Abstract

METHODS

Most quantitative research on fertility decline in the United States ignores the potential impact of cultural and familial factors. We rely on new complete-count data from the 1880 U.S. census to construct couple-level measures of nativity/ethnicity, religiosity, and kin availability. We include these measures with a comprehensive set of demographic, economic, and contextual variables in Poisson regression models of net marital fertility to assess their relative importance. We construct models with and without area fixed effects to control for unobserved heterogeneity.

CONTRIBUTION

All else being equal, we find a strong impact of nativity on recent net marital fertility. Fertility differentials among second generation couples relative to the native-born white population of native parentage were in most cases less than half of the differential observed among first generation immigrants, suggesting greater assimilation to native-born American childbearing norms. Our measures of parental religiosity and familial propinquity indicated a more modest impact on marital fertility. Couples who chose biblical names for their children had approximately 3% more children than couples relying on secular names while the presence of a potential mother-in-law in a nearby households was associated with 2% more children. Overall, our results demonstrate the need for more inclusive models of fertility behavior that include cultural and familial covariates.

1. Introduction

Total fertility in the United States fell from 7.0 in 1835, one of the highest rates in the world, to 2.1 in 1935, one of the lowest (Coale and Zelnik 1963; Hacker 2003). Although most researchers emphasize the causal role of economic modernization (e.g. Jones and Tertilt 2008), cultural and familial factors affected the timing and pace of the decline. Fertility differentials were large between native-born and foreign-born women and among women residing in areas dominated by liberal, evangelical, and conservative churches, even after controlling for economic and demographic variables (Hareven and Vinvoskis 1975; Morgan, Watkins and Ewbank 1994, Haines and Hacker 2011). Parents relying on biblical names for the children had more children than parents relying on secular names, suggesting an association between parental religiosity and marital fertility (Hacker 1999; 2016). There is also evidence of a significant intergenerational link between parents’ and children’s fertility during the decline, with men and women from large families of origin tending to have more children than men and women from small families (Jennings et. al 2012). Couples living in New England had persistently lower fertility throughout the decline, and the region continues to exhibit unique demographic behaviors today, more in line with the “low-low” fertility rates in parts of Europe than with the rest of the United States (Lesthaghae and Neidert 2006; Hacker 2016). These differentials suggest the need for a better understanding of the contribution of cultural and familial influences in the U.S. fertility transition.

This paper leverages the analytical power of the complete-count 1880 census microdata database of the United States, part of the North Atlantic Population Project (Minnesota Population Center 2015), to examine the roles of culture and family in the early phase of the fertility transition. The dataset includes over 50 million individuals. Although there are some limitations to these data for the study of fertility – e.g., only living children were enumerated by the census and the cross-sectional design limits our ability to evaluate selection effects – the advantages of such a large dataset are enormous. One advantage is our ability to create contextual variables from outside the immediate household. We are able to construct, for example, a measure of kin propinquity from surnames in nearby households to test hypotheses related to the role of nearby kin in fertility decisions (Mace and Sear 2005; Sear et al. 2003). We also examine the role of kin availability within the household, parental religiosity, nativity, and traditional economic correlates on fertility differentials in 1880. Our analysis—while reaffirming the importance of economic factors typically stressed by other researchers—confirms the importance of cultural and familial factors in the early stages of the fertility decline and demonstrates the need for more inclusive models of couples’ reproductive behavior.

2. Prior research on the U.S. fertility transition

Quantitative research on the U.S. fertility transition has emphasized economic factors. Because U.S. fertility decline began when the nation was still overwhelmingly rural, researchers have focused their investigations on the possible role of changes in the agricultural economy on reproductive behavior. Differentials in child-woman ratios, which are available at the county level between 1800 and 1860, have been associated with differentials in the availability of land for farming, the price of local farms, and other measures of the agricultural economy, suggesting that parents adapted to declining agricultural opportunities by limiting their fertility (Yasuba 1962; Forster and Tucker 1972; Easterlin 1976; Vinovskis 1976; Easterlin, Alter, and Condran 1978; Smith 1987; Carter, Ransom and Sutch 2004; Haines and Hacker 2011). Research on the post 1860 period has also emphasized couples’ economic motivations to reduce fertility, but has stressed the contributing roles of urbanization, industrialization, higher incomes, and compulsory schooling (Guest 1981; Guest and Tolnay 1983; Wanamaker 2012). In their recent analysis of children ever born data in the 1900, 1910 and 1940–1990 IPUMS samples, Jones and Tertilt (2008) found a consistent negative relationship between fertility and “occupational income” from the earliest observable birth cohort in 1826. Other researchers have highlighted large and increasing fertility differentials between women married to men in farm and non-farm occupations, especially between women married to farmers and women married to men in professional, sales, and managerial occupations (Stevenson 1920; Haines 1992; Dribe, Hacker and Scalone 2014).

Qualitative studies have stressed the importance of familial, cultural and religious change in the fertility transition. Rapid social change in the nineteenth century led to greater acceptance of the idea of smaller families, especially among native-born couples, who demonstrated greater willingness to adopt birth control methods than foreign born couples (Smith 1974; Degler 1980; Klepp 2009; Vinovskis 1976; King and Ruggles 1990; Smith 1994; MacNamara 2014). New contraceptive methods and advice manuals were initially promoted by religious “free-thinkers” such as Robert Dale Owen and Charles Knowlton, while opponents warned of “conjugal onanism,” suggesting that secularization may have been a necessary pre-condition to the practice of birth control (Brodie 1994: 59; Smith 1994). Although only a few quantitative studies have attempted to assess the importance of religion in the early stages of the U.S. fertility transition, there is evidence that traditional religious beliefs, as proxied by the presence of more conservative/liturgical churches and parental reliance on biblical names for children, was an impediment to marital fertility control, while a more secular outlook, as proxied by the presence of more liberal/pietistic churches and parental reliance on secular names for children, was associated with the conscious practice of family limitation techniques (Parkerson and Parkerson 1988; Leasure 1982; Smith 1987; Hacker 1999; Haines and Hacker 2011).

American historical demographers have paid little attention to the role of kin in fertility decisions. A recent study based on the Utah Historical Database, however, found higher fertility among women with living mothers and mothers-in-law during the fertility transition (Jennings et al. 2012). The finding is consistent with research in evolutionary anthropology that stresses the importance of economic and physical assistance from relatives, particularly post-menopausal grandmothers, in the rearing of human children. When fecund couples reside far from their own parents, the labor and economic burden of child rearing falls more on the child-bearing couple. Couples without significant help are more likely to reduce family size, while those surrounded by kin networks will be inclined to have more children (Hrdy 2009; Hawkes, O’Connell, and Blurton Jones 1989; Turke 1988; Sear and Coall 2011). Proximity to kin may also induce higher levels of fertility through an effect called “kin priming” (Mathews and Sear, 2013; Newson, Postmes, Lea, and Webley, 2005). People living close to kin have higher fertility because social interactions with their kin influence them—at least subconsciously—to have more children. Loosely speaking, kin priming is the effect of your parents asking you when you are going to have another baby. While these two effects are theoretically distinct, they operate in mostly the same direction, with increasing proximity leading to higher fertility. Sears and Coall’s useful survey of 39 studies (2011) indicates that paternal kin have a more consistent pronatal impact on fertility than maternal kin, consistent with the evidence that maternal kin may act at times to protect women from maternal depletion—the negative impact on a woman’s own health of having additional children.

3. Measurement of kin proximity

The measurement of kin proximity is a core challenge of this literature. We observe that declining fertility in nineteenth-century Europe and North America was coincident with high levels of domestic and international migration, and that migration was more often across greater distances in the nineteenth century than it had been in the eighteenth century. But this level of aggregation is too coarse to establish links between kin proximity and fertility decisions. What matters for individual fertility decisions is not overall migration rates, but the migration, or not, of your relatives.

Thus we need some measure of the proximity of relatives to women of child-bearing age. While household surveys and censuses typically define the relationships between people within the same household, they do not enumerate the relationship of people to those residing outside the household (Ruggles and Brower 2003). More generally, this is a problem of measuring social networks and relationships. Censuses can tell us when people reside together, and often describe their relationship to each other. Institutional records such as school rolls or church membership lists can be used to place people in the same social milieu. But these are fairly selective sources, and only capture relationships within formal organizations. Measuring social networks of any kind often requires direct questions to subjects about who they are related to in particular ways, including kin.

Thus, kin proximity has to be measured by direct questions on the distance to defined categories of family members such as parents and siblings. Ernest Burgess’ pioneering and influential surveys of marriage in the 1930s may have been the first to include questions of this nature. The questionnaires for Burgess’ first study—the 526 study in the early 1930s—asked explicitly how far couples lived from the parents of the wife and the husband (Burgess and Cottrell 1939). While the question was repeated in his larger (“Over 1000”) longitudinal survey of engaged and married couples beginning in the late 1930s, little use of the variable was made in the main publications resulting from these studies (Burgess and Wallin, 1953). Geographical proximity to parents and in-laws was regarded as an “intruding” variable in the more important analysis of measures of emotional closeness (Wallin 1954). Subsequent studies by other sociologists and demographers in the 1950s also collected measures of physical proximity, but made perfunctory use of it (Landis 1960; Wallin 1954). A precedent for collecting measures of kin proximity had been established, and major surveys of family relationships in several countries now include questions on geographic proximity of kin (Sear and Coall 2011). For example in the United States, surveys such as the Health and Retirement Survey include questions on kin proximity. Research with these data has found that kin proximity is an important influence on adults’ residential moves. Kin who live close by are a brake on moving, and many moves are motivated by the imperative of reducing distance between adult children and parents (Spring, Ackert, Crowder and South 2017). Yet, much of this data pertains to families in the recent past after the peak of the Baby Boom or to families in modern lower income societies. We know little about the effects of kin proximity in North America and Western Europe during the early stages of the demographic transition.

The question of measurement is again central. Without directly enumerated questions on the topic, how can we measure kin proximity for representative populations? Genealogical databases are a potential source that allow relationships between people living in different households to be mapped (Smith et al. 2005). A strength of genealogical databases is that they have high accuracy in identifying beyond-household kinship relations in historical settings. Yet an obvious weakness is that they can only be constructed for unusual populations with excellent civil registration systems or where descendants can identify the relationships. In addition, they often lack detailed socioeconomic and residential data. The Utah Historical Database, constructed from genealogical information captured for ancestors of the Church of Latter Day Saints, for example, which was used by Jennings, Sullivan and Hacker to examine the potential impact of mothers’ and mothers’-in-law on women’s fertility decisions (2012), lacks detailed residence information. The positive impact of mothers’ and mothers’-in-laws on fertility was estimated from their vital status (living or dead), not their physical proximity to their children. In late nineteenth century Montréal, Sherry Olson traced families forward from the 1881 to 1901 census, and with familial relationships taken from 1881 was able to see how closely parents and adult children resided in 1901. Adult children lived close to their parents, with three quarters living within 2km if they were within Montréal, suggesting that family ties were important in deciding where to live (Olson 2015).

In this paper we take advantage of the recent availability of complete-count census data to measure the proximity of potential kin to married couples and study its effects on fertility. Complete-count census data with identifying information (surnames) have become publicly available to scholars in the past decade (Ruggles 2014). Scholars have used these data to study related topics such as household composition (Ruggles 2009) and fertility (Dribe, Hacker, and Scalone 2014), taking advantage of the detailed information on within-household relationships in these datasets.1

We can infer the presence of potential kin in nearby households using surnames, parental birthplaces, and ages, and by taking advantage of the way in which the census was taken. In the United States, at least, the census collected information from households in essentially sequential order (Grigoryeva and Ruef 2015; Logan and Parman 2017). This sequence is maintained in the data through a variable serial that identifies unique households within a census year (within households individuals are further identified by an index called pernum). Serial numbers respect the sequence of the original enumeration that was constructed by i) enumerating households in geographic sequence, and ii) numbering enumeration sheets in a manner that maintained this geographic order. However, not all sequential serial numbers are adjacent. Serial maintains its sequence from state to state, and it is highly unlikely—though not absolutely impossible—that serialt is a real neighbor of serialt+1 when t and t+1 are in different states, as relatively few state borders are found in settled areas, particularly in the nineteenth century. Thus, we must look for smaller geographic units in which to sort our serial numbers and find adjacent houses.

Enumeration districts formed the basic administrative geography of the census, within which households were canvassed sequentially. In the 1880 census from which we draw the data for this paper there were 11,349 enumeration districts for a population of just over 50 million. Enumeration districts ranged in size from a population of 10 to 30,000. The largest enumeration districts were found in large, dense cities such as Chicago, New York, St Louis and Cleveland, where they were geographically small and contiguous. Although the local administration of the census in the United States was problematic because it led to greater variability in enumeration practices, it did allow local officials to construct enumeration districts that conformed to areas recognized by the people they were enumerating. Where the borders are known, they run down major roads, or along barriers such as geographic features or railroads. In rural areas enumeration districts also conformed to recognized neighborhoods (Logan and Parman 2017). For the vast majority of households within an enumeration district, households with sequential serial numbers in the data are, in fact, adjacent in physical space, and if not adjacent very close.

We take advantage of this property of the complete count data and individuals’ reported surnames, birthplaces, and ages to measure couples’ potential kin in nearby houses. In our initial analysis, we followed the existing literature using neighbors in complete count census data and analyzed only the two adjacent households, focusing on identifying the presence of a potential mother-in-law for all currently-married women of childbearing age (Grigoryeva and Ruef 2015; Logan and Parman 2017). We extend prior scholarship by examining a wider window around the focal household to identify additional potential mothers-in-law, although the likelihood of finding one declined with each household. Ultimately, as discussed in more detail below, we limited our search to ten “nearby” households, defined as the five households on either side of each focal woman.

A limitation of using neighbors within the same enumeration district is that people may be potentially proximate to kin living in the same town or city, but not within the same enumeration district. Because enumeration district boundaries have not been published for all areas of the United States in 1880 we are unable to identify bordering districts. It is also possible that potential in-laws in the same enumeration district in a densely-settled town or city were physically close physically close but not within our search window of ten nearby households. If an enumerator visited dwellings on one side of a city block before returning on the opposite side, for example, it is possible that a mother-in-law living in a dwelling directly across the street from the focal woman’s dwelling or in a dwelling immediately behind on the next block—these can be understood as neighbors over the back fence—would not be identified as nearby kin. Street addresses could potentially be used to identify households in close proximity to each other. However, in rural areas, most houses lacked street addresses and even in urban areas they were not consistently collected. Thus, we rely on the geography of enumeration districts to define our boundaries on proximity, noting that later censuses that do include street addresses yield considerable promise for identifying potential kin on, for example, the same block of a street. To some extent, our inclusion of urban/rural residence and size of city variables in our empirical models controls for the potential density of kin networks in towns and cities. With these strengths of our measure of geographic proximity —“nearby” households in the data are geographically close—and limitations—borders of districts are not known and we may miss some potential kin living nearby—we turn to discussion of measuring actual kin within the household, and potential mothers-in-law outside it.

Within the household the census began directly enumerating relationship for the first time in the 1880 census. The version of the 1880 census that we use in this article comes from the North Atlantic Population Project, for which the original records were transcribed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS). In the process of transcribing the complete 1880 census the LDS removed information on non-family relationships within the household (Minnesota Population Center 2015; Roberts, et al. 2003). Thus, all people with non-familial relationships such as boarders and lodgers receive the same relationship code in the data. However, our analysis focuses on currently-married women aged 20-49 living with their spouse (henceforth, the “study population”), 99% of whom had a familial relationship to the head of household. Thus, we can reliably determine within-household kin for nearly the entire study population. After restricting the universe to women with non-missing information, our study population includes 5,379,539 women.

To measure kin and other sources of support for child rearing within the household we construct indicators for having a co-resident mother–in-law (3.3% of women in the study population) or a co-resident mother (2.9%). We also measure the number of other females 11 years or older, both kin and non-kin living in the household. Almost half (45.3%) of currently-married 20-49 year old women had a co-resident females in the household, and 38.6% of women had a co-resident female family member 11 or older (who was not their mother or mother in law). Women with a co-resident mother or mother-in-law were more likely to have other female relatives living with them. These measures of household composition are standard in the fertility literature using household censuses.

Our measure of potential mothers-in-law outside the household is more novel. We know from the census enumeration the age and last name of the husband of currently married women residing with their husbands. To identify potential mothers-in-law we first looked in the households immediately above and immediately below to see if there is an ever-married woman sharing the husband’s last name and husband’s mother’s birthplace, and more than 15 years older than the husband. We set the minimum age gap between a husband and a potential mother-in-law at 15 for physiological reasons—few children are born to women aged under 15, noting that the same minimum age for mothers is used by IPUMS when imputing relationships. Slightly over 2% of women in our study population had a potential mother-in-law in the two nearest households. Increasing our search window by a factor of five to the nearest 10 households (+/- 5 households from the focal household), increased the number of potential mothers-in-law by a factor of three, to 6.9%. Given the much greater programming challenges of larger search windows and the increasing possibility of false positives, we decided to limit our window to the nearest 10 households.

Although we label our variable “potential mothers-in-law,” it is likely that some of the identified “mothers-in-law” are aunts-in-law, significantly older sisters-in-law, and other ever-married female in-laws. It was therefore possible for focal women to have more than one potential mother-in-law. Among the approximately 479,000 women with a potential mother-in-law in nearby houses, however, 437,000 had just one potential mother-in-law. Although a higher number of potential mothers-in-law had meaning, we decided to treat the measure as a dichotomous indicator. The variable was set to zero for focal women with a co-resident mother-in-law and one for women with one or more potential mothers-in law. We excluded from our construction of neighboring houses any group quarters, such as prisons or hospitals or poor farms and limited our search to the nearest ten regular households.

An outline of how we proceed programmatically may be helpful. Previous work using the complete count census to identify the characteristics of neighbors has focused on racial composition of households in an era in which households themselves were nearly universally racially homogeneous (Grigoryeva and Ruef 2015; Logan and Parman 2017). When households are homogeneous on some social dimension—such as race—their characteristics can be summarized easily by collapsing the dataset to a single observation per household. Looking forward or back one household to find the characteristics of neighbors is then a matter of searching forward or back one observation and comparing the characteristic.

In general this is not possible in our situation for several reasons. First, in some households there may be multiple women whose potential kin we are interested in finding. Indeed, 16% of women in our study population resided in a household with 2 or more women age 20-49. Even when these women come from the same family their potential mothers (in law) are not necessarily the same people. This will be the case in living situations such as a woman residing with her own mother, or two married couples sharing a household (e.g., married brothers farming together).

Secondly, the women whose fertility we are interested in may not have been from the same family groups. Nearly a quarter (23%) of non-group-quarter households in the United States census of 1880 had 2 or more family groups present. To fix ideas about what this means, a household with one family and an unrelated family lodging with them has multiple family groups. The potential kin for these women in neighboring households may be different people as their threshold ages and matching last names and birthplaces will differ. The problem of multiple family groups is less frequent than the prior question of multiple fertile women in a household: 97% of women in the study population belonged to the first family group in the household.

Finally, households are of different size and the women whose fertility we are interested in measuring will necessarily appear at variable places in the household. Similarly, the potential mothers or mother-in-law will appear at different points in the neighboring households. For all the reasons just adduced we cannot summarize the potential kin we are interested in measuring at a household level, and we cannot pre-specify the number of adjacent individual observations in the data to search for potential kin.

Our programming solution to this issue is to create duplicate copies of neighboring households, re-number the serial numbers for these newly duplicated observations to bring them inside the household with re-coded relationships to the “focal” household. Table 1 illustrates this using the example of the household of Mary Baker, who lived in the township of Brewster, Massachusetts in 1880. (For illustration, we limit this example to the two households immediately adjacent to Baker’s. Our full program, however, searches for Baker’s potential kin in the five households prior to her household and five households after her household). As shown in the table, Mary Baker’s household appears first as the neighbor immediately below the Ellis household. Mary and her adult children appear with the relationship of neighbor in this household with the modified serial number 1. Next we move to a household and its neighbors where Mary and her family is the focal household with actual and modified serial number 2. The Ellis household re-appears, but this time the household’s modified serial number is changed to 2 and relationships are all modified to be Neighbor (of the Mary Baker household). Another household appears in modified serial number 2, the Henry Baker household, who are below Mary’s household, and also take on the relationship to Mary’s household of neighbor. When we focus on Mary’s household there are 4 women whose fertility we could be interested in measuring, Mary’s four teenage and adult daughters. It turns out they are all single, however. Finally, Mary’s household re-appears this time as the neighbor above the Henry Baker household (modified serial number 3). Focusing on the Henry Baker household, we see a married woman (Almira) with 2 children, and when we look to above we find Mary who meets all the characteristics to be Almira’s mother-in-law (Henry’s mother). She is more than 15 years older and shares Almira’s surname.

Table 1.

Example of Data Processing

| Actual serial | Modified serial | pernum | Relationship to household head | Neighbor index | Last Name | First Name | Age | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | Head | 0 | ELLIS | THADDEUS | 48 | Male |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | Spouse | 0 | ELLIS | CAROLINE | 46 | Female |

| 1 | 1 | 3 | Child | 0 | ELLIS | THADDEUS F. | 23 | Male |

| 1 | 1 | 4 | Child | 0 | ELLIS | EDWIN P. | 22 | Male |

| 1 | 1 | 5 | Child | 0 | ELLIS | WILLIAM W. | 19 | Male |

| 1 | 1 | 6 | Child | 0 | ELLIS | JULIA A. | 17 | Female |

| 1 | 1 | 7 | Child | 0 | ELLIS | GILBERT E. | 14 | Male |

| 1 | 1 | 8 | Child | 0 | ELLIS | ANGIE B. | 9 | Female |

|

| ||||||||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | Neighbor | 1 | BAKER | MARY C. | 54 | Female |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | Neighbor | 1 | BAKER | LAURA E. | 29 | Female |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | Neighbor | 1 | BAKER | FANNIE C. | 22 | Female |

| 2 | 1 | 4 | Neighbor | 1 | BAKER | ELEANOR J. | 20 | Female |

| 2 | 1 | 5 | Neighbor | 1 | BAKER | LYDIA J. | 17 | Female |

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | Neighbor | −1 | ELLIS | THADDEUS | 48 | Male |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | Neighbor | −1 | ELLIS | CAROLINE | 46 | Female |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Neighbor | −1 | ELLIS | THADDEUS F. | 23 | Male |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | Neighbor | −1 | ELLIS | EDWIN P. | 22 | Male |

| 1 | 2 | 5 | Neighbor | −1 | ELLIS | WILLIAM W. | 19 | Male |

| 1 | 2 | 6 | Neighbor | −1 | ELLIS | JULIA A. | 17 | Female |

| 1 | 2 | 7 | Neighbor | −1 | ELLIS | GILBERT E. | 14 | Male |

| 1 | 2 | 8 | Neighbor | −1 | ELLIS | ANGIE B. | 9 | Female |

|

| ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 1 | Head | 0 | BAKER | MARY C. | 54 | Female |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | Child | 0 | BAKER | LAURA E. | 29 | Female |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | Child | 0 | BAKER | FANNIE C. | 22 | Female |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | Child | 0 | BAKER | ELEANOR J. | 20 | Female |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | Child | 0 | BAKER | LYDIA J. | 17 | Female |

|

| ||||||||

| 3 | 2 | 1 | Neighbor | 1 | BAKER | HENRY E. | 30 | Male |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | Neighbor | 1 | BAKER | ALMIRA C. | 28 | Female |

| 3 | 2 | 3 | Neighbor | 1 | BAKER | LYDIA A. | 7 | Female |

| 3 | 2 | 4 | Neighbor | 1 | BAKER | — | 2 | Female |

|

| ||||||||

| 2 | 3 | 1 | Neighbor | −1 | BAKER | MARY C. | 54 | Female |

| 2 | 3 | 2 | Neighbor | −1 | BAKER | LAURA E. | 29 | Female |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | Neighbor | −1 | BAKER | FANNIE C. | 22 | Female |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | Neighbor | −1 | BAKER | ELEANOR J. | 20 | Female |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | Neighbor | −1 | BAKER | LYDIA J. | 17 | Female |

|

| ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | 1 | Head | 0 | BAKER | HENRY E. | 30 | Male |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | Spouse | 0 | BAKER | ALMIRA C. | 28 | Female |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | Child | 0 | BAKER | LYDIA A. | 7 | Female |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | Child | 0 | BAKER | — | 2 | Female |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | Neighbor | 1 | ROGERS | DEMIRA | 39 | Male |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | Neighbor | 1 | ROGERS | MELISSA J. | 38 | Female |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | Neighbor | 1 | ROGERS | FRED L. | 14 | Male |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | Neighbor | 1 | ROGERS | FLORENCE E. | 4 | Female |

| 4 | 3 | 5 | Neighbor | 1 | ROGERS | CLARENCE I. | 4 | Male |

Nearly every household in the data is treated in the same way as this example, with the search window expanded to plus or minus five households. Households appear once as the focal household (neighbor index = 0), five times as the neighbor before (or above) the focal household in the database (neighbor index = −1 to −5) and five times as the neighbor after (or below) the focal household (neighbor index = 1 to 5). We modify this procedure for households within five households of the beginning or end of the enumeration district. In these cases we search for kin among the ten closest households, which are the ten households below the first household in the enumeration district, one household before and nine households after the second household, etc. to the ten households above the last household in the district. We implement this strategy in Stata. Stata holds the data in memory, which allows us to easily compute measures of potential kin within the group identified by the modified serial number (the focal household augmented by its neighbors). As noted above there can be multiple women within a household for whom we are interested in finding potential kin, and the criteria for those kin may differ. Within a household the number of women we are interested in finding kin for is small, so we run a loop for each target woman, marking neighbors in the augmented household as potential kin or not. Finally, for each target woman we sum the number of potential kin of each category.

4. Measurement of nativity and religiosity

Fertility differentials by nativity were first highlighted by nineteenth-century observers. In 1877, for example, Dr. Nathan Allen estimated that the birth rate among the foreign born in New England was twice that of the native born, a result, he believed, of a desire for a higher standard of living among the native born and, perhaps, physiological degeneration among native-born men and women related to changes in work and education (Allen 1877).

Modern studies of the mid nineteenth-century fertility have confirmed that the native-born population of New England was on the vanguard of the fertility transition (Main 2006, Hacker 1999). The foreign born population lagged well behind, suggesting the persistence of customs and values opposed to the practice of birth control (Vinovskis 1982; Atack and Bateman 1987; Forster and Tucker 1972; Hareven and Vinovskis 1975). Other factors may have played a role, however, including native and foreign-born differentials in SES, insecurities associated with minority group status, and immigrant selection factors (Goldscheider and Uhlenberg 1969; Kahn 1988, 1994; Forste and Tienda 1996). Continued marital fertility decline among native-born couples, persisting high fertility rates among “old” immigrant groups, and the arrival of new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe with strong family systems and high fertility regimes widened fertility differentials in the early twentieth century (King and Ruggles 1990; Morgan, Watkins and Ewbank 1992; Gjerde and McCants 1995; Reher 1998; MacNamara 2014).

Although the acquisition of English and occupational and social mobility by foreign-born couples was associated with lower marital fertility rates, nativity remained a significant correlate of marital fertility rates. Morgan, Watkins and Ewbank (1994) found substantial marital fertility differentials by nativity in 1910 even after the controlling for age, occupation, residence, duration in the United States, and ability to speak English. Second generation couples (native born of foreign-born parents) typically achieved fertility levels between that of native-born whites and first generation immigrants, suggesting a slow process of acculturation to American norms spanning several generations.

Prior research has also confirmed the existence of substantial differentials in fertility by nativity in the nineteenth century. Most studies, however, are based on aggregate child-woman ratios, include few other explanatory variables, and do not estimate the impact of generation on fertility. Our analysis models marital fertility at the level of individual couples, includes a diverse set of economic and cultural covariates, and estimates first and second generation fertility relative to that of native born couples of native parentage. Because the nativity of wives and husbands were highly correlated, we treat nativity as a couple-level measure.2 If only one partner was native born, the nativity of the foreign-born partner was used. If both partners were foreign born but with different nativities, we relied on the wife’s nativity. We consider fifteen different nativities (first generation Irish, German, British, Canadian, Scandinavian, French, and Other foreign born; second generation Irish, German, British, Canadian, Scandinavian, French and Other foreign-born parents; and native born of native parents). Second generation couples were defined a couples having one or more parents who were foreign born. When husbands and wives had parents with different nativities, we identified the couples’ second generation nativity as the mother’s nativity over the father’s nativity, and the nativity of the wife’s mother and father over the husband’s mother and father. All else being equal, it was expected that foreign-born couples originating from countries that had yet to experience the onset of the fertility transition (all countries except France) would be less willing than native born couples to limit their fertility.

Nativity is highly correlated with the availability of potential kin. First-generation couples likely had few parents in the United States. Cultural norms about living with parents may have varied among groups, including among second-generation immigrants. Our data indicate that native-born couples of native parentage (NBNP) were 3.7 times more likely to have a potential mother-in-law residing within ten households than all foreign-born couples combined, 65% more likely to have a co-resident mother-in-law, and 19% more likely to have a co-resident mother. Differences between NBNP couples and second-generation couples were more modest, but still significant. NBNP couples had about 37% more potential mothers-in-law nearby, 7% more co-resident mothers-in-law, and 10% fewer co-resident mothers than second-generation couples combined. To account for these differences, we interacted all nativity and kin availability variables in our models.

Our measurement of parental religiosity was less direct. Unfortunately, systematic information on religious affiliation, church attendance, and religiosity is not available until the mid-twentieth century. To overcome data limitations–which also afflict most other countries experiencing fertility declines in the nineteenth century—the editors of a recent book on religiosity and fertility decline urged investigators to “be innovative in their research, and where possible to use indirect indicators for the relevant [religious] dimensions” (van Poppel and Derosas 2006: 10-11). In the nineteenth-century United States, where parents were free to name their children without church or state restrictions, one such indirect indictor of religiosity is parents’ choice of biblical or non-biblical names for their children (Hacker 1999; 2016). Large shifts in the name pool over the course of the nineteenth century indicate that parents took advantage of this freedom. Between 1780 and 1880, the percentage of white males given a name found in the Bible fell from 67 to under 30 percent. Nineteenth-century observers bemoaned the trend, associating it with religious declension. In a book on manners published in 1873, for example, Robert Tomes observed that while the pious continued to “turn to the Bible for a choice, and affix to their children, with an almost superstitious hope of sanctification, the names of some patriarch, saint, or apostle,” the non-pious were more apt to borrow “the name of a favorite hero or heroine” from a novel or a name associated with patriotic causes, such as Washington and Franklin (cited in Hacker 1999).

All else being equal, we assumed that parents choosing a higher proportion of biblical names for their children either: (a) held more deeply felt religious beliefs than parents choosing a higher proportion of secular names, or (b), were less open to sources outside of religion for authoritative positions on various topics, including contraception and abortion (Chaves 1994; Yamane 1997; Moore 1989) than parents choosing a higher proportion of secular names. Some measurement error is inevitable, of course. To the extent that the measure imperfectly captures parental religiosity, coefficients will be biased downward. In all regression models couples’ nativity was interacted with the proportion of children given biblical names to control for the possibility of couples emigrating from countries with significant naming restrictions. The child naming variable was centered to allow interpretation of the main effect at the model mean. We also constructed models with the universe limited to the native-born population of native parentage to limit the possible bias of including immigrant groups with different naming practices.

5. Methods and results

We rely on Poisson regression of the number of own children less than age five as the dependent variable. Because we lack information of children who may have died in the five years prior to the census, the variable is more precisely a measure of net marital fertility or marital reproduction.3 Four models are constructed. Model 1 is a Poisson regression of all currently married women age 20-49 with spouses present. After restricting the universe to women with non-missing information, our study population includes 5,379,539 women. Model 2 employs the same universe and variables, but applies fixed effects at the State Economic Area level (an aggregation of two or more contiguous counties identified by the 1950 census as sharing similar economic characteristics). In 1880 there are 423 SEAs containing an average of about 12,800 child-bearing women. The fixed effects controls for unobserved heterogeneity across SEAs. Models 3 and 4 are based on the same specifications of models 1 and 2 but with the universe limited to native-born couples with native-born parents, which reduces the study population to 3,092,056 women. We focus our discussion on model 2.

Independent variables were sorted into five major groups: variables associated with availability of potential help rearing children (co-residence of mother, co-residence of mother-in-law, number of co-residing older females, and the presence of a potential mother-in-law living in ten nearby households), variables primarily associated with economic “readiness,” variables primarily associated with cultural “willingness,” other covariates, and demographic control variables. Readiness variables included women’s labor force participation, spouse’s occupation, the average value of farms in couples’ county of residence, and the proportion of children age 8-14 in the county in school. Couples living on farms, for example, where children could assist in farm chores and were less an economic burden, might not perceive an economic benefit from lowering their fertility and were therefore less “ready” to adopt birth control methods. Cultural “willingness” variables included proportion of children biblically named, race, and couples’ nativity and generation. Other covariates and demographic control variables included population size of town or city, women’s age, age differential from spouse, and prior fertility, defined as the number of living children in the household age 5 and above. The latter variable serves as a control for the focal woman’s fecundity.

A few of our independent variables were modestly correlated. The presence of a focal woman’s mother in the household, for example, was negatively correlated with the presence of a mother-in-law (r = −0.02) and positively correlated with the number of other females over age 10 in the household (r = 0.03). Unsurprisingly, the number of females age 11 and older in the household available for childrearing assistance was strongly correlated with a woman’s prior fertility (r = 0.54). Although regression coefficients are unbiased by multicollinearity, standard errors are inflated, which can cause coefficients to be estimated less accurately when the number of cases is small. However, because we have complete population data there is no sampling error, and so standard errors will not be affected by multicollinearity (Goldberger 1991: 245-251).

5. 1 Descriptive Results

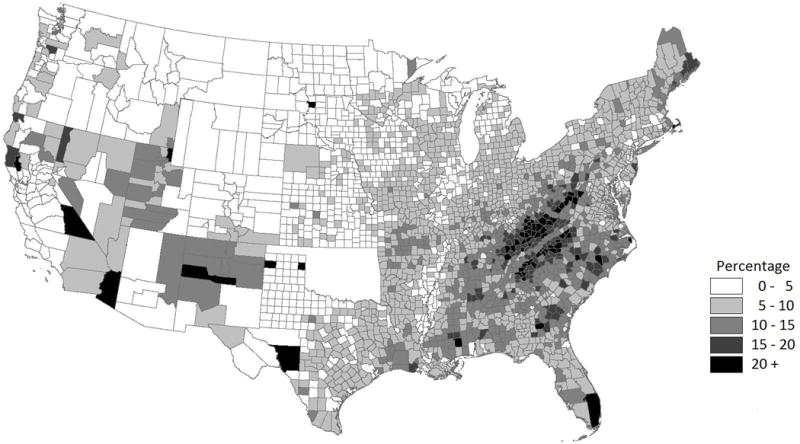

Means for variables in the regression models are shown in Table 2 for each census division to give some sense of geographic differentials and for the nation as a whole. The means for the dependent variable ranged from a low of 0.83 children less than five per married woman in New England to a high of 1.26 in the West South Central region. Only 6.3 percent of women had a potential mother-in-law living within the closest 10 households, while 2.9 and 3.3 percent had a mother or mother-in-law co-residing in the household, respectively. Generally speaking, there were proportionately more potential mothers-in-law in nearby households and co-residing mothers and mothers-in-law in eastern census regions, consistent with known patterns of migration of younger generations to the western frontier and the preference of older generations to remain in or near their long-term homes. The finding is also consistent with skewed regional sex ratios—men outnumbered women in the west and women outnumbered men in the east—and greater proportions of unmarried women in the east (Hacker, Hilde and Jones 2010). More detail can be seen in figure 1, which maps the percentage of potential nearby mothers-in-law by county. In addition to the east-west gradient noted above, the map reveals pockets of relatively high potential in-law availability in the Appalachian Mountains, the Carolina “backcountry”—areas known to have populations with high levels of Scots-Irish ancestry (Fischer 1989)— and counties in the West dominated by Mormon settlers and early settlers to Oregon Territory. Areas of low kin availability can be seen in most other counties in the Mountain, Pacific, and West North-Central census regions, which were only recently settled in 1880. Men and women of child-bearing age in this region were likely to have left parents behind in other regions.

Table 2.

Means of Variables in Regression Models by Census Division

| Region | Nation | New England | Mid Atlantic | E. North Central | W. North Central | South Atlantic | E. South Central | W. South Central | Mountain | Pacific | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Own Children Less than Five | 1.071 | 0.833 | 0.952 | 1.017 | 1.121 | 1.226 | 1.222 | 1.258 | 1.121 | 1.041 | |

| Covariates associated with Potential Childrearing Assistance | |||||||||||

| Co-resident mother | 0.029 | 0.042 | 0.034 | 0.026 | 0.023 | 0.029 | 0.026 | 0.025 | 0.017 | 0.023 | |

| Co-resident mother-in-law | 0.033 | 0.048 | 0.035 | 0.030 | 0.026 | 0.037 | 0.034 | 0.027 | 0.015 | 0.016 | |

| Other co-resident females age 11 and older | 0.585 | 0.583 | 0.579 | 0.586 | 0.571 | 0.615 | 0.614 | 0.534 | 0.467 | 0.594 | |

| Potential mother-in-law in +/− 5 households | 0.063 | 0.064 | 0.052 | 0.059 | 0.047 | 0.091 | 0.090 | 0.055 | 0.056 | 0.019 | |

| Covariates associated with Economic Readiness | |||||||||||

| Mother’s Labor Force Participation | 0.043 | 0.028 | 0.020 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.106 | 0.105 | 0.086 | 0.016 | 0.016 | |

| Father’s Occupational Group | |||||||||||

| Professional, Technical | 0.029 | 0.028 | 0.031 | 0.033 | 0.032 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.027 | 0.032 | 0.046 | |

| Farmers and Farm Operatives | 0.424 | 0.187 | 0.198 | 0.457 | 0.615 | 0.477 | 0.603 | 0.597 | 0.311 | 0.334 | |

| Managers, Official, Proprietors | 0.066 | 0.090 | 0.096 | 0.068 | 0.060 | 0.037 | 0.031 | 0.039 | 0.074 | 0.121 | |

| Clerical and Sales | 0.032 | 0.046 | 0.052 | 0.034 | 0.026 | 0.019 | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.027 | 0.046 | |

| Craftsmen | 0.136 | 0.196 | 0.215 | 0.148 | 0.103 | 0.087 | 0.058 | 0.055 | 0.133 | 0.161 | |

| Apprentices, Operatives | 0.103 | 0.258 | 0.175 | 0.094 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.033 | 0.025 | 0.153 | 0.128 | |

| Service Workers | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.022 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.013 | 0.025 | |

| Farm Laborers | 0.052 | 0.026 | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.016 | 0.122 | 0.112 | 0.085 | 0.046 | 0.018 | |

| Laborers | 0.126 | 0.131 | 0.164 | 0.111 | 0.073 | 0.155 | 0.101 | 0.127 | 0.191 | 0.104 | |

| No Occupational Response | 0.017 | 0.022 | 0.019 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.021 | 0.018 | |

| Average Value of Farms in County ($10,000) | 0.365 | 0.435 | 0.635 | 0.331 | 0.214 | 0.384 | 0.125 | 0.110 | 0.239 | 0.583 | |

| Proportion of children age 8-14 in school | 0.535 | 0.687 | 0.608 | 0.632 | 0.614 | 0.350 | 0.364 | 0.300 | 0.371 | 0.578 | |

| Covariates associated with Cultural “Willingness” | |||||||||||

| Proportion of Children Biblically Named | 0.301 | 0.268 | 0.314 | 0.260 | 0.272 | 0.351 | 0.350 | 0.321 | 0.254 | 0.267 | |

| Race and Nativity | |||||||||||

| White | 0.883 | 0.992 | 0.986 | 0.987 | 0.973 | 0.634 | 0.679 | 0.694 | 0.992 | 0.995 | |

| Black | 0.117 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.027 | 0.366 | 0.321 | 0.306 | 0.008 | 0.005 | |

| Native Born White of Native Parentage | 0.599 | 0.539 | 0.475 | 0.479 | 0.524 | 0.895 | 0.842 | 0.706 | 0.445 | 0.363 | |

| Irish | 0.076 | 0.186 | 0.156 | 0.056 | 0.051 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.015 | 0.047 | 0.150 | |

| German | 0.094 | 0.021 | 0.131 | 0.161 | 0.123 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.106 | |

| British | 0.040 | 0.055 | 0.063 | 0.049 | 0.040 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.185 | 0.079 | |

| Canadian | 0.029 | 0.109 | 0.022 | 0.044 | 0.032 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.034 | 0.052 | |

| Scandinavian | 0.015 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.022 | 0.055 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.064 | 0.019 | |

| French | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.015 | |

| Other Foreign Born | 0.019 | 0.007 | 0.017 | 0.028 | 0.030 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.029 | 0.049 | 0.055 | |

| Second Generation Irish | 0.027 | 0.029 | 0.048 | 0.029 | 0.027 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.031 | |

| Second Generation German | 0.023 | 0.003 | 0.032 | 0.040 | 0.026 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.018 | |

| Second Generation British | 0.070 | 0.040 | 0.074 | 0.092 | 0.087 | 0.031 | 0.054 | 0.081 | 0.081 | 0.090 | |

| Second Generation Canadian | 0.007 | 0.018 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.013 | |

| Second Generation Scandinavian | 0.056 | 0.026 | 0.052 | 0.073 | 0.072 | 0.027 | 0.051 | 0.077 | 0.053 | 0.067 | |

| Second Generation French | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.005 | |

| Second Generation Other Foreign Born | 0.037 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.035 | 0.040 | 0.022 | 0.081 | 0.125 | 0.028 | 0.040 | |

| Other Covariates | |||||||||||

| Residence Type | |||||||||||

| Rural | 0.817 | 0.712 | 0.707 | 0.807 | 0.834 | 0.915 | 0.921 | 0.894 | 0.947 | 0.881 | |

| Urban less than 10,000 | 0.053 | 0.034 | 0.070 | 0.084 | 0.052 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.029 | 0.013 | 0.038 | |

| Urban 10,000-100,000 | 0.077 | 0.227 | 0.100 | 0.073 | 0.063 | 0.041 | 0.034 | 0.018 | 0.040 | 0.080 | |

| Urban, 100,000+ | 0.053 | 0.027 | 0.122 | 0.036 | 0.052 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.059 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Demographic Control Variables | |||||||||||

| Mother’s Age 20-24 | 0.149 | 0.095 | 0.115 | 0.136 | 0.152 | 0.182 | 0.197 | 0.215 | 0.191 | 0.140 | |

| Age 25-29 | 0.206 | 0.179 | 0.194 | 0.203 | 0.207 | 0.217 | 0.223 | 0.233 | 0.230 | 0.197 | |

| Age 30-34 | 0.198 | 0.199 | 0.203 | 0.199 | 0.203 | 0.191 | 0.189 | 0.191 | 0.203 | 0.202 | |

| Age 35-39 | 0.185 | 0.204 | 0.197 | 0.188 | 0.185 | 0.174 | 0.169 | 0.161 | 0.170 | 0.194 | |

| Age 40-44 | 0.147 | 0.177 | 0.161 | 0.152 | 0.142 | 0.134 | 0.127 | 0.117 | 0.123 | 0.155 | |

| Age 45-49 | 0.115 | 0.147 | 0.130 | 0.122 | 0.111 | 0.101 | 0.096 | 0.084 | 0.083 | 0.113 | |

| Age Differential from Spouse | 5.457 | 4.710 | 4.689 | 5.413 | 5.705 | 5.747 | 5.974 | 6.269 | 6.733 | 7.643 | |

| Prior Fertiity (number of children age 5 and older) | 2.230 | 1.959 | 2.096 | 2.228 | 2.301 | 2.377 | 2.415 | 2.270 | 2.047 | 2.239 |

Notes: Universe includes all currently married women age 20-49 with spouse present with one or more own child with a valid first name.

Figure 1.

Percentage of currently married women age 20–49 living +/− 5 households from a potential mother-in-law, United States, 1880

One of the most consistent findings of American historical demographers is the pattern of high fertility on the nation’s western frontier, where land was readily available, farm prices were low, and parents could anticipate easily endowing all surviving children with nearby farms, and low fertility in long-settled areas near the eastern seaboard, where land for viable farms was scare and average farm prices were high (e.g., Yasuba 1962; Easterlin 1976; Easterlin, Alter, and Condran 1978). Although couples in eastern census divisions presumably benefitted from more assistance from nearby family members, the economic conditions that pushed some couples westward likely suppressed fertility among those who remained. And although couples in western census divisions presumably received less assistance from nearby family members, the low farm prices that pulled couples toward the frontier likely contributed to higher fertility. We control for this potential bias by introducing county farm prices in the models and by applying fixed effects at the SEA level to control for any remaining unmeasured heterogeneity.

6. Poisson analysis

The results of the Poisson regressions, shown in Table 3, identified a diverse set of marital fertility correlates. With a few exceptions, the results for the economic and demographic covariates were consistent with expectations. Relative to women married to farmers, women married to men in non-farm occupations had fewer children less than age 5 in the household. As expected, couples living in counties with high farm prices had lower fertility. More urban areas were associated with lower net marital fertility and older women, unsurprisingly, had fewer children than the reference group of married women age 20-24. The urban-rural differentials in fertility shown in Table 3 were likely driven by higher infant and childhood mortality rates in urban areas. In 1900, residence in a city of 5,000 or more individuals was associated with 20-36% higher infant and child mortality rates relative to the reference group of cities with 1,000-4,999 inhabitants (Preston and Haines 1991: 168). Although environmental conditions in cities were deteriorating in the late nineteenth century, differentials were likely large enough in 1880 to account for most, if not all, of the fertility differentials observed.

Table 3.

Poisson Regression of Recent Net Marital Fertility

| Model | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | None | SEA | None | SEA |

| Additional Universe Restriction | None | None | NBNP | NBNP |

| Coef. sig. | Coef. sig. | Coef. sig. | Coef. sig. | |

| Covariates associated with Potential Childrearing Assistance | ||||

| Co-resident mother | −0.027*** | −0.022*** | −0.026*** | −0.019*** |

| Co-resident mother-in-law | −0.005* | 0.005* | −0.003 | 0.013*** |

| Other co-resident females age 11 and older | −0.035*** | −0.033*** | −0.037*** | −0.035*** |

| Potential mother-in-law in +/− 5 households | 0.022*** | 0.016*** | 0.020*** | 0.017*** |

| Covariates associated with Economic “Readiness” | ||||

| Mother’s Labor Force Participation | −0.118*** | −0.108*** | −0.111*** | −0.094*** |

| Father’s Occupational Group | ||||

| Professional, Technical | −0.133*** | −0.118*** | −0.103*** | −0.088*** |

| Farmers and Farm Operatives | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Managers, Official, Proprietors | −0.174*** | −0.149*** | −0.180*** | −0.143*** |

| Clerical and Sales | −0.184*** | −0.150*** | −0.174*** | −0.126*** |

| Craftsmen | −0.122*** | −0.097*** | −0.123*** | −0.096*** |

| Apprentices, Operatives | −0.100*** | −0.067*** | −0.123*** | −0.075*** |

| Service Workers | −0.164*** | −0.134*** | −0.144*** | −0.120*** |

| Farm Laborers | −0.028*** | −0.018*** | −0.023*** | −0.013*** |

| Laborers | −0.066*** | −0.045*** | −0.055*** | −0.040*** |

| No Occupational Response | −0.160*** | −0.142*** | −0.132*** | −0.111*** |

| Average Value of Farms in County ($10,000) | −0.045*** | −0.037*** | −0.060*** | −0.047*** |

| Proportion of children age 8-14 in school | −0.279*** | −0.013** | −0.327*** | 0.002 |

| Covariates associated with Cultural “Willingness” | ||||

| Proportion of children biblically named | 0.067*** | 0.028*** | 0.057*** | 0.011*** |

| Race and Nativity | ||||

| Native Born White of Native Parentage | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Black | 0.029*** | 0.001 | 0.013*** | −0.012*** |

| Irish | 0.295*** | 0.344*** | ||

| German | 0.257*** | 0.288*** | ||

| British | 0.123*** | 0.156*** | ||

| Canadian | 0.117*** | 0.187*** | ||

| Scandinavian | 0.292*** | 0.303*** | ||

| French | 0.177*** | 0.209*** | ||

| Other Foreign Born | 0.215*** | 0.256*** | ||

| Second Generation Irish | 0.107*** | 0.137*** | ||

| Second Generation German | 0.112*** | 0.128*** | ||

| Second Generation British | −0.017*** | 0.019*** | ||

| Second Generation Canadian | 0.003 | 0.069*** | ||

| Second Generation Scandinavian | 0.003 | −0.027*** | ||

| Second Generation French | 0.071*** | 0.095*** | ||

| Second Generation Other Foreign Born | −0.001 | 0.006** | ||

| Other Covariates | ||||

| Residence Type | ||||

| Rural | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Urban less than 10,000 | −0.070*** | −0.072*** | −0.112*** | −0.106*** |

| Urban 10,000-100,000 | −0.086*** | −0.061*** | −0.166*** | −0.116*** |

| Urban, 100,000+ | −0.061*** | −0.023*** | −0.099*** | −0.058*** |

| Demographic Control Variables | ||||

| Mother’s Age 20-24 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Age 25-29 | −0.070*** | −0.059*** | −0.092*** | −0.075*** |

| Age 30-34 | −0.296*** | −0.277*** | −0.334*** | −0.302*** |

| Age 35-39 | −0.547*** | −0.520*** | −0.587*** | −0.542*** |

| Age 40-44 | −1.011*** | −0.978*** | −1.038*** | −0.983*** |

| Age 45-49 | −1.971*** | −1.936*** | −1.959*** | −1.900*** |

| Age Differential from Spouse | −0.011*** | −0.011*** | −0.011*** | −0.010*** |

| Prior Fertiity (number of children age 5 and older) | 0.069*** | 0.063*** | 0.077*** | 0.067*** |

| Number of observations | 5,435,171 | 5,435,171 | 3,092,056 | 3,092,056 |

| Log-likelihood | −6436041 | −6414179 | −3634058 | −3614565 |

| Prob>Chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

Notes: Poisson regression. The dependent variable is the number of own children less than age five in the household. Interactions between nativity variables and proportion of children biblically named (centered at mean) and nativity variables and potential childrearing assistance variables not shown. Universe includes all currently married women age 20-49 with spouse present, with one or more own child in the household with a valid first name. “SEA” is State Economic Areas. See text. “NBNP” is native-born couples with native-born parents.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

The results for the variables associated with kin proximity were less consistent with expectations. Consistent with our expectations, women with a potential mother-in-law nearby had about 2 percent more children, all else being equal, than women without potential mothers-in-law nearby. Although the result was modest and applicable to only a subset of women in the dataset, the coefficient is likely biased downwards by our failure to identify all potential mothers-in-law. Many married women no doubt received assistance from potential mothers-in-law living nearby but outside our search window of the 10 nearby households. The coefficient is also biased downwards by our failure to identify all potential nearby childrearing assistance outside the household, most notably focal women’s own mothers, but also her aunts, sisters, sisters-in-law, some aunts-in-law, and other relatives.

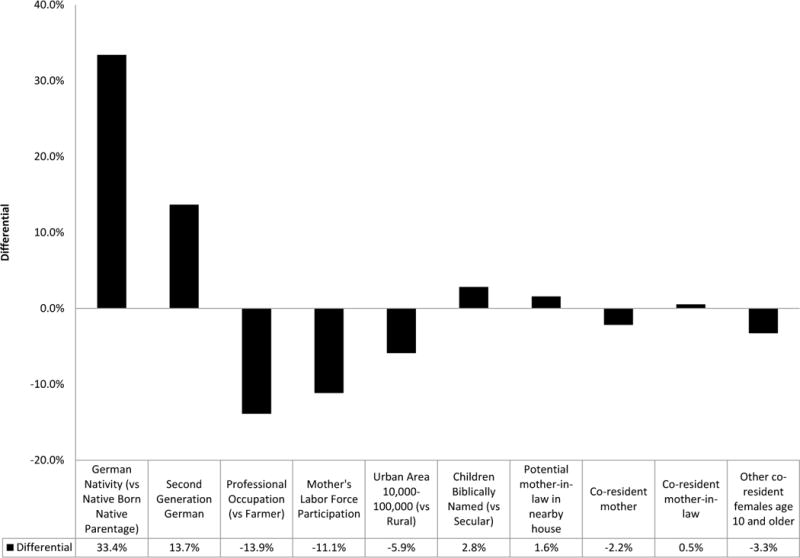

Contrary to our expectations, however, co-residence with females age 11 and older (who were not mothers or mothers-in-law) was negatively associated with focal women’s fertility. Although the substantive result was modest compared to other factors (see figure 2, which highlights the substantive impact of a few selected variables on women’s fertility) – co-residence with another female age 11 and older reduced fertility about 3 percent — it was contrary to our expectation that the availability of potential helpers would act as a pro-natal force. This result suggests that the economic and childrearing assistance these women presumably provided was counterbalanced by other factors. Although our cross-sectional model does not allow us to estimate these factors, a few mechanisms may have played a role. Given our control for women’s prior fertility in the model, women with more females age 11 and above typically had fewer males age 11 and above. If these males contributed significant familial and economic help to the family, the childrearing assistance provided by older females may have been offset.4 Additional possibilities include the potential for greater conflict or competition for resources in larger households, which has been shown to be relevant to childbearing in other contexts (e.g., Flinn 1989; Strassmann 2011, Moya and Sear 2014), and the potential role of duration of marriage and its relationship to stopping behavior. Although we have no precise measurement in the data, women with more co-resident females age 11 and older likely had longer marriages than women without co-resident older females.

Figure 2.

Selected fertility differentials from model results (model 2), United States, 1880

Also contrary to our expectations, women’s co-residence with their own mothers was associated with fewer children (co-residence with mothers-in-law was weakly associated with more children). Again, our cross-sectional model does not allow us to estimate what factors may have been responsible for the unexpected result. We note, however, that other researchers have shown that mothers’ concerns about the health risks of excessive childbearing on their daughters (maternal depletion) may result in her discouraging rapid childbearing (Sear and Coall 2011). The presence of one’s own mother or other individuals in the household may have also made privacy difficult and reduced coital frequency. There may be unobserved selection biases at play as well. If mothers and mothers-in-law in poverty or poor health were more likely to live with their children, for example, they may represent a burden for women in the model, not a source of assistance. Historians have typically argued that elderly parents who were unable to care for themselves, especially widowed mothers, either had an adult child return to their household to live with them or moved into a child’s household (e.g., Hareven 1994). Ruggles (2003), however, has argued that co-residence of the aged with one of their surviving children was near universal in the nineteenth-century United States and that the poor and sick were more likely to live alone, not less likely. Longitudinally-linked census samples—now in construction at the Minnesota Population Center—will allow us to untangle potential selection biases by observing the impact of changes in living arrangements with changes in fertility.

The model results were consistent with the hypothesis that a lack of cultural willingness was an impediment to the practice of marital fertility control among some families. Irish, German, and Scandinavian couples had approximately 30-40% higher net marital fertility rates than native-born white couples of native parentage, French and Canadian couples had 20-25% higher rates, while British couples had 17% higher rates. Previous investigators had conceded that some of the observed differentials between native-born and foreign born women may have been due to SES differentials or residence location. Given our inclusion of controls for occupation and urban residence and the use of SEA fixed effects in the model, however, the large differentials in fertility by nativity suggests a greater lack of cultural willingness to practice marital fertility control among most foreign-born couples relative to native-born couples. Fertility differentials among second generation couples relative to native-born whites of native parentage were less than half of the differentials among first generation immigrants, suggesting rapid assimilation to American childbearing norms. Among second generation Scandinavian and British couples, fertility was approximately equal to or lower than the reference group.

Parental religiosity, as proxied by parents’ choice of biblical names for their children, also appears to have been a significant obstacle to practice of marital fertility control. All else being equal, couples choosing biblical names for their children had 3% more children under age five than parents relying on secular names. The true impact of parental religiosity was likely larger. As previously noted, the child naming variable is believed to be an imperfect proxy of parental religiosity, and therefore understates its importance.

The restriction of the models to the native-born of native parentage (NBNP) population (models 3 and 4) had little impact on most coefficients. The coefficients for the co-residence of mothers and other females age 11 and older remained modestly negative, while the coefficients for women with a nearby potential mother-in-law remained modestly positive. The coefficient for the use of biblical names remained positive, but indicated that parents relying on biblical names had only 1 more children than parents relying on secular names.

7. Conclusion

Research on the U.S. fertility transition typically ignores the potential contribution of cultural and familial influences. In this paper we relied on the new complete-count 1880 census microdata database (Minnesota Population Center 2015) to study the role of culture and the family in the early phase of the fertility transition, including the investigation of whether proximity to nearby kin influenced couples’ fertility behavior. By examining the surname, age, and sex of members in adjacent households, we were able to construct a measure of potential mothers-in-law for all women of childbearing age in the dataset. We also constructed measures indicating the co-residence of mothers, mothers-in-law, and other females age 11 and older. The results indicated that while proximity of mothers-in-law had a positive impact on women’s fertility—consistent with hypotheses that the availability of assistance is positively correlated with fertility—co-residence with mothers, older daughters, and other women had a negative impact. This negative impact, however, may be biased by unobserved selection biases, and we suggest the need for longitudinal studies using linked census datasets, which are now under construction at the University of Minnesota.

We also examined the impact of nativity and a proxy of parental religiosity on fertility. Both proved to be significant correlates of marital fertility. Couples’ nativity exerted the strongest influence of all independent variables in the model. Couples born in Germany, Ireland and Scandinavian countries had approximately 30-40% more children, all else being equal, than native-born white couples of native parentage. These large differentials, even after controlling for economic, demographic and other suspected covariates, suggest that culture played a major role in couples’ decisions to control their fertility. All else being equal, native-born with couples with native-born parents proved more willing to act on incentives to reduce their fertility, while foreign-born parents proved less willing. In most cases, fertility differentials between native-born couples of native parentage and second generation couples were less than half of the differentials estimated for first born couples. Parents who chose a higher proportion of biblical names for their children had higher fertility rates than parents who relied on secular names, suggesting a positive relationship between parental religiosity and marital fertility.

Overall, our results demonstrate the need for more inclusive models of fertility behavior. Too often, prior research has focused exclusively on economic factors. Although economic motivations were clearly important, couples’ fertility decisions depended on a host of factors, including proximity to kin, nativity and religiosity. We conclude that failure to consider the role of the family will result in an incomplete understanding of the couples’ decisions on the number and timing of their children.

Acknowledgments

Research was supported in part by funds provided to the Minnesota Population Center from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grants R24-HD041023 and from NICHD Grants K01-HD052617 and R01-HD082120. The authors received valuable feedback from participants at the Power of the Family conference in Wageningen in October 2015, organized by Hilde Bras. We received additional valuable feedback at the Population Association of America and International Union for the Scientific Study of Population meetings in 2016, and a Minnesota Population Center seminar in 2017. We thank the two anonymous referees for their suggestions.

Footnotes

For information on data access, please visit https://usa.ipums.org/usa/complete_count.shtml

94% of native-born wives had native-born husbands, while 90% of foreign-born wives had foreign-born husbands.

With the possible exception of the urban-rural differentials discussed below, differentials in the number of children less than age five in the household are believed to result primarily from differentials in marital fertility rather than from differentials in infant and child mortality. See discussion in Dribe et al. 2014 and Scalone and Dribe 2017. Unfortunately, we know little about infant and child mortality in the five years prior to the 1880 census.

Model results without the introduction of a control for women’s prior fertility (not shown) indicated a modest positive impact of the number of co-resident females age 11 and older on women’s fertility. It is likely, however, that this result was biased by focal women’s fecundity.

Contributor Information

J. David Hacker, University of Minnesota.

Evan Roberts, University of Minnesota.

References

- Allen N. Changes in New England Population. Lowell, Mass: Stone, Huse & Co., Printers; 1877. [Google Scholar]

- Atack J, Bateman F. To Their Own Soil: Agriculture in the Antebellum North. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie JF. Contraception and abortion in 19th-century America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess EW, Cottrell LS. Predicting Success or Failure in Marriage. New York: Prentice Hall; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess EW, Wallin P. Engagement and marriage. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Carter SB, Ransom RL, Sutch R. Family matters: The life-cycle transition and the antebellum American fertility decline. In: Guinnane TW, Sundstrom WA, Whatley W, editors. History Matters: Essays on Economic Growth, Technology, and Demographic Change. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2004. pp. 271–327. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves M. Secularization as declining religious authority. Social Forces. 1994;72(3):749–774. [Google Scholar]

- Coale AJ, Zelnik M. New Estimates of Fertility and Population in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Degler CN. At Odds: Women and the family in America from the Revolution to the present. New York: Oxford University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Dribe M, Hacker JD, Scalone F. Socioeconomic Status and Net Fertility during the Fertility Decline: A Comparative Analysis of Canada, Iceland, Sweden, Norway and the United States. Population Studies. 2014;68(2):135–149. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2014.889741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RS. Population change and farm settlement in the northern United States. Journal of Economic History. 1976;36(1):45–75. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RA, Alter G, Condran G. Farms and farm families in old and new areas: The northern United States in 1860. In: Hareven TK, Vinovskis M, editors. Family and Population in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1978. pp. 22–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer DH. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Flinn MV. Household composition and female reproductive strategies in a Trinidadian village. In: Rasa AE, Vogel C, Voland E, editors. The Sociobiology of Sexual and Reproductive Strategies. London/New York: Chapman and Hall; 1989. pp. 206–233. [Google Scholar]

- Forste R, Tienda M. What’s behind racial and ethnic fertility differentials? Population and Development Review. 1996;22(Suppl):109–133. [Google Scholar]

- Forster C, Tucker GSL. Economic opportunity and white American fertility ratios, 1800–1860. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde J, McCants A. Fertility, marriage, and culture: Demographic processes among Norwegian immigrants to the rural Middle West. The Journal of Economic History. 1995;55(4):860–888. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberger AS. A Course in Econometrics. London: Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider C, Uhlenberg P. Minority group status and fertility. The American Journal of Sociology. 1969;74(4):361–372. doi: 10.1086/224662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryeva A, Ruef M. The historical demography of racial segregation. American Sociological Review. 2015;80(4):814–842. [Google Scholar]

- Guest AM. Social structure and U.S. inter-state fertility differentials in 1900. Demography. 1981;18(4):465–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest AM, Tolnay SE. Children’s roles and fertility: Late nineteenth-century United States. Social Science History. 1983;9(4):355–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker JD. Child naming, religion, and the decline of marital fertility in nineteenth-century America. History of the Family: An International Quarterly. 1999;4(3):339–365. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker JD. Rethinking the “early” decline of marital fertility in the United States. Demography. 2003;40(4):605–620. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker JD. Ready, willing and able? Impediments to onset of marital fertility decline in the United States. Demography. 2016;53(6):1657–1692. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0513-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker JD, Hilde LR, Jones JH. The effect of the Civil War on southern marriage patterns. Journal of Southern History. 2010;76(1):39–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines MR. Occupation and social class during fertility decline: Historical perspectives. In: Gillis JR, Tilly LA, Levine D, editors. The European experience of changing fertility. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell; 1992. pp. 193–226. [Google Scholar]

- Haines MR, Hacker JD. Spatial aspects of the American fertility transition in the nineteenth century. In: Gutmann MP, Deane GD, Sylvester KM, Merchant ER, editors. Navigating time and space in population studies. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hareven TK. Aging and generational relations: A historical and life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology. 1994;20:437–461. [Google Scholar]

- Hareven TK, Vinvoskis MA. Marital fertility, ethnicity, and occupation in urban families: An analysis of South Boston and the South End in 1880. Journal of Southern History. 1975;8(3):69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes K, O’Connell JF, Blurton Jones NG. Hardworking Hadza grandmothers. In: Standen V, Foley RA, editors. Comparative Socioecology: The behavioural ecology of humans and other mammals. Oxford: Blackwell; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hrdy SB. Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jones LE, Tertilt M. An economic history of fertility in the U.S.: 1826–1960. Frontiers in Family Economics. 2008;1:165–230. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings JA, Sullivan AR, Hacker JD. Intergenerational transmission of reproductive behavior during the onset of the fertility transition in the United States: New evidence from the Utah Population Database. Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 2012;42(4):543–569. doi: 10.1162/jinh_a_00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JR. Immigrant selectivity and fertility adaptation in the United States. Social Forces. 1988;67(1):108–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JR. Immigrant and native fertility during the 1980s: Adaptation and expectations for the future. The International Migration Review. 1994;28(3):501–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Ruggles S. American immigration, fertility, and race suicide at the turn of the century. Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 1990;20:347–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepp SE. Revolutionary conceptions: Women, fertility, & family limitation in America 1760–1820. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JT. Religiousness, family relationships, and family values in Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish families. Marriage and Family Living. 1960;22(4):341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Leasure JW. La baisse de la fécondité aux État-Unis de 1800 a 1860. Population. 1982;37(3):607–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R, Neidert L. The second demographic transition in the United States: Exception or textbook example? Population and Development Review. 2006;32(4):669–698. [Google Scholar]

- Logan T, Parman J. The national rise in residential segregation. Journal of Economic History. 2017;77(1):127–170. [Google Scholar]