Abstract

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is responsible for 1–2% of all strokes in adults. Venous occlusive disease is a less common condition than the arterial one, but probably underestimated in the past [1]. Its early detection is crucial to ensure appropriate therapy, to prevent irreversible brain injury. The neuroradiological study is crucial to formulate the diagnosis.

Unenhanced computed tomography (CT) is usually the first imaging study performed on an emergency basis.

We report the case of a woman who present a migrant headache, resistant to the therapy. It was at first performed an axial CT scan of the brain that was negative.

Afterwards the Patient did an MRI which proves the presence of a hyperintensity rhyme, localized in the left temporal region, in the subdural space, diagnosed like a subdural hemorrhage.

Considering the type and increase of headache, neurologist suggest to perform a venography PC sequence that finally demonstrate the correct diagnosis of a filling defect of left spheno-parietal sinus.

Keywords: Cerebral venous thrombosis, Subdural hemorrhage, MRI

1. Introduction

It is estimated that the annual incidence of cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is between 2 and 7 cases per million [2]. The incidence is likely underestimated as sensitivity for detection of this disease has improved significantly only in recent years. With the advance of MRI, this complex condition has become increasingly recognized in recent years (2) but can still represent a diagnostic dilemma because of its variable, nonspecific clinical manifestations and subtle appearance on traditional imaging modalities.

There are a wide variety of known risk factors, which include thrombophilia, oralcontraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, pregnancy,postpartum, haemoconcentration, infection, trauma,brain surgery, neoplastic invasion or hypercoagulable states. It is well established that CVT preferentially affects women (by a ratio of approximately 3–1).

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is responsible for 1–2% of all strokes in adults. Venous occlusive disease is a less common condition than the arterial one, but its frequency could have been underestimated in the past.

Early detection of venous occlusion is of crucial importance as timely introduction of an appropriate therapy may prevent irreversible brain injury. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is predominant in women, for which one of the main risk factors is represented by the use of estro −progestinics. The persistence of an occlusion causes an increase in venous and capillary pressure and reduction in blood pressure resulting in cytotoxic edema and cell death. The increased pressure in capillary vessels can also determinate a blood infarction.

The superior sagittal sinus (70–80%), transverse sinuses and sigmoid sinuses (70%) are themost commonly affected dural sinuses, while the cavernous sinus and straight sinus are less frequently involved [2]. The clinical presentation of venous occlusive disease may be subtle

and polymorphous. In about half of the cases the onset of clinical symptomsissubacute, i.e. occurs 2–30 days after the event start and is associated with a slow progression of the thrombus and the establishment of collateral outflow circles; It is rarer than the acute onset (<2 days, 30%) and chronic (more than a month, 20%).

The most common presenting initial OR associated symptom is a persistent, severe, progressive and unilateral headache. Thesymptoms may also include focal neurological signs (aphasia, hemiplegia, amnesia, hemianopia, etc.) and epileptic seizures. The neuroradiologicalassessment is crucial for formulating the correct the diagnosis. Both CT and MRI are able to show both the direct and the indirect signs of thrombosis. Angio-CT and MRA allow the demonstration confirmation and recognition of the occlusion of the venous sinuses.

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is responsible for 1–2% of all strokes in adults [1]. The true incidence of this disease is unknown, although the widespread use of magnetic resonance imaging has certainly increased the frequency of its recognition [3].

2. Case report (clinical findings)

A 38year-old female presented to emergency department (ED) with headache resistant to medical therapyfor more than a week. Her medical andfamily history was unremarkable.

She had regular menstrual periods, no past history of migraine and didn’t use estro-progestinics or other chronic treatments.

No remarkable abnormalities were found on complete physical andneurological examination.

Blood tests revealed the presence of mild anemia (hemoglobin 89 g/L, normal range 110–150 g/L) and slightly elevated platelet counts (457 × 109/L, normal range, 140–450 × 109/L). Her white blood cell counts were within normal ranges. Her level of C-reactive protein was slightly increased to 15 mg/L (normal range, 0–10 mg/L).

The patient was evaluated by a neurologist and underwent an unenhanced CT brain scan in emergency and an elected MRI in hospitalization.

3. Imaging findings

The unenhanced CT scan showed the absence of any haematichhyperdensity and no focal tomodensitometric alterations of pathologic significance in brain tissue. The ventricular system was normal and in axis on the midline. The subarachnoid spaces were within the limits [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1.

Axial unhenhanced CT scan: absence of any haematich hyperdensity and no focal tomodensitometric alterations of pathologic significance in braintissue.

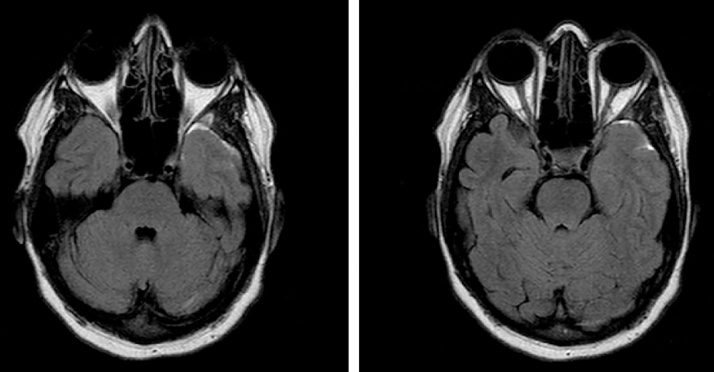

The patient was hospitalized and underwent MRI which showed the presence of a linear signal hyperintensity in T1 and T2 FLAIR weighted images localized around the tip of the temporal lobe [Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4].

Fig. 2.

TOF-RM: Hyperintensity localized around the tip of the temporal lobe.

Fig. 3.

T1 Sequences: Hyperintensity localized around the tip of the temporal lobe.

Fig. 4.

T2 FLAIR Sequences: Hyperintensity localized around the tip of the temporal lobe.

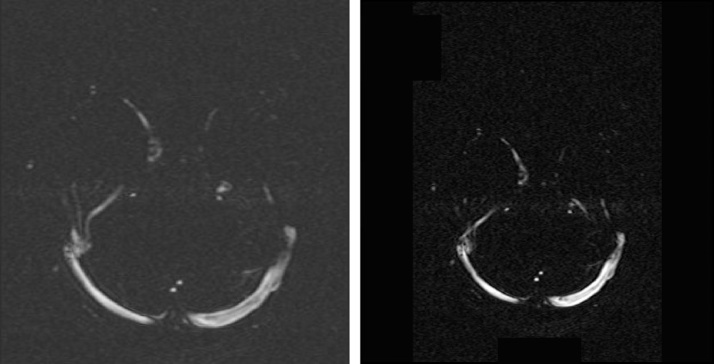

Subsequent gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) venography demostrate a filling defect of left spheno-parietal sinus [Fig. 5].

Fig. 5.

RM Venography: a filling defect of left spheno-parietal sinus.

4. Discussion

Cerebral venous thrombosis is a rare and potentially life-threatening pathology. It is an emergency that requires a rapid introduction of anticoagulant treatment, but whose diagnosis can be challenging. The range of clinical symptoms and the variability of MRI or CT findings may explain the diagnostic challenges and certain errors.

Our case concerned a female patient, who presented to the emergency department with a headache. The initial diagnostic framework included neurological consultation and an unhenanced CT brain scan, which were both negative. The CT scan showed no focal densitometric alterations of pathologic significance in brain tissue.

Based on the unenhanced MRI finding diagnostic hypothesis of subdural hemorrhage sine material was raised. Only after the execution of enhanced MRI using venography PC sequence, the diagnosis of venous thrombosis of the left spheno-parietal sinus could be made and a proper therapy was undertaken.

Unenhanced CT is usually the first imaging study performed on an emergency basis for headaches and suspected brain vascular events. Unenhanced CT allows detection of ischemic changes related to venous insufficiency and sometimes demonstrates a hyperattenuating thrombosed dural sinus or vein [4].

Onnon-enhanced brain CT, cerebral venous thrombosis may onlybe considered indirectly while physicians trace a hyper-densityband along cerebral venous system (ref)

A direct sign of thrombosis on enhanced CT is the “empty delta sign” (filling defect in a cerebral vein due to the thrombus), reported in a third of patients. Indirect, but non-specific signs are more frequent and include: cerebral edema, collateral venous drainage, haemorrage or venous infarct. However, in 25–30% of patients CT is normal.

Sometimes, brain MRIimaging with venography is needed to confirm the diagnosis of CVT.

Venous thrombosis can be detected with direct visualization of parenchymal images on MRI, CT or with various venographic techniques. The most commonly used venographic techniques currently include unenhanced TOF MRI venography, contrast-enhanced MRI venography, and CT venography. Phase contrast MRI venography is less often used, because of its dependence on operator- defined velocity encoding parameters [1].

Contrast-enhanced MRI venography with elliptic centric ordering is a more recently developed venographic method in which the paramagnetic effect of intravenous gadolinium is used to shorten T1 and provide positive intravascular contrast enhancement [5]. MRIvenography provides high-quality images of the intra- cranial venous anatomy. Small-vessel visualization is improved at contrast-enhanced MR venography, compared with that at TOF MR venography [5].

The superficial middle cerebral vein (SMCV) (also known as the Sylvian vein) is one of the superficial cerebral veins. It usually passes along the Sylvian fissureposteroanteriorly, it collects numerous small tubutaries which drain the opercular areas around the lateral sulcus. It curves anteriorly around the tip of the temporal lobe and drains into the sphenoparietal sinus or cavernous sinus. However, there is significant individual variation [5].

It should be highlighted that there are no clinical algorithms or specific laboratory tests that can guide the identification of CVT and, therefore, the diagnosis relies exclusively on imaging tests. As CVT may have a poor short and long-term prognosis, making a timely diagnosis and early anticoagulant treatment two cornerstones in the clinical management of these diseases.

The clinical symptoms of the patient were subtle and not specific, she complained just about headache resistant to medical therapy for more than 7 days.

The clinical manifestations of cerebral venous thrombosis vary, depending on the extent, localization, and acuity of the venous thrombotic process, as well as the adequacy of venous collateral circulation. Headache is experienced by 75%–95% of patients with CVT but the features are not specific and may mimic other headache syndromes, such as migraine or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Headaches may be gradual in onset or acute, localized, or diffuse. Headache associated with CVT may be seen in isolation or with additional symptoms of intracranial hypertension, such as vomiting and visual disturbance. In addition to these symptoms, patients may develop focal neurologic deficits seizures, and changes in mental status.

In conclusion, keeping the cerebral venous thrombosis in mind is important for physicians to approach a patient with headache admitted to ED. Accurate and prompt diagnosis of cerebral venous thrombosis is crucial, because timely and appropriate therapy can reverse the disease process and significantly reduce the risk of acute complications and long- term sequelae. Our patient started anticoagulation therapy (including subcutaneous LMWH) on the same day of the CVT diagnosis by MRI venography PC and could be discharged smoothly from the hospital after 10 days.

Authors declaration

-

1.

We the undersigned declare that this manuscript is original, has not been published before and is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

-

2.

We wish to draw the attention of the Editor to the following facts which may be considered as potential conflicts of interest and to significant financial contributions to this work. [OR]

-

3.

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome. We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors.

-

4.

We further confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved either experimental animals or human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript

Contributor Information

E. Di Caprera, Email: elena.dicaprera@virgilio.it.

L. De Corato, Email: laura.decorato@icloud.com.

V. Giuricin, Email: evaluna_84@hotmail.it.

M.C. Pensabene, Email: claudiapensabene89@gmail.com.

M. Melis, Email: milenamelis@tiscali.it.

F. Garaci, Email: garaci@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Leach James L., Fortuna Robert B., Jones Blaise V., Gaskill-Shipley Mary F. Imaging of cerebral venous thrombosis: current techniques, spectrum of findings, and diagnostic pitfalls. RSNA Radiogiogr. 2017 doi: 10.1148/rg.26si055174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renowden Shelley. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Eur. Radiol. 2004 doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodallec M.H., Krainik A., Feydy A., Hélias A., Colombani J.M., Jullès M.C., Marteau V., Zins M. Cerebral venous thrombosis and multidetector CT angiography: tips and tricks. Radiographics. 2006 Oct doi: 10.1148/rg.26si065505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki Yasuhiro, Matsumoto Kiyoshi. Variations of the superficial middle cerebral vein: classification using three-dimensional CT angiography. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2000;938(May):2000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farb R.I., Scott J.N., Willinsky R.A., Montanera W.J., Wright G.A., terBrugge K.G. Intracranial venous system: gadolinium-enhanced three-dimensional MR venography with auto-triggered elliptic centric-ordered sequence initial experience. Radiology. 2003;226(1):203–209. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2261020670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]