Abstract

Background

As mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (MPS IVA) is the most frequent MPS in Colombia, this paper aims to describe its clinical and mutational characteristics in 32 diagnosed patients included in this study.

Methods

Genotyping was completed by amplification and Sanger sequencing of the GALNS gene. The SWISS-model platform was used for bioinformatic analysis, and mutant proteins were generated by homology from the wild-type GALNS code 4FDI template from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database. Docking was performed using the GalNAc6S ligand (PubChem CID: 193456) by AutoDock Vina 1.0 and visualized in PyMOL and LigPlot+.

Results

Eleven variants were identified, and one new pathogenic variant was described in the heterozygous state, which is consistent with genotype c. 319 G> T or p.Ala107Ser. The pathogenic variant c.901G>T or p.Gly301Cys was the most frequent mutation with 51.6% of alleles. Docking revealed affinity energy of −5.9 Kcal/mol between wild-type GALNS and the G6S ligand. Some changes were evidenced at the intermolecular interaction level, and affinity energy for each mutant decreased.

Conclusion

Clinical variables and genotypic analysis were similar to those reported for other world populations. Genotypic data showed greater allelic heterogeneity than those previously reported. Bioinformatics tools showed differences in the binding interactions of mutant proteins with the G6S ligand, in regard the wild-type GALNS.

Keywords: mucopolysaccharidosis IVA, Morquio syndrome, GALNS, lysosomal storage disorder, mutation

Introduction

Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (MPS IVA, Morquio syndrome type A) is a genetic disease with an autosomal recessive inheritance that has been classified as a rare disease. The absence of or partial deficiency of the enzyme N-acetyl-galactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase (GalNAc-6-sulfatase, GALNS, E.C.3.1.6.4), responsible for degradation of glycosaminoglycans keratan sulfate and chondroitin 6-sulfate, leads to the pathological accumulation of these compounds in the body tissues, specifically at bone, cartilage, heart, and lungs.1

The disease prevalence for the general population has been estimated in 1:201,000 live births.2 Frequency in Colombian population was presented by Gómez et al: the overall frequency of all types of MPS was 1.98 per 100,000 live births, MPS type IV being the highest one, with a frequency of 0.68 per 100,000 live births.3

There is also evidence that confirms the disease’s existence in local ancient cultures. Bernal and Briceño performed an examination of pottery collections from Tumaco-La Tolita culture (from the middle of the first millennium BC until the third century AD) and described human figures with features that suggest the presence of MPS type I and IV, along with other inheritable diseases.4

Studies in MPS IVA have been carried out in Colombian population, such as that performed in 1996 by Kato et al. Three missense mutations were identified in a sample of 12 patients; these pathogenic variants were p.Gly301Cys, p.Ser162Phe, and p.Phe69Val.5

As MPS type IV is the most frequent MPS in Colombia, performing an updated study regarding the clinical and mutational characteristics of the patients will help to establish a new reference in MPS IVA in the country.

Materials and methods

The Ethics Committee of the National University of Colombia approved the study, and 32 patients from different regions of the country were included. According to local regulations, the parents or legal guardians of the minors provided their informed consent for participation before being enrolled (assent of the minors was also obtained). The main inclusion criterion referred to patients diagnosed with MPS IVA via clinical, biochemical and genetic/radiological evaluation to measure the activity of the enzyme N-acetyl-galactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase in leukocytes. Data was analyzed based on the Review of clinical presentation and diagnosis of mucopolysaccharidosis IVA published in 2013.6

Exploratory data analysis was performed by using percentages and frequency tables for discrete and categorical variables; continuous variables were analyzed using central tendency and dispersion measures. SPSS (free trial version 21.0) was the statistical software used.

Genomic DNA was extracted by using the Ultraclean® Blood DNA Isolation Kit. Amplification of the 14 exons including the intron-exon boundaries of the GALNS gene was carried out with the primers designed employing the online software Primer 3, as reported by Pajares et al7 and synthesized by Invitrogen (Table S1). Therefore, PCR amplification was done in MyCycler and T100 Bio-Rad® thermocyclers. Sequencing was completed by using an ABI PRISM 3500 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

For reporting gene variants, retrieved electropherograms were analyzed with program BioEdit v7.2.5 Sequence Alignment Editor (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/page2.html; Tom Hall Ibis Therapeutics (a division of Isis Pharmaceuticals), Carlsbad, CA, USA) and compared to the GALNS reference sequence NG_008667. The new variants were classified and analyzed by using the SIFT platforms (http://sift.jcvi.org/www/SIFT_enst_submit.html; Craig Venter Institute, CA, USA), PolyPhen 2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/; Biobyte Solutions, Heidelberg, Germany), Mutation Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org; NCBI 37/Ensembl 69, Schwarz, Cooper, Schuelke, Seelow), PMUT (http://mmb2.pcb.ub.es/PMut/; IRB Barcelona Institute for Research in Biomedicine), PhD-SNP (http://snps.biofold.org/phd-snp/phd-snp.html), and FATHMM (http://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk; University of Bristol Integrative Epidemiology Unit, UK) and taking into account the ACMG recommendations for evaluating the variants.8

Molecular docking was carried out for wild-type GALNS and mutants. As described by Rivera-Colón et al,9 homology modeling was performed using the structure of the protein N-acetyl-galactosamine-6-sulfate-sulfatase. Two structures were utilized for this analysis with accession numbers 4FDI and 4FDJ from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do; Collaborative Research for Structural Bioinformatics: Rutgers and UCSD/SDSC). Modeling was accomplished with a template of wild-type structure of GALNS code 4FDI (due to its 2.2 Å resolution) using the SWISS-model platform. The X, Y, and Z coordinates to be used in AutoDock Tools (version 1.5.6) were calculated with the eFindsite platform (http://brylinski.cct.lsu.edu/efindsite; Louisiana State University). Calculations led to seven options for pocket coordinates, and the authors selected the one with the best confidence interval. Option 1 was chosen for G6S substrate (confidence interval: 0.9580).10 Molecular docking between the enzyme and the ligand was performed in silico; affinity energy (kcal/mol) values were obtained by using AutoDock Vina 1.011 (http://autodock.scripps.edu/news/autodock-vina-1-0-released; The Scripps Research Institute) and AutoDock Tools (Version 1.5.6) (http://mgltools.scripps.edu/downloads; The Scripps Research Institute).

For estimating the energy values for wild-type GALNS bindings and the mutants models, N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate (GalNAc6S; PubChem CID:193456) was used as the ligand molecular docking results were visualized with LigPlot+ (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/Lig-Plus/; EMBL-EBI, Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridgeshire, UK).12

Results

Clinical description

Thirty-two patients from 30 families were included in the study. Families came from different geographical regions: Andean region, which includes the Cundiboyacense Savannah; the Coffee Triangle region; Antioquia and Tolima departments; and Orinoquia, Pacific, and Caribbean regions. Table 1 shows the demographics and characteristics of patients at study entry.

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics of patients at study entry

| Status | Statistics | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Number included | n (%) | 15 (46.9) males; 17 (53.1) females |

| Age at enrollment | Mean (SD), range (years) | 14.5 (10.5) 3–15 |

| Symptom onset age | Mean (SD) | 2.18 (1.44) |

| Symptom onset age distribution | % | |

| Birth–1st year | 28.1 | |

| 1st–3rd year | 62.5 | |

| 3rd – 7th year | 9.4 | |

| Age at diagnosis | Range (years) | <1–29 |

| Diagnosis age distribution | % | |

| Birth–1st year | 3.13 | |

| 1st–3rd year | 40.6 | |

| 3rd–5th year | 31.3 | |

| 5th – 12th year | 18.8 | |

| 20th–29th year | 3 | |

| Most common initial symptoms | % | Pectus carinatum (50) |

| Abnormal gait (40.6) | ||

| Short stature (31.2) | ||

| Most common symptoms at study entry | % | Short stature, pectus carinatum, and genu valgum (100) |

| Abnormal gait (96.9) | ||

| Deformity of elbows (81.3) | ||

| Scoliosis (75) | ||

| Dislocation of wrist (78.3) | ||

| Corneal opacity (63) | ||

| Dental abnormalities (75) | ||

| Dislocation of hip (56.3) | ||

| Hyperlordosis (53.1) | ||

| Hearing loss (46.9) | ||

| Knee osteoarthritis (40.6) | ||

| Cardiac involvement (34.4) | ||

| Hip osteoarthrosis (28.1) | ||

| Dislocation of the cervical spine (21.9) | ||

| Cervical spinal cord compression (18.8) | ||

| Respiratory impairment (15.6) | ||

| Surgery (number of patients) | n (%) | 19 (59.2) |

| Most frequent surgery | % | Cervical spine fixation (11.1) |

| Osteotomies (14.8) | ||

| Myringocentesis (11.1) | ||

| Adenectomy (11.1) | ||

| Tonsillectomy (11.1) | ||

| Phenotypea | n (%) | |

| Severe | 31 (96.88) | |

| Attenuated | 1 (3.12) | |

| Height of male patientsb | % | |

| P3–P10 | 30.7 | |

| P10–P25 | 53.8 | |

| P75 | 15.4 | |

| Height of female patientsb | % | |

| P3–P10 | 14.3 | |

| P25–P50 | 57.1 | |

| P50–P75 | 14.3 | |

| P75–P90 | 7.14 | |

| P90–P97 | 7.14 |

Parents’ consanguinity was reported in 22% of patients (first- and third-degree cousins, uncle–niece relation). As a remarkable matter, both or at least one parents’ geographical ancestries were located in the Cundiboyacense Savannah and Coffee Triangle region (32 patients).

At the time of study initiation, 31.3% (10 patients) were attending weekly enzyme replacement therapy.

Frequency of mutations

Eleven variants were found in this group of patients. Pathogenic variant c.901G> T or p.Gly301Cys was the most frequent with 51.6% of the alleles, followed by mutation c.1156C> T or p.Arg386Cys with 16.1%, and c.485C> T or p.Ser162Phe with 12.9% of the alleles. A single nonsense mutation in the heterozygous state, corresponding to genotype c.974 G> A or p.Trp325X, was also detected, as well as a single heterozygous deletion mutation corresponding to genotype c.853_855delTTC or p.Phe285del was also found (Table 2). It was possible to describe the presence of one new pathogenic variant (not previously reported in the literature) in a heterozygous state, corresponding to genotype c.319 G> T or p.Ala107Ser (Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of clinical and biochemical features of the 32 MPS IVA patients

| Family | Code | Gender | Age of onset (years) | Age at diagnosis (years) | Current age (years) | Height (cm) | Phenotype | Enzymatic activitya (nmol/mg prot/h) | Nucleotide change | Protein change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MPS IVA 001 |

F | 3 | 4.0 | 7 | 92.5 | Severe | 3.9 | c.1156C>T c.1156C>T |

p.R386C p.R386C |

| 2 | MPS IVA 002 |

F | 3 | 3.0 | 26 | 130 | Attenuated | 0.00 | c.491A>C c.860C>T |

p.N164T p.S287L |

| 3 | MPS IVA 003 |

M | 0.5 | 3.0 | 9 | 97 | Severe | 0.12 | c.485C>T c.901G>T |

p.S162F p.G301C |

| 4 | MPS IVA 004 |

F | 2 | 3.0 | 9 | 83 | Severe | 0.01 | c.485C>T c.1156C>T |

p.S162F p.R386C |

| 5 | MPS IVA 005 |

M | 7 | 9.0 | 11 | 92 | Severe | 0.00 | c.860C>T c.901G>T |

p.S287L p.G301C |

| 6 | MPS IVA 006 |

F | 3 | 9.0 | 11 | 93 | Severe | 0.00 | c.901G>T c.1156C>T |

p.G301C p.R386C |

| 6 | MPS IVA 007 |

M | 2 | 2.0 | 2 | 81 | Severe | 0.00 | c.901G>T c.1156C>T |

p.G301C p.R386C |

| 7 | MPS IVA 008 |

F | 2 | 6.0 | 6 | 93 | Severe | 0.06 | c.239C>T c.239C>T |

p.S80L p.S80L |

| 8 | MPS IVA 009 |

M | 2.5 | 3.0 | 15 | 136 | Severe | 0.00 | c.485C>T NF |

p.S162F NF |

| 8 | MPS IVA 010 |

M | 0.5 | 0.5 | 12 | 124 | Severe | 0.00 | c.485C>T NF |

p.S162F NF |

| 9 | MPS IVA 011 |

F | 2 | 4.0 | 10 | 93 | Severe | 3.6 | c.491A>C c.491A>C |

p.N164T p.N164T |

| 10 | MPS IVA 012 |

M | 0.25 | 12.0 | 12 | 100 | Severe | 0.02 | c.485C>T c.485C>T |

p.S162F p.S162F |

| 11 | MPS IVA 013 |

F | 0.5 | 29.0 | 34 | 95 | Severe | 0.00 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 12 | MPS IVA 014 |

M | 5 | 7.0 | 21 | 95 | Severe | 0.07 | c.485C>T c.901G>T |

p.S162F p.G301C |

| 13 | MPS IVA 015 |

M | 1.5 | 3.0 | 5 | 86 | Severe | 0.02 | c.901G>T c.1156C>T |

p.G301C p.R386C |

| 14 | MPS IVA 016 |

F | 0.5 | 5.0 | 5 | 97 | Severe | 0.04 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 15 | MPS IVA 017 |

F | 4 | 7.0 | 38 | 98 | Severe | 0.21 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 16 | MPS IVA 018 |

F | 1 | 4.0 | 4 | 97 | Severe | 0.0 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 17 | MPS IVA 019 |

M | 2 | 2.0 | 24 | 104 | Severe | 0.02 | c.280C>T c.974G>A |

p.R94C p.W325X |

| 18 | MPS IVA 020 |

F | 2 | 2.0 | 5 | 89 | Severe | 0.04 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 19 | MPS IVA 021 |

F | 3 | 5.0 | 23 | 93 | Severe | 0.13 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 20 | MPS IVA 022 |

F | 3 | 4.0 | 6 | 99.5 | Severe | 0.02 | c. 319 G>T c.901G>T |

p. A107S p.G301C |

| 21 | MPS IVA 023 |

M | 0.4 | 5.0 | 34 | 102 | Severe | 0.19 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 22 | MPS IVA 024 |

F | 3 | 4.0 | 8 | 96.5 | Severe | 0.01 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 23 | MPS IVA 025 |

M | 1 | 1.0 | 27 | 102 | Severe | 0.20 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 24 | MPS IVA 026 |

F | 3 | 20.0 | 20 | 80 | Severe | 0.00 | c.1156C>T c.1156C>T |

p.R386C p.R386C |

| 25 | MPS IVA 027 |

M | 2 | 3.0 | 10 | 92 | Severe | 0.01 | c.485C>T c.853_855delTTC |

p.S162F p.F285del |

| 26 | MPS IVA 028 |

M | 3 | 4.0 | 16 | 93 | Severe | 0.00 | c.1156C>T c.1156C>T |

p.R386C p.R386C |

| 27 | MPS IVA 029 |

F | 3 | 3.0 | 3 | 84 | Severe | 0.06 | c.425A>T c.901G>T |

p.H142L p.G301C |

| 28 | MPS IVA 030 |

F | 1.5 | 2.0 | 12 | 98.5 | Severe | 0.03 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 19 | MPS IVA 031 |

M | 0.7 | 2.0 | 4 | 88.8 | Severe | 0.00 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

| 30 | MPS IVA 032 |

M | 2 | 4.0 | 35 | 107 | Severe | 0.00 | c.901G>T c.901G>T |

p.G301C p.G301C |

Note:

Range controls (N = 24): 2.61–15.35.

Abbreviations: MPS IVA, mucopolysaccharidosis IVA; NF, not found; M, male; F, female.

Table 3.

Mutations classification in the gene GALNS

| Nucleotide change | Effect on amino acid | Exon | Mutation Classification | New/Reported | Mutation category | Degree of amino acid conservation | Defined phenotype | Detected alleles (n) | Population | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.239C>T | p.S80L | 2 | Missense | Reported | Active site | Semi-conserved | Severe | 2 | Br | Tomatsu et al26 |

| c.280C>T | p.R94C | 3 | Missense | Reported | Buried | Semi-conserved | Severe | 1 | Cc, Ca, Br | Ogawa et al27 |

| c.319 G>T | p.A107S | 4 | Missense | New | Buried | GALNS-specific | Severe | 1 | Co | Tapiero et al [present study] |

| c.425A>T | p.H142L | 5 | Missense | Reported | Active site | Semi-conserved | Severe | 1 | It | Caciotti et al19 |

| c.485C>T | p.S162F | 5 | Missense | Reported | Buried | Non-conserved | Severe | 8 | Co | Kato et al5 |

| c.491A>C | p.N164T | 5 | Missense | Reported | Buried | GALNS-specific | Indeterminate | 3 | Br | Tomatsu et al28 |

| c.853_855delTTC | p.F285del | 8 | Deletion | Reported | Buried | GALNS-specific | Severe | 1 | It, Am | Tomatsu et al29 |

| c.860C>T | p.S287L | 8 | Missense | Reported | Buried | Semi-conserved | Severe | 2 | Po, Am, Au | Bunge et al30, Tomatsu et al29 |

| c.901G>T | p.G301C | 9 | Missense | Reported | Buried | Non-conserved | Severe | 32 | Co, Mo, Pt, Bt, Sp | Kato et al5, Bunge et al30 |

| c.974 G>A | p.W325X | 9 | Nonsense | Reported | Buried | Non-conserved | Severe | 1 | Ch | Wang et al25 |

| c.1156C>T | p.R386C | 11 | Missense | Reported | Buried | Non-conserved | Severe | 10 | Bt, Jp, It, Mx, Po, Ge, Sp, Tu | Fukuda et al31, Tomatsu et al26 |

Abbreviations: Am, American; Au, Austrian; Br, Brazilian; Bt, British; Ca, Canadian; Cc, Caucasian; Ch, Chinese, Co, Colombian; Ge, German; It, Italian; Jp, Japanese; Mo, Moroccan; Mx, Mexican; Po, Polish; Pt, Portuguese; Sp, Spanish; Tu, Turkish.

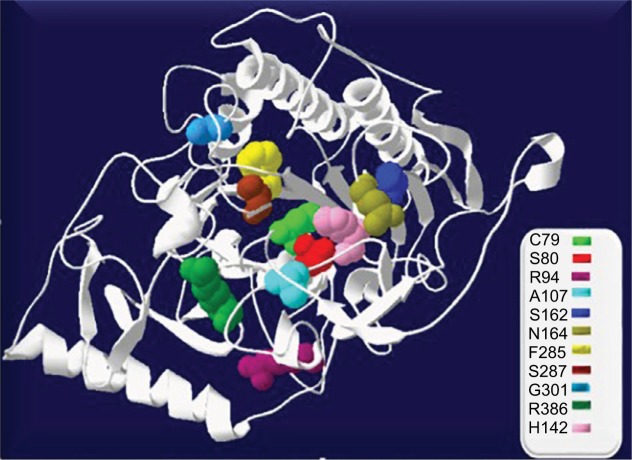

Of these patients, 56.3% were homozygous: (12) p.Gly301Cys, (3) p.Arg386Cys, (1) p.Ser162Phe, (1) p.Asn164Thr, and (1) p.Ser80Leu, while 43.7% exhibited some combination of compound heterozygosity. Two patients (6.3%) belonging to the same family did not express the mutation in the second allele. Other mutations were also reported for the first time in Colombian population: p.Asn164Thr (4.8%); p.Ser80Leu and p.Ser287Leu (3.2%); p.Arg94Cys, p. Ala107Ser, p.His142Leu, and p.Phe 285del (1.6%); and p.Trp325X (1.6%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of mutations in GALNS structure designed in SWISS Protein Data Bank viewer 4.1.0. The active site (C79) is shown in light green spheres.

Bioinformatic analysis

Molecular docking of wild-type GALNS

The active site of GALNS is located in domain 1, and the residues of the active site are p.Asp39, p.Asp40, p.Arg83, p.Tyr108, p.Lys140, p.His142, p.His236, p.Asp288, p.Asn289, p.Lys310, and DHA79.9

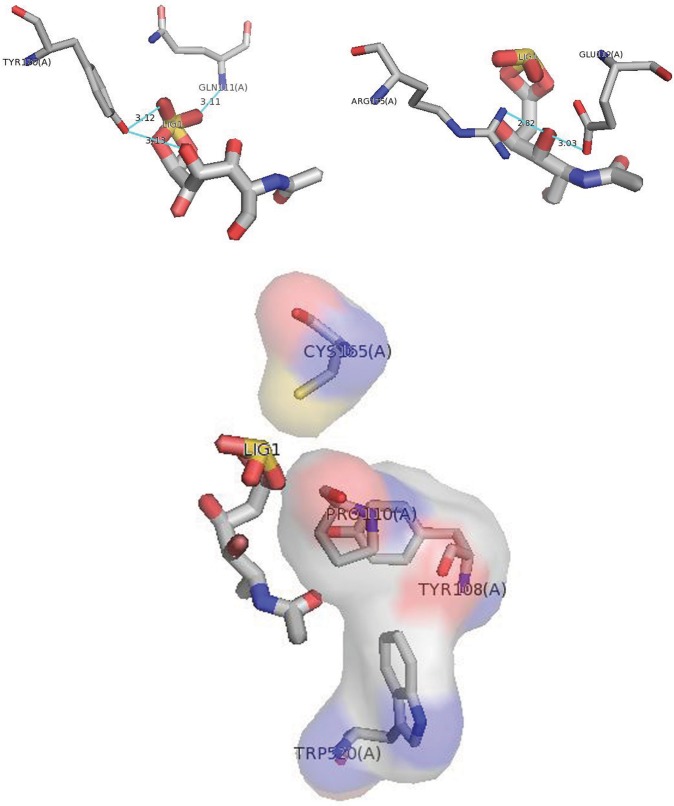

Wild-type GALNS was docked against its molecular substrate N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate (G6S), with an affinity energy of −5.9 kcal/mol. LigPlot+ visualization of docking results identified intermolecular interactions. The O2-sulfate group of N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate interacted with p.Gln111 of GALNS, establishing a hydrogen bond and an electrostatic interaction with p.Tyr108 (Figure 2 and Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Docking of wild-type GALNS and G6S using PyMOL. The most significant interactions are shown: hydrogen bonds, the O2-sulfate group of N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate interacted with p.Gln111 of GALNS, O9 and O7-sulfate of G6S interacted with p.Tyr170, O7 of G6S interacted with p.Arg175 and p.Glu112. Electrostatic interactions with p.Tyr108, p.Cys165, p.Trp520, and p.Pro110.

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) and solvent accessible surface area (ASA)

Each mutant was modeled by homology with SWISS-model using a 4FDI wild-type GALNS template from the RCSB-PDB database, and then the models were refined at PyMOL. Table 4 summarizes the RMSD and ASA measures for each of the models.

Table 4.

Calculated RMSD and ASA for each model of mutant GALNS

| Mutation | Defined phenotype | Energy minimization (kJ/mol) | G6S binding affinity (kcal/mol) | RMSD (Å) C-alpha | ASA (× 103 Å2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type GALNS | −28,700.721 | −5.9 | 18.320 | ||

| p.S80L | Severe | −28,211.699 | −5.3 | 0.222 | 18.318 |

| p.R94C | Severe | −28,379.109 | −5.9 | 0.075 | 18.367 |

| p. A107S | Severe | −28,719.574 | −5.2 | 0.020 | 18.321 |

| p.H142L | Severe | −28,649.404 | −5.1 | 0.068 | 18.329 |

| p.S162F | Severe | −28,459.688 | −5.1 | 0.122 | 18.317 |

| p.N164T | Indeterminate | −28,480.713 | −5.2 | 0.065 | 18.321 |

| p.F285del | Severe | −27,028.111 | −5.9 | 6.906 | 18.335 |

| p.S287L | Severe | −28,352.705 | −5.1 | 0.129 | 18.318 |

| p.G301C | Severe | −28,660.238 | −5.1 | 0.161 | 18.319 |

| p.W325X | Severe | −16,490.084 | −5.0 | 4.062 | 12.773 |

| p.R386C | Severe | −28,407.244 | −5.1 | 0.011 | 18.370 |

Abbreviations: ASA, accessible surface area; RMSD, root mean square deviation.

RMSD was calculated by overlapping all mutant GALNS models with 4FDI wild-type GALNS template. Values of RMSD were obtained from the distances calculated between the atoms from both structures expressed in Angstrom (proteins with high similarity in the structure are close to 1 Å). The variants p.Ser80Leu, p.Arg94Cys, p.Ala107Ser, p.His142Leu, p.Ser162Phe, p.Ser287Leu, p.Gly301Cys, and p.Arg386Cys showed structural alterations with RMSD values below 0.5 Å. As the RMSD value was above 1.0 Å, the deletion and nonsense mutations p.Phe285del and p.Trp325X revealed a change affecting the GALNS structure (Table 4).

ASA was calculated by adding a solvent probe radius of 1.4 Å to the wild-type GALNS, and to the mutant proteins. The ASA result for the wild-type GALNS 18.320 × 103 Å2 was used as a reference for mutants’ comparison. Mutant proteins exhibiting fluctuations at solvent exposure (ASA value decreased) were p.Ser80Leu, p.Ser162Phe, p.Ser287Leu, and p.Gly301Cys. The p.Trp325X mutant showed a substantial decrease in ASA value of 12.773 × 103 Å2 (Table 4).

Discussion

This study evaluated a sample of the Colombian population with clinical, biochemical, and molecular confirmation of MPS IVA, a size sample larger than that assessed by Kato et al in 1997 (10 Colombian families).5 To this date, this is the study with the largest number of genotyped patients reported in Latin America. Thus, it can provide compelling information on the clinical and molecular conditions of MPS IVA in this region.

This clinical and molecular analysis allowed to retrieve and compare data, with extensive available data.13,14 From a clinical perspective, patients showed similar data regarding the age of inclusion when compared to the global registry of MPS IVA, 15.8 years vs. 14.9 years for male patients and 13.3 years vs. 19.1 years for female patients. Also, the age of symptom onset showed similarity with 2.18 years in this study vs. 2.1 years in the global registry, and symptoms like short stature, skeletal abnormalities, and gait disorder were also similar.

Compared to the Morquio A International Registry,13 there were differences regarding phenotype, with a greater number of severely compromised patients, 96.88% vs. 68.4%, that had been reported worldwide. These differences may be explained by underdiagnosis in the attenuated cases, a likelihood to find severe phenotypes in almost all MPS patients of this country.15,16 and also because of our small sample size (32 patients).

When analyzing medical registries, it was observed that patients had fewer interventions compared to data in the registry: cervical fixation 18.8% vs. 51%, myringocentesis 11.1% vs. 33%, and osteotomies 12.5% vs. 26%. This may reflect that medical staff do not have appropriate knowledge of management guidelines for this pathology.13

Mutational profile

From a genotypic approach, results were similar to those documented by Morrone et al in 2014.14 In this study 56.3% of patients were homozygous, 43.7% had some combination of compound heterozygosity, and only 6.3% showed an alteration in one allele, due to the amplification of only involved exon regions and intron-exon boundaries. Morrone et al reported 257 patients (48%) as homozygous, 212 (39%) as compound heterozygous, and 72 (13%) with an alteration in only one identified GALNS allele.14

Regarding missense mutations, prevalence was higher in this study than that reported in the literature, 93.8% vs. 67%. For nonsense mutations, values showed here are lower than those internationally reported, 3.12% vs. 8%, and for deletions 3.12% vs. insertions and deletions 17%. The authors consider that these findings may be attributed to sample size, which was lower in this study compared to international studies, and also to consanguinity among the population (22% in our sample).

Pathogenic variant p.Gly301Cys showed the highest number of alleles (51.6% in 32 patients), and it was found in all cases in severe forms. Kato et al had reported this mutation in 1997 with a prevalence of 68.4% (12 patients) in the first molecular study conducted with Colombian patients.5 This finding confirms the founding effect of this mutation in Colombia.

p.Arg386Cys was the second most frequent pathogenic variant with 16.1%. This has been reported as the most prevalent in the Iberian population7 and therefore easily traceable for Colombia.17 The third one was p.Ser162Phe (12.9%) with a frequency similar to that reported by Kato et al.5

The p.Asn164Thr variant with uncertain significance was found in a patient with attenuated phenotype in the compound heterozygous state (p.Ser287Leu), and also found in another patient with a severe phenotype that showed a homozygous state. This mutation has been reported in the literature for indeterminate phenotypes.13,17,18 It generates a change in the protein with an interruption in the surface avoiding the proper formation of hydrogen bonds, specifically in the domain 1.9 Authors of this study suggest considering this variant with uncertain significance, since it is present in patients with both severe and attenuated phenotypes.

A variant that affects the active site of GALNS c.425A> T p.His142Leu was a missense type reported by Caciotti et al,19 which was found in the patient identified as MPS IVA 029 who exhibited heterozygous state and severe phenotype. This was classified by the authors as deleterious according to the analyses provided by the same prediction software. Notably, p.His142Leu generates a change in the protein, specifically in the domain 1 in the active site. Therefore, it could also be considered as a severe mutation.

One mutation not previously reported was found in heterozygous status in one MPS IVA patient (previous review in databases such as ExAC [http://exac.broadinstitute.org/], 1000 genomes [http://www.internationalgenome.org/], NCBI [http://www.hgmd.org, http://galns.mutdb.org/Database]).20 Patient identified as MPS IVA 022, with a severe phenotype, exhibited the missense mutation c.319G>T p.Ala107Ser, considered by the authors as deleterious according to the analyses provided by PolyPhen 2, FATHMM, and Mutation Taster. This was also found to be neutral using bioinformatic tools such as SIFT software, PMUT, and PhD-SNP. This change affects specifically domain 1 on the protein surface, leaving no space for the side chain. Thus, this could be considered as a probably pathogenic variant, considering the results yielded by the bioinformatics tools mentioned above and the severe phenotype found in the MPS IVA 022 patient included in this study.

Bioinformatic analysis

RMSD let to confirm that the mutant proteins showed a structural alteration, which generates a substantial distance to the wild-type GALNS. However, it was not possible to compare severe and attenuated forms because it was not possible to find an attenuated mutant and only one patient showed the attenuated phenotype.

This study is the first one showing results of bioinformatic analysis of wild-type GALNS and mutant proteins that used the wild-type GALNS structure obtained by X-ray crystallography and deposited in the PDB. For this reason, it is dif ficult to correlate this data with previous studies performed by Sudhakar and Mahalingam and Olarte et al who analyzed RMSD, ASA, and molecular docking with the G6S ligand, since they used as template a GALNS obtained by homology from another kind of sulfatases.21,22

Despite difficulties comparing data presented by Sudhakar and Mahalingam, the authors compared docking results between acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate ligand and wild-type GALNS and found that the model proposed in this study showed an affinity energy level lower than that obtained for wild-type GALNS, findings similar to those presented by Sudhakar and Mahalingam.21

The most relevant intermolecular interactions between wild GALNS and G6S occurred with three hydrogen bonds: one between the O2-sulfate group of G6S with p.Gln111 and the other two between O9 and O7-sulfate of G6S with p.Tyr170; two more electrostatic interactions were present between p.Tyr108 and p.Cys165. Due to these interactions, there were changes in the docking for the p.Gly301Cys mutant, with an affinity energy level of −5.1 kcal mol, which showed only one electrostatic interaction with p.Trp520. Changes were also found for p.Ser287Leu, with an affinity energy level of −5.1 kcal/mol and showing hydrogen bonds with p.Gln311 and p.Asn106 residues. Regarding the undetermined mutant p.Asn164Thr, it showed an affinity energy level of −5.2 kcal/mol, two hydrogen bonds for p.Gln311 and p.Asn106, and two electrostatic interactions with p.Leu78 and p.Ser521. A variant that affects the active site of GALNS p.His142Leu (classified as severe), with affinity energy levels of −5.1 kcal/mol, presented hydrogen bonds interactions with p.Gln311 and p.Asn106 residues, which differs from the wild-type GALNS.

The molecular docking for the new mutant p.Ala107Ser (classified as severe), with affinity energy levels of −5.2 kcal/mol, showed similar behavior when compared to the other mutants classified as severe, since interactions occurred differed from the wild-type GALNS. The p.Ala107Ser exhibited a hydrogen bond interaction with p.Asn106 and an electrostatic interaction with p.Ser521.

Genotype–phenotype correlation

In this study, 96.88% of patients presented with severe phenotypes, two patients showed enzymatic activity above 3.5 nmol/mg prot/h, and one patient (3.12%) with attenuated phenotype exhibited enzymatic activity of 0.0 nmol/mg prot/hr. Severe or attenuated denomination used for phenotypes was based on physical features like height, age, and sex as described by Montaño et al.23 These authors concluded that it is challenging to confirm correlations between clinical and mutational status in MPS IVA.

Study authors consider that these correlations should be strengthened from other approaches, for example, researchers should go beyond anthropometric characteristics and take into account clinical classification with other parameters such as respiratory compromise, mobility in large and small joints, or even visceral compromise. Bioinformatic analysis may also add RMSD values; even interactions of the molecular docking with the particular substrate can contribute to the discussion. This study did not attempt to establish these correlations; however, it provides some clinical and structural data found in the patients exhibiting different mutations in GALNS.

Conclusion

This study presents a global clinical, molecular, and bioinformatic analysis in a group of Colombian patients with MPS IVA. Clinical variables and genotypic analysis were similar to those reported in the global registry for this disease. Genotypic data presented here showed greater allelic heterogeneity than that previously reported by Kato et al in this population,5 Eleven variants were identified, including a new variant in a heterozygous state, corresponding to genotype c. 319 G>T or p.Ala107Ser.

Regarding the bioinformatic analysis of mutant proteins versus wild-type GALNS, this study showed changes in the three-dimensional structure and the molecular docking results, with a decrease in affinity energy levels in kcal/mol and intermolecular interactions for each substratum.

Although genotype–phenotype correlations are very hard to establish in patients with MPS IVA, it is necessary to continue the discussion about these topics and perform regular reviews of clinical and molecular classifications.

Supplementary materials

Docking results of G6S ligand and GALNS interactions using LigPlot+. Hydrogen bonds are represented by green dotted lines and distances between atoms are expressed in Angstroms. Residues involved in hydrophobic interactions are identified (surrounded by a red semicircle). (A) Intermolecular interaction of GALNS model with G6S, affinity energy of −5.9 kcal/mol; (B) intermolecular interaction of p.Asn164Thr model (indeterminate form) with G6S, affinity energy of −5.2 kcal/mol; (C) intermolecular interaction of p.His142Leu model, variant involving a catalytic site residue (severe form) with G6S, affinity energy of −5.1 kcal/mol; (D) intermolecular interaction of p.Ala107Ser model, new variant (severe form) with G6S, affinity energy of −5.2 kcal/mol.

Table S1.

Primers used in PCR

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Fragment size (bp) | % G/C |

|---|---|---|---|

| EXON1 GALNS-F | GTACGCACCTCCTTGGCAATCA | 441 | 54.5 |

| EXON1 GALNS-R | CACTCACGTCGTCCATGAGC | 60 | |

| EXON2 GALNS-F | ACACGCTCTTGGCACCAT | 340 | 56 |

| EXON2 GALNS-R | CCACCCTCCCTGCAGTAGTA | 60 | |

| EXON3 GALNS-F | CGTCTGTCACGCGTCTGT | 294 | 61 |

| EXON3 GALNS-R | ACCAGCGGTACCCCACCT | 67 | |

| EXON4 GALNS-F | CCTGGAAAAATCTTGGGAAGT | 386 | 43 |

| EXON4 GALNS-R | GACACCCTCCTCATTTGGAA | 50 | |

| EXON5 GALNS-F | CTGGAGGGTGCTCGTCTTAC | 347 | 60 |

| EXON5 GALNS-R | ACTTGAGCCCACCAGTGCTA | 55 | |

| EXON6-7 GALNS-F | AAGCCCATGGCTTTGCTG | 698 | 56 |

| EXON6-7 GALNS-R | CCATCTCTGGAGTCAAGCAC | 55 | |

| EXON8 GALNS-F | CTGCCTGATCCATTTGTCAC | 317 | 50 |

| EXON8 GALNS-R | AGAGGGACCCTTCATGCTCT | 55 | |

| EXON9 GALNS-F | CCCTTTGTCCCTATGACCAG | 327 | 55 |

| EXON9 GALNS-R | AGGAGAGCGGTGAGGATGAG | 60 | |

| EXON10 GALNS -F | GTGGGCGTGTGAGCATGTAT | 381 | 55 |

| EXON10 GALNS-R | CCTGTGTCCAGAACCAGGAG | 60 | |

| EXON11 GALNS-F | CTTGCGGGCCTTTTTACTTT | 371 | 45 |

| EXON11 GALNS-R | GAGTTCCTGCCTGTCTCACC | 60 | |

| EXON12 GALNS-F | CTGCTAGGCACAGGCAGAC | 445 | 63 |

| EXON12 GALNS-R | CAAGCACGTGTGGGTATGAA | 50 | |

| EXON13 GALNS-F | ACATGGTCCCAGTGACTGCT | 397 | 55 |

| EXON13 GALNS-R | TGTGCTCTGAGGCACGAG | 61 | |

| EXON14A GALNS-F | TCCCAGCAGCTACTCACTCAG | 524 | 57 |

| EXON14A GALNS-R | GGAGGAGGGTCCTGAAATCT | 55 |

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and their families for their participation in the study.

We would also like to acknowledge the National University of Colombia and BIOMARIN Pharmaceutical for providing administrative assistance and support for the editorial review conducted by Olga Uñate from CER Consulting Services.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Regier DS, Oetgen M, Tanpaiboon P. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IVA. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, Carey WF. Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. JAMA. 1999;281(3):249–254. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gómez AM, García-Robles R, Suárez-Obando F. Estimación de las frecuencias de las mucopolisacaridosis y análisis de agrupamiento espacial en los departamentos de Cundinamarca y Boyacá [Estimation of the mucopolysaccharidoses frequencies and cluster analysis in the Colombian provinces of Cundinamarca and Boyacá] Biomedica. 2012;32(4):602–609. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572012000400015. Article in Spanish. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernal JE, Briceño I. Genetic and other diseases in the pottery of Tumaco-La Tolita culture in Colombia-Ecuador. Clin Genet. 2006;70(3):188–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato Z, Fukuda S, Tomatsu S, et al. A novel common missense mutation G301C in the N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase gene in mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. Hum Genet. 1997;101(1):97–101. doi: 10.1007/s004390050594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendriksz CJ, Harmatz P, Beck M, et al. Review of clinical presentation and diagnosis of mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110(1–2):54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pajares S, Alcalde C, Couce M, et al. Molecular analysis of mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (Morquio A) in Spain. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;106(2):196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivera-Colón Y, Schutsky EK, Kita AZ, Garman SC. The structure of human GALNS reveals the molecular basis for mucopolysaccharidosis IV A. J Mol Biol. 2012;423(5):736–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moult J. A decade of CASP: progress, bottlenecks and prognosis in protein structure prediction. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15(3):285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2009;31(2):455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laskowski RA, Swindells MB. LigPlot+: multiple ligand–protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51(10):2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montaño AM, Tomatsu S, Gottesman GS, Smith M, Orii T. International Morquio A Registry: clinical manifestation and natural course of Morquio A disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30(2):165–174. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0529-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrone A, Caciotti A, Atwood R, et al. Morquio a syndrome-associated mutations: a review of alterations in the GALNS gene and a new locus-specific database. Hum Mutat. 2014;35(11):1271–1279. doi: 10.1002/humu.22635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pineda T, Marie S, Gonzalez J, et al. Genotypic and bioinformatic evaluation of the alpha-L-iduronidase gene and protein in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type I from Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2014;1(4):468–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galvis J, González J, Uribe A, Velasco H. Deep genotyping of the IDS gene in Colombian patients 2 with Hunter syndrome. JIMD Rep. 2015;19:101–109. doi: 10.1007/8904_2014_376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomatsu S, Dieter T, Schwartz IV, et al. Identification of a common mutation in mucopolysaccharidosis IVA: correlation among genotype, phenotype, and keratan sulfate. J Hum Genet. 2004;49(9):490–494. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee NH, Cho SY, Maeng SH, et al. Clinical, radiologic, and genetic features of Korean patients with mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. Korean J Pediatr. 2012;55(11):430–437. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2012.55.11.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caciotti A, Tonin R, Rigoldi M, et al. Optimizing the molecular diagnosis of GALNS : novel methods to define and characterize Morquio-A syndrome-associated mutations. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(3):357–368. doi: 10.1002/humu.22751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson K. Evaluation of Select Publicly Available in Silico Methods for Predicting Functional Effects of Missense Mutations in the GALNS Gene [master’s thesis] San Rafael, CA: Dominican University of California; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sudhakar SC, Mahalingam K. Structural and functional analysis of N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase using bioinformatics tools: insight into Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. J Pharm Res. 2011;4(11):3958–3962. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olarte S, Rodríguez-López A, Almeciga-Diaz CJ. Computational approach for the design of a less immunogenic GALNS enzyme. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;111(2):S82. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montaño AM, Tomatsu S, Brusius A, Smith M, Orii T. Growth charts for patients affected with Morquio A disease. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2008;146A(10):1286–1295. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomatsu S, Montaño AM, Nishioka T, et al. Mutation and polymorphism spectrum of the GALNS gene in mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (Morquio A) Hum Mutat. 2005;26(6):500–512. doi: 10.1002/humu.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Zhang W, Wang Y, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA mutations in Chinese patients: 16 novel mutations. J Hum Genet. 2010;55(8):534–540. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomatsu S, Fukuda S, Cooper A, et al. Fourteen novel mucopolysaccharidosis IVA producing mutations in GALNS gene. Hum Mutat. 1997;10:368–375. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)10:5<368::AID-HUMU6>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogawa T, Tomatsu S, Fukuda S, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA: screening and identification of mutations of the N-acetyl galactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:341–349. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomatsu S, Nishioka T, Montano AM, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA: identification of mutations and methylation study in GALNS gene. J MedGenet. 2004c;41:e98. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.018010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomatsu S, Filocamo M, Orii KO, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA: (Morquio A): identification of novel common mutations in the N-acetyl-galactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase (GALNS) gene in Italian patients. Hum Mutat. 2004d;24:187–188. doi: 10.1002/humu.9265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bunge S, Kleijer WJ, Tylki-Szymanska A, et al. Identification of 31 novel mutations in the N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfatase gene reveals excessive allelic heterogeneity among patients with Morquio A syndrome. Hum Mutat. 1997;10:223–232. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)10:3<223::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukuda S, Tomatsu S, Masuno M, et al. submicroscopic deletion of 16q24.3 and a novel R386C mutation of N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfatase gene in a classical Morquio disease. Hum Mutat. 1996a;7:123–134. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)7:2<123::AID-HUMU6>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Docking results of G6S ligand and GALNS interactions using LigPlot+. Hydrogen bonds are represented by green dotted lines and distances between atoms are expressed in Angstroms. Residues involved in hydrophobic interactions are identified (surrounded by a red semicircle). (A) Intermolecular interaction of GALNS model with G6S, affinity energy of −5.9 kcal/mol; (B) intermolecular interaction of p.Asn164Thr model (indeterminate form) with G6S, affinity energy of −5.2 kcal/mol; (C) intermolecular interaction of p.His142Leu model, variant involving a catalytic site residue (severe form) with G6S, affinity energy of −5.1 kcal/mol; (D) intermolecular interaction of p.Ala107Ser model, new variant (severe form) with G6S, affinity energy of −5.2 kcal/mol.

Table S1.

Primers used in PCR

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Fragment size (bp) | % G/C |

|---|---|---|---|

| EXON1 GALNS-F | GTACGCACCTCCTTGGCAATCA | 441 | 54.5 |

| EXON1 GALNS-R | CACTCACGTCGTCCATGAGC | 60 | |

| EXON2 GALNS-F | ACACGCTCTTGGCACCAT | 340 | 56 |

| EXON2 GALNS-R | CCACCCTCCCTGCAGTAGTA | 60 | |

| EXON3 GALNS-F | CGTCTGTCACGCGTCTGT | 294 | 61 |

| EXON3 GALNS-R | ACCAGCGGTACCCCACCT | 67 | |

| EXON4 GALNS-F | CCTGGAAAAATCTTGGGAAGT | 386 | 43 |

| EXON4 GALNS-R | GACACCCTCCTCATTTGGAA | 50 | |

| EXON5 GALNS-F | CTGGAGGGTGCTCGTCTTAC | 347 | 60 |

| EXON5 GALNS-R | ACTTGAGCCCACCAGTGCTA | 55 | |

| EXON6-7 GALNS-F | AAGCCCATGGCTTTGCTG | 698 | 56 |

| EXON6-7 GALNS-R | CCATCTCTGGAGTCAAGCAC | 55 | |

| EXON8 GALNS-F | CTGCCTGATCCATTTGTCAC | 317 | 50 |

| EXON8 GALNS-R | AGAGGGACCCTTCATGCTCT | 55 | |

| EXON9 GALNS-F | CCCTTTGTCCCTATGACCAG | 327 | 55 |

| EXON9 GALNS-R | AGGAGAGCGGTGAGGATGAG | 60 | |

| EXON10 GALNS -F | GTGGGCGTGTGAGCATGTAT | 381 | 55 |

| EXON10 GALNS-R | CCTGTGTCCAGAACCAGGAG | 60 | |

| EXON11 GALNS-F | CTTGCGGGCCTTTTTACTTT | 371 | 45 |

| EXON11 GALNS-R | GAGTTCCTGCCTGTCTCACC | 60 | |

| EXON12 GALNS-F | CTGCTAGGCACAGGCAGAC | 445 | 63 |

| EXON12 GALNS-R | CAAGCACGTGTGGGTATGAA | 50 | |

| EXON13 GALNS-F | ACATGGTCCCAGTGACTGCT | 397 | 55 |

| EXON13 GALNS-R | TGTGCTCTGAGGCACGAG | 61 | |

| EXON14A GALNS-F | TCCCAGCAGCTACTCACTCAG | 524 | 57 |

| EXON14A GALNS-R | GGAGGAGGGTCCTGAAATCT | 55 |