Abstract

Background

Drug therapy combined with family therapy is currently the best treatment for adolescent depression. Nevertheless, family therapy requires an exploration of unresolved problems in the family system, which in practice presents certain difficulties. Previous studies have found that the perceptual differences of family function between parents and children reflect the problems in the family system.

Aims

To explore the characteristics and role of family functioning and parent-child relationship between adolescents with depressive disorder and their parents.

Methods

The general information and clinical data of the 93 adolescents with depression were collected. The Family Functioning Assessment Scale and Parent-child Relationship Scale were used to assess adolescents with depressive disorder and their parents.

Results

a) The dimensions of family functioning in adolescents with depressive disorder were more negative in communication, emotional response, emotional involvement, roles, and overall functioning than their parents. The differences were statistically significant. Parent-child relationship dimensions: the closeness and parent-child total scores were more negative compared with the parents and the differences were statistically significant. b) All dimensions of parent-child relationship and family functioning in adolescents with depression except the time spent together were negatively correlated or significantly negatively correlated. c) The results of multivariate regression analysis showed: the characteristics of family functioning, emotional involvement, emotional response, family structure, and income of the adolescents with depressive disorder mainly affected the parent-child relationship.

Conclusions

There were perceptual differences in partial family functioning and parent-child relationship between adolescents with depressive disorder and their parents. Unclear roles between family members, mutual entanglement, too much or too little emotional investment, negligence of inner feelings, parental divorce, and low average monthly family income were the main factors causing adverse parent-child relationship. These perceptual differences have a relatively good predictive effect on family problems, and can be used as an important guide for exploring the family relationship in family therapy.

Key words: depression, adolescent, family functioning, parent-child relationship, perceptual difference, triangle relationships, family treatment

Abstract

背景

药物联合家庭治疗是目前青少年抑郁障碍最佳治疗方法。然而医院心理科门诊开展家庭治疗,需要探讨家庭系统中尚未解决的问题,具有一定的技术和操作难度。在前人的研究中发现:亲子间的家庭功能感知差异反映了家庭系统中的问题。因此,本研究探讨抑郁障碍青少年患者家庭功能及亲子关系是否存在知觉差异及其特点,旨在为抑郁障碍青少年患者进行家庭治疗探寻家庭关系和问题奠定基础。

目的

探讨青少年抑郁障碍患者与父母间家庭功能及亲子关系的特点与作用。

方法

收集93 例青少年抑郁障碍患者的一般资料和临床资料,采用家庭功能评定量表及亲子关系量表对青少年抑郁障碍患者及父母进行评估。

结果

① 青少年抑郁障碍患者的家庭功能,在沟通,情感反应,情感介入,角色及总的功能较父母更消极,且差异有统计学意义。在亲子关系的亲密及亲子总分较父母更消极,差异有统计学意义。② 青少年抑郁患者的亲子关系与家庭功能除相处时间外的各维度均存在负相关及显著负相关。③ 多元回归分析结果显示:青少年抑郁障碍患者家庭功能的角色、情感介入、情感反应,家庭结构及收入影响了亲子关系。

结论

青少年抑郁障碍患者与父母对部分家庭功能及亲子关系存在感知差异,家庭成员之间角色不清,相互纠缠,情感投入过多或过少,忽视内心感受,父母离婚及家庭月均收入过少是导致亲子关系不良的主要因素。这些感知差异,对家庭问题有较好的预测作用,可以作为家庭治疗探寻家庭关系的切入点。

关键词: :抑郁障碍, 青少年, 家庭功能, 亲子关系, 知觉差异, 三角关系, 家庭治疗

1. Background

Adolescent depression is a common mental disorder that can create a heavy burden on families and society. Studies both within China and abroad have found: the increase of parent-child (family) conflict in adolescent depression, adverse parent-child interactions,[6-7] the presence of defects in family functioning in depression, the occurrence, development, outcome, and prognosis of depression were closely related to family functioning and possessed cyclical causality.[8-11] Therefore, an unhealthy family could lead to depressive disorder in family members.[6] Family therapy has its unique advantage as a kind of treatment method for adolescent depression.[1,2]

According to family therapy theory, personal psychological problems are not problems of the individual, but external manifestations of family system problems, reflecting issues that have not yet been or cannot be solved in the family system. Family problems could result in insecurity, depression, anxiety, aggressive behavior, internet addiction, conflict with classmates, and other psychological issues in children. [12]

There has been some discussion about how to quickly understand family dynamics by looking at the symptoms of a patient and how to use these as a stepping stone for further therapeutic exploration of family issues. Research by Caina Li, [3] Xiaoyi Fang, [4] Qiong Jin,[5] and others that focused on the perceptual difference of family functioning showed that the perceptual differences of family functioning between parents and children reflected the problems in family interaction. In the previous studies, the self-rating family functioning targeting the patients with depression showed [2,7,11] that perception of family functioning was more negative in patients with depressive disorder than persons without depression. However, there are few studies on the perceptual differences of family functioning and the parent-child relationship among different family members; and studies analyzing these factors in family with a depressed adolescent member are few as well.

2. Participants and methods

2.1 Participants

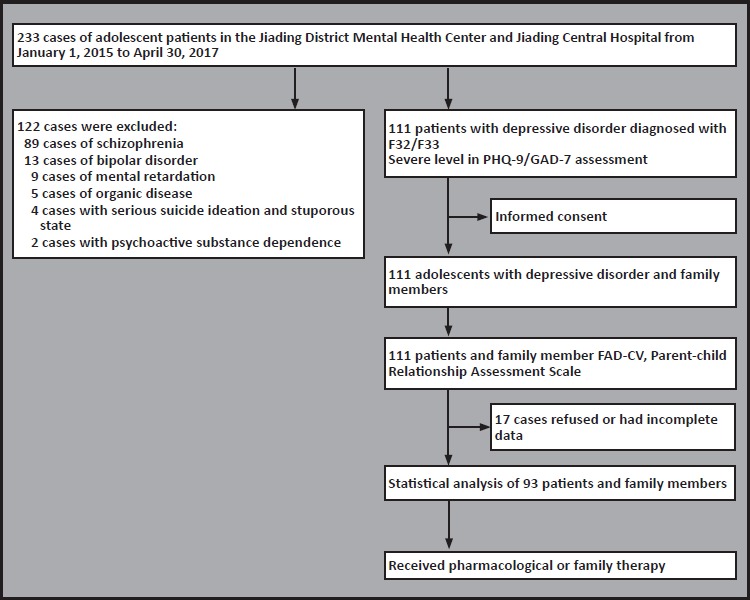

Adolescents with depressive disorder and their parents sought consultation in the Jiading District Mental Health Center and Jiading Central Hospital from January 1, 2015 to April 30, 2017. Inclusion criteria were the following: a) clinical assessment based on the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) by at least 2 trained psychiatrists with the title of attending physician or higher; meeting the diagnostic criteria for both ‘depressive episode (F32)’ or ‘recurrent depressive disorder (F33)’; the consistency Kappa value of the two raters was 0.83; b) aged 13 to 25 years (the age range for ‘adolescents’ as defined by the Department of Public Security); no gender limitation; education attainment of junior high or above; being able to complete the questionnaire independently; c) the course of disease ranged from 2 weeks to 2 years; d) informed consent from the patients and their parents; being able to cooperate with the family therapy and comply with treatment protocols. Exclusion criteria: a) organic or drug induced secondary major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder; b) having somatic or organic mental disorders; c) having serious suicidal ideation or stuporous state; d) a history of other severe mental disorders: schizophrenia, mental retardation; e) dependence or abuse of alcohol or other substances.

2.2 Study methods

2.2.1 Demographics

The contents of the General Status Questionnaire include name, gender, age, occupation, educational attainment, family structure (one-parent, two-parent, multi-generation), living arrangement (living with parents, living with multi-generations, boarding), whether or not they were an only child, parental education level, marital status, economic status (monthly income), and family history.

2.2.2 Assessment tools

The Patient Health Questionnaire Assessment-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment 7-item Scale (GAD-7) were used for assessing the severity of the disease; the Family Assessment Device (FAD-CV) was used for assessing family functioning.[13] This questionnaire was applicable for family members above 12 years old and has good reliability and validity.[14] The questionnaire included 60 entries and 7 dimensions: a) problem solving: the ability of families to solve different kinds of material and emotional problems; b) communication: the clarity of the content of the family communication and the smoothness of communication; c) division of roles: a behavior model established to meet the material and spiritual needs of family members; d) emotional response: the ability to respond to specific stimuli with appropriate emotional responses; e) emotional involvement: the degree of mutual concern and attention to the activities, hobbies, and other things of the family members; f) behavioral control: the levels of limit and tolerance of the family to its family members; g) overall functionality. Each entry had 4 options, totally agree, agree, disagree, and totally disagree. The score ranged from 1 to 4 (some entries needed reverse scoring). For each entry scoring, 1 point and 2 points represented healthy and 3 points and 4 points represented unhealthy. The average score of the entry scores included in each subscale was the final score for this subscale. If 40% of the entries in a subscale were not answered, the scale would not be scored. The higher the final score, the poorer the family functioning was, indicating that there were problems in the family system.

The Parent-child Relationship Scale was adopted to assess the parent-child relationship, [15] including the 3 dimensions of trust, intimacy, and time spent together. Each entry had 5 options, which used 5-point Likert scoring. The scoring was from 1 to 5 points. The lower the point, the less healthy the parent-child relationship was. If the total score was below 60, the parent-child relationship was considered bad; if the total score was above 60 points, the parent-child relationship was considered good. At the same time, the scale was used to evaluate the parents and took the average value of the total score. For single-parent families, only one parent was measured.

2.2.3 Assessment methods

Patients with depressive disorder and family members were recommended by senior doctors to participate in this study. The severity of their depression was measured using PHQ-9 and GAD-7. There were interviews with the family by a fixed researcher (a national level two psychologist who had received training in Li Weirong Structured Family Therapy and Zhao Xudong Systematic Family Therapy). After meeting the inclusion criteria, the Family Function Assessment Scale and Parent-Child Relationship Scale were completed independently by the patients and their parents.

2.4 Ethics

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Shanghai Jiading Mental Health Center. Informed consent was provided by all adolescent participants and their parents. This study maintained strict confidentiality for all issues involving participant’s privacy.

2.5 Data processing

All data obtained were entered into an excel form and analyzed with SPSS 17.0. Mean and standard deviation were used for describing continuous variables with a normal distribution; frequency and proportion were used to describe categorical variables. The normality test was first used to test for normal distribution when comparing the means of the 2 samples. The two-sample t-test, Person correlation analysis, and Logistic regression analysis were used.

3. Results

3.1 General demographic data of the adolescents with depressive disorder

There were a total of 93 cases (42 males, 51 females). We found no statistically significant difference between male and female patients in age, education level, course of the disease, severity of disease, and participation by their parents. See table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the age, education attainment, course of disease, and parents’ participation in different genders

| Male | Female | Statistics | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (sd) age | 16.3 (2.6) | 16.3 (2.3) | t= 1.03 | 0.63 | |

| Education attainment | |||||

| High school or above | 33 (78.6%) | 37 (72.6%) | |||

| Junior high or below | 9 (21.4%) | 14 (27.4%) | χ2= 0.449 | 0.503 | |

| Course of disease | |||||

| Initial onset | 35 (83.3%) | 41 (80.4%) | |||

| Recurrent onset | 7 (16.7%) | 10 (19.6%) | χ2= 0.133 | 0.715 | |

| Severity of the disease | |||||

| PHQ-9 | 28 (66.7%) | 27 (52.9%) | χ2= 1.796 | 0.18 | |

| GAD-7 | 22 (52.4%) | 32 (62.8%) | χ2= 1.016 | 0.313 | |

| Parental participation | |||||

| Two-parent | 38 (90.5%) | 45 (88.2%) | |||

| One-parent | 4 (9.5%) | 6 (11.8%) | χ2= 0.133 | 0.728 | |

3.2 Analysis of various dimensions of family functioning in adolescent patients with depressive disorder and their parents

Adolescent patients with depressive disorder were more negative on communication (t= 2.78, p= 0.008), emotional response (t= 4.49, p= 0.026), emotional involvement (t= 2.35, p= 0.023), role in the family (t= 2.05, p= 0.041), and the overall functioning (t= 2.40, p= 0.020) than their parents and their perceptual differences were statistically significant. Each dimension of the parent-child relationship: there were statistically significant differences in closeness (t= 3.27, p= 0.001) and parent-child total score (t= 3.28, p= 0.006). See table 2 for details.

Table 2.

Comparison of the scores of all dimensions of the family functioning and parent-child relationship between parents and children (score, x(SD))

| Variables | Adolescent group | Parents group | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Functioning Scale | ||||

| Problem solving | 12.89 (4.35) | 10.89 (3.03) | 1.79 | 0.083 |

| Communication | 14.04 (3.49) | 11.82 (2.47) | 2.78 | 0.008* |

| Emotional response | 16.43 (2.60) | 12.61 (2.10) | 4.49 | 0.036* |

| Emotional involvement | 18.89 (8.73) | 13.86 (9.17) | 2.35 | 0.023* |

| Behavioral control | 20.83 (8.58) | 17.21 (6.55) | 1.92 | 0.063 |

| Role | 21.63 (6.04) | 20.22 (3.41) | 2.05 | 0.041* |

| Overall functionality | 93.87 (14.56) | 89.99 (16.45) | 2.4 | 0.02* |

| Parent-child Relationship Scale | ||||

| Trust | 13.49 (3.12) | 14.96 (3.04) | 1.88 | 0.065 |

| Closeness | 14.85 (2.65) | 16.03 (2.97) | 3.27 | 0.001* |

| Time spent together | 12.28 (3.86) | 13.81 (3.42) | 1.7 | 0.096 |

| Parent-child total score | 47.34 (10.32) | 50.43 (10.91) | 3.87 | 0.006* |

3.3 Correlation analysis of various dimensions of the parent-child relationship and family functioning in adolescents with depressive disorder

The correlation analysis of the factors of the Family Functioning Assessment Scale and Parent-Child Relationship Scale: relevant analyses were conducted using problem solving, communication, emotional response, emotional involvement, behavioral control, role, and overall functioning in the adolescent patients with depressive disorder and the variables of trust, closeness, time spent together, and parent-child total score in the parent-child relationship. The results showed that there were negative correlations on all dimensions except for the time spent together between parent-child relationship and family functioning in adolescent patients with depressive disorder, which meant the lower the parent-child relationship score, the poorer the parent-child relationship, the higher the family function score, the worse the family functioning, and vice versa. There was significant correlation between communication, emotional response, emotional involvement, role, and the overall functioning in the family functioning and the total score of the parent-child relationship (r= -0.281, -0.362, -0373, -0.393, -0.294). Problem solving was significantly related to trust (r= -0.144) and highly related to closeness (r= -0.221). Behavioral control was significantly related to trust, closeness, and the parent-child relationship total score (r= -0.148, -0.134, -0.163). See table 3 for details.

Table 3.

The correlation of the parent-child relationship and family functioning of the adolescents with depressive disorder (r)

| Variables | Problem solving | Communication | Emotional response | Emotional involvement | Behavioral control | Role | Overall functionality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust | -0.144 | -0.202 | -0.398 | -0.205 | -0.148 | -0.337 | -0.213 |

| p | 0.042 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.039 | 0.004 | 0007 |

| Closeness | -0.221 | 0.236 | -0318 | -0.207 | -0.134 | -0.131 | -0.204 |

| p | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.040 | 0.039 | 0.008 |

| Time spent together | -0.064 | -0.058 | -0.038 | -0.057 | -0.036 | -0.043 | -0.042 |

| p | 0.078 | 0.081 | 0.094 | 0.081 | 0.094 | 0.092 | 0.092 |

| Parent-child total score | -0.13 | -0.281 | -0.362 | -0.373 | -0.163 | -0.393 | -0.294 |

| p | 0.041 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.043 | 0.003 | 0.005 |

3.4 Multivariate regression analysis of the influencing factors of the parent-child relationship in adolescents with depressive disorder

Multivariate regression analysis of the influencing factors of the parent-child relationship in adolescents with depressive disorder: taking the parent-child relationship total score of the adolescent patients with depression as the dependent variable and taking parental education level (technical secondary school and below, junior college and bachelor’s degree, master’s degree or above), family monthly income (RMB 5000 or less, RMB 5000-9999, 10000-19999 yuan, 20000 yuan or more), family structure (one-parent, two-parent, multi-generation), living mode (living with parents, living with multi-generations, boarding), whether patient was the only child or not, whether there was a family history or not, and the scores of the 7 dimensions of the Family Function Assessment Scale as the independent variables, it could be seen that family functioning, emotional involvement, emotional response, family structure, and family income (OR= 1.02, 10.278, 22.23, 0.856, 0.946) mainly affected the parent-child relationship after taking out the variables that were not significant through stepwise backward regression. See table 4 for details.

Table 4.

Multivariate regression analysis of the influencing factors of the parent-child relationship in adolescents with depressive disorder

| Item | B | SE | Wald | p | OR | 95%C.I. of exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | ||||||

| Family structure | -0.191 | 0..051 | 15.726 | 0.038 | 0.856 | 0.72 | 0.93 |

| Family income | -0.042 | 0.13 | 22.121 | 0.027 | 0.946 | 0.92 | 0.98 |

| Role | -0.302 | 0.11 | 17.33 | 0.001 | 1.02 | 1.23 | 5.62 |

| Emotional involvement | 2.517 | 0.753 | 11.39 | <0.001 | 10.278 | 4.5 | 23.48 |

| Emotional response | 2.593 | 0.583 | 21.23 | <0.001 | 22.23 | 9.82 | 25.32 |

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

a) Our study results showed that each dimension of the family functioning and parent-child relationship of the adolescent patients with depressive disorder was more negative than the parents and they had perceptual differences with their parents. These results were similar to reports on perceptual differences of family functioning between the Chinese patients with neuroses and their parents.[5] It was also in line with studies published both in China and abroad about the perceptual differences between adolescents and their parents.[3,4,16,17] Our findings highlight the unique family relationship problems that adolescents with depression face within the Chinese cultural background. In contrast, previous studies tended to explore the relationship between the parent-child conflict during adolescence instead of applying these differences to the discussion of the family relationship in the practice of clinical family therapy.

According to family therapy theory, a good parental relationship is the cornerstone of family harmony. A bad parental relationship might affect the development of teenagers, leading to a parent-child triangular relationship that seeks to stabilize parental emotion, alleviate family conflicts, and form a balanced family system. Minuchin C. (2010) pointed out that children formed the parent-child triangle relationship through the alliance with their parents and obtained the authority greater than both parents, resulting in the loss of parents’ ability to discipline their children and intensification of the parent-child conflict. Because the contradiction between parents was buffered by children’s entry, a new adverse family structure is formed. Li Weirong’s structural family therapy[18] needed to present a triangular parent-child relationship and an adverse family interaction mode in order to set the adolescents free from the parent-child triangular relationship. In order to assess the relationship between the children’s symptoms and unresolved conflicts between parents and family members using the objective data, Li captured the abnormal fluctuation of the physiological indexes of children in the paradoxical conversation and interaction when they confronted their parents through the detection of children’s skin temperature, palm sweat, heart rate, and other physiological indexes in the Shanghai “Source of Family” study. This study of children’s paradoxical reactions to their parents won the 2014 Award for Distinguished Contribution to Family Therapy Research and Practice from the American Family Therapy Academy. In terms of the perceptual difference of the adolescent patients with depressive disorder and their parents, it could be used to find the breakthrough point of the family problems from the angle of the family relationship. It could be used as objective evidence for evaluating the symptoms of the children and the unresolved conflicts between parents and family members in outpatient clinics with an absence of instruments.

b) Our study found that all dimensions except for the time spent together of the parent-child relationship and family functioning in adolescents with depressive disorder had a negative correlation or a significant negative correlation. This study does not support the idea that the time parents spend with adolescents will affect family functioning and parent-child relationship; however, this amount of time is correlated with quality of family relationship. [16,17,19] Although they are not as important as trust and closeness, the amount of time will have an impact on the quality of family relationships. We speculate that the quality of the time parents spent with their children is better than quantity. Of course, further studies are needed to verify this observation and to confirm its possible causes.

c) Our study also found that the role, emotional involvement, emotional response, family structure, and income of the family affected the parent-child relationship. Unclear roles between family members, mutual entanglement, too much or too little emotional investment, negligence of inner feelings, parental divorce, and low average monthly family income are the main factors causing adverse parent-child relationships. This result is the same as other studies. For instance, Wang and Crane (2001) found that the lower the parents’ satisfaction towards marriage, the more likely they are to feel the presence of the triangular relationship between parents and children. The study results of Cheng and colleagues (2002) shows that the children with divorced parents are more likely to form a parent-child triangle relationship with one of their parents than the children whose parents continue to stay married. Children whose parents are not divorced are more likely to experience parentification than the ones whose parents are divorced.

4.2 Limitations

This study only included adolescent patients with depressive disorder and their parents at the Shanghai Jiading District Mental Health Center and Jiading Central Hospital and there was no sample estimation.

4.3 Implications

One of the reasons for the limited use of the family therapy is that the discussion from the patients’ symptoms to the family relationship and conflicts is difficult. This topic is a private topic for the family and may automatically trigger resistance from patients and family members, making therapy more difficult. This study was the first study to explore the characteristics of family functioning and the parent-child relationship among adolescent patients with depressive disorder and their parents. It found that there were perceptual differences in partial family functioning and parent-child relationship between patients and their parents. The prediction of problems in family interactions by the perceptual difference can be used as a point of breakthrough in family therapy to explore family relationships. In addition, the adverse parent-child relationship reflects family problems. The family problems that have not been shown will be expressed through the child’s mind and body. If there are unclear roles between family members, mutual entanglement, too much or too little emotional involvement, negligence of inner feelings, single families with parental divorce, or too little family income, it could seriously affect the development of adolescents and their health.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the study

Biography

Qing Chen acquired her Master’s degree from neurology in the Hubei University of Medicine in 1993. She has been working at the Jiading Central Hospital in Shanghai since 2016. Currently she works as the director of the psychology department. Her research focuses on sleep disorders and also pharmacological and psychological treatments for depression and anxiety disorders. Her most recent research direction in mental health focuses on family therapy in a general hospital setting.

Footnotes

Funding statement

Shanghai Health and Family Planning Commission (project code: 201440601).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Informed consent

All the participants in this study provided signed informed consent before participation.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Shanghai Jiading District Mental Health Center.

Authors’ contributions

Qing Chen: head of the project

Wenyong Du: collection and diagnosis of the cases

Yan Gao: collection and coordination of the cases

Changlin Ma: collection and diagnosis of the cases

Chunxia Ban: collection and diagnosis of the cases

Fu Meng: project supervision and consultation

References

- 1.Peng J, Kong LJ, Zhu SH, Zuo XY, Zhang YP. [Study on Adolescent Depression Pathogenesis and Family Therapy]. Zhongguo Yi Xue Chuang Xin Za Zhi. 2014; 24(11): 120-122. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1 674-4985.2014.24.041 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang JK, Zhao XD. [The system views of adolescent depression and family function from]. Guo Ji Jing Shen Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2011; 38(1): 30-32. Chinese [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li CN, Zhou H. [Relationships between Perceptual Differences of Family Functioning and Adolescent Loneliness]. Xin Li Ke Xue Za Zhi. 2007; 30(4): 810-813. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1671-6981.2007.04.010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang XY, Zang JT, Xu J, Yang AL. [Adolescent-mother Discrepancies in Perceptions of Parental Conflict and Adolescent Problem Behaviors]. Xin Li Ke Xue Za Zhi. 2004; 27(1): 21-25. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1671-6981.2004.01.006 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin Q, Li XS, Ji YF, Zhou XQ, Xie W, Liu HZ, Jiang LL. [Characteristics of family functioning of neurosis patients and perceptual differences between patients and parents]. Anhui Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011; 32(5): 576-579. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1000-0399.2011.05.006 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu H. [Clinical characteristics of early adolescent depression]. Tai Shan Yi Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2016; 4(37): 405-406. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1004-7115.2016.04.015 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng HM, Lian R, Hong YJ. [The Effect of Family Function to Parent - Adolescent Conflict and its Intervention Strategies]. Huaihua Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2012; 31(12): 125-128. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1671-9743.2012.12.040 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang QY, Ye SX, Huang H, He XY. [Effect of family intervention on rehabilitation of patients with depression]. Jing Shen Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011; 24(1): 56-57. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1009-7201.2011.01.021 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Routt G, Anderson L. Adolescent aggression: Adolescent violence towards parents. J Aggress Maltreat T. 2011; 20(1): 1-19. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2011.537595 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du N, Ran MS, Liang SG, SiTu MJ, Huang Y, Mansfield AK, Keitner G. Comparison of family functioning in families of depressed patients and nonclinical control families in China using the Family Assessment Device and the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales II. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2014; 26(1): 47-56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes EK, Gullone E. Internalizing symptoms and disorders in families of adolescents: a review of family systems literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008; 28(1): 92-117. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yap MB, Jorm AF. Anthony Francis Jorm. Parental factors associated with childhood anxiety, depression, and internalizing problems: A systematic review and metaanalysis. J Affect Disord. 2015; 175(1): 424-440. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang XD, Wang XL, Ma H. [Assessment handbook of the mental health scale]. Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi. 1999; suppl: 142-152. Chinese [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luan FH, Du YS. [The application of Family Assessment Device]. Zhongguo Er Tong Bao Jian Za Zhi. 2016; 24(12): 1287-1259. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.11852/zgetbjzz2016-24-12-16 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li ZH, Ma JX, Connolly J. [Influence of friend and parental relationship on romantic experiences of adolescents in China and Canada]. Zhengzhou Da Xue Xue Bao (Yi Xue Ban). 2012; 47(4): 1287-1259. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1671-6825.2012.04.012 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lerner RM, von Eye A, Lerner JV, Lewin-Bizan S, Bowers EP. Special issue introduction: the meaning and measurement of thriving: a view of the issues. J Youth Adolesc. 2010; 39(7): 707-719. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9531-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lerner R M, Lerner JV, von Eye A, Bowers EP, Lewin-Bizan S. Individual and contextual bases of thriving in adolescence: a view of the issues. J Adolesc. 2011; 34(6): 1107. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li WR. [Family Story]. Beijing: Chinese Social Science Press; 1995. p: 15. Chinese [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazel NA, Oppenheimer CW, Technow JR, Young JF, Hankin BL. Parent relationship quality buffers against the effect of peer stressorson depressive symptoms from middle childhood to adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2014; 50(8): 2115-2123. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0037192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]