Abstract

Objectives

A lifecourse framework was used to examine the association between major and everyday measures of perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among African American men and to evaluate whether these relationships differed for young, middle-aged, and older men.

Method

The association between both major and everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms, as measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale, was assessed among 296 African American men in the 2011–2014 Nashville Stress and Health Study (NSAHS) using ordinary least squares regression. Interactive associations between major and everyday discrimination and age patterns in the discrimination–depressive symptoms relationship were also investigated.

Results

Everyday, but not major discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms among African American men. This relationship was stronger among middle-aged men and diminished among older men. However, major discrimination, but not everyday discrimination, was associated with depressive symptoms of older men (age 55+), with greatest depressive symptomatology among those reporting both forms of discrimination.

Discussion

Everyday discrimination is a more consistent predictor, relative to major discrimination, of depressive symptoms among African American men across the lifecourse, although there were age and/or cohort differences. Findings also demonstrate the synergistic, or additive, impact of multiple forms of discrimination on mental health.

Keywords: African American, Depression, Discrimination, Health disparities, Lifecourse, Men, Minority and diverse populations, Psychosocial factors

Depression is one of the most prevalent mental health conditions among adults of all ages and is a well-established risk factor for many adverse outcomes in physical health (Clarke & Currie, 2009) and other important life domains. For instance, depression has been linked to higher mortality (Cuijpers & Smit, 2002), poorer physical health (Hammond, 2012), and greater use of health care services (Simon, Ormel, VonKorff & Barlow, 1995). While a large body of literature has examined the antecedents and consequences of depression, it is critical to note that the risk factors associated with depression, and its cascade of consequences, are poorly understood among African American men (Watkins, Green, Rivers, & Rowell, 2006).

In thinking about factors that may be particularly relevant to depression among African American men, it seems critical to examine the role of discrimination. Numerous studies have found an association between discrimination and poor mental health across racial and ethnic groups (for reviews see Krieger, 1999; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Williams, Neighbors & Jackson, 2003); yet, most do not focus on men or on African American men more specifically. Moreover, the studies of depression that have focused on African Americans are equivocal, in some cases finding that the association between discrimination and depression was actually weaker or not statistically significant for African Americans as compared to Whites (Ayalon & Gum, 2011; Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). While several studies reported that older Blacks, and particularly older black men, have more depressive symptoms than older Whites, they did not explore the role of discrimination (Jang, Borenstein, Chiriboga, & Mortimer, 2005; Skarupski et al., 2005).

There is a clear need for research examining linkages between discrimination and depression specifically among African American men. According to a recent review of depression among African American men, Ward and Mengesha (2013) lament that in the past 25 years (1984–2009), only 120 of the studies of depression considered African Americans and, of those, only 19 empirically assessed depression among African American men. In fact, two research teams (Ward & Mengesha, 2013; Watkins et al., 2006) have identified three major, and likely interrelated, psychosocial factors associated with depression among African American men: socioeconomic status (SES), insufficient access to psychosocial coping resources, and, as hypothesized here, racism and discrimination.

It is widely recognized in the scientific literature and, perhaps to a lesser degree, in larger society that African American men face critical disadvantages in nearly every arena of life vis-a-vis White men. African American men are far more likely than White men to live in poverty, to live in neighborhoods with more crime and fewer resources, to be victims of homicide, and to have poor access to medical care. Illustratively, African American men have the shortest life expectancy of any group in America (Kochanek, Murphy & Xu, 2015). Despite recent gains toward income equality, African American men remain at a stark disadvantage in terms of wealth. For instance, a sobering study conducted in 2016 found that it would take 228 years for African American households to attain the same wealth that White households have today (Asante-Muhammed, Collins, Hoxie & Nieves, 2016). In many ways related to these stark material differences, African American men carry a greater burden of social stressors—including discrimination, which occurs both interpersonally and structurally and can also become internalized (Jones, 2000).

African Americans are especially likely to experience discrimination due to racial minority status and the historical legacy of slavery, as well as continued racial injustice in the United States. African American men, more specifically, face a number of distinct psychosocial risk factors that are linked to their social positions as both men and African Americans. In thinking about the effects of discrimination on the health of older African American men, it is necessary to consider discrimination from a lifecourse perspective, which captures both historical and contemporary dimensions of discrimination. As a group, African American men have endured unique barriers to achieving socioeconomic success and good health due to their exposure to institutional and interpersonal racism in the United States (Hargrove & Brown, 2015). For example, Jim Crow laws were not abolished in the south until 1965. Therefore, an African American male who was 70 years old in 2015 would have spent his childhood and adolescence in an era where there were few legal protections for African Americans. In contrast, an African American male who was 50 years old in 2015 would have been born the same year that Jim Crow laws were overturned.

In light of such considerations, we expect that there are cohort differences in the relationship between discrimination and the likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms among African American men. Although prior research suggests that children and adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to discrimination and its cascade of negative consequences (Priest et al., 2013), few studies have addressed potential age and cohort differences in the discrimination–health association. The present study addresses two critical needs at once: (a) the need for better understanding of depression and its antecedents among African American men and (b) examination of the role of the lifecourse—in this case, the adult lifecourse (i.e., young adulthood, middle age, and older adulthood)—in shaping the link between discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American men.

A growing body of literature on perceived discrimination and its health consequences has distinguished between “everyday” and “major” measures of discrimination (Williams et al., 1997). Whereas everyday discrimination focuses on chronic, interpersonal slights, hassles, and insults—such as being followed around stores or receiving poor service (Mouzon, Taylor, Woodward, & Chatters, 2016)—experiences of major discrimination are those that encompass singular, discrete incidents of unfair treatment in macro areas of society, such as the labor market, the criminal justice system, lending practices, and the housing market, which have major implications for livelihood, success, and upward mobility ( Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams 1997; Mouzon et al., 2016). Among men, the stress of experiencing both everyday and major discrimination may be compounded by the stress of having their gender identity called into question or challenged or by the inability to carry out responsibilities that are culturally regarded as part of being a man, including being able to financially provide for their families (Williams et al., 2003). Furthermore, because experiences with major discrimination can impede one’s socioeconomic progress and success, it is possible that this form of perceived discrimination is especially detrimental for the health and well-being of African American men (Hargrove & Brown, 2015).

The Lifecourse, Discrimination, and Depression among African American Men

Although there have been a few recent studies examining the relationship between discrimination and depression, the mechanisms linking discrimination and depression in African American men are unclear. Several issues have limited our understanding. First, most studies have focused on the relationship between discrimination and depression among particular age groups, including adolescence (Watkins, Hudson, Caldwell, Siefert, & Jackson, 2011). However, there is a need to examine these processes across the lifespan, as prevalence of depression tends to be highest among middle-aged adults. In addition, the mental health toll of experiences with discrimination is likely cumulative. Nevertheless, there is evidence that African Americans engage in behavioral coping strategies that can be protective against depression and other mental health consequences of lower social status and related experiences of discrimination (Abdou, 2013; Abdou et al., 2013; Abdou et al., 2010; Mezuk et al. 2010, 2013; Mouzon, Taylor, Woodward, & Chatters, 2016). It is important to note, however, that these studies were not focused on men and that there are likely gendered dimensions of discrimination (Williams et al., 2003; Ifatunji & Harnois, 2016) that impact mental health among African American men across the lifecourse. In sum, additional research that examines the discrimination–depression relationship among men across young, middle, and older adulthood is needed.

The few studies that have examined links between discrimination and depression among African American men have most commonly examined the role of everyday discrimination only (Watkins et al., 2011). Everyday discrimination focuses on chronic, everyday slights that are often painful, such as being treated unfairly in public settings, whereas major discrimination captures more discrete events, which often focus on perceptions of SES-based factors (e.g., being fiscally responsible and worthy of renting an apartment or obtaining a mortgage).

Given their different dimensions, we argue that it is important to examine both everyday and major discrimination in assessing the perceived discrimination–depression link among African American men across the adult lifecourse (Hudson et al., 2012). African American men face both systemic racism (Williams et al., 2003) and interpersonal discrimination (Hudson, Puterman, Bibbins-Domingo, Matthews, & Adler, 2013; Lincoln, Taylor, Watkins, & Chatters, 2010; Watkins et al., 2011). It is, therefore, likely important to assess the independent and synergistic contributions of systemic and interpersonal racism to the experience of depressive symptoms across the lifecourse as an African American man. It is possible that the effects of everyday and major discrimination are cumulative and that experiencing one form of discrimination influences the mental health consequences of experiencing the other (Lewis, Cogburn, & Williams, 2015).

Research Aims

The goals of this study were threefold:

(i) To examine the associations between major and everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms, assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale, among African American men.

(ii) To assess the degree to which the two common measures of discrimination, everyday and major discrimination, vary in their impact on depressive symptoms among African American men.

(iii) To evaluate whether the relationships between discrimination and depressive symptoms among African American men is conditional on age—that is, does the direction and/or magnitude of the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms depend on lifecourse stage (i.e., young adult, middle-aged, or older adult) for African American men?

METHODS

Sample

The Nashville Stress and Health Study (NSAHS) is an epidemiologic community study of African Americans and Whites conducted between 2011 and 2014 in Nashville, Tennessee and the surrounding metropolitan area. This study includes a relatively large sample of African American men of diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, and assesses a range of psychosocial factors, including the full CES-D scale. Another strength of the NSAHS is that African American study participants were matched to African American interviewers. A random sample of African American and White men and women was obtained through multistage, stratified sampling. African American households were oversampled to achieve near equal numbers by sex and race. A total of 1,252 respondents completed the survey administered during 3-h computer-assisted, in-person interviews. Of the 1,252 study participants, 296 were African American men. A sampling weight was constructed to account for the complex survey design and to ensure generalizability to the county level. All study procedures have been described in detail elsewhere (Brown, Turner, & Moore, 2016; Turner, Thomas, & Brown, 2016). The Nashville Stress and Health Study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board, and all respondents provided informed consent. The present analysis is limited to the 296 African American men for whom complete data on variables examined in the present study are available. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the sample.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics of African American Men, Nashville Stress and Health Study (2011–2014)

| N | Full sample | Young men | Middle-aged men | Older men |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 296 | 85 | 120 | 92 | |

| Depressive symptoms (0–41) | 12.27 (0.66) | 11.84 (1.02) | 13.89 (1.36) | 10.04 (0.57) |

| Major discrimination | ||||

| Low (Ref.) | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.61 |

| Moderate | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.12* |

| High | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.27 |

| Everyday discrimination | ||||

| Low (Ref.) | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.39 |

| Moderate | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| High | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.11** |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married (Ref.) | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.51*** | 0.55*** |

| Never married | 0.33 | 0.56 | 0.27*** | 0.03*** |

| Other | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.22*** | 0.42*** |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school (Ref.) | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.26 |

| High school graduate | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.30 |

| Some college | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.27* | 0.32* |

| College graduate or higher | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.11*** | 0.12* |

| Occupational prestige (0–100) | 40.89 (1.81) | 45.70 (2.89) | 40.26 (2.22) | 33.26 (2.41)*** |

Note: Weighted means and proportions are presented; standard errors are in parentheses; variable ranges are in brackets; Ref. = Referent category.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 significant age differences; "Young Men" are the referent category.

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured by the CES-D scale (Radloff, 1977). The NSAHS uses a 20-item modified version that asked respondents how often in the past month they felt symptoms relevant to feelings of depression such as, “you were bothered by things that usually don’t bother you,” “you felt that everything you did was an effort,” “you felt sad.” Responses ranged from not at all (coded 0) to almost all the time (coded 4). Items were summed to create continuous CES-D scores ranging from 0 to 54, with higher scores denoting greater depressive symptoms. The scale has high reliability among this sample (α = 0.92).

Discrimination

Exposure to discriminatory experiences was assessed by two measures of discrimination: major and day-to-day or “everyday” discrimination (Kessler et al., 1997). We specifically examined unattributed discrimination, rather than discrimination attributed to race or other factors. Major discrimination is a count of 9 life-time discrimination events, which assesses lifetime exposure to discrimination in domains such as job promotion, housing, and financial institutions. Respondents were asked whether they experienced each event (e.g., “been unfairly fired or denied a promotion,” “for unfair reasons, not been hired for a job”). Items were summed and higher values were indicative of greater discrimination exposure. Everyday discrimination was measured with a nine-item scale (α = 0.84) that assessed the frequency of exposure to slights and hassles such as, “treated with less courtesy than other people” or “people act as if they are afraid of you.” Responses ranged from 0 to 4 (never to almost always). Items were summed, and higher values corresponded with greater discrimination exposure. Both major and everyday discrimination scores were grouped based on the 25th and 75th percentiles in order to form three categories: low, moderate, and high discrimination.

Age was measured categorically: (a) under 40 years (“young men”), (b) 40–54 years (“middle-aged men”), and (c) 55 years and older (“older men”). Respondents’ current marital status was also assessed categorically: (a) married, (b) never married, or (c) other (i.e., separated, widowed, or divorced).

Level of education was measured by asking respondents their highest level of education completed: (a) less than high school, (b) completed high school/GED, (c) some college, and (d) college graduate or higher. Respondents also provided information about the annual income for their household.

Occupational prestige describes individuals’ social class standing based on the perceived prestige of their job position. The NSAHS asked respondents to report their current or last (for retired or recently unemployed individuals) job position and assigned prestige scores between 0 and 100 based on the Nam-Boyd occupational status scale (see Turner, Thomas, & Brown 2016). Higher scores correspond with higher levels of occupational prestige.

Data Analytic Strategy

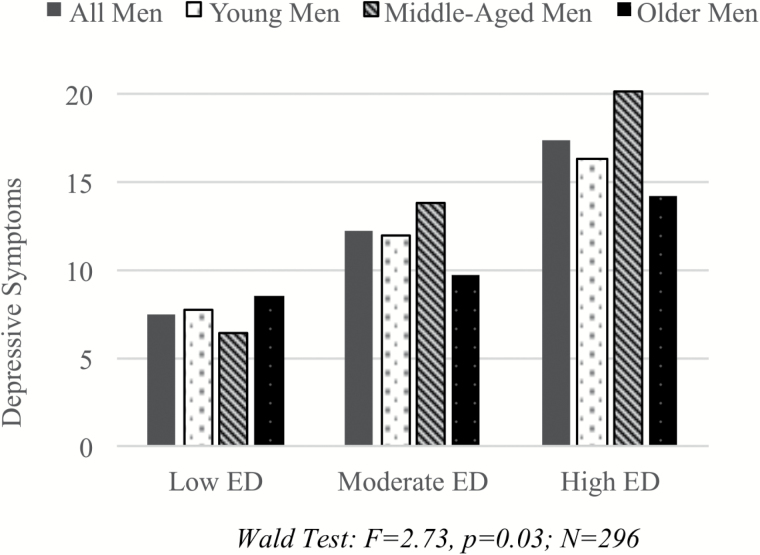

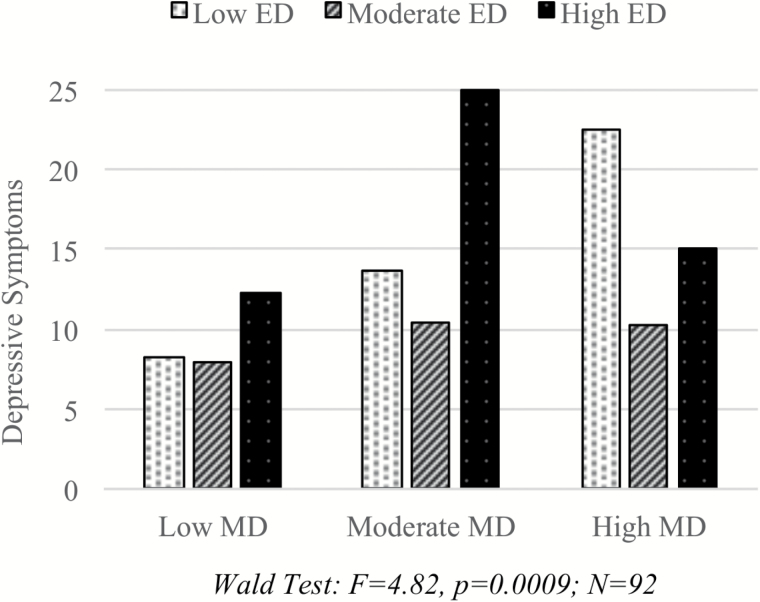

We used a three-step analytic approach to address our research aims. First, we examined the weighted means and proportions of study variables among African American men across age categories (i.e., young, middle-aged, older). T-tests and chi-square significance tests were used to evaluate significant differences in sample characteristics across age groups (see Table 1). Second, we estimated ordinary least squares (OLS) regression coefficients for the full sample, showing the relationships between discrimination and depressive symptoms with a stepwise approach (see Table 2). In Model 1, the relationship between major discrimination and depressive symptoms was examined. Model 2 considered the association between everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms. Both major and everyday forms of discrimination were evaluated in Model 3. All models included age, marital status, education, and occupational prestige as covariates. This approach allows us to examine whether major and everyday measures of discrimination represent independent dimensions. If both dimensions remain significant in the final model (Model 3), there would be evidence that each measure accounts for a distinct portion of the variation in depressive symptoms among African American men. The following interactions were also tested: (a) major discrimination × age, (b) everyday discrimination × age, (c) major discrimination × everyday discrimination. All sociodemographic variables were included as covariates and each interaction was tested individually. Wald tests evaluated statistical significance across levels of the categorical variables, and significant interactions were graphed (see Figure 1). In the third and final step of our analysis, we further examined age differences in these relationships by regressing depressive symptoms on both forms of discrimination for each age group separately (see Table 3). We also tested the major discrimination × everyday discrimination interaction among each age group to consider the potentially synergistic influence of both types of discrimination on depressive symptoms across the life course. All sociodemographic variables were included as covariates, and interactions were tested individually. Wald tests were used to determine statistical significance, and significant interactions were graphed (see Figure 2).

Table 2.

Depressive Symptoms Regressed on Major and Everyday Discrimination among African American Men, Nashville Stress and Health Study (2011–2014; N = 296)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major discrimination | |||

| Low (Ref.) | |||

| Moderate | 1.09 (1.90) | 0.61 (1.80) | |

| High | 2.66 (1.66) | 0.35 (1.80) | |

| Everyday discrimination | |||

| Low (Ref.) | |||

| Moderate | 4.57 (1.48)** | 4.43 (1.83)** | |

| High | 9.93 (1.66)*** | 9.94 (1.42)*** | |

| Age | |||

| Young (under 40 years; Ref.) | |||

| Middle-aged (40–54 years) | 0.24 (1.73) | 1.32 (1.28) | 1.27 (1.44) |

| Older (55+ years) | −3.27 (1.30)** | −1.16 (1.32) | −1.13 (1.30) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married (Ref.) | |||

| Never married | −0.33 (1.63) | −0.43 (1.35) | −0.52 (1.29) |

| Other | −0.32 (2.39) | −0.80 (2.24) | −0.87 (2.15) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school (Ref.) | |||

| High school graduate | −2.62 (2.17) | −1.95 (2.33) | −1.96 (2.37) |

| Some college | −2.05 (1.21) | −2.22 (1.02)* | −2.17 (1.09)* |

| College graduate or higher | −6.04 (1.41)*** | −4.94 (1.75)** | −5.02 (1.62)** |

| Occupational prestige | −0.03 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.03) |

| Intercept | 15.62 (1.85)*** | 10.71 (1.39)*** | 10.67 (1.45)*** |

| F | 5.87*** | 11.07*** | 11.04*** |

| R 2 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

Note: Ref. = referent category; standard errors are included in parentheses.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Figure 1.

Age moderates the relationship between everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms among African American men, Nashville Stress, and Health Study (2011–2014).

Table 3.

Depressive Symptoms Regressed on Major and Everyday Discrimination among African American Men by Age, Nashville Stress and Health Study (2011–2014)

| Young men (under 40) | Middle-aged men (40–54) | Older men (55+) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major discrimination | |||

| Low (Ref.) | |||

| Moderate | 0.08 (1.10) | −0.53 (3.31) | 5.20 (1.94)** |

| High | −2.91 (2.09) | −1.28 (1.74) | 4.54 (1.86)** |

| Everyday discrimination | |||

| Low (Ref.) | |||

| Moderate | 5.63 (2.51)* | 5.84 (2.45)** | −2.65 (1.63) |

| High | 7.97 (0.98)*** | 12.82 (3.30)*** | 3.49 (2.53) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married (Ref.) | |||

| Never married | −0.57 (1.37) | −3.36 (1.70)* | 4.36 (2.54) |

| Other | −2.34 (1.78) | −2.64 (2.17) | 3.19 (2.51) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school (Ref.) | |||

| High school graduate | −5.11 (2.61) | −3.97 (2.11) | 4.11 (2.28) |

| Some college | 0.32 (2.46) | −5.00 (1.63)** | 3.14 (2.25) |

| College graduate or higher | −2.25 (3.04) | −8.59 (1.56)*** | 3.70 (2.38) |

| Occupational prestige | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.06 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.05) |

| Intercept | 10.29** | 16.02 (3.52)*** | 4.44 (2.29)* |

| N | 85 | 120 | 92 |

| F | 28.85*** | 17.12*** | 4.21*** |

| R 2 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.25 |

Note: Ref. = referent category; standard errors are included in parentheses.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Figure 2.

Everyday discrimination moderates the relationship between major discrimination and depressive symptoms among older African American men, Nashville Stress, and Health Study (2011–2014).

Results

Descriptive results for the sample are shown in Table 1. African American men in the NSAHS were diverse across sociodemographic characteristics. Specifically, 39% were between 18 and 39 years, 40% were 40–54 years, and 21% were 55+. Nearly half of the men were married (46%), with younger men were more likely than middle-aged or older men to be single (i.e., never married). In addition, 21% had less than a high school education, 26% had a high school diploma or GED, 32% had some college, and 21% had a college degree or more. Average occupational prestige was 41. Older age groups had less education and lower occupational prestige.

Generally, depressive symptoms were relatively low and consistent across age. The prevalence of discrimination was also similar across groups. For major discrimination, 45% reported low exposure, 24% reported moderate exposure, and 31% reported high exposure.

There was some variation across age groups; however, the only statistically significant difference was that there were significantly fewer older men who reported moderate exposure to major instances of discrimination. These individuals were more likely to report low exposure. For everyday discrimination, most men (48%) reported moderate, rather than low or high, exposure. High everyday discrimination was significantly less prevalent among older African American men (11%) compared with younger African American men (31%).

Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms

Table 2 shows OLS regression models of major and everyday forms of discrimination as predictors of CES-D scores among the full sample. Model 1 indicates that there were no significant differences in depressive symptoms across low, moderate, and high levels of major discrimination. Approximately 11% of the variation in depressive symptoms were explained in Model 1. Relative to low levels, moderate and high everyday discrimination were significantly associated with greater depressive symptoms in Model 2. Men reporting moderate levels of everyday discrimination had depressive symptom scores that were 4.57 points higher. Further, those reporting high levels of everyday discrimination had depressive symptom scores that were 9.93 points higher. This model accounted for 27% of the variation in depressive symptoms. In Model 3, both discrimination forms were considered, and only everyday discrimination was a significant predictor of depressive symptoms. The full model also explained 27% of depressive symptoms among African American men.

Interactions between each discrimination measure and age were tested. There were no significant age differences in the major discrimination–depressive symptoms association. However, the influence of everyday discrimination on symptoms did vary significantly across age (Wald test: F = 2.73; p = 0.03). As shown in Figure 1, the impact of moderate and high everyday discrimination was greatest among middle-aged men. Older men had the lowest symptom levels with exposure to moderate and high everyday discrimination. There interaction between major and everyday discrimination was tested, but this relationship was not significant in terms of predicting depressive symptoms.

Table 3 shows OLS regression models of the discrimination–depressive symptoms association stratified by age. Each model examines major and everyday discrimination simultaneously. Everyday discrimination, but not major discrimination, was associated with greater depressive symptoms among young and middle-aged men. Each model explained 37% of depressive symptoms for young and middle-aged men. Among older men, only major discrimination predicts elevated symptoms with both forms considered. Supplemental analyses (not shown) indicated that both major and everyday discrimination were associated with the depressive symptoms of older men when considered individually. However, once both are included in the model, only major discrimination remained significant. This model explained 25% of the variation in depressive symptoms for older men. In addition, interactions between major and everyday forms of discrimination were tested among each age group. Major discrimination × everyday discrimination was only significant among older men (Wald Test: F=4.82; p = 0.009). Figure 2 shows that for older men who reported low or moderate major discrimination, exposure to high everyday discrimination was associated with significantly higher depressive symptoms. However, older men who reported high major discrimination and low everyday discrimination also had elevated symptoms. Taken together, these models indicate distinct patterns in the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms by age among African American men. They also demonstrate the synergistic impact of major and everyday forms of discrimination on symptoms for older men.

Discussion

The present study sought to address critical gaps in several literatures—including those on depression, discrimination, and African American men’s health—by (a) examining the associations between major and everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms among African American men across the adult lifecourse, including young, middle, and older adulthood, (b) assessing the degree to which these two measures of discrimination vary in their impact on depressive symptoms among African American men, and (c) evaluating whether the relationships between discrimination and depressive symptoms among African American men is conditional on age—that is, does the direction and/or magnitude of the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms depend on the lifecourse stage (i.e., young adult, middle-aged, or older adult) for African American men?

Findings suggest that primarily everyday discrimination influences African American men’s depressive symptoms across the lifecourse. Among young African American men (under the age of 40), everyday but not major discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms. Interestingly, when both everyday and major discrimination were included in the analysis, the effect of everyday discrimination actually increased somewhat. A similar pattern was observed for middle-aged African American men, such that everyday, but not major, discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms. However, for older African American men, both major and everyday discrimination were associated with depressive symptoms. Compared to those with low exposure to major discrimination, those with moderate and high exposure to major discrimination had depression symptom scores, respectively, 4.5 and 5.1 points higher.

The results of the present study indicate that everyday and major discrimination do not have equal impacts on the mental health of African American men—at least those of younger and middle ages. Specifically, only experiences of major discrimination were associated with depressive symptoms among older African American men (age 55+). This is consistent with previous research that finds that everyday discrimination is more strongly associated with health compared to major discrimination (Ayalon & Gum, 2011; Williams, Yan, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). Everyday and major discrimination differ in important regards, including the timing of exposure (years ago or recently), whether experienced globally or in specific instances, and the intensity and frequency of discrimination (Krieger, 1999). In contrast to chronic diseases that are easier to prevent than reverse, a person may recover from depression and have subsequent episodes. Therefore, it seems to follow logically that everyday discrimination is more strongly associated with depression, as respondents are likely reporting on their recent experiences (whereas major discrimination experiences may have occurred years or even decades ago). The everyday discrimination measure also taps into global experiences more than the major discrimination measure. Finally, the everyday discrimination measure assesses the frequency of discrimination (e.g., “never” or “almost always”), whereas the major discrimination measure only asks respondents if they ever experienced specific events. The major discrimination measure does not assess whether each event occurred more than once or when such event(s) occurred.

Interestingly, although everyday discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms in all age groups, major discrimination was only related to depressive symptoms among older African American men. This may be due to the fact that such events have had a longer period of time to negatively affect economic status and employment trajectories, housing, health behaviors and other factors that could have downstream consequences for mental health (i.e., a snowball effect via indirect factors). It may also be the case that because older adults have lived longer, they have experienced some types of major discrimination more than once. Additionally, taking these results in historical perspective, it may be that this difference reflects a cohort effect, such that older adults who grew up prior to the Civil Rights Act are uniquely affected by experiences with major discrimination. For example, it may that experiences with major discrimination were even more extreme and/or impactful under Jim Crow law.

It is important to note that the older African American men in this study were more likely to report low major discrimination relative to younger men. This may also be due to poor recall of past events, such that those who do remember and report major events of discrimination, particularly those that happened long ago, may have been more adversely affected—either objectively in terms of more severe experiences, or subjectively, in terms of appraising it as a stressor (Charles et al., 2016). On the other hand, the effect of everyday discrimination was consistent across age groups, suggesting that ongoing discrimination may be easy to recall among men of all ages and that it has an equal and important impact on depressive symptoms regardless of lifespan developmental stage.

It also appears that the effect of everyday discrimination is independent of major discrimination among young and middle-aged African American men. Including major discrimination in models predicting depressive symptoms did not moderate the effect of everyday discrimination. However, there was a significant interaction between major and everyday discrimination for older African American men. Those who reported high major discrimination actually had fewer depressive symptoms if they also reported moderate or high everyday discrimination. Perhaps past experiences with major discrimination somehow equips older African American men to handle the stress of frequent everyday discrimination. It may be that being able to effectively cope with more frequent experiences of everyday discrimination by drawing on experience resulting from prior incidents somehow leaves older African American men with a sense of control. Among older adults, a positivity effect has been noted (Juang & Knight, 2016), and it is possible that discriminatory experience are interpreted in a less negative manner and may be appraised as less stressful (Whitehead & Bergeman, 2014), in line with the socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, 1995). This pattern may also be sociocultural in part. For example, older African American men may have been socialized to perceive and report depressive symptoms and/or major and everyday discrimination experiences differently than young and middle-aged African American men. This may reflect a form of emotion-focused coping in the face of the inability to change conditions with so few protections for African American men raised pre-Civil Rights. It also may be that experiences with everyday discrimination among older African American men reflect opportunities to interact in mainstream spaces where there is a greater likelihood of being exposed to everyday discrimination. There may be unique characteristics of the men who were in such a position pre-Civil Rights that contribute to these results. For instance, these men may have been more upwardly mobile relative to most African American men at the time.

Despite the important contributions of this study, several limitations must be noted. First, since the study employs cross sectional data, it is unclear if discrimination precedes depressive symptoms in temporal ordering. Therefore, it is possible that those who report more depressive symptoms perceive greater discrimination. However, a study by Brown and colleagues (2000) used longitudinal data and found that discrimination predicted depression, but not vice versa. Temporal ordering is also of less concern with respect to the major discrimination measure as many of these events could have occurred years or even decades prior to the study. However, we have no way of interrogating this question, as there is no information on when major discrimination experience(s) occurred or whether event(s) occurred the frequency with which they occurred. The present study also did not examine other psychosocial or behavioral factors that may mediate the association between discrimination and depressive symptoms. Previous work by our research team suggests that African Americans may utilize behavioral coping strategies to buffer the negative psychological impact of status-based stressors (Mezuk et al., 2010, 2013). Finally, this study utilized a regional dataset, so findings cannot be generalized beyond Davidson county/Nashville, TN.

Future studies are needed to examine longitudinal relationships between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among African American men across the adult lifecourse—perhaps even beginning in childhood and adolescence given what we know about how these sensitive developmental phases leave lasting imprints on health and well-being across the individual lifespan and also intergenerationally (Abdou, 2013; Abdou et al., 2010). There is also a need to examine appraisal of experiences of discrimination (Whitehead & Bergeman, 2014), including age, cohort and race/ethnic differences in appraisal and perceived stress (Vasunilashorn, Lynch, Glei, Weinstein & Goldman, 2014). In addition, the discrimination-health literature would be propelled forward by closer consideration of intersectionality theory and how experiences and outcomes are both similar and different as additional aspects of social identity are taken into account. For example, we need a more nuanced understanding how African American men and women are similar and different in their experiences of discrimination and its consequences across the lifecourse. Finally, prior studies have suggested that the link between discrimination and depression among African American men may be shaped by other social status dimensions, such as socioeconomic status. For example, Hudson (2012; Hudson et al., 2013) found that higher education is associated with greater exposure to discrimination and that the discrimination–depressive symptoms relationship may be greater among more educated African American men. Others have suggested that African Americans receive “diminishing returns” for higher educational attainment through increased interracial interactions, which may come with greater stress, and heightened awareness of institutional racism and experiences of interpersonal discrimination (Pearson, 2008; Thomas, 2015). Yet others call for a need to go beyond just years of education—to consider, for example, school segregation and the trend toward the erosion of desegregation gains (Aiken-Morgan, Gamaldo, Sims, Allaire & Whitfield, 2015). More attention is needed, as well, to how SES interacts with lifecourse stage to shape the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms and related health outcomes (Hudson et al., 2013). Specifically, more research is needed to understand the ways in which the relationship between discrimination and depression among African American men is conditioned by educational attainment and other indicators of SES and wealth across the lifecourse.

In terms of prevention and intervention, an important next step in the discrimination-health literature, including the discrimination–depression literature specifically, is to begin to examine psychosocial and cultural resources that may serve as buffers against discrimination and its mental and physical health consequences. The Culture and Social Identity Theory (CSIH) put forth by Abdou (2013) provides a systematic lens through which to examine the potential of health-protective cultural, social, and personal resources to buffer the mental health consequences of experiences with major and everyday discrimination among African American men (Abdou, 2013; Abdou et al., 2010).

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant P30-AG043073, RCMAR/CHIME NIH/NIA grant P30-AG021684 and UCLA CTSI NIH/NCATS grant UL1-TR000124. Courtney S. Thomas received support from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and Charles Drew University (CDU), Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME) under NIH/NIA Grant P30-AG021684, and from the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) under NIH/NCATS Grant Number UL1TR001881. Contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

The NSAHS was supported by a grant (R01AG034067) from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research and the National Institute on Aging to R. Jay Turner.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

F.V.W. submitted the original abstract for the special issue, assisted with conceptualization of the paper, performed analyses, and contributed to writing and revising the manuscript. C.S.T. performed analyses, assisted with conceptualization of the article, and contributed to writing and revising the manuscript. C.R. assisted with writing and revising the manuscript. C.M.A. supervised and contributed to conceptualization of the article, the data analytic strategy, and writing and revising of the manuscript.

References

- Abdou C. M., Dunkel Schetter C., Campos B., Hilmert C. J., Dominguez T. P., Hobel C. J.,…Sandman C (2010). Communalism predicts prenatal affect, stress, and physiology better than ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 395–403. doi:10.1037/a0019808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdou C. M., Schetter C. D., Jones F., Roubinov D., Tsai S., Jones L., … Hobel C (2010). Community perspectives: Mixed-methods investigation of culture, stress, resilience, and health. Ethnicity & Disease, 20, S2–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdou C. M. (2013). Aging before birth and beyond: Lifespan and intergenerational adaptation through positive resources. In K. E. Whitfield and T. Baker (Eds.) Handbook of minority aging. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Abdou C. M., & Fingerhut A. W (2014). Stereotype threat among black and white women in health care settings. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20, 316–323. doi:10.1037/a0036946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdou C. M., Fingerhut A. W., Jackson J. S., & Wheaton F (2016). Healthcare stereotype threat in older adults in the Health and Retirement Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50, 191–198. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken-Morgan A. T., Gamaldo A. A., Sims R. C., Allaire J. C., & Whitfield K. E (2015). Education desegregation and cognitive change in African American older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 348–356. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asante-Muhammed D., Collins C., Hoxie J. & Nieves E (2016). The Ever-Growing Gap. Institute for Policy Studies & CFED. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L., & Gum A. M (2011). The relationships between major lifetime discrimination, everyday discrimination, and mental health in three racial and ethnic groups of older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 15, 587–594. doi:10.1080/13607863.2010.543664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. N., Williams D. R., Jackson J. S., Neighbors H. W., Torres M., Sellers S. L., & Brown K. T (2000). “Being black and feeling blue”: The mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race and Society, 2, 117–131. doi:10.1016/S1090-9524(00)00010-3 [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. N., Turner R. J., & Moore T. R (2016). The multidimensionality of health: Associations between allostatic load and self-report health measures in a community epidemiologic study. Health Sociology Review, 25, 1–16. doi:10.1080/14461242.2016.1184989 [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L. L. (1995). Evidence for a life-span theory of socioemotional selectivity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4, 151–156. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep11512261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality.(2016). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 16–4984, NSDUH Series H-51) Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/

- Charles S. T., Piazza J. R., Mogle J. A., Urban E. J., Sliwinski M. J., & Almeida D. M (2016). Age differences in emotional well-being vary by temporal recall. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 798–807. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D. M., & Currie K. C (2009). Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: A review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. The Medical Journal of Australia, 190, S54–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P., & Smit F (2002). Excess mortality in depression: A meta-analysis of community studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 72, 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond W. P. (2012). Taking it like a man: Masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination-depressive symptoms association among African American men. American Journal of Public Health, 102, S232–41. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove T. W., & Brown T. H (2015). A life course approach to inequality: Examining racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between early life socioeconomic conditions and adult health among men. Ethnicity & Disease, 25, 313–320. doi:10.18865/ed.25.3.313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson D. L., Bullard K. M., Neighbors H. W., Geronimus A. T., Yang J., & Jackson J. S (2012). Are benefits conferred with greater socioeconomic position undermined by racial discrimination among African American men?Journal of Men’s Health, 9, 127–136. doi:10.1016/j.jomh.2012.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson D. L., Puterman E., Bibbins-Domingo K., Matthews K. A., & Adler N. E (2013). Race, life course socioeconomic position, racial discrimination, depressive symptoms and self-rated health.Social Science & Medicine, 97, 7–14. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ifatunji M. A., & Harnois C. E (2016). An explanation for the gender gap in perceptions of discrimination among African Americans: Considering the role of gender bias in measurement. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 2, 263–288. doi:10.1177/2332649215613532 [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y., Borenstein A. R., Chiriboga D. A., & Mortimer J. A (2005). Depressive symptoms among African American and white older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, P313–P319. doi:10.1093/geronb/60.6.P313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. P. (2000). Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 1212–1215. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang C., & Knight B. G (2016). Age differences in interpreting ambiguous situations: The effects of content themes and depressed mood. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 1024–1033. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Mickelson K. D., & Williams D. R (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 208–230. doi:10.2307/2676349 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek K. D., Murphy S. L., & Xu J. Q (2015)Deaths: Final data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. (1999). Embodying inequality: A review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 29, 295–352. doi:10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T. T., Cogburn C. D., & Williams D. R (2015). Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 407–440. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln K. D., Taylor R. J., Watkins D. C., & Chatters L. M (2011). Correlates of psychological distress and major depressive disorder among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(3), 278–288. doi:10.1177/1049731510386122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezuk B., Rafferty J. A., Kershaw K. N., Hudson D., Abdou C. M., Lee H., … Jackson J. S (2010). Reconsidering the role of social disadvantage in physical and mental health: Stressful life events, health behaviors, race, and depression. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172, 1238–1249. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezuk B., Johnson-Lawrence V., Lee H., Rafferty J. A., Abdou C. M., Uzogara E. E., & Jackson J. S (2013). Is ignorance bliss? Depression, antidepressants, and the diagnosis of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Health Psychology, 32, 254–263. doi:10.1037/a0029014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouzon D. M., Taylor R. J., Woodward A. T., & Chatters L. M (2016). Everyday racial discrimination, everyday non-racial discrimination, and physical health among African-Americans. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 26(1–2), 68–80. doi:10.1080/15313204.2016.1187103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Mental Health.(2013). Men and Depression Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/men-and-depression/index.shtml

- Pascoe E. A., & Smart Richman L (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 531–554. doi:10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J. A. (2008). ‘Can’t buy me whiteness: New lessons from the titanic on race, ethnicity and health.’Du Bois Review, 5, 27–48. doi:10.1017/S1742058X0808003X [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306 [Google Scholar]

- Priest N., Paradies Y., Trenerry B., Truong M., Karlsen S., & Kelly Y (2013). A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Social Science & Medicine, 95, 115–127. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G., Ormel J., VonKorff M., & Barlow W (1995). Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 352–357. doi:10.1176/ajp.152.3.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarupski K. A., Mendes de Leon C. F., Bienias J. L., Barnes L. L., Everson-Rose S. A., Wilson R. S., & Evans D. A (2005). Black-white differences in depressive symptoms among older adults over time. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, P136–P142. doi:10.1093/geronb/60.3.P136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. S. (2015). A new look at the Black middle class: Research trends and challenges. Sociological Focus, 48, 191–207. doi:10.1080/00380237.2015.1039439 [Google Scholar]

- Turner R. J., Thomas C. S., & Brown T. H (2016). Childhood adversity and adult health: Evaluating intervening mechanisms. Social Science & Medicine, 156, 114–124. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasunilashorn S., Lynch S. M., Glei D. A., Weinstein M., & Goldman N (2014). Exposure to stressors and trajectories of perceived stress among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 329–337. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E., & Mengesha M (2013). Depression in African American men: A review of what we know and where we need to go from here. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83, 386–397. doi:10.1111/ajop.12015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins D. C., Green B. L., Rivers B. M., & Rowell K. L (2006). Depression and black men: Implications for future research. Journal Men’s Health & Gender, 3, 227–235. doi:10.1016/j.jmhg.2006.02.005 [Google Scholar]

- Watkins D. C., Hudson D. L., Caldwell C. H., Siefert K., & Jackson J. S (2011). Discrimination, mastery, and depressive symptoms among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice, 21, 269–277. doi:10.1177/1049731510385470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead B. R., & Bergeman C. S (2014). Ups and downs of daily life: Age effects on the impact of daily appraisal variability on depressive symptoms. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 387–396. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbt019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Yan Yu, Jackson J. S., & Anderson N. B (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 335–351. doi:10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Neighbors H. W., & Jackson J. S (2003). Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 200–208. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]