ABSTRACT

Low-level rifampin resistance associated with specific rpoB mutations (referred as “disputed”) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is easily missed by some phenotypic methods. To understand the mechanism by which some mutations are systematically missed by MGIT phenotypic testing, we performed an in silico analysis of their effect on the structural interaction between the RpoB protein and rifampin. We also characterized 24 representative clinical isolates by determining MICs on 7H10 agar and testing them by an extended MGIT protocol. We analyzed 2,097 line probe assays, and 156 (7.4%) cases showed a hybridization pattern referred to here as “no wild type + no mutation.” Isolates harboring “disputed” mutations (L430P, D435Y, H445C/L/N/S, and L452P) tested susceptible in MGIT, with prevalence ranging from 15 to 57% (overall, 16 out of 55 isolates [29%]). Our in silico analysis did not highlight any difference between “disputed” and “undisputed” substitutions, indicating that all rpoB missense mutations affect the rifampin binding site. MIC testing showed that “undisputed” mutations are associated with higher MIC values (≥20 mg/liter) compared to “disputed” mutations (4 to >20 mg/liter). Whereas “undisputed” mutations didn't show any delay (Δ) in time to positivity of the test tube compared to the control tube on extended MGIT protocol, “disputed” mutations showed a mean Δ of 7.2 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.2 to 10.2 days; P < 0.05), providing evidence that mutations conferring low-level resistance are associated with a delay in growth on MGIT. Considering the proved relevance of L430P, D435Y, H445C/L/N, and L452P mutations in determining clinical resistance, genotypic drug susceptibility testing (DST) should be used to replace phenotypic results (MGIT) when such mutations are found.

KEYWORDS: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, diagnostics, drug susceptibility testing, multidrug resistance

INTRODUCTION

Molecular approaches identifying mutations conferring drug resistance represent a revolution in the field of tuberculosis (TB), shortening the time to diagnosis from months to hours. Indeed, culture-based conventional phenotypic drug susceptibility testing (DST) has a time frame too long for proper patient management (1). The molecular diagnostics landscape offers a wide panel of new molecular assays, especially in high-income countries. Among them, the GenoType MTBDRplus line probe assay (LiPA) (Hain, Nehren, Germany) and the Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) assays are valuable alternatives for the rapid detection of rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with rapid and highly specific results (2–4). However, whereas the presence of specific and well-known mutations in the rifampin resistance-determining region (RRDR) of the rpoB gene allows easy interpretation of molecular DST and consequent clinical decision, less common mutations often not specifically targeted by the current assays, such as those based on LiPA technology, are more difficult to interpret. Indeed, commercially available LiPAs specifically target only a few mutations (D435V, H445Y, H445D, and S450L), whereas the remaining mutations affecting the RRDR are inferred by the lack of hybridization of the wild-type probe. Hence, phenotypic DST methods for M. tuberculosis are still considered the “gold standard” for identification of rifampin resistance. Previous results indicated that low-level rifampin resistance associated with specific rpoB mutations (referred as “disputed”) is easily missed by some phenotypic methods, thus highlighting discrepancies between genotypic versus phenotypic testing and also between different testing media (5–16). While the relevant clinical implications of these findings have been described in several studies, the technical bases of these observations were not further elucidated. Given the urgent need for rapid and accurate DST methods, a more extensive understanding of discrepancies between phenotypic and genotypic approaches is needed. To this end, in this study we focused on discrepant cases between DST performed on the Bactec MGIT 960 (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) system and the “no-wild-type” pattern shown by some molecular assays. To understand the mechanism by which some mutations are systematically missed by MGIT phenotypic testing, we performed an in silico analysis of their effect on the structural interaction between the RpoB protein and rifampin. We also characterized a subset of representative clinical isolates by determining MICs on 7H10 agar and testing them by a modified (extended) MGIT protocol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection of strains.

We included in the study isolates available in our strain collection and previously tested with line probe assays (LiPAs) for the rapid detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance. We retrospectively identified 156 isolates tested with LiPAs (namely the GenoType MTBDR and the GenoType MTBDRplus version 1 or 2; Hain Lifescience, Nehren, Germany) showing a hybridization pattern for the rpoB gene in which at least one wild-type band was missing, without any further hybridization of bands identifying specific mutations (a hybridization pattern herewith referred to as “no wild type + no mutation”). From this starting data set, we selected 24 clinical isolates harboring specific mutations plus 10 control isolates with known mutations (Ser450Leu) or wild type (including the reference strain H37Rv) for the rpoB gene for further characterization based on a convenient sampling method.

DNA extraction.

DNA from isolates was extracted by thermal lysis and sonication as described elsewhere (17).

Sequencing.

All 156 isolates were sequenced by paired-end Sanger sequencing for the rifampin resistance-determining region (RRDR) of the rpoB gene for mutations responsible for rifampin resistance. The primers used and the detailed genomic region covered are available upon request. Direct sequencing of the PCR products was carried out with an ABI Prism 3100 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and an ABI Prism BigDye Terminator kit v.2.1 (Applied Biosystems) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Sequencing results were analyzed using BioEdit v.7.1.3.0 (18), aligning sequences with the corresponding reference strain (M. tuberculosis H37Rv; GenBank accession no. AL123456), and results were reported according to the M. tuberculosis numbering system (19).

Drug susceptibility testing.

Initial phenotyic drug susceptibility testing for rifampin was performed on the Bactec MGIT 960 (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) using 1 mg/liter as the critical concentration (CC), according to WHO recommendations (20). For this study, we further repeated phenotypic drug susceptibility testing on the Bactec MGIT 960 using one tube without rifampin as a control and another with 1 mg/liter rifampin added as a test tube. The protocol was set up with the BD EpiCenter TB extended individual susceptibility testing software (TB-eXiST, v.3.00c, 2011). The drug susceptibility testing (DST) was not considered over when the control tube reached 400 growth units (GU), but we followed up the results until the test tube with rifampin reached ≥100 GU, even if the control tube was already positive. The time to positivity (TTP) was defined as the number of days from sample inoculation to detection of mycobacterial growth. The TTPs of both the control and the test tubes were recorded in days, and the delay (Δ) between the growth observed in the control tube (≥400 GU) and the test tube (≥100 GU) was calculated as follows: Δ = TTPtest tube – TTPcontrol tube. The protocol stopped at day 42: thus, the maximum TTP used for calculations was 42 days.

Isolates were also tested further for determination of the MIC by the 7H10 agar method. The MIC was determined as previously recommended (21). Briefly, testing concentrations included 0.5, 1.0, 4.0, 10.0, and 20.0 mg/liter. Testing plates were read at day 21 if the control plate showed a minimum number of 20 visible colonies; otherwise plates were incubated for another week and eventually read at day 28. If no growth appeared at day 28, the test was repeated. For our purposes, we considered results in terms of the MIC99, the concentration of rifampin inhibiting 99% of the bacterial population. As a result, we considered 1% as a critical proportion. Results were reported both as MIC values and category (susceptible or resistant). Isolates were considered rifampin resistant on 7H10 agar medium when the MIC was found to be >1 mg/liter.

Data analysis.

For data analysis, first of all, we correlated rpoB mutations and phenotypic resistance in both MGIT and 7H10 media. Then, we correlated the rpoB mutations with the delay (Δ) observed in MGIT. To provide an overall picture, we compared by t test mutations associated with Δ in MGIT-susceptible, 7H10-resistant cases versus MGIT-resistant, 7H10-resistant cases and also Δ in MGIT-susceptible, 7H10-resistant cases versus MGIT-susceptible, 7H10-susceptible cases. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 v.5.04 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Structural analysis.

The effect on the protein structure of the mutations associated with Δ were evaluated using visual and computational analyses. First, the crystal structures of M. tuberculosis transcription initiation complex bound to rifampin (PDB codes 5UH6, 5UHB, 5UHC, 5UHD, and 5UHG) (22) were visualized with PyMOL software (the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.8; Schrödinger, LLC). Next, the effect on the protein stability of amino acid substitutions not directly in contact with the drug was calculated with the program FoldX, which uses a semiempirical energy function to evaluate the free-energy variation upon amino acid substitution (23). Briefly, the isolated complete RNA polymerase structure was subjected to an energy minimization to remove any steric clashes that involved side-chain atoms. Each rpoB mutation, individually or in combination, was introduced in the protein structure using the BuildModel module in FoldX, and the variation of the folding free energy (ΔΔG) compared to the wild-type protein was then computed. The procedure was repeated 5 times to ensure that the mutant structure was not trapped in local minima. Energy values were considered significantly destabilizing if greater than 2 times the standard deviation of the program. The variation in rifampin affinity toward RpoB mutants was calculated using the program mCSM-lig, which takes advantage of graph-based signatures of the environment of the mutations and does not require the direct modeling of the mutation (24).

RESULTS

A retrospective analysis of isolates tested on LiPAs in our laboratory showed 156 out of 2,097 (7.4%) cases harboring a hybridization pattern designated here “no wild type + no mutation” (details available upon request), and sequencing results are summarized in Table 1. The most frequently mutated codons were 445 (26.9%), 450 (19.2%), and 452 and 432 (8.3% each), followed by codons 435 (7.1%), 430 and 441 (3.2% each), and 431 (0.6%). Multiple mutations (single nucleotide polymorphisms) were found in 16.0% of cases, whereas nucleotide insertions and deletions (indels) were observed in 3.2% of samples. The presence of silent mutations accounted for 1.3% of “no wild type + no mutation” cases (two cases harboring the Q432Q and D435D mutations, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Isolates showing the pattern “no wild type + no mutation” on LiPA

| rpoB RRDR sequencing typea | No. of isolates with phenotypic DST resultb: |

Total no. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | S | ||

| D435D | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| D435L | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| D435V | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| D435Yc | 5 | 3 | 8 (5.1) |

| D435Y + L452P + G456V | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| del nt 1302–1310→GGACCAGAAd | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| del D435 | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| del D435 + E460Gd | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| del 435-L443F | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| S431Rd | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| dupl F433 | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| H445Cd | 3 | 3 (1.9) | |

| H445D | 3 | 3 (1.9) | |

| H445L | 7 | 2 | 9 (5.8) |

| H445Nc | 4 | 3 | 7 (4.5) |

| H445P | 2 | 2 (1.3) | |

| H445Qd | 5 | 5 (3.2) | |

| H445R | 5 | 5 (3.2) | |

| H445Sc | 3 | 4 | 7 (4.5) |

| H445S + L452P | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| H445Y | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| del nt 1295–1303→AATTCATGG | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| L430P | 3 | 1 | 4 (2.6) |

| L430P + D435G | 2 | 2 (1.3) | |

| L430P + D435Y | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| L430Q | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| L430R + D435Y | 2 | 2 (1.3) | |

| L449M + S450Pd | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| L452Pc | 11 | 2 | 13 (8.3) |

| M434I + D435Y | 2 | 2 (1.3) | |

| M434I + H445Nc | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| M434T + H445Sd | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| M434V + H445N | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| N437D + L452P | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| Q429V + D435Y | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| Q432E | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| Q432H + L452P | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| Q432K | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| Q432Ld | 4 | 4 (2.6) | |

| Q432P | 6 | 6 (3.8) | |

| Q432P + H445S | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| Q432Q | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| S431R + H445N | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| S431T + M434I + H445N | 3 | 3 (1.9) | |

| S441L + H445Q | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| S441L + S450A | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| S441Q | 3 | 3 (1.9) | |

| S441W | 2 | 2 (1.3) | |

| S450Fd | 2 | 2 (1.3) | |

| S450L | 4 | 4 (2.6) | |

| S450Q | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| S450Y | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| S450W | 22 | 22 (14.1) | |

| T444T + H445P + K446Q | 1 | 1 (0.6) | |

| Wild type | 6 | 6 (3.8) | |

| Total | 139 | 17 | 156 |

del, deletion; nt, nucleotide; dupl, duplication.

R, resistant; S, susceptible.

Mutations selected among rifampin-susceptible isolates for further characterization.

Mutations selected among rifampin-resistant isolates for further characterization.

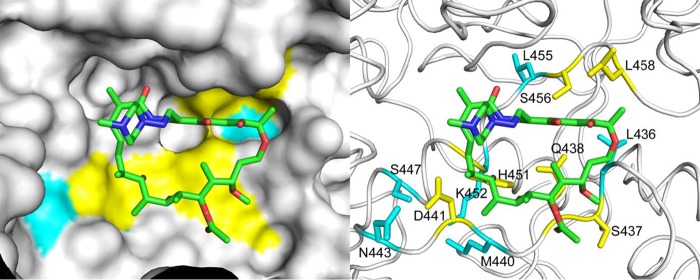

In order to ascertain whether the “disputed” mutations (L430P, D435Y, H445C, H445L, H445N, H445S, and L452P) could differentially affect rifampin binding to the RpoB protein compared to the “undisputed” ones, we analyzed in silico the effects of all amino acid substitutions presented here. Visual inspection of the structure of M. tuberculosis RNA polymerase in complex with DNA, nascent RNA, and rifampin (22) reveals that all missense mutations in the rpoB gene affect the rifampin binding site (Fig. 1) and define a contiguous molecular surface in direct contact with the drug. In order to investigate the effect of the observed mutations on the RpoB protein structure, we performed an in silico analysis using the program FoldX, which computes the variation in folding energy (ΔΔG) following amino acid replacements (details available upon request). Of all mutations considered, only five (S431R, S441Q, S441W, S450F, and S450Y) had a significantly destabilizing effect (at least 0.92 kcal/mol, corresponding to twice the standard deviation of the computed energies by the program compared to the experimental values). We used the program mCSM-lig to evaluate the effect of each mutation on the binding affinity toward rifampin (details available upon request). The computed variations in affinity of the “disputed” and “undisputed” mutations were not statistically significant (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Structural representation of the residues involved in the RpoB and rifampin interaction. (Left) Molecular surface of the RpoB protein (shown in white) with the bound rifampin depicted as sticks. The mutated amino acids formed are all located within 5 Å of the drug and define a contiguous surface in the binding cavity. Both “undisputed” (colored cyan) and “disputed” (yellow) mutations affect amino acids directly involved in shaping the rifampin binding site. The coordinates of RpoB and rifampin were taken from the PDB deposition 5UHB. (Right) The side chains of the mutated amino acids are shown as sticks. Since the resolution of the X-ray data used in the structure determination was lower than 3.5 Å, hydrogen bonds between RpoB and rifampin could not be unequivocally assigned. (The PDB numbering system = the MTB numbering system + 6).

We selected 24 isolates harboring 14 mutations (tagged in Table 1) representative of the hybridization pattern “no wild-type + no mutation” for further characterization by extended phenotypic DST in MGIT and MIC determination on 7H10 agar medium This selection included isolates harboring “disputed” mutations sometimes found to be associated with rifampin susceptibility on MGIT testing (D435Y, H445C, H445N, H445S, and L452P), as well as “undisputed” mutations found in rifampin-resistant isolates (S431R, Q432L, H445Q, S450F, M434I + H445N, deletion at codons 434 to 437, deletion at codon 435 + E460G, L449M + S450P, and M434T + H445S). In addition, as controls we included 2 rifampin-resistant isolates harboring an in-frame mutation affecting codon 445 (insertion of AAC at nucleotide position 1334), and the S450L mutation, respectively. Seven rifampin-susceptible wild-type isolates and one rifampin-susceptible isolate harboring a silent mutation (P454P) were also included. All the details for the selected strains are available upon request.

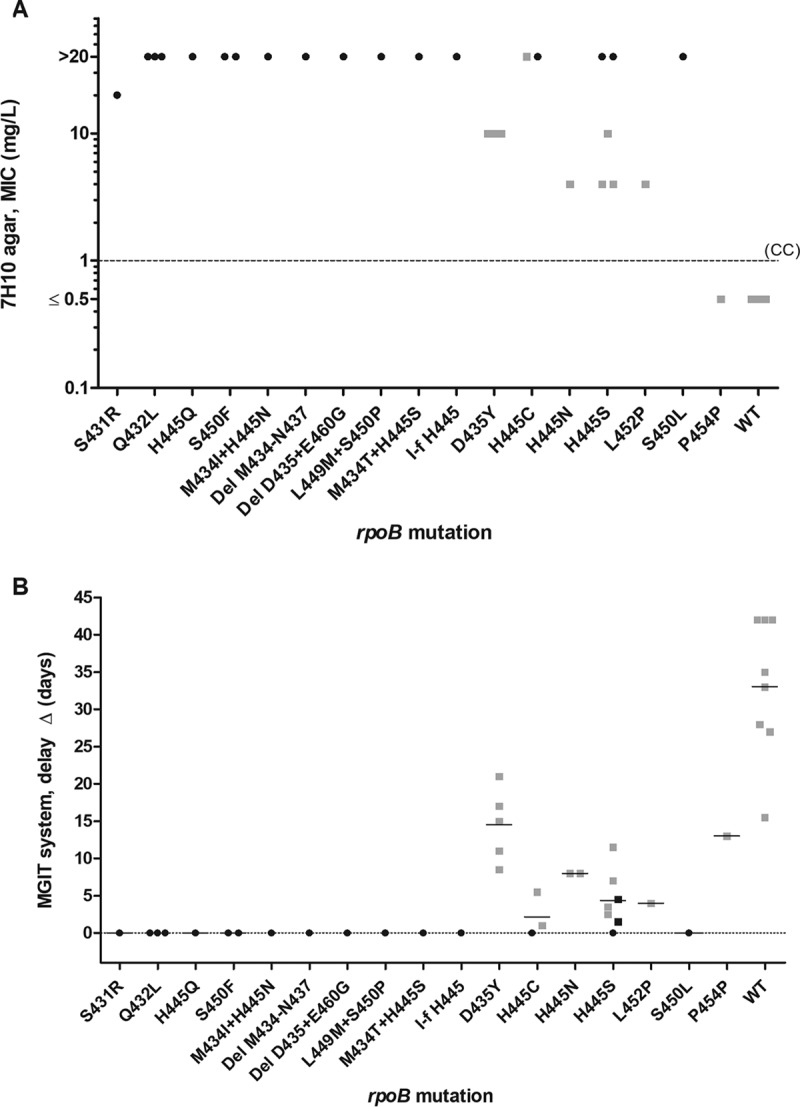

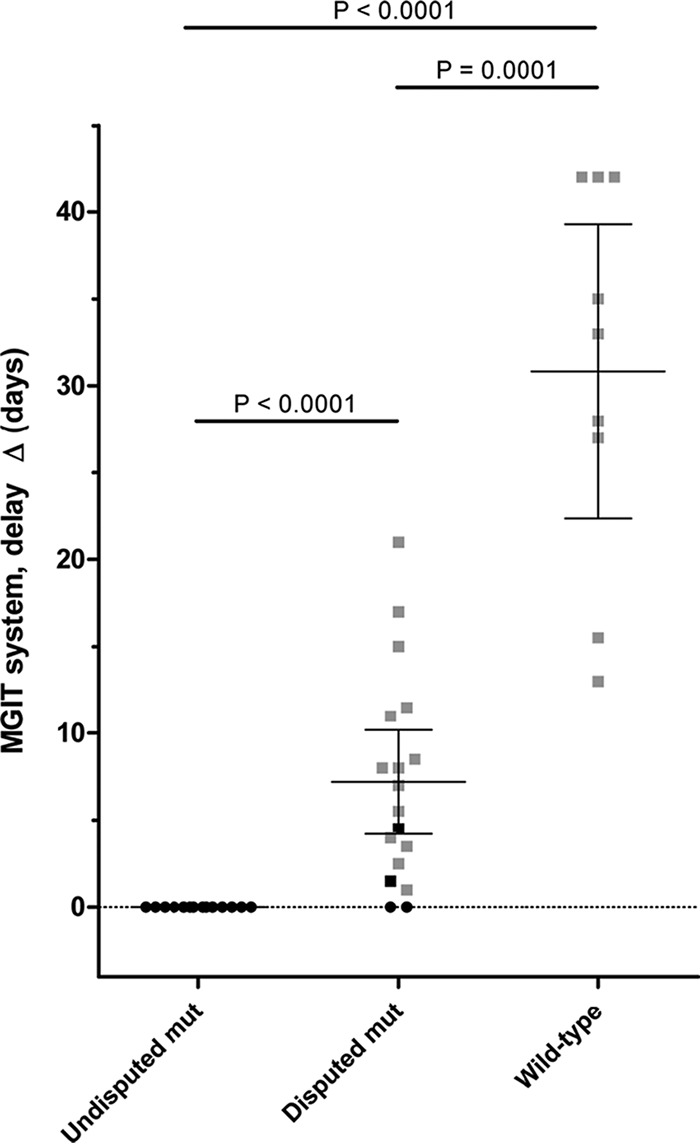

MIC testing on 7H10 agar medium showed that any amino acidic substitution or insertion/deletion in the RRDR was associated with rifampin resistance (CC, 1 mg/liter), with MICs ranging from 4 to >20 mg/liter (Fig. 2A). In general, “undisputed” mutations showed higher minimum inhibitory values (≥20 mg/liter) compared to “disputed” mutations (from 4 to >20 mg/liter). All wild-type isolates (including the one harboring the P454P silent mutation) showed MICs of ≤0.5 mg/liter. The same isolates tested for MIC were retested on MGIT using the TB-eXiST protocol. As shown in Fig. 2B, “undisputed” mutations did not show any delay (Δ) in the TTP of the test tube compared to the control tube (mean Δ of 0 days), whereas “disputed” mutations showed different degrees of Δ; six rifampin-susceptible cases according to standard MGIT phenotypic DST showing a Δ in the TB-eXiST protocol were tested twice to confirm our findings (1 H445C, 1 H445N, 2 D435Y, and 2 H445S). Similarly, one rifampin-resistant case according to standard MGIT phenotypic DST showing a Δ in the TB-eXiST protocol was tested twice (H445S). As shown in Fig. 3, “disputed” mutations showed a mean Δ of 7.2 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.2 to 10.2 days). As expected, wild-type isolates showed the highest Δ (mean Δ, 30.8 days; 95% CI, 22.4 to 39.3 days). The differences observed in the Δ among the 3 categories of isolates (namely harboring “undisputed” mutations, “disputed” mutations, or no mutations) were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

FIG 2.

(A) MIC (MIC99) values by 7H10 agar proportion phenotypic drug susceptibility testing for selected mutations. (B) Delay (Δ) in the time to positivity (TTP) results between the control and the test tube using the TB-eXiST protocol on MGIT for selected mutations. Note that in 1 case of H445C, 1 case of H445N, 2 cases of D435Y, and 2 cases of H445S, isolates for which rifampin susceptibility was found were tested twice. Similarly, 1 case of rifampin resistance (H445S) was tested twice. Squares represent mutations associated with a Δ of >0 using the MGIT TB-eXiST protocol, and circles represent mutations not associated with any delay by the MGIT TB-eXiST protocol. Black indicates phenotypically resistant to rifampin according to standard MGIT drug susceptibility testing, and gray indicates phenotypically susceptible to rifampin according to standard MGIT drug susceptibility testing. CC, critical concentration. Δ = TTPtest tube – TTPcontrol tube. In panel B, mean values are also indicated (horizontal bars).

FIG 3.

Comparison between the delay (Δ) in the time to positivity (TTP) results using the TB-eXiST protocol on MGIT for “undisputed” and “disputed” mutations and wild-type isolates. The wild-type results include as well the P454P silent mutation. Δ values are reported together with mean and 95% confidence intervals. Squares represent mutations associated with a Δ of >0 on the MGIT TB-eXiST protocol, and circles represent mutations not associated with any delay on MGIT TB-eXiST protocol. Black indicates phenotypically resistant to rifampin according to standard MGIT drug susceptibility testing, and gray indicates phenotypically susceptible to rifampin according to standard MGIT drug susceptibility testing. Δ = TTPtest tube – TTPcontrol tube. Mean values are indicated by horizontal bars.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide further insights in understanding discrepancies between genotypic and phenotypic results for rifampin DST. In particular, we decided to focus our attention on mutations (i) associated with the hybridization pattern “no wild type + no mutation” on line probe assays and (ii) testing susceptible on conventional MGIT phenotypic DST. The majority of such mutations were associated with rifampin resistance (133 out of 150 [88.7%]), whereas more than 10% were found in isolates that tested phenotypically susceptible on conventional MGIT (CC, 1 mg/liter).

Notably, we found that isolates harboring “disputed” L430P, D435Y, H445L/N, or L452P mutations tested susceptible on MGIT with prevalences ranging from 15 to 43% (overall, 12 out of 48 isolates [25%]). Previous studies described similar findings, despite a resistant phenotype being observed when other testing media were used (7). All these mutations have also been proven to be associated with relapse or treatment failure in clinical settings (8). Our analysis added the H445S variant (associated with a susceptible phenotype in MGIT in 57% of cases) to the list of “disputed” mutations, thus making codon 445 the position most affected by debatable mutations in the RRDR (9 out of 42 cases [21.4%]) (25). In order to unveil the role of these mutations in determining a susceptible or resistant phenotypic result, we provided further characterization by MIC testing on 7H10 agar and using an extended protocol for MGIT with the TB-eXiST software on a subset of M. tuberculosis strains. The “disputed” mutations tested resistant on 7H10 agar medium (CC of 1 mg/liter) like the control isolates harboring mutations associated with rifampin resistance (26).

Interestingly, the extended protocol used on the MGIT system highlighted a difference in the TTPs of strains affected by “disputed” mutations. Indeed, isolates harboring D435Y, H445C/N/S, or L452P showed a mean delay (Δ) of 7.2 days (95% CI, 4.2 to 10.2 days), suggesting that these mutations might somehow cause a defective growth rate during rifampin exposure. Susceptible cases showed a significantly higher delay in TTP (mean Δ, 30.8 days; 95% CI, 22.4 to 39.3 days) compared to “disputed” ones: note that the protocol was stopped at day 42, thus for such strains, the Δ is likely underestimated. This confirms our findings that isolates with “disputed” mutations are associated with growth impairment in MGIT rifampin DST.

It was hypothesized that such mutations were somehow responsible for a limited (or absent) effect on the RpoB-rifampin interaction, thus justifying their susceptible phenotype on MGIT. Rifampin inhibits bacterial RNA polymerases through the steric occlusion of the exit tunnel of the nascent oligonucleotide chain, and resistance to rifampin is caused by mutations in the RRDR affecting directly the rifampin binding site (Fig. 1) (25). These substitutions are all located within 5.0 Å of the bound rifampin in the crystal structures and result in either removal of direct contacts between RpoB and the drug or disruption of interactions that shape the binding site (Fig. 1). Neither physicochemical characteristic of the amino acid substitutions (e.g., introduction of a charge or variations of the size of the mutated residue) was associated with the “disputed” mutations, nor could a stabilizing/destabilizing effect be associated with a unique phenotype: our analysis using mCSM-lig showed that apparently the different behavior of mutants in liquid culture cannot be directly ascribed to specific effects on the binding affinity (Fig. S1). However, since the program does not account for variations in the binding mode between RpoB and rifampin, it is possible that the “disputed” mutations leading to a delay in growth reduce the affinity but do not completely prevent rifampin from binding to RpoB. This partial inhibitory effect is then overcome in the liquid conditions, possibly due to differences in metabolic profile of the bacteria compared to the growth on solid media. This hypothesis is supported by a molecular dynamics analysis that showed how specific mutations at residue H445 could retain drug binding to the RpoB protein, albeit in a different conformation that may allow RNA synthesis to proceed (27). Studies on the affinity and kinetics of rifampin binding to these mutants could provide further insights into a molecular basis for the observed delay in growth. Furthermore, we performed a preliminary analysis of the sequence of rpoA and rpoC genes looking for compensatory mutations; however, we did not detect any of the mutations previously described for rifampin-resistant isolates (28–31) (details available upon request). In addition, the mutations we found were observed in both isolates showing a Δ of >0 and those not showing any delay: thus, further studies are needed to rule out any role in fitness costs for mutations associated with a delayed growth in MGIT.

For the first time, our data provide further details on the basics of the discrepancies between genotypic and phenotypic DST for rifampin, suggesting that mutations conferring low-level resistance are associated with a delay in growth on MGIT phenotypic testing. Mutations frequently missed by MGIT are L430P, D435Y, S441Q, H445L, H445C, H445N, H445S, and L452P; accordingly, between 2 and 3% of rifampin-resistant cases could be missed by MGIT testing. Moreover, the prevalence of such mutations can vary across different geographical regions. Considering the proven relevance of L430P, D435Y, H445C, H445L, H445N, and L452P mutations in determining clinical resistance, as documented by different studies (6, 8, 10, 13–15, 32), genotypic DST should be used to replace phenotypic MGIT results when such specific mutations are found.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For this publication, the research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement FP7-223681 to D.M.C. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01599-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Somoskovi A, Salfinger M. 2015. The race is on to shorten the turnaround time for diagnosis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 53:3715–3718. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02398-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. 2008. WHO policy statement: molecular line probe assays for rapid screening of patients at risk of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. 2013. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB in adults and children—policy update. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. 2017. WHO Meeting Report of a Technical Expert Consultation: non-inferiority analysis of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra compared to Xpert MTB/RIF. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Deun A, Barrera L, Bastian I, Fattorini L, Hoffmann H, Kam KM, Rigouts L, Rusch-Gerdes S, Wright A. 2009. Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains with highly discordant rifampin susceptibility test results. J Clin Microbiol 47:3501–3506. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01209-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson DA, Roberts SA, Bower JE, Vaughan R, Newton S, Lowe O, Lewis CA, Freeman JT. 2012. Clinical failures associated with rpoB mutations in phenotypically occult multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 16:216–220. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rigouts L, Gumusboga M, de Rijk WB, Nduwamahoro E, Uwizeye C, de Jong B, Van Deun A. 2013. Rifampin resistance missed in automated liquid culture system for Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with specific rpoB mutations. J Clin Microbiol 51:2641–2645. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02741-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Deun A, Aung KJ, Bola V, Lebeke R, Hossain MA, de Rijk WB, Rigouts L, Gumusboga A, Torrea G, de Jong BC. 2013. Rifampin drug resistance tests for tuberculosis: challenging the gold standard. J Clin Microbiol 51:2633–2640. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00553-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somoskovi A, Deggim V, Ciardo D, Bloemberg GV. 2013. Diagnostic implications of inconsistent results obtained with the Xpert MTB/Rif assay in detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with an rpoB mutation associated with low-level rifampin resistance. J Clin Microbiol 51:3127–3129. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01377-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho J, Jelfs P, Sintchencko V. 2013. Phenotypically occult multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis: dilemmas in diagnosis and treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:2915–2920. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ocheretina O, Escuyer VE, Mabou MM, Royal-Mardi G, Collins S, Vilbrun SC, Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW. 2014. Correlation between genotypic and phenotypic testing for resistance to rifampin in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates in Haiti: investigation of cases with discrepant susceptibility results. PLoS One 9:e90569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamieson FB, Guthrie JL, Neemuchwala A, Lastovetska O, Melano RG, Mehaffy C. 2014. Profiling of rpoB mutations and MICs for rifampin and rifabutin in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 52:2157–2162. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00691-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ocheretina O, Shen L, Escuyer VE, Mabou MM, Royal-Mardi G, Collins SE, Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW. 2015. Whole genome sequencing investigation of a tuberculosis outbreak in Port-au-Prince, Haiti caused by a strain with a “low-level” rpoB mutation L511P—insights into a mechanism of resistance escalation. PLoS One 10:e0129207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Deun A, Aung KJ, Hossain A, de Rijk P, Gumusboga M, Rigouts L, de Jong BC. 2015. Disputed rpoB mutations can frequently cause important rifampicin resistance among new tuberculosis patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 19:185–190. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah NS, Grace Lin SY, Barry PM, Cheng YN, Schecter G, Desmond E. 2016. Clinical impact on tuberculosis treatment outcomes of discordance between molecular and growth-based assays for rifampin resistance, California 2003-2013. Open Forum Infect Dis 3:ofw150. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalo X, Claxton P, Brown T, Montgomery L, Fitzgibbon M, Laurenson I, Drobniewski F. 2017. True rifampicin resistance missed by the MGIT: prevalence of this pheno/genotype in the UK and Ireland after 18 month surveillance. Clin Microbiol Infect 23:260–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miotto P, Saleri N, Dembelé M, Ouedraogo M, Badoum G, Pinsi G, Migliori GB, Matteelli A, Cirillo DM. 2009. Molecular detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance to guide chronic TB patient management in Burkina Faso. BMC Infect Dis 9:142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall TA. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andre E, Goeminne L, Cabibbe A, Beckert P, Kabamba Mukadi B, Mathys V, Gagneux S, Niemann S, Van Ingen J, Cambau E. 2017. Consensus numbering system for the rifampicin resistance-associated rpoB gene mutations in pathogenic mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect 23:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Global Laboratory Initiative. 2014. Mycobacteriology laboratory manual. Stop TB Partnership, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2011. M24-A2 susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes; approved standard, 2nd ed, vol 13 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin W, Mandal S, Degen D, Liu Y, Ebright YW, Li S, Feng Y, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Liu S, Gigliotti M, Talaue M, Connell N, Das K, Arnold E, Ebright RH. 2017. Structural basis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcription and transcription inhibition. Mol Cell 66:169–179.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schymkowitz J, Borg J, Stricher F, Nys R, Rousseau F, Serrano L. 2005. The FoldX web server: an online force field. Nucleic Acids Res 33:W382–W388. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pires DE, Blundell TL, Ascher DB. 2016. mCSM-lig: quantifying the effects of mutations on protein-small molecule affinity in genetic disease and emergence of drug resistance. Sci Rep 6:29575. doi: 10.1038/srep29575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Telenti A, Imboden P, Marchesi F, Lowrie D, Cole S, Colston MJ, Matter L, Schopfer K, Bodmer T. 1993. Detection of rifampicin-resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet 341:647–650. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90417-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miotto P, Tessema B, Tagliani E, Chindelevitch L, Starks AM, Emerson C, Hanna D, Kim PS, Liwski R, Zignol M, Gilpin C, Niemann S, Denkinger CM, Fleming J, Warren RM, Crook D, Posey J, Gagneux S, Hoffner S, Rodrigues C, Comas I, Engelthaler DM, Murray M, Alland D, Rigouts L, Lange C, Dheda K, Hasan R, Ranganathan UDK, McNerney R, Ezewudo M, Cirillo DM, Schito M, Köser CU, Rodwell TC. 2017. A standardised method for interpreting the association between mutations and phenotypic drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 50:1701354. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01354-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh A, Grover S, Sinha S, Das M, Somvanshi P, Grover A. 2017. Mechanistic principles behind molecular mechanism of rifampicin resistance in mutant RNA polymerase beta subunit of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Cell Biochem 118:4594–4606. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comas I, Borrell S, Roetzer A, Rose G, Malla B, Kato-Maeda M, Galagan J, Niemann S, Gagneux S. 2011. Whole-genome sequencing of rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains identifies compensatory mutations in RNA polymerase genes. Nat Genet 44:106–110. doi: 10.1038/ng.1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brandis G, Wrande M, Liljas L, Hughes D. 2012. Fitness-compensatory mutations in rifampicin-resistant RNA polymerase. Mol Microbiol 85:142–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Vos M, Müller B, Borrell S, Black PA, van Helden PD, Warren RM, Gagneux S, Victor TC. 2013. Putative compensatory mutations in the rpoC gene of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis are associated with ongoing transmission. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:827–832. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01541-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li QJ, Jiao WW, Yin QQ, Xu F, Li JQ, Sun L, Xiao J, Li YJ, Mokrousov I, Huang HR, Shen AD. 2016. Compensatory mutations of rifampin resistance are associated with transmission of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype strains in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2807–2812. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02358-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Ingen J, Aarnoutse R, de Vries G, Boeree MJ, van Soolingen D. 2011. Low-level rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains raise a new therapeutic challenge. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 15:990–992. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.