Abstract

Objectives

Nursing homes (NHs) collaboration with hospices appears to improve end-of-life (EOL) care among dying NH residents. However, the potential benefits of NH-hospice collaboration may vary with the patterns of this collaboration. This study examines the relationship between the attributes of NH-hospice collaboration, especially the exclusivity of NH-hospice collaboration (i.e. the number of hospice providers in a NH), and EOL hospitalizations among dying NH residents.

Design

This national retrospective cohort study linked 2000–2009 NH assessments (i.e. the Minimum Data Set 2.0) and Medicare data. A linear probability model with facility fixed-effects was estimated to examine the relationship between EOL hospitalization and the attributes of NH-hospice collaborations, adjusting for individual and facility characteristics. We also performed a set of sensitivity analyses, including stratified analyses by volume of hospice services in a NH and stratified analyses by rural versus urban NH locations.

Settings

All Medicare and/or Medicaid certified U.S. NHs with at least 8 years of data and at least 30 beds.

Participants

NH decedents resided in Medicare and/or Medicaid certified NHs in the U.S. between 2000 and 2009. We restricted the analyses to those continuously enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) in the last 6 month of life and those who were in NHs for the last 30 days of life. In total, we identified 2,954,276 NH decedents over the study period.

Measurement

The outcome variable was measured as dichotomous, indicating whether a dying NH residents was hospitalized in the last 30 days of life. The attributes of NH-hospice collaboration were measured by the volume of hospice services (defined as the ratio of number of hospice days to the total NH days per NH per calendar year) and the number of hospice providers in a NH (defined as the number of unique hospice providers in a NH per year). We categorized NHs into groups based on the number of hospice providers (1, 2 or 3, and ≥ 4) in the NH, and conducted sensitivity analysis using a different categorization (1, 2, and 3+ hospice providers).

Results

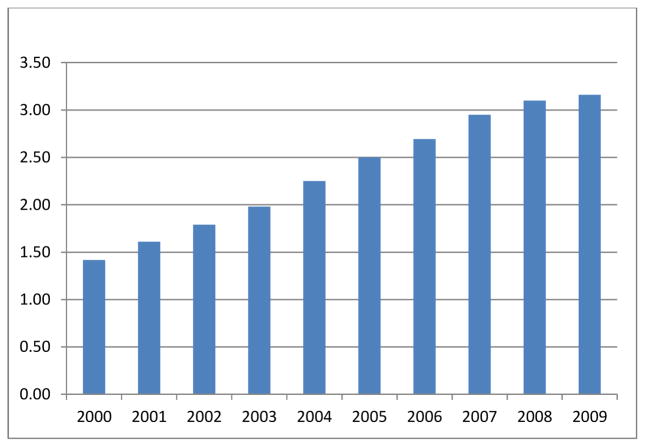

The pattern of NH-hospice collaboration changed significantly over years – the average number of hospices in a NH increased from 1.4 in 2000 to 3.2 in 2009. The volume of NH-hospice collaboration also increased substantially. The multivariate regression analyses indicated that having more hospice providers in the NH was not associated with lower risks of EOL hospitalizations. After accounting for individual and facility characteristics, increasing hospice providers from 1 to at least 4 was associated with an overall 1 percentage point increase in the likelihood of EOL hospitalizations among dying residents (P<0.01), and such relationship remained in NHs with moderate or high volume NHs in the stratified analyses. Stratified analysis by rural versus urban NHs suggested that the relationship between the number of hospice providers and EOL hospitalizations was mainly in urban NHs.

Conclusion

More hospice providers in the NH was not associated with lower EOL hospitalizations, especially among NHs with relatively high volume of hospice services.

INTRODUCTION

Nearly 25% of decedents in the United States spend the last chapter of their lives in nursing homes (NHs).1 Hospitalizations among NH residents are prevalent. 2–5 About 44% of non-hospice NH residents are hospitalized in the last 30 days of their life.3 Many of these hospitalizations are unnecessary and cause significant disruption in care and often result in poor outcomes and additional physical and psychological deterioration of frail NH populations, especially among dying residents.6–9 These hospitalizations are also costly and incur a high financial burden on Medicare. 10–12, 6,7

The use of hospice care (provided through NH-hospice collaborations) appears to reduce EOL hospitalizations for dying NH residents.3,4,13–15 The potential impact of NH-hospice use on NH’s EOL practice may be influenced by the attributes of their collaborations,16–19 which may vary by the volume of hospice use (i.e. the amount of hospice services provided in a NH) and the exclusivity of collaboration (i.e. the number of different hospice providers in a NH). Higher volumes of hospice use may have a “practice makes perfect” effect – more frequent exposure to hospice providers may help NHs to better integrate the palliative care philosophies and approaches to EOL care advocated and practiced by hospice.17 On the other hand, an exclusive collaboration (i.e. fewer different hospice providers) is likely to lead to a more successful NH-hospice relationship, with fewer care conflicts and greater rapport, and resulting in better care.16,20 The association between these two attributes of NH-hospice collaborations, especially the exclusive partnership, and NH hospitalization rates among dying residents has not been adequately studied.

The rapidly expanding hospice market provides us with a unique opportunity to study the association between changing attributes of NH-hospice collaborations and EOL hospitalizations in NHs.21,22 For example, the rate of hospice use among NH decedents increased from 14% to 33% between 1999 and 2006, which paralleled the growth in the number of hospices serving NHs (from 1,850 in 1999 to 2,768 in 2006).23 Furthermore, there have been great variations in growth rates of hospice providers across states, which allow us to explore the association between NH EOL care and different patterns of NH-hospice collaborations.23,24

The objective of this study is to examine the association between the attributes of NH-hospice collaborations, especially the exclusive partnership, and EOL hospitalization rates among dying NH residents. Understanding such relationship is necessary for policymakers to adequately evaluate the costs and benefits of hospice use and consider policy changes to the Medicare hospice benefit.

METHODS

Data set

Nationwide data, including the Minimum Data Set 2.0, Medicare claims (inpatient, SNF, hospice, home health and outpatient claims) and Online Survey, Certification and Reporting (OSCAR, now the Certification and Survey Provider Enhanced Reporting [CASPER] data), between Jan 2000 and Dec 2009 were linked. The MDS 2.0 data contains detailed information on individuals’ socio-demographic characteristics, their health conditions, and their preference of care. Medicare claims capture individuals’ health care utilization covered by Medicare, such as hospitalizations, among Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) enrollees. OSCAR data contains annual information on NH characteristics, and allowed us to capture factors that may change over time (e.g. staffing level).

Study cohort

We included all NH decedents who were in Medicare/Medicaid certified free-standing NHs in the US between 2000 and 2009. We required these residents to be in NHs for the last 30 days of their life, and to be continuously enrolled in Medicare FFS all 6 months before death. Furthermore, we focused the analyses on free-standing NHs with at least 8 years of data and at least 30 beds. In total, we identified 2,954,276 decedents in 14,294 NHs over the study period.

Variables

The outcome variable was end-of-life (EOL) hospitalization, defined as whether a dying resident experienced any hospitalization in the last 30 days of life. We constructed two variables to represent the attributes of NH-hospice collaborations: 1) the annual volume of hospice use in a particular NH, defined as a continuous variable that reflected the proportion of total hospice days (i.e., days on hospice for all hospice residents) to total NH days (i.e., days in NH for all NH residents) in a calendar year, and 2) the number of unique hospice providers that provided services in a NH in a year (which reflect the extent of the exclusivity NH-hospice collaborations). We considered a hospice provider as a “valid” provider if the provider provided at least 10 days of services in a single year or over years (which accounted for 90% of the hospice providers that provided any services in NHs). Based on the distribution of the number of different hospice providers in a NH in a particular year, we categorized NHs as having collaborations with no hospice providers, one hospice provider, 2 or 3 hospice providers, or 4 and more hospice providers. We also performed a sensitivity analysis by categorizing NHs into groups with 0, 1, 2 and 3+ hospice providers.

Person-level characteristics included individual hospice enrollment status, the presence of do-not-hospitalize or do-not-resuscitate orders, sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age, gender, race, education, marital status), physical functional status (i.e. activities of daily living [ADL]), cognitive functional status (i.e. cognitive performance scale [CPS]), co-morbidities (e.g. diabetes, CHF dementia), and the presence of a terminal prognosis. We also adjusted for the secular trend by including indicators for the year of death. Lastly, we accounted for facilities characterisics that may change over time, such as residents payer-mix (e.g. % of Medicaid and Medicare) and staffing (e.g. registered nurses hours per residents per day), based on the OSCAR data.

Statistical Analysis

We first examined the changes in the attributes of NH-hospice collaboration (i.e. volume and the exclusivity of collaboration) over years. We then examined the relationships between the changes in the attributes of NH-hospice collaborations and the likelihood of EOL hospitalizations by using multivariable regression analyses. The unit of analysis was individual NH decedent. Specifically, we fit a linear probability model with facility fixed-effects and robust standard errors. The model controlled for individual level characteristics, time changing facility effects and year indicators. We chose to use a linear probability model because of its computational efficiency, and its approximation to the logistic regression.25 The fixed-effects model provided estimates of changes in outcomes within NH facility as the facility changed its collaboration pattern with hospices over time. By using within facility estimates, we controlled for differences in outcomes due to differences in quality between NHs that were invariant over time, and thus allowed us to better isolate the association between NH-hospice collaborations and EOL hospitalization. 25

As the potential impact of the exclusivity of NH-hospice relationship may vary with the volume of hospice care in a NH, we performed a sensitivity analyses that stratified facilities by the volume of hospice use (based on the distribution of hospice volume in NHs across all years) and estimated separate regressions in each subgroup. Furthermore, we stratified the analyses by urban versus rural NHs (based on the county of a NH’s location) since the availability of hospice providers or hospitals as well as practice patterns could differ in urban versus rural settings. Lastly, we performed an additional set of sensitivity analyses to check the robustness of our findings, including 1) different categorization of the unique number of hospice providers as independent variables (i.e. 0,1, 2, and 3+ hospice providers), 2) relaxing the requirement for a “valid” hospice provider by including hospice providers that provided any services in a NH, 3) restricting the analyses to NHs with at least 100 days of hospice services (accounting for 80% of the observations).

RESULTS

There was a significant change in EOL hospitalizations over the sample years. The prevalence of EOL hospitalizations among dying NH residents increased from 24.8% in 2000 to 33.3% in 2009. Also, the pattern of NH-hospice collaboration changed substantially. Specifically, the average proportion of hospice days in NHs (i.e. the volume of hospice use) increased from 2.0% in 2000 to 4.7% in 2009 (Figure 1). Additionally, there was an increasing trend in the number of hospice providers in NHs over the years, with the average number of hospice providers per NH increasing from 1.42 in 2000 to 3.16 in 2009 (Figure 2). The number of hospice providers also varied between rural and urban NHs. For example, the average number of hospice providers increased from 0.89 in 2000 to 2.13 in 2009 among rural NHs, and increased from 1.66 to 3.62 during the same time period among urban NHs.

Figure 1.

The average volume of hospice use in NHs (proportion of hospice days to total NH days in a calendar year) between 2000 and 2009.

Figure 2.

The average number of unique hospice providers within NHs between 2000 and 2009.

The findings from the multivariable regression analysis (for the entire sample) are presented in Table 1. At the individual level, hospice enrollment was associated with a lower risk of EOL hospitalization – dying residents who enrolled on hospice care were 13.1 percentage points less likely to be hospitalized compared to those not enrolled in hospice care. Controlling for individual and other time-varying NH characteristics, the attributes of NH-hospice collaboration were associated with the risk of EOL hospitalization. Specifically, a higher volume of hospice services in a NH was associated with a lower risk of EOL hospitalizations – a one percentage point increase in the volume of hospice services was associated with 0.15 percentage point decrease in the likelihood of EOL hospitalization (P<0.001). However, having more hospice providers in a NH was not associated with a lower likelihood of hospitalizations. After accounting for individual characteristics and volume of hospice use, an increase from 1 to 4 or more hospice providers in the NH was associated with 1 percentage point increase in the likelihood of EOL hospitalizations (P<0.001). The relationship between the exclusivity of NH-hospice collaboration and EOL hospitalizations estimated from the sensitivity analyses relaxing the requirement for “valid” hospice providers were consistent with the main analysis but with a relatively smaller effect size (results not shown in the table) – for example, an increase from 1 to 4 or more hospice providers in the NH was associated with 0.8 percentage point increase in the likelihood of EOL hospitalizations (P<0.001). Findings from the sensitivity analyses with different cut-off points to categorize the exclusivity of NH-hospice collaboration or the analyses among NHs with at least 100 days of hospice services were also consistent with the main analyses (results not shown in the table).

Table 1.

Relationship between NH-hospice collaboration and EOL hospitalization: results from linear probability model with facility fixed-effects.

| Hospitalizations with 30 days of life | Overall (without stratification) | Stratified Analysis: by volume | Stratified analyses: by rural versus urban NHs + | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High volume >=3% | Medium volume: >0. 29% & <3% | Low volume: <=0. 29% | Urban | Rural | ||

| N of individuals: 2,954,276 (N of NH=14,294) | N of individuals: 1,207,493 (N of NH=10,431) | N of individuals: 1,195,274 (N of NH=12,148) | N of individuals: 551,509 (N of NH=7,824) | N of individuals: 2,165,213 (N of NH=9,814) | N of individuals: 788,024 (N of NH=4,475) | |

| Hospice provider: 0 | −0.006*** (0.002) | / | / | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.009*** (0.002) | −0.004 (0.002) |

| Hospice provider: 1 | Reference | |||||

| Hospice provider: 2 or 3 | 0.006*** (0.001) | 0.004* (0.002) | 0.006*** (0.002) | 0.002 (0.003) | 0.008*** (0.001) | 0.004* (0.002) |

| Hospice provider: >=4 | 0.010*** (0.002) | 0.008*** (0.002) | 0.009*** (0.003) | 0.015 (0.013) | 0.011*** (0.002) | 0.005 (0.004) |

| % hospice days (Volume, on 0–100 scale) | −0.001*** (0.000) | −0.002*** (0.000) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.021 (0.013) | −0.001*** (0.000) | −0.002*** (0.000) |

| Main individual level | ||||||

| Hospice enrollment status | −0.131*** (0.001) | −0.156*** (0.001) | −0.107*** (0.001) | −0.034*** (0.004) | −0.133*** (0.001) | −0.124*** (0.002) |

Numbers in the cell denote coefficients and related robust standard errors (in the parenthesis)

The total numbers of observation is slightly different from the main analysis due to the missing values for the rural versus urban variable.

denotes P<0.01,

denotes P<0.05,

denotes P<0.1

We also accounted for additional variables in the regression analyses. Individual level variables include: age at death, female, white, marital status, do-not-hospitalize /do-not-resuscitate order, education, diabetes, congestive heart failure, other heart condition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/asthma, dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, renal disease, hip facture, depression, infection, terminal disease, pressure ulcers, activities of daily living (ADL), number of medications, and cognitive performance scale(CPS). NH level variables include: percent of Medicaid residents in a facility, percent of Medicare residents in a facility, any physician extender in a facility, licensed practice nurse (LPN) hours per residents per day, certified nurse assistant (CNA) hours per residents per day, registered nursing (RN) hours per residents per day. Year indicators were also accounted for in the regression.

The analyses stratified by NH hospice volume revealed that this negative relationship between the number of providers and EOL hospitalization was primarily in NHs with relatively high volume of hospice services (i.e. hospice volume>0.29%), but not in NHs with very low hospice volume (i.e. hospice volume<=0.29%). It is likely that NHs with low volume of hospice services may have fewer hospice providers, and thus we were not able to detect any significant findings. The stratified analysis by NH location (rural versus urban) indicated that the relationship between the number of hospice providers and EOL hospitalizations was mainly in urban NHs. For example, increasing from 1 to 4 or more hospice providers in rural NHs did not appear to have a statistically significant effect on EOL hospitalization (P=0.215). Increasing from 1 to 2 or 3 hospice providers in rural NHs was associated with 0.4 percentage point increase in the likelihood of EOL hospitalizations, and the effect size was marginally significant (P=0.051). The less significant findings in rural NHs was probably due to the smaller number of hospice providers in rural NHs. For example, the average number of hospice providers was 1.54 in rural NHs (58.95% of the rural NHs had less than 2 hospice providers and only 6.75% of them had 4 or more hospice providers) versus 2.72 in urban NHs (33.82% of the urban NHs had less than 2 provides and 26.61% of them had 4 or more hospice providers) across years.

DISCUSSION

Using population-based longitudinal data for decedents in U.S. NHs, this study examined the association between the attributes of NH-hospice collaborations and EOL hospitalizations among dying NH residents. We found that attributes of NH-hospice collaborations were associated with the likelihood of EOL hospitalizations, accounting for resident hospice enrollment status, other individual characteristics and facility characteristics.

As expected, we found that a higher volume of hospice use in a NH was related to lower risks of EOL hospitalizations among dying NH residents. More frequent exposure to hospice services may help NHs to better integrate the palliative care philosophies and approaches to EOL care advocated and practiced by hospice,17 which may improve NHs’ overall capabilities to provide palliative care and to maintain residents in place, 16,26 and consequently reduce EOL hospitalizations. 16–18 More hospice exposure may also enhance the communication between NHs and hospices and mitigate potential conflicts between these two entities. However, while a higher volume of hospice collaboration may contribute to a “practice makes perfect” effect, having more unique hospice providers in a NH is not necessarily related to better EOL care for dying residents. In fact, this study found that having four or more providers was associated with higher EOL hospitalization rates. NHs are complex organizations with a care culture different from those of hospices. “Outside” hospice providers may disrupt a NH’s routines and challenge its care practices, resulting in conflicts and/or poor care coordination.16,18,27 A more exclusive collaboration with a hospice provider may enable NHs to develop a successful and long-term relationship and loyalty to a particular EOL care delivery approach, while minimizing the management time needed to address potential staff conflicts.16,18 Such relationship may also lead to fewer care conflicts and greater rapport, and resulting in better NH care in NHs.16,20 On the other hand, collaborating with multiple hospice providers may attenuate the benefits NHs gain from collaboration – the coordination and communication between NHs and hospice providers may suffer, and thus affect the quality of EOL care in NHs.

Improving EOL care and reducing unnecessary hospitalizations is a focus of health care delivery systems and relationships between hospices and NHs (resulting in NH resident hospice enrollment) appear to help reduce unnecessary hospitalizations. However, to achieve the ultimate benefit of a NH-hospice collaboration likely requires effective and efficient communication and coordination between the two entities. To ensure the quality of care provided to patients who receive hospice services in long-term care settings and to ensure the establishment of coordinated plan of care between them, the CMS issued regulations that emphasize the need for this close coordination, such as clear written agreements and plan of care, between hospice providers and the long-term care settings in 2013. 28 However, whether such regulation has effectively improved the care communication and coordination between hospice and NHs is unclear. Future research is warranted to explore potential interventions to promote effective and efficient hospice care and EOL care in NHs.

There are some limitations of the study. The main limitation of this study is that there could be unobserved concurrent changes (such as change in NH practice) to confound the relationship between hospice use and EOL hospitalizations even though we controlled for a detailed list of variables reflecting time varying facility characteristics and individual conditions over years. However, the growth of hospice providers in NH markets was likely to be associated with hospice provider incentives (i.e. higher potential profit margins, as indicated by a OIG report29), which were likely to be independent of other unobserved changes in NHs that could affect EOL hospitalizations. Second, it is worth noting that the relationship between the number of hospice providers and EOL hospitalizations may not be directly applied to rural NHs – due to the low numbers of hospice providers in rural NHs, our data did not have enough power to detect the relationship between the number of hospice providers and EOL hospitalizations in rural NHs. Thus it is unclear whether these rural facilities would behave differently with multiple hospice providers. Third, we did not directly observe whether a NH actually had an exclusive contractual relationship with a hospice provider. Rather we inferred such a relationship by observing the number of unique hospice providers used by a NH’s residents (using Medicare claims data). Lastly, we were unable to determine who initiated the hospice referral (e.g. NHs initiated versus others) due to the limitation of the administrative data. Further qualitative studies may be needed to understand these questions.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we examined the association between the attributes of NH-hospice collaborations and EOL hospitalization among dying residents. We found that having more hospice providers in a NH was not associated with better outcomes (i.e. lower risks of EOL hospitalizations), especially among NHs with a relatively high volume of hospice services. The findings from this study suggest that NHs should be encouraged to limit the number of hospice collaborations to a manageable number, and to balance providing choices to residents with the NH’s ability to manage collaborations with multiple diverse providers.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This work is funded by the National Institute on Aging Grant 1R03AG042648-01A1 for supporting this work. The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest and each author meets authorship requirement

We acknowledge the National Institute on Aging Grant AG042648-01A1 for supporting this work. The paper has not published at any other places and is not currently being reviewed by any other journal. The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest, and each author meets authorship requirement.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Shubing Cai, Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Rochester School of Medicine, 265 Crittenden Blvd., CU 420644, Rochester, New York 14642, Phone: 585-275-6617, Fax: (585) 461-4532.

Susan C. Miller, Professor of Health Services, Policy & Practice (Research), Center for Gerontology & Healthcare Research, Brown University School of Public Health, 121 South Main Street, Providence, RI 02912, Phone: (401) 863-9216.

Pedro L. Gozalo, Associate Professor of Health Services, Policy & Practice, Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research, Brown University School of Public Health, 121 South Main St, Box G-S121-6, Providence, RI 02912, Phone: (401) 863-7795

References

- 1.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. Jama. 2013 Feb 6;309(5):470–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bercovitz A, Gruber-Baldini AL, Burton LC, Hebel JR. Healthcare utilization of nursing home residents: comparison between decedents and survivors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005 Dec;53(12):2069–2075. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gozalo PL, Miller SC. Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Health services research. 2007 Apr;42(2):587–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller SC, Gozalo P, Mor V. Hospice enrollment and hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Am J Med. 2001 Jul;111(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mor V, Papandonatos G, Miller SC. End-of-life hospitalization for African American and non-Latino white nursing home residents: variation by race and a facility’s racial composition. Journal of palliative medicine. 2005 Feb;8(1):58–68. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saliba D, Kington R, Buchanan J, et al. Appropriateness of the decision to transfer nursing facility residents to the hospital. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000 Feb;48(2):154–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouslander JG, Berenson RA. Reducing unnecessary hospitalizations of nursing home residents. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Sep 29;365(13):1165–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1105449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Annals of internal medicine. 1993 Feb 1;118(3):219–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ouslander JG, Weinberg AD, Phillips V. Inappropriate hospitalization of nursing facility residents: a symptom of a sick system of care for frail older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000 Feb;48(2):230–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grabowski DC, O’Malley AJ, Barhydt NR. The costs and potential savings associated with nursing home hospitalizations. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2007 Nov-Dec;26(6):1753–1761. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2010 Jan-Feb;29(1):57–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dosa D. Should I hospitalize my resident with nursing home-acquired pneumonia? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005 Sep-Oct;6(5):327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casarett D, Karlawish J, Morales K, Crowley R, Mirsch T, Asch DA. Improving the use of hospice services in nursing homes: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2005 Jul 13;294(2):211–217. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevenson DG, Bramson JS. Hospice care in the nursing home setting: a review of the literature. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2009 Sep;38(3):440–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller SC, Gozalo P, Mor V. Outcomes and Utilization for Hospice and Non-Hospice Nursing Facility Decedents. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [access on Sep 18, 2011]. http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2000/oututil.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller SC. A model for successful nursing home-hospice partnerships. Journal of palliative medicine. 2010 May;13(5):525–533. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller SC, Kiely DK, Teno JM, Connor SR, Mitchell SL. Hospice care for patients with dementia: does volume make a difference? Journal of pain and symptom management. 2008 Mar;35(3):283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker-Oliver D, Bickel D. Nursing home experience with hospice. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2002 Mar-Apr;3(2):46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zerzan J, Stearns S, Hanson L. Access to palliative care and hospice in nursing homes. Jama. 2000 Nov 15;284(19):2489–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller SC, Mor VN. The role of hospice care in the nursing home setting. Journal of palliative medicine. 2002 Apr;5(2):271–277. doi: 10.1089/109662102753641269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. 2017 Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/congressional-testimony/05182017_medpac_testimony_march_report_wm.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 22.Gozalo P, Plotzke M, Mor V, Miller SC, Teno JM. Changes in Medicare costs with the growth of hospice care in nursing homes. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 May 07;372(19):1823–1831. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1408705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller SC, Lima J, Gozalo PL, Mor V. The growth of hospice care in U.S. nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010 Aug;58(8):1481–1488. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MedPAC. Hospice services. 2012 available at: http://medpac.gov/chapters/Mar12_Ch11.pdf.

- 25.Wooldridge J. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data The MIT Press. Cambridge; Massachusetts: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller SC, Mor V. The opportunity for collaborative care provision: the presence of nursing home/hospice collaborations in the U.S. states. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2004 Dec;28(6):537–547. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watt CK. Hospices within nursing homes: should a long-term care facility wear both hats? A commentary. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 1997 Mar-Apr;14(2):63–65. doi: 10.1177/104990919701400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Requirements for Long Term Care Facilities. Hospice Services; 2013. Medicare and Medicaid Programs. 78 Fed. Reg. 38594. Available at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-06-27/pdf/2013-15313.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Office of Inspector General. Medicare Hospice That Focus on Nursing Facility Residents. 2011 available at: http://www.scnursinghomelaw.com/uploads/file/Medicare%20Hospice%20OIG%20Report.pdf.