Abstract

Cardiac myocyte contraction is initiated by a set of intricately orchestrated electrical impulses, collectively known as action potentials (APs). Voltage-gated sodium channels (NaVs) are responsible for the upstroke and propagation of APs in excitable cells, including cardiomyocytes. NaVs consist of a single, pore-forming α subunit and two different β subunits. The β subunits are multifunctional cell adhesion molecules and channel modulators that have cell type and subcellular domain specific functional effects. Variants in SCN1B, the gene encoding the Nav-β1 and -β1B subunits, are linked to atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, e.g., Brugada syndrome, as well as to the early infantile epileptic encephalopathy Dravet syndrome, all of which put patients at risk for sudden death. Evidence over the past two decades has demonstrated that Nav-β1/β1B subunits play critical roles in cardiac myocyte physiology, in which they regulate tetrodotoxin-resistant and -sensitive sodium currents, potassium currents, and calcium handling, and that Nav-β1/β1B subunit dysfunction generates substrates for arrhythmias. This review will highlight the role of Nav-β1/β1B subunits in cardiac physiology and pathophysiology.

Keywords: sodium channel, B subunit, arrhythmia, epilepsy, cell adhesion, electrophysiology

Introduction

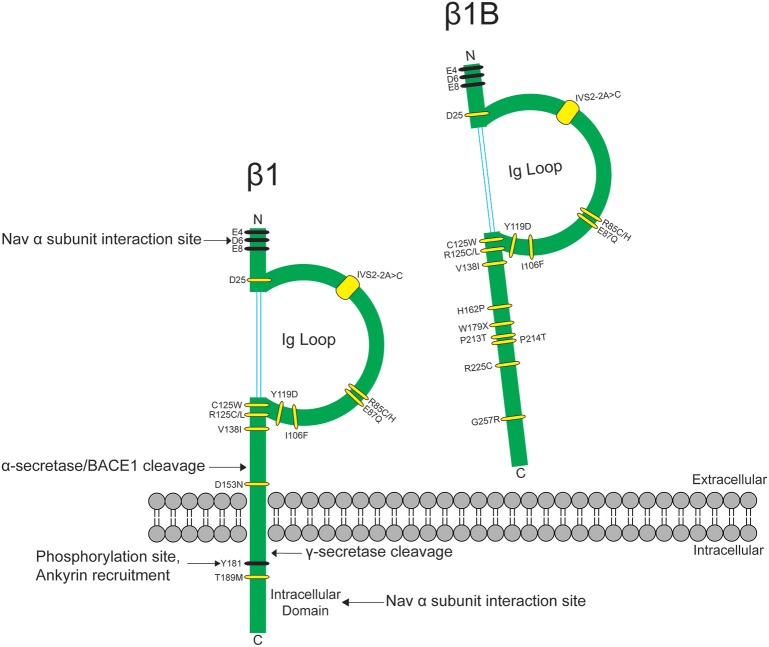

The heart contracts to pump blood throughout the body. It consists of specialized cells called cardiac myocytes (CMs), and contraction of CMs is initiated by electrical impulses called action potentials (APs) (Nerbonne and Kass, 2005). Cardiac APs are generated and propagated through the coordinated signaling of ion channels. Upon membrane depolarization, voltage-gated sodium channels (NaVs) activate and inactivate rapidly to allow sodium influx (Hille and Catterall, 2012). This is responsible for the rising phase and propagation of the AP in mammalian CMs (Nerbonne and Kass, 2005). NaVs are heterotrimeric transmembrane proteins consisting of one pore-forming α and two β subunits (Catterall, 2000). NaV-β subunits are expressed in mammalian heart (Isom et al., 1992; Makita et al., 1994) and their functional loss can result in electrical abnormalities that predispose patients to arrhythmias. Variants in the gene SCN1B, encoding the splice variants NaV-β1 and NaV-β1B, are implicated in a variety of inherited pathologies including epileptic encephalopathy (O'Malley and Isom, 2015), Brugada syndrome (BrS) (Watanabe et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2012), long-QT syndrome (LQTS) (Riuró et al., 2014), atrial arrhythmias (Watanabe et al., 2009), and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (Hu et al., 2012) (Figure 1, Table 1). Remarkably, regardless of disease etiology, patients with SCN1B mutations have an increased risk of sudden death. Classically, the NaV-β subunits were characterized as modulators of the NaV ion-conducting pore. However, from research over the past two decades, we know that NaV-β subunits are dynamic, multifunctional proteins that play important roles in cardiac physiology (O'Malley and Isom, 2015). Here, we will focus our review on the current understanding of NaV-β1/β1B function in CMs and discuss disease implications.

Figure 1.

SCN1B variants are linked to epilepsy syndromes and cardiac conduction diseases. SCN1B encodes Nav-β1 (left) and its secreted splice variant Nav-β1B (right). Sites for β1-α interaction, ankyrin binding, phosphorylation, and proteolytic cleavage are indicated. Ig: immunoglobulin. Human disease variants in β1 or β1B are indicated in yellow and are described in Table 1. Adapted from O'Malley and Isom (2015).

Table 1.

SCN1B variants linked to human disease.

| Disease | β1 | β1B |

|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation | R85H (Watanabe et al., 2009), D153N (Watanabe et al., 2009) | R85H (Watanabe et al., 2009), D153N (Watanabe et al., 2009) |

| Brugada syndrome | E87Q (Watanabe et al., 2008) | E87Q (Watanabe et al., 2008), H162P (Holst et al., 2012), W179X, R214Q (Holst et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2012) |

| Dravet syndrome | I106F (Ogiwara et al., 2012), Y119D (Ramadan et al., 2017), C121W (Wallace et al., 1998), R125C (Patino et al., 2009) | I106F (Ogiwara et al., 2012), Y119D (Ramadan et al., 2017),C121W (Wallace et al., 1998), R125C (Patino et al., 2009) |

| Generalized Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures Plus (GEFS+) | D25N (Orrico et al., 2009), R85H (Scheffer et al., 2006), R85C (Scheffer et al., 2006), R125L (Fendri-Kriaa et al., 2011), five amino acid deletions (IVS2-2A>C) (Audenaert et al., 2003) | D25N (Orrico et al., 2009), R85H (Scheffer et al., 2006), R85C (Scheffer et al., 2006), R125L (Fendri-Kriaa et al., 2011), five amino acid deletions (IVS2-2A>C) (Audenaert et al., 2003) |

| Idiopathic epilepsy | G257R (Patino et al., 2011) | |

| Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) | R214Q (Hu et al., 2012), R225C (Neubauer et al., in press) | |

| Sudden Unexpected Nocturnal Death Syndrome (SUNDS) | V138I (Liu et al., 2014), T189M (Liu et al., 2014) | V138I (Liu et al., 2014) |

| Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) | P213T (Riuró et al., 2014) |

NaVs are differentially expressed in cardiac myocytes

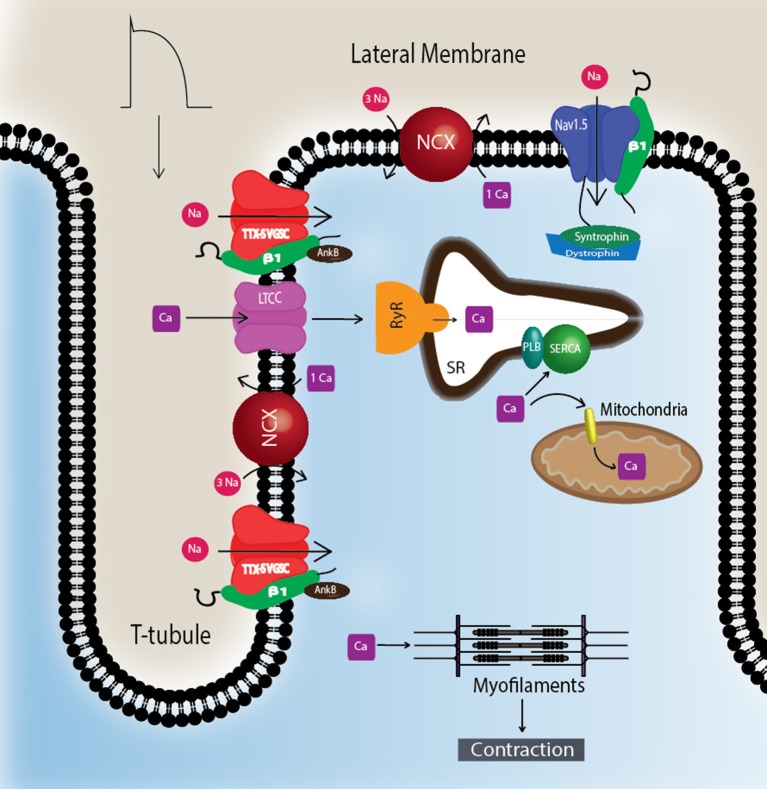

To understand Nav-β subunit physiology in heart, one must first consider the associated Nav-α subunits. Nav1.5 is the predominantly expressed NaV-α in CMs and the primary contributor to recorded sodium current (INa) density (Rogart et al., 1989; Gellens et al., 1992; Catterall, 2000; Maier et al., 2002). Nav1.5 is a “tetrodotoxin resistant (TTX-R)” channel (Catterall et al., 2005), in contrast to “TTX-sensitive (TTX-S)” channels, e.g., NaVs normally found in brain, for which TTX has nanomolar affinity (Catterall et al., 2005). TTX has micromolar affinity for Nav1.5 due to the presence of a cysteine residue in the selectivity filter in a position that is otherwise filled by an aromatic amino acid in TTX-S channels (Satin et al., 1992). TTX-S channels, Nav1.1, Nav1.3, and Nav1.6, are expressed in heart as well as in brain (Malhotra et al., 2001; Lopez-Santiago et al., 2007). They are preferentially localized in the transverse tubules (T-tubules) (Malhotra et al., 2001, 2002; Lopez-Santiago et al., 2007) where they are postulated to function in excitation-contraction coupling (Maier et al., 2002) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

TTX-S Navs are localized to T-tubules. TTX-S Navs, including Nav1.1, Nav1.3, and Nav1.6, are located at the T-tubules of CMs where they are thought to participate in the regulation of excitation-contraction coupling. Non-phosphorylated Nav-β1 subunits are co-localized with TTX-S Nav-α subunits at the T-tubules where they play roles in calcium signaling and homeostasis. Nav1.5 is localized at the lateral membrane as well as the ID (Figure 3). At the lateral membrane, Nav1.5 is complexed with syntrophin and dystrophin. Abbreviations: L-type calcium channel (LTCC), phospholamban (PLB), ryanodine receptor (RyR), sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX), transverse tubules (T-tubule).

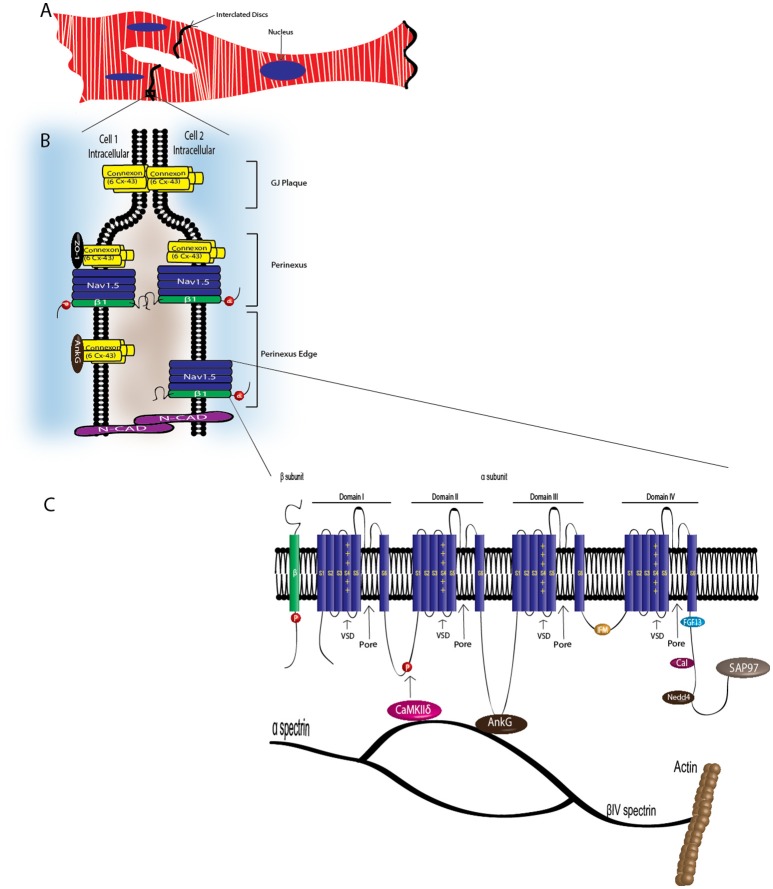

CMs associate at the intercalated disk (ID), where adherens junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes participate in intercellular communication (Vermij et al., 2017) (Figure 3A). Nav1.5 channels cluster at cell–cell junction sites at the ID, where they co-localize with the cardiac gap junction (GJ) protein, connexin-43 (Cx43) (Maier et al., 2002, 2004) (Figure 3B). Nav1.5 clustering may contribute to rapid AP conduction from cell-to-cell, similar to the node-to-node saltatory conducting function of TTX-S NaVs in myelinated nerves (Freeman et al., 2016). Nav1.5 channels are also expressed at the CM lateral membrane (Figure 2), where they have differing biophysical properties and binding partners from those at the ID (Lin et al., 2011; Petitprez et al., 2011; Shy et al., 2013), suggesting two distinct Nav1.5 pools.

Figure 3.

VGSC complexes at the cardiac intercalated disk. CMs associate at the ID, where Nav1.5, Nav-β1 subunits, adherens junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes define intercellular communication. (A) Associated CMs. (B) Proposed model of the GJ plaque, perinexus, and perinexus edge. Nav-β1 subunits at the ID are tyrosine phosphorylated, possibly through Fyn kinase activation, and may function in cell–cell adhesion in the perinexus and perinexus edge. (C) At the ID, Nav1.5 associates with a multi-protein complex (also see Table 2). The S4 segment of each Nav-α subunit homologous domain forms the voltage sensing domain (VSD) and segments 5 and 6 in each domain create the ion-conducting pore. Three hydrophobic amino acids, IFM, form the inactivation gate. Abbreviations: Ankyrin-G (AnkG), Calmodulin (Cal), Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKIIδ), Fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 1B (FHF1B), N-Cadherin (N-Cad), Nedd4-like-ubiqutin-protein ligases (Nedd4), Synapse-associated protein 97 (SAP97).

Cardiac NaVs form multi-protein complexes

NaV-α subunits interact with multi-protein complexes that are subcellular domain specific in heart. These interactions, which involve Nav-β1, as discussed throughout this review, are essential for proper cardiac electrical signaling (Figure 3C, Table 2). Ankyrin-G, a cytoskeletal adaptor protein, is necessary for normal expression of Nav1.5 and coupling of the channel to the actin cytoskeleton (Mohler et al., 2004). A human SCN5A BrS variant eliminates Nav1.5-ankyrin-G interactions (Mohler et al., 2004). This mutation, located in the Nav1.5 DII–III loop, prevents channel cell surface expression in ventricular CMs and alters channel properties. In agreement with this result, rat CMs with reduced expression of ankyrin-G have reduced levels of Nav1.5 expression and INa. Abnormal Nav1.5 localization can be rescued in ankyrin-G deficient CMs through exogenous over-expression of ankyrin-G (Lowe et al., 2008). Ankyrin-G recruits βIV spectrin, which forms important scaffolding structures and plays a role in the maintenance and integrity of the plasma membrane and cytoskeleton (Yang et al., 2007). βIV spectrin associates with and targets a subpopulation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKIIδ) to the ID to phosphorylate a critical serine residue in the Nav1.5 I–II linker (Hund et al., 2010; Makara et al., 2014). Mouse CMs expressing a mutant form of βIV spectrin show a positive shift in INa steady-state inactivation, elimination of late INa, shortened APD, and decreased QT intervals (Hund et al., 2010), confirming that formation of the Nav1.5-ankyrin-G signaling complex is critical for maintaining normal cardiac excitability.

Table 2.

Nav1.5 ID interacting proteins.

| Interacting protein | Effects on Nav1.5 | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Ankyrin-G (AnkG) | Proper expression at plasma membrane and coupling to actin cytoskeleton | Mohler et al., 2004 |

| Calmodulin (Cal) | Regulates biophysical properties | Tan et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2004; Young and Caldwell, 2005; Gabelli et al., 2014 |

| Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKIIδ) | Phosphorylation and modulates excitability | Hund et al., 2010; Makara et al., 2014 |

| Fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 1B (FHF1B) | Modulate channel gating | Liu et al., 2003 |

| Nedd4-like-ubiqutin-protein ligases (Nedd4) | Ubiquitination and regulated internalization. Possible mechanism in modulation of channel density at the plasma membrane | Van Bemmelen et al., 2004; Rougier et al., 2005 |

| Synapse-associated protein 97 (SAP97) | Stability and anchoring to the cell membrane | Petitprez et al., 2011; Matsumoto et al., 2012 |

Cytoskeletal integrity is a pre-requisite for normal electrical coupling. During cardiac development, GJ proteins and Nav1.5 appear at the ID after formation of adherens junctions (Vreeker et al., 2014). The perinexus, a newly identified region of the ID, is defined as the area surrounding the plaque of functional GJs (Rhett et al., 2013) (Figure 3B). Here, free connexons appear at the periphery of the GJ, after which they bind to zonula occludens1 (ZO-1). GJs form when ZO-1 free connexons from one cell associate with ZO-1 free connexons of a neighboring cell (Rhett et al., 2011). Disruption of Cx43/ZO-1 interactions increases GJ size (Hunter, 2005), and in a ZO-1 null model, GJ plaques are larger (Palatinus et al., 2010). Cx43 also interacts with Nav1.5 in the perinexus (Rhett et al., 2012). The presence of Nav1.5 at the perinexus may suggest that, in addition to GJ proteins, NaVs may participate in coupling across the extracellular space, with increasing evidence supporting that both Cx43 and Nav1.5 are necessary for cell-to-cell transmission of APs (Gutstein et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2011; Jansen et al., 2012).

Nav1.5 contributes to at least two distinct multiprotein complexes in ventricular CMs, one at the lateral membrane containing dystrophin and syntrophin (Figure 2), and the other at the ID involving the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) protein adapter protein, synapse-associated protein 97 (SAP97), and ankyrin-G (Petitprez et al., 2011) (Figure 3C). In heterologous cells, surface expression of Nav1.5 is regulated by its interaction with SAP97 via a PDZ-domain (post-synaptic density protein-PSD95, disc large tumor suppressor-Dlg1, zonula occludens1-ZO1). Either the truncation of the fourth domain of Nav1.5 (Shy et al., 2014) or depletion of SAP97 (Matsumoto et al., 2012) results in reduced channel cell surface expression, with a subsequent decrease of INa.

Nav1.5 also interacts with fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 1B (FHF1B) (Liu et al., 2003), calmodulin (Kim et al., 2004; Young and Caldwell, 2005), Nedd4-like-ubiqutin-protein ligases (Van Bemmelen et al., 2004; Rougier et al., 2005), and is phosphorylated by Fyn (Ahern et al., 2005), a src family tyrosine kinase, all of which are involved in the regulation of channel subcellular localization and activity (Figure 3C). Taken together, these results accentuate the idea that cardiac NaVs associate with protein complexes that are specific to subcellular domains, and these interactions are critical to cardiac physiology. Undoubtedly, changes in one component of a given complex results in significant consequences to overall cardiac excitability and synchrony.

NaV-β subunits modulate cardiac excitability

In mammalian genomes, five NaV-β subunits are encoded by four genes, SCN1B-SCN4B (O'Malley and Isom, 2015). NaV-β1-β4 are transmembrane proteins with type 1 topology consisting of an extracellular N-terminus containing an immunoglobulin (Ig) domain, a transmembrane segment, and an intracellular C-terminus (Brackenbury and Isom, 2011) (Figure 1). NaV-β1B, a splice variant of SCN1B, contains the NaV-β1 N-terminal and Ig domains, but lacks a transmembrane domain (Kazen-Gillespie et al., 2000), resulting in a secreted protein (Patino et al., 2011) (Figure 1). NaV-β subunits can interact both covalently and non-covalently with NaV-α subunits: NaV-β1 and -β3 interact non-covalently with NaV-α via their N- and C-termini (McCormick et al., 1998; Meadows et al., 2001), while NaV-β2 and -β4 interact covalently with NaV-α via a single N-terminal cysteine located in the extracellular Ig loop (Chen et al., 2012; Gilchrist et al., 2013).

Canonically, NaV-βs are known as modulators of NaV electrophysiological properties and cell surface expression (Brackenbury and Isom, 2011). Heterologous expression systems and mouse models have shown that NaV-βs modulate NaV−αs in cell type specific manners, thus the NaV α/β subunit composition of a given cell confers unique biophysical properties that can be finely tuned (Calhoun and Isom, 2014). Not surprisingly, NaV-β1 modulation of Nav1.5 varies depending on the system studied. In Xenopus oocytes, the amplitude of Nav1.5 expressed INa increases with increasing amounts of β1 mRNA (Qu et al., 1995). Antisense-mediated post-transcriptional silencing of Scn1b in H9C2, a CM line, alters TTX-S and TTX-R Nav-α mRNA and protein expression, resulting in decreased INa (Baroni et al., 2014). In contrast, Scn1b null mouse CMs have increased expression of Scn3a and Scn5a, along with increased TTX-S and TTX-R INa (Lopez-Santiago et al., 2007). In heterologous cells, NaV-β1 expression results in slight changes in Nav1.5 INa, but significant effects on voltage-dependence and channel kinetics. In Tsa201 cells transfected with Nav1.5, co-expression of NaV-β1 positively shifts the voltage-dependence of inactivation (Malhotra et al., 2001). Co-expression of NaV-β1 with Nav1.5 in Xenopus oocytes causes a depolarizing shift in steady-state inactivation compared with WT alone (Zhu et al., 2017), suggesting that β1 may allow the α subunit voltage-sensing domains to recover more rapidly to the resting state. Thus, NaV-β1 may initiate fine-tuned acute and chronic feedback mechanisms that differentially control expression and function of NaV-αs in the heart.

Nav-β1B is expressed in fetal brain and in heart at all developmental time points. When expressed alone or in the presence of TTX-S Nav-αs in a heterologous expression system, Nav-β1B is secreted (Patino et al., 2011). Secreted Nav-β1B functions as a CAM ligand to promote signal transduction in cultured neurons (Patino et al., 2011). In contrast, NaV-β1B is retained at the cell surface when co-expressed with Nav1.5 (Patino et al., 2011) and Nav-β1B co-expression increases INa density compared to NaV1.5 alone (Watanabe et al., 2008). The disease variant, β1B-G257R (Figure 1, Table 1), causes Nav-β1B to be retained inside the cell, resulting in a functional null phenotype (Patino et al., 2011). The variant, β1B-W179X (Figure 1, Table 1), fails to increase Nav1.5 INa density, suggesting that it may also be a functional null mutation (Watanabe et al., 2008). A number of Nav-β1B variants have now been linked to cardiac arrhythmias (Figure 1, Table 1), thus this subunit is critical to cardiac physiology.

While the Nav-αs are known to form and function as monomers, recent evidence suggests that they can also form dimers, and that dimerization is mediated through an interaction site within the first intracellular loop (Clatot et al., 2017). NaV-α dimers display coupled gating properties, which are mediated through the action of 14-3-3 proteins (Clatot et al., 2017). The 14-3-3 family of proteins is important for the regulation of cardiac INa, and disrupted 14-3-3 expression may exert pro-arrhythmic effects on cardiac electrical properties (Allouis et al., 2006; Sreedhar et al., 2016). The functional importance of cardiac NaV-α dimerization may be to target and enhance the density of channels at specific subcellular domains. Nav1.5-R1432G, a surface localization defective SCN5A mutant, displays a dominant negative effect on WT Nav1.5, but only in the presence of NaV-β1 (Mercier et al., 2012). Thus, NaV-β1 may normally mediate physical interactions between Nav1.5 dimers, however further research must be performed.

NaV-βs do more than modulate INA

NaV-β subunits are multifunctional (O'Malley and Isom, 2015). In addition to modulating channel gating and cell surface expression/localization, NaV-βs are Ig superfamily cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) that facilitate cell–cell communication and initiate intracellular signaling cascades. NaV-β1 and -β2 participate in trans-homophilic cell adhesion, resulting in the recruitment of ankyrin-G to the plasma membrane at sites of cell–cell contact (Malhotra et al., 2000). Importantly, this occurs both in the presence and absence of NaV-α, at least in vitro. NaV-β1 and -β2 also participate in cell–matrix adhesion, binding tenascin-R and tenascin- C to modulate cell migration (Srinivasan et al., 1998; Xiao et al., 1999). The NaV-β3 amino acid sequence is most similar to NaV-β1 compared to the other NaV-β subunits (Morgan et al., 2000). While NaV-β3 does not function as a CAM when expressed in Drosophila S2 cells, as shown for NaV-β1 and -β2 (Chen et al., 2012), it does so in mammalian cells where trans homophilic adhesion was shown to require an intact Cys2–Cys24 disulfide bond (Yereddi et al., 2013).

NaV-β function, localization, and expression are regulated by multiple post-translational modifications including phosphorylation, glycosylation, and proteolytic cleavage (Calhoun and Isom, 2014). All NaV-βs have highly glycosylated N-terminal domains, containing 3 to 4 N-linked glycosylation sites each (Isom et al., 1992; McCormick et al., 1998; Johnson et al., 2004), and these modifications contribute to cell surface expression and channel modulation (Johnson et al., 2004). Lastly, NaV-βs are targets for sequential proteolytic cleavage by α-secretase/BACE1 and γ-secretase, resulting in the release of N-terminal and C-terminal domains (Wong et al., 2005). These cleavage products may have important physiological effects on transcriptional regulation of NaV-α subunit genes. For example, γ-secretase cleavage of NaV-β2 in neurons in vitro leads to translocation of the intracellular domain to the nucleus, where it increases SCN1A mRNA expression and Nav1.1 protein (Kim et al., 2007).

Of the five Nav-β subunits, Nav-β1 has been the most studied in terms of its CAM function. In the heart, NaV-β1 ID localization suggests a role in cardiac cell–cell contact. Scn1b and Scn5a have overlapping temporal and spatial expression profiles during heart development (Domínguez et al., 2005). In ventricular CMs, NaV-β1 is co-localized at the ID (Kaufmann et al., 2010) with Nav1.5 (Maier et al., 2004), as well as at the T-tubules with TTX-S channels (Malhotra et al., 2001; Lopez-Santiago et al., 2007). Recent evidence suggests that NaV-β1-mediated cell–cell adhesion may occur at the perinexal membrane, and this putative interaction can be acutely inhibited by βadp1, a novel peptide mimetic of the NaV-β1 CAM domain (Veeraraghavan et al., 2016). Dose-dependent administration of βadp1 decreased cellular adhesion in NaV-β1-overexpressing fibroblasts. 75% of βadp1-treated hearts exhibited spontaneous ventricular tachycardias, revealing preferential slowing of transverse conduction. These data support a role for trans NaV-β1-mediated cell–cell adhesion at the perinexal membrane and suggest a role for adhesion in conduction (Figure 3B). Because a large proportion of SCN1B disease variants affect the Ig domain (Figure 1), it is likely that disruption of NaV-β1-mediated cell–cell adhesion contributes to disease mechanisms and, if so, that restoring adhesion may be a future therapeutic target.

The NaV-β1 intracellular domain can be phosphorylated at tyrosine (Y) residue 181 (Malhotra et al., 2002, 2004; McEwen et al., 2004), possibly through activation of Fyn kinase (Brackenbury et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2014) (Figure 1). β1Y181E, a phosphomimetic, participates in cell adhesion but does not interact with ankyrin or modulate INa, suggesting that Y181 is an important regulatory point for cytoskeletal association and channel modulation (Malhotra et al., 2002). In CMs, tyrosine-phosphorylated NaV-β1 and non-phosphorylated NaV-β1 are differentially localized to subcellular domains where they interact with specific cytoskeletal and signaling proteins (Malhotra et al., 2004). At the T-tubules, non-phosphorylated NaV-β1 interacts with TTX-S NaVs and ankyrin-B (Figure 2) (Malhotra et al., 2004). In contrast, tyrosine-phosphorylated NaV-β1 is localized to the ID where it interacts with Nav1.5 and N-cadherin (Figures 3B,C) (Malhotra et al., 2004). We do not yet know whether phosphorylation targets NaV-β1 to specialized subcellular regions or whether NaV-β1 is differentially phosphorylated upon arrival. Phosphorylation may be a signaling mechanism by which cells regulate the density and localization of NaV-β1, and by association Nav-αs, to specific subcellular domains. In summary, NaV-β1 subunits serve as critical links between the extracellular and intracellular signaling environments of cells through ion channel modulation as well as cell–cell adhesion.

NaV-β1 modulates potassium channels

NaV-β1 can interact with and modulate voltage-gated potassium channels (Kvs) in addition to NaVs. Kv-α subunits assemble as tetramers that normally associate with modulatory Kv-β subunits (Snyders, 1999). The Kv4.x subfamily of channels express rapidly activating, inactivating, and recovering cardiac transient outward currents (Ito) (Snyders, 1999). Co-expression of NaV-β1 with Kv4.3 results in a ~four-fold increase in Ito density (Deschênes and Tomaselli, 2002). Additionally, NaV-β1 alters the voltage-dependence and kinetics of channel gating compared to Kv4.3 expressed alone (Deschênes and Tomaselli, 2002). Importantly, NaV-β1 associates with Kv4.2 and enhances its surface expression (Marionneau et al., 2012). Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings obtained from cells expressing Kv4.2 with NaV-β1 resulted in higher Ito densities compared to Kv4.2 alone (Marionneau et al., 2012). NaV-β1 can also interact with and modulate Kv1 (Kv1.1, Kv1.2, Kv1.3, or Kv1.6) and Kv7 (Kv7.2) channels (Nguyen et al., 2012). Lastly, NaV-β1B can also associate with Kv4.3, resulting in increased Ito (Hu et al., 2012). Thus, Kv currents can be modulated by NaV-β subunits, at least in heterologous expression systems. Transfection of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes with siRNA targeting NaV-β1 significantly reduced the expression of Kv4.x protein and reduced both INa and Ito (Deschênes et al., 2008), suggesting that NaV-β1 can modulate Kv currents in the heart in vivo.

The inward rectifier current IK1, expressed by Kir2.1, is critical for setting the resting membrane potential and modulating the late-phase of repolarization and AP duration in CMs (Nerbonne and Kass, 2005). Similar to Nav1.5, Kir2.x channels contain a C-terminal PDZ-binding domain which mediates interaction with SAP97 and syntrophin (Matamoros et al., 2016). It is thought that Kir2.x channels associate in microdomains that include caveolin 3, Nav1.5, SAP97, and syntrophin (Vaidyanathan et al., 2013). Nav1.5 interacts with α1-syntrophin via an internal N-terminal PDZ-like binding domain in addition to the C-terminal PDZ-binding domains (Matamoros et al., 2016). Importantly, Nav1.5-β1 co-expression increases Kir2.1 and Kir2.2, but not Kir2.3, currents, again suggesting that these channels are functionally linked and that Nav-β1 is critical to the formation of multi-ion channel complexes.

In vivo roles of Scn1b

Animal models have been instrumental in understanding the role of Scn1b in cardiac excitability. Scn1b deletion in mice results in severe seizures, ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden death prior to weaning (Chen, 2004). Scn1b null ventricular CMs exhibit prolonged AP repolarization, increased Scn5a/Nav1.5 gene and protein expression, increased Scn3a expression, increased transient and persistent INa density, and prolonged QT and RR intervals (Lopez-Santiago et al., 2007). In agreement with an adhesive role for β1, cytoskeletal disruption in CMs also results in increased persistent INa (Undrovinas et al., 1995). Consistent with this, ventricular CMs isolated from cardiac-specific Scn1b null mice have increased INa density, increased susceptibility to polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias, and altered intracellular calcium handling that is TTX-S (Lin et al., 2015). These data indicate that loss of Scn1b expression is arrhythmogenic, mediated by altered ion channel gene and protein expression, INa, IK, and calcium handling. Cardiac specific Scn1b deletion increases the duration of calcium signaling, resulting in delayed afterdepolarizations (Lin et al., 2015). It will be interesting to determine if expression of disease-associated SCN1B variants leads to dysfunctional ryanodine receptor signaling, which can also result in altered levels of intracellular calcium and the generation of arrhythmias (Bers, 2008; Fearnley et al., 2011; Glasscock, 2014).

The cardiac AP relies on the orchestration of multiple ion channels in concert. NaV-β1 is an important modulator of Nav-α as well as some KV- and Kir-α subunits. NaV and K channels may be functionally linked through NaV-β1/β1B, and if so, defects in this mechanism may contribute to cardiac disease. It will be critical to determine the physiological effects of NaV-β1 interaction with other K channels, calcium channels, or other calcium-handling proteins at the T-tubules. It is intriguing to consider that NaV-β1 may serve as a central communication hub between sodium, potassium, and calcium channel families to coordinate depolarization, repolarization, and calcium signaling in CMs.

SCN1B and human disease

SCN1B variants are implicated in a variety of inherited pathologies, including epileptic encephalopathy and cardiac arrhythmias (O'Malley and Isom, 2015) (Figure 1, Table 1). The epileptic encephalopathy Dravet syndrome is linked to heterozygous variants in SCN1A leading to haploinsufficiency in most patients, however, a subset of patients has SCN1B homozygous loss-of-function variants (Patino et al., 2009). The leading cause of mortality in Dravet syndrome is Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) (Nobili et al., 2011; Kalume, 2013; Devinsky et al., 2016). SCN1B variants are also linked to inherited cardiac arrhythmia syndromes that increase the risk of sudden death, including BrS (Hu et al., 2012), LQTS (Riuró et al., 2014), atrial arrhythmias (Watanabe et al., 2009), and SIDS (Hu et al., 2012). Diagnostic overlap between epilepsy and cardiac conduction disease can confound causative links between the two phenotypes (Ravindran et al., 2016). Cardiac conduction abnormalities can be poorly recognized in patients with epilepsy and vice versa (Zaidi et al., 2000). A retrospective electrocardiography study revealed that abnormal ventricular conduction was more common in SUDEP cases than in epileptic controls (Chyou et al., 2016). We propose that variants in SCN1B, including those linked to epilepsy, predispose patients to compromised cardiac electrical abnormalities. Thus, cardiovascular evaluation may be helpful in treating epileptic encephalopathy patients.

Summary

NaV-β1 and -β1B are multifunctional molecules that associate with Nav and K channels, cytoskeletal proteins, CAMs, and extracellular matrix molecules in the heart and brain. In addition, NaV-β1/β1B modulate multiple ionic currents, channel expression levels, and channel subcellular localization. Thus, it is not surprising that variants in SCN1B are linked to devastating cardiac and neurological diseases with a high risk of sudden death. In the field of cardiac physiology, important questions remain regarding specific cardiac NaV-β1 binding partners, potential effects of NaV-β1 on calcium-handling, the potential role of NaV-β1 in Nav1.5 dimerization, and the mechanism of phosphorylation events that affect NaV-β1 targeting to and association with subcellular domain specific signaling complexes at the ID, lateral membrane, and T-tubules. Understanding the functions of NaV-β1 within these protein complexes will help to elucidate underlying mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias and associated sudden death, as well as lead to the discovery of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for human disease.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was funded by NIH R37-NS-076752 to LI and by T32GM00776737 to LI on which NE is a trainee.

References

- Ahern C. A., Zhang J. F., Wookalis M. J., Horn R. (2005). Modulation of the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 by Fyn, a Src family tyrosine kinase. Circ. Res. 96, 991–998. 10.1161/01.RES.0000166324.00524.dd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allouis M., Le Bouffant F., Wilders R., Péroz D., Schott J. J., Noireaud J., et al. (2006). 14-3-3 Is a regulator of the cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.5. Circ. Res. 98, 1538–1546. 10.1161/01.RES.0000229244.97497.2c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audenaert D., Claes L., Ceulemans B., Löfgren A., Van Broeckhoven C., De Jonghe P. (2003). A deletion in SCN1B is associated with febrile seizures and early-onset absence epilepsy. Neurology 61, 854–856. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000080362.55784.1C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroni D., Picco C., Barbieri R., Moran O. (2014). Antisense-mediated post-transcriptional silencing of SCN1B gene modulates sodium channel functional expression. Biol. Cell 106, 13–29. 10.1111/boc.201300040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers D. M. (2008). Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 70, 23–49. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackenbury W. J., Davis T. H., Chen C., Slat E., Detrow M. J., Dickendesher T. L., et al. (2008). Voltage-gated Na+ channel beta1 subunit-mediated neurite outgrowth requires Fyn kinase and contributes to postnatal CNS development in vivo. J. Neurosci. 28, 3246–3256. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5446-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackenbury W. J., Isom L. L. (2011). Na+ channel β1 subunits: overachievers of the ion channel family. Front. Pharmacol. 2:53 10.3389/fphar.2011.00053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun J. D., Isom L. L. (2014). The role of non-pore-forming β subunits in physiology and pathophysiology of voltage-gated sodium channels. in voltage gated sodium channels. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 221, 51–89. 10.1007/978-3-642-41588-3_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W. A. (2000). From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron 26, 13–25. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81133-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W., Goldin A. L., Waxman S. G. (2005). International Union of Pharmacology. XLVII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated sodium channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 57, 397–409. 10.1124/pr.57.4.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. (2004). Mice lacking sodium channel 1 subunits display defects in neuronal excitability, sodium channel expression, and nodal architecture. J. Neurosci. 24, 4030–4042. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4139-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Calhoun J. D., Zhang Y., Lopez-Santiago L., Zhou N., Davis T. H., et al. (2012). Identification of the cysteine residue responsible for disulfide linkage of Na+channel α and β2 subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 39061–39069. 10.1074/jbc.M112.397646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyou J. Y., Friedman D., Cerrone M., Slater W., Guo Y., Taupin D., et al. (2016). Electrocardiographic features of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsia 57, e135–e139. 10.1111/epi.13411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatot J., Hoshi M., Wan X., Liu H., Jain A., Shinlapawittayatorn K., et al. (2017). Voltage-gated sodium channels assemble and gate as dimers. Nat. Commun. 8:2077. 10.1038/s41467-017-02262-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes I., Armoundas A. a, Jones S. P., Tomaselli G. F. (2008). Post-transcriptional gene silencing of KChIP2 and Navbeta1 in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes reveals a functional association between Na and Ito currents. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 45, 336–346. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes I., Tomaselli G. F. (2002). Modulation of Kv4.3 current by accessory subunits. FEBS Lett. 528, 183–188. 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03296-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O., Hesdorffer D. C., Thurman D. J., Lhatoo S., Richerson G. (2016). Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 15, 1075–1088. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30158-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez J. N., Navarro F., Franco D., Thompson R. P., Aránega A. E. (2005). Temporal and spatial expression pattern of beta1 sodium channel subunit during heart development. Cardiovasc. Res. 65, 842–850. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnley C. J., Llewelyn Roderick H., Bootman M. D. (2011). Calcium signaling in cardiac myocytes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3:a004242. 10.1101/cshperspect.a004242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendri-Kriaa N., Kammoun F., Salem I. H., Kifagi C., Mkaouar-Rebai E., Hsairi I., et al. (2011). New mutation c.374C>T and a putative disease-associated haplotype within SCN1B gene in Tunisian families with febrile seizures. Eur. J. Neurol. 18, 695–702. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03216.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman S. A., Desmazières A., Fricker D., Lubetzki C., Sol-Foulon N. (2016). Mechanisms of sodium channel clustering and its influence on axonal impulse conduction. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 723–735. 10.1007/s00018-015-2081-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabelli S. B., Boto A., Kuhns V. H., Bianchet M. A., Farinelli F., Aripirala S., et al. (2014). Regulation of the NaV1.5 cytoplasmic domain by calmodulin. Nat. Commun. 5:5126. 10.1038/ncomms6126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellens M. E., George A. L., Chen L. Q., Chahine M., Horn R., Barchi R. L., et al. (1992). Primary structure and functional expression of the human cardiac tetrodotoxin-insensitive voltage-dependent sodium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 554–558. 10.1073/pnas.89.2.554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist J., Das S., Van Petegem F., Bosmans F. (2013). Crystallographic insights into sodium-channel modulation by the β4 subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.U.S.A. 110, E5016–E5024. 10.1073/pnas.1314557110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasscock E. (2014). Genomic biomarkers of SUDEP in brain and heart. Epilepsy Behav. 38, 172–179. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutstein D. E., Morley G. E., Tamaddon H., Vaidya D., Schneider M. D., Chen J., et al. (2001). Conduction slowing and sudden Arrhythmic death in mice with cardiac-restricted inactivation of connexin43. Circ. Res. 88, 333–339. 10.1161/01.RES.88.3.333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B., Catterall W. A. (2012). Chapter 4 – Electrical excitability and ion channels, in Basic Neurochemistry, 8th edn, Principles of Molecular, Cellular, and Medical Neurobiology, eds Brady S. T., Siegel G. J., Albers R. W., Price D. L. (Amsterdam; Boston, MA; Heidelberg; London; New York, NY; Oxford; Paris; San Diego, CA; San Francisco, CA; Singapore; Sydney; Tokyo: Elsevier; Academic Press; ), 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Holst A. G., Saber S., Houshmand M., Zaklyazminskaya E. V., Wang Y., Jensen H. K., et al. (2012). Sodium current and potassium transient outward current genes in Brugada syndrome: screening and bioinformatics. Can. J. Cardiol. 28, 196–200. 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Barajas-Martínez H., Medeiros-Domingo A., Crotti L., Veltmann C., Schimpf R., et al. (2012). A novel rare variant in SCN1Bb linked to Brugada syndrome and SIDS by combined modulation of Nav1.5 and Kv4.3 channel currents. Heart Rhythm 9, 760–769. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hund T. J., Koval O. M., Li J., Wright P. J., Qian L., Snyder J. S., et al. (2010). A β IV -spectrin / CaMKII signaling complex is essential for membrane excitability in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3508–3519. 10.1172/JCI43621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter A. W. (2005). Zonula occludens-1 alters connexin43 gap junction size and organization by influencing channel accretion. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5686–5698. 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom L. L., De Jongh K. S., Patton D. E., Reber B. F., Offord J., Charbonneau H., et al. (1992). Primary structure and functional expression of the beta 1 subunit of the rat brain sodium channel. Science 256, 839–842. 10.1126/science.1375395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen J. A., Noorman M., Musa H., Stein M., De Jong S., Van Der Nagel R., et al. (2012). Reduced heterogeneous expression of Cx43 results in decreased Nav1.5 expression and reduced sodium current that accounts for arrhythmia vulnerability in conditional Cx43 knockout mice. Heart. Rhythm 9, 600–607. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D., Montpetit M. L., Stocker P. J., Bennett E. S. (2004). The sialic acid component of the beta1 subunit modulates voltage-gated sodium channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44303–44310. 10.1074/jbc.M408900200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalume F. (2013). Sudden unexpected death in Dravet syndrome: respiratory and other physiological dysfunctions. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 189, 324–328. 10.1016/j.resp.2013.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. G., Westenbroek R. E., Zechner C., Maass A. H., Bischoff S., Muck J., et al. (2010). Functional protein expression of multiple sodium channel alpha- and beta-subunit isoforms in neonatal cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48, 261–269. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazen-Gillespie K. a, Ragsdale D. S., D'Andrea M. R., Mattei L. N., Rogers K. E., Isom L. L. (2000). Cloning, localization, and functional expression of sodium channel beta1A subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1079–1088. 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Y., Carey B. W., Wang H., Ingano L. A. M., Binshtok A. M., Wertz M. H., et al. (2007). BACE1 regulates voltage-gated sodium channels and neuronal activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 755–764. 10.1038/ncb1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Ghosh S., Liu H., Tateyama M., Kass R. S., Pitt G. S. (2004). Calmodulin mediates Ca2+ sensitivity of sodium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45004–45012. 10.1074/jbc.M407286200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Liu N., Lu J., Zhang J., Anumonwo J. M. B., Isom L. L., et al. (2011). Subcellular heterogeneity of sodium current properties in adult cardiac ventricular myocytes. Heart. Rhythm 8, 1923–1930. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., O'Malley H., Chen C., Auerbach D., Foster M., Shekhar A., et al. (2015). Scn1b deletion leads to increased tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium current, altered intracellular calcium homeostasis and arrhythmias in murine hearts. J. Physiol. 593, 1389–1407. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.277699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Dib-Hajj S. D., Renganathan M., Cummins T. R., Waxman S. G. (2003). Modulation of the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 by fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 1B. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1029–1036. 10.1074/jbc.M207074200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Tester D. J., Hou Y., Wang W., Lv G., Ackerman M. J., et al. (2014). Is sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome in Southern China a cardiac sodium channel dysfunction disorder? Forensic Sci. Int. 236, 38–45. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Santiago L. F., Meadows L. S., Ernst S. J., Chen C., Malhotra J. D., McEwen D. P., et al. (2007). Sodium channel Scn1b null mice exhibit prolonged QT and RR intervals. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 43, 636–647. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.07.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J. S., Palygin O., Bhasin N., Hund T. J., Boyden P. A., Shibata E., et al. (2008). Voltage-gated Nav channel targeting in the heart requires an ankyrin-G-dependent cellular pathway. J. Cell Biol. 180, 173–186. 10.1083/jcb.200710107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier S. K. G., Westenbroek R. E., McCormick K. A., Curtis R., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (2004). Distinct subcellular localization of different sodium channel α and β subunits in single ventricular myocytes from mouse heart. Circulation 109, 1421–1427. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121421.61896.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier S. K. G., Westenbroek R. E., Schenkman K. A., Feigl E. O., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (2002). An unexpected role for brain-type sodium channels in coupling of cell surface depolarization to contraction in the heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 4073–4078. 10.1073/pnas.261705699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makara M. A., Curran J., Little S. C., Musa H., Polina I., Smith S. A., et al. (2014). Ankyrin-G coordinates intercalated disc signaling platform to regulate cardiac excitability in vivo. Circ. Res. 115, 929–938. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makita N., Bennett P. B., George A. L. (1994). Voltage-gated Na+ channel beta 1 subunit mRNA expressed in adult human skeletal muscle, heart, and brain is encoded by a single gene. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 7571–7578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra J. D., Chen C., Rivolta I., Abriel H., Malhotra R., Mattei L. N., et al. (2001). Characterization of sodium channel alpha- and beta-subunits in rat and mouse cardiac myocytes. Circulation 103, 1303–1310. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.9.1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra J. D., Kazen-Gillespie K., Hortsch M., Isom L. L. (2000). Sodium channel β subunits mediate homophilic cell adhesion and recruit ankyrin to points of cell-cell contact. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 11383–11388. 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra J. D., Koopmann M. C., Kazen-Gillespie K. A., Fettman N., Hortsch M., Isom L. L. (2002). Structural requirements for interaction of sodium channel beta 1 subunits with ankyrin. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 26681–26688. 10.1074/jbc.M202354200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra J. D., Thyagarajan V., Chen C., Isom L. L. (2004). Tyrosine-phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated sodium channel β1 subunits are differentially localized in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40748–40754. 10.1074/jbc.M407243200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marionneau C., Carrasquillo Y., Norris A. J., Townsend R. R., Isom L. L., Link A. J., et al. (2012). The sodium channel accessory subunit Navβ1 regulates neuronal excitability through modulation of repolarizing voltage-gated K+ channels. J. Neurosci. 32, 5716–5727. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6450-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matamoros M., Perez-Hernández M., Guerrero-Serna G., Amorós I., Barana A., Núñez M., et al. (2016). Nav1.5 N-terminal domain binding to α1-syntrophin increases membrane density of human Kir2.1, Kir2.2 and Nav1.5 channels. Cardiovasc. Res. 110, 279–290. 10.1093/cvr/cvw009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M., Fujikawa A., Suzuki R., Shimizu H., Kuboyama K., Hiyama T. Y., et al. (2012). SAP97 promotes the stability of Nax channels at the plasma membrane. FEBS Lett. 586, 3805–3812. 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick K. A., Isom L. L., Ragsdale D., Smith D., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (1998). Molecular determinants of Na+ channel function in the extracellular domain of the beta1 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3954–3962. 10.1074/jbc.273.7.3954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen D. P., Meadows L. S., Chen C., Thyagarajan V., Isom L. L. (2004). Sodium channel β1 subunit-mediated modulation of Nav1.2 currents and Cell surface density is dependent on interactions with contactin and ankyrin. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16044–16049. 10.1074/jbc.M400856200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows L., Malhotra J. D., Stetzer A., Isom L. L., Ragsdale D. S. (2001). The intracellular segment of the sodium channel beta 1 subunit is required for its efficient association with the channel alpha subunit. J. Neurochem. 76, 1871–1878. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier A., Clément R., Harnois T., Bourmeyster N., Faivre J. F., Findlay I., et al. (2012). The β1-Subunit of Nav1.5 Cardiac Sodium Channel Is Required for a Dominant Negative Effect through α-α Interaction. PLoS ONE 7:e48690 10.1371/journal.pone.0048690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler P. J., Rivolta I., Napolitano C., LeMaillet G., Lambert S., Priori S. G., et al. (2004). Nav1.5 E1053K mutation causing Brugada syndrome blocks binding to ankyrin-G and expression of Nav1.5 on the surface of cardiomyocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.U.S.A. 101, 17533–17538. 10.1073/pnas.0403711101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan K., Stevens E. B., Shah B., Cox P. J., Dixon A. K., Lee K., et al. (2000). Beta 3: an additional auxiliary subunit of the voltage-sensitive sodium channel that modulates channel gating with distinct kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2308–2313. 10.1073/pnas.030362197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M., Millican-Slater R., Forrest L. C., Brackenbury W. J. (2014). The sodium channel β1 subunit mediates outgrowth of neurite-like processes on breast cancer cells and promotes tumour growth and metastasis. Int. J. Cancer 135, 2338–2351. 10.1002/ijc.28890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne J. M., Kass R. S. (2005). Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol. Rev. 85, 1205–1253. 10.1152/physrev.00002.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer J., Rougier J.-S., Abriel H., Haas C. (in press). Functional implications of a rare variant in the sodium channel β1B subunit (SCN1B) in a five-month old male sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) case. Heart. Case Rep. 10.1016/j.hrcr.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H. M., Miyazaki H., Hoshi N., Smith B. J., Nukina N., Goldin A. L., et al. (2012). Modulation of voltage-gated K+ channels by the sodium channel β1 subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 18577–18582. 10.1073/pnas.1209142109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobili L., Proserpio P., Rubboli G. B., Montano N. C., Didato G. D., Tassinari C. (2011). Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) and sleep. Sleep Med. Rev. 15, 237–246. 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley H. A., Isom L. L. (2015). Sodium channel β subunits: emerging targets in channelopathies. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 77, 481–504. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogiwara I., Nakayama T., Yamagata T., Ohtani H., Mazaki E., Tsuchiya S., et al. (2012). A homozygous mutation of voltage-gated sodium channel beta(I) gene SCN1B in a patient with Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia 53, e200–e203. 10.1111/epi.12040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrico A., Galli L., Grosso S., Buoni S., Pianigiani R., Balestri P., et al. (2009). Mutational analysis of the SCN1A, SCN1B and GABRG2 genes in 150 Italian patients with idiopathic childhood epilepsies. Clin. Genet. 75, 579–581. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01155.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palatinus J. A., O'Quinn M. P., Barker R. J., Harris B. S., Jourdan J., Gourdie R. G. (2010). ZO-1 determines adherens and gap junction localization at intercalated disks. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 300, H583–H594. 10.1152/ajpheart.00999.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patino G. A., Brackenbury W. J., Bao Y., Lopez-Santiago L. F., O'Malley H. A., Chen C., et al. (2011). Voltage-gated Na+ channel beta1B: a secreted cell adhesion molecule involved in human epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 31, 14577–14591. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0361-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patino G. A., Claes L. R. F., Lopez-Santiago L. F., Slat E. A., Dondeti R. S. R., Chen C., et al. (2009). A functional null mutation of SCN1B in a patient with Dravet Syndrome. J. Neurosci. 29, 10764–10778. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2475-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitprez S., Zmoos A. F., Ogrodnik J., Balse E., Raad N., El-Haou S., et al. (2011). SAP97 and dystrophin macromolecular complexes determine two pools of cardiac sodium channels Nav1.5 in cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 108, 294–304. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.228312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y., Isom L. L., Westenbroek R. E., Rogers J. C., Tanada T. N., McCormick K. A., et al. (1995). Modulation of cardiac Na+ channel expression in Xenopus oocytes by beta 1 subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 25696–25701. 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan W., Patel N., Anazi S., Kentab A. Y., Bashiri F. A., Hamad M. H., et al. (2017). Confirming the recessive inheritance of SCN1B mutations in developmental epileptic encephalopathy. Clin. Genet. 92, 327–331. 10.1111/cge.12999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran K., Powell K. L., Todaro M., O'Brien T. J. (2016). The pathophysiology of cardiac dysfunction in epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 127, 19–29. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhett J. M., Jourdan J., Gourdie R. G. (2011). Connexin 43 connexon to gap junction transition is regulated by zonula occludens-1. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 1516–1528. 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhett J. M., Ongstad E. L., Jourdan J., Gourdie R. G. (2012). Cx43 associates with Nav1.5 in the cardiomyocyte perinexus. J. Membr. Biol. 245, 411–422. 10.1007/s00232-012-9465-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhett J. M., Veeraraghavan R., Poelzing S., Gourdie R. G. (2013). The perinexus: Sign-post on the path to a new model of cardiac conduction? Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 23, 222–228. 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riuró H., Campuzano O., Arbelo E., Iglesias A., Batlle M., Pérez-Villa F., et al. (2014). A missense mutation in the sodium channel β1b subunit reveals SCN1B as a susceptibility gene underlying long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 11, 1202–1209. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogart R. B., Cribbs L. L., Muglia L. K., Kephart D. D., Kaiser M. W. (1989). molecular cloning of a putative tetrodotoxin-resistant rat heart Na+ channel isoform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 8170–8174. 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougier J.-S., van Bemmelen M. X., Bruce M. C., Jespersen T., Gavillet B., Apothéloz F., et al. (2005). Molecular determinants of voltage-gated sodium channel regulation by the Nedd4/Nedd4-like proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C692–C701. 10.1152/ajpcell.00460.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satin J., Kyle J. W., Chen M., Bell P., Cribbs L. L., Fozzard H. A., et al. (1992). A mutant of TTX-resistant cardiac sodium channels with TTX-sensitive properties. Science 256, 1202–1205. 10.1126/science.256.5060.1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer I. E., Harkin L. A., Grinton B. E., Dibbens L. M., Turner S. J., Zielinski M. A., et al. (2006). Temporal lobe epilepsy and GEFS+ phenotypes associated with SCN1B mutations. Brain 130, 100–109. 10.1093/brain/awl272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shy D., Gillet L., Abriel H. (2013). Cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5 distribution in myocytes via interacting proteins: the multiple pool model. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 886–894. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shy D., Gillet L., Ogrodnik J., Albesa M., Verkerk A. O., Wolswinkel R., et al. (2014). PDZ domain-binding motif regulates cardiomyocyte compartment-specific nav1.5 channel expression and function. Circulation 130, 147–160. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyders D. J. (1999). Structure and function of cardiac potassium channels. Cardiovasc. Res. 42, 377–390. 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00071-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreedhar R., Arumugam S., Thandavarayan R. A., Giridharan V. V., Karuppagounder V., Pitchaimani V., et al. (2016). Depletion of cardiac 14-3-3η protein adversely influences pathologic cardiac remodeling during myocardial infarction after coronary artery ligation in mice. Int. J. Cardiol. 202, 146–153. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.08.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan J., Schachner M., Catterall W. a. (1998). Interaction of voltage-gated sodium channels with the extracellular matrix molecules tenascin-C and tenascin-R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15753–15757. 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H. L., Kupershmidt S., Zhang R., Stepanovic S., Roden D. M., Wilde A. A. M., et al. (2002). A calcium sensor in the sodium channel modulates cardiac excitability. Nature 415, 442–447. 10.1038/415442a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undrovinas A. I., Shander G. S., Makielski J. C. (1995). Cytoskeleton modulates gating of voltage-dependent sodium channel in heart. Am. J. Physiol. 269, H203–H214. 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.1.H203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan R., Vega A. L., Song C., Zhou Q., Tan B., Berger S., et al. (2013). The interaction of caveolin 3 protein with the potassium inward rectifier channel Kir2.1: physiology and pathology related to long QT syndrome 9 (LQT9). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 17472–17480. 10.1074/jbc.M112.435370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bemmelen M. X., Rougier J. S., Gavillet B., Apothéloz F., Daidié D., Tateyama M., et al. (2004). Cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.5 is regulated by Nedd4-2 mediated ubiquitination. Circ. Res. 95, 284–291. 10.1161/01.RES.0000136816.05109.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeraraghavan R., Hoeker G. S., Poelzing S., Gourdie R. G. (2016). Abstract 13129: Acute Inhibition of Sodium Channel Beta Subunit (β1) -mediated Adhesion is Highly Proarrhythmic. Circulation 134, A13129 LP-A13129. [Google Scholar]

- Vermij S. H., Abriel H., van Veen T. A. B. (2017). Refining the molecular organization of the cardiac intercalated disc. Cardiovasc. Res. 113, 259–275. 10.1093/cvr/cvw259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeker A., van Stuijvenberg L., Hund T. J., Mohler P. J., Nikkels P. G. J., van Veen T. A. B. (2014). Assembly of the cardiac intercalated disk during pre- and postnatal development of the human heart. PLoS ONE 9:e94722. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R. H., Wang D. W., Singh R., Scheffer I. E., George A. L., Phillips H., et al. (1998). Febrile seizures and generalized epilepsy associated with a mutation in the Na+-channel beta1 subunit gene SCN1B. Nat. Genet. 19, 366–370. 10.1038/1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H., Darbar D., Kaiser D. W., Jiramongkolchai K., Chopra S., Donahue B. S., et al. (2009). Mutations in sodium channel β1- and β2-subunits associated with atrial fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2, 268–275. 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.779181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H., Koopmann T. T., Scouarnec S., Le Y. T., Ingram C. R., Schott J., et al. (2008). Sodium channel β1 subunit mutations associated with Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction disease in humans. Structure 118, 268–275. 10.1172/JCI33891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong H. K., Sakurai T., Oyama F., Kaneko K., Wada K., Miyazaki H., et al. (2005). β subunits of voltage-gated sodium channels are novel substrates of β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme (BACE1) and γ-secretase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23009–23017. 10.1074/jbc.M414648200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z. C., Ragsdale D. S., Malhotra J. D., Mattei L. N., Braun P. E., Schachner M., et al. (1999). Tenascin-R is a functional modulator of sodium channel β subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26511–26517. 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Ogawa Y., Hedstrom K. L., Rasband M. N. (2007). βIV spectrin is recruited to axon initial segments and nodes of Ranvier by ankyrinG. J. Cell Biol. 176, 509–519. 10.1083/jcb.200610128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yereddi N. R., Cusdin F. S., Namadurai S., Packman L. C., Monie T. P., Slavny P., et al. (2013). The immunoglobulin domain of the sodium channel β3 subunit contains a surface-localized disulfide bond that is required for homophilic binding. FASEB J. 27, 568–580. 10.1096/fj.12-209445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K. A., Caldwell J. H. (2005). Modulation of skeletal and cardiac voltage-gated sodium channels by calmodulin. J. Physiol. 565, 349–370. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.081422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi A., Clough P., Cooper P., Scheepers B., Fitzpatrick A. P. (2000). Misdiagnosis of epilepsy: many seizure-like attacks have a cardiovascular cause. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 36, 181–184. 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00700-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Voelker T. L., Varga Z., Schubert A. R., Nerbonne J. M., Silva J. R. (2017). Mechanisms of noncovalent β subunit regulation of Na V channel gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 149, 813–831. 10.1085/jgp.201711802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]