Abstract

Background

Recruiting ethnically diverse Black participants to an innovative, community-based research study to reduce colorectal cancer screening disparities requires multipronged recruitment techniques.

Objectives

This paper describes active, passive, and snowball recruitment techniques, and challenges and lessons learned in recruiting a diverse sample of Black participants.

Methods

For each of the three recruitment techniques, data were collected on strategies, enrollment efficiency (participants enrolled/participants evaluated), and reasons for ineligibility.

Results

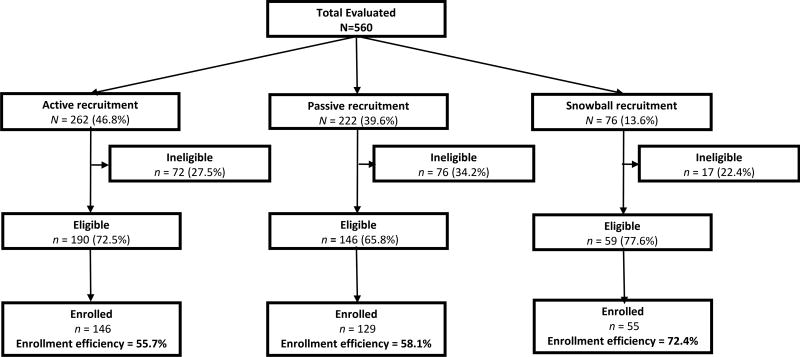

Five hundred and sixty individuals were evaluated, and 330 individuals were enrolled. Active recruitment yielded the highest number of enrolled participants, followed by passive and snowball. Snowball recruitment was the most efficient technique, with enrollment efficiency of 72.4%, followed by passive (58.1%) and active (55.7%) techniques. There were significant differences in gender, education, country of origin, health insurance, and having a regular physician by recruitment technique (p < .05).

Discussion

Multipronged recruitment techniques should be employed to increase reach, diversity, and study participation rates among Blacks. Although each recruitment technique had a variable enrollment efficiency, the use of multipronged recruitment techniques can lead to successful enrollment of diverse Blacks into cancer prevention and control interventions.

Keywords: African American/Black ancestry, colorectal cancer screening, community-based participatory research, recruitment techniques and strategies

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening saves lives; however, only 60% of the U.S. population aged 50 to 75 is up to date on CRC screening recommendations (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2014; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2008). Compared to other racial and ethnic groups, Blacks experience a disproportionate burden of CRC mortality and are at greatest risk of being overdue for CRC screening (ACS, 2014). To reduce disparities in CRC screening, there is an urgent need to deploy innovative research interventions that increase utilization of the various CRC screening modalities. Unfortunately, interventions promoting CRC screening within an increasingly diverse Black community are limited.

Despite a federal mandate to increase the number of racial–ethnic minorities in research, many studies fail to recruit sufficient numbers (Yancey, Ortega, & Kumanyika, 2006). Obstacles in recruitment include fear and distrust of medical research (Brandon, Isaac, & LaVeist, 2005; Ejiogu et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2008; Knobf et al., 2007; Scharff et al., 2010; Yancey et al., 2006), participant time and financial cost (Doubeni, Laiyemo, Reed, Field, & Fletcher, 2009; Knobf et al., 2007), and lack of awareness about research opportunities (Ford et al., 2008). To overcome these obstacles, researchers must appreciate the increasingly multiethnic U.S. Black population (Consedine, Tuck, Ragin, & Spencer, 2015; Gwede et al., 2011; Gwede, William, et al., 2010), engage with the target community (Knobf et al., 2007), and incorporate culturally-targeted materials and methods (Knobf et al., 2007; Kreuter, Lukwago, Bucholtz, Clark, & Sanders-Thompson, 2003; Yancey et al., 2006).

The implementation of multipronged and varied recruitment techniques in community-based participatory research (CBPR) can help to overcome obstacles and help to ensure successful recruitment into cancer prevention interventions (Ford et al., 2008; Knobf et al., 2007; UyBico, Pavel, & Gross, 2007). CBPR is a collaborative, action-oriented research approach that addresses health disparities through aligning community members’ insider knowledge of their communities with academic researchers’ methodological expertise (Greiner et al., 2014; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). Core values of CBPR include partnership and collaboration between communities and researchers, equitable power distribution, trust and mutual commitment, and openness to knowledge acquired from participant experiences (Israel et al., 2010; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). Recruitment techniques, used with CBPR, can be categorized as active, passive, and snowball. Active recruitment is a proactive technique requiring researchers to identify potential participants through direct solicitation (e.g., in-person intercepts at libraries) (Harris et al., 2003). Passive recruitment is a reactive technique that relies on individuals to contact the research team after coming across study information (e.g., newspaper advertisements) (Harris et al., 2003). Snowball recruitment is a technique whereby enrolled study participants encourage friends and family members to contact the research team (Sadler, Lee, Lim, & Fullerton, 2010).

A multipronged recruitment plan that incorporates the community is increasingly recognized as a successful strategy to recruit diverse populations for research. However, there is a paucity of studies that have investigated the effectiveness of varied recruitment techniques and strategies to increase the participation of ethnically diverse Blacks in cancer disparities research. Most studies do not detail systematic recruitment outcomes, and even fewer report recruitment techniques according to sample characteristics (Yancey et al., 2006). We report on multipronged recruitment techniques, corresponding enrollment efficiency percentages (number of participants enrolled divided by number participants evaluated) (Ellish, Scott, Royak-Schaler, & Higginbotham, 2009; Graham, Lopez-Class, Mueller, Mota, & Mandelblatt, 2011), and lessons learned during recruitment of diverse Black participants to a community-based research study.

Methods

Overview

Increasing Access to Colorectal Cancer Testing for Blacks (I-ACT) is a community-based research study designed to assess the impact of a culturally-targeted, minimal intensity educational intervention on CRC screening using the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) among Blacks in community settings (Christy et al., 2016). Briefly, the I-ACT intervention is based on the preventive health model (PHM) framework that addresses constructs related to cancer screening including susceptibility, salience and coherence of CRC screening, self-efficacy, response efficacy, and barriers (e.g., fear of finding an abnormal result) (Myers et al., 1994; Myers et al., 2007; Vernon, Myers, & Tilley, 1997; Vernon, Myers, Tilley, & Li, 2001). The study sought to recruit a diverse Black population, reflective of the U.S. Black population residing in the Tampa Bay area, to include African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, and those of contemporary African descent (Williams & Jackson, 2000). Prior qualitative research found substantive similarities and minimal differences among a multiethnic Black population, including African American, English-speaking Caribbean, and Haitian blacks living in Tampa Bay area, in their overall perceptions of cancer as well as their attitudes related to barriers, motivation, and resources for CRC screening (Gwede et al., 2011). Findings from this work identified substantial commonalities and overlapping recruitment strategies to reach the subgroups of the Black population in community settings. These shared features support common participant recruitment strategies in the Tampa Bay area to enroll diverse Blacks into a CRC screening intervention. Participants were assigned to one of two study conditions (i.e., intervention or comparison) based on the geographic location of their residence. The intervention condition consisted of a culturally-targeted, low-literacy educational photonovella booklet and culturally-targeted screening reminders, while the comparison condition included the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “Screen for Life” brochure and standard screening reminders (Christy et al., 2016).

All enrolled participants received a free FIT kit at three assessment points (baseline, 12 months, and 24 months). Eligibility included being: (a) between the ages of 50 and 75 years; (b) African American/Black (self-identified); (c) asymptomatic and at average risk for CRC; (d) English speaking; and (e) not up to date on CRC screening. Individuals at increased CRC risk due to having one first-degree relative with CRC diagnosed age <60, >2 first-degree relatives with CRC, or a personal history of CRC, adenomas, or inflammatory bowel disease were not eligible. During eligibility evaluation, recruitment technique, recruitment location, and how participants heard about the study were documented. The University of South Florida Institutional Review Board approved the study. All participants signed written informed consent before participating in any study activities.

Recruitment Techniques and Strategies

Recruitment occurred between October 2011 and August 2014. Multipronged, multicomponent recruitment techniques and strategies were conducted primarily in four contiguous counties of the Tampa Bay area to increase study participation among both foreign-born and U.S.-born Blacks (Consedine et al., 2015; Gwede et al., 2011; Gwede, William, et al., 2010; Read, Emerson, & Tarlov, 2005; U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Initial recruitment began in the county where the cancer center and research team were located. The interstate corridor was used to divide the greater Tampa Bay area into two natural geographic regions (east/west) of comparable population size. After one year, three additional counties were incorporated into the recruitment design to increase study reach, while maintaining the initial east/west geographic schema.

In keeping with the CBPR framework, the research team collaborated with a community advisory board (CAB) composed of stakeholders from the region’s diverse Black community to guide participant recruitment. The CAB suggested the creation of a short testimonial video that would be disseminated through online platforms and during formal presentations. All CAB members had previously assisted with the development of the I-ACT educational intervention materials (Gwede et al., 2011; Gwede, William, et al., 2010). In addition to CAB input, recruitment techniques were identified through literature reviews, previous study experience, and longstanding relationships with community partners (Greiner et al., 2014; Gwede, Menard, et al., 2010). All study-related correspondence and promotional materials (e.g., banners and pens) included an I-ACT study logo that was developed by the research team and CAB. The logo served to create a research study identity to enhance the study’s recognition within the community (Aitken, Gallagher, & Madronio, 2003; Kreuter et al., 2003). The study also had a dedicated website, email, Facebook page, two landlines, and two cell phones.

Active recruitment

Active recruitment included face-to-face contact with community members via three strategies: (a) invited presentations in formal settings; (b) direct intercept in community settings; and (c) attendance at health fairs. Formal presentations of the study were conducted by invitation at churches and community centers. Direct intercepts relied on coordinators to approach potential participants in the community at libraries, state and local public service buildings (e.g., Department of Motor Vehicles), barbershops, and laundromats among others. Coordinators also conducted door-to-door canvassing within neighborhoods that had a percentage of Blacks 50% or greater (based on U.S. Census data). Health fairs took place at a variety of venues, including community centers, churches, and community cultural events (e.g., annual Martin Luther King Jr. festivities).

During active recruitment, the research team set up a table and a large attractive banner with the logo of the cancer center and the I-ACT study logo in a highly visible location at the venue. Black men and women were assessed for potential interest in study participation and screened for age, race, and county of residence. Individuals who passed the initial screening were then evaluated further with detailed, study-specific, eligibility criteria. As part of data collection, the number of people who approached the research team at health fairs and formal presentations, and the number of direct intercepts by the research team was recorded. Coordinators interacted with and gave study-related information to approximately 2,150 individuals utilizing various active recruitment strategies.

Passive recruitment

Passive recruitment (whereby individuals contacted the research team) was implemented via five strategies: (a) flyers, (b) radio and TV spotlights, (c) direct-to-consumer mailing, (d) digital advertisements, and (e) print articles and advertisements. Approximately 5,000 study flyers were distributed at local community establishments such as restaurants, churches, and libraries. An I-ACT study ad ran once on an ethnic radio station and was spotlighted once during a primetime news segment on a mainstream TV station. Digital advertisements for the I-ACT study were featured on Craigslist, Facebook, and Twitter. A link to the I-ACT study website and recruitment video were prominently featured on community partner websites. Print articles were accompanied by a study flyer in local newspapers and magazines that serve the diverse Black community. Direct to consumer mailing included the purchase of a contact list of 10,000 names, mailing addresses, and phone numbers from a national direct mail marketing company. Approximately 2,000 randomly selected adults were mailed a letter to introduce the study, a study flyer, a participation response card, and a self-addressed, prestamped, return envelope.

Passive recruitment entailed asking interested individuals to contact the research team for more information and to be evaluated for study eligibility. Once contacted by potential participants, coordinators explained the I-ACT study, assessed interest, and evaluated study eligibility. As part of data collection, the number of individuals who called the research team and how each individual heard about the study was recorded.

Snowball recruitment

Snowball recruitment was implemented by encouraging enrolled participants to share the I-ACT study flyer/contact information with family members and friends. Potential participants called the research team to determine whether they qualified for the study. The coordinators explained the study, assessed interest, and evaluated study eligibility. All callers were asked how they heard about the study and to provide the name of the person who referred them to the study.

Data Analysis

Within each recruitment technique (active, passive, and snowball), recruitment data were further categorized by strategy and venue. Within this manuscript, technique was defined as the overall recruitment method (active, passive, or snowball). Strategy was defined as the recruitment plan within each recruitment technique (e.g., health fairs within active recruitment technique; flyers within passive recruitment technique). Venue was the location (physical or online) used to recruit participants. To evaluate recruitment effectiveness, enrollment efficiency was calculated for each technique. Enrollment efficiency was defined as a percentage (the number of participants enrolled for each recruitment technique divided by the number of participants evaluated for that particular recruitment technique × 100 (Graham et al., 2011; Lopez et al., 2008). Enrollment efficiency percentages were calculated for each strategy and overall technique. Among enrolled participants, demographic information was summarized using descriptive statistics. The recruitment techniques were mutually exclusive and compared on demographics and enrollment efficiency using the t-test for continuous factors and the Fisher exact test for categorical factors. A nominal alpha of .05 was considered statistically significant (two-tailed).

Results

Participant Characteristics

The three recruitment techniques led to enrollment of 330 participants. Participant characteristics for enrollees are displayed in Table 1. The mean age of enrolled participants was 56.4 years (SD = 5.1) and 52% were men. Sixty percent of participants were unemployed, 57% had health insurance, and 60% had a regular physician. The majority (94%) were born in the U.S. Significant differences in participant demographics were found across recruitment techniques (Table 1). Men were more likely than women to be recruited via snowball and active recruitment (p = .03). Participants with lower education were primarily recruited through snowball recruitment (p = .01). Overwhelmingly, most foreign-born study participants were enrolled in the study by active recruitment (p = .02). Participants with health insurance were more likely to respond to passive and snowball recruitment methods (p = .02). Participants who had a regular personal physician were more likely to respond to passive recruitment methods (p = .01).

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics by Recruitment Technique

| All (N = 330) |

Active (n = 146) |

Passive (n = 129) |

Snowball (n = 55) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Characteristic | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | p |

| Age (years) | 56.4 | (5.1) | 56.1 | (4.9) | 56.4 | (5.4) | 57.2 | (4.7) | .01 |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Gender (male) | 173 | (52.4) | 83 | (56.8) | 56 | (43.4) | 34 | (61.8) | .03 |

| Marital status | .70 | ||||||||

| Married/living with partner | 102 | (30.9) | 47 | (32.2) | 40 | (31.0) | 15 | (27.3) | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 118 | (35.8) | 56 | (38.4) | 44 | (34.1) | 18 | (32.7) | |

| Never married | 110 | (33.3) | 43 | (29.5) | 45 | (34.9) | 22 | (40.0) | |

| Education (≤ high school diploma)a | 167 | (50.6) | 71 | (48.6) | 58 | (45.0) | 38 | (69.1) | .01 |

| Employment (employed) | 132 | (40.0) | 60 | (41.1) | 55 | (42.6) | 17 | (30.9) | .30 |

| Ethnicity (Non-Hispanic) | 321 | (97.3) | 143 | (97.9) | 124 | (96.1) | 54 | (98.2) | .70 |

| Country of origin | |||||||||

| US-born | 310 | (93.9) | 131 | (89.7) | 125 | (96.9) | 54 | (98.2) | .02c |

| US-born, multigenerational | 303 | (97.7) | 127 | (96.9) | 122 | (97.6) | 54 | (100.0) | |

| US-born, first-generationb | 7 | (2.3) | 4 | (3.1) | 3 | (2.4) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Foreign-born | 20 | (6.1) | 15 | (10.3) | 4 | (3.1) | 1 | (1.8) | |

| African | 4 | (20.0) | 4 | (26.7) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Caribbean | 15 | (75.0) | 10 | (66.7) | 4 | (100.0) | 1 | (100.0) | |

| Central American | 1 | (5.0) | 1 | (6.7) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Health insurance (yes) | 187 | (56.7) | 72 | (49.3) | 77 | (59.7) | 38 | (69.1) | .03 |

| Regular personal physician (yes) | 196 | (59.6) | 74 | (50.7) | 89 | (69.0) | 33 | (61.1) | .01 |

| Family history, any cancer (yes)d | 150 | (45.5) | 62 | (42.5) | 60 | (46.5) | 28 | (50.9) | .64 |

Alternative is at least some college.

At least one parent is foreign-born.

p-value determined between US-born and foreign-born.

First-degree relative.

Recruitment Reach by Recruitment Technique

The reach of the I-ACT study to evaluate potential participants varied widely by recruitment technique (Figure 1). Five hundred and sixty individuals were evaluated for eligibility. Among the 560 individuals evaluated for eligibility, 262 (46.8%) were recruited actively, 222 (39.6%) were recruited passively, and 76 (13.6%) recruited via snowball. Among those evaluated, 395 (70.5%) were eligible for participation. Among evaluated participants, snowball recruitment technique led to the largest proportion of eligible participants (77.6%).

FIGURE 1.

I-ACT enrollment yield by recruitment technique.

Enrollment Efficiency by Recruitment Technique and Strategy

Three hundred and thirty participants enrolled in the study, 58.9% of those who were evaluated. Participant enrollment varied by recruitment technique. Active recruitment accounted for the highest number of enrolled participants, followed by passive, and, finally, snowball. To compare recruitment techniques, enrollment efficiencies were calculated. At 72.4%, snowball had the highest enrollment efficiency. The enrollment efficiency for active and passive recruitment was 55.7% and 58.1%, respectively.

Enrollment efficiency for each active recruitment strategy was calculated (Table 2). Direct intercepts had the greatest enrollment efficiency (58.8%), followed by health fairs (54.1%), and formal presentations (47.0%). Direct intercepts at barbershops and laundromats had the very high enrollment efficiencies (100%); however, only three participants were enrolled in the study at these locations. Conversely, direct intercepts at libraries had an enrollment efficiency of 60%, but led to 45 enrolled participants. Enrollment efficiency for each passive recruitment strategy was calculated (Table 2). Digital ads had the greatest enrollment efficiency (69%), followed by print articles and ads (60.5%), radio and TV spotlights (60%), direct mailing (57.6%), and flyers (48.7%). Among digital ads, Craigslist had an enrollment efficiency (72.7%). Print articles and ads had an enrollment efficiency of 60.5%, but led to 63 enrolled participants.

TABLE 2.

Active and Passive Recruitment Enrollment Efficiencies by Strategy and Venue

| Type/strategy/venue | Evaluated | Eligible | Enrolled | EE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | ||||

| Formal Presentations | ||||

| Church | 13 | 7 | 5 | 38.4 |

| Community center | 4 | 3 | 3 | 75.0 |

| Total | 17 | 10 | 8 | 47.0 |

| Direct Intercepts | ||||

| Barbershop | 2 | 2 | 2 | 100.0 |

| Canvasing | 7 | 2 | 2 | 28.5 |

| Community center | 25 | 23 | 19 | 76.0 |

| DMV | 10 | 7 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Laundromat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| Libraries | 75 | 57 | 45 | 60.0 |

| Store | 4 | 3 | 1 | 25.0 |

| Total | 124 | 95 | 73 | 58.8 |

| Health fairs | ||||

| Church | 38 | 23 | 13 | 34.2 |

| City/state building | 13 | 7 | 6 | 46.1 |

| Civic organizations | 18 | 8 | 8 | 44.4 |

| Community Center | 10 | 10 | 6 | 60.0 |

| Corporations | 3 | 3 | 3 | 100.0 |

| University/hospital | 39 | 34 | 29 | 74.3 |

| Total | 121 | 85 | 65 | 54.1 |

| Active (grand total) | 262 | 190 | 146 | 55.7 |

| Passive | ||||

| Flyers | 41 | 25 | 20 | 48.7 |

| Radio and TV spotlights | 5 | 3 | 3 | 60.0 |

| Direct mail | 59 | 39 | 34 | 57.6 |

| Digital ads | ||||

| Internet ad (e.g., Craigslist) | 11 | 9 | 8 | 72.7 |

| List serve | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| Social media (e.g., Facebook) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I-ACT study website | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 13 | 10 | 9 | 69.0 |

| Print articles and ads | ||||

| Newspaper | 100 | 68 | 62 | 62.0 |

| Cultural magazines | 4 | 1 | 1 | 25.0 |

| Total | 104 | 69 | 63 | 60.5 |

| Passive (grand total) | 222 | 146 | 129 | 58.1 |

Note. N = . DMV = Department of Motor Vehicles; EE = enrollment efficiency (participants enrolled/ participants evaluated * 100); I-ACT = Increasing Access to Colorectal Cancer Testing for Blacks.

Reasons for Nonparticipation

Overall, 165 (29.5%) of those evaluated were ineligible to participate in this study. Most participants were excluded because of self-report of being up to date on CRC screening (50.3%), followed by a personal history of CRC or other cancer (20.0%). Individuals recruited actively were more likely to be excluded due to being up to date on CRC screening. Passively recruited individuals were more likely to be excluded due to a personal history of cancer.

Discussion

This analysis sought to detail the contributions of various recruitment techniques and strategies to enroll ethnically-diverse Blacks to a community-based research study to increase CRC screening. Similar to other community-based studies (Lopez et al., 2008; Wilbur et al., 2006), we found that a combination of recruitment techniques and strategies contributed toward the successful enrollment of 330 participants. The importance of diverse Black participants in health disparities research has been well established (Yancey et al., 2006), and the successful recruitment of Blacks into this intervention contributes to reduction of CRC screening disparities.

Among all of the recruitment techniques utilized in this intervention, active enrollment resulted in the highest number of enrolled participants. The “boots on the ground” approach of active recruitment allowed the research team—with the help of the CAB—to cast a wide net and interact with approximately 2,150 community members. Active recruitment is often the primary technique for recruiting racial/ethnic minority populations, as it often directly addresses recruitment barriers (Graham et al., 2011; Lopez et al., 2008; Nicholson et al., 2011; UyBico et al., 2007; Yancey et al., 2006). Although resource-intensive, active recruitment within the I-ACT study led to the establishment of an ongoing relationship with the community that fostered communication, trust, and respect. Coordinators engaged potential participants in meaningful reciprocal interactions (e.g., answer questions and ease fears) that likely contributed to the study’s successful recruitment efforts. Attributes of study coordinators are important in working with any population, but are particularly important when working with ethnically-diverse Blacks.

Despite active recruitment resulting in the highest number of enrolled participants, it had the lowest enrollment efficiency among the three recruitment techniques. Lower active recruitment enrollment efficiency may be due to inherently poor precision of the methods of identifying potentially eligible individuals. During face-to-face recruitment, minority concordant (primarily Black) coordinators approached men and women that “appeared to be” 50 years and older or “appeared to be” Black. However, to minimize this potential bias, every prospective participant was asked age and racial identity screening questions.

Similar to other studies, passive and snowball recruitment had higher enrollment efficiency than active recruitment (Graham et al., 2011; Harris et al., 2003). The higher enrollment efficiency of passive recruitment methods is perhaps due to the opportunity to widely distribute study information to potential participants by listing broad study criteria and allowing participants to gauge their potential eligibility prior to a discussion with the study team. Snowball recruitment had the highest enrollment efficiency. This may be because a recommendation by a family member or friend helps to promote trust and reduce the fear, anxiety, and stress related to participating in research studies (Rodriguez, Rodriguez, & Davis, 2006; Sadler et al., 2010). Thus, snowball recruitment is a technique that may be particularly effective in populations who have a turbid historical relationship with research and medical science (Sadler et al., 2010). The drawback to snowball recruitment is that it does not recruit a random or representative sample; participants are more likely to recommend the study to friends and family members who are similar to themselves (Sadler et al., 2010).

Consistent with published literature, we found associations between method of recruitment and select demographics. Participants enrolled through snowball recruitment were more likely to be male (Jones, Steeves, & Williams, 2009) and have lower educational attainment (Sadler et al., 2010). Participants enrolled through passive recruitment were more likely to be female (Wilbur et al., 2006) and have a regular physician (Ellis, Butow, Tattersall, Dunn, & Houssami, 2001). Active recruitment was associated with greater likelihood of enrolling males (Ellish et al., 2009) and foreign-born participants (UyBico et al., 2007; Yancey et al., 2006). Foreign-born participants were more likely to be reached by active methods because it allowed researchers to find and approach them at events, locations, and times that were familiar to the participants, thus minimizing the cultural and contextual barriers to recruitment which have been widely reported in other studies (Rodriguez et al., 2006; UyBico et al., 2007; Yancey et al., 2006).

Community Advisory Board

Utilization of diverse recruitment techniques led to the successful enrollment of 330 Black men and women. The study’s CAB aided in the development of the recruitment plan and infused “real world” and practical perspectives to reaching a diverse population of Blacks. Discussions with the CAB led to the initialization of recruitment strategies geared toward the subpopulations within the diverse Black community. Participant enrollment within this intervention highlight that when planning recruitment activities, the importance of efficiency versus reach must be predicated on the population, type of research underway, recruitment goals, and input from the community. In Table 3, we summarize key lessons learned, advantages, and disadvantages for selected examples from the recruitment techniques. The array of recruitment techniques and strategies provides an important methodological backdrop for the conduct of community-based research to reduce racial disparities in the unequal burden of CRC.

TABLE 3.

Recruitment Technique Lessons Learned

| Technique/strategies | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| Active | ||

| Community presentation |

|

|

| Door-to-door, direct intercepts |

|

|

| Passive | ||

| Print (newspaper, radio ads) |

|

|

| Direct mail |

|

|

| Flyers |

|

|

| Digital media |

|

|

| Snowball | ||

| Enrolled participants recruit |

|

|

Strengths and Limitations

Our study included a number of strengths that may have contributed to our high study enrollment. First, we employed convenient and flexible interview times and locations. Coordinators also provided phone, mailed, and e-mailed reminders to confirm participant appointments. Second, the research team was diverse in terms of racial/ethnic background and gender which may have added a level of trust for community members (Ellish et al., 2009). Third, culturally interesting and engaging components included in recruitment materials (e.g., country flags and photos of diverse Blacks on flyers, testimony of other participants in newspaper ads, etc.) may have promoted interest in the study (Ford et al., 2008; Greiner et al., 2014; Kreuter et al., 2003; Yancey et al., 2006). Fourth, recruitment efforts involved feedback and interactions with a study-specific CAB and close partnerships with community stakeholders to guide study recruitment efforts, provide a visible community presence, and help to communicate the immediate benefits of research to community members (Greiner et al., 2014; Gwede, Menard, et al., 2010; Yancey et al., 2006). Fifth, the design of the study and the gradual incorporation of additional recruitment counties, community locations, and recruitment strategies allowed us to determine the unique contribution of each recruitment strategy in isolation, and critical parameters were tracked to calculate enrollment efficiency. Methods that were deemed unproductive (e.g., door-to-door canvassing, direct mailing) were dropped after it became evident these methods were not producing meaningful enrollment yields. Hence, the research team concentrated efforts on methods that had either high enrollment efficiency or that yielded a high number of enrollment overall.

Study limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample had a diverse range of education levels, health insurance, and regular source of medical care. As a result, our results may not be generalizable to Black populations in other regions of the country where socioeconomic, educational level, and ethnic subgroup mix may substantially differ. Second, contact hours and time spent on all recruitment strategies were not systematically recorded, and, thus, we were unable to quantitatively determine time and cost associated with specific recruitment techniques and strategies. Third, it was challenging to document the reach for radio, TV, newspapers, and flyers. Nevertheless, the wide reach of these initiatives contributed to high study enrollment. Fourth, the effects of recruitment technique on the intervention treatment effect is a potential concern. However, it was anticipated that participant randomization mitigated potential any bias introduced via recruitment.

Conclusion

Achieving health equity, eliminating disparities, and improving the health of all population groups is a public health mandate. In our study, we had success recruiting and enrolling Black men and women (who are typically underrepresented) to participate in a randomized control intervention to increase CRC screening. Although we had great success recruiting ethnically-diverse Black participants, overall enrollment of Blacks into cancer screening studies—in particular, CRC—is low. The final sample size (given the resources and effort) is in part a reflection of the challenges of recruiting and enrolling participants in longitudinal intervention research in underserved settings. If researchers are going to improve cancer outcomes and provide culturally effective care, researchers must increase their reach toward ethnically-diverse populations through multipronged approaches. Future research should examine whether multipronged approaches that require resources and effort can boost enrollment and participation of larger numbers of Blacks, and whether such community-based recruitment strategies are effective in other racial/ethnic minority populations that are underrepresented in CRC screening interventions. Enrollment success indicates that a study steeped in the community leads to better recruitment of potential participants and high enrollment efficiency. Traditional obstacles to recruitment may vary by individual and community, however, these obstacles can be overcome by incorporating cultural appropriate strategies, incorporating community input from the very start of intervention development, and effective communication with the target population.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the study was funded by Research Scholar Grant Award RSGT-11-012-01-CPPB (PI: C.K. Gwede) from the American Cancer Society. The work of the first and fifth authors were funded by R25CA090314-12 (PI: P.B. Jacobsen) from the National Cancer Institute at the NIH. The work conducted was also supported by the Biostatistics Core and the Survey Methods Core at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (NIH/NCI Grant Number: P30-CA076292).

This paper was accepted under the Editorship of Susan J. Henly.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Conduct of Research: The authors of this manuscript together have abided by the ethical conduct of research. This research was approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

Contributor Information

Stacy N. Davis, Rutgers University, School of Public Health, Piscataway, NJ.

Swapamthi Govindaraju, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL.

Brittany Jackson, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL.

Kimberly R. Williams, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL.

Shannon M. Christy, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN.

Susan T. Vadaparampil, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL; University of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa, FL.

Gwendolyn P. Quinn, New York University Medical Center, New York, NY.

David Shibata, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN.

Richard Roetzheim, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL; University of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa, FL.

Cathy D. Meade, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL; University of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa, FL.

Clement K. Gwede, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL; University of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa, FL.

References

- Aitken L, Gallagher R, Madronio C. Principles of recruitment and retention in clinical trials. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2003;9:338–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures: 2014–2016. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2014. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2014-2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon DT, Isaac LA, LaVeist TA. The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: Is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97:951–956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christy SM, Davis SN, Williams KR, Zhao X, Govindaraju SK, Quinn GP, Gwede CK. A community-based trial of educational interventions with fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer screening uptake among blacks in community settings. Cancer. 2016;122:3288–3296. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Tuck NL, Ragin CR, Spencer BA. Beyond the black box: A systematic review of breast, prostate, colorectal, and cervical screening among native and immigrant African-descent Caribbean populations. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2015;17:905–924. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-9991-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Reed G, Field TS, Fletcher RH. Socioeconomic and racial patterns of colorectal cancer screening among Medicare enrollees in 2000 to 2005. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009;18:2170–2175. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejiogu N, Norbeck JH, Mason MA, Cromwell BC, Zonderman AB, Evans MK. Recruitment and retention strategies for minority or poor clinical research participants: Lessons from the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Life Span study. Gerontologist. 2011;51:S33–S45. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis PM, Butow PN, Tattersall MHN, Dunn SM, Houssami N. Randomized clinical trials in oncology: Understanding and attitudes predict willingness to participate. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:3554–3561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellish NJ, Scott D, Royak-Schaler R, Higginbotham EJ. Community-based strategies for recruiting older, African Americans into a behavioral intervention study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2009;101:1104–1111. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31105-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, Gibbons MC, Bass EB. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112:228–242. doi: 10.1002/Cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham AL, Lopez-Class M, Mueller NT, Mota G, Mandelblatt J. Efficiency and cost-effectiveness of recruitment methods for male Latino smokers. Health Education & Behavior. 2011;38:293–300. doi: 10.1177/1090198110372879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner KA, Friedman DB, Adams SA, Gwede CK, Cupertino P, Engelman KK, Hébert JR. Effective recruitment strategies and community-based participatory research: Community networks program centers’ recruitment in cancer prevention studies. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2014;23:416–423. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwede CK, Jean-Francois E, Quinn GP, Wilson S, Tarver WL, Thomas KB, Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network, partners Perceptions of colorectal cancer among three ethnic subgroups of US blacks: A qualitative study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011;103:669–680. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwede CK, Menard JM, Martinez-Tyson D, Lee JH, Vadaparampil ST, Padhya TA, Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network Community, Partners Strategies for assessing community challenges and strengths for cancer disparities participatory research and outreach. Health Promotion Practice. 2010;11:876–887. doi: 10.1177/1524839909335803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwede CK, William CM, Thomas KB, Tarver WL, Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, Meade CD. Exploring disparities and variability in perceptions and self-reported colorectal cancer screening among three ethnic subgroups of U.S. Blacks. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2010;37:581–591. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.581-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KJ, Ahluwalia JS, Catley D, Okuyemi KS, Mayo MS, Resnicow K. Successful recruitment of minorities into clinical trials: The Kick It at Swope project. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:575–584. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000118540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Schulz AJ, McGranaghan RJ, Lichtenstein R, Burris A. Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA, Steeves R, Williams I. Strategies for recruiting African American men into prostate cancer screening studies. Nursing Research. 2009;58:452–456. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181b4bade. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobf MT, Juarez G, Lee SYK, Sun V, Sun Y, Haozous E. Challenges and strategies in recruitment of ethnically diverse populations for cancer nursing research. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34:1187–1194. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.1187-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz RD, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: Targeted and tailored approaches. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30:133–146. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez EN, Simmons VN, Quinn GP, Meade CD, Chirikos TN, Brandon TH. Clinical trials and tribulations: Lessons learned from recruiting pregnant ex-smokers for relapse prevention. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:87–96. doi: 10.1080/14622200701704962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers RE, Ross E, Jepson C, Wolf T, Balshem A, Millner L, Leventhal H. Modeling adherence to colorectal cancer screening. Preventive Medicine. 1994;23:142–151. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers RE, Sifri R, Hyslop T, Rosenthal M, Vernon SW, Cocroft J, Wender R. A randomized controlled trial of the impact of targeted and tailored interventions on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer. 2007;110:2083–2091. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson LM, Schwirian PM, Klein EG, Skybo T, Murray-Johnson L, Eneli I, Groner JA. Recruitment and retention strategies in longitudinal clinical studies with low-income populations. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2011;32:353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JG, Emerson MO, Tarlov AJ. Implications of black immigrant health for U.S. racial disparities in health. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2005;7:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s10903-005-3677-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez MD, Rodríguez J, Davis M. Recruitment of first-generation Latinos in a rural community: The essential nature of personal contact. Family Process. 2006;45:87–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler GR, Lee HC, Lim RS, Fullerton J. Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2010;12:369–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: Understanding mistrust about research participation. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21:879–897. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey: The Foreign-Born Population in the United States: 2010. (ACS-19) Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2012/acs/acs-19.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;149:627–637. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UyBico SJ, Pavel S, Gross CP. Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: A systematic review of recruitment interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:852–863. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0126-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon SW, Myers RE, Tilley BC. Development and validation of an instrument to measure factors related to colorectal cancer screening adherence. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 1997;6:825–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon SW, Myers RE, Tilley BC, Li S. Factors associated with perceived risk in automotive employees at increased risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2001;10:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur J, McDevitt J, Wang E, Dancy B, Briller J, Ingram D, Zenk SN. Recruitment of African American women to a walking program: Eligibility, ineligibility, and attrition during screening. Research in Nursing & Health. 2006;29:176–189. doi: 10.1002/nur.20136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Jackson JS. Race/ethnicity and the 2000 census: Recommendations for African American and other black populations in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1728–1730. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]