Abstract

Background

Changes in substance use patterns stemming from opioid misuse, ongoing drinking problems, and marijuana legalization may result in new populations of patients with substance use disorders (SUDs) using emergency department (ED) resources. This study examined ED admission trends in a large sample of patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders in an integrated health system.

Methods

In a retrospective design, electronic health record (EHR) data identified patients with ≥1 of 3 common SUDs in 2010 (n = 17,574; alcohol, marijuana, or opioid use disorder) and patients without SUD (n = 17,574). Logistic regressions determined odds of ED use between patients with SUD versus controls (2010–2014); mixed-effect models examined 5-year differences in utilization; moderator models identified subsamples for which patients with SUD may have a greater impact on ED resources.

Results

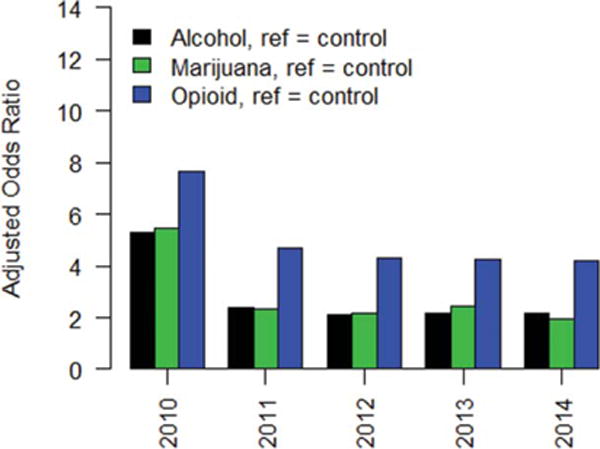

Odds of ED use were higher at each time point (2010–2014) for patients with alcohol (odds ratio [OR] range: 5.31–2.13, Ps < .001), marijuana (OR range: 5.45–1.97, Ps < .001), and opioid (OR range: 7.63–4.19, Ps < .001) use disorders compared with controls; odds decreased over time (Ps < .001). Patients with opioid use disorder were at risk of high ED utilization; patients were 7.63 times more likely to have an ED visit in 2010 compared with controls and remained 5.00 (average) times more likely to use ED services. ED use increased at greater rates for patients with alcohol and opioid use disorders with medical comorbidities relative to controls (Ps < .045).

Conclusions

ED use is frequent in patients with SUDs who have access to private insurance coverage and integrated medical services. ED settings provide important opportunities in health systems to identify patients with SUDs, particularly patients with opioid use disorder, to initiate treatment and facilitate ongoing care, which may be effective for reducing excess medical emergencies and ED encounters.

Keywords: Access/demand/utilization of services, administrative data uses, managed care organizations, mental health, substance abuse

Introduction

The United States faces a dynamic landscape regarding marijuana, opioids, and alcohol. Concerns about these substances center around opioid misuse,1,2 an ongoing high prevalence of alcohol-related harms,3 and the liberalization of marijuana use policies.4,5 Not surprisingly, excessive use of alcohol, marijuana, and prescription opioids increases risk of addiction and developing associated substance use disorders (SUDs).6 In 2014, 17.0 million people 12 years of age or older were diagnosed with alcohol use disorder, 4.2 million had a marijuana use disorder, and 1.9 million had a disorder related to the nonmedical use of prescription pain relievers.6 In recent years, heroin and other potent opioids such as fentanyl have made increasing contributions to rising opioid overdoses.7 In addition, persons with alcohol, marijuana, or opioid use disorder are more likely to have comorbid conditions, which worsen prognosis, contribute to poor health,8 and can lead to inappropriate health service use.9,10

Utilization of emergency department (ED) resources are 50% to 100% higher for patients with SUD compared with patients without SUD.9–12 In addition to acute medical emergencies, ED use may be indicative of poor health, unmet service need, or inappropriate use of health care.9–14 To date, studies have found most SUD-related ED visits are associated with alcohol,9,10,13 and frequently document ED-based treatments have focused on alcohol to the exclusion of other drugs.4,10 Yet, ED visits associated with the misuse of opioids and marijuana are common,4,10,11 and considerable SUD-related ED visits involve concurrent or other drug use.4 In addition, alcohol and opioid use disorders are among the most severe SUD diagnoses in terms of their negative impact on health, and evidence continues to emerge about the adverse health effects associated with marijuana use disorder.4,15,16 Thus, the study of ED trends among patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders is important.

High rates of SUD-related clinical emergencies and associated ED visits are a persistent barrier to improving health outcomes in this population.9,10 Thus, a study that seeks to identify how patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders use ED resources is important, to potentially inform more specific ED-based treatment efforts (e.g., identification of SUD, ED-initiated brief intervention for substance use, and referral to follow-up care). This study examined ED trends across patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders, and controls, over time in a large integrated health care system in which all patients have insurance coverage to access health care. Using electronic health record (EHR) data, we aimed to (1) determine the odds of having an ED visit each year from 2010 to 2014 for patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders relative to controls without these conditions; (2) evaluate differences in ED use between controls and those with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders over 5 years; and (3) explore subsamples for which patients with SUD (vs. controls) may have a greater impact on ED resources.

Methods

Setting

Kaiser Permanente of Northern California (KPNC) is a nonprofit, integrated health care delivery system with 4 million members, who account for 44% of the commercially insured population in the region. KPNC operates over 54 outpatient clinics and employs more than 7000 physicians. About 88% of members are commercially insured, 28% have Medicare, and 10% have Medicaid coverage. All patients were selected from the KPNC membership.

Data source and study participants

We used secondary EHR data for this database-only study. These data were used to identify all health plan members who (1) were aged 18 or older, (2) who had a visit to a KPNC facility in 2010, and (3) had a recorded ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision) diagnosis of alcohol, marijuana, or opioid abuse or dependence in 2010. The first mention for each ICD-9 diagnosis of alcohol, marijuana, or opioid use disorder recorded from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2010, were included; patients in the sample could have multiple diagnoses (e.g., SUD groups were not mutually exclusive). We also included all current or existing SUD diagnosis that were additionally documented for patients with alcohol, marijuana, or opioid use disorder during health plan visits in 2010 (see Appendix 1 for included ICD-9 codes). Within KPNC, SUD and other behavioral health diagnoses (e.g., major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, etc.) can be assigned to patients in any clinic setting, e.g., primary care or any specialty care clinic. Diagnoses can be assigned by physicians or any other qualified health care provider who is directly evaluating a patient. All diagnoses are captured through ICD-9 codes.

EHR data were used to identify control patients who did not have current or existing SUDs or other behavioral health diagnoses. Control patients were selected for all unique patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders and matched one-to-one on gender, age, and medical home facility. This accounted for differences in services, types of behavioral health conditions, or unobservable differences by geographic location. To control for varying lengths of membership, participants were required to be KPNC members for at least 80% of the study (at least 4 out of the 5 years studied17).

The final analytical sample consisted of 35,148 patients: 12,411 with alcohol use disorder, 2752 with marijuana use disorder, 2411 with opioid use disorder, and 17,574 controls. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute.

Measures

Patient characteristics

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, and clinical diagnoses were extracted from the EHR. Race/ethnicity consisted of 5 categories: white, black, Hispanic, Asian, and other. Psychiatric and SUD diagnoses were determined from ICD-9 codes documented during health system visits in 2010 and included current and existing diagnoses. Co-occurring medical conditions were measured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index18; higher scores indicate greater medical burden.

ED utilization

ED data from 2010 through 2014 was extracted from the EHR. For each year, dichotomous ED utilization measures were defined (1 = present, 0 = else). ED encounters both within and outside of KPNC for the study duration were included to account for members who may have used ED resources outside the KPNC health care system.

Data analysis

Frequencies and means were used to characterize the sample. We then employed χ2 tests (categorical variables) and independent t tests (continuous variables) to identify differences between the controls and those with alcohol, marijuana, or opioid use disorder. A series of logistic regression analyses were computed for each year (2010, 2011, 2013, and 2014) to compare the odds of having ED visits for each SUD group relative to controls. All models adjusted for gender (1 = men, 0 = else), race/ethnicity (white = reference, Hispanic, Asian, black, “other”), age (18–29 = reference, 30–39, 40–49, 50+), and medical comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index score).

Longitudinal analyses were conducted within a generalized mixed-effects growth model framework, using penalized-quasi-likelihood estimation for computing parameter estimates of binary outcomes. This approach is a form of hierarchical linear modeling for repeated measures data, where multiple measurement occasions are nested within persons.19 These analyses began with unconditional growth models predicting ED utilization from time (coded: 0 = 2010; 1 = 2011; 2 = 2012; 3 = 2013; 4= 2014) to examine the 5-year patterns of ED utilization for each SUD group. We then constructed conditional growth models predicting ED use from time and a time × SUD group interaction (reference = control), to examine differences between alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorder patients and controls on ED use over 5 years. For these conditional growth models, the time × SUD group interaction indicates differences in the rates of ED utilization between patients with versus without SUD over 5 years, controlling for person-level differences (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity, and medical comorbidity). Finally, we computed a series of moderator analyses employing mixed-effects moderator models to explore subsamples for which patients with SUD (vs. controls) may have a greater impact on ED resources over time. Moderator model analyses proceeded by examining potential differences in the association among patients with SUD (reference = controls) and ED use by age, gender, race/ethnicity, and medical comorbidity by time. Analyses were run in R version 3.3.120 and statistical significance was defined at P < .05.

Results

Sample characteristics

Overall, the sample was 35.5% women, 60.0% white, 16.1% Hispanic, 11.0% Asian, 8.6% black, and 4.0% other race/ethnicity. Patients were 37 years old on average. Differences in the characteristics among patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders and the controls are reported in Table 1. Compared with controls, more patients with alcohol, marijuana, or opioid use disorder were white or black; more controls were Asian, Hispanic, or had a race/ethnicity categorized as “other” compared with those with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorder with few exceptions. In addition, compared with controls, patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders had greater medical comorbidities (Table 1), and co-occurring mental health and substance use conditions were common (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Variable | Alcohol use disorder (n = 12,411) % |

Control (n = 12,411) % |

P | Marijuana use disorder (n = 2752 % |

Control (n = 2752) % |

P | Opioid use disorder (n = 2411) % |

Control (n = 2411) % |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 65.9 | 53.1 | <.001 | 60.7 | 46.1 | <.001 | 75.1 | 54.8 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 16.4 | 16.1 | .429 | 15.7 | 18.8 | .002 | 13.3 | 17.5 | <.001 |

| Asian | 6.3 | 18.2 | <.001 | 5.1 | 20.2 | <.001 | 2.6 | 15.1 | <.001 |

| Black | 8.3 | 7.6 | .061 | 15.6 | 8.7 | <.001 | 7.4 | 7.3 | .999 |

| Unknown | 2.8 | 4.8 | <.001 | 2.6 | 5.9 | <.001 | 1.3 | 4.9 | <.001 |

| Women | 31.3 | 31.3 | ns | 35.8 | 35.7 | ns | 54.8 | 54.8 | ns |

| Age (years), M (SD) | 49.6 (15.2) | 49.8 (15.3) | ns | 36.4 (15.7) | 36.8 (15.2) | ns | 44.7 (14.6) | 45.1 (14.6) | ns |

| Medical (CCIa score), M (SD) | 0.44 (0.97) | 0.36 (0.87) | <.001 | 0.33 (0.89) | 0.20(0.63) | <.001 | 0.55 (1.11) | 0.26 (0.72) | <.001 |

| ED utilization | |||||||||

| 2010 | 49.1 | 15.5 | <.001 | 53.4 | 16.6 | <.001 | 59.0 | 13.8 | <.001 |

| 2011 | 29.9 | 14.5 | <.001 | 33.3 | 16.1 | <.001 | 47.4 | 14.5 | <.001 |

| 2012 | 28.7 | 15.3 | <.001 | 31.8 | 16.2 | <.001 | 46.3 | 15.5 | <.001 |

| 2013 | 28.6 | 14.9 | <.001 | 31.1 | 14.3 | <.001 | 45.3 | 15.1 | <.001 |

| 2014 | 28.8 | 15.3 | <.001 | 29.7 | 16.0 | <.001 | 42.9 | 13.6 | <.001 |

Note. Medical = medical comorbidity; ED = emergency department. Patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders were matched to controls by gender, age, and medical home facility; ns = nonsignificant P values were equal to 1 for gender and age as patients were matched based on these variables.

CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; higher mean scores indicate greater medical disease burden.

Table 2.

Substance use and psychiatric comorbidity among patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders.

| Variable | Alcohol use disorder (n = 12,411) |

Marijuana use disorder (n = 2752) |

Opioid use disorder (n = 2411) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Any psychiatric conditiona | 5201 | 41.9 | 1578 | 57.3 | 1713 | 71.0 |

| Depression | 3834 | 30.8 | 1106 | 40.1 | 1357 | 56.2 |

| Anxiety | 2689 | 21.6 | 859 | 31.2 | 996 | 41.3 |

| Bipolar | 572 | 4.6 | 287 | 10.4 | 226 | 9.3 |

| Schizophrenia | 111 | 0.8 | 90 | 3.2 | 37 | 1.5 |

| Other psychoses | 221 | 1.7 | 157 | 5.7 | 70 | 2.9 |

| Personality disorders | 276 | 2.2 | 142 | 5.1 | 156 | 6.4 |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 209 | 1.6 | 152 | 5.5 | 104 | 4.3 |

| Dementia | 124 | 0.9 | 14 | 0.5 | 29 | 1.2 |

| Autism | 16 | 0.1 | 8 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.2 |

| >1 Psychiatric condition | 3103 | 25.0 | 766 | 27.8 | 812 | 33.6 |

| >2 Psychiatric conditions | 1648 | 13.2 | 535 | 19.4 | 652 | 27.0 |

| Any substance use disorderb | 1681 | 13.5 | 1216 | 44.1 | 833 | 34.5 |

| Alcohol use disorder | — | — | 907 | 32.9 | 499 | 20.6 |

| Marijuana use disorder | 907 | 7.3 | — | — | — | — |

| Opioid use disorder | 499 | 4.0 | 272 | 9.8 | 272 | 11.2 |

| Cocaine use disorder | 293 | 2.3 | 157 | 5.7 | 76 | 3.1 |

| Barbiturate use disorder | 182 | 1.4 | 78 | 2.8 | 246 | 10.2 |

| Amphetamine use disorder | 302 | 2.4 | 210 | 7.6 | 115 | 4.7 |

| Hallucinogen use disorder | 14 | 0.1 | 26 | 0.9 | 10 | 0.4 |

| >1 Substance use disorder | 10,730 | 86.4 | 1536 | 55.8 | 1578 | 65.4 |

| >2 Substance use disorders | 1278 | 10.2 | 888 | 32.2 | 544 | 22.5 |

1 = any psychiatric comorbidity; 0 = else.

1 = any nonalcohol, nonmarijuana, or nonopioid substance use disorder; 0 = else.

Patterns of emergency department utilization

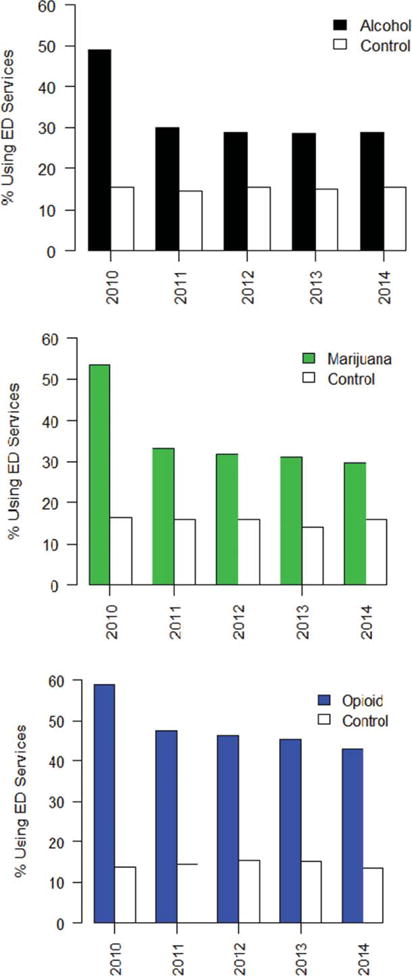

ED utilization patterns among patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders and controls were examined during each year (2010–2014). At each time point, more patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders used ED services relative to controls (Table 1; Figure 1); ED use decreased over the follow-up. Similarly, compared with controls, patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders were more likely to have an ED visit at each time point, and these odds decreased from 2010 to 2014 (Figure 2). Patients with opioid use disorder were at risk of high ED utilization, with these patients being 7.63 times more likely of having an ED visit in 2010 versus controls, and remaining 5.00 (average) times more likely to have ED visits over time.

Figure 1.

Emergency department visits among patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders compared with controls for all years 2010 to 2014.

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratios of emergency department visits among patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders compared with controls for all years 2010 to 2014.

As shown in Table 3, ED (B = −0.01 [95% confidence interval, CI = 0.978, 0.987], P < .001) use significantly declined in the sample over 5 years. Patients with alcohol use disorder (B = 0.24 [95% CI = 1.247, 1.311], P < .001) were more likely than controls to have an ED visit in 2010 and then subsequently demonstrated a faster decline in ED use (B = −0.03 [95% CI = 0.951, 0.971], P < .001) relative to controls over 5 years. Patients with marijuana (B = 1.41 [95% CI = 3.569, 4.702], P < .001) and opioid (B = 1.82 [95% CI = 5.387, 7.134], P < .001) use disorders were also more likely than controls to have an ED visit in 2010, and then those with marijuana (B = −0.23 [95% CI = 0.747, 0.837], P < .001) and opioid (B = −0.12 [95% CI = 0.830, 0.930], P < .001) use disorders exhibited a faster decline in ED service use compared with controls over time (Table 3).

Table 3.

Longitudinal predictors of emergency department utilization.

| Variable | Emergency department utilization

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | SE | P | |

| Unconditional Growth Model | ||||

| Time | −0.01 | (0.978, 0.987) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Conditional Growth Model—Alcohol | ||||

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||

| Hispanic | −0.01 | (0.981, 1.006) | 0.01 | .325 |

| Asian | 0.01 | (1.004, 1.019) | 0.01 | .002 |

| Black | −0.02 | (0.962, 0.984) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Other | 0.02 | (1.019, 1.038) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Ageb | ||||

| 30–39 | −0.01 | (0.985, 1.011) | 0.01 | .752 |

| 40–49 | −0.01 | (0.981, 1.005) | 0.01 | .269 |

| 50+ | −0.01 | (0.982, 1.006) | 0.01 | .340 |

| Female | 0.02 | (1.013, 1.045) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Medical comorbidityc | 0.05 | (1.053, 1.068) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Alcohold | 0.24 | (1.247, 1.311) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Time × Alcohold | −0.03 | (0.951, 0.971) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Moderated Growth Modele—Alcohol | ||||

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||

| Time × Hispanic × Alcohol | −0.01 | (0.977, 1.010) | 0.01 | .641 |

| Time × Asian × Alcohol | −0.01 | (0.980, 0.999) | 0.01 | .967 |

| Time × Black × Alcohol | −0.01 | (0.971, 0.999) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Time × Other × Alcohol | 0.05 | (1.014, 1.043) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Ageb | ||||

| Time × 30–39 × Alcohol | 0.01 | (1.005, 1.034) | 0.01 | .319 |

| Time × 40–49 × Alcohol | 0.01 | (0.993, 1.021) | 0.01 | .412 |

| Time × 50+ × Alcohol | 0.01 | (1.004, 1.035) | 0.01 | .406 |

| Female | ||||

| Time × Female × Alcohol | 0.06 | (1.050, 1.093) | 0.01 | .380 |

| Medical comorbidityc | ||||

| Time × Medical × Alcohol | 0.01 | (0.998, 1.017) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Conditional Growth Model—Marijuana | ||||

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||

| Hispanic | −0.08 | (0.863, 0.987) | 0.03 | .019 |

| Asian | 0.07 | (1.034, 1.119) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Black | −0.14 | (0.817, 0.909) | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Other | 0.18 | (1.133, 1.274) | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Ageb | ||||

| 30–39 | 0.01 | (0.958, 1.068) | 0.02 | .676 |

| 40–49 | −0.07 | (0.883, 0.977) | 0.02 | .004 |

| 50+ | −0.08 | (0.882, 0.965) | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Female | 0.07 | (0.992, 1.167) | 0.04 | .078 |

| Medical comorbidityc | 0.29 | (1.290, 1.405) | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Marijuanad | 1.41 | (3.569, 4.702) | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Time × Marijuanad | −0.23 | (0.747, 0.837) | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Moderated Growth Modele—Marijuana | ||||

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||

| Time × Hispanic × Marijuana | 0.01 | (0.980, 1.027) | 0.01 | .792 |

| Time × Asian × Marijuana | −0.01 | (1.044, 1.114) | 0.01 | .378 |

| Time × Black × Marijuana | −0.01 | (0.970, 1.012) | 0.01 | .671 |

| Time × Other × Marijuana | −0.01 | (0.961, 1.081) | 0.01 | .375 |

| Ageb | ||||

| Time × 30–39 × Marijuana | −0.01 | (0.967, 1.022) | 0.02 | .655 |

| Time × 40–49 × Marijuana | 0.01 | (0.990, 1.041) | 0.01 | .251 |

| Time × 50+ × Marijuana | −0.01 | (0.975, 1.020) | 0.01 | .819 |

| Female | ||||

| Time × Female × Marijuana | 0.03 | (0.993, 1.156) | 0.01 | .082 |

| Medical comorbidityc | ||||

| Time × Medical × Marijuana | 0.03 | (0.998, 1.066) | 0.01 | .069 |

| Conditional Growth Model—Opioid | ||||

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||

| Hispanic | −0.08 | (0.851, 0.986) | 0.03 | .019 |

| Asian | 0.14 | (1.107, 1.211) | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Black | −0.21 | (0.760, 0.858) | 0.03 | <.001 |

| Other | 0.20 | (1.147, 1.306) | 0.30 | <.001 |

| Ageb | ||||

| 30–39 | 0.05 | (0.996, 1.116) | 0.02 | <.001 |

| 40–49 | −0.10 | (0.852, 0.949) | 0.02 | .069 |

| 50+ | −0.08 | (0.875, 0.971) | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Female | 1.82 | (1.221, 1.426) | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Medical comorbidityc | 0.30 | (1.309, 1.415) | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Opioidd | 1.82 | (5.387, 7.134) | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Time × Opioidd | −0.12 | (0.830, 0.930) | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Moderated Growth Modele—Opioid | ||||

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||

| Time × Hispanic × Opioid | −0.01 | (0.861, 1.018) | 0.01 | .281 |

| Time × Asian × Opioid | 0.01 | (1.055, 1.160) | 0.01 | .591 |

| Time × Black × Opioid | −0.01 | (0.709, 0.819) | 0.01 | .551 |

| Time × Other × Opioid | 0.01 | (1.055, 1.160) | 0.01 | .371 |

| Ageb | ||||

| Time × 30–39 × Opioid | −0.01 | (0.890, 1.118) | 0.01 | .670 |

| Time × 40–49 × Opioid | −0.01 | (0.891, 1.100) | 0.01 | .891 |

| Time × 50+ × Opioid | −0.01 | (1.045, 1.273) | 0.01 | .092 |

| Female | ||||

| Time × Female × Opioid | −0.01 | (0.900, 1.177) | 0.01 | .670 |

| Medical comorbidityc | ||||

| Time × Medical × Opioid | 0.02 | (0.977, 1.179) | 0.01 | .045 |

Note. Alcohol = patients with alcohol use disorder; Marijuana = patients with marijuana use disorder; Opioid = patients with opioid use disorder.

Reference = white.

Reference = ages 18–29.

Charlson Comorbidity Index; higher scores indicate greater medical disease burden.

Reference = controls.

Only a priori moderated effects of interested are presented to reduce visual clutter.

Subsamples for which having a SUD may have a greater impact on ED visits were investigated. A greater increase in ED use was observed for patients with medical comorbidities who had alcohol (B = 0.01 [95% CI = 0.998, 1.017], P < .001) or opioid (B = 0.02 [95% CI = 0.977, 1.179], P = .045) use disorder compared with controls with medical comorbidities. Although not significant, a trend increase in ED use was found for patients with medical comorbidities who had marijuana use disorder (B = 0.03 [95% CI = 0.998, 1.066], P = .069) compared with controls with medical comorbidities. Compared with black controls, a greater decline in ED use was observed among black patients with alcohol use disorder (B = −0.01 [95% CI = 0.971, 0.999], P < .001). A greater increase in ED use was observed among patients in the “other” race/ethnicity who had alcohol use disorder (B = 0.05 [95% CI = 1.014, 1.043], P < .001) compared with controls who had a race/ethnicity characterized as other. No other significant interactions were observed (Table 3).

Discussion

Alcohol, marijuana, and opioids frequently take center stage in public policy and debate as concerns remain focused around opioid misuse and overdose,1,2 ongoing drinking problems,3 and liberalization of marijuana use policies.4,5 Persons who excessively use these substances face the risk of developing an associated SUD,6 which can have considerable implications for patient health and health systems,15 in part by contributing to high use of ED services.9–12 Thus, we examined how patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders, and controls, used ED resources over time in a large health care system.

Similar to studies conducted in the general population and other health systems,6,21–23 alcohol use disorder was diagnosed the most frequently, followed by marijuana use disorder, and opioid use disorder, and the rates of co-occurring medical, psychiatric, and SUD were substantial in each. Because these conditions worsen prognosis, lead to high morbidity,21,22,24 and can contribute to inappropriate service use,9,10 it is not surprising we found that patients with these disorders consistently had greater likelihood of ED use relative to controls. ED visits were the highest among patients with opioid use disorder, followed by those with marijuana and alcohol use disorders, which is contrary to prior work that has documented most SUD-related ED visits are associated with alcohol use disorder.9,10,13 This difference could reflect the effects of changing marijuana use disorder patterns and an overall high morbidity among patients with opioid disorder, which may have large effects on health system resources.1,2,4,6,8–10 Most ED-based treatments focus on alcohol to the exclusion of other drugs,4,10 and since our data suggest that ED visits are also frequent among patients with marijuana and opioid use disorders, these patients may be at risk for having unmet or unidentified treatment needs. Consequently, building on ED-based treatments for patients with alcohol use disorder,4,10 it will be important for future studies to extend these treatments to patients with opioid and marijuana use disorders, to reduce medical emergencies and improve patient health in this population.

Patients with opioid use disorder constituted a modest proportion of the sample, and these patients consistently had high odds of ED use. Similar to this, previous studies report that patients with opioid use disorder are overrepresented in ED settings.1,12,25,26 This could be due to the individual or combined effects of complex medical conditions, injury, or overdose,26 which have large impact on the burden of disease and are some of the more persistent barriers to improving overall health outcomes among patients with opioid use disorder.15 Consequently, ED settings offer important opportunities to identify patients with opioid use disorder and initiate treatment. Recent evidence suggests that ED-initiated buprenorphine increases subsequent engagement in addiction treatment and reduces illicit opioid use.27 Devoting more health resources to initiating evidence-based ED-based treatments for patients with opioid use disorder in health systems, including ED-initiated buprenorphine and referral to SUD treatment,27 may be a step toward improving health outcomes and reducing high SUD-related ED visits among patients with opioid use disorder.

Over time, all patients had fewer ED visits, and a greater decrease in ED use was observed for patients with SUDs compared with controls, although those with SUDs continued to have more ED visits. These ED utilization patters are consistent with general population studies, which show decreasing ED visits involving alcohol and opioid use disorders.4–6,8–11 At the same time, our ED utilization patterns regarding marijuana use disorder are inconsistent with national data, which suggest increasing ED visits involving marijuana-related problems.4,28 This national increase could be due to the combined effects of increasing marijuana potency, liberalizing views of the drug, and increasing trends toward its legalization.4,16 Notably, however, we found a decrease in ED use over time across patients with marijuana use disorder as well as those with alcohol and opioid use disorders, which may suggest that some patients’ health status improves (with the likely exception of more complex patients with co-occurring conditions) more quickly. Another possibility is that the observed decrease in ED use may be specific to those who receive care within integrate health systems in which specialty services are provided internally. For example, prior studies conducted within KPNC found that patients with SUD who had ongoing primary care and addiction treatment were less likely to have subsequent ED visits.29,30 It will be important for future studies in other systems to investigate the potential impact of specialty and primary care on reducing subsequent acute services across those with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders.

Our results confirm the work of prior studies showing that patients with alcohol and opioid use disorders, and to a lesser degree patients with marijuana use disorder, have frequent and increasing ED visits over time associated with poor health or complex medical conditions.9,13,14,24 Since our medical comorbidity measure combined acute and chronic conditions, it will be important for future work to identify which individual medical conditions (e.g., overdose, injury, respiratory infections, etc.) contribute most strongly to ED admission. Other characteristics that were not measured (e.g., income, education, etc.) may also influence ED use rates in patients with SUD, and understanding these factors may further help improve service planning efforts and ED-based treatments for this population. In addition, comorbid conditions were common among patients with SUD, and these individuals may have ED visits that require a range of medical treatments, psychiatric symptom stabilization, or detoxification from alcohol or drugs.

Limitations should be noted. Our use of provider-assigned diagnoses restricted the sample to patients with at least 1 of the 3 most common SUD diagnoses in 2010 (i.e., alcohol, marijuana, or opioid use disorder). As with other studies that have used claims-based data,8,30–35 our study captures patients with SUD through ICD-9 codes noted in health plan visits during the study period. This methodology is vulnerable to diagnostic underestimation.34 Therefore, the SUD prevalence data in our study may underestimate the general ED patient population prevalence. Although not available for this study, future database studies could examine if the inclusion of pharmacy-based prescription data to ICD-9 diagnosis improves prevalence estimates. Another potential limitation with the methods we used to select our SUD sample is that we required a single mention of an ICD-9 code for SUD during the study period to link the patient with that diagnosis. Although the single mention methodology is well established,31–35 it could result in an overestimation of the true diagnostic rates if diagnoses only mentioned one time in the EHR are more likely to be inaccurate. Patients were insured members of an integrated health system, and thus our results may not be generalizable to uninsured populations or other types of health systems. Our findings of SUD-related ED trends are somewhat inconsistent with prior work,9,10–13 which suggests a need for replication. All patients were required to have a health system visit in 2010 to enter the study, but they were not required to have a health system visit to remain in the study. These criteria may explain the steep decline in ED visits between 2010 and 2011 and subsequent leveling of ED use. We cannot identify the reason for why patients had an ED visit (i.e., opioid-related overdose, chronic disease type, etc.), which will be an important focus of future work. ED utilization that KPNC did not pay for is not captured, although we capture external, paid-for ED utilization through claims. Consequently, ED use may be higher than we report. Low base rates of SUDs other than alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders (e.g., cocaine use disorder, amphetamine use disorder, etc.) precluded our ability to examine the effect of these conditions on ED visits.

Conclusion

This study revealed consistent and remarkably high ED use in a sample of patients with alcohol, marijuana, and opioid use disorders, who had insurance coverage and access to integrated health services. ED use increased at greater rates for patients with medical comorbidities who also had an alcohol or opioid use disorder, and patients with opioid use disorder were at particular risk of high ED use. Results suggest that it will be important for future efforts to deliver enhanced ED-based screening and intervention efforts for persons with SUD. Such efforts should include a strong focus on reducing medical emergencies associated with opioid disorder, which may help improve health outcomes and reduce ED visits in this population.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Sidney R. Garfield Memorial Fund and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant T32DA007250. Funders were not involved in the study design; extraction, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

Appendix 1. Substance use disorder and psychiatric diagnoses and International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision codes

| ICD-9 code | Substance use disorder |

|---|---|

| 291 | Alcohol-induced mental disorders |

| 291.0 | Alcohol withdrawal delirium |

| 291.2 | Alcohol-induced persisting amnestic disorder |

| 291.3 | Alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations |

| 291.4 | Idiosyncratic alcohol intoxication |

| 291.5 | Alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with delusions |

| 291.8 | Other specified alcohol-induced mental disorders |

| 291.81 | Alcohol withdrawal |

| 291.82 | Alcohol-induced sleep disorders |

| 291.89 | Other alcohol-induced mental disorders |

| 291.9 | Unspecified alcohol-induced mental disorders |

| 292 | Drug-induced mental disorders |

| 292.0 | Drug withdrawal |

| 292.1 | Drug-induced psychotic disorders |

| 292.11 | Drug-induced psychotic disorder with delusions |

| 292.12 | Drug-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations |

| 292.2 | Pathological drug intoxication |

| 292.8 | Other specified drug-induced mental disorders |

| 292.81 | Drug-induced delirium |

| 292.82 | Drug-induced persisting dementia |

| 292.83 | Drug-induced persisting amnestic disorder |

| 292.84 | Drug-induced mood disorder |

| 292.85 | Drug-induced sleep disorders |

| 292.89 | Other specified drug-induced mental disorders |

| 292.9 | Unspecified drug-induced mental disorder |

| 303 | Alcohol dependence syndrome |

| 303.0 | Acute alcoholic intoxication |

| 303.00 | Acute intoxication in alcoholism, unspecified |

| 303.01 | Acute intoxication in alcoholism, continuous |

| 303.02 | Acute intoxication in alcoholism, episodic |

| 303.03 | Acute alcoholic intoxication in alcoholism, in remission |

| 303.9 | Other and unspecified alcohol dependence |

| 303.90 | Other and unspecified alcohol dependence, unspecified |

| 303.91 | Other and unspecified alcohol dependence, continuous |

| 303.92 | Other and unspecified alcohol dependence, episodic |

| 303.93 | Other and unspecified alcohol dependence, in remission |

| 304 | Drug dependence |

| 304.0 | Opioid-type dependence |

| 304.00 | Opioid-type dependence, unspecified |

| 304.01 | Opioid-type dependence, continuous |

| 304.02 | Opioid-type dependence, episodic |

| 304.03 | Opioid-type dependence, in remission |

| 304.1 | Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic dependence |

| 304.10 | Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic dependence, unspecified |

| 304.11 | Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic dependence, continuous |

| 304.12 | Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic dependence, episodic |

| 304.13 | Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic dependence, in remission |

| 304.2 | Cocaine dependence |

| 304.20 | Cocaine dependence, unspecified |

| 304.21 | Cocaine dependence, continuous |

| 304.22 | Cocaine dependence, episodic |

| 304.23 | Cocaine dependence, in remission |

| 304.3 | Cannabis dependence |

| 304.30 | Cannabis dependence, unspecified |

| 304.31 | Cannabis dependence, continuous |

| 304.32 | Cannabis dependence, episodic |

| 304.33 | Cannabis dependence, in remission |

| 304.4 | Amphetamine and other psychostimulant dependence |

| 304.40 | Amphetamine and other psychostimulant dependence, unspecified |

| 304.41 | Amphetamine and other psychostimulant dependence, continuous |

| 304.42 | Amphetamine and other psychostimulant dependence, episodic |

| 304.43 | Amphetamine and other psychostimulant dependence, in remission |

| 304.5 | Hallucinogen dependence |

| 304.50 | Hallucinogen dependence, unspecified |

| 304.51 | Hallucinogen dependence, continuous |

| 304.52 | Hallucinogen dependence, episodic |

| 304.53 | Hallucinogen dependence, in remission |

| 304.6 | Other specified drug dependence |

| 304.60 | Other specified drug dependence, unspecified |

| 304.61 | Other specified drug dependence, continuous |

| 304.62 | Other specified drug dependence, episodic |

| 304.63 | Other specified drug dependence, in remission |

| 304.7 | Combinations of opioid-type drug with any other drug dependence |

| 304.70 | Combinations of opioid-type drug with any other drug dependence, unspecified |

| 304.71 | Combinations of opioid-type drug with any other drug dependence, continuous |

| 304.72 | Combinations of opioid-type drug with any other drug dependence, episodic |

| 304.73 | Combinations of opioid-type drug with any other drug dependence, in remission |

| 304.8 | Combinations of drug dependence excluding opioid-type drug |

| 304.80 | Combinations of drug dependence excluding opioid-type drug, unspecified |

| 304.81 | Combinations of drug dependence excluding opioid-type drug, continuous |

| 304.82 | Combinations of drug dependence excluding opioid-type drug, episodic |

| 304.83 | Combinations of drug dependence excluding opioid-type drug, in remission |

| 304.9 | Unspecified drug dependence |

| 304.90 | Unspecified drug dependence, unspecified |

| 304.91 | Unspecified drug dependence, continuous |

| 304.92 | Unspecified drug dependence, episodic |

| 304.93 | Unspecified drug dependence, in remission |

| 305 | Nondependent abuse of drugs |

| 305.0 | Nondependent alcohol abuse |

| 305.00 | Alcohol abuse, unspecified |

| 305.01 | Alcohol abuse, continuous |

| 305.02 | Alcohol abuse, episodic |

| 305.03 | Alcohol abuse, in remission |

| 305.2 | Nondependent cannabis abuse |

| 305.20 | Cannabis abuse, unspecified |

| 305.21 | Cannabis abuse, continuous |

| 305.22 | Cannabis abuse, episodic |

| 305.23 | Cannabis abuse, in remission |

| 305.3 | Nondependent hallucinogen abuse |

| 305.30 | Hallucinogen abuse, unspecified |

| 305.31 | Hallucinogen abuse, continuous |

| 305.32 | Hallucinogen abuse, episodic |

| 305.33 | Hallucinogen abuse, in remission |

| 305.4 | Nondependent sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic abuse |

| 305.40 | Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic abuse, unspecified |

| 305.41 | Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic abuse, continuous |

| 305.42 | Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic abuse, episodic |

| 305.43 | Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic abuse, in remission |

| 305.5 | Nondependent opioid abuse |

| 305.50 | Opioid abuse, unspecified |

| 305.51 | Opioid abuse, continuous |

| 305.52 | Opioid abuse, episodic |

| 305.53 | Opioid abuse, in remission |

| 305.6 | Nondependent cocaine abuse |

| 305.60 | Cocaine abuse, unspecified |

| 305.61 | Cocaine abuse, continuous |

| 305.62 | Cocaine abuse, episodic |

| 305.63 | Cocaine abuse, in remission |

| 305.7 | Nondependent amphetamine or related acting sympathomimetic abuse |

| 305.71 | Amphetamine or related acting sympathomimetic abuse, unspecified |

| 305.72 | Amphetamine or related acting sympathomimetic abuse, continuous |

| 305.73 | Amphetamine or related acting sympathomimetic abuse, episodic |

| 305.8 | Nondependent antidepressant-type abuse |

| 305.80 | Antidepressant-type abuse, unspecified |

| 305.82 | Antidepressant-type abuse, continuous |

| 305.83 | Antidepressant-type abuse, episodic |

| 305.9 | Nondependent other mixed or unspecified drug abuse |

| 305.90 | Other, mixed, or unspecified drug abuse, unspecified |

| 305.91 | Other, mixed, or unspecified drug abuse, continuous |

| 305.92 | Other, mixed, or unspecified drug abuse, episodic |

| 305.93 | Other, mixed, or unspecified drug abuse, in remission Psychiatric condition |

| 300.00 | Anxiety disorder NOS |

| 300.01 | Panic disorder without agoraphobia |

| 300.02 | Generalized anxiety disorder |

| 300.2 | Phobia, unspecified |

| 300.21 | Panic disorder with agoraphobia |

| 300.22 | Agoraphobia without history of panic disorder |

| 300.23 | Social phobia (social anxiety) |

| 300.29 | Specific phobia |

| 300.3 | Obsessive compulsive disorder |

| 309.20 | Adjustment disorders with anxiety |

| 309.21 | Separation anxiety disorder |

| 309.24 | Adjustment disorder with anxiety |

| 309.81 | Posttraumatic stress disorder |

| 308.3 | Acute stress disorder |

| 314.00 | Attention deficit disorder, inattentive type |

| 314.01 | Attention deficit disorder, hyperactive/impulsive or combined type |

| 314.1 | Hyperkinesis with developmental delay |

| 314.2 | Hyperkinetic conduct disorder of childhood |

| 314.8 | Other specific manifests hyperkinetic syndrome, child |

| 314.9 | Attention deficit disorder NOS |

| 299.01 | Autistic disorder, residual state |

| 299.10 | Childhood disintegrative disorder |

| 299.11 | Childhood disintegrative disorder, residual state |

| 299.80 | Asperger’s disorder/pervasive developmental disorder |

| 299.00 | Autistic disorder, current or active state |

| 296.00 | Bipolar I disorder, single manic episode, unspecified |

| 296.01 | Bipolar I disorder, single manic episode, mild |

| 296.02 | Bipolar I disorder, single manic episode, moderate |

| 296.03 | Bipolar I disorder, single manic episode, severe without psychosis |

| 296.04 | Bipolar I disorder, single manic episode, severe with psychosis |

| 206.05 | Bipolar I disorder, single manic episode, in partial remission |

| 296.06 | Bipolar I disorder, single manic episode, in full remission |

| 296.1 | Manic recurrent episode |

| 296.10 | Manic disorder recurrent episode unspecified |

| 296.11 | Recurrent manic disorder, mild |

| 296.12 | Recurrent manic disorder, moderate |

| 296.13 | Recurrent manic disorder, severe |

| 296.14 | Manic affective disorder, recurrent episode, severe, specified as with psychotic behavior |

| 296.15 | Manic affective disorder, recurrent episode, in partial or unspecified remission |

| 296.16 | Recurrent manic disorder, full remission |

| 296.40 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode manic, unspecified |

| 296.41 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode manic, mild |

| 296.42 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode manic, moderate |

| 296.43 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode manic, severe without psychosis |

| 296.44 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode manic, severe with psychosis |

| 296.45 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode manic, in partial remission |

| 296.46 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode manic, in full remission |

| 296.50 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, unspecified |

| 296.51 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, mild |

| 296.52 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, moderate |

| 296.53 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, severe without psychosis |

| 296.54 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, severe with psychosis |

| 296.55 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed in partial remission |

| 296.56 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, in full remission |

| 296.60 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode mixed, unspecified |

| 296.61 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode mixed, mild |

| 296.62 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode mixed, moderate |

| 296.63 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode mixed, severe without psychosis |

| 296.64 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode mixed, severe in partial remission |

| 296.65 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode mixed, in partial remission |

| 296.66 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode mixed, in full remission |

| 296.7 | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode unspecified |

| 296.80 | Bipolar disorder NOS |

| 296.81 | Atypical manic disorder |

| 296.89 | Bipolar II disorder |

| 301.11 | Chronic hypomanic disorder |

| 301.13 | Cyclothymic disorder |

| 296.2 | Major depression, single episode, unspecified |

| 296.20 | Major depression, single episode, unspecified |

| 296.21 | Major depression, single episode, mild |

| 296.22 | Major depression, single episode, moderate |

| 296.23 | Major depression, single episode, severe without psychosis |

| 296.24 | Major depression, single episode, severe with psychosis |

| 296.25 | Major depression, single episode, in partial remission |

| 296.26 | Major depression, single episode, in partial remission |

| 296.3 | Major depression, recurrent, unspecified |

| 296.30 | Major depression, recurrent, unspecified |

| 296.31 | Major depression, recurrent, mild |

| 296.32 | Major depression, recurrent, moderate |

| 296.33 | Major depression, recurrent, severe without psychosis |

| 296.34 | Major depression, recurrent, severe with psychosis |

| 296.35 | Major depression, recurrent, in partial remission |

| 296.36 | Major depression, recurrent, in full remission |

| 296.82 | Atypical depressive disorder |

| 298.0 | Depressive-type psychosis |

| 300.4 | Dysthymia |

| 301.12 | Chronic depressive personality disorder |

| 311 | Depressive disorder NOS |

| 309.0 | Adjustment disorder with depressed mood |

| 309.1 | Prolonged depressive reaction |

| 309.28 | Adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood |

| 297.1 | Delusional disorder |

| 297.3 | Shared psychotic disorder |

| 298.8 | Brief psychotic disorder |

| 298.9 | Psychotic disorder NOS |

| 310.0 | Paranoid personality disorder |

| 301.1 | Affective personality disorder, unspecified |

| 301.11 | Chronic hypomanic personality disorder |

| 301.12 | Chronic depressive personality disorder |

| 301.13 | Cyclothymic disorder |

| 301.2 | Schizoid personality disorder |

| 301.20 | Schizoid personality disorder |

| 301.3 | Explosive |

| 301.4 | Obsessive compulsive personality disorder |

| 301.5 | Histrionic personality disorder |

| 301.50 | Histrionic personality disorder, unspecified |

| 301.51 | Chronic factitious illness with physical symptoms |

| 301.52 | Other histrionic personality disorder |

| 301.6 | Dependent personality disorder |

| 301.7 | Antisocial personality disorder |

| 301.8 | Other personality disorder |

| 301.81 | Narcissistic personality disorder |

| 301.82 | Avoidant personality disorder |

| 301.83 | Borderline personality disorder |

| 301.84 | Passive-aggressive personality |

| 301.89 | Other personality disorders |

| 301.9 | Unspecified personality disorder |

| 295.0 | Simple-type schizophrenia |

| 295.00 | Simple-type schizophrenia, unspecified |

| 295.01 | Simple-type schizophrenia, subchronic |

| 295.02 | Simple-type schizophrenia, chronic |

| 295.03 | Simple-type schizophrenia, subchronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.04 | Simple-type schizophrenia, chronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.05 | Simple-type schizophrenia, in remission |

| 295.1 | Disorganized-type schizophrenia, unspecified |

| 295.11 | Disorganized-type schizophrenia, subchronic |

| 295.12 | Disorganized-type schizophrenia, chronic |

| 295.13 | Disorganized-type schizophrenia, subchronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.14 | Disorganized-type schizophrenia, chronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.15 | Disorganized-type schizophrenia, in remission |

| 295.2* | Catatonic-type schizophrenia |

| 295.20 | Catatonic type schizophrenia, unspecified |

| 295.21 | Catatonic type schizophrenia, subchronic |

| 295.22 | Catatonic type schizophrenia, chronic |

| 295.23 | Catatonic-type schizophrenia, subchronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.24 | Catatonic-type schizophrenia, chronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.25 | Catatonic-type schizophrenia, in remission |

| 295.3 | Schizophrenia, paranoid type |

| 295.30 | Paranoid-type schizophrenia, unspecified |

| 295.32 | Paranoid-type schizophrenia, subchronic |

| 295.33 | Paranoid-type schizophrenia, chronic |

| 295.34 | Paranoid-type schizophrenia, subchronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.35 | Paranoid-type schizophrenia, in remission |

| 295.4 | Schizophreniform disorder |

| 295.40 | Schizophreniform disorder, unspecified |

| 295.41 | Schizophreniform disorder, subchronic |

| 295.42 | Schizophreniform disorder, chronic |

| 295.43 | Schizophreniform disorder, subchronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.44 | Schizophreniform disorder, chronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.45 | Schizophreniform disorder, in remission |

| 295.5 | Latent schizophrenia |

| 295.50 | Latent schizophrenia, unspecified |

| 295.51 | Latent schizophrenia, subchronic |

| 295.52 | Latent schizophrenia, chronic |

| 295.53 | Latent schizophrenia, subchronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.54 | Latent schizophrenia, in remission |

| 295.55 | Latent schizophrenia, in remission |

| 295.6* | Schizophrenia, residual type |

| 295.60 | Schizophrenic disorders, residual type, unspecified |

| 295.61 | Schizophrenic disorders, residual type, subchronic |

| 295.62 | Schizophrenic disorders, residual type, chronic |

| 295.63 | Schizophrenic disorders, residual type, subchronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.64 | Schizophrenic disorders, residual type, chronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.65 | Schizophrenic disorders, residual type, in remission |

| 295.7 | Schizoaffective disorder |

| 295.70 | Schizoaffective disorder, unspecified |

| 295.71 | Schizoaffective disorder, subchronic |

| 295.72 | Schizoaffective disorder, chronic |

| 295.73 | Schizoaffective disorder, subchronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.74 | Schizoaffective disorder, chronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.75 | Schizoaffective disorder, in remission |

| 295.8 | Other specified types of schizophrenia |

| 295.80 | Other specified types of schizophrenia, unspecified |

| 295.81 | Other specified types of schizophrenia, subchronic |

| 295.82 | Other specified types of schizophrenia, chronic |

| 295.83 | Other specified types of schizophrenia, subchronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.84 | Other specified types of schizophrenia, chronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.85 | Other unspecified types of schizophrenia, in remission |

| 295.9 | Unspecified schizophrenia |

| 295.90 | Unspecified schizophrenia, unspecified |

| 295.91 | Unspecified schizophrenia, subchronic |

| 295.92 | Unspecified schizophrenia, chronic |

| 295.93 | Unspecified schizophrenia, subchronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.94 | Unspecified schizophrenia, chronic with acute exacerbation |

| 295.95 | Unspecified schizophrenia in remission |

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Drs. Bahorik, Campbell, and Satre developed the research questions and study design. Ms. Kline-Simon extracted the data from the KPNC EHR, and Dr. Bahorik carried out the statistical analyses. Dr. Bahorik wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors provided critical revisions. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Cochran G, Woo B, Lo-Ciganic W, Gordon AJ, Donohue JM, Gellad W. Defining non-medical use of prescription opioids within health care claims: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2015;36:192–202. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.993491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cochran G, Bacci J, Ylioja T, et al. Prescription opioid use: patient characteristics and misuse in community pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2016;56(3):248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martineau F, Tyner E, Lorenc T, Petticrew T, Lock K. Population-level interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm: an overview of systematic reviews. Prev Med. 2013;57:278–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkow ND, Baler RD, Comptom WM, Weiss SRB. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New Engl J Med. 2014;370:2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volkow ND, Swanson JM, Evins EA, et al. Effects of cannabis use on human behavior, including cognition, motivation, and psychosis: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:292–297. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results From the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. NSDUH Series H-50. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927). http://www.samhsa.gov/data/ October 24, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kertesz SG. Turning the tide or riptide? The changing opioid epidemic. Subst Abus. 2017;38:3–8. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1261070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahorik AL, Satre DD, Kline-Simon AH, Weisner CM, Campbell CI. Alcohol, cannabis, and opioid use disorders, and disease burden in an integrated healthcare system. J Addict Med. 2017;11:3–9. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCabe CT, Woodruff SI, Zuniga MI. Sociodemographic and substance use correlates of tobacco use in a large, multi-ethnic sample of emergency department patients. Addict Behav. 2011;36:899–905. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu L, Swartz MS, Wu Z, Mannelli P, Yang C, Biazer D. Alcohol and drug use disorders among adults in emergency department settings in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherpitel CJ, Yu Y. Trends in alcohol- and drug-related emergency department and primary care visits: data from four U.S. national surveys (1995–2010) J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:454–458. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank JW, Binswanger IA, Calcaterra SL, Brenner LA. Non-medical use of prescription pain medication and increased emergency department utilization: results of a national survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;157:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockett LRH, Putnam SL, Jia H, Smith GS. Declared and undeclared substance use among emergency department patients: a population based study. Addiction. 2006;101:706–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanjuan PM, Rice SL, Witkiewitz K, et al. Alcohol, tobacco, and drug use among emergency department patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Cerda M, et al. US adult illicit cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and medical marijuana laws 1991–1992 to 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):579–588. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasin DS, Saha T, Bradley T, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1235–1242. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ray GT, Weisner CM, Mertens JR. Relationship between use of psychiatric services and five-year alcohol and drug use treatment outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:164–171. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson M, Charlson R, Peterson J, Marinopoulos S, Briggs W, Hollenberg J. The Charlson Comorbidity Index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:1234–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raudenbush DSW, Bryk DAS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing [computer software] Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016. Version 3.3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schukit M. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:493–501. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edlund M, Steffick D, Hudson T, Harris K, Sullivan M. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007;129:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374:1383–1391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calcaterra S, Glanz J, Binswanger I. National trends in pharmaceutical opioid related overdose deaths compared to other substance related overdose deaths: 1999–2009. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The NSDUH Report: Substance Use and Mental Health Estimates From the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Overview of Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. Sep 4, [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brady KT, McCauley JL, Back SE. Prescription opioid misuse, abuse, and treatment in the United States: an update. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;175:18–26. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15020262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onofrio GD, Chawarski MC, O’Connor PG, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine for opioid dependence with continuation in primary care: outcomes during and after intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):660–666. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-3993-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasin DS, Saba TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001–2002 and 2012 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1235–1242. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chi FW, Parthasarathy S, Mertens JR, Weisner CW. Continuing care and long-term substance use outcomes in managed care: early evidence for a primary care-based model. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:1194–1200. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.10.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parthasarathy S, Chi FW, Mertens JR, Weisner CW. The role of continuing care in 9-year cost trajectories of patients with intakes into an outpatient alcohol and drug treatment program. Med Care. 2012;50:540–546. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a66b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macy TA, Morasco BJ, Duckart JP, Dobscha SK. Patterns and correlates of prescription of opioid use in OEF/OIF veterans with chronic noncancer pain. Pain Med. 2011;12:1502–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rice JB, White AG, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, Brown DA, Roland CI. A model to identify patients at risk for prescription opioid abuse, dependence and misuse. Pain Med. 2012;13:1162–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan MY, et al. Trends in use of opioids for non-cancer pain conditions 2000–2005 in commercial and Medicaid insurance plans: the TROUP study. Pain. 2008;138:440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ray GT, Mertens JR, Weisner C. Family members of people with alcohol or drug dependence: health problems and medical cost compared to family members of people with diabetes and asthma. Addiction. 2009;104:203–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young JQ, Kine-Simon AH, Mordecai DJ, Weisner CM. Prevalence of behavioral health disorders and associated chronic disease burden in a commercially insured health system: findings of a case-control study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]