Abstract

Introduction

The importance of seminal vesicle secretion and uterine Wnt signaling for uterus preparation and embryo implantation has been described.

Materials and Methods

In this study, we evaluated the gene expression of Wnt ligands (Wnt4 and Wnt5a) and their corresponding receptors (Fzd2 and Fzd6) using qRT-PCR and active β-catenin protein levels using western blotting in the uterine tissue of female mice mated with intact and seminal vesicle-excised (SVX) males during the pre-implantation window. We evaluated the association between these factors and implantation rates and embryo spacing.

Results

mRNA expression of Wnt4 and Wnt5a and active β-catenin protein levels decreased from Day 1 to Day 4, but reached a peak on the fifth day of pregnancy. Fzd2 also reached its highest level on Day 5. Fzd6 expression showed a decreasing trend towards the day of implantation. Lack of seminal vesicle secretion decreased Wnt4 and Wnt5a expression on Days 1 and 5 and β-catenin levels on Day 5. There were almost no significant differences in expression levels of the Fzd2 and Fzd6 receptors between groups. There were positive and negative correlations, respectively, between implantation rates and embryo spacing and Wnt4, Wnt5a and active β-catenin in the control group, but such correlations were not observed in the SVX-mated mice.

Conclusions

Significant changes occurred in the expression of several Wnt signaling members and there was a significant association between Wnt signaling and embryo implantation. Seminal vesicle secretion affects Wnt signaling in mice and consequently also affects murine embryo implantation.

Key words: Wnt signaling, embryo implantation, seminal fluid, decidualization

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung Die Bedeutung von Bläschendrüsensekret und Wnt-Signale für die Vorbereitung der Gebärmutter auf die Implantation von Embryonen wurde bereits anderweitig beschrieben.

Material und Methoden Die Studie untersuchte die Genexpression der Wnt-Liganden Wnt 4 und Wnt 5a sowie deren Rezeptoren (Fzd2 und Fzd6) mithilfe von qRT-PCR und den aktiven β-Catenin-Proteinspiegel mithilfe von Westernblot im Gebärmuttergewebe von Mäusen während der Präimplantationszeit. Die Mäuseweibchen wurden mit Männchen verpaart, die entweder über intakte Samendrüsen verfügten oder die zuvor einer Exzision der Samendrüse (SVX) unterzogen worden waren. Die Assoziationen zwischen diesen Faktoren und den Implantationsraten bzw. dem Abstand zwischen den Embryonen wurde untersucht.

Ergebnisse Der mRNA-Expression von Wnt4 und Wnt5a und der aktive β-Catenin-Proteinspiegel sanken zwischen dem 1. und dem 4. Tag nach der Verpaarung, sie erreichten aber einen Spitzenweg am 5. Tag der Schwangerschaft. Die Expression von Fzd2 erreichte ebenfalls am 5. Tag ihren Höhepunkt. Hingegen zeigte die Expression von Fzd6 eine rückläufige Tendenz bis zum Tage der Implantation. Das Fehlen von Samenblasensekret führte zu einem Rückgang von Wnt4- und Wnt5a-Expression am 1. und 5. Tag und des β-Catenin-Spiegels am 5. Tag. Es gab keine signifikanten Unterschiede zwischen den beiden Gruppen hinsichtlich der Expression der Fzd2- und Fzd6-Rezeptoren. Es bestand jeweils eine positive bzw. negative Korrelation zwischen den Implantationsraten und den Abständen zwischen den Embryos und dem Wnt4-, Wnt5a- und β-Catenin-Spiegel in der Kontrollgruppe, aber diese Korrelation fand sich nicht bei den SVX-verpaarten Mäuseweibchen.

Schlussfolgerungen Die Expression verschiedener Wnt-Liganden hat sich signifikant verändert, und es gab ebenfalls eine signifikante Assoziation zwischen dem Wnt-Signalweg und der Implantation von Mäuseembryonen. Das Vorhandensein bzw. Fehlen von Samendrüsensekret beeinflusst den Wnt-Signalweg in Mäuseweibchen und wirkt sich daher auch auf die Implantation von Mäuseembryonen aus.

Schlüsselwörter: Wnt-Signalwege, Embryoimplantation, Samenblasenflüssigkeit, Dezidualisierung

Introduction

Successful embryo implantation is dependent on the timely establishment of uterine receptivity to prepare for maternal-embryo crosstalk 1 . This preparation occurs during the short period of time referred to as the pre-implantation window which is associated with a sequential alteration of various signaling pathways as well as with uterine cell proliferation and differentiation 2 , 3 .

The Wingless-type (Wnt) family in mammals consists of at least 19 ligands that bind to 10 transmembrane Frizzled receptors (Fzd) and two low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins (LRPs) and can trigger two signaling pathways, known as the canonical and the noncanonical pathways. In the canonical pathway, the interaction of the ligands with the receptors leads to an accumulation of non-phosphorylated and sustained β-catenin (active β-catenin) in the cytoplasm that can translocate to the nucleus and induce expression of Wnt target genes. In the noncanonical pathway, the active β-catenin does not play a role (unlike the previous signaling), and activating of the receptors leads to intracellular Ca 2+ or planar cell polarity regulation (reviewed in Ref. 4 ). Wnt is involved in various physiological phenomena such as embryo development, tissue homeostasis, cell-cell adhesion, cellular division, proliferation, differentiation, invasion and migration 5 , 6 . Wnt signaling has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in the female reproductive system, especially with regard to embryo-uterine crosstalk, implantation, and decidualization 7 , 8 . In terms of implantation, it has been postulated that the Wnt signaling pathway might be regulating the circular smooth muscle of the uterus and activates implantation sites 9 . Supporting this hypothesis, increased Wnt signaling has been reported in human and mouse uteri 10 . Moreover, studies in mice with β-catenin-negative uteri have shown that this pathway is essential for implantation and pregnancy 11 .

The expression of several Wnt ligands and their Frizzled receptors in the mouse uterus during estrus as well as in early pregnancy has been documented 10 , 12 . However, attention has focused more on Wnt4 and Wnt5a because of their possibly important roles in implantation and decidualization 8 . Wnt4 can act either in canonical or noncanonical ways and ablation of this ligand in the mouse uterus could negatively affect implantation and decidualization 7 . Fzd6 is one of the main receptors for Wnt4 and previous studies revealed that Wnt4/Fzd6 interaction can signal in canonical and noncanonical ways 13 , 14 . Interestingly, Fzd6 expression has been detected in mice uteri during implantation 12 . It has been documented that Wnt4 regulates embryo implantation in mice 15 , possibly through the canonical pathway rather than through noncanonical signaling 16 . Wnt5a, another important Wnt ligand in female reproduction, has been also detected in the uterus during pregnancy and on the corresponding day of the estrous cycle 17 . Wnt5a is well-known for its noncanonical activity 18 and Fzd2 acts as the main receptor for this ligand 19 . Wnt5a and its receptor are expressed in both epithelial and stromal cells of uterine tissue 20 , and it has been suggested that this ligand is involved in embryo homing and implantation as well as decidualization 21 . Wnt5a has also been proposed as a mediator for progesterone in endometrium stromal cells 22 .

Seminal plasma (SP) is produced by several glands, but the seminal vesicles are responsible for the production of most of the fluid. Previous studies have demonstrated the supportive effect of SP on embryo implantation and pregnancy and, most interestingly, it has been shown that secretions of the seminal vesicles play the main role in this process 23 . In this context, a reduction of mating-induced tolerance for paternal alloantigens has been documented following seminal vesicle excision 24 , 25 . In mice, it has been demonstrated that seminal vesicle excision can reduce fertility 23 . Findings showed that SP could affect the immune system as well as the signaling pathways of various cells lining the female reproductive system 26 , 27 . The existence of pro-inflammatory cytokines, interleukins (ILs) and interferons (IFNs) in SP secreted by male accessory sex glands such as seminal vesicles has been shown 28 . Moreover, an inflammatory response in uterine tissue following contact with semen has also been demonstrated 29 . On the other hand, many studies have reported an activation of Wnt pathways by pro-inflammatory factors even in the endometrium 30 , 31 , 32 . One of the factors most abundantly present in SP that can potentially affect Wnt signaling in the uterus is TGF-β. It has also been suggested that this component is the most effective factor in SP and that it is involved in triggering of the maternal immune system and inflammation 33 . Other factors in SP that can potentially alter maternal Wnt signaling are IL-7 and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) 30 , 34 , 35 .

Given the abovementioned findings on the possible effect of seminal vesicle secretion on Wnt signaling pathways and because less is known about day-to-day changes in Wnt signaling during the pre-implantation window and their association with implantation, this study aimed to investigate two important Wnt ligands (Wnt4 and Wnt5a) and their corresponding receptors (Fzd2 and Fzd6) as well as active β-catenin levels in the uterine tissue of female mice mated with intact and seminal vesicle-excised (SVX) males during the pre-implantation window. The association between these factors and implantation rates and embryo spacing in mice was also investigated.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Samples were collected from 48 female adult albino NMRI mice at the age of eight weeks (mean weight: 20.5 ± 3.4 g) purchased from the RAZI Institute of Iran, of the same type also used in our previous study 36 . SVX male mice were prepared as described in our previous study 27 . During the experiments, all mice were kept in an animal lab at a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C with 60 – 70% humidity and in 12 : 12 h light-dark cycles. Animals were fed standard chow (RAZI Institute, Iran) and provided with water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (permit number: 5/46139). Three weeks after the operations on male mice, the female mice were randomly divided into two groups as follows:

mice mated with intact male mice (control group, n = 24),

mice mated with SVX male mice (SVX-mated, n = 24).

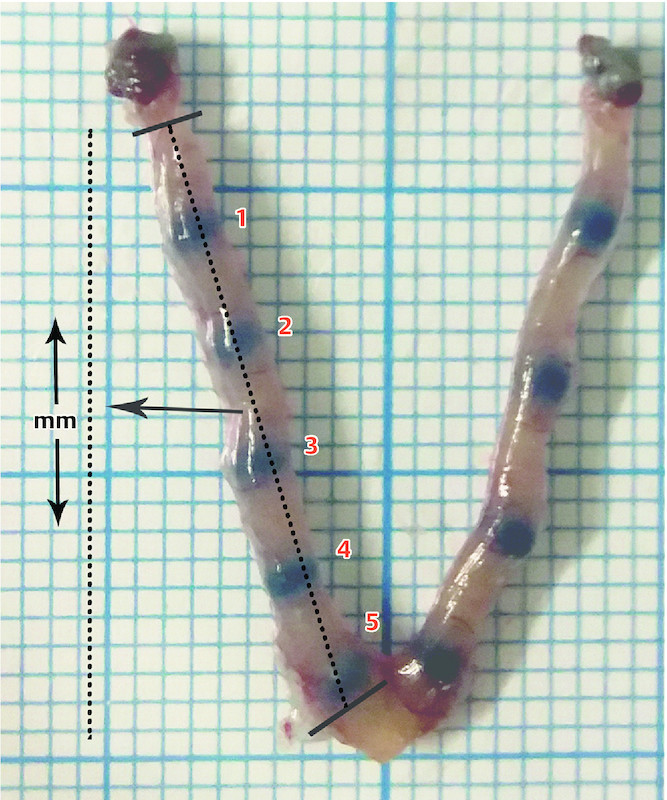

Natural mating was induced by caging three female mice with one intact or one SVX male mouse, according to the selected group. The existence of a vaginal plug or spermatozoa in the vaginal smear the next morning was considered as the first day of pregnancy. Four pregnant mice from each group were sacrificed on each day of pregnancy from Day 1 to 4, and 8 mice from each group were sacrificed on Day 5 to increase the statistical power of the implantation rate evaluation. Implantation sites on Day 5 of pregnancy were determined by injecting 0.1 ml of 1% Chicago blue (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) in saline via a tail vein as described by Deb et al. 37 . The implantation rates and the spacing between embryos were calculated. The number of implantation sites per uterus was considered to be the implantation rate. To evaluate spacing, each uterus was stretched evenly on a plate placed on 1 mm graph paper and photographed. As shown in Fig. 1 , the distance (millimeters) between ovary and cervix was calculated for each uterus horn and the space between embryos was expressed as a ratio of the number of implantation sites (n)/uterus horn length (mm). The mean distance of the embryos in the two horns was calculated for each uterus. The surgically isolated uterus was washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and stored at − 80 °C for further evaluation. The whole uterus was used for qRT-PCR and western blot analysis. To do this, a suspension of the whole uterus was prepared, and the suspension was then apportioned for molecular analysis.

Fig. 1.

Embryo implantation sites on the uterine horns of mouse uterus stained with Chicago blue. The red numbers indicate implantation. The space between embryos is expressed as the ratio of the number of implantation sites (n)/uterus horn length (mm).

Gene expression analysis

After isolation of total RNA (miRCURY ™ RNA Isolation Kit, Exiqon, Denmark), its concentration and quality were evaluated. DNase I was used to remove genomic DNA contamination. The corresponding cDNA was synthesized using the NG dART RT kit (Eurex, Poland) and the expression of Wnt4, Wnt5a, Fzd2, Fzd6, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, housekeeping gene) genes was evaluated using the MIC real-time PCR detection system (BioMolecular Systems, Australia) and the SYBR Green Kit (Eurex, Poland). For this, primers for each gene were used as follows: Wnt4: forward, GGCCATCTTGACACACATGCG, reverse, ACGCCAGCACGTCTTTACCTC; Wnt5a: forward, GTACCAGTTCCGGCATCGGAG, reverse, GCATCACCCTGCCAAAGACAG; Fzd2: forward, GCTTAAAGGAGTTGGGAGTT, reverse, GCGAGGAGAAAGGGAAATAA; Fzd6: forward, CCAAGTGAAGGAAGGGTAAG, reverse, GAGTGAACAGGCAGAGATG; GAPDH: forward, GCGACTTCAACAGCAACTC, reverse, GCCGTATTCATTGTCATACCAG. Triplicate real-time PCR assays were conducted in a final reaction volume of 12.5 µl with the following PCR program: 10 minutes of initial denaturation at 95 °C, followed by up to 40 cycles of 10 seconds at 95 °C for denaturation, 20 seconds at an optimized annealing temperature, and 20 seconds at 72 °C as the extension temperature. Because of the approximately equal amplification efficiencies in the target and reference genes, we used the 2 -ΔΔCT calculation method to calculate relative quantities 38 .

Western blot analysis

We used ice-cold RIPA buffer (Sigma–Aldrich, USA) containing protease inhibitors (cOmplete ™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Roche, Germany) to isolate proteins. The protein concentration of each sample was analyzed using a commercial kit (Pierce TM BCA protein assay kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and the sample was then prepared for loading in electrophoresis gel by mixing with a loading buffer (1 : 1 v/v) and heating for five minutes. Samples with equal concentrations of protein (50 mg/lane) were electrophoresed in 10% w/v sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The samples were then transferred to a methanol-preactivated polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Roche, Germany) and blocking was done for 60 minutes using a solution of 3% w/v dried non-fat milk in TBS plus 0.1% Tween-20. Non-phospho (active) β-catenin antibody (D13A1, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) was applied to the membrane with overnight incubation after appropriate dilution. The membrane was then washed in phosphate buffered saline Tween-20 (PBST) and incubated for one hour at 4 °C with a secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase, A6154, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). After washing 3 times, Clarity ™ Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad, USA) was then used to visualize the bands on the membrane. A commercial molecular weight marker (Thermo Scientific ™ , USA) was also used to identify the protein bands. Using the Image J software package, the density of each band was determined, and the relative density of each target protein was calculated to β-actin.

Statistical analysis

Normal distribution of the data was confirmed by skewness and kurtosis tests. Leveneʼs test was used to confirm homoscedasticity of the variances. Two-way ANOVA was used to compare quantitative data among various days of pregnancy and groups as well as the groups/days interaction. Pearsonʼs correlation test was used to detect possible correlations between study factors and implantation rates or embryo spacing. p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. SPSS V.16 software was used for statistical analysis.

Results

mRNA expression of Wnt signaling factors during pre-implantation window

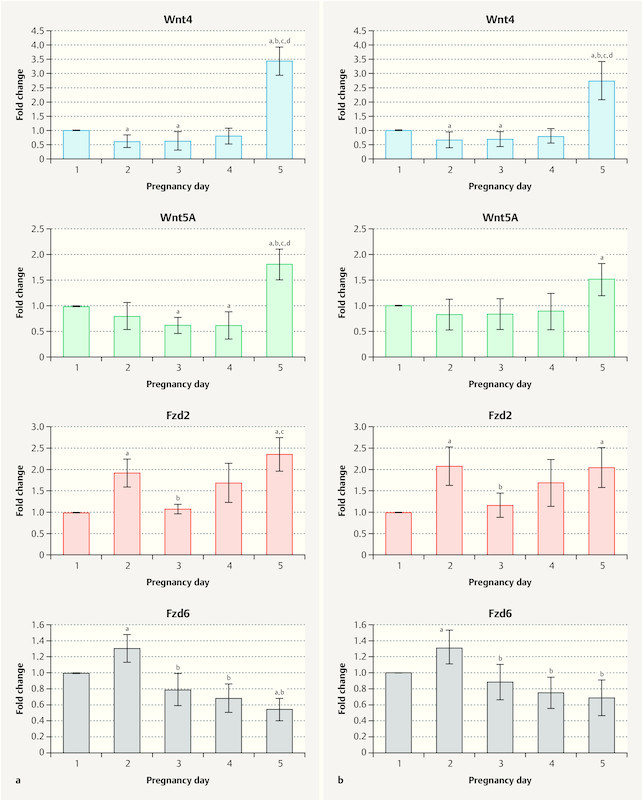

The mRNA expression of Wnt signaling factors in the uteri of control and SVX-mated mice during the pre-implantation window is shown in Fig. 2 a and b , respectively. Our results show that the expression pattern for Wnt4 was similar in both groups with expression higher on Day 1 compared to Days 2 and 3 of pregnancy (p < 0.05), and expression increasing again from the fourth day and reaching its peak on the fifth day of pregnancy. The expression of Wnt5a in the control group changed similarly, with a decrease from Day 1 to Day 4 followed by a sudden increase on Day 5 of pregnancy. In the SVX-mated group, we did not observe a significant reduction in the expression of Wnt5a from Day 1 to Day 4 of pregnancy (p > 0.05), while on Day 5, expression was significantly higher than on Day 1 (p < 0.05). The expression of Fzd2 increased significantly from Day 1 to 2 of pregnancy in both groups and then decreased on Day 3 of pregnancy, with Fzd2 expression on this day significantly lower than on the second day of pregnancy (p < 0.05). However, gene expression increased again and reached its highest level on Day 5 of pregnancy. Fzd6 expression also peaked on the second day of pregnancy in both groups, and on this day, expression was higher compared to other pre-implantation days. However, the gene expression level showed a decreasing trend from Day 3 to Day 5.

Fig. 2.

Relative mRNA expression of Wnt signaling factors in uterine tissue. The mRNA expression of Wnt4, Wnt5a, Fzd2, and Fzd6 are shown in a controls and b seminal vesicle excised (SVX)-mated mice during the embryo pre-implantation period (Days 1 to 5). Four samples from each group were examined each day, and qRT-PCR reactions were carried out three times; significant difference (p < 0.05) compared with a Day 1, b Day 2, c Day 3, and d Day 4.

mRNA expression of Wnt signaling factors in SVX-mated group compared to controls

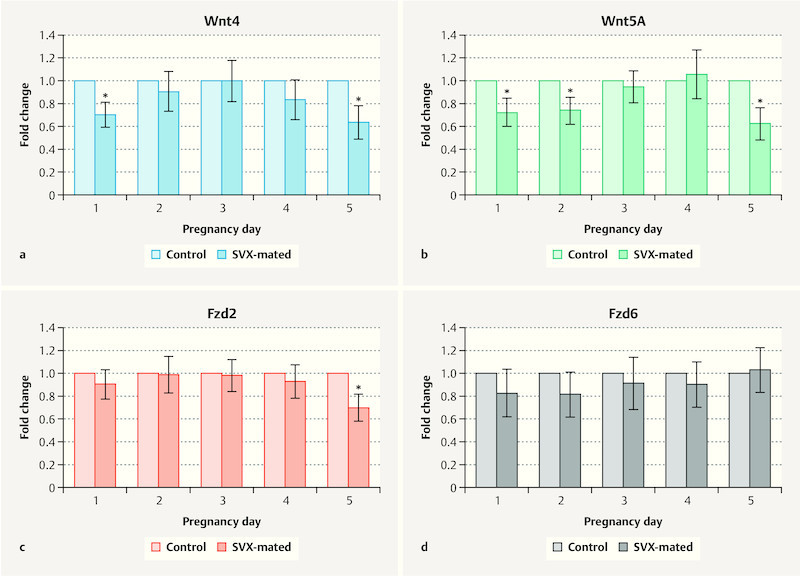

Wnt4 expression on Days 1 and 5 of pregnancy was significantly higher in controls compared to the SVX-mated group ( Fig. 3 a ). Wnt5a expression levels on Days 1, 2 and 5 of pregnancy were also higher in control mice compared with the SVX-mated group ( Fig. 3 b ). The expression levels of the receptors (Fzd2 and Fzd6) did not show a significant difference between groups during the pre-implantation window ( Fig. 3 c and d ) and only on the fifth day did we find a statistically lower expression of Fzd2 in SVX-mated mice compared to the control group ( Fig. 3 c ).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of Wnt signaling factor expression between controls and seminal vesicle excised (SVX)-mated groups. mRNA expression of a Wnt4, b Wnt5a, c Fzd2, and d Fzd6 was compared between controls and seminal vesicle excised (SVX)-mated groups during the window of pre-implantation. Four samples were examined on each day in each group and qRT-PCR evaluation was done three times.

Active β-catenin levels during pre-implantation window

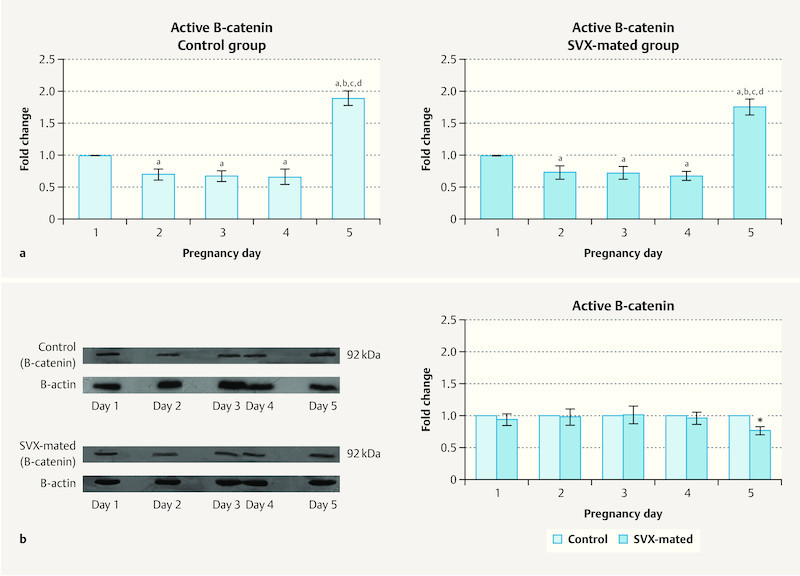

Protein levels of active β-catenin in the uterus of the mice were evaluated during the window of pre-implantation and the results are presented in Fig. 4 a and b . In both studied groups, the levels of this protein were higher on Day 1 in compared with Days 2, 3 and 4 of pregnancy. However, on the fifth day of pregnancy, protein levels reached their highest level during the pre-implantation period ( Fig. 4 a ). The protein levels of active β-catenin did not differ significantly between controls and SVX-mated groups on Days 1 to 4 of pregnancy and we only found statistically higher levels of the protein in the control group compared with SVX-mated mice on the fifth day of pregnancy (p < 0.05, Fig. 4 b ).

Fig. 4.

Active β-catenin levels during the pre-implantation window. The protein levels of active β-catenin were compared a between the pre-implantation days and b between controls and seminal vesicle excised (SVX)-mated groups. Four samples were evaluated on each day in each group and the measurement was done three times; significant difference (p < 0.05) in comparison with a Day 1, b Day 2, c Day 3, and d Day 4.

Association between Wnt signaling factors

Possible correlations between Wnt signaling factors during the pre-implantation period were investigated (results are shown in Table 1 ). Wnt4 and Wnt5a demonstrated significant positive correlations with each other and all other Wnt signaling factors on the first, second and third days of pregnancy (p < 0.05), except for Fzd2 on Days 2 and 3 of pregnancy (p > 0.05). On Day 4, Wnt4 was significantly correlated with Fzd6 and active β-catenin. There was a positive correlation between Wnt4 and active β-catenin (r = 0.960 and p < 0.001) and a negative correlation between Wnt5a and Fzd2 (r = − 0.725 and p = 0.045) on Day 5 of pregnancy. Active β-catenin was significantly correlated with Fzd2 on Days 1 and 2 and with Fzd6 on Days 1 to 4 of pregnancy ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 Correlation between Wnt signaling factors in the uteri of mice during the pre-implantation window.

| Wnt4 | Wnt5a | Fzd2 | Fzd6 | Active β-catenin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | R | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | ||

| r, correlation coefficient; p, probability | |||||||||||

| Day 1 | Wnt4 | – | – | 0.946 | < 0.001 | 0.775 | 0.024 | 0.909 | 0.002 | 0.910 | 0.002 |

| Wnt5a | 0.946 | < 0.001 | – | – | 0.751 | 0.032 | 0.871 | 0.005 | 0.966 | < 0.001 | |

| Fzd2 | 0.775 | 0.024 | 0.751 | 0.032 | – | – | 0.956 | < 0.001 | 0.766 | 0.027 | |

| Fzd6 | 0.909 | 0.002 | 0.871 | 0.005 | 0.956 | < 0.001 | – | – | 0.847 | 0.008 | |

| Active β-catenin | 0.910 | 0.002 | 0.966 | < 0.001 | 0.766 | 0.027 | 0.847 | 0.008 | – | – | |

| Day 2 | Wnt4 | – | – | 0.933 | 0.001 | 0.549 | 0.159 | 0.860 | 0.006 | 0.911 | 0.002 |

| Wnt5a | 0.933 | 0.001 | – | – | 0.747 | 0.043 | 0.924 | 0.001 | 0.821 | 0.013 | |

| Fzd2 | 0.549 | 0.159 | 0.747 | 0.043 | – | – | 0.900 | 0.016 | 0.710 | 0.045 | |

| Fzd6 | 0.860 | 0.006 | 0.924 | 0.001 | 0.900 | 0.016 | – | – | 0.779 | 0.023 | |

| Active β-catenin | 0.911 | 0.002 | 0.821 | 0.013 | 0.710 | 0.045 | 0.779 | 0.023 | – | – | |

| Day 3 | Wnt4 | – | – | 0.861 | 0.006 | − 0.104 | 0.807 | 0.949 | < 0.001 | 0.860 | 0.006 |

| Wnt5a | 0.861 | 0.006 | – | – | − 0.363 | 0.377 | 0.949 | < 0.001 | 0.892 | 0.003 | |

| Fzd2 | − 0.104 | 0.807 | − 0.363 | 0.377 | – | – | − 0.174 | 0.681 | − 0.441 | 0.274 | |

| Fzd6 | 0.949 | < 0.001 | 0.949 | < 0.001 | − 0.174 | 0.681 | – | – | 0.873 | 0.005 | |

| Active β-catenin | 0.860 | 0.006 | 0.892 | 0.003 | − 0.441 | 0.274 | 0.873 | 0.005 | – | – | |

| Day 4 | Wnt4 | – | – | 0.122 | 0.774 | 0.027 | 0.949 | 0.934 | 0.001 | 0.894 | 0.003 |

| Wnt5a | 0.122 | 0.774 | – | – | 0.357 | 0.385 | 0.146 | 0.730 | 0.020 | 0.962 | |

| Fzd2 | 0.027 | 0.949 | 0.357 | 0.385 | – | – | 0.148 | 0.726 | 0.347 | 0.399 | |

| Fzd6 | 0.934 | 0.001 | 0.146 | 0.730 | 0.148 | 0.726 | – | – | 0.802 | 0.017 | |

| Active β-catenin | 0.894 | 0.003 | 0.020 | 0.962 | 0.347 | 0.399 | 0.802 | 0.027 | – | – | |

| Day 5 | Wnt4 | – | – | 0.607 | 0.101 | 0.207 | 0.623 | 0.689 | 0.059 | 0.960 | < 0.001 |

| Wnt5a | 0.607 | 0.101 | – | – | − 0.725 | 0.045 | 0.693 | 0.057 | 0.560 | 0.102 | |

| Fzd2 | 0.207 | 0.623 | − 0.725 | 0.045 | – | – | − 0.449 | 0.265 | 0.134 | 0.752 | |

| Fzd6 | 0.689 | 0.059 | 0.693 | 0.057 | − 0.449 | 0.265 | – | – | 0.718 | 0.054 | |

| Active β-catenin | 0.960 | < 0.001 | 0.560 | 0.102 | − 0.134 | 0.752 | 0.718 | 0.054 | – | – | |

Correlation between Wnt signaling factors and implantation

As shown in Table 2 , there were positive and negative correlations between implantation rates and embryo spacing with Wnt4, Wnt5a and active β-catenin in the control group, but these correlations were not observed in the SVX-mated mice.

Table 2 Correlation of implantation rate and the spacing between implantation sites with Wnt signaling factors in uterine tissue on the day of embryo implantation (Day 5 of pregnancy) in controls and seminal vesicle excised (SVX)-mated groups.

| Implantation rate | Spacing between implantation sites | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group n = 8 |

SVX-mated group n = 8 |

Control group n = 8 |

SVX-mated group n = 8 |

|||||

| r | p | r | p | R | p | r | p | |

| r, correlation coefficient; p, probability | ||||||||

| Wnt4 | 0.966 | 0.034 | 0.821 | 0.179 | − 0.953 | 0.047 | − 0.876 | 0.124 |

| Wnt5a | 0.983 | 0.017 | 0.654 | 0.346 | − 0.967 | 0.033 | − 0.681 | 0.319 |

| Fzd2 | − 0.786 | 0.140 | − 0.791 | 0.098 | 0.805 | 0.055 | 0.795 | 0.075 |

| Fzd6 | 0.694 | 0.086 | 0.866 | 0.134 | − 0.799 | 0.071 | − 0.912 | 0.088 |

| Active β-catenin | 0.972 | 0.028 | 0.778 | 0.222 | − 0.992 | 0.008 | − 0.834 | 0.166 |

Discussion

Given the importance of Wnt signaling in early pregnancy and its association with embryo implantation, we evaluated day-to-day changes in Wnt4, Wnt5a, Fzd2, Fzd6 and active β-catenin in the uterus of normal- and SVX-mated mice.

Our results showed a higher expression of Wnt4 on the first day compared with Days 2 and 3 of pregnancy which could be due to the effects of estrogen and inflammation. In support of this hypothesis, it is well known that after mating (Day 1 of pregnancy) the mouse uterus is influenced by pre-ovulatory estrogen 39 but hormone levels then decrease on the second and third days of pregnancy 40 . However, previous studies have shown the stimulating effect of estrogen on Wnt4 expression 41 . Moreover, it has been reported that the injection of estrogen can strongly induce Wnt4 expression in rat 42 and mice 41 uteri. Hou et al. 20 found that estrogen rapidly increased Wnt4 expression and maintained it over a period of 6 hours after the hormone injection, which could explain the decrease in Wnt4 expression after the first day of pregnancy observed in our study. Another explanation for the relatively higher gene expression of Wnt4 on Day 1 compared with Days 2 and 3 could be an inflammatory response following mating. It has been reported that semen deposition during mating can induce inflammation in the female reproductive tract 29 , and activation of Wnt/catenin signaling following inflammation has been documented 32 . In mice, where semen comes directly into contact with the uterus, such an inflammatory response is likely to be more severe 43 . We found that Wnt4 expression was significantly lower in SVX-mated mice compared to the control group on Day 1 of pregnancy. As seminal vesicle secretions contain different inflammatory factors such as TNF-α 44 and given the stimulatory effect of these factors on Wnt signaling 32 , it could be postulated that a lack of seminal vesicles led to weak post-mating inflammatory response and consequently lower levels of Wnt4 expression compared to normally mated mice. The significantly higher expression of Wnt4 on Day 5 compared to other pre-implantation days indicates the important role of this factor in embryo implantation and decidualization. The essential role of Wnt4 in decidualization 7 , 45 and implantation failure following Wnt4 knockout 7 has been reported. Our results showing positive and negative correlations between Wnt4 expression and implantation rates and spacing between embryos, respectively, has confirmed the findings of previous studies. In the present study, on Day 5 of pregnancy, Wnt4 expression levels were significantly lower in the SVX-mated group than in the control mice. Since Wnt4 expression is limited to implantation and not to non-implantation sites 12 , such a reduction in expression could be due to the lower number of implantation sites in SVX-mated mice compared with the normally mated group. However, it could be also hypothesized that the lack of seminal vesicles disturbs implantation-related signaling including Wnt4 and so causes implantation failure and consequently low numbers of implantation sites. The lack of positive correlation between implantation rate and Wnt4 expression respectively in normally and SVX-mated mice also indicates dysregulation of the implantation process in the uterus in the absence of seminal vesicle secretions. However further studies are needed to find the exact reason for the reduction in Wnt4 expression in SVX-mated mice.

We evaluated Fzd6 expression as one of the main receptors for Wnt4 14 . Our results showed increased expression of the receptor on Day 2 of pregnancy compared to the other days. Given the inhibitory effect of estrogen on Fzd6 expression in mouse uteri 12 , such a peak in expression levels on Day 2 could be due to the reduction of estrogen levels and the elimination of its inhibitory effect. The lower expression of Fzd6 in mouse uteri on Days 4 and 5 of pregnancy compared to Day 1 has been reported previously 12 . We also observed a decreasing trend in the expression of this gene from Days 2 to 5 of pregnancy that suggests that this receptor may be less important for embryo implantation. The lack of positive correlation between implantation rates and Fzd6 expression levels in our study and the lack of a significant difference in the expression of this gene between implantation and non-implantation sites reported by Hayashi et al. 12 could confirm this hypothesis. We found positive correlations between the expression levels of Wnt4 and Fzd6 as well as between Fzd6 and active β-catenin on Days 1 to 4 of pregnancy, but these correlations did not occur on the fifth day. This indicates a role for the Wnt4/Fzd6/β-catenin signaling pathway during the pre-implantation window from Days 1 to 4. On the fifth day, there was no correlation between Fzd6 and Wnt4 and β-catenin, which raises the possibility that other Wnt4 receptors may be involved or Wnt4-mediated noncanonical signaling may be activated.

In the present study, uterine levels of active β-catenin during pre-implantation were similar to the expression levels of Wnt4. Because of the positive correlation between Wnt4 and active β-catenin, it could be hypothesized that active β-catenin is regulated by Wnt4 during early mouse pregnancy; further studies using Wnt4 agonist and antagonist and female mice with conditional Wnt4 knockout are required to clarify such a regulatory mechanism. We found significantly higher levels of active β-catenin on Day 5 of pregnancy compared to other pre-implantation days, which indicates the important role of this factor in embryo implantation. The peak on the day of implantation could be because of

the inductive influence of Wnt4, which is one of the potent ligands in Wnt/catenin signaling,

the stimulatory effect of progesterone on the accumulation of β-catenin in uterine stromal cells reported by Rider et al. 42 , and

the induction of β-catenin following embryo implantation, as we found a positive correlation between implantation rates and active β-catenin levels, and it has also been documented that the presence of active blastocysts could transiently and strictly induce uterine Wnt/β-catenin signaling 46 .

In accordance with our findings, the importance of β-catenin for cell–cell connection, epithelial polarity, cell proliferation, differentiation, invasion, and migration, which are all involved in embryo implantation, has been mentioned previously 6 , 47 , 48 . Active β-catenin levels were lower in SVX-mated mice compared to the control group on Day 5, which could be due to low levels of Wnt4 in this group and/or higher implantation rates in control mice than in the SVX-mated group. Lack of the appropriate regulatory effect of PGE2 on Wnt/β-catenin signaling could be another explanation for the decreased levels of active β-catenin in the uterus of SVX-mated mice, as PGE2 can strongly promote Wnt/β-catenin signaling 49 , and our previous study showed a lower expression of the genes involved in the PGE2 pathway in the uterus of SVX-mated mice 27 . It has been suggested that crosstalk between Wnt and prostaglandin signaling regulates uterine contraction and consequently embryo spacing 46 . In confirmation of this hypothesis, we found a correlation between active β-catenin levels and embryo spacing.

There was no significant difference in active β-catenin levels between the control group and SVX-mated group on Day 1 of pregnancy, which indicates that seminal vesicle secretion may not affect the catenin signaling pathway in the uterus following mating. Since one of the strong effects of seminal fluid deposition in the female reproductive tract is the induction of inflammation 29 and inflammation can activate noncanonical Wnt signaling 50 , it could be postulated that seminal vesicle signaling affects the noncanonical rather than the canonical signaling pathway.

Wnt5 expression also showed significant changes in the uterus during the pre-implantation window, as statistically lower expression was observed on Days 3 and 4 of pregnancy compared with the Day 1. As described for Wnt4, such a reduction could be due to hormonal changes and/or post-mating inflammatory responses. The latter cause of Wnt5 induction has been also reported in chondrocytes, where Wnt5a could be positively affected by inflammatory factors such as ILs 31 . As regards the influence of steroid hormones on Wnt5a, the results have been controversial as several studies reported no significant effect of estrogen on gene expression 12 , 51 , while others reported a stimulatory effect of the hormone on Wnt5a expression 20 . As Wnt5a expression on Days 1 and 2 of pregnancy was significantly lower in SVX-mated mice than in the control group, it could be postulated that the most effective factor in the regulation of gene expression, at least during the first two days of pregnancy, is seminal fluid-induced inflammation.

Wnt5a expression peaked on Day 5 of pregnancy, which could be for a number of different reasons:

Implantation- and/or embryo-induced increase, as there was a positive correlation between implantation rate and expression. Furthermore, expression was higher in the control group with a higher implantation rate than in the group of SVX-mated mice which had a lower number of implantation sites. Previous studies have reported increased expression of the gene at the site of blastocyst implantation 11 .

Induction by the decidualization process, which starts on Day 4.5 of pregnancy in mice and requires Wnt5a in appropriate amounts 21 .

Enhanced expression following an increase in progesterone production levels 42 .

We observed positive correlations between Wnt5a and Fzd2, Fzd6 and active β-catenin in the first three days of pregnancy, which revealed a collaboration between Wnt5a and the receptors to induce catenin signaling on those days. However, there was no significant correlation between Wnt5a and Fzd6 and active β-catenin on pre-implantation Days 4 and 5. There was a negative correlation between Wnt5a and Fzd2 expression, suggesting that Wnt5a might be involved in uterine preparation for implantation through the canonical/β-catenin pathway during the first three days of pregnancy but plays a role via noncanonical signaling on Days 4 and 5. In support of this idea, the potential of Wnt5a to activate both canonical and noncanonical pathways has been demonstrated in other studies 52 . It has been reported that Wnt5a can either activate or antagonize canonical pathways 53 . Cha et al. 21 suggested that Wnt5a acts through the noncanonical signaling pathway to induce decidualization. In view of the positive correlation between β-catenin and implantation rates and the importance of noncanonical signaling for implantation and decidualization, it could be postulated that Wnt5 acts as a modulator for canonical signaling in favor of the noncanonical pathway near the time of implantation.

The expression of Fzd2 also fluctuated during the pre-implantation window as expression peaking on Days 2 and 5 of pregnancy. The reason for the increased expression on Day 2 could be due to the elimination of estrogen inhibitory influence, which has been confirmed in previous studies 12 , 20 . The relatively high expression of Fzd2 on the day of implantation could pave the way for embryo implantation and decidualization, although there was no significant correlation between this factor and implantation rates. Increased mRNA levels of Fzd2 in endometrial stroma in mice around the implantation site has been reported in other studies 12 .

One limitation of our study was that it was not possible to confirm the results using an in vitro study due to low volume of SP in mouse. Moreover, we did not evaluate implantation and non-implantation sites separately. The evaluation of SP effects on different uterine cells, especially on endometrial cells such as epithelial and stroma, could be helpful to explain our results. Further studies are therefore needed to consider these issues.

In conclusion, our study showed significant changes in the mRNA expression of Wnt4, Wnt5a, Fzd2, and Fzd6 and in the protein levels of active β-catenin during the pre-implantation window. There were significant correlations between the expression of Wnt4, Wnt5a and active β-catenin and implantation rates and embryo spacing. A lack of seminal vesicle secretions during mating could significantly affect Wnt4, Wnt5a and Fzd2 expression as well as active β-catenin levels in mice uteri during the pre-implantation period, especially on the day after mating and the day of implantation.

Acknowledgements

The study was financially supported by the Womenʼs Reproductive Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (grant number of 4/9-5/94) and the paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Zeinab Latifi.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Latifi Z, Fattahi A, Ranjbaran A. Potential roles of metalloproteinases of endometrium-derived exosomes in embryo-maternal crosstalk during implantation. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:4530–4545. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang S, Lin H, Kong S. Physiological and molecular determinants of embryo implantation. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:939–980. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nejabati H R, Latifi Z, Ghasemnejad T. Placental growth factor (PlGF) as an angiogenic/inflammatory switcher: lesson from early pregnancy losses. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2017;33:668–674. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1318375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logan C Y, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brembeck F H, Rosário M, Birchmeier W. Balancing cell adhesion and Wnt signaling, the key role of beta-catenin. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xueling G E, Wang X. Role of Wnt canonical pathway in hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franco H L, Dai D, Lee K Y. WNT4 is a key regulator of normal postnatal uterine development and progesterone signaling during embryo implantation and decidualization in the mouse. FASEB J. 2011;25:1176–1187. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-175349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonderegger S, Pollheimer J, Knöfler M. Wnt signalling in implantation, decidualisation and placental differentiation–review. Placenta. 2010;31:839–847. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Xie Y, Dong M. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway regulates beta1, 4-galactosyltransferase l expression in the endometrium to affect the embryo implantation. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10:1756–1764. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi K, Yoshioka S, Reardon S N. WNTs in the neonatal mouse uterus: potential regulation of endometrial gland development. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:308–319. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goad J, Ko Y-A, Kumar M. Differential Wnt signaling activity limits epithelial gland development to the anti-mesometrial side of the mouse uterus. Dev Biol. 2017;423:138–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi K, Erikson D W, Tilford S A. Wnt genes in the mouse uterus: potential regulation of implantation. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:989–1000. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corda G, Sala A. Non-canonical WNT/PCP signalling in cancer: Fzd6 takes centre stage. Oncogenesis. 2017;6:e364. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2017.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyons J P, Mueller U W, Ji H. Wnt-4 activates the canonical beta-catenin-mediated Wnt pathway and binds Frizzled-6 CRD: functional implications of Wnt/beta-catenin activity in kidney epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2004;298:369–387. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daikoku T, Song H, Guo Y. Uterine Msx-1 and Wnt4 signaling becomes aberrant in mice with the loss of leukemia inhibitory factor or Hoxa-10: evidence for a novel cytokine-homeobox-Wnt signaling in implantation. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1238–1250. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herington J L, Bi J, Martin J D. Beta-catenin (CTNNB1) in the mouse uterus during decidualization and the potential role of two pathways in regulating its degradation. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:963–974. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7199.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tepekoy F, Akkoyunlu G, Demir R. The role of Wnt signaling members in the uterus and embryo during pre-implantation and implantation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:337–346. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0409-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endo M, Nishita M, Fujii M. Insight into the role of Wnt5a-induced signaling in normal and cancer cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2015;314:117–148. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C, Chen H, Hu L. Ror2 modulates the canonical Wnt signaling in lung epithelial cells through cooperation with Fzd2. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou X, Tan Y, Li M. Canonical Wnt signaling is critical to estrogen-mediated uterine growth. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:3035–3049. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cha J, Bartos A, Park C. Appropriate crypt formation in the uterus for embryo homing and implantation requires Wnt5a-ROR signaling. Cell Rep. 2014;8:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuoka A, Kizuka F, Lee L. Progesterone increases manganese superoxide dismutase expression via a cAMP-dependent signaling mediated by noncanonical Wnt5a pathway in human endometrial stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:E291–E299. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson S A, Prins J R, Sharkey D J. Seminal fluid and the generation of regulatory T cells for embryo implantation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69:315–330. doi: 10.1111/aji.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson S A, Guerin L R, Moldenhauer L M. Activating T regulatory cells for tolerance in early pregnancy–the contribution of seminal fluid. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;83:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson S A, Guerin L R, Bromfield J J. Seminal fluid drives expansion of the CD4+ CD25+ T regulatory cell pool and induces tolerance to paternal alloantigens in mice. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:1036–1045. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.074658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharkey D J, Tremellen K P, Jasper M J. Seminal fluid induces leukocyte recruitment and cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression in the human cervix after coitus. J Immunol. 2012;188:2445–2454. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahnazi M, Nouri M, Mohaddes G.Prostaglandin E pathway in uterine tissue during window of preimplantation in female mice mated with intact and seminal vesicle-excised male Reprod Sci 201825550–558.doi:10.1177/1933719117718272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharkey D J, Tremellen K P, Briggs N E. Seminal plasma pro-inflammatory cytokines interferon-γ (IFNG) and CXC motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8) fluctuate over time within men. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:1373–1381. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Troedsson M. Uterine response to semen deposition in the mare. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Society for Theriogenology; 1995 Sept 13 – 15, San Antonio, TX. pp. 130–135.

- 30.Sonomoto K, Yamaoka K, Oshita K. Interleukin-1β induces differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts via the Wnt-5a/receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 2 pathway. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3355–3363. doi: 10.1002/art.34555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ge X P, Gan Y H, Zhang C G. Requirement of the NF-κB pathway for induction of Wnt-5A by interleukin-1β in condylar chondrocytes of the temporomandibular joint: functional crosstalk between the Wnt-5A and NF-κB signaling pathways. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oguma K, Oshima H, Aoki M. Activated macrophages promote Wnt signalling through tumour necrosis factor-alpha in gastric tumour cells. EMBO J. 2008;27:1671–1681. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doncel G F, Anderson S, Zalenskaya I. Role of semen in modulating the female genital tract microenvironment–implications for HIV transmission. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:564–574. doi: 10.1111/aji.12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.North T E, Babu I R, Vedder L M. PGE2-regulated wnt signaling and N-acetylcysteine are synergistically hepatoprotective in zebrafish acetaminophen injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17315–17320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008209107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svala E, Thorfve A I, Ley C. Effects of interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β on expression of growth differentiation factor-5 and Wnt signaling pathway genes in equine chondrocytes. Am J Vet Res. 2014;75:132–140. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.75.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fattahi A, Darabi M, Farzadi L. Effects of dietary omega-3 and-6 supplementations on phospholipid fatty acid composition in mice uterus during window of pre-implantation. Theriogenology. 2018;108:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2017.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deb K, Reese J, Paria B C. Humana Press; 2006. Placenta and Trophoblast: Methodologies to study Implantation in Mice; pp. 9–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livak K J, Schmittgen T D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, Dey S K. Roadmap to embryo implantation: clues from mouse models. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:185–199. doi: 10.1038/nrg1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mccormack J, Greenwald G. Progesterone and oestradiol-17β concentrations in the peripheral plasma during pregnancy in the mouse. J Endocrinol. 1974;62:101–107. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0620101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamura T, Miyagawa S, Katsu Y. Sequential changes in the expression of Wnt-and Notch-related genes in the vagina and uterus of ovariectomized mice after estrogen exposure. In Vivo. 2012;26:899–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rider V, Talbott A, Bhusri A. WINGLESS (WNT) signaling is a progesterone target for rat uterine stromal cell proliferation. J Endocrinol. 2016;229:197–207. doi: 10.1530/JOE-15-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robertson S. Seminal fluid signaling in the female reproductive tract: lessons from rodents and pigs. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:E36–E44. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robertson S, Mau V, Tremellen K. Role of high molecular weight seminal vesicle proteins in eliciting the uterine inflammatory response to semen in mice. J Reprod Fertil. 1996;107:265–277. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1070265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramathal C Y, Bagchi I C, Taylor R N. Endometrial decidualization: of mice and men. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28:17–26. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Q, Zhang Y, Lu J. Embryo-uterine cross-talk during implantation: the role of Wnt signaling. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;15:215–221. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mège R M, Gavard J, Lambert M. Regulation of cell-cell junctions by the cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gama A, Paredes J, Gärtner F. Expression of E-cadherin, P-cadherin and beta-catenin in canine malignant mammary tumours in relation to clinicopathological parameters, proliferation and survival. Vet J. 2008;177:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J-Y, Bai X-M, Zhang L. PGE_2 promotes endometrial cancer cell growth through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [J] Acta Universitatis Medicinalis Nanjing (Natural Science) 2011:31. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Catalán V, Gómez-Ambrosi J, Rodríguez A. Activation of noncanonical Wnt signaling through WNT5A in visceral adipose tissue of obese subjects is related to inflammation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E1407–E1417. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kiewisz J, Kaczmarek M M, Morawska E. Estrus synchronization affects WNT signaling in the porcine reproductive tract and embryos. Theriogenology. 2011;76:1684–1694. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ring L, Neth P, Weber C. β-Catenin-dependent pathway activation by both promiscuous “canonical” WNT3a–, and specific “noncanonical” WNT4–and WNT5a–FZD receptor combinations with strong differences in LRP5 and LRP6 dependency. Cell Signal. 2014;26:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Topol L, Jiang X, Choi H. Wnt-5a inhibits the canonical Wnt pathway by promoting GSK-3-independent beta-catenin degradation. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:899–908. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]