1. Main text

Inflammation is a host defense mechanism that protects the body from invading pathogens and has five hallmarks: redness, swelling, heat, pain, and loss of function [1], [2], [3]. Inflammatory responses are initiated by macrophages recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns by pattern recognition receptors expressed on their surfaces and activating inflammatory signaling pathways, such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), activator protein-1 (AP-1), and interferon-regulatory factors (IRFs) [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are the main pattern recognition receptors in macrophages, and TLR4 is a molecular receptor of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the most powerful agonist derived from gram-negative bacteria able to activate inflammatory responses. LPS binding with TLR4 transduces inflammatory signaling cascades by activating various intracellular signaling kinases in macrophages, resulting in the overexpression of inflammatory genes, including inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and the production of inflammatory mediators, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, nitric oxide (NO), and prostaglandin E2 [4], [5], [6], [8], [9].

Ginsenosides are the main active ingredients found in ginsengs and were reported to have many functions, including antiinflammatory, anticancer, antiviral, and antioxidative activities [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Recently, we prepared a new fraction of Korean ginseng containing a high amount of compound K, named BIOGF1K, and demonstrated its antiinflammatory activity [15]. Despite this study reporting an antiinflammatory role of BIOGF1K, mechanisms by which BIOGF1K plays a protective role in inflammatory responses remains unclear. Therefore, in this study, the antiinflammatory activity of BIOGF1K and the underlying mechanism present during inflammatory responses were investigated using an in vitro inflammatory cell model, specifically LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells.

RAW264.7 and HEK293 cells (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), respectively, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco), streptomycin, penicillin, and l-glutamine at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide–humidified incubator. To measure NO amount, RAW264.7 cells pretreated with BIOGF1K (0–30 μg/mL) for 30 minutes were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 hours, and NO amount in culture media was measured by Griess assay [16]. To determine cell viability, RAW264.7 cells were treated with BIOGF1K (0–30 μg/mL) for 24 hours, and cell viability was measured by a conventional 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay [17]. To determine mRNA expression levels, RAW264.7 cells pretreated with BIOGF1K (0–30 μg/mL) for 30 minutes were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 hours and total RNA was extracted using TRI Reagent® solution (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Complementary DNA was synthesized using 1 μg of total RNA using MuLV reverse transcriptase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. mRNA expression levels were measured by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. The nucleic acid sequences of primers are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for semiquantitative RT-PCR in this study

| Name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| iNOS | F | CCCTTCCGAAGTTTCTGGCAGCAG |

| R | GGCTGTCAGAGCCTCGTGGCTTTGG | |

| COX-2 | F | CACTACATCCTGACCCACTT |

| R | ATGCTCCTGCTTGAGTATGT | |

| TNF-α | F | TTGACCTCAGCGCTGAGTTG |

| R | CCTGTAGCCCACGTCGTAGC | |

| GAPDH | F | CACTCACGGCAAATTCAACGGCA |

| R | GACTCCACGACATACTCAGCAC |

COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

To determine an AP-1 activity, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing Flag-MyD88, AP-1-Luc, and β-galactosidase for 24 hours using polyethylenimine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) and treated with BIOGF1K (0–30 μg/mL) for 24 hours. The cells were lysed by repeating freezing and thawing processes three times, and luciferase activities in the cell lysates were measured, as reported previously in a study by Yi et al [18]. To analyze the activities of signaling molecules during inflammatory responses, nuclear fraction and total cell lysates were prepared, and the active forms of signaling molecules were determined by immunoblotting analysis using specific antibodies recognizing phospho-forms of signaling proteins. RAW264.7 cells pretreated with BIOGF1K (30 μg/mL) for 30 minutes were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for the indicated time. HEK293 cells pretreated with BIOGF1K (0–30 μg/mL) for 24 hours were transfected with hemagglutinin (HA)-tumor growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) (0.5 μg/mL) for 48 hours. To prepare total RAW264.7 and HEK293 cell lysates, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco) three times and lysed in an ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 150 mM NaCl) by sonication (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The lysed cells were centrifuged at 15,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatants were transferred to a fresh tube as total cell lysates. A RAW264.7 cell nuclear fraction was prepared, as previously described in a study by Yi et al [19]. For immunoblotting analysis, total cell lysates or nuclear fraction were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Total and phosphorylated forms of c-Jun, c-Fos, activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2), fos-related antigen 1, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, p38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK kinase 1/2 (MEK1/2), MAPK kinase 3/6 (MKK3/6), TAK1, HA, lamin A/C, and β-actin were detected by the antibodies specific for the targets and were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence solution (AbFrontier, Seoul, Korea). The data are presented as a mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed by analysis of variance/Scheffe post hoc test and Kruskal–Wallis/Mann–Whitney U test. A p value < 0.05 was regarded statistically significant. All data were analyzed using an SPSS program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

We first examined the effect of BIOGF1K on NO production, one of the critical inflammatory mediators in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Prednisolone was used as a standard compound because it has been known to downregulate COX-2 and inflammatory cytokines [20]. Like prednisolone, BIOGF1K dose-dependently suppressed NO production in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 1A) without serious cytotoxicity (Fig. 1B), indicating the antiinflammatory activity of BIOGF1K by the reduction of inflammatory mediators without cytotoxicity at the doses studied herein.

Fig. 1.

LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NO, nitric oxide; PRED, prednisolone.

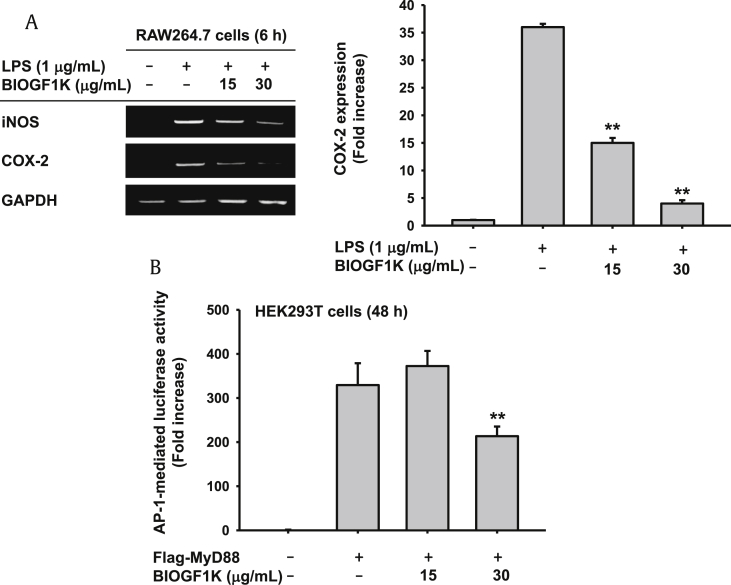

To examine the effect of BIOGF1K on mRNA expression of inflammatory genes, RAW264.7 cells were treated with BIOGF1K and LPS, and mRNA expression of iNOS, COX-2, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha was measured by semiquantitative and real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. BIOGF1K dose-dependently inhibited mRNA expression of iNOS and COX-2 in LPS-treated RAW264.7 (Fig. 2A). Inflammatory gene expression is governed by inflammatory signaling pathways, such as AP-1, NF-κB, and IRF-3 [4], [5], [6], [8], and the regulatory activity of BIOGF1K in NF-κB and IRF-3 signaling pathways have been demonstrated in a previous study by Hossen et al [15]. Therefore, the effect of BIOGF1K on an AP-1 signaling pathway was examined by a luciferase assay. HEK293 cells transfected with plasmids expressing AP-1-Luc and Flag-MyD88, an adaptor molecule able to activate AP-1 signaling, were treated with BIOGF1K. BIOGF1K markedly suppressed the AP-1–mediated luciferase activity (Fig. 2B), suggesting that BIOGF1K downregulates mRNA expression of inflammatory genes by suppressing an AP-1 signaling pathway in macrophages.

Fig. 2.

COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Mechanisms by which BIOGF1K suppresses an AP-1 pathway in macrophage during inflammatory responses was further investigated by use of immunoblotting analysis. The hallmark of transcription factor activation is their nuclear translocation. Therefore, nuclear translocation of AP-1 transcription factors was examined in macrophages. BIOGF1K inhibited nuclear translocation of c-Jun (at 90 minutes), ATF2 (at 90 minutes), and phospho (p)-fos-related antigen 1 (at 60 minutes and 90 minutes) in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3A). The effect of BIOGF1K on the activities of MAPKs in AP-1 signaling was examined. BIOGF1K inhibited the activation of p38 (60 minutes) and ERK (90 minutes) in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3B). Phosphorylation of MAPK kinases (MAPKKs), upstream signaling molecules of MAPKs were further investigated and found that BIOGF1K inhibited the activation of MEK1/2 (30 minutes) and MKK3/6 (30 minutes) in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3C). This result strongly supports the hypothesis of this study, since MEK1/2 and MKK3/6 are known as upstream MAPKKs of ERK and p38, respectively [21], [22]; moreover, BIOGF1K inhibited the activation of MAPKKs earlier (30 minutes) than that of MAPKs (60 minutes) (Fig. 3B, C). These results suggest that BIOGF1K inhibits the AP-1 signaling pathway by inhibiting ERK and p38 MAPKs and MEK1/2 and MKK3/6, the upstream MAPKKs of ERK and p38, in macrophages during inflammatory responses. However, the common upstream molecule of MEK1/2 and MKK3/6, TAK1, was not affected by BIOGF1K. We further confirmed the suppressive effect of BIOGF1K on the activation of these MAPKs and MAPKKs in HEK293 cells by transfecting HA-TAK1, an activator of an AP-1 signaling pathway. As expected, BIOGF1K (30 μg/mL) suppressed the activation of MEK1/2 and ERK (Fig. 3D) and MKK3/6 and p38 (Fig. 3E), respectively, in HA-TAK1-transfected HEK293 cells.

Fig. 3.

ATF2, activating transcription factor 2; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FRA1, fos-related antigen 1; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MEK1/2, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK kinase 1/2; MKK3/6, MAPK kinase 3/6; TAK1, tumor growth factor-β-activated kinase 1.

In this study, we investigated an antiinflammatory activity of BIOGF1K in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. We found that BIOGF1K suppressed the activation of an AP-1 pathway by targeting MAPKs, such as ERK and p38, and MAPKKs, such as MEK1/2 and MKK3/6, as summarized in Fig. 4, thereby suppressing inflammatory gene expression, such as iNOS and COX-2, as well as inflammatory mediator production, such as NO in macrophages during inflammatory response. For further validating inhibitory mechanism of BIOGF1K, whether TAK1 can be directly inhibited by BIOGF1K will be evaluated by employing a kinase assay. Collectively, these results strongly suggest that BIOGF1K, an active ingredient in ginseng, plays a protective role in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses and provides evidence that BIOGF1K should be further examined as a promising antiinflammatory agent to prevent and treat inflammatory diseases.

Fig. 4.

AP-1, activator protein-1; ATF2, activating transcription factor 2; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FRA1, fos-related antigen 1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MEK1/2, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK kinase 1/2; MKK3, MAPK kinase 3; NO, nitric oxide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; TAK1, tumor growth factor-β-activated kinase 1; TLR, toll-like receptors; CD14, cluster of differentiation 14; TRIF, Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein inducing interferon beta.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was also supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2017R1A6A1A03015642), Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2018.02.001.

Contributor Information

Jong-Hoon Kim, Email: jhkim1@jbnu.ac.kr.

Junseong Park, Email: superbody@amorepacific.com.

Jae Youl Cho, Email: jaecho@skku.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Janeway C.A., Jr., Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yi Y.S. Folate receptor-targeted diagnostics and therapeutics for inflammatory diseases. Immune Netw. 2016;16:337–343. doi: 10.4110/in.2016.16.6.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yi Y.S. Caspase-11 non-canonical inflammasome: a critical sensor of intracellular lipopolysaccharide in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Immunology. 2017;152:207–217. doi: 10.1111/imm.12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yi Y.S., Son Y.J., Ryou C., Sung G.H., Kim J.H., Cho J.Y. Functional roles of Syk in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:270302. doi: 10.1155/2014/270302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu T., Yi Y.S., Yang Y., Oh J., Jeong D., Cho J.Y. The pivotal role of TBK1 in inflammatory responses mediated by macrophages. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:979105. doi: 10.1155/2012/979105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byeon S.E., Yi Y.S., Oh J., Yoo B.C., Hong S., Cho J.Y. The role of Src kinase in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:512926. doi: 10.1155/2012/512926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Italiani P., Boraschi D. New insights into tissue macrophages: From their origin to the development of memory. Immune Netw. 2015;15:167–176. doi: 10.4110/in.2015.15.4.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y., Kim S.C., Yu T., Yi Y.S., Rhee M.H., Sung G.H., Yoo B.C., Cho J.Y. Functional roles of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:352371. doi: 10.1155/2014/352371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim K.H., Kim T.S., Lee J.G., Park J.K., Yang M., Kim J.M., Jo E.K., Yuk J.M. Characterization of proinflammatory responses and innate signaling activation in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium scrofulaceum. Immune Netw. 2014;14:307–320. doi: 10.4110/in.2014.14.6.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J.H., Yi Y.S., Kim M.Y., Cho J.Y. Role of ginsenosides, the main active components of Panax ginseng, in inflammatory responses and diseases. J Ginseng Res. 2017;41:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baek K.S., Yi Y.S., Son Y.J., Yoo S., Sung N.Y., Kim Y., Hong S., Aravinthan A., Kim J.H., Cho J.Y. In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activities of Korean Red Ginseng-derived components. J Ginseng Res. 2016;40:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J., Yuan D., Xing T., Su H., Zhang S., Wen J., Bai Q., Dang D. Ginsenoside Rh2 inhibiting HCT116 colon cancer cell proliferation through blocking PDZ-binding kinase/T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase. J Ginseng Res. 2016;40:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee M.H., Lee B.H., Jung J.Y., Cheon D.S., Kim K.T., Choi C. Antiviral effect of Korean red ginseng extract and ginsenosides on murine norovirus and feline calicivirus as surrogates for human norovirus. J Ginseng Res. 2011;35:429–435. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2011.35.4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aravinthan A., Kim J.H., Antonisamy P., Kang C.W., Choi J., Kim N.S. Ginseng total saponin attenuates myocardial injury via anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties. J Ginseng Res. 2015;39:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hossen M.J., Hong Y.D., Baek K.S., Yoo S., Hong Y.H., Kim J.H., Lee J.O., Kim D., Park J., Cho J.Y. In vitro antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of the compound K-rich fraction BIOGF1K, prepared from Panax ginseng. J Ginseng Res. 2017;41:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho J.Y., Baik K.U., Jung J.H., Park M.H. In vitro anti-inflammatory effects of cynaropicrin, a sesquiterpene lactone, from Saussurea lappa. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;398:399–407. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi Y.S., Cho J.Y., Kim D. Cerbera manghas methanol extract exerts anti-inflammatory activity by targeting c-Jun N-terminal kinase in the AP-1 pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;193:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yi Y.S., Baek K.S., Cho J.Y. L1 cell adhesion molecule induces melanoma cell motility by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Pharmazie. 2014;69:461–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghidini E., Capelli A.M., Carnini C., Cenacchi V., Marchini G., Virdis A., Italia A., Facchinetti F. Discovery of a novel isoxazoline derivative of prednisolone endowed with a robust anti-inflammatory profile and suitable for topical pulmonary administration. Steroids. 2015;95:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cargnello M., Roux P.P. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011;75:50–83. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00031-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roux P.P., Blenis J. ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases: a family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:320–344. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.320-344.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.