Abstract

People from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, including low- and middle-income countries, account for a third of new HIV diagnoses in Australia and are a priority for HIV prevention and treatment programs. We describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in the Australian HIV Observational Database (AHOD) and compare disease outcomes, progression to AIDS and treatment outcomes of those born in low- and middle-income countries, with those born in high-income countries and Australia. All participants enrolled in AHOD sites where country of birth is routinely collected were included in the study. Age, CD4 count, HIV viral load, antiretroviral therapy, hepatitis co-infection, all-cause mortality and AIDS illness were analysed. Of 2403 eligible participants, 77.3% were Australian born, 13.7% born in high-income countries and 9.0% born in middle- or low-income countries. Those born in Australia or high-income countries were more likely to be male (96%) than those from middle- or low-income countries (76%), p < .0001 and more likely to have acquired HIV via male to male sexual contact (77%; 79%) compared with those from middle- or low-income countries (50%), p < .0001. At enrolment, mean CD4 cell count was higher in Australian born (528 cells/µL) than both those born in high-income countries (468 cells/µL) and those born in middle- and low-income countries (451 cells/µL), p < .0001; whereas the mean HIV RNA level (log10 copies/mL) was similar in all three groups (4.44, 4.76 and 4.26, respectively), p = .19. There was no difference in adjusted incidence risk ratios for all-cause mortality and AIDS incidence in all three groups, p = .39. These findings reflect successful outcomes of people born in low- and middle-income countries once engaged in HIV care.

Keywords: HIV, migrant, low- and middle-income country, CD4 cell count, AIDS mortality, AIDS incidence

Introduction

In Australia, there are an estimated 26,800 people living with HIV. Sexual health clinics in Australia provide care at no charge to attendees, and specialist general practitioners and tertiary referral services can provide care free of charge under the Medicare system for citizens and permanent visa holders (Australian Government, Department of Human Services, 2013). The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme provides subsided antiretroviral therapy (ART) to those entitled to Medicare; however, people who do not have Medicare may access treatment through a range of options (National association of people with HIV Australia, 2014). People born outside of Australia accounted for just under half (45.8%) of HIV infections diagnosed in 2013 and of these, almost three-quarters (74.4%) were in people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, including low- and middle-income countries, with 10% speaking a language other than English at home (The Kirby Institute, 2014). Newly diagnosed infections attributable to heterosexual contact accounted for nearly a quarter (24.6%) of HIV infections from 2009 to 2013. Of these, 37% were in men and women who acquired infection in a high prevalence country, with the majority of cases coming from low- and middle-income regions of Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia (The Kirby Institute, 2014).

A systematic review (Alvarez-del Arco et al., 2012) on HIV testing and counselling for migrant populations living in high-income countries, found migrants have a higher frequency of delayed HIV diagnosis and are more vulnerable to the negative effects of disclosure of HIV status, fearing stigma and discrimination from their communities. Migrants can face additional barriers relating to health literacy in accessing health care and using health information. Of people born in non-English speaking countries, only one-third had adequate or better health literacy when tested in English compared with 43% of people born in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009). Other barriers that impact on migrant populations accessing HIV care include financial constraints, discrimination and social isolation (Asante, Korner, McMahon, Sabri, & Kippax, 2009; Vlassoff & Ali, 2011). The Australian Government Seventh National HIV Strategy 2014–2017 (Commonwealth of Australia, 2014) recognises people from high HIV prevalence countries and their partners as a priority for HIV prevention and treatment programs, emphasising the importance of timely diagnosis and commencement of ART.

In high-income settings, delayed HIV diagnosis, or late presentation, is defined as presenting for care with a CD4 cell count <350 cells/µL or with an AIDS defining event and late presentation is associated with lower survival and early mortality (Antinori et al., 2011). In Australia, over one-third (38.8%) of patients are late presenters (The Kirby Institute, 2014). A review (Hall et al., 2013), including patients in Australia reported that those with a heterosexual mode of transmission had a higher percentage of delayed HIV diagnosis and lower percentage of linkage to care.

The aim of this study was to describe the demographics and clinical characteristics of Australian HIV Observational Database (AHOD) cohort participants born in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) compared with participants born in Australia (AUS) and other high-income countries (HIC). Treatment outcomes, disease outcomes including all-cause mortality and progression to AIDS were examined.

Methods

Study population

The AHOD is an observational clinical cohort study of participants with HIV infection attending specialised general practitioner sites, sexual health clinics and tertiary referral centres, totalling 31 clinical sites. A detailed description of the study methodology is described elsewhere (The Australian HIV Observational Database, 2002) .This analysis includes all participants enrolled in AHOD between 1999 and 2013 who attended a clinical site that routinely collected country of birth (COB) information (defined as the percentage of missing COB information of less than 50%). We categorised COB into country-specific income groupings based on World Bank gross national income (GNI) indicators (The World Bank, n.d.). We adopted a similar categorisation method as used in prior AHOD publications (Wright et al., 2013). AHOD participants were stratified into those born in LMIC, born in other HIC and born in Australia.

Statistical analysis

We tabulated participant characteristics summarised by income groupings. Factors considered in analysis included age, mode of HIV exposure, COB, hepatitis co-infection, history of ART, pre- and post-ART CD4 cell count and plasma HIV RNA level.

Statistically significant differences between proportions for categorical variables compared across income groupings were assessed using a chi-square test, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences in mean values for continuous variables. We determined statistical significance for both tests at the α = 0.05 cut-off point. Cox proportional hazard models and Kaplan–Meier survival methods were used to evaluate differences in disease progression, as well as clinical HIV-related outcomes. Specifically, we used Cox proportional hazard models to assess any differences across COB income groupings in hazard for any change in ART, hazard of first viral suppression (defined as HIV RNA viral load <400 copies/mL), and hazard of treatment failure (defined as HIV RNA viral load >1000 copies/mL). The ART regimen analysed was the ART regimen received at enrolment, or the first ART regimen initiated after enrolment. Kaplan–Meier methods were used to assess differences in survival distributions for participants lost-to-follow-up and incident clinical endpoints (composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or new AIDS illness). Our primary analysis variable was income grouping and models were adjusted a priori for age, sex, mode of exposure, hepatitis co-infection, clinical care setting, CD4 cell count and HIV RNA viral level at ART initiation, year of ART initiation and an indicator for mono/duo antiretroviral exposure prior to ART treatment initiation. No form of multivariable model selection was performed for these analyses. For all analyses, we defined origin time as cohort enrolment date. Participants were followed up until occurrence of endpoint, their last clinical visit or 31 March 2013 (administration censor). Participants were considered lost-to-follow-up if they had not been seen at the clinic for at least one year. Participants with at least one follow-up visit were considered in the analyses for disease or treatment-related outcomes.

Results

Of the 3894 participants enrolled in AHOD, 2721 (70%) were eligible for analysis. A total of 1173 were excluded from the analysis due to enrolment at a site where COB information was not captured in the electronic patient management system. Currently, 20 (65%) of the 31 AHOD sites routinely collect COB information. Of the sites that collect COB information, the median percentage of missing COB was 10%. Three-quarters (77.3%) of the participants were Australian born, 13.7% born in HIC and 9.0% born in LMIC. The majority of those from LMIC were born in East-Asia and the Pacific (51%) or Sub-Saharan Africa (22%).

Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median age at enrolment of those born in LMIC was 40.5 years (interquartile range 39.2–45.5) which is younger (p < .0001) than those born in AUS and HIC (42.4 [35.0–48.5] years and 45.6 [37.2–52.1] years), respectively. There were a higher proportion of females born in LMIC compared with AUS and HIC (24%, 4% and4%, respectively), p < .0001. A higher proportion of people born in LMIC reported heterosexual mode of exposure compared with AUS and HIC (38%, 14% and13%, respectively), p < .0001. A higher proportion of participants (46%) from HIC accessed HIV care from Sexual Health Clinics compared with participants from LMIC (33%) and Australian born participants (35%), (p = .0004). There was also a similar prevalence of hepatitis B co-infection (p = .75) and hepatitis C co-infection (p = .33) in all three groups. Proportionately more people from LMIC enrolled in the second phase of the AHOD cohort from 2007 to 2013 (p < .0001).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in Australian HIV Observational Database cohort by country of birth World Bank income grouping.

| Australian born, N = 1857 N (%) |

Overseas born: HIC, N = 330 N (%) |

Overseas born: LMIC N = 216 N (%) |

p-Value | Country of birth missing, N = 318 N (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region of birth | East Asia and Pacific | – | 96 (29) | 111 (51) | n/a | – |

| South Asia | – | – | 26 (12) | – | ||

| Europe and Central Asia | – | 200 (61) | 8 (4) | – | ||

| Middle East and North Africa | – | 1 (0) | 7 (3) | – | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | – | – | 48 (22) | – | ||

| North America | – | 24 (7) | – | – | ||

| Latin America and Caribbean | – | 9 (3) | 16 (7) | – | ||

| Era of cohort enrolment | 1999–2006 | 1294 (70) | 218 (66) | 103 (48) | <.0001 | 251 (79) |

| 2007–2013 | 563 (30) | 112 (34) | 113 (52) | 67 (21) | ||

| Sex | Male | 1779 (96) | 317 (96) | 165 (76) | <.0001 | 292 (92) |

| Female | 78 (4) | 13 (4) | 51 (24) | 26 (8) | ||

| Mode of HIV exposure | Male to male sexual contact | 1431 (77) | 262 (79) | 109 (50) | <.0001 | 224 (70) |

| Heterosexual | 260 (14) | 42 (13) | 83 (38) | 45 (14) | ||

| Injecting drug use | 102 (5) | 16 (5) | 7 (3) | 35 (11) | ||

| Other | 34 (2) | 8 (2) | 14 (6) | 10 (3) | ||

| Unknown | 30 (2) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 4 (1) | ||

| HIV care setting | General Practice | 835 (45) | 107 (32) | 99 (46) | .0004 | 102 (32) |

| Hospital | 375 (20) | 72 (22) | 45 (21) | 15 (5) | ||

| Sexual Health Clinic | 647 (35) | 151 (46) | 72 (33) | 201 (63) | ||

| ART regimen at enrolment (2 × NRTI + __) | NNRTI | 600 (32) | 122 (37) | 82 (38) | .60 | 88 (28) |

| PI | 420 (23) | 75 (23) | 38 (18) | 72 (23) | ||

| II | 24 (1) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 4(1) | ||

| Other | 270 (13) | 42 (12) | 29 (13) | 43 (15) | ||

| Naïve/Off ART | 543 (29) | 90 (27) | 66 (31) | 111 (35) | ||

| Hepatitis B | Yes | 68 (4) | 15 (5) | 11 (5) | .75 | 21 (7) |

| No | 1447 (78) | 260 (79) | 166 (77) | 222 (70) | ||

| Not tested | 342 (18) | 55 (17) | 39 (18) | 75 (24) | ||

| Hepatitis C | Yes | 200 (11) | 31 (9) | 16 (7) | .36 | 53 (17) |

| No | 1425 (77) | 265 (80) | 176 (81) | 265 (83) | ||

| Not tested | 232 (12) | 34 (10) | 24 (11) | |||

| AIDS illness (after enrolment) | Yes | 398 (21) | 82 (25) | 45 (21) | .36 | 53 (17) |

| No | 1459 (79) | 248 (75) | 171 (79) | 265 (83) |

Notes: ART, antiretroviral therapy; NRTI, nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PI, protease inhibitors; II, integrase inhibitors.

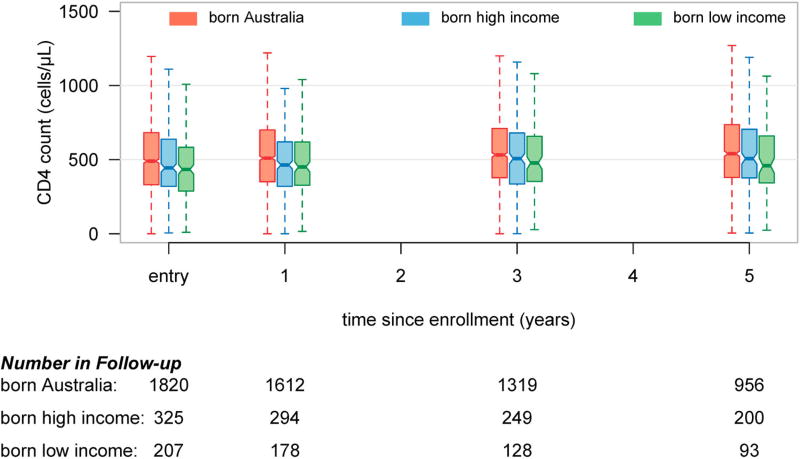

The CD4 cell count and HIV RNA levels at enrolment are presented in Table 2. Overall those born in LMIC had a lower mean CD4 cell count at AHOD enrolment, and from entry over time (Figure 1) than those born in AUS and HIC (451 cells/µL, 528 cells/µL and 468 cells/µL, respectively), p < .0001. Of participants receiving ART at cohort enrolment, those born in LMIC had a lower mean CD4 cell count at AHOD entry (p < .0001) than those born in AUS and HIC (425 cells/µL, 532 cells/µL and 477 cells/µL, respectively). Mean HIV RNA level (log10 copies/mL) at AHOD enrolment was similar (p = .19) across all three groups (4.26 log, 4.44 log and 4.76 log, respectively). There were no significant differences between type of ART regimen when comparing nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) plus either non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors (PI), integrase inhibitor (II) or other ART (p = .60).

Table 2.

Continuous variables for CD4 cell count and HIV RNA of participants in Australian HIV Observational Database cohort by country of birth World Bank income grouping.

| Australian born, N = 1857 |

Overseas born: HIC, N = 330 |

Overseas born: LMIC, N = 216 |

p-Value | Country of birth missing, N = 318 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 cell count at enrolment | Mean | 528 | 486 | 451 | <.0001 | 508 |

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 490 [330.5, 682] | 444 [320, 638] | 434 [286, 586] | 460 [290, 655] | ||

| CD4 cell count at enrolment On ART | Mean | 532.2 | 476.97 | 425.05 | <.0001 | 513.95 |

| Mediana [Q1, Q3] | 493 [322–694] | 440 [290–638] | 381 [259–555] | 470 [273–655] | ||

| HIV RNA (log 10 copies/mL) at enrolment | Mean | 4.44 | 4.76 | 4.26 | .19 | 4.68 |

| Mediana [Q1, Q3] | 2.6 [1.7, 3.92] | 2.6 [1.7, 3.98] | 2.46 [1.7, 3.56] | 2.6 [1.7, 4.2] |

Q1, Q3 – Interquartile range.

Figure 1.

Boxplot summary of participants CD4 cell count at various time points since Australian HIV Observational Database cohort enrolment. Data stratified by country of birth World Bank income groupings.

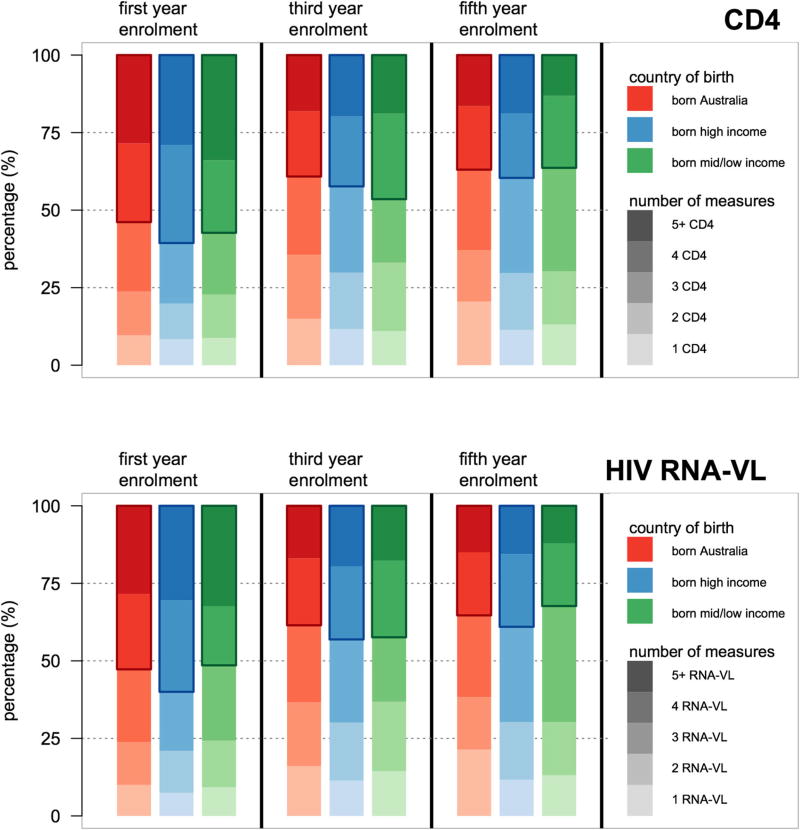

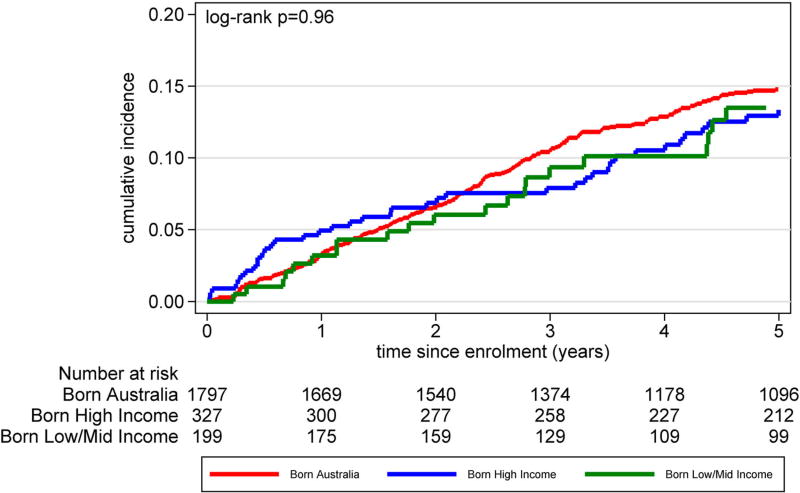

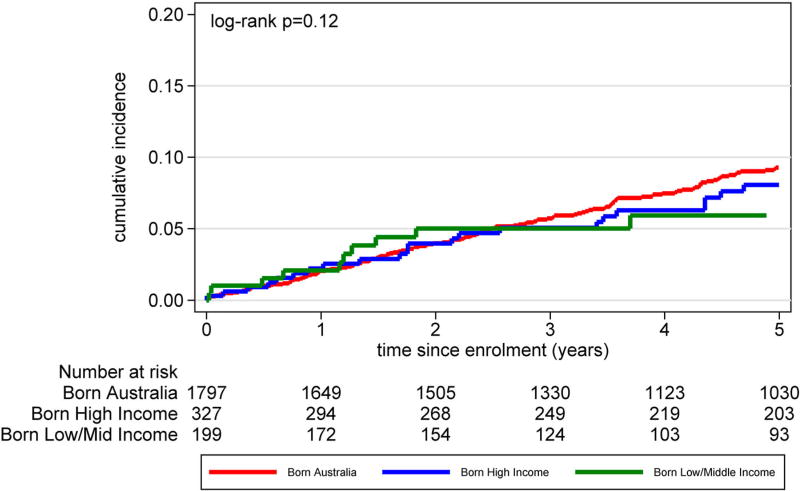

Table 3 reports Cox proportional hazard ratios for COB income groupings for the hazard ratios of changing of ART regimen, hazard of suppressing HIV RNA viral load and hazard of first virological failure (HIV RNA viral load >1000 copies/mL) following viral suppression. In multivariable adjusted analyses, no statistically significant differences between hazards were found. Among the three groups, there were minimal proportional differences in terms of accessing HIV monitoring care (Figure 2) and differences in time to loss-to-follow-up (Figure 3) (log-rank p = .96). Cumulative incidence for a composite clinical endpoint of all-cause mortality or new AIDS incidence from enrolment (Figure 4) were similar among all three groups (log-rank p = .12)

Table 3.

Hazard ratio of any antiretroviral therapy modification, or achieving virological suppression, or developing virological failure of participants in the Australian HIV Observational Database by country of birth World Bank income groupings.

| Event/ person years |

Univariate hazard ratio [95% confidence interval] |

p-Value (global) |

Adjusted hazard ratio [95% confidence interval] |

p-Value (global) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time from initiation of ART at enrolment to any ART changea | AUS | 951/4404 | 1.00 | .11 | 1.00 | .41 |

| HIC | 171/781 | 1.01 [0.86–1.19] | 0.99 [0.84–1.16] | |||

| LMIC | 88/512 | 0.79 [0.64–0.99] | 0.86 [0.68–1.08] | |||

| Time from initiation of ART at enrolment to first plasma HIV RNA <400 copies/mLb | AUS | 1333/651 | 1.00 | .37 | 1.00 | .79 |

| HIC | 235/107 | 1.07 [0.93–1.22] | 1.04 [0.90–1.20] | |||

| LMIC | 147/55 | 1.11 [0.94–1.32] | 0.97 [0.81–1.16] | |||

| Time from first suppressed plasma HIV RNA levelc to virological failure HIV RNA >1000 copies/mLd | AUS | 415/3702 | 1.00 | .03 | 1.00 | .18 |

| HIC | 62/735 | 0.77 [0.59–1.00] | 0.80 [0.61–1.04] | |||

| LMIC | 31/396 | 0.69 [0.48–1.00] | 0.83 [0.57–1.21] |

Adjusted for sex, age, injecting drug use, Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis C virus, cell count at antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation, year of ART, clinical care setting, indicator for first-line ART regimen.

Adjusted for adjusted for sex, age, injecting drug use, Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis C virus, cell count at ART initiation, HIV RNA viral load at ART initiation, year of ART, clinical care setting, indicator for first-line ART regimen.

For the regimen commenced at AHOD cohort enrolment.

Adjusted for sex, age, injecting drug use, Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis C virus, cell count at ART initiation, year of ART, clinical care setting.

Figure 2.

Number of participant HIV monitoring measurements (CD4 cell count and HIV RNA viral load) taken per year stratified by time since Australian HIV Observational Database cohort enrolment and country of birth World Bank income grouping.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of participants lost-to-follow-up (differences in t = 0 numbers due to no follow-up visit recorded), defined as not seen at health service for >365 days, by country of birth World Bank income grouping.

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence clinical endpoint (all-cause mortality and new AIDS illness) of participants by time since Australian HIV Observational Database cohort enrolment by country of birth World Bank income grouping.

Discussion

This study examined the HIV treatment and disease outcomes of migrants to Australia from LMIC, who comprise approximately 10% of the AHOD cohort. This group was younger, had a higher proportion of women and heterosexual mode of transmission compared with people from HIC and Australia. The majority of people from LMIC in this cohort were from South Asia and the Pacific or Sub-Saharan Africa. This reflects patterns of migration to Australia from LMIC, including people who arrived as refugees (Australian Government, Department of Immigration and Border Protection, 2014; The World Bank, 2011). These findings are consistent with a previous Australian study (McPherson, McMahon, Moreton, & Ward, 2011) and reflective of the global pattern of the HIV epidemic in LMIC (AVERT, 2014). A higher proportion of people from HIC accessed sexual health clinics rather than general practice or tertiary referral services for HIV care compared with those born in LMIC or AUS in the AHOD cohort. However, another study of HIV in migrant groups in New South Wales reported a higher proportion of HIV diagnosis in people from LMIC and HIC were made at sexual health clinics or immigration services (McPherson et al., 2011).

We found that once engaged with a health-care service, there were no differences among those born in LMIC, HIC or AUS with respect to routine monitoring of HIV infection or rates of loss-to-follow-up (Figures 2 and 3). This is in contrast to a study from Italy that found a higher proportion of migrants were lost-to-follow-up (Saracino et al., 2013). That study found differences between country of origin groups, with migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa having higher lost-to-follow-up rates and migrants from Asia having better follow-up rates compared with Europeans (The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort, 2013).

Other studies have found that migrants from LMIC are over-represented among those presenting with a delayed HIV diagnosis (Oliva et al., 2013; The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort, 2013; Wilson et al., 2014), and experience a resultant increased risk of chronic morbidity and mortality (Antinori et al., 2011), including higher rates of AIDS defining illness in the first year of ART (The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort, 2013). This study examined treatment outcomes and mortality from entry into the AHOD cohort rather than from date of HIV diagnosis. Those born in LMIC had a lower mean CD4 cell count at enrolment into the cohort compared to those born in HIC and AUS. This is suggestive of delayed HIV diagnosis; however, there were no differences in all-cause mortality and new AIDS incidence when comparing those born in LMIC, HIMC and AUS. This is similar to a finding by treatment naïve migrants from LMIC to Spain (Monge et al., 2012), which found that although migrants were more likely to have delayed HIV diagnosis there were no differences in mortality. We also found no significant differences in the use of ART, type of ART regimens, time to change in ART regimen, time taken to achieve undetectable HIV viral load or time to virological failure between LMIC, HIC or Australian born groups. These findings are suggestive of successful engagement in care for migrants from LMIC in the Australian context.

This study has several limitations. Of the total sites participating in AHOD, only 24 routinely collect country birth data, representing just over three-quarters (77%) of the total study sites. All treatment outcomes, disease outcomes including all-cause mortality and progression to AIDS were examined from enrolment into the AHOD cohort; therefore, this study did not examine CD4 cell count, treatment history, AIDS defining events or presentation with advanced HIV disease or AIDS at the time of HIV diagnosis. Similarly, data on date of arrival into Australia and the recency of HIV infection were not available. There is heterogeneity in the migrant populations from both LMIC and HIC and specific subpopulations were not examined.

Our findings suggest that once engaged in HIV care in Australia and on ART there was no difference in outcomes between people born in LMIC, HIC or Australia. There is an ongoing need to develop responses for maximising engagement with health-care information for migrant populations. Ongoing work is needed to ensure timely entry into the HIV care cascade for migrants from low- and middle-income countries.

Acknowledgments

Australian HIV Observational Database contributors (asterisks indicate steering committee members in 2013) are given as follows: New South Wales: D. Ellis, General Medical Practice, Coffs Harbour; M. Bloch, S. Agrawal, T. Vincent, Holds-worth House Medical Practice, Darlinghurst; D. Allen, J.L. Little, Holden Street Clinic, Gosford; D. Smith, Lismore Sexual Health & AIDS Services, Lismore; D. Baker*, V. Ieroklis, East Sydney Doctors, Surry Hills; D.J. Templeton*, C.C. O’Connor, S. Phan, RPA Sexual Health Clinic, Camperdown; E. Jackson, K. McCallum, Blue Mountains Sexual Health and HIV Clinic, Katoomba; M. Grotowski, S. Taylor, Tamworth Sexual Health Service, Tamworth; D. Cooper, A. Carr, F. Lee, K. Hesse, St Vincent’s Hospital, Darlinghurst; R. Finlayson, A. Patel, S. Gupta, Taylor Square Private Clinic, Darlinghurst; R. Varma, J. Shakeshaft, Nepean Sexual Health and HIV Clinic, Penrith; K. Brown, V. McGrath, S. Halligan, N. ArvelaIllawarra Sexual Health Service, Warrawong; L. Wray, R. Foster, H. Lu, Sydney Sexual Health Centre, Sydney; D. Couldwell, Parramatta Sexual Health Clinic; D.E. Smith*, V. Furner Albion Street Centre; Clinic 16 – Royal North Shore Hospital; S. Fernando, Dubbo Sexual Health Centre, Dubbo; J. Watson*, National Association of People living with HIV/AIDS; C. Lawrence*, National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation; B. Mulhall*, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of Sydney; M. Law*, K. Petoumenos*, S. Wright*, H. McManus*, C. Bendall*, M. Boyd*, The Kirby Institute, University of NSW. Northern Territory: N. Ryder, R. Payne, Communicable Disease Centre, Royal Darwin Hospital, Darwin. Queensland: M. O’Sullivan, S. White, Gold Coast Sexual Health Clinic, Miami; D. Russell, S. Doyle-Adams, C. Cashman, Cairns Sexual Health Service, Cairns; D. Sowden, K. Taing, K. McGill, Clinic 87, Sunshine Coast-Wide Bay Health Service District, Nambour; D. Orth, D. Youds, Gladstone Road Medical Centre, Highgate Hill; M. Kelly, D. Rowling, N. Latch, Brisbane Sexual Health and HIV Service, Brisbane; B. Dickson*, CaraData. South Australia: W. Donohue, O’Brien Street General Practice, Adelaide. Victoria: R. Moore, S. Edwards, R. Woolstencroft Northside Clinic, North Fitzroy; N.J. Roth*, H. Lau, Prahran Market Clinic, South Yarra; T. Read, J. Silvers*, W. Zeng, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Melbourne; J. Hoy*, K. Watson*, M. Bryant, S. Price, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne; I. Woolley, M. Giles*, T. Korman, J. Williams*, Monash Medical Centre, Clayton. Western Australia: D. Nolan, J. Robinson, Department of Clinical Immunology, Royal Perth Hospital, Perth. New Zealand: G. Mills, C. Wharry, Waikato District Hospital Hamilton; N. Raymond, K. Bargh, Wellington Hospital, Wellington.

Coding of Death Form (CoDe) reviewers are given as follows:

AHOD reviewers are given as follows: D. Sowden, J. Hoy, L. Wray, K. Morwood, T. Read, N. Roth, I. Woolley, K. Choong, C. O’Connor, M. Boyd..

Funding

The Australian HIV Observational Database is funded as part of the Asia Pacific HIV Observational Database, a program of The Foundation for AIDS Research, amfAR, and is supported in part by a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (Grant No. U01-AI069907) and by unconditional grants from Merck Sharp & Dohme; Gilead Sciences; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Boehringer Ingelheim; ViiV Australia; Janssen-Cilag. The Kirby Institute is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales. Jennifer Hoy’s institution receives funding for her participation in Advisory Boards for Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Ian Wolley has received research funds from Gilead Sciences and MSD, consulting funds from Bristol Myers Squibb and Gilead Sciences and chairing fees from Abbott and MSD. Conference support from MSD, Viiv Healthcare and Abbott. The rest of the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alvarez-del Arco D, Monge S, Azcoaga A, Rio I, Hernando V, Gonzalez C. HIV testing and counselling for migrant populations living in high-income countries: A systematic review. The European Journal of Public Health. 2012;23(6):1039–1045. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Coenen T, Costagiola D, Dedes N, Ellefson M, Gatell J. Late presentation of HIV infection: A consensus definition. HIV Medicine. 2011;12(1):61–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asante A, Korner H, McMahon T, Sabri W, Kippax S. Periodic survey of HIV knowledge and use of health services among people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds 2006–2008 (Monograph 2/2009): National centre in HIV social research. Sydney: The University of New South Wales; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Health literacy. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/LookupAttach/4102.0Publication30.06.093/$File/41020_Healthliteracy.pdf.

- Australian Government, Department of Human Services. Eligibility for Medicare card. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.humanservices.gov.au/customer/enablers/medicare/medicare-card/eligibility-for-medicare-card.

- Australian Government, Department of Immigration and Border Protection. Fact Sheet 60 – Australia’s Refugee and Humanitarian Programme. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/60refugee.htm.

- AVERT. Global HIV & AIDS epidemic. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.avert.org/global-hiv-aids-epidemic.htm.

- Commonwealth of Australia. Seventh national HIV strategy 2014–2017. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/8E87E65EEF535B02CA257BF0001A4EB6/$File/HIV-Strategy2014-v3.pdf.

- Hall HI, Halverson J, Wilson DP, Suligoi B, Diez M, Le Vu S. Late diagnosis and entry to care after diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus infection: A country comparison. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson ME, McMahon T, Moreton RJ, Ward KA. Using HIV notification data to identify priority migrant groups for HIV prevention, New South Wales 2000–2008. Communicable Diseases Intelligence Quarterly Report. 2011;35(2):185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge S, Alejos B, Dronda F, Del Romero J, Iribarren JA, Pulido F. Inequalities in HIV disease management and progression in migrants from Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa living in Spain. HIV Medicine. 2012;14(5):273–283. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of People with HIV Australia. How to access HIV care and treatment in Australia. 2014 Retrieved from http://napwha.org.au/health-treatment/hiv-treatment/how-access-hiv-care-and-treatment-australia.

- Oliva J, Diez M, Galindo S, Cevallos C, Izquierdo A, Cereijo J. Predictors of advanced disease and late presentation in new HIV diagnoses reported to the surveillance system in Spain. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2013;28(2):116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saracino A, Tartaglia A, Trillo G, Muschitiello C, Bellacosa C, Brindicci G. Late presentation and loss to follow-up of immigrants newly diagnosed with HIV in the HAART era. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2013;16(4):751–755. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9863-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Influence of geographical origin and ethnicity on mortality in patients on antiretroviral therapy in Canada, Europe, and the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2013;56(12):1800–1809. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Australian HIV Observational Database. Rates of combination antiretroviral treatment change in Australia, 1997–2000. HIV Medicine. 2002;3(1):28–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-2662.2001.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Kirby Institute. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia Annual Surveillance Report 2014. Sydney: The Kirby Institute, The University of New South Wales; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Migration and remittances fact book 2011. (2) 2011 Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTLAC/Resources/Factbook2011-Ebook.pdf.

- The World Bank. World Bank GNI per capita Operational Database. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/OGHIST.xls.

- Vlassoff C, Ali F. HIV-related stigma among South Asians in Toronto. Ethnicity & Health. 2011;16(1):25–42. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2010.523456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K, Dray-Spira R, Aubriere C, Hamelin C, Spire B, Lert F. Frequency and correlates of late presentation for HIV infection in France: Older adults are a risk group – results from the ANRS-VESPA2 Study, France. AIDS Care. 2014;26(Suppl. 1):S83–S93. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.906554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S, Boyd MA, Yunihastuti E, Law M, Sirisanthana T, Hoy J. Rates and factors associated with major modifications to first-line combination antiretroviral therapy: Results from the Asia-Pacific region. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]