Abstract

Background.

Surveys show GPs use placebos in clinical practice and reported prevalence rates vary widely.

Aim.

To explore GPs’ perspectives on clinical uses of placebos.

Design and setting.

A web-based survey of 783 UK GPs’ use of placebos in clinical practice.

Methods.

Qualitative descriptive analysis of written responses (‘comments’) to three open-ended questions.

Results.

Comments were classified into three categories: (i) defining placebos and their effects in general practice; (ii) ethical, societal and regulatory issues faced by doctors and (iii) reasons why a doctor might use placebos and placebo effects in clinical practice. GPs typically defined placebos as lacking something, be that adverse or beneficial effects, known mechanism of action and/or scientific evidence. Some GPs defined placebos positively as having potential to benefit patients, primarily through psychological mechanisms. GPs described a broad array of possible harms and benefits of placebo prescribing, reflecting fundamental bioethical principles, at the level of the individual, the doctor–patient relationship, the National Health Service and society. While some GPs were adamant that there was no place for placebos in clinical practice, others focused on the clinically beneficial effects of placebos in primary care.

Conclusion.

This study has elucidated specific costs, benefits and ethical barriers to placebo use as perceived by a large sample of UK GPs. Stand-alone qualitative work would provide a more in-depth understanding of GPs’ views. Continuing education and professional guidance could help GPs update and contextualize their understanding of placebos and their clinical effects.

Keywords: Attitudes, general practice, health knowledge, placebo effects, placebos, qualitative research.

Introduction

So-called ‘placebo’ treatments have been shown to be effective for treating some symptoms managed in primary care, including musculoskeletal pain (1), irritable bowel syndrome (2) and depression (3). There is debate over the role of placebos in clinical practice (4) but there are few data on practitioners’ perspectives to guide such analyses. Existing data are predominantly quantitative and national surveys have now established that doctors routinely use placebos and/or attempt to elicit placebo effects in clinical practice for example in the USA (5), Germany (6) and Switzerland (7). However, reasons why doctors use placebos are not well understood and the prevalence of use varies greatly both between and within surveys, depending in no small part on how placebos and their effects are defined for respondents.

Many surveys focus on placebos as objects (rather than placebo effects) and go on to distinguish between pure and impure placebos (5–7). Pure placebos include ‘dummy’ capsules used in placebo-controlled clinical trials and saline injections and can be defined as pharmacologically inert for the condition being treated, i.e. if they were given without a patient’s knowledge they would have no effect on symptoms. In comparison, the designation of ‘impure placebos’ might include antibiotics, when prescribed for perceived viral infection, and multivitamins, in the absence of vitamin deficiency; impure placebos are considered to not have pharmacological benefit for the patient’s condition but might have proven benefit for other conditions. However, the pure–impure placebo distinction is little more than a rough guide and can break down on close scrutiny. In their systematic review, Fassler et al. (8) highlighted the lack of consensus regarding ‘impure’ placebos and concluded that while the use of placebos in clinical practice is not negligible, further research is needed to provide reliable estimates and clearer understandings of doctors’ attitudes and practices. There is also little consensus regarding the definition of placebo effects although a semiotic approach may offer a way forward, in which placebo effects can be defined as ‘the direct therapeutic effects associated with the perception and interpretation of signs’ in the clinical encounter (9).

Most studies on doctors’ use of placebo effects have employed quantitative methods (8) but qualitative methods are better suited to exploring a topic in-depth from the perspective of a particular group of people. Fassler et al. (8) identified only two qualitative studies in this field. Comaroff’s ethnography of prescribing in general practice in Wales in the 1970s showed how prescribing substances that might be considered placebos is a complex social act, which can help GPs to manage their own uncertainties, the consultation ritual and duration, and patients’ expectations (10). In the context of a large US-based clinical trial, Schwartz (11) found that a sizeable minority of physicians were explicitly prescribing drugs that were not indicated in conditions for which they were prescribed in an attempt to generate a placebo effect. More recently, 12 Swiss physicians were interviewed qualitatively about placebos; participants tended to focus on pure placebos and perceived a need for ethical guidance in this area (12). In the UK, legal and ethical guidance concerning placebos focuses on placebo use in clinical research not clinical practice. Given the potential insights to be gained by using qualitative methods, we incorporated a series of open-ended questions into a primarily quantitative survey of UK-based GPs’ use of placebos. We aimed to provide a preliminary exploration of GPs’ perspectives on clinical uses of placebos and their effects.

Methods

Main survey

A comprehensive description of the survey methods and quantitative results has been published previously (13). In brief, we conducted an anonymous nationwide web-based survey of UK GPs (response rate = 46%) (13). Ethical approval was obtained from the host institution (University of Oxford). Following earlier surveys (5–7), the questionnaire distinguished between pure and impure placebos. Out of 783 participants, a minority used pure placebos (12% had used them at least once, 1% used them weekly). However, almost all (97%) had used impure placebos at least once while a large majority (77%) used them weekly. Most, but not all, found placebos ethically acceptable in some circumstances (66% for pure, 84% for impure). These quantitative findings are broadly consistent with other surveys (8).

Qualitative component

The survey instrument also included open-ended questions that allowed participants to respond in more detail (Table 1). Additional open-ended questions that allowed participants to specify an ‘other’ option in response to multiple choice questions were not included in the current analysis. Responses to the questions in Table 1 (henceforth ‘comments’) were collated and imported into Atlas.ti 6.2 for analysis. A total of 926 comments (15179 words) were received from 420 GPs (53.6% of survey respondents). GPs who left comments were not significantly different to those who did not leave comments in terms of their characteristics or responses to the quantitative questions (Table 2). Comments were typically brief (one phrase or sentence) and participants would often comment on one aspect of placebos but not on others, precluding any detailed analysis of the relationships between and among categories or themes. Therefore, a descriptive approach to data analysis is appropriate (14).

Table 1.

Open-ended survey questions that elicited the comments analysed here

| If you have any comments about reasons for using pure or impure placebos please write them in the box below. |

| If you have time and would like to do so, please write your definition of placebos in the box below. |

| If you have any comments about the ethical use of pure or impure placebos, please write them in the box below. |

Table 2.

Comparing GPs who did (n = 420) and did not (n = 363) supply qualitative comments

| Characteristic | Qualitative comments | No qualitative comments | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender and work | |||

| Gender: female, % (n) | 42.9% (180) | 47.1% (171) | χ2(1) = 1.422, P = 0.233 |

| Qualification year: M (SD) | 1992 (9) | 1994 (9) | t(781) = 1.951, P = 0.051 |

| Days/week in practice: M (SD) | 3.64 (1.06) | 3.78 (1.00) | t(781) = 1.822, P = 0.069 |

| Patients/week: M (SD) | 121.08 (61.82) | 124.59 (58.27) | t(781) = 0.814, P = 0.416 |

| Use of placebos | |||

| Have used pure placebos clinically: % (n) | 12.3% (54) | 11.6% (42) | χ2(1) = 0.30, P = 0.584 |

| Have used impure placebos clinically: % (n) | 96.9% (407) | 97.5% (354) | χ2(1) = 0.27, P = 0.603 |

| Believe placebos can be acceptablea | |||

| Pure placebos: % (n) | 68.3% (287) | 63.9% (232) | χ2(1) = 1.703, P = 0.192 |

| Impure placebos: % (n) | 84.5% (355) | 83.7% (304) | χ2(1) = 0.088, P = 0.766 |

aIn some circumstances.

We undertook thematic coding of the data (but not a full thematic analysis, given the limitations of the data) (15). FLB repeatedly read comments to achieve familiarization and then used an inductive, open coding process in which short descriptive labels (codes) were applied to each comment. Multiple codes were applied to comments that expressed multiple meanings. Comments and codes were reviewed and compared to identify similarities and differences. Similar codes were grouped into higher level categories to provide a descriptive summary of the comments. As a result of this process, three categories of comments were identified: defining placebos and their effects in general practice; ethical, societal and regulatory issues faced by doctors and reasons why a doctor might use placebos and their effects in clinical practice. Often comments were allocated to the category that most closely resembled the question that elicited them (e.g. responses to the question requesting comments on ethics of placebo use were often but not always categorized under ‘ethical, societal, and regulatory issues around placebos’). The categories are described below with illustrative comments selected for typicality and/or eloquence. Numbers in parentheses are identifiers that attribute illustrative comments to individual participants.

Results

Defining placebos and their effects in general practice

GPs commented on the contents of placebos, their effects, mechanisms of action and ‘evidence’. Illustrative examples of participants’ definitions of placebos are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Typical definitions of placebos written by survey respondents

| ‘Placebo is a treatment with no known effect but appears to work when this fact is not known by the patient’ (552) |

| ‘Substances with no proven clinical benefit in the area they are being used, but are unlikely to harm and could give at least psychological benefit’ (666) |

| ‘I perceive a placebo to be an intervention for which there is no evidence base of efficacy, nor pharmacological explanation for the same. It also an intervention which is known to have no adverse or potential adverse effect through its use’. (274) |

| ‘A substance that has no therapeutic medicinal benefit’ (97) |

| ‘A treatment or medication with no active ingredient that promotes a beneficial response in treating a medical condition’ (681) |

| ‘Something you give a patient to make them feel better that has no biological effect’ (164) |

Participants typically described placebos in terms of what they did not contain: organic, biological, physiological and/or chemical agents. They also described placebos as lacking ‘active ingredients’ and as ‘inert’ substances. The pure placebo sugar pill was often referred to as the archetypal placebo and concepts from drug trials, of the placebo as a fake or substitute pill, were also expressed. A few comments rejected the concept of ‘impure placebos’ used in the survey, arguing that only ‘pure’ placebos should be considered placebos.

Some comments linked placebos to the intentions of the provider and there was considerable diversity in implied benevolence: placebos were variously defined as substances used to fool the patient (primarily in drug trials), as substances used to please the patient, and as substances used in an attempt to benefit the patient. Of 24 comments that related deceptive prescribing to placebos, 21 suggested that deceptive prescribing is an essential, defining feature, of placebos.

Consistent with the dominant view that placebos contain no active ingredients, GPs typically described placebos as being either ineffective or incapable of causing harm and/or being ‘safe’. Somewhat surprisingly though, comments about the possible beneficial effects of placebos were also common, and many comments reproduced the contradiction (often debated in the literature) that is inherent in defining a substance as inert and then going on to describe its effects. For example, ‘Placebo is an inert substance that when taken by a person can have an effect on that person - either good or bad’ (503).

There was a similar divergence in views about how placebos work: the two dominant views were on the one hand that placebos, by definition, have no known pharmacological action, and on the other hand that placebos work through psychological mechanisms. Interestingly, almost every comment that evoked evidence-based medicine in relation to placebos (90 out of 94) referred to placebos as lacking any evidence of clinical effect.

In summary, the dominant definitions of placebos and their effects included the following features: placebo treatments are inert or inactive, they can have a positive but not a detrimental effect, they have no known pharmacological mechanism of action and there is no scientific evidence to prove they are effective. Typically then, comments were about what was absent, about what placebos are not, what they do not contain and what is not known about them. Views about the present features of placebos were less commonly expressed; these described placebos as having potential to benefit patients, primarily through psychological mechanisms.

Ethical, societal and regulatory issues faced by doctors

Many comments about the ethics of placebo were very brief in judging placebos to be ‘unethical’ but did not elaborate on this position. Such comments included: ‘inappropriate’, ‘I generally disagree with the use of these’ and ‘I think they are unethical’. Participants who provided a little more detail appeared to be engaging in a cost-benefit analysis to inform their judgements as to the ethical acceptability of placebos in clinical practice (see Table 4).

Table 4.

GP-perceived costs and benefits of using placebos in clinical practice

| Type of placebo | Perceived costs | Perceived benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Both (or not specified) | Endangering patient trust and doctor–patient relationships (through deception). Potential for legal ramifications. Financial cost. Medicalization (reinforcing inappropriate help-seeking behaviour and dependence on doctors/prescribing). Not giving an effective treatment. Not a long-term solution. | Positive effect on patient’s symptoms and/or psychological well-being and/or satisfaction. |

| Pure placebos | – | Lack of adverse effects. Low risk. Safe. |

| Impure placebos | Adverse effects. Interactions with other drugs. Increasing resistance (antibiotics). Promotes irrational beliefs (homeopathy). | – |

In relation to benefits, GPs commented about how they did or would use placebos in order to benefit patients in some way: ‘anything that can improve a patient’s wellbeing has to be good’ (91). In relation to costs, two related principles appeared to underpin GPs’ comments about the ethics of placebo use:

Do no harm (‘as long as they do no harm’, 393) and

Do not lie (‘should not lie to patients’, 339).

Arguing that pure placebos are ethically acceptable because they could benefit but could not harm patients can be seen as prioritizing the former principle. For example, ‘Primum non nocere; pure placebos may benefit patient psychologically whilst still adhering to this principle. The same cannot be said for impure placebos’ (482). Arguing that impure placebos are acceptable because they do not involve deceiving the patient can be seen as prioritizing the latter principle. Participants often appeared to assume, and some explicitly stated, that deception is a defining feature of pure placebo treatments (as it is in most placebo-controlled trials).

Using a pure placebo always involves an element of deceit on behalf of the prescriber, so are therefore never acceptable. Impure placebos can be described when prescribing them in a way that is not deceitful but simply holds out hope that they might help or have been known to help in the past, despite insufficient evidence to support their use. (626)

An emphasis on ‘do no harm’ appeared to involve seeing pure placebos as more acceptable than impure placebos, while an emphasis on ‘do not lie’ seemed to result in seeing impure placebos as more acceptable than pure placebos. Other comments appeared to reflect both principles in arguing that breaching the injunction to speak truthfully to patients does itself have the potential to do harm. In particular, participants commented on how prescribing pure placebos in a deceptive manner had not only potential to benefit patients but also potential to damage trusting doctor–patient relationships. Some comments thus had a dilemmatic quality to them, elucidating the multiple potential benefits and/or harms of placebo use and hinting at the complexity of clinical decision-making.

Pure placebos are unlikely to harm a patient per se, but have lots of potential to harm the Dr/Patient relationship. Impure placebos on the other hand have plenty of scope for causing harm, whilst often preserving a Dr/patient relationship (at least until the harm occurs!). (273)

Very difficult situation in current state of affairs. How can one justify the approach of withholding some information from the patient? At the same time we know that placebo can be effective in up to 20% situation. Is that enough? (79)

Considerable confusion and concern were expressed regarding the professional and legal status of placebos in clinical practice. This suggests a need for clear guidance and some participants explicitly called for official guidelines in this area:

It is a likely medico-legal nightmare (348)

I feel pure placebos may be acceptable in clinical practice if the legal issues around their use could be addressed and proper guidance issued (776)

Very difficult area would need GMC guidance (164)

Participants also commented, from a societal perspective, on the financial implications of placebo prescribing for the publicly funded National Health Service (NHS). At one extreme, participants saw potential for placebos to save the NHS money: ‘with limited resources they can’t be dismissed’ (142). At the other extreme, participants argued it is unacceptable to waste NHS resources on unproven therapies: ‘in NHS where money is short drugs must have an evidence base’ (271). There was some acceptance of patients deciding for themselves to spend their own money on placebos: ‘If patients want to spend their own money on things I regard as placebos that is their affair. I would be neglecting my responsibilities to both the patient and the tax payers funding the treatment by prescribing placebos’ (826).

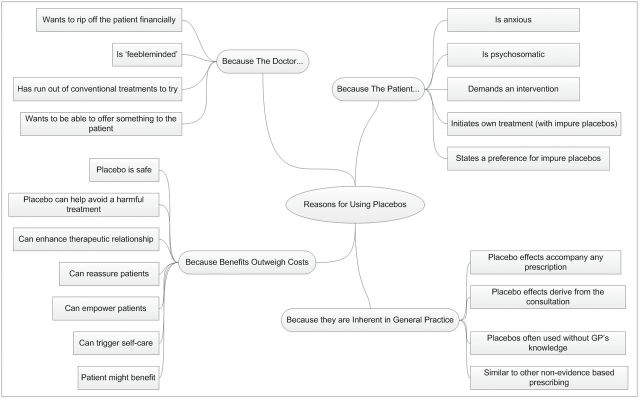

Reasons why a doctor might use placebos and placebo effects in clinical practice

GPs identified a number of distinct reasons why a doctor might use placebos and their effects in clinical practice (Fig. 1). A few GPs expressed starkly cynical attitudes towards doctors who use placebos, commenting on the ‘feeblemindedness’ of placebo prescribers and their dubious motives. Others saw the use of placebo treatments as somewhat more benevolent, attributing it to doctors’ frustrations of not having an effective conventional therapy available, wanting to offer something to patients and perceiving that patients expect to receive a prescription. More typically, comments about reasons for using placebos mirrored the comments related to the ethical acceptability of placebo use, in that GPs commented on how placebos are and can be used when their potential benefits outweigh the costs. However, unlike the comments about the ethics of placebos, talk about reasons for using placebos also mentioned individual patients, with GPs commenting on how placebo treatments might be used for some patients and conditions but not others. Some suggestions as to who would benefit most from placebo treatment (e.g. patients with psychosomatic conditions) appear consistent with a view of placebo effects as psychologically mediated.

Figure 1.

Reasons for using placebos in clinical practice, according to GPs

Some GPs appeared not to share an assumption underlying the survey—that using placebos and their effects is something of a special or unusual clinical decision. Instead, they saw placebo effects (but not pure placebos) as inherent in medical practice, arguing that a lack of evidence is not unusual in primary care and much of general practice would not be classed as evidence based: ‘Much of the commonly used treatments have no evidence base for their efficacy. This is often because there has been little or no research into their efficacy’ (290).

Some GPs challenged another fundamental assumption made in the survey, that clinical uses of placebos can be narrowly defined and understood with reference to the substance that is classified as a pure or impure placebo. This challenge was exemplified in comments about the ubiquity of placebo effects in general practice.

Everything I do or prescribe has some placebo quality. I deal with human beings and they are messy not like the things in textbooks. (154)

The art of medicine is about extracting the 50% or so of placebo effect from a treatment. It is practitioner/healer dependent and it is a power worth harnessing. (802)

These comments thus highlighted the ‘art of medicine’ and the role that clinical context, the GP, their words and their manner can play in delivering placebo effects alongside specific drug effects.

Discussion

This descriptive study offers new insight into how UK GPs view placebos. GPs typically defined placebos as treatments that lacked something—active ingredients, adverse or beneficial effects, known mechanism of action and/or scientific evidence. When deciding whether placebos were ethically acceptable, GPs weighed an array of potential benefits (including inducing beneficial placebo effects) and possible harms (including deception and negative side effects) for individual patients, doctor–patient relationships, the NHS and society. Many GPs assumed deception was necessary when prescribing pure placebos, while impure placebos were thought to have more adverse effects than pure placebos. Prioritizing truth-telling seemed to foster a preference for impure over pure placebos, while prioritizing the need to do no harm seemed to foster a preference for pure placebos. While some GPs were adamant in seeing no place for placebos in clinical practice, others had a completely different perspective, seeing placebo effects as ubiquitous in primary care; guidance to assist GPs navigating these interrelated ethical and clinical issues would be very welcomed.

There was evidence of all four fundamental bioethical principles (16) being brought to bear in GPs’ comments on the use of placebos in clinical practice: non-maleficence (placebo prescribing should do no harm), beneficence (weighing benefits and costs, prescribe placebos if they benefit the patient), respect for autonomy (one should not lie or deceive one’s patient) and justice (placebo prescribing uses valuable societal-level resources). Conflict between ethical principles creates dilemmas. In relation to placebos in clinical practice, one dilemma appears to result from assuming that one must lie to a patient to evoke a (pure) placebo effect, which could enhance a patient’s health/alleviate suffering: here there is a conflict between the principles of respect for autonomy and beneficence, which has been discussed in the scientific literature (17). Recent evidence challenges this, suggesting that deception may not always be necessary to elicit beneficial placebo effects in clinical populations (18). Comments that placebos lack any evidence or known mechanisms of action suggested GPs might not be aware of the considerable evidence confirming the existence of significant placebo and nocebo effects and elucidating their physiological and neurological mechanisms of action (19,20).

GPs expressed largely ethical concerns about placebo interventions and requested guidance on acceptable practice around placebos use. While some GPs wanted to harness placebo effects to benefit their patients, many thought deception was necessary and thus viewed placebo prescribing as unacceptable, not wanting to jeopardize doctor–patient relationships built on honesty and trust. Similarly, a study of Swiss GPs also identified a need for ethical guidance around clinical uses of placebos (12). Well-targeted and informed guidance could help to reduce ethical breaches, increase awareness of placebo effects and mechanisms, share good practice and encourage appropriate and patient-centred use of placebo interventions.

A number of limitations in this study are worth noting. Many of the topics that appeared in GPs’ responses to the open-ended questions reflected the closed-ended questionnaire items. This suggests that the closed-ended questionnaire items were tapping into issues that were relevant GPs. It might also suggest that the questionnaire items cued participants to focus narrowly on specific aspects of placebos in the open-ended questions. The comments were themselves often short and there was no way for the researchers to probe individual respondents to elaborate their views. In some cases, this hampered our ability to provide a clear interpretation of the data, for example when it was not clear whether comments related to pure or impure placebos. Another limitation arises from the ubiquitous confusion surrounding the definition of placebos. Contrary to what many respondents appeared to believe, placebos are not (always) inactive. Qualitative interviews would have allowed us to better ‘unpack’ and elucidate the apparent contradiction between defining a substance as inert and then proceeding to describe its effects. Given the misunderstandings that surround placebos and the divergence of opinions and confusion over the definitions, further qualitative work is warranted not only with GPs but also with patients, to provide an essential counter-balance.

Conclusion

This initial descriptive analysis provides preliminary insights into the ways in which GPs think about placebos and their effects. Perceived costs, benefits and ethical barriers to placebo use have been elucidated. Some GPs were adamant that placebos have no role in clinical practice, particularly when they are prescribed deceptively. Other GPs had a very different perspective and thought placebo effects are ubiquitous in primary care. Official guidance to assist GPs navigating these interrelated ethical and clinical issues should distinguish between placebos and placebo effects and would be welcomed.

Declaration

Funding: University of Oxford Department of Primary Care Health Sciences and Southampton Complementary Medical Research Trust.

Ethical approval: University of Oxford.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Acknowledgements

Jeremy Howick is an NIHR SPCR Fellow. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Zhang W, Robertson J, Jones AC, Dieppe PA, Doherty M. The placebo effect and its determinants in osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 1716–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patel SM, Stason WB, Legedza A, et al. The placebo effect in irritable bowel syndrome trials: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2005; 17: 332–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kirsch I, Sapirstein G. Listening to prozac but hearing placebo: a meta-analysis of antidepressant medication. Prev Treatment 1998; 1: Article 0002a. doi:10.1037/1522-3736.1.1.12a. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Colloca L, Miller FG. Harnessing the placebo effect: the need for translational research. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2011; 366: 1922–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tilburt JC, Emanuel EJ, Kaptchuk TJ, Curlin FA, Miller FG. Prescribing ‘placebo treatments’: results of national survey of US internists and rheumatologists. BMJ 2008; 337: a1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meissner K, Höfner L, Fässler M, Linde K. Widespread use of pure and impure placebo interventions by GPs in Germany. Fam Pract 2012; 29: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fässler M, Gnädinger M, Rosemann T, Biller-Andorno N. Use of placebo interventions among Swiss primary care providers. BMC Health Serv Res 2009; 9: 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fässler M, Meissner K, Schneider A, Linde K. Frequency and circumstances of placebo use in clinical practice–a systematic review of empirical studies. BMC Med 2010; 8: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miller FG, Colloca L. Semiotics and the placebo effect. Perspect Biol Med 2010; 53: 509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Comaroff J. A bitter pill to swallow: placebo therapy in general practice. Sociol Rev 1976; 24: 79–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwartz RK, Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Physician motivations for nonscientific drug prescribing. Soc Sci Med 1989; 28: 577–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fent R, Rosemann T, Fässler M, Senn O, Huber CA. The use of pure and impure placebo interventions in primary care - a qualitative approach. BMC Fam Pract 2011; 12: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Howick J, Bishop FL, Heneghan C, Wolstenholme J, Stevens S, Hobbs FDR, Lewith G. Placebo use in the United Kingdom: results from a national survey of primary care practitioners. PLoS One 2013; 8: e58247 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000; 23: 334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Joffe H, Yardley L. Content and thematic analysis. In: Marks DF. (ed). Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology. London, UK: Sage, 2004, pp. 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th edn. Cary, NC: OUP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miller FG, Colloca L. The legitimacy of placebo treatments in clinical practice: evidence and ethics. Am J Bioeth 2009; 9: 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaptchuk TJ, Friedlander E, Kelley JM, et al. Placebos without deception: a randomized controlled trial in irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS One 2010; 5: e15591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benedetti F, Amanzio M. The placebo response: how words and rituals change the patient’s brain. Patient Educ Couns 2011; 84: 413–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Finniss DG, Kaptchuk TJ, Miller F, Benedetti F. Biological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effects. Lancet 2010; 375: 686–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]