality, and the reductions in 28-day all-cause and pneumonia-related mortality were not significant with add-on trimodulin compared with placebo, the relative reductions of 20% in all-cause mortality and 51% in pneumonia-related mortality in trimodulin-treated patients warrant further investigation.

In the CIGMA study, IgM levels were low in the majority of patients compared with the normal range. IgM levels range from 0.4 to 2.5 g/L [24]. Historical data suggest that low IgA and IgG levels are associated with a greater risk of mortality in CAP [25], and that low IgM concentrations in patients with sepsis or viral infections are related to a negative outcome [11, 12, 26].

Moreover, high CRP and PCT levels may be prognostic of poor outcomes in CAP [27, 28]. In our subgroup analysis, the cutoffs for levels of CRP (≥ 70 mg/L) and PCT (> 2 ng/mL) are comparable to historically published values, and high levels of each may generally be considered to indicate systemic and severe infections [29, 30]. Torres et al. showed that methylprednisolone reduced treatment failure compared with placebo in 120 patients with sCAP and a high systemic inflammatory response (CRP > 150 mg/L); in-hospital mortality, however, was similar [9].

In the post hoc analyses of the CIGMA study reported here, absolute mortality reduction was 16.7% for the high CRP subset, 16.6% for the low IgM subset, and 24.8% for the combined high CRP/low IgM subset; the relative reduction in mortality was 54–68% in favor of trimodulin.

The definition of pneumonia-related death or comorbidity was challenging in this complex patient population and required a subjective assessment of each case by the investigator. Further, comorbidities at study entry may particularly influence outcome in elderly patients—the relatively high all-cause mortality in trimodulin-treated patients > 65 years of age compared with patients 40–65 years of age may be associated with comorbidities rather than with an underlying infection (data not shown). Indeed, many patients who died did not have elevated CRP (data not shown). Generally, diagnosis of CAP is complex and may result in misdiagnosis, and inflammation parameters, such as CRP, have been investigated to support diagnosis [31]. In a future clinical trial with trimodulin in sCAP, CRP could help to support the diagnosis and differentiate sCAP from other conditions (by excluding patients with similar symptoms who have other underlying diseases), thereby enrolling a more targeted study population.

In the present study, incidences of TEAEs (including SAEs) were comparable between both treatment groups. Most patients had multiple comorbidities. SOCs with TEAEs reported more frequently in the trimodulin group were “renal and urinary disorders” and “hepatobiliary disorders” mainly resulting from patients experiencing “acute renal failure” (21% patients in the trimodulin group vs. 10.1% in the placebo group) and non-serious “cholestasis” (9.9% vs. 2.5%, respectively). Acute renal failure is a common comorbidity in sCAP [3], and is an established potential risk during conventional intravenous IgG treatment [32]. All cases of acute renal failure in the current study occurred in patients with pre-existing renal impairment and in patients at high risk for renal failure. Notably, the incidence of renal TEAEs in the trimodulin group (21%) was lower than would be expected in patients with sCAP, in whom the incidence of acute kidney injury has been reported to be up to 38% (10/26) [33].

Confounding factors were identified in all patients with cholestasis, including parallel intake/infusion of multiple drugs with possible effects on the liver, and/or confounding medical history. All adverse drug reactions of cholestasis were reported from one study center, so the possibility of a treatment interaction with concomitant medication should be considered.

Targeting the immune response with novel therapies such as trimodulin may provide additional protection against secondary infections and reduce mortality due to infection-related TEAEs such as sepsis. In this study, the incidence of TEAEs of all types of infection was significantly lower with trimodulin add-on treatment than with placebo, suggesting an additional protective effect against infection.

All of the above TEAEs are considered to be controllable under ICU conditions and close monitoring. Despite the failed primary endpoint, but given the trend in reduction of mortality further solidified by post hoc analyses, the risk profile of trimodulin is considered favorable for further clinical investigations.

Limitations of this study were that biomarkers and cutoff values used in the post hoc analyses were not prespecified in the study protocol. In addition, for the stratification of the patients into subsets, only baseline PCT values were used: data from serial measurements were not considered. There was a significant difference in baseline PCT values, with higher mean values in the placebo group. Further statistical tests were performed to adjust for this difference (data not shown). However, the difference in baseline PCT values does not explain the observed mortality differences between the treatment arms in the patient subsets. In future clinical trials with trimodulin, serial PCT measurements will be considered, as lack of reduction in PCT levels may better predict treatment failure and mortality than absolute values. Additionally, differences in severity of illness (APACHE II and SOFA score) were observed in this study in favor of the control group. However, these differences were not significant in the high CRP/low IgM subset, which showed the highest survival benefit for trimodulin. Finally, although patients received antibiotics on the day of randomization, the exact time point of treatment initiation was not recorded.

Conclusions

The phase II CIGMA study reported here did not meet the primary endpoint of VFDs following add-on treatment with trimodulin in severely ill patients with sCAP. However, post hoc analyses of patient subsets with high CRP, low IgM, and combined high CRP/low IgM baseline levels could be used to inform further investigation of trimodulin in a large, global phase III study that is powered for mortality in a targeted patient population with sCAP.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Professional medical writing assistance was provided by Fiona Boswell, PhD, and editorial assistance was provided by Katie Lay, MSc, at Caudex (Oxford, UK), funded by Biotest AG. Accovion GmbH, Eschborn, Germany (now Clinipace Worldwide, Morrisville, North Carolina, USA) provided study management services. We would like to thank all centers and staff involved in this study, and the patients and their families. Bernd H. Belohradsky, V. Marco Ranieri (Chair), Richard Strauss, and Gerhard W. Sybrecht monitored patient safety and data integrity as members of the DSMB.

Author Contributions

All authors critically reviewed drafts of the manuscript, had final approval of the version to be published, attest to the accuracy and integrity of the data, and agree to be accountable for all respective aspects of the work. TW contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. RPD contributed to study conception and design, and data analysis and interpretation. HE contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. MF contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, and data analysis and interpretation. SMO contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, attests to the accuracy of the study report, and agrees to be accountable for its contents. MS contributed to data analysis and interpretation. J-LV contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. KW contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, and data analysis and interpretation. IM-L contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. JA contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. AA contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. JIA contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. SN contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. RF contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. GSR contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. MS-H contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. FA-L contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. RR contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. J-MS contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. SK contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. KZ contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. JBM contributed to patient recruitment and acquisition of data. HL contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. GW contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. UA contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, and acquisition of data. DB contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. AK contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. MSG contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. JB contributed to patient recruitment and acquisition of data. MK contributed to patient recruitment and data analysis and interpretation. HPR contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. MPW contributed to patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. BHB contributed to data analysis and interpretation. IB contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, and acquisition of data. BD contributed to data analysis and interpretation. PD contributed to data analysis and interpretation. PL contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. MM contributed to acquisition of data and data analysis and interpretation. JS contributed to data analysis and interpretation. AW-D contributed to study conception and design, and data analysis and interpretation. UW contributed to study conception and design, and data analysis and interpretation. DW contributed to study conception and design, and data analysis and interpretation. AT contributed to study conception and design, patient recruitment, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Biotest AG, Dreieich, Germany. Biotest employees and contract research organization subcontractors were involved in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and writing of this manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interests

TW has served on advisory boards, received funding for institutional research, and honoraria from Biotest AG. RPD has received personal fees from Biotest AG for serving on the advisory board for this trial, institutional funding from Spectral Diagnostics, and personal fees for consulting from Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Spectral. HE has served on advisory boards for Biotest AG and received honoraria from Biotest AG. MF has served on advisory boards for Biotest AG. SMO has served on advisory boards for Aridis and Arsanis, and received institutional funding from Asahi Kasei and Ferring, and consultancy fees from Biotest AG. MS has received honoraria from Biotest AG for participation in advisory boards and satellite symposia. KW is a member of the Biotest BT086 Advisory Board and has received honoraria, research funding, consulting fees, and funding for travel from Biotest AG. IM-L has served on advisory boards for Biotest AG. AA has received institutional research funding and honoraria from GRIFOLS Co, and consulting fees from Asahi Kasei. RF has received honoraria from MSD, Pfizer, and Toray. MS-H has received travel costs for speaking at a Biotest seminar. FA-L has served on advisory boards for Gilead and MSD. SK has served on advisory boards for ANOMED, Astellas, Baxter, Fresenius, Gambro, Gilead, MSD, NovaLung, Novartis, and Pfizer; has received institutional research funding from NovaLung and Pfizer, and honoraria from ArjoHuntleigh, Astellas, Basilea, Baxter, Biotest AG, CSL Behring, Cytosorbents, Fresenius, Gilead, MSD, NovaLung, Pfizer, Orion, Sedana, Sorin, and Thermo Fisher Scientific. KZ has received research grants, honoraria, and financial support (education) for his department from Abbott, AbbVie Deutschland KG, Aesculap Akademie, AIT GmbH, Amomed GmbH, art tempi GmbH, Ashai Kasai Pharma, Astellas Pharma, B. Braun Avitum AG, B. Braun Melsungen AG, Bayer AG, Biotest AG, Codan PVB Medical, Covidien GmbH, CSL Behring, Delab GmbH, Dr. F. Köhler Chemie, Dr Rothenberger, Dräger Medical, ECCPS, Edward Life Science GmbH, Enterprise Analyses, Envico SRL, European Union, Ferring Arzneimittel, Forum Sanitas, Fresenius Kabi, Fresenius Medical Care, German Research Federation Gilead, Haemonetics Corporation, Hamilton Medical AG, Heinen + Löwenstein, Hepanet GmbH, Hexal AG, High Tech Grundungsford, INC Research, Josef Gassner, Karl Storz AG, Kentours Producciones, LOEWE TP 6, M&M Gesundheitsnetzwerk, Maquet GmbH, Marien-Akademie, Markus Lucke Kongress Organisation, Masimo, Massimo International, med-Update GmbH, Medtronic GmbH, MSD Sharp & Dohme, Mundipharma GmbH, Nordic Group, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Novo Nordisk Pharma GmbH, Orion Pharma GmbH, Pall GmbH, Pfizer, Photonics GmbH, Pulsion Medical Systems S.E., Radiometer GmbH, Ratiopharm GmbH, Reha Medi GmbH, Salvia Medical GmbH, Sarstedt GmbH, Schochl Medical Research Österreich, Serumwerke Berneburg, Siemens Healthcare, Smith Medical GmbH, Sorin Group, Sysmex, Teflex Medical GmbH, TEM International, Teva GmbH, Thieme Verlag, Verathon Medical, and Vifor Pharma. UA has received reimbursement for educational support and travel costs from Biotest AG. DB has received funding for institutional research at the trial site only. MK has served on advisory boards for MSD and Pfizer, and has received honoraria from Astellas, Gilead, MSD, and Pfizer. AT has served on advisory boards for Aridis, Bayer, GSK, Pfizer, Polyphor, and Roche. J-LV, JA, JIA, SN, GSR, RR, J-MS, JBM, HL, GW, AK, MSG, JB, HPR, MPW, and BHB have no interests to declare. IB, BD, PD, PL, MM, JS, AW-D, UW, and DW are employees of Biotest AG. UW, JS, and AW-D also hold stocks/shares in Biotest AG.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00134-018-5143-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Torres A, Peetermans WE, Viegi G, Blasi F. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults in Europe: a literature review. Thorax. 2013;68:1057–1065. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, Fakhran S, Balk R, Bramley AM, Reed C, Grijalva CG, Anderson EJ, Courtney DM, Chappell JD, Qi C, Hart EM, Carroll F, Trabue C, Donnelly HK, Williams DJ, Zhu Y, Arnold SR, Ampofo K, Waterer GW, Levine M, Lindstrom S, Winchell JM, Katz JM, Erdman D, Schneider E, Hicks LA, McCullers JA, Pavia AT, Edwards KM, Finelli L. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415–427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodhead M, Welch CA, Harrison DA, Bellingan G, Ayres JG. Community-acquired pneumonia on the intensive care unit: secondary analysis of 17,869 cases in the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Crit Care. 2006;10(Suppl 2):S1. doi: 10.1186/cc4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kellum JA, Kong L, Fink MP, Weissfeld LA, Yealy DM, Pinsky MR, Fine J, Krichevsky A, Delude RL, Angus DC. Understanding the inflammatory cytokine response in pneumonia and sepsis: results of the Genetic and Inflammatory Markers of Sepsis (GenIMS) study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1655–1663. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calfee CS, Delucchi K, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Ware LB, Matthay MA. Subphenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome: latent class analysis of data from two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:611–620. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70097-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alejandria MM, Lansang MA, Dans LF, Mantaring JB., III Intravenous immunoglobulin for treating sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001090.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreymann KG, de Heer G, Nierhaus A, Kluge S. Use of polyclonal immunoglobulins as adjunctive therapy for sepsis or septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2677–2685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibila O, Rodrigo-Troyano A, Torres A. Nonantibiotic adjunctive therapies for community-acquired pneumonia (corticosteroids and beyond): where are we with them? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;37:913–922. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torres A, Sibila O, Ferrer M, Polverino E, Menendez R, Mensa J, Gabarrus A, Sellares J, Restrepo MI, Anzueto A, Niederman MS, Agusti C. Effect of corticosteroids on treatment failure among hospitalized patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia and high inflammatory response: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Torre MC, Toran P, Serra-Prat M, Palomera E, Guell E, Vendrell E, Yebenes JC, Torres A, Almirall J. Serum levels of immunoglobulins and severity of community-acquired pneumonia. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2016;3:e000152. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2016-000152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Apostolidou E, Lada M, Perdios I, Gatselis NK, Tsangaris I, Georgitsi M, Bristianou M, Kanni T, Sereti K, Kyprianou MA, Kotanidou A, Armaganidis A. Kinetics of circulating immunoglobulin M in sepsis: relationship with final outcome. Crit Care. 2013;17:R247. doi: 10.1186/cc13073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Justel M, Socias L, Almansa R, Ramirez P, Gallegos MC, Fernandez V, Gordon M, Andaluz-Ojeda D, Nogales L, Rojo S, Valles J, Estella A, Loza A, Leon C, Lopez-Mestanza C, Blanco J, Berezo JA, Rosich S, Cilloniz C, Torres A, de Lejarazu RO, Martin-Loeches I, Bermejo-Martin JF. IgM levels in plasma predict outcome in severe pandemic influenza. J Clin Virol. 2013;58:564–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehrenstein MR, Notley CA. The importance of natural IgM: scavenger, protector and regulator. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:778–786. doi: 10.1038/nri2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esen F, Tugrul S. IgM-enriched immunoglobulins in sepsis. In: Vincent JL, editor. Yearbook of intensive care and emergency medicine. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rieben R, Roos A, Muizert Y, Tinguely C, Gerritsen AF, Daha MR. Immunoglobulin M-enriched human intravenous immunoglobulin prevents complement activation in vitro and in vivo in a rat model of acute inflammation. Blood. 1999;93:942–951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duerr C, De Martin A, Sachet M, Konrad T, Baumann S, Spittler A. Influence of an immunoglobulin-enriched (IgG, IgA, IgM) solution on activation and immunomodulatory functions of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in a LPS second-hit model. Crit Care. 2011;15(Suppl 1):P244. doi: 10.1186/cc9664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shmygalev S, Damm M, Knels L, Strassburg A, Wunsche K, Dumke R, Stehr SN, Koch T, Heller AR. IgM-enriched solution BT086 improves host defense capacity and energy store preservation in a rabbit model of endotoxemia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016;60:502–512. doi: 10.1111/aas.12652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welte T, Dellinger RP, Ebelt H, Ferrer M, Opal SM, Schliephake DE, Wartenberg-Demand A, Werdan K, Loffler K, Torres A. Concept for a study design in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia: a randomised controlled trial with a novel IGM-enriched immunoglobulin preparation—the CIGMA study. Respir Med. 2015;109:758–767. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welte T, Almirall J, Ayesteran JI, Artigas A, Nuding S, Rodriguez G, Ferrer R, Shankar-Hari M, Alvarez Lerma F, Riessen R, Sirvent J-M, Kluge S, Lapp H, Wobker G, Zacharowksi K, Bonastre Mora J, Wartenburg-Demand A, Langohr P, Daelken B, Torres A (2018) Reduction in mortality with a novel polyclonal antibody preparation in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. https://www.escmid.org/escmid_publications/escmid_elibrary/?q=welte&id=2173&L=0&tx_solr%5Bsort%5D=relevance%2Basc&tx_solr%5Bfilter%5D%5B0%5D=main_filter_eccmid%253Atrue&tx_solr%5Bfilter%5D%5B1%5D=pub_date%253A201701010000-201712312359&x=0&y=0. Accessed 26 Jan 2018

- 20.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Jr, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–S72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoenfeld DA, Bernard GR. Statistical evaluation of ventilator-free days as an efficacy measure in clinical trials of treatments for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1772–1777. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF III, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J (2009) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150:604–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Becze Z, Molnar Z, Fazakas J. Can procalcitonin levels indicate the need for adjunctive therapies in sepsis? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(Suppl 1):S13–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (2017) Immunoglobulins. http://www.ouh.nhs.uk/immunology/diagnostic-tests/tests-catalogue/immunoglobulins.aspx. Accessed 22 Mar 2017

- 25.de la Torre MC, Bolibar I, Vendrell M, de Gracia J, Vendrell E, Rodrigo MJ, Boquet X, Torrebadella P, Yebenes JC, Serra-Prat M, Rello J, Torres A, Almirall J. Serum immunoglobulins in the infected and convalescent phases in community-acquired pneumonia. Respir Med. 2013;107:2038–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bermejo-Martin JF, Rodriguez-Fernandez A, Herran-Monge R, Andaluz-Ojeda D, Muriel-Bombin A, Merino P, Garcia-Garcia MM, Citores R, Gandia F, Almansa R, Blanco J. Immunoglobulins IgG1, IgM and IgA: a synergistic team influencing survival in sepsis. J Intern Med. 2014;276:404–412. doi: 10.1111/joim.12265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Hill AT. C-reactive protein is an independent predictor of severity in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2008;121:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bloos F, Marshall JC, Dellinger RP, Vincent JL, Gutierrez G, Rivers E, Balk RA, Laterre PF, Angus DC, Reinhart K, Brunkhorst FM. Multinational, observational study of procalcitonin in ICU patients with pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation: a multicenter observational study. Crit Care. 2011;15:R88. doi: 10.1186/cc10087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Povoa P, Coelho L, Almeida E, Fernandes A, Mealha R, Moreira P, Sabino H. C-reactive protein as a marker of infection in critically ill patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ugarte H, Silva E, Mercan D, De Mendonca A, Vincent JL. Procalcitonin used as a marker of infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:498–504. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199903000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Bel J, Hausfater P, Chenevier-Gobeaux C, Blanc FX, Benjoar M, Ficko C, Ray P, Choquet C, Duval X, Claessens YE. Diagnostic accuracy of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin in suspected community-acquired pneumonia adults visiting emergency department and having a systematic thoracic CT scan. Crit Care. 2015;19:366. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dantal J. Intravenous immunoglobulins: in-depth review of excipients and acute kidney injury risk. Am J Nephrol. 2013;38:275–284. doi: 10.1159/000354893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bacci MR, Leme RC, Zing NP, Murad N, Adami F, Hinnig PF, Feder D, Chagas AC, Fonseca FL. IL-6 and TNF-alpha serum levels are associated with early death in community-acquired pneumonia patients. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2015;48:427–432. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20144402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.