Abstract

A family of 11 cell surface-associated aspartyl proteases (CgYps1–11), also referred as yapsins, is a key virulence factor in the pathogenic yeast Candida glabrata. However, the mechanism by which CgYapsins modulate immune response and facilitate survival in the mammalian host remains to be identified. Here, using RNA-Seq analysis, we report that genes involved in cell wall metabolism are differentially regulated in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant. Consistently, the mutant contained lower β-glucan and mannan levels and exhibited increased chitin content in the cell wall. As cell wall components are known to regulate the innate immune response, we next determined the macrophage transcriptional response to C. glabrata infection and observed differential expression of genes implicated in inflammation, chemotaxis, ion transport, and the tumor necrosis factor signaling cascade. Importantly, the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant evoked a different immune response, resulting in an enhanced release of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β in THP-1 macrophages. Further, Cgyps1–11Δ–induced IL-1β production adversely affected intracellular proliferation of co-infected WT cells and depended on activation of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) signaling in the host cells. Accordingly, the Syk inhibitor R406 augmented intracellular survival of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant. Finally, we demonstrate that C. glabrata infection triggers elevated IL-1β production in mouse organs and that the CgYPS genes are required for organ colonization and dissemination in the murine model of systemic infection. Altogether, our results uncover the basis for macrophage-mediated killing of Cgyps1–11Δ cells and provide the first evidence that aspartyl proteases in C. glabrata are required for suppression of IL-1β production in macrophages.

Keywords: cell wall, chemotaxis, interleukin 1 (IL-1), macrophage, spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), Yapsins, cell wall remodeling, mouse organ colonization, IL-1beta, Syk, THP-1 macrophages, intracellular survival

Introduction

Hospital-acquired invasive mycoses pose an enormous health and economic challenge and account for 10% of all nosocomial bloodstream infections (BSIs)4 worldwide (1, 2). Candida species, benign residents of mucosal surfaces and the gut in healthy individuals, are the fourth most common bloodstream pathogens (1–3). Among Candida spp., Candida albicans is the predominant species responsible for 60% of BSIs (1, 2). However, recent global surveillance programs have revealed a substantial shift in the epidemiology of systemic candidiasis to non-albicans species (1–3). Prevalence of C. glabrata, a haploid budding yeast, varies geographically, ranges from second to fourth, and accounts for up to 30% of Candida BSIs (2–5).

Phylogenetically, C. glabrata is more closely related to the nonpathogenic yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae than to other pathogenic Candida spp. and belongs to the Saccharomyces clade (5, 6). Accordingly, the ability of C. glabrata to survive in and adapt to multiple host microenvironments is presumed to emerge independently from that of other Candida species (6). C. glabrata lacks mating and true hyphae formation and induces no mortality in immunocompetent mice in the systemic candidiasis model (5–7). However, it is able to adhere to biotic and abiotic surfaces via a family of cell wall adhesins, possesses a family of 11 glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked aspartyl proteases, and shows high intrinsic resistance to diverse stresses and azole antifungal drugs (5, 7, 8).

Using macrophage culture and murine models, it has previously been demonstrated that C. glabrata is able to proliferate in macrophage cells in vitro and evade host immune killing in vivo (7, 9–11). In macrophages, C. glabrata has been shown to interfere with the phagosomal maturation process, cytokine production, and reactive oxygen species generation (9, 10, 12). Induction of autophagy and transcriptional reprogramming of metabolic genes to survive the nutrient-poor macrophage environment and remodeling of its chromatin architecture to encounter DNA damage stress are known strategies that C. glabrata employs to replicate in macrophages (12, 13).

Among known virulence factors of C. glabrata, a family of 11 putative GPI-linked, cell surface-associated aspartyl proteases occupies a central position (7, 9). These proteases, also referred as yapsins, are encoded by CgYPS1–11 genes. Of these, eight CgYPS genes (CgYPS3–6 and CgYPS8–11) are encoded in a unique cluster on chromosome E (9). CgYPS genes show structural similarity to five YPS genes (YPS1–3, YPS6, and YPS7) present in S. cerevisiae (9, 14). Unlike most aspartyl proteases, which cleave at hydrophobic residues, yapsins have a common specificity for basic amino acid residues (14, 15).

Of the 11 CgYPS genes, seven (CgYPS2, CgYPS4–5, and CgYPS8–11) are up-regulated in response to internalization by macrophages (9). Accordingly, CgYapsins have been implicated in survival of C. glabrata in macrophages, cell wall remodeling, activation of macrophages through nitric oxide generation, and virulence in both a systemic model of candidiasis and a minihost model of Drosophila melanogaster (9, 12, 16, 17). The role of CgYapsins in cell wall homeostasis has been attributed in part to the removal and release of GPI-anchored cell wall proteins (9). In addition, CgYapsins have been implicated in proper functioning of the vacuole (16), with CgYps1 also uniquely required for intracellular pH homeostasis (18).

Because survival of C. glabrata in the host largely relies on an immune evasion mechanism (19) and CgYapsins are essential for its virulence (9), we, here, have examined their biological functions via a combined approach of gene disruption, transcriptional, and immunological analyses. Using human THP-1 macrophages, we show that the putative catalytic aspartate residue of CgYps1 is critical for intracellular survival and proliferation of C. glabrata. Our data implicate CgYps4, -5, -8, and -10 for the first time in survival of the macrophage internal milieu. Last, we demonstrate that CgYapsins are required for inhibition of Syk signaling–dependent production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-1β in macrophages and for organ colonization and dissemination during systemic infections of mice.

Results

RNA-Seq analysis reveals up-regulation of cell wall organization genes in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant

The Cgyps1–11Δ mutant, which lacks all 11 CgYapsins, is known to display pleiotropic defects, including increased susceptibility to cell wall and osmotic stress, perturbed vacuole and pH homeostasis, and attenuated intracellular survival and pathogenesis (9, 16, 18). Hence, to investigate whether lack of CgYapsins affects gene regulation at the transcriptional level, we performed global transcriptome profiling of YPD-grown log-phase WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cells using the RNA-Seq approach. We found a total of 124 genes to be differentially expressed (≥1.5-fold change and a false discovery rate–adjusted p value of ≤0.05) in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant (Table S1). Of these, 89 and 35 genes were up-regulated and down-regulated, respectively (Table S1). Gene ontology (GO)-Slim Mapper analysis, using the Candida Genome Database (www.candidagenome.org),5 revealed genes involved in biological processes of “transport,” “response to stress,” “carbohydrate metabolic process,” and “cell wall organization” to be differentially expressed in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant.

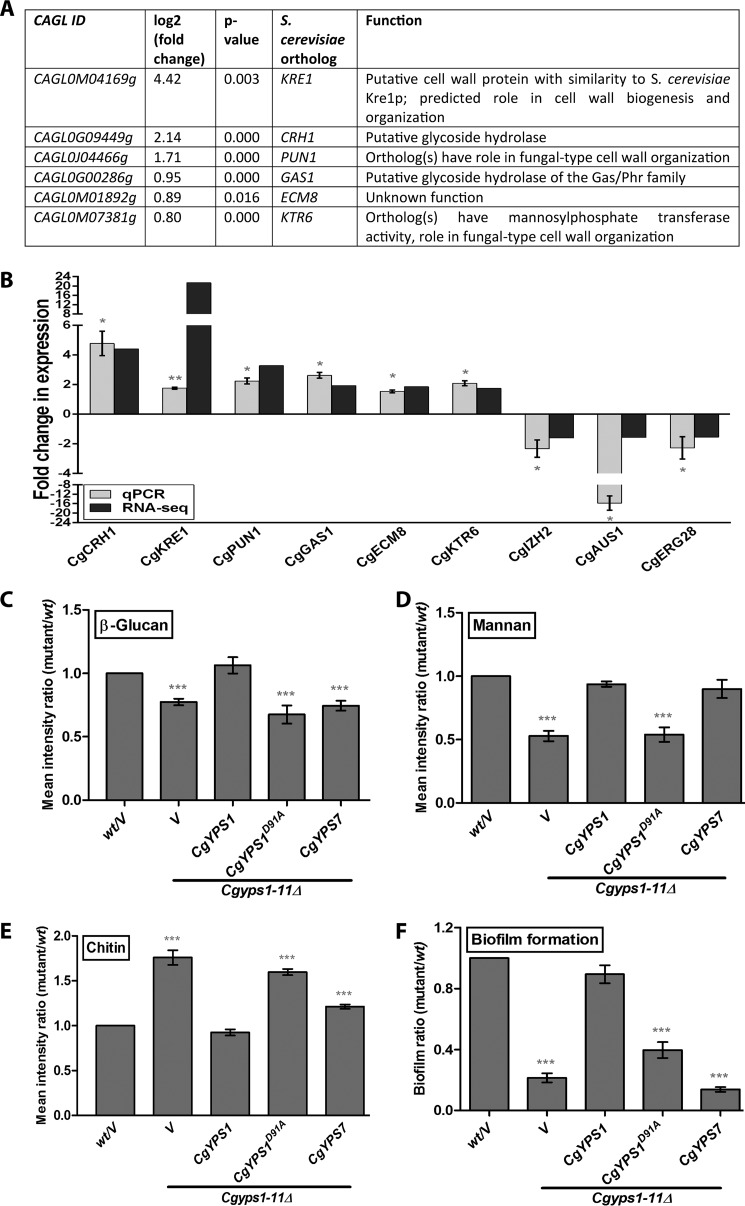

To identify significantly enriched GO terms, classified according to biological process annotations, in differentially expressed genes (DEGs), we employed DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery; https://david.ncifcrf.gov)5 (20, 21) and the FungiFun2 tool (https://elbe.hki-jena.de/fungifun/fungifun.php)5 (22). GO categories ion transport (GO:0006811; p = 0.0002) and oxidation-reduction process (GO:0055114; p = 0.0002) were enriched in the down-regulated gene list, and carbohydrate metabolic process (GO:0005975; p = 0.0001) was enriched in the up-regulated gene set in the FungiFun2 analysis. GO terms fungal-type cell wall organization (GO:0031505; p = 0.0047) and tricarboxylic acid cycle (GO:0006099; p = 0.047) were enriched in the up-regulated gene list, and the GO term sterol import (GO:0035376; p = 0.0.030) was enriched in the down-regulated gene set in the DAVID analysis. Fungal cell wall organization genes that are differentially expressed in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant are shown in Fig. 1A.

Figure 1.

RNA-Seq analysis reveals genes involved in polysaccharide metabolism to be up-regulated in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant. A, list of differentially expressed genes that belong to the GO term “fungal-type cell wall organization” (GO:0031505), in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant. B, qPCR validation of the RNA-Seq data. RNA was extracted, using the acid phenol extraction method, from log-phase WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cultures, and transcript levels of the indicated genes (six up-regulated and three down-regulated in the RNA-Seq experiment) were measured by qPCR. Data (mean ± S.E. (error bars), n = 3–4) were normalized against the CgACT1 mRNA control and represent -fold change in expression in Cgyps1–11Δ mutant compared with the WT strain. *, p < 0.05, paired two-tailed Student's t test. C–E, flow cytometry–based cell wall polysaccharide measurement. Indicated log-phase C. glabrata strains were harvested and stained with aniline blue, FITC-concanavalin A, and calcofluor white to estimate cell wall β-glucan (C), mannan (D), and chitin (E) content, respectively. Data (mean ± S.E., n = 3–7) presented as the mean fluorescence intensity ratio were calculated by dividing the fluorescence intensity value of the mutant sample by that of the WT sample (set as 1.0). V, C. glabrata strains carrying empty vector. ***, p < 0.001; paired two-tailed Student's t test. F, assessment of biofilm-forming capacity of the indicated C. glabrata strains on polystyrene-coated plates through a crystal violet–based staining assay. YPD-grown log-phase cells were suspended in PBS, and 1 × 107 cells were incubated at 37 °C for 90 min in a polystyrene-coated 24-well plate. After two PBS washes, RPMI medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum was added to each well. Cells were allowed to make biofilms at 37 °C with shaking (75 rpm) for 48 h, with replacement of half of the spent RPMI medium with the fresh medium after 24 h of incubation. Following the removal of unbound C. glabrata cells with three PBS washes, the plate was air-dried and incubated with 250 μl of crystal violet solution (0.4% in 20% ethanol). After 45 min, 95% ethanol was added to stained adherent C. glabrata cells, and absorbance of the destaining solution was recorded at 595 nm after 45 min. The biofilm ratio was calculated by dividing the mutant absorbance units by those of WT cells (set to 1.0). Data represent mean ± S.E. of 4–7 independent experiments. V, C. glabrata strains carrying empty vector. ***, p < 0.001; paired two-tailed Student's t test.

We next verified the RNA-Seq gene expression data by quantitative real time-PCR (qPCR) analysis and found a good correlation in expression levels between RNA-Seq and qPCR data for six up-regulated (CgCRH1, CgKRE1, CgPUN1, CgGAS1, CgECM8, and CgKTR6) and three down-regulated (CgIZH2, CgAUS1, and CgERG28) tested genes (Fig. 1B). Of note, CgCRH1, CgAUS1, CgERG28, and CgIZH2 genes code for a putative glycoside hydrolase, sterol transporter, ergosterol biosynthetic protein, and cellular zinc ion homeostatic protein, respectively.

As the Cgyps1Δ mutant has previously been shown to display metal ion sensitivity and perturbed pH homeostasis (16, 18), differential expression of genes involved in the oxidation-reduction process and ion transport in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant may be attributed to the role of CgYps1 in maintenance of intracellular pH and ion homeostasis. Further, sunken cell wall and constitutively active protein kinase C–mediated cell wall integrity pathway have previously been reported in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant (16). Thus, our expression profiling data with up-regulation of genes implicated in fungal cell wall organization are consistent with a requirement for CgYapsins for maintenance of the cell wall architecture.

The highly cross-linked fungal cell wall is a dynamic structure that undergoes significant remodeling in response to environmental cues (23). To examine the role of CgYapsins in cell wall homeostasis more closely, we sought to measure levels of cell wall polysaccharides, β-glucan, mannan, and chitin, which account for >90% of the C. glabrata cell wall (23), in WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cells. Aniline blue–based staining of β-glucan revealed that compared with the WT strain, the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant contains 30% lower levels of β-glucan under log-phase conditions (Fig. 1C). As in vitro phenotypes of Cgyps1Δ7Δ and Cgyps1–11Δ mutants have been reported to be largely similar (9, 16), we next checked CgYps1- and CgYps7-mediated complementation of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant defects. Ectopic expression of CgYPS1 but not of CgYPS7 could restore β-glucan content to WT levels (Fig. 1C). These results implicate CgYps1 in glucan homeostasis. Similarly, cell wall mannan content, as determined by fluorescence measurement of FITC-labeled concanavalin A-stained cells, was found to be 2-fold lower in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant (Fig. 1D). This defect was rescued fully by ectopic expression of either CgYPS1 or CgYPS7 (Fig. 1D). In contrast, calcofluor white-based staining of cell wall chitin showed 1.8-fold higher chitin content in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant, compared with WT cells (Fig. 1E). Importantly, elevated chitin levels in the mutant were fully and partially rescued by expression of CgYPS1 and CgYPS7, respectively (Fig. 1E), indicating a role for both CgYps1 and CgYps7 in maintenance of the cell wall chitin content. Together, these data indicate that CgYapsins are required for cell wall homeostasis with a unique requirement of CgYps1 for maintenance of β-glucan content and of CgYps1 and CgYps7 for sustainment of chitin and mannan levels.

Cell wall is the first point of contact between C. glabrata cells and the external surface. To investigate whether altered cell wall composition of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant modulates its interaction with abiotic surfaces, we next measured the ability of the mutant to form biofilm on polystyrene-coated microtiter plates. We found that the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant was severely compromised in biofilm formation on polystyrene, and CgYPS1 expression could fully complement this defect (Fig. 1F). These results are suggestive of a specific requirement for CgYps1 in biofilm formation and raise the possibility of a nexus between cell wall β-glucan content and the capacity to form biofilm in C. glabrata.

Overall, our RNA-Seq and biochemical analysis are demonstrative of an altered cell wall composition of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant, which could largely be attributed to the lack of CgYps1 and CgYps7 enzymes. Furthermore, an explicit function of CgYapsins in cell wall organization is consistent with previous reports (9, 16) as well as with reported roles for yapsins in S. cerevisiae (14, 15), indicating functional similarity between aspartyl proteases of these two yeasts.

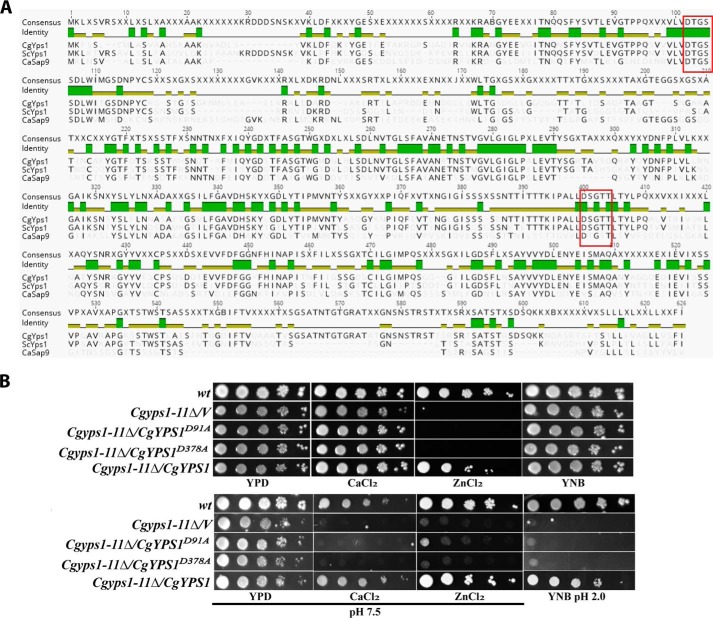

Predicted catalytic aspartate residues of CgYps1 are essential for its functions in cell physiology

CgYps1 and CgYps7 are putative GPI-anchored cell wall proteases that contain an N-terminal signal peptide, a pro-peptide region, two catalytic domains, a conserved C-terminal region, and a GPI signal at the C terminus (15). These are assumed to undergo proteolytic cleavage with the mature enzyme consisting of α and β subunits, with each subunit contributing one catalytic aspartate residue (15). Although mutants lacking these enzymes displayed cell wall defects (9, 16), the observed defects could presumably be due to the lack of these proteins in the cell wall leading to an altered cell wall structure. Hence, to examine whether presence or the catalytic activity of CgYps1 and CgYps7 is required for cell wall metabolism, we sought to identify and mutate conserved aspartic acid residues in both enzymes. It is worth noting that the Cgyps7Δ mutant has previously been shown to be sensitive to cell wall stressors (9). Multiple-protein sequence alignment of C. glabrata Yps1, S. cerevisiae Yps1, and C. albicans Sap9 (CaYps1) revealed two potential catalytic aspartate residues at positions 91 and 378 in the 601-amino acid-long CgYps1 enzyme (Fig. 2A). However, multiple-protein sequence alignment of CgYps7 with S. cerevisiae yapsins, including ScYps7, and C. albicans Saps, including Sap10, did not identify any conserved catalytic aspartate residues in the CgYps7 enzyme. Hence, we decided to mutate the predicted catalytic aspartate residues at positions 91 and 378 in CgYps1 only.

Figure 2.

Predicted catalytic residues of CgYps1 are required for its functions. A, multiple protein sequence alignment of Yps1. The sequences of Yps1 from C. glabrata (Cagl0m04191p), S. cerevisiae (Ylr120C) and C. albicans (CaSap9; C3_03870cp_a) were aligned and colored by the Geneious Basic version 5.6.4 program. Identical and conserved residues are shaded in green and greenish-brown colors, respectively. The conserved catalytic motifs (DTGSS and D(S/T)GTT) are marked with a red box. B, serial dilution spotting analysis. Overnight YPD-grown cultures of the indicated strains were taken, and A600 was normalized to 1.0. 3 μl of 10-fold serially diluted cultures were spotted on YNB, YNB (pH 2.0), and the YPD medium lacking or containing metal ions. Calcium chloride (CaCl2) and zinc chloride (ZnCl2) were used at a final concentration of 100 and 10 mm, respectively. After growth at 30 °C for 1–3 days, plates were imaged. V, C. glabrata strains carrying empty vector.

Through site-directed mutagenesis, two identified aspartate residues were individually converted to alanine, and the ability of mutant enzymes to complement the ion and low-pH sensitivity of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant was tested. CgYps1 has previously been implicated in survival of acid stress and resistance to surplus metal ions under normal and pH 7.5 conditions (16, 18). As shown in Fig. 2B, growth defects of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant in the pH 2.0 medium and the medium containing calcium chloride or zinc chloride could not be restored upon expression of the CgYps1 enzyme carrying D91A and D378A substitutions, indicating that both aspartic acid residues are required for cellular functions of CgYps1. As both Asp-91 and Asp-378 residues appear to be functionally important, CgYps1 carrying alanine in place of the aspartate at position 91 (CgYps1D91A) was used for further studies.

Next, we checked whether lower β-glucan and mannan levels, higher chitin content, and reduced biofilm formation in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant could be restored by expression of the putative catalytically dead CgYps1, but we found no phenotypic complementation (Fig. 1, C–F). Together, these results suggest that the predicted catalytic aspartate residue at position 91 of the CgYps1 enzyme is required for maintenance of cell wall homeostasis, whereas aspartic acid residues, which contribute to the proteolytic activity of CgYps7, are yet to be identified.

Response of human THP-1 macrophages to infection with C. glabrata WT and Cgyps1–11Δ mutant

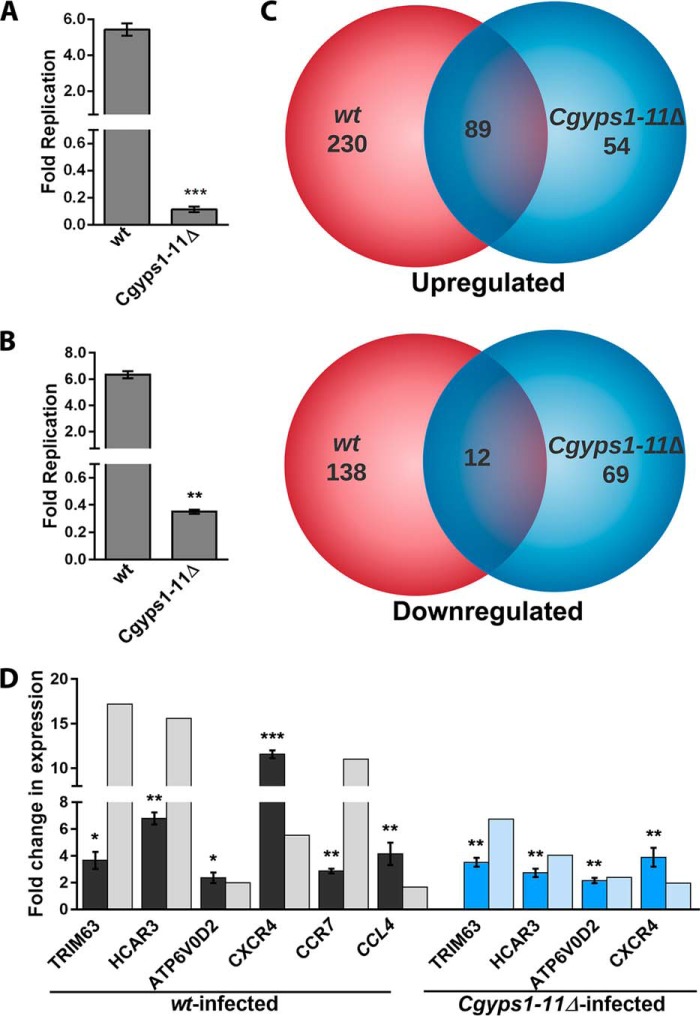

Cell wall polysaccharides have been implicated in activation of the host immune response both in vitro and in vivo (24–27). The above-described altered cell wall composition in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant led us to examine the transcriptional response of macrophages, which represent the first line of the defense machinery of the host innate immune system (28, 29), toward infection with mutant cells. For infection studies, THP-1 macrophages were generated by phorbol ester treatment of the human monocytic cell line THP-1. The Cgyps1–11Δ mutant has previously been reported to be killed in murine and human macrophages (9, 12). Consistently, after 24 h co-culturing, only 15% of Cgyps1-11Δ cells were found to be viable in THP-1 macrophages, whereas WT cells displayed about 5-fold replication (Fig. 3A). Similarly, WT cells displayed 6-fold replication, whereas the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant exhibited only 35% survival in human blood monocyte-derived macrophages (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that CgYps1–11 are required for intracellular survival of C. glabrata.

Figure 3.

C. glabrata infection to THP-1 cells invokes a transcriptional response. A and B, survival defect of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant in macrophages. C. glabrata WT and Cgyps1–11Δ mutant strains were infected to PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages (A) and macrophages derived from human peripheral blood monocytes (B) at 10:1 MOI, and intracellular yeast cfu were measured by plating macrophage lysates 2 and 24 h postinfection. Fold replication indicates the ratio of the number of intracellular C. glabrata cells at 24 h to that at 2 h postinfection. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of 3–4 independent experiments. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. C, Venn diagram illustrating overlap in differentially expressed genes between WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected THP-1 macrophages compared with uninfected cells. D, qPCR validation of microarray data. RNA was extracted using TRIzol from 6-h uninfected and WT- and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected THP-1 macrophages, and transcript levels of the indicated genes were measured by qPCR. Data (mean ± S.E., n = 3–4) were normalized against the GAPDH mRNA control and represent -fold change in expression in C. glabrata–infected macrophages compared with uninfected THP-1 macrophages. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; paired two-tailed Student's t test.

Next, to investigate whether gene expression is different between WT- and Cgyps1–11Δ-infected macrophages, we determined the transcriptional response, through genome-wide microarray analysis, of THP-1 macrophages to infection with WT and mutant cells for 6 h. The 6-h time point was chosen, as the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant is known to retain viability in THP-1 macrophages for 8 h (12). Transcript profiles were compared between WT- or Cgyps1–11Δ-infected and uninfected THP-1 cells. A total of 469 and 224 genes were found to be differentially regulated in WT-infected and Cgyps1–11Δ-infected THP-1 cells, respectively (Fig. 3C). Genes were considered to be differentially regulated if -fold change in expression compared with uninfected phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-treated THP-1 cells was >1.5-fold (p value <0.05). In WT-infected macrophages, 319 genes were up-regulated and 150 genes were down-regulated, whereas Cgyps1–11Δ-infected macrophages showed induction and repression of 143 and 81 genes, respectively (Fig. 3C and Tables S2 and S3). A set of 89 and 12 genes were common in up-regulated and down-regulated gene sets, respectively, between WT- and mutant-infected macrophages (Fig. 3C).

Transcriptional response of THP-1 cells to C. glabrata WT infection was largely represented by differential expression of genes involved in “chemotaxis,” “inflammatory response,” “regulation of GTPase activity,” “apoptosis,” and “signal transduction” (Table 1). An examination of the statistically significant enriched gene ontology terms for biological processes, using the DAVID functional annotation clustering tool, revealed many GO terms, including “negative regulation of cytokine secretion,” “negative regulation of inflammatory response,” “positive regulation of cytosolic calcium ion concentration,” and “ion transport” to be enriched in the up-regulated gene set. Further, GO process terms “tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-mediated signaling pathway,” “positive regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling,” and “positive regulation of MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) cascade” were found to be enriched in the down-regulated gene set of WT-infected macrophages (Table 1). These data suggest that THP-1 cells respond to C. glabrata infection by transcriptional induction of negative regulators of cytokine secretion and repression of MAPK, PI3K, and TNF signaling pathways.

Table 1.

GO-BP enrichment analysis of DEGs in C. glabrata WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected THP-1 macrophages

| GO ID | GO term | p |

|---|---|---|

| WT-infected THP-1 macrophages | ||

| Up-regulated DEGs | ||

| GO:0006935 | Chemotaxis | 0.0001 |

| GO:0007165 | Signal transduction | 0.0003 |

| GO:0006954 | Inflammatory response | 0.0003 |

| GO:0050710 | Negative regulation of cytokine secretion | 0.0008 |

| GO:0070098 | Chemokine-mediated signaling pathway | 0.0009 |

| GO:0050728 | Negative regulation of inflammatory response | 0.0015 |

| GO:0051209 | Release of sequestered calcium ion into cytosol | 0.0038 |

| GO:0001666 | Response to hypoxia | 0.0058 |

| GO:0006955 | Immune response | 0.0067 |

| GO:0007254 | JNK cascade | 0.0072 |

| GO:0051491 | Positive regulation of filopodium assembly | 0.0076 |

| GO:0043065 | Positive regulation of apoptotic process | 0.0079 |

| GO:0043401 | Steroid hormone mediated signaling pathway | 0.0121 |

| GO:0043547 | Positive regulation of GTPase activity | 0.0167 |

| GO:0060644 | Mammary gland epithelial cell differentiation | 0.0170 |

| GO:0060326 | Cell chemotaxis | 0.0189 |

| GO:0007204 | Positive regulation of cytosolic calcium ion concentration | 0.0190 |

| GO:0021794 | Thalamus development | 0.0196 |

| GO:0005975 | Carbohydrate metabolic process | 0.0199 |

| GO:0007049 | Cell cycle | 0.0213 |

| GO:0050729 | Positive regulation of inflammatory response | 0.0276 |

| GO:0006468 | Protein phosphorylation | 0.0280 |

| GO:0010039 | Response to iron ion | 0.0317 |

| GO:0001755 | Neural crest cell migration | 0.0333 |

| GO:0045766 | Positive regulation of angiogenesis | 0.0347 |

| GO:0007275 | Multicellular organism development | 0.0360 |

| GO:0006629 | Lipid metabolic process | 0.0373 |

| GO:0071345 | Cellular response to cytokine stimulus | 0.0460 |

| GO:2000345 | Regulation of hepatocyte proliferation | 0.0463 |

| GO:0006811 | Ion transport | 0.0496 |

| Downregulated DEGs | ||

| GO:0006954 | Inflammatory response | 0.0001 |

| GO:0043410 | Positive regulation of MAPK cascade | 0.0003 |

| GO:0060750 | Epithelial cell proliferation involved in mammary gland duct elongation | 0.0003 |

| GO:0014068 | Positive regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling | 0.0011 |

| GO:0070374 | Positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade | 0.0014 |

| GO:0097190 | Apoptotic signaling pathway | 0.0015 |

| GO:0010863 | Positive regulation of phospholipase C activity | 0.0017 |

| GO:0045778 | Positive regulation of ossification | 0.0030 |

| GO:0061036 | Positive regulation of cartilage development | 0.0054 |

| GO:0048663 | Neuron fate commitment | 0.0061 |

| GO:0060749 | Mammary gland alveolus development | 0.0061 |

| GO:0048146 | Positive regulation of fibroblast proliferation | 0.0063 |

| GO:0000187 | Activation of MAPK activity | 0.0067 |

| GO:0071346 | Cellular response to interferon-γ | 0.0073 |

| GO:1902895 | Positive regulation of pri-miRNA transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 0.0084 |

| GO:0032092 | Positive regulation of protein binding | 0.0088 |

| GO:0006898 | Receptor-mediated endocytosis | 0.0098 |

| GO:0006935 | Chemotaxis | 0.0105 |

| GO:0060326 | Cell chemotaxis | 0.0105 |

| GO:0001938 | Positive regulation of endothelial cell proliferation | 0.0124 |

| GO:0070098 | Chemokine-mediated signaling pathway | 0.0134 |

| GO:0072104 | Glomerular capillary formation | 0.0139 |

| GO:0055007 | Cardiac muscle cell differentiation | 0.0151 |

| GO:0008284 | Positive regulation of cell proliferation | 0.0163 |

| GO:0042981 | Regulation of apoptotic process | 0.0167 |

| GO:0014066 | Regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling | 0.0172 |

| GO:0043065 | Positive regulation of apoptotic process | 0.0186 |

| GO:0043552 | Positive regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity | 0.0196 |

| GO:0048701 | Embryonic cranial skeleton morphogenesis | 0.0196 |

| GO:0022414 | Reproductive process | 0.0208 |

| GO:0072138 | Mesenchymal cell proliferation involved in ureteric bud development | 0.0208 |

| GO:0003130 | BMP signaling pathway involved in heart induction | 0.0208 |

| GO:0030501 | Positive regulation of bone mineralization | 0.0247 |

| GO:0007188 | Adenylate cyclase-modulating G-protein–coupled receptor signaling pathway | 0.0274 |

| GO:0060686 | Negative regulation of prostatic bud formation | 0.0276 |

| GO:0045893 | Positive regulation of transcription, DNA-templated | 0.0276 |

| GO:0008584 | Male gonad development | 0.0279 |

| GO:0046854 | Phosphatidylinositol phosphorylation | 0.0279 |

| GO:0002062 | Chondrocyte differentiation | 0.0302 |

| GO:0007165 | Signal transduction | 0.0311 |

| GO:0002138 | Retinoic acid biosynthetic process | 0.0344 |

| GO:0061156 | Pulmonary artery morphogenesis | 0.0344 |

| GO:0043949 | Regulation of cAMP-mediated signaling | 0.0344 |

| GO:0060744 | Mammary gland branching involved in thelarche | 0.0344 |

| GO:0002548 | Monocyte chemotaxis | 0.0346 |

| GO:0001658 | Branching involved in ureteric bud morphogenesis | 0.0346 |

| GO:0000165 | MAPK cascade | 0.0365 |

| GO:0048015 | Phosphatidylinositol-mediated signaling | 0.0379 |

| GO:0045944 | Positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 0.0406 |

| GO:0045165 | Cell fate commitment | 0.0408 |

| GO:0003151 | Outflow tract morphogenesis | 0.0408 |

| GO:2001171 | Positive regulation of ATP biosynthetic process | 0.0411 |

| GO:0003150 | Muscular septum morphogenesis | 0.0411 |

| GO:0021978 | Telencephalon regionalization | 0.0411 |

| GO:0002320 | Lymphoid progenitor cell differentiation | 0.0411 |

| GO:0042487 | Regulation of odontogenesis of dentin-containing tooth | 0.0411 |

| GO:0071356 | Cellular response to tumor necrosis factor | 0.0416 |

| GO:0043547 | Positive regulation of GTPase activity | 0.0439 |

| GO:0007219 | Notch signaling pathway | 0.0464 |

| GO:0051782 | Negative regulation of cell division | 0.0478 |

| GO:0060449 | Bud elongation involved in lung branching | 0.0478 |

| GO:0045656 | Negative regulation of monocyte differentiation | 0.0478 |

| GO:0060687 | Regulation of branching involved in prostate gland morphogenesis | 0.0478 |

| GO:0033209 | Tumor necrosis factor–mediated signaling pathway | 0.0494 |

| Cgyps1–11Δ–infected THP-1 macrophages | ||

| Up-regulated DEGs | ||

| GO:0051607 | Defense response to virus | 0.0253 |

| GO:0009615 | Response to virus | 0.0381 |

| GO:0007420 | Brain development | 0.0395 |

| GO:0006139 | Nucleobase-containing compound metabolic process | 0.0430 |

| Down-regulated DEGs | ||

| GO:0060412 | Ventricular septum morphogenesis | 0.0051 |

| GO:0032729 | Positive regulation of interferon-γ production | 0.0125 |

| GO:0001570 | Vasculogenesis | 0.0182 |

| GO:0061156 | Pulmonary artery morphogenesis | 0.0183 |

| GO:0007179 | Transforming growth factor β receptor signaling pathway | 0.0454 |

| GO:0001916 | Positive regulation of T cell–mediated cytotoxicity | 0.0470 |

| GO:0051145 | Smooth muscle cell differentiation | 0.0470 |

| GO:0008584 | Male gonad development | 0.0472 |

In our microarray data sets, 5 and 10 genes belonging to the GO term “chemotaxis” were repressed and induced, respectively. This differentially regulated gene set was represented primarily by genes encoding CC and CXC chemokines and their receptors, which suggests that C. glabrata infection leads to a strong chemotactic cell migration response. Notably, C. glabrata cells have been postulated to induce increased migration of monocytes to the site of infection (30), and macrophages are considered as “Trojan horses” for C. glabrata (7, 30). Hence, it is possible that a strong chemotactic response generated by macrophages may dampen the recruitment of neutrophils, which possess the ability to kill C. glabrata cells (31).

A closer inspection of individual gene expressions revealed that genes implicated in the inflammatory response, CXCR4, TLR7, CCRL2, CEBPB, and P2RX7, were induced in THP-1 macrophages in response to infection with both WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cells, which is reflective of a common transcriptional response of THP-1 cells to C. glabrata infection. Of note, C. albicans infection is known to result in production of chemokines and their receptors in monocytes and THP-1 macrophages, including CCR7, CCL3 (MIP-1α), and CCL4 (MIP-1β) (32, 33), whereas the CCL4 (MIP-1β) has previously been shown to be induced upon interaction of C. glabrata with polymorphonuclear cells (30). Moreover, up-regulation of the anti-apoptotic BCL2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) gene in both WT- and mutant-infected macrophages is consistent with the earlier observation of lack of apoptosis in human monocyte-derived macrophages upon C. glabrata infection (10).

Next, we focused on differences in the gene expression pattern between WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ mutant–infected macrophages. Although they share a set of 89 common up-regulated genes, indicating that infection with both C. glabrata strains leads to a largely similar transcriptional induction response, the DAVID analysis for significant enriched GO terms suggested otherwise. Instead of GO terms “negative regulation of cytokine secretion” and “negative regulation of inflammatory response,” GO terms “defense response to virus,” “brain development,” and “nucleobase-containing compound metabolic process” were found to be enriched in Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages (Table 1).

Further, a detailed analysis of differential gene expression pattern between WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages revealed that of 15 “chemotaxis” genes (PTAF4, PLAU, FPR1, CXCL1, CXCL16, CCRL2, CCR10, CCL1, CCL2, CCL20, CCL28, CCR7, CXCR3, CXCR4, and CXCR7) differentially regulated in WT-infected macrophages, only two genes (CXCR4 and CCRL2) were up-regulated in mutant-infected macrophages. Similarly, of seven up-regulated genes (CXCR4, CCR7, GPER, ADM, SWAP70, CCR10, and CCL28) that belong to the “positive regulation of cytosolic calcium ion concentration” GO term, only one gene (CXCR4) was up-regulated in mutant-infected macrophages. Furthermore, whereas genes involved in positive regulation of MAPK cascade, positive regulation of PI3K signaling, and TNF-mediated signaling pathways were down-regulated in WT-infected macrophages, genes implicated in ventricular septum morphogenesis, transforming growth factor β receptor signaling pathway, positive regulation of interferon-γ production, and vasculogenesis processes were down-regulated in Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages (Table 1). Altogether, these data point toward a subdued and differential immune response invoked by the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant upon infection to THP-1 macrophages. It is also possible that the inability of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant to repress the transcriptional machinery of key signaling cascades results in its death in THP-1 macrophages.

Last, to validate the microarray expression data, we performed qPCR analysis for highly induced HCAR3, TRIM63, ATP6V0D2, CXCR4, CCR7, and CCL4 genes. HCAR3, TRIM63, ATP6V0D2, CXCR4, CCR7, and CCL4 genes code for the hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 3, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase–containing tripartite motif, H+-transporting ATPase V0 subunit d2, chemokine (CXC motif) receptor 4, chemokine (CC motif) receptor 7, and chemokine (CC motif) ligand 4, respectively. The first four genes were up-regulated in WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages, compared with uninfected macrophages, whereas the CCR7 and CCL4 genes were uniquely induced in WT-infected macrophages in the microarray experiment. In agreement, all six genes displayed the same expression pattern in the qPCR experiment (Fig. 3D).

Overall, our global gene expression analysis revealed that THP-1 cells respond to WT C. glabrata infection via differential expression of genes involved in inflammatory response, chemotaxis, regulation of GTPase activity, and chemokine-mediated signaling pathway (Table 1). On the contrary, mutant-infected macrophages primarily displayed up-regulation of viral response gene expression (Table 1). The observed differential gene expression between WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages, however, was not simply due to lower internalization rates, as both strains were ingested at equal efficiency and displayed similar intracellular counts at 2 h postinfection. Thus, in all likelihood, differential gene expression patterns of WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected THP-1 cells reflect the individual yeast strain's ability to elicit the macrophage immune response.

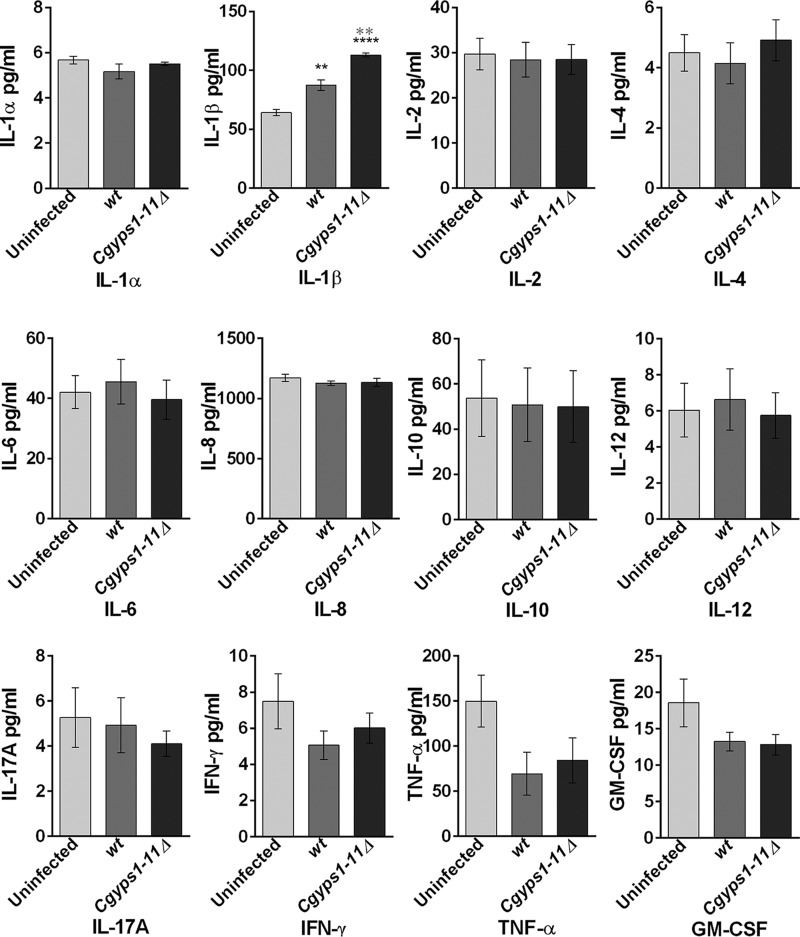

THP-1 macrophages produce IL-1β in response to C. glabrata infection

Next, we examined whether differences in gene expression pattern between WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages are mirrored in the release of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. To test this, we measured the levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17A, IFN-γ, TNFα, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in culture media of either uninfected THP-1 cells or THP-1 macrophages infected with WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cells for 24 h. Notably, infection of C. glabrata, unlike that of S. cerevisiae and C. albicans, is known to induce reduced production of IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, IL-1β, and IFN-γ in human monocyte-derived macrophages (10). However, GM-CSF production was robust upon C. glabrata infection (10).

As shown in Fig. 4, C. glabrata infection led to no significant production of any cytokine in THP-1 macrophages except for IL-1β. A 1.4-fold higher level of IL-1β was observed in WT-infected macrophages compared with uninfected macrophages (Fig. 4). Differential cytokine profiles of C. glabrata–infected THP-1 cells and monocyte-derived macrophages could be due to different type or nature (cultured versus primary) of the cells. Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages released 2-fold higher amounts of IL-1β in the culture media compared with uninfected macrophages, and the difference in IL-1β secretion between WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages was also statistically significant (Fig. 4). These results suggest that one function of CgYapsins is to keep IL-1β production and secretion in check in macrophages. As other proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-6, were not induced upon C. glabrata infection, we probed deeper to understand the basis for specific induction of IL-1β production.

Figure 4.

CgYapsins are required to suppress the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β. Shown is analysis of the indicated cytokines in uninfected and WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected THP-1 macrophages. PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells were either left uninfected or infected with C. glabrata WT and Cgyps1–11Δ mutant for 24 h. Expression of cytokines was evaluated in 100 μl of culture medium using the Multi-Analyte ELISArray kit. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of 3–4 independent experiments. Statistically significant differences in IL-1β levels between uninfected and C. glabrata–infected and between WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages are indicated by black and gray asterisks, respectively. **, p < 0.01, ****, p < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test.

IL-1β is a key mediator of the inflammatory response and is synthesized by activated macrophages as a pro-protein, which, upon proteolytic cleavage by the caspase 1 enzyme, is converted to its active form (34). C. albicans infection has previously been shown to result in pro-IL-1β production and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which depends upon the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) (35). Syk also plays an important role in activated immunoglobulin Fc receptor signaling (36).

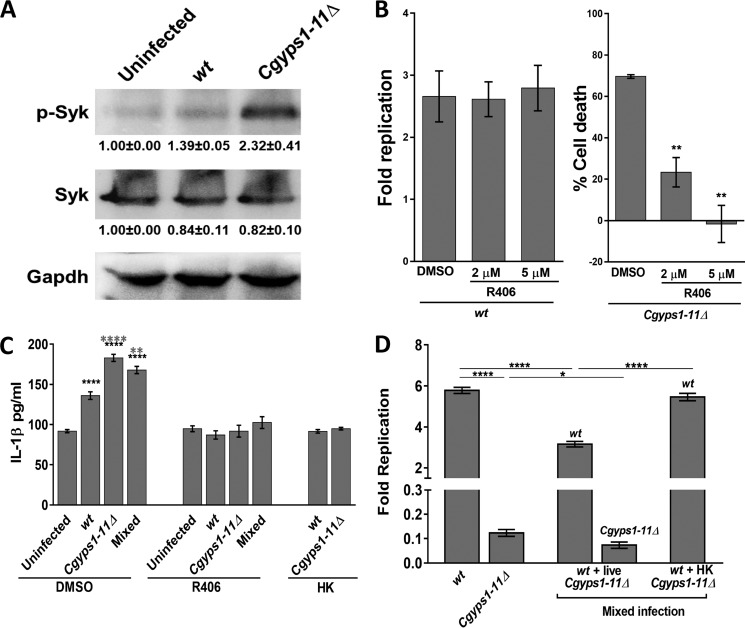

To determine the signaling pathway that contributes to elevated IL-1β production in Cgyps1–11Δ–infected THP-1 cells, we first checked whether Syk is activated in response to C. glabrata infection. We observed a 1.4- and 2.3-fold higher Syk phosphorylation in WT–infected and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages, respectively, compared with uninfected THP-1 cells (Fig. 5A), indicative of a hyperactivated Syk in Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages. We next verified these results using the kinase inhibitor approach. R406, a specific, ATP-competitive inhibitor of Syk, is known to impede Syk-dependent Fc receptor–mediated activation of macrophages and C. albicans-mediated activation of the inflammasome (35, 36). We reasoned that if macrophage-mediated killing of Cgyps1–11Δ cells is due to increased IL-1β levels and hyperactive Syk, their inhibition should rescue mutant cell death in THP-1 cells. Hence, we treated WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected THP-1 cells with R406 and determined intracellular growth profiles of yeast cells. We also checked whether R406 treatment had any effect on viability of THP-1 cells and found none. Whereas intracellular proliferation of C. glabrata WT cells remained unaffected by R406 treatment of THP-1 cells, viability loss of Cgyps1–11Δ cells was rescued in R406-treated macrophages in an R406 dose–dependent manner (Fig. 5B). Of note, Cgyps1–11Δ cells did not display any intracellular replication, as the number of intracellular mutant cfu was similar at 2 and 24 h after infection in R406 (5 μm)-treated cells. However, compared with 30% cells remaining viable in untreated THP-1 cells, 75–100% of Cgyps1–11Δ cells retained viability in R406-treated THP-1 macrophages after 24 h of co-incubation (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that Syk inhibition allows the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant to survive in THP-1 macrophages. These data also indicate that Syk signaling activation has no role in the control of intracellular proliferation in vitro, as C. glabrata WT cells exhibited similar increase in intracellular cfu in R406-treated and untreated THP-1 cells (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Cgyps1–11Δ–induced IL-1β production in THP-1 macrophages depends on Syk. A, representative immunoblot illustrating phosphorylated Syk in uninfected, and WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected THP-1 macrophages. THP-1 cell extracts containing 120 μg of protein were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-phospho-Syk, anti-Syk, and anti-GAPDH antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. For quantification, intensity of individual bands in three independent Western blots was measured using the ImageJ densitometry software. Total Syk and phosphorylated Syk signal in each lane was normalized to the corresponding GAPDH signal (considered as 1.0). Data (mean ± S.E. (error bars)) are presented as -fold change in signal intensity levels in infected samples compared with uninfected samples (taken as 1.0) below the blot. B, intracellular survival of WT and Cgyps1–11Δ mutant in R406-treated THP-1 macrophages. 2 and 5 μm R406 was added to THP-1 macrophages 2 h before C. glabrata infection, and infection was continued in the presence of R406. Fold Replication for WT cells indicates the ratio of the number of intracellular C. glabrata cells at 24 h to that at 2 h postinfection. Percentage cell death for the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant indicates viability loss of mutant cells in DMSO- and R406-treated THP-1 cells between 2 and 24 h of infection, as determined by measurement of intracellular cfu at these two time points. Data represent mean ± S.E. (n = 3). **, p < 0.01; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. C, measurement of secreted IL-1β in DMSO- or R406-treated, C. glabrata–infected THP-1 cells. THP-1 macrophage infection was done as described in the legend to Fig. 5B with C. glabrata cells at an MOI of 1:1, and IL-1β levels in the culture supernatant were measured after 24 h using the human IL-1β ELISA Set II kit. HK, heat-killed dead C. glabrata cells that were obtained after incubation at 95 °C for 20 min. Mixed infection, co-infection of THP-1 cells with WT- and Cgyps1–11Δ cells. Notably, R406 treatment abolished C. glabrata–induced IL-1β production in THP-1 cells. Data (mean ± S.E.; n = 4–8) represent secreted IL-1β levels under the indicated conditions. Statistically significant differences in IL-1β levels between uninfected and C. glabrata–infected and between WT- and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages are indicated by black and gray asterisks, respectively. **, p < 0.01, ****, p < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. D, assessment of intracellular proliferation of WT cells in THP-1 macrophages infected with live WT and live or dead Cgyps1–11Δ cells. The total number of C. glabrata cells infected to THP-1 macrophages was the same (1 × 105) in both single and mixed infections. Fold Replication indicates the ratio of the number of intracellular C. glabrata cells at 24 h to that at 2 h postinfection. Data represent mean ± S.E. of 4–6 independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; ****, p < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test.

Next, to check whether R406 treatment dampens IL-1β production, we measured cytokine levels in R406-treated THP-1 macrophages. As observed earlier (Fig. 4), C. glabrata infection led to higher IL-1β production (Fig. 5C). However, we found no increase in secreted IL-1β in R406-treated, WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages compared with R406-treated uninfected macrophages (Fig. 5C). Importantly, increase in IL-1β levels was also not observed when THP-1 macrophages were infected with heat-killed WT or Cgyps1–11Δ cells (Fig. 5C). Collectively, these results link rescue of the mutant viability loss with IL-1β levels in THP-1 cells and support the following four key conclusions. First, IL-1β production in THP-1 cells, upon C. glabrata infection, depends on Syk. Second, the Syk-dependent IL-1β production requires live C. glabrata cells. Third, CgYapsins are required to suppress this inflammatory response of THP-1 cells. Fourth, Cgyps1–11Δ cell death in THP-1 macrophages is, in part, due to activated Syk signaling and higher IL-1β production.

Further, we checked whether Cgyps1–11Δ-induced IL-1β production and macrophage activation had an effect on intracellular replication of WT C. glabrata cells. For this, we co-infected THP-1 cells with WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cells at the same time. In this mixed infection, WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cells were added in equal ratio (5 × 104 cells/strain), and intracellular cfu of both strains were found to be similar after 2-h internalization by THP-1 macrophages. As shown in Fig. 5D, WT cells proliferated 5.6-fold when infected singly to THP-1 macrophages. In contrast, they displayed 40% less intracellular replication when co-infected with Cgyps1–11Δ mutant cells (Fig. 5D). This adverse effect on replication of WT cells depended upon the presence of live Cgyps1–11Δ cells, as WT cells proliferated 5.5-fold during the mixed infection of dead Cgyps1–11Δ and WT cells to THP-1 macrophages (Fig. 5D). Of note, THP-1 cells co-infected with live WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cells secreted 23% more IL-1β compared with WT strain–infected macrophages (Fig. 5C). This increase depended on Syk activation, as R406-treated macrophages showed no increase in IL-1β levels upon co-infection with WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cells (Fig. 5C). Of note, the decreased intracellular replication of WT cells in mixed live strain macrophage infection is unlikely to be solely due to increased IL-1β production and secretion, as R406-dependent reduction in IL-1β levels earlier had no effect on WT proliferation (Fig. 5B). Importantly, the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant could not survive in THP-1 cells, regardless of whether the infection was mixed or single (Fig. 5D). However, the mutant did show 50% lower survival in mixed infections (Fig. 5D), whose molecular basis is yet to be determined.

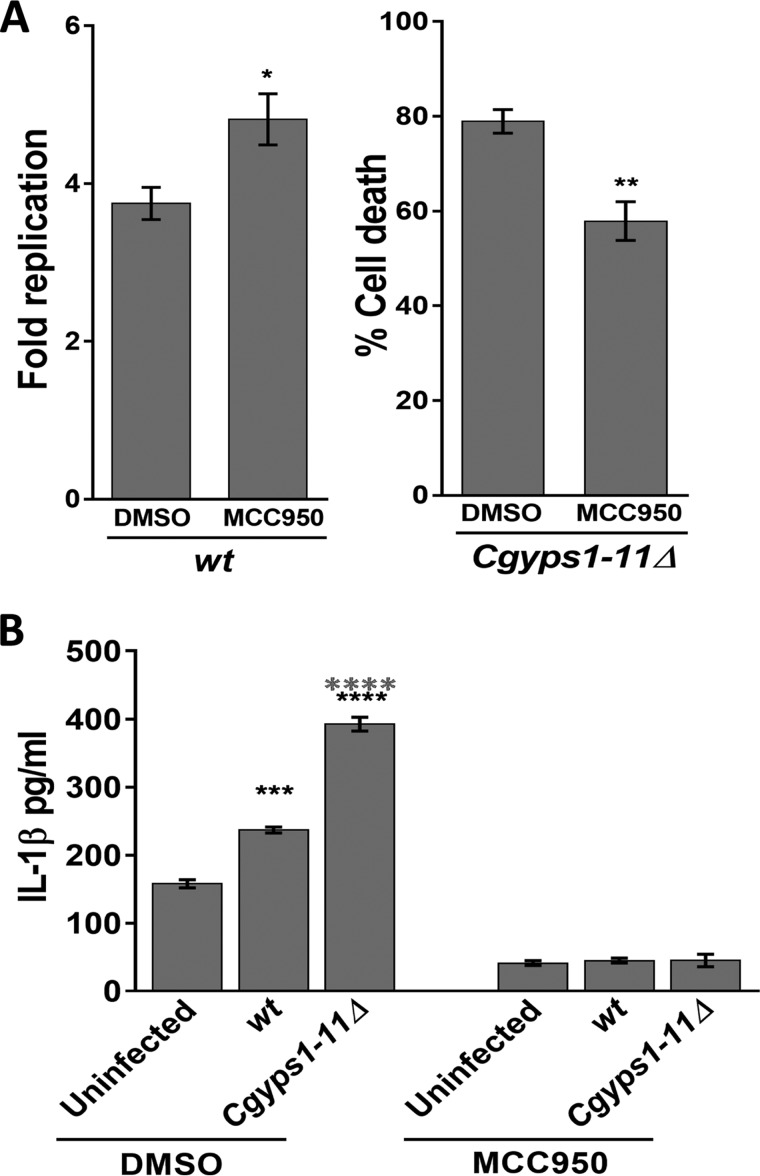

Last, we checked whether IL-1β production depends upon activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. For this, we used the inhibitor MCC950, which specifically blocks NLRP3 activation (37), and first monitored intracellular growth of C. glabrata in THP-1 macrophages treated with MCC950. Compared with DMSO-treated THP-1 cells, WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cells displayed 1.3-fold higher replication and 2.0-fold better survival, respectively, in MCC950-treated THP-1 macrophages (Fig. 6A). Next, we measured C. glabrata–invoked IL-1β production, and found that the MCC950 treatment completely abolished IL-1β production in THP-1 cells (Fig. 6B). These data implicate the NLRP3 inflammasome in IL-1β production and control of C. glabrata infection.

Figure 6.

NLRP3 inflammasome activation is required for C. glabrata-evoked IL-1β production in THP-1 macrophages. A, intracellular survival of WT and Cgyps1–11Δ mutant in MCC950-treated THP-1 macrophages. 15 μm MCC950 was added to THP-1 macrophages 2 h before C. glabrata infection, and infection was continued in the presence of MCC950. Fold Replication for WT cells indicates the ratio of the number of intracellular C. glabrata cells at 24 h to that at 2 h postinfection. Percentage cell death for the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant indicates viability loss of mutant cells in DMSO- and MCC950-treated THP-1 cells between 2 and 24 h of infection, as determined by measurement of intracellular cfu at these two time points. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. B, measurement of secreted IL-1β in DMSO- or MCC950 (15 μm)-treated, C. glabrata–infected THP-1 cells. THP-1 macrophage infection was done as described in the legend to Fig. 5B with C. glabrata cells at an MOI of 1:1, and IL-1β levels in the culture supernatant were measured after 24 h. Data (mean ± S.E.; n = 3–4) represent secreted IL-1β levels under the indicated conditions. Statistically significant differences in IL-1β levels between uninfected and C. glabrata–infected and WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages are indicated by black and gray asterisks, respectively. ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test.

Altogether, our results suggest that enhanced production and secretion of IL-1β is likely to be deleterious to the survival of C. glabrata in macrophages, and fungal cell surface–associated aspartyl proteases are pivotal to the regulation of synthesis and/or secretion of this pro-inflammatory cytokine.

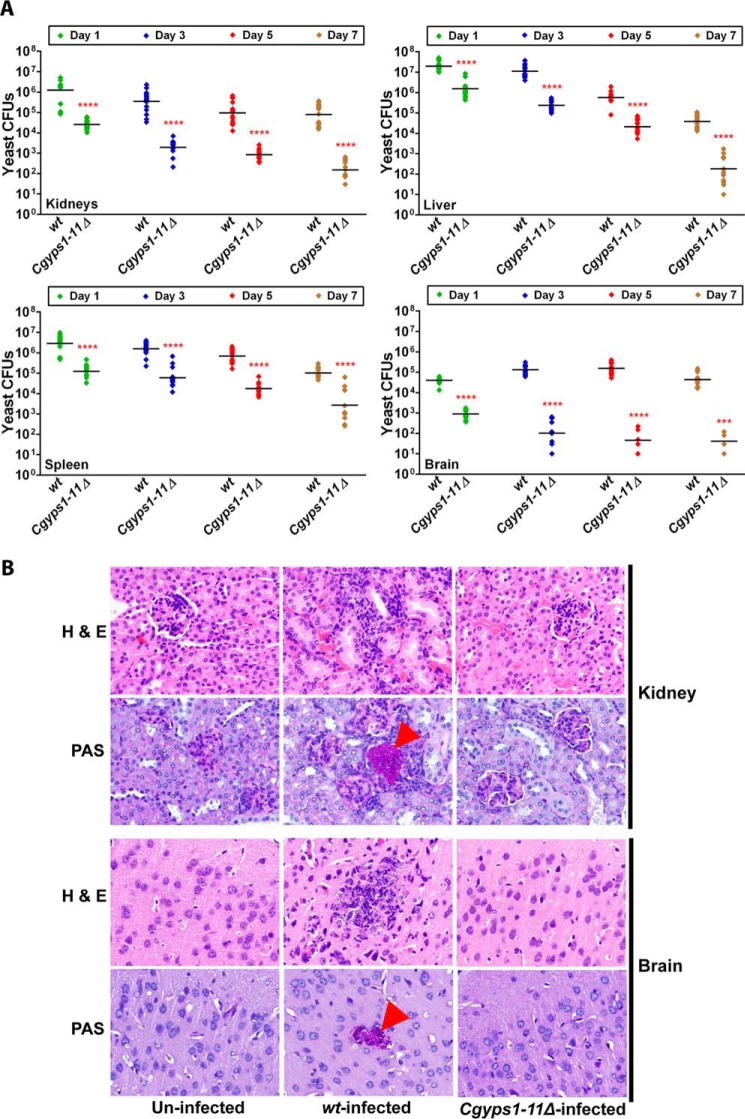

C. glabrata infection invokes IL-1β production in the mouse model of systemic candidiasis

The Cgyps1–11Δ mutant–induced enhanced production of IL-1β in THP-1 macrophages prompted us to examine its effects in vivo. The Cgyps1–11Δ mutant is reported to be highly attenuated for virulence, after 7 days of infection, in the murine model of disseminated candidiasis, wherein organ fungal burden was taken as the end point (9). As the role of CgYapsins in colonization and dissemination of C. glabrata cells is yet to be understood, we decided to study the kinetics of C. glabrata infection in the mouse model of systemic candidiasis before any cytokine detection analysis. To achieve our goal, we injected female BALB/c mice with 4 × 107 cells of either WT or the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant strain through the tail vein and assessed fungal burden in four organs, kidneys, liver, spleen, and brain, at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days postinfection (dpi). As shown in Fig. 7A, at day 1, mouse kidneys were colonized with 1.2 × 106 WT cells, whereas only 2.6 × 104 Cgyps1–11Δ cells represented renal fungal burden in the Cgyps1–11Δ–infected mice. Similarly, 13–45-fold lower cfu were recovered from other organs of the Cgyps1–11Δ–infected mice compared with the WT-infected mice 1 dpi (Fig. 7A), indicating that CgYapsins are required for the initial colonization and dissemination of C. glabrata cells. As the time course progressed, there was a constant decrease in the number of yeast cells that were harvested from kidneys, liver, and spleen of the WT-infected mice (Fig. 7A). These results preclude any significant multiplication of C. glabrata cells in these mouse organs.

Figure 7.

CgYapsins are required for colonization and dissemination to the brain in the mouse model of systemic candidiasis. A, kinetics of infection of C. glabrata WT and Cgyps1–11Δ cells in BALB/c mice. Mice were infected intravenously and sacrificed at the indicated days, and fungal burden in kidneys, liver, spleen, and brain was determined using a cfu-based assay. Diamonds, yeast cfu recovered from organs of the individual mouse; horizontal line, cfu geometric mean (n = 12–16) for each strain. Statistically significant differences in cfu between WT- and Cgyps1–11Δ-infected mice are marked (***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001; Mann–Whitney test). Of note, we could retrieve Cgyps1–11Δ cfu from the brain of only four mice of 14 infected animals 7 dpi. B, representative photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin– and PAS–stained kidney and brain sections from uninfected, WT-infected, and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected mice on day 3 after infection. Magnification was ×40. The arrowheads in tissue sections indicate PAS-positive yeast cells.

Strikingly, the fungal burden in brain at 3 dpi was 3-fold higher than that observed at 1 dpi (Fig. 7A), suggesting that C. glabrata WT cells either take longer to reach the brain or undergo multiplication in the brain. Brain cfu for the WT strain remained similar between 3 and 5 dpi, whereas a 2-fold decrease was observed 7 dpi (Fig. 7A). Histological analysis of periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-stained kidney and brain sections of WT-infected mice 3 dpi revealed the presence of C. glabrata cells in the form of a microcolony (Fig. 7B). However, no appreciable histological changes were observed in hematoxylin and eosin–stained tissue sections from WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected mice compared with uninfected control mice (Fig. 7B). Consistent with an earlier report (11), these data suggest that C. glabrata infection does not lead to any gross abnormality in the tissue architecture.

Notably, Cgyps1–11Δ cells failed to colonize and/or migrate to the brain in substantial numbers, with a drastic decline in the mutant number at later time points (Fig. 7A). In fact, of 14 Cgyps1–11Δ–infected mice, mutant cells were recovered from the brain of only four mice 7 dpi (Fig. 7A). The Cgyps1–11Δ mutant did not fare well in other organs either, with mouse organ fungal burden decreasing sharply (Fig. 7A). These findings were corroborated with histological analysis, wherein no yeast colonies were observed in kidney and brain sections of the Cgyps1–11Δ–infected mice 3 dpi (Fig. 7B). Notably, PAS-stained kidney and brain sections of WT-infected mice did reveal the presence of yeast colonies (Fig. 7B). Together, these data suggest that CgYapsins are required for colonization, dissemination, and persistence on prolonged infection of C. glabrata in the brain, kidneys, liver, and spleen as well as for plausible replication in the brain during early stages of infection. These results are consistent with an earlier study reporting the CgYapsin requirement for survival in kidneys, liver, and spleen 7 dpi during systemic infections of mice (9).

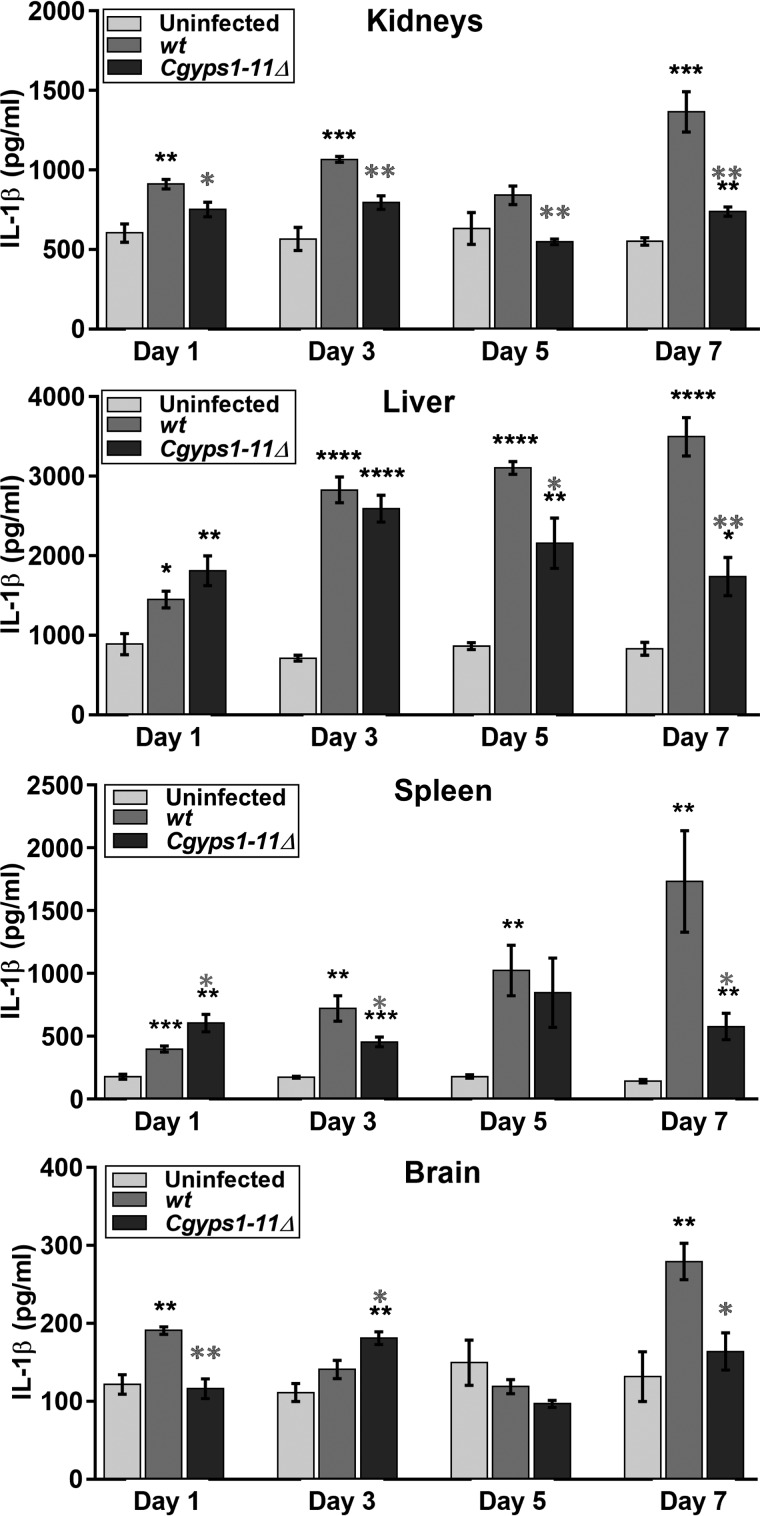

Next, to examine whether rapid clearance of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant from mouse organs is due to induction of the inflammatory response, we measured levels of the cytokine IL-1β in tissue homogenates at 1, 3, 5, and 7 dpi. Enhanced IL-1β production was observed in all organs in WT-infected mice, whereas IL-1β levels were higher only in liver and spleen of the Cgyps1–11Δ–infected mice at 1 dpi (Fig. 8). Further, although IL-1β levels varied at later time points, significantly higher (2–12-fold) IL-1β amounts were still observed 7 dpi in kidneys, liver, spleen, and brain of WT–infected mice compared with uninfected mice (Fig. 8). Notably, IL-1β levels were lower overall in all organs of the Cgyps1–11Δ–infected mice compared with WT-infected mice at 7 dpi (Fig. 8), which appears to correlate partially with the mutant cfu burden in organs. These findings suggest that regulated production and release of IL-1β occurs probably to control C. glabrata infection in vivo; however, inability of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant to survive in mice is not due to increased production of IL-1β in tissues.

Figure 8.

C. glabrata infection invokes IL-1 β production in the mouse model of systemic candidiasis. Measurement of secreted IL-1β in tissue homogenates of kidneys, liver, spleen, and brain of mice infected with WT or Cgyps1–11Δ cells at the indicated days using the mouse IL-1β/IL-1F2 DuoSet ELISA kit. Data (mean ± S.E. (error bars), n = 4) represent IL-1 β levels under the indicated conditions. Statistically significant differences in IL-1β levels between uninfected and C. glabrata–infected, and WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected mice are indicated by black and gray asterisks, respectively. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test.

Overexpression of CgYps4, -5, -8, and -10 partially rescues intracellular survival defect of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant

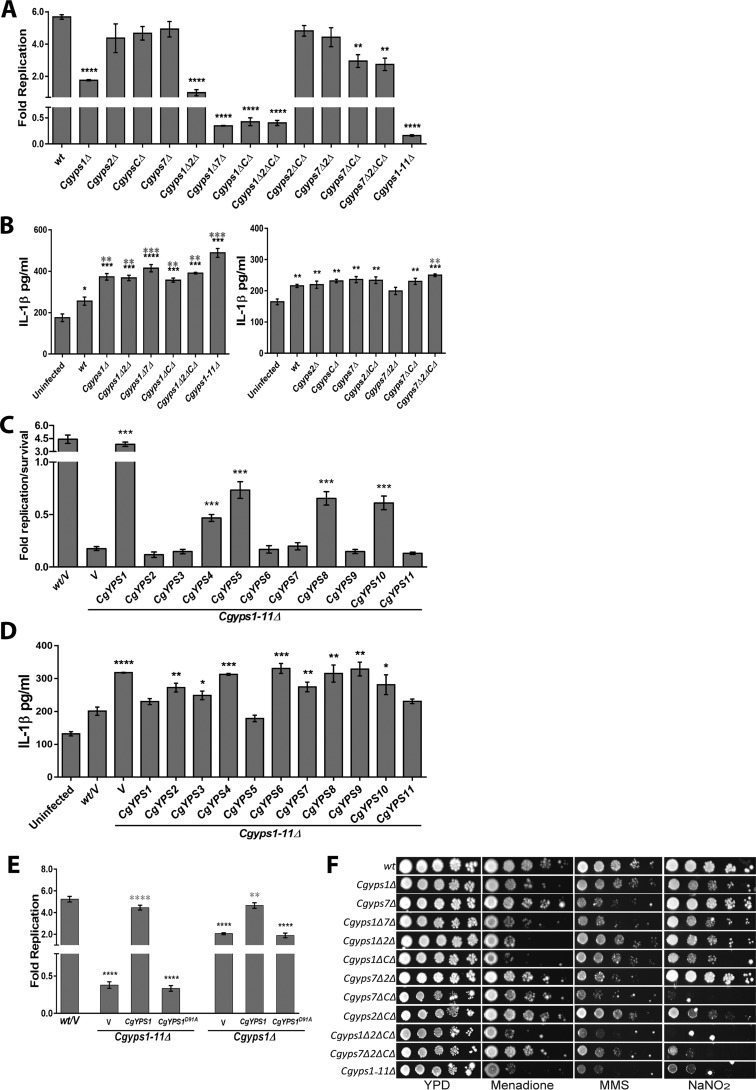

All intracellular survival and replication studies, so far, were carried out with the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant, which lacks all 11 CgYapsins. Therefore, next, to investigate which of these yapsin proteins is crucial to survival of C. glabrata cells in the host, we conducted macrophage and BALB/c mouse infection studies with mutants deleted for single, double, and multiple CgYps-encoding genes. Analysis of intracellular replication of different strains revealed that in addition to the 6.2-fold decline in viability of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant, Cgyps1Δ7Δ, Cgyps1ΔCΔ, and Cgyps1Δ2ΔCΔ mutants exhibited 2.5–3.0-fold lower survival in THP-1 macrophages compared with 100% viability of the respective mutant strain at 2 h (Fig. 9A). These data indicate that lack of CgYps1 in conjunction with CgYps7, CgYpsC, and CgYps2&C affected intracellular survival of C. glabrata. In contrast, deletion of CgYPS7 either alone or in conjunction with CgYPS2 had no effect on intracellular proliferation (Fig. 9A). However, Cgyps7ΔCΔ and Cgyps7Δ2ΔCΔ mutants replicated 2-fold slower in THP-1 macrophages, compared with WT cells (Fig. 9A). Similarly, disruption of CgYPS2 in the Cgyps1Δ background led to 1.8-fold less replication compared with Cgyps1Δ cells (Fig. 9A). Interestingly, Cgyps2Δ, CgypsCΔ, and Cgyps2ΔCΔ mutants displayed WT-like intracellular proliferation (Fig. 9A). Further, compared with WT-infected macrophages, enhanced IL-1β production was seen in THP-1 macrophages infected with Cgyps1Δ, Cgyps1Δ2Δ, Cgyps1Δ7Δ, Cgyps1ΔCΔ, Cgyps1Δ2ΔCΔ, Cgyps7Δ2ΔCΔ, and Cgyps1–11Δ mutants (Fig. 9B), which is in partial correlation with the intracellular survival pattern of CgypsΔ mutants. Overall, these data indicate a role for CgYPS-C (CgYPS3–6 and CgYPS8–11) genes in intracellular survival and/or replication of C. glabrata, as disruption of CgYPC-C genes adversely affected the survival and replication of Cgyps1Δ and Cgyps7Δ mutant, respectively. These results, consistent with findings of our earlier study in J774A.1 murine macrophages (9), suggest that C. glabrata cells do not replicate efficiently in the absence of CgYps1.

Figure 9.

CgYPS-C genes are required for survival of the macrophage internal milieu and nitrosative stress. A, intracellular growth profiles of the indicated CgypsΔ mutants in THP-1 macrophages. THP-1 macrophage infection was done as described in the legend to Fig. 3A with C. glabrata cells at an MOI of 10:1. Fold Replication indicates the ratio of the number of intracellular C. glabrata cells at 24 h to that at 2 h postinfection. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of 3–5 independent experiments. **, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. B, IL-1β was measured in the culture supernatant of uninfected THP-1 and THP-1 cells infected with the indicated C. glabrata strains as described in the legend to Fig. 6B. Data (mean ± S.E.; n = 3–5) represent secreted IL-1β levels under the indicated conditions. Statistically significant differences in IL-1β levels between uninfected and C. glabrata–infected and between WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages are indicated by black and gray asterisks, respectively. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. C, intracellular growth profiles of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant overexpressing individual CgYPS1–11 genes in THP-1 macrophages. Fold Replication indicates the ratio of the number of intracellular C. glabrata cells at 24 h to that at 2 h postinfection. Data represent mean ± S.E. of 3–5 independent experiments. V, C. glabrata strains carrying empty vector. ***, p < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. D, IL-1β was measured in the culture supernatant of uninfected THP-1 and THP-1 cells infected with the indicated C. glabrata strains as described in the legend to Fig. 6B. Data (mean ± S.E.; n = 4) represent secreted IL-1β levels under the indicated conditions. V, C. glabrata strains carrying empty vector. Statistically significant differences in IL-1β levels between WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ strain–infected macrophages are marked. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. E, intracellular survival of Cgyps1Δ and Cgyps1–11Δ mutant expressing either CgYps1 or putative catalytically dead CgYps1D91A in THP-1 macrophages. Fold Replication indicates the ratio of the number of intracellular C. glabrata cells at 24 h to that at 2 h postinfection. Data represent mean ± S.E. of 3–7 independent experiments. Black asterisks, statistically significant differences between WT and mutants carrying either vector or CgYps1D91A protein. Gray asterisks, statistically significant differences between mutants carrying vector and CgYps1 protein. **, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. F, serial dilution spotting analysis of CgypsΔ mutants under the indicated conditions. Menadione, MMS, and sodium nitrite (NaNO2) were used at a final concentration of 50 mm, 0.04%, and 60 mm, respectively. Growth was recorded after 2 days of incubation at 30 °C.

To further corroborate our results, we cloned and ectopically expressed all 11 CgYPS genes from an intermediate-strength promoter, CgHHT2, in the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant and examined intracellular survival. We found that ectopic expression of CgYPS1 led to 4.5-fold replication of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant, whereas ectopic expression of CgYPS4, -5, -8, and -10 genes could partially rescue the viability loss of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant in THP-1 macrophages (Fig. 9C). Importantly, CgYPS7 overexpression had no positive effect on survival of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant (Fig. 9C), thereby precluding any role for CgYps7 in intracellular survival of C. glabrata in vitro. Interestingly, overexpression of CgYPS1, CgYPS5, and CgYPS11 in Cgyps1–11Δ cells evoked WT-like IL-1β production in THP-1 macrophages upon infection (Fig. 9D). As the CgYPS11-overexpressing Cgyps1–11Δ strain could not survive in THP-1 cells (Fig. 9C), the effect of CgYPS11 on IL-1β expression in THP-1 cells needs to be further examined.

Overall, gene overexpression results correlate well with mutant infection studies, wherein disruption of eight YPS-C (CgYPS3–6 and CgYPS8–11) genes adversely affected intracellular proliferation and survival of Cgyps7Δ and Cgyps1Δ mutant, respectively (Fig. 9A). These results also assign a function to CgYPS4, -5, -8, and -10 genes individually, for the first time, in the pathobiology of C. glabrata.

As described above, of 11 CgYapsins, CgYps1 appears to be the key modulator of intracellular replication of C. glabrata cells (Fig. 9A). Hence, we next checked whether the predicted catalytic aspartate residue at position 91 of CgYps1 is required for survival in macrophages. For this, we measured intracellular survival and replication of Cgyps1Δ and Cgyps1–11Δ mutants expressing either CgYPS1 or CgYPS1D91A allele. Expectedly, we found good complementation of mutant defects with CgYps1 expression (Fig. 9E). However, the putative catalytically dead CgYps1 could neither rescue the survival nor the proliferation defect of Cgyps1–11Δ and Cgyps1Δ mutant, respectively (Fig. 9E), suggesting that the predicted catalytic aspartate residue at position 91 of CgYps1 is necessary for intracellular survival and replication of C. glabrata in THP-1 macrophages.

Last, we examined whether intracellular behavior of CgypsΔ mutants could be mimicked in vitro in the presence of a stressor likely to be encountered in the macrophage internal milieu. Macrophages are known to generate reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in response to microbial pathogens that may cause DNA damage (38). Hence, we checked growth of different CgypsΔ mutants in the presence of the DNA-damaging agent methyl methane sulfonate (MMS) and nitrosative and oxidative stress–causing agents, sodium nitrite and menadione, respectively. We found mutants lacking CgYPS1 and CgYPS7 to be sensitive to menadione and MMS, respectively (Fig. 9F). Intriguingly, disruption of CgYPS-C genes in Cgyps1Δ, Cgyps7Δ, Cgyps1Δ2Δ, and Cgyps7Δ2Δ mutants led to significantly attenuated growth in the medium-containing sodium nitrite (Fig. 9F), suggesting that CgYPS-C genes contribute to survival under nitrosative stress conditions. In this context, it is noteworthy that six of eight CgYPS-C genes (CgYPS4–5 and CgYPS8–11) were up-regulated upon internalization by murine J774A.1 macrophages, and disruption of CgYPS-C and CgYPS2 genes in the Cgyps1Δ7Δ mutant significantly increased the nitric oxide production in J774A.1 cells compared with the Cgyps1Δ7Δ double mutant (9).

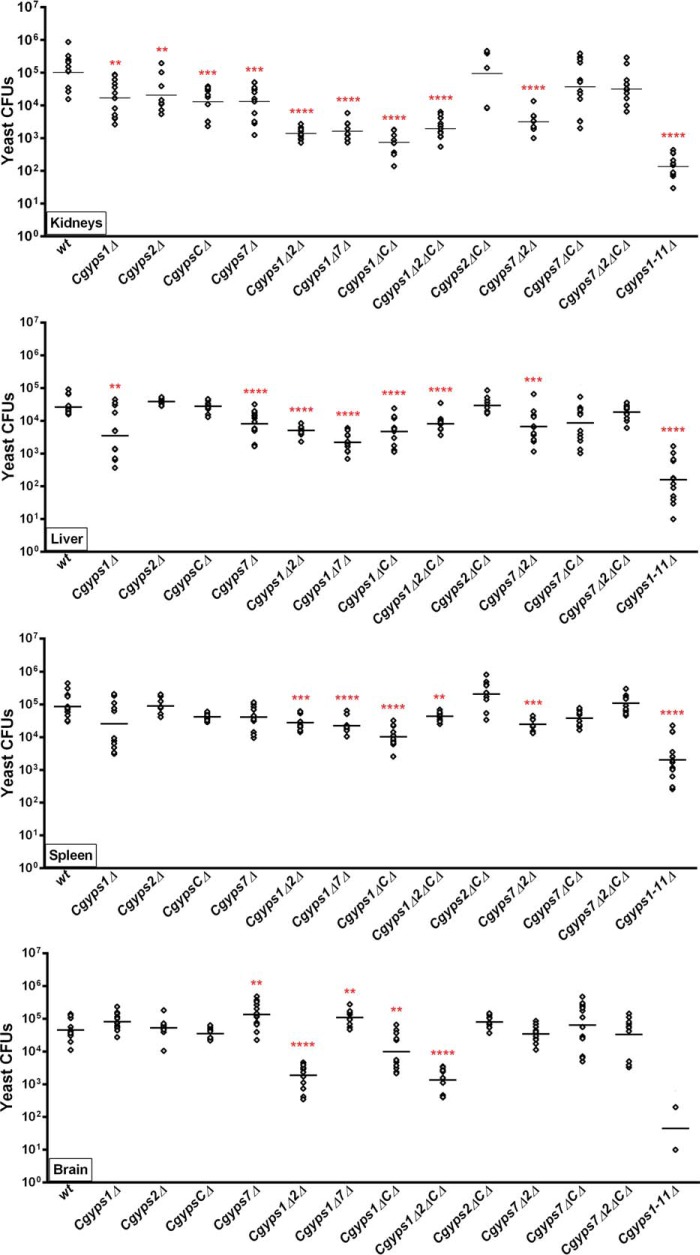

CgYPS2 and CgYPS-C genes are required for survival in the murine model of systemic candidiasis

Last, to delineate the role of CgYPS-C genes more precisely in virulence, we performed systemic infection studies in BALB/c mice with a panel of single, double, and multiple CgypsΔ mutants (Cgyps1Δ, Cgyps2Δ, CgypsCΔ, Cgyps7Δ, Cgyps1Δ2Δ, Cgyps1Δ7Δ, Cgyps1ΔCΔ, Cgyps1Δ2ΔCΔ, Cgyps2ΔCΔ, Cgyps7Δ2Δ, Cgyps7ΔCΔ, Cgyps7Δ2ΔCΔ, and Cgyps1–11Δ). We found mice infected with all mutant strains, but for mice infected with Cgyps2ΔCΔ, Cgyps7ΔCΔ, Cgyps7Δ2ΔCΔ mutants exhibited less renal fungal burden compared with the WT-infected mice at 7 dpi (Fig. 10). In contrast, fewer cfu were retrieved from spleen of the mice infected with Cgyps1Δ2Δ, Cgyps1Δ7Δ, Cgyps1ΔCΔ, Cgyps1Δ2ΔCΔ, Cgyps7Δ2Δ, and Cgyps1–11Δ mutants only (Fig. 10). Mice infected with all other mutants, including single Cgyps1Δ, Cgyps2Δ, and Cgyps7Δ mutants, displayed WT-like cfu in spleen (Fig. 10). These data indicate an organ-specific role of CgYapsins in survival in mice and were further strengthened by the fungal burden data of liver and brain. Whereas mice infected with all CgypsΔ mutants, except for Cgyps2Δ, CgypsCΔ, Cgyps2ΔCΔ, Cgyps7Δ2Δ, and Cgyps7Δ2ΔCΔ mutants, had less fungal burden in the liver (Fig. 10), only mice infected with Cgyps1Δ2Δ, Cgyps1ΔCΔ, Cgyps1Δ2ΔCΔ, and Cgyps1–11Δ strains showed less yeast cfu in the brain. Intriguingly, mice infected with mutants lacking CgYPS7 either singly or in combination with CgYPS1 showed higher fungal burden in the brain (Fig. 10). This was an unexpected result and could either imply a direct negative effect of CgYps7 on brain colonization and/or persistence or overexpression of factors in the Cgyps7-null mutant background that promote survival in the brain. Further investigations are currently under way to examine these two hypotheses.

Figure 10.

CgYps2 and CgYps-C proteins are required for survival in the murine systemic candidiasis model. BALB/c mice were infected intravenously with WT and the indicated CgypsΔ mutants. At 7 dpi, mice were sacrificed, and organ fungal burden was calculated via a cfu assay. Diamonds, yeast cfu recovered from organs of the individual mouse; horizontal line, cfu geometric mean (n = 8–14) for each strain. Statistically significant differences between cfu recovered from WT– and CgypsΔ–infected mice are marked (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001; Mann–Whitney test).

Overall, the organ fungal burden data are consistent with the previous report indicating a major role for CgYps1 and CgYps7 in survival in mice and demonstrating that the Cgyps2ΔCΔ mutant is not attenuated for virulence (9). However, our data also unravel four new findings. First, lack of CgYps7 facilitates survival in brain. Second, CgYps2 and CgYps-C are required for survival in kidney. Third, absence of either CgYPS2 or CgYPS-C genes has a strong negative effect on survival of the Cgyps1Δ mutant in kidney, liver, and spleen, which is similar in magnitude to that of the CgYPS7 deletion. Last, loss of CgYps-C reverses the survival defects of Cgyps7Δ and Cgyps7Δ2Δ mutants in kidney and liver, and kidney, liver, and spleen, respectively. Altogether, our data yield new insights into the role of CgYps2, CgYps7, and CgYps-C in organ-specific survival of C. glabrata during systemic infections.

Discussion

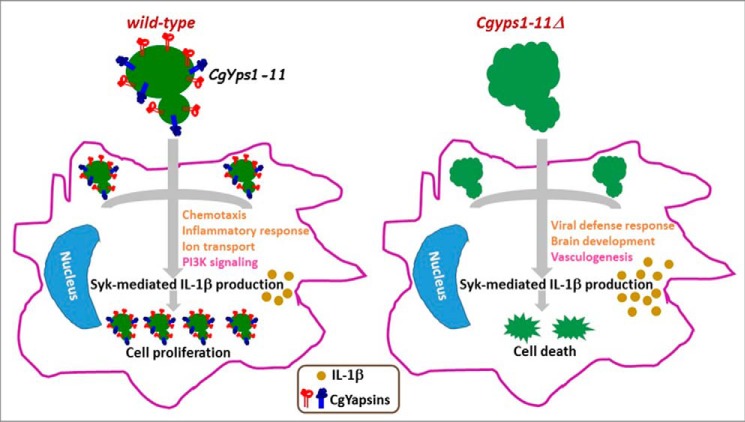

CgYapsins are pivotal to pathogenesis of C. glabrata (9). The Cgyps1–11Δ mutant, which lacks all 11 GPI-linked aspartyl proteases, is killed in macrophages and severely attenuated for virulence in the mouse systemic candidiasis model (9). Here, we examined how CgYapsins contribute to virulence and identify one mechanism by which they modulate the macrophage antifungal response. We demonstrated the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant to have altered cell wall polysaccharide attributes, which probably led, in part, to elicitation of an altered transcriptional response from THP-1 macrophages. Furthermore, Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages produced relatively high levels of IL-1β in a Syk-signaling dependent manner, which contributed to intracellular killing of the mutant. These data reveal two key findings. First, macrophages respond to C. glabrata infection through Syk activation and Syk-mediated release of IL-1β (Fig. 11). Second, CgYapsins impede the Syk-dependent IL-1β production/secretion (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Role of CgYapsins in interaction with macrophages. Shown is a schematic model illustrating the role of CgYapsins in regulating the interaction of C. glabrata with THP-1 macrophages. CgYapsins modulate the macrophage transcriptional response probably to facilitate intracellular survival of C. glabrata through regulated production of Syk-dependent IL-1β. Lack of CgYapsins leads to increased IL-1β levels, which results in cell death. Altered cell wall attributes of the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant are depicted through surface ridges. Transcriptionally up-regulated and down-regulated processes in infected THP-1 cells are indicated in light brown and pink, respectively.

The IL-1β signaling pathway is a key component of the innate immune system that regulates the expression of hundreds of genes in a context-dependent fashion (39, 40). The NLRP3 inflammasome, which plays a crucial role in host defense against C. albicans through regulation of IL-1β production, is an oligomeric complex comprising NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat containing receptor family member, pyrin domain–containing 3), adaptor protein ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing CARD (caspase activation and recruitment domain), and procaspase-1 (35, 41, 42). The procaspase-1 is cleaved into an active inflammatory cysteine protease caspase-1 following assembly of the inflammasome complex (40). IL-1β secretion, upon C. albicans–mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, involves transcriptional induction followed by caspase-1–mediated cleavage of the pro-IL-1β cytokine (42, 43). Notably, in addition to caspase-1, other proteases, including caspase-8, neutrophil-derived serine proteases, and C. albicans aspartyl proteases, have also been shown to process pro-IL-1β into active IL-1β (43). Recently, C. albicans secreted aspartyl proteases Sap2 and Sap6 caused IL-1β production through NLRP3 and caspase-1 activation in monocytes (44). In our study, we did not find higher transcript levels of IL-1β in microarray- and qPCR-based gene expression analysis of WT– and Cgyps1–11Δ–infected macrophages. Hence, it is possible that either higher IL-1β secretion, upon C. glabrata infection, is a post-transcriptional effect, or IL-1β transcriptional induction occurs very early during infection of THP-1 cells. Further, whether CgYapsins can cleave pro-IL-1β to produce mature IL-1β remains to be determined.

The C-type lectin receptors Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 on macrophages are known to act as pattern-recognition receptors for C. albicans through sensing of β-glucan and α-mannan, respectively, in the fungal cell wall (24, 45). β-Glucans have been reported to induce the transcription and secretion of IL-1β via Dectin-1/Syk signaling–dependent activation of the NRLP3 inflammasome in human macrophages (41, 46). Importantly, both Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 have recently been implicated in host resistance against systemic C. glabrata infections, as Dectin-1– and 2–deficient mice exhibited elevated susceptibility to C. glabrata infections (47, 48). The key finding of involvement of Syk-dependent IL-1β production in intracellular survival in our study is likely to be dependent on extracellular/intracellular sensing of C. glabrata components. In this regard, it is noteworthy that C. glabrata cell walls contain 50% higher mannoproteins than that of S. cerevisiae and C. albicans, although β-glucan content in the C. glabrata cell wall is lower (23). It has also been postulated that reduced β-glucan content may help C. glabrata evade detection by host innate immune cells (7, 23). Although the involvement of Syk signaling and NLRP3 inflammasome activation implicates β-glucan in recognition of Cgyps1–11Δ cells, additional work is required to delineate the IL-1β signaling and other macrophage signaling pathways that are involved in recognition and transduction of signal evoked by C. glabrata cells lacking or expressing CgYapsins. Notably, infection of Raw264.7 macrophages with live C. glabrata cells has previously been shown to result in prolonged activation of the Syk pathway while having no effect on the NF-κB pathway (49).

Further, using the mouse model of systemic candidiasis, we demonstrate for the first time that CgYapsins are required for colonization, dissemination, and persistence of C. glabrata in the brain. C. glabrata cells have previously been harvested from brains of systemically infected mice with no change in organ burden between 2 and 7 days postinfection (11). However, the process of fungal cells trafficking to and migrating into the brain is poorly understood. Cryptococcus neoformans is reported to invade brain through the “Trojan horse” mechanism and start crossing the blood–brain barrier 6 h after tail vein injection (50). It has also been shown to multiply in the brain (50). Our infection kinetics data show that compared with 106–107 cfu in kidneys, liver, and spleen 1 dpi, mouse brains displayed only 104 C. glabrata cfu. Furthermore, contrary to the decline in fungal burden in other organs, brain yeast cfu exhibited an increase at days 3 and 5 postinfection compared with 1 dpi. These results are consistent with findings of a previous study, wherein a small increase in brain cfu was observed from day 1 to day 3 during systemic C. glabrata infection of the immunocompetent mice (51). Altogether, these data do raise a possibility of modest multiplication of C. glabrata exclusively in the brain. Intriguingly, fungal migration/colonization and replication in the brain during early stages of systemic infection appear to be dependent on the presence of 11 CgYapsins, as the Cgyps1–11Δ mutant failed to reach, multiply, and persist in the brain in substantial numbers. Of note, CgYapsins have previously been implicated in colonization of D. melanogaster (17). How CgYapsins contribute to crossing the blood–brain barrier and modulate the immune cell response will be the focus of future investigation.

Last, we also uncover for the first time a role for CgYps2 in vivo and CgYps4, -5, -8, and -10 in intracellular survival in vitro, as the mutant lacking CgYPS2 and CgYPS-C genes has previously shown no discernible phenotype (9). Although functional redundancy, due to probable evolution by the ancestral gene duplication, is not surprising in the CgYPS gene family, it certainly has made it difficult to ascertain the role of individual CgYapsin proteins in cell physiology. We have tried to address this by conducting studies in parallel with strains overexpressing either an individual CgYPS gene or lacking single, double, and multiple CgYPS genes. Our data reveal for the first time that CgYps2 and CgYps-C are just as important for survival in kidneys as CgYps1 and CgYps7. Additionally, the Cgyps1Δ2Δ mutant, which largely phenocopies the Cgyps1Δ7Δ and Cgyps1ΔCΔ mutants, has a phenotype more severe than that observed in the single Cgyps1Δ mutant. These data indicate that CgYps2 has a function of its own rather than being completely redundant, as has previously been assumed (9, 16). The unexpected lack of any intracellular survival or virulence defect of the Cgyps2ΔCΔ mutant is currently being examined; it could be due to overexpression or stabilization of CgYps1 and/or CgYps7 proteins.

Overall, our data demonstrate that lack of CgYapsins augments the inflammatory response of macrophages during infection in an IL-1β–dependent manner, thereby underscoring the regulatory role of CgYapsins in the host innate immune response (Fig. 11). Our findings also imply that regulated IL-1β cytokine production, during colonization and dissemination of C. glabrata, may promote recruitment of phagocytic cells that allow yeast cells to persist in the immunocompetent mice.

Experimental procedures

Strains, media, and growth conditions

C. glabrata WT and mutant strains, derivatives of the BG2 strain, were routinely grown in the rich YPD medium at 30 °C. Yeast strains carrying plasmids were cultured either in the CAA or synthetically defined YNB medium. Bacterial strains and strains carrying plasmids were grown in the LB and LB medium containing ampicillin, respectively, at 37 °C. pH of the YNB and YPD medium was adjusted with the HEPES buffer and HCl/NaOH. Logarithmic-phase cells were obtained by incubating overnight-grown cultures in fresh medium for 4 h. Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Strains used in the study

| Yeast strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| YRK92 | URA3 Cgyps2Δ::hph | Ref. 9 |

| YRK94 | URA3 CgypsCΔ::hph | Ref. 9 |

| YRK96 | URA3 Cgyps1Δ2ΔCΔ::hph | Ref. 9 |

| YRK97 | URA3 Cgyps7Δ2ΔCΔ::hph | Ref. 9 |

| YRK103 | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418R Cgyps1–11Δ::hph HygR | Ref. 9 |

| YRK126 | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418R Cgyps1Δ::hph HygR/pRK935 | Ref. 9 |

| YRK129 | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418R Cgyps1–11Δ::hph HygR/pRK935 | Ref. 16 |

| YRK131 | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418R Cgyps1–11Δ::hph HygR/pRK936 | Ref. 16 |

| YRK228 | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418R Cgyps1Δ::hph HygR | Ref. 9 |

| YRK991 | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418R (BG14) | Ref. 53 |

| YRK1001 | URA3 (BG462) | Ref. 54 |

| YRK1002 | URA3 Cgyps1Δ::hph | Ref. 9 |