Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the psychosocial mechanisms underlying older Black men’s self-rated health, we examined: (a) the individual, cumulative, and collective effects of stressors on health; (b) the direct effects of psychosocial resources on health; and (c) the stress-moderating effects of psychosocial resources.

Method

This study is based on a nationally representative sample of Black men aged 51–81 (N = 593) in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models of the psychosocial determinants of self-rated health draw on data from the HRS 2010 and 2012 Core datasets and Psychosocial Modules.

Results

Each of the six measures of stressors as well as a cumulative measure of stressors are predictive of worse self-rated health. However, when considered collectively, only two stressors (chronic strains and traumatic events) have statistically significant effects. Furthermore, two of the five psychosocial resources examined (mastery and optimism) have statistically significant protective effects, and prayer moderates the harmful effects of traumatic events on self-rated health.

Discussion

Conventional measures of stressors and coping resources—originally developed to account for variance in health outcomes among predominantly white samples—may not capture psychosocial factors most salient for older Black men’s health. Future research should incorporate psychosocial measures that reflect their unique experiences.

Keywords: Black men, Coping, Discrimination, Intersectionality, Self-rated health, Stress

Despite overall improvements in health and life expectancy over the last several decades, Black men continue to have some of the worst health profiles and shortest life expectancies of all race–gender groups in the United States (Gilbert et al., 2016). Importantly, the mechanisms underlying these health inequalities are not well understood, as the determinants of Black men’s health are rarely the focus of scholarly inquiry. Prior research shows that psychosocial factors such as stressors and coping resources affect physical health through multiple pathways (Pearlin, Schieman, Fazio, & Meersman, 2005; Thoits, 2010)—yet little is known about the extent to which such factors shape Black men’s health in later life (Thorpe, Duru, & Hill, 2015; Williams, 2003). Systematically investigating the psychosocial determinants of health among older Black men is especially important for several reasons. First, as a result of their intersecting racial and gender statuses, Black men experience psychosocial circumstances that are distinct from those experienced by their White and same-race female counterparts—circumstances that likely affect their health (Griffith, 2012; Watkins, Wharton, Mitchell, Matusko, & Kales, 2015). Second, the health of older Black men is shaped by their cumulative exposure to racialized and gendered risks, as well as their constrained access to salubrious resources over the life course (Brown, Hargrove, & Griffith, 2015). Third, a better understanding of the determinants of health among this vulnerable population is needed to develop efficacious strategies for eliminating health disparities and improving population health.

The Stress Process Model (SPM) is a leading framework in the social sciences that links psychosocial factors to health (Pearlin et al., 2005). Three key propositions undergird this model: (a) social context shapes exposure to stressors and access to coping resources, (b) stressors negatively affect health, and (c) social and personal resources positively influence health, both directly and indirectly by reducing the negative effects of stressors (Keith, 2014; Turner, 2013). Although research on the SPM has produced a wealth of knowledge regarding the social stratification of health, the extent to which this model adequately captures the psychosocial mechanisms underlying health among Black men in particular remains unclear. This is mainly because previous studies have often been based on majority-white samples or focused on between-group differences in health by either race or gender. A common limitation of this literature has been the implicit, tenuous assumption that relationships between psychosocial factors and health are similar across social groups. Such an assumption does not take into account the drastic differences in experiences and social realities faced by those located at varying intersections of race and gender hierarchies (Collins, 2015). The extent to which pathways to health may differ among broadly defined social groups is therefore unclear. To address this limitation of prior research, it is important to utilize a within-group approach to explicitly examine the psychosocial determinants of Black men’s health (Whitfield, Allaire, Belue, & Edwards, 2008).

Assessing the psychosocial mechanisms underlying Black men’s health is a growing topic of research, though the literature has been limited in several respects. For example, many studies have relied on small convenience samples or local epidemiologic surveys, limiting the generalizability of this research. Additionally, prior studies have tended to examine a single or small set of psychosocial factors, overlooking the cumulative and collective consequences of numerous psychosocial stressors and resources. Inattention to the simultaneous impacts of a range of psychosocial factors likely masks their unique effects on health (Thoits, 2010). Moreover, previous work has rarely examined the psychosocial determinants of Black men’s physical health in later life. These gaps in the literature hinder our understanding of how psychosocial processes that operate across the life course shape Black men’s health at older ages.

This study extends prior research by drawing on stress process (Pearlin et al., 2005) and intersectionality perspectives (Collins, 2015) to examine the extent to which an array of psychosocial factors impact health among a nationally representative sample of older Black men. In particular, we focus on three research objectives. First, we examine the individual, collective, and cumulative impact of commonly-used measures of stressors (e.g., discrimination, chronic and financial strains, traumas, and negative life events) on Black men’s health. Second, we investigate whether social and personal resources (e.g., social support, mastery, optimism, religiosity, and prayer) are protective for Black men’s health. Third, we examine the extent to which social and personal resources moderate the effects of stressors on health among older Black men. We focus on self-rated health in particular because it is a reliable and valid global measure of health, and it is predictive of subsequent morbidity and mortality (Brown, Richardson, Hargrove, & Thomas, 2016; Idler & Benyamini, 1997). Additionally, it does not require a clinical diagnosis, thereby minimizing potential biases stemming from racial and gender differences in health care access and utilization. Results of this study will provide critical insight into how well conventional psychosocial measures capture the mechanisms shaping older Black men’s health, and they will help inform policies and interventions aimed at improving their health.

Theoretical Framework

The SPM is a prominent framework that helps elucidate the health consequences of one’s location in the social structure. Specifically, this model attributes social inequalities in health to interrelationships among social contexts, stressors, social and personal resources, and manifestations of stress (Keith, 2014; Pearlin et al., 2005). Indeed, research provides strong support for the claim that stressors lead to worse physical health due to repeated activation of the body’s stress response (Thoits, 2010). This ongoing physiological activation has deleterious effects on a range of bodily systems, such as the immune, neuroendocrine, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular systems (Bruce, Griffith, & Thorpe, 2015; McEwen & Seeman, 1999). Stressors also indirectly affect physical health by inducing negative emotional states and engagement in unhealthy coping behaviors (Jackson, Knight, & Rafferty, 2010). Furthermore, there has been considerable support for the SPM’s prediction that social and personal resources have both direct and stress-buffering effects on health (Wheaton, 2009). Another central proposition of the model is that stress exposure and the availability of coping resources are shaped by one’s social context (Pearlin, 1989). Consistent with this assertion, studies show that exposure to stressors and access to psychosocial resources vary along racial and gender lines (Keith, 2014; Thoits, 2010). However, few studies in the stress literature have examined the joint consequences of race and gender on the distribution of psychosocial risks and resources, and the processes through which they affect health.

Within the men’s health literature, there is a growing recognition of the importance of taking an intersectional approach to examining how race and gender combine to shape the experiences of Black men (Gilbert et al., 2016). Due to their dominant positions in the gender hierarchy as men, but subordinate positions as racial minorities, Black men face a number of unique gendered social norms and cultural expectations that, along with race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), and age, may negatively shape their behaviors and health (Griffith, Metzl, & Gunter, 2011). Moreover, distress associated with their status inconsistency (simultaneous membership in the dominant gender group and subordinate racial group) may be particularly pronounced for current cohorts of older Black men given that they came of age during an era characterized by rampant overt and de jure sexism and racism (Bonilla-Silva, 2014; Krieger, 2014). Indeed, research indicates that Black men often experience distress associated with trying to achieve hegemonic gender expectations (e.g., fulfilling the traditional role as economic provider for their families) in spite of their constrained economic opportunities, as well as their exposure to racial discrimination in many areas of life including educational and criminal justice systems, and labor, housing, consumer and credit markets (Gilbert et al., 2016; Pager & Shepherd, 2008; Pettit & Western, 2004; Williams, 2003). In addition, Black men are subjected to unique forms of gendered racial discrimination (Collins, 2015; Taylor, Miller, Mouzon, Keith, & Chatters, 2016) and tend to experience especially high levels of financial strain and chronic stressors (Brown et al., 2015).

Scholars have theorized that stress resulting from gendered racial inequality is likely to accumulate and compound over the life course, contributing to high rates of unhealthy behaviors, poor health, and premature mortality among Black men (Thorpe et al., 2015). However, little is known about the individual, collective, and cumulative consequences of an array of stressors on Black men’s health, especially in later life. Furthermore, although studies point to the health benefits of social support and religion for Black Americans specifically (Taylor, Chatters, & Levin, 2004; Watkins et al., 2015), no study has systematically examined the joint and potentially interactive effects of a broad range of stressors and psychosocial resources within a nationally representative sample of older Black men.

Scant attention to the unique psychosocial pathways that shape Black men’s health may reflect an implicit assumption among previous studies that the SPM is invariant across subpopulations. A central tenet of the SPM is that one’s social location conditions the amount and kinds of stress to which one is exposed, the resources one has to cope with such stress, and the manner in which stress is experienced and manifested (Pearlin, 1989; Williams, Costa, & Leavell, 2010). In practice, however, little attention has been given to whether the psychosocial stressors and resources most relevant for health may differ across population subgroups. Given that Black men face unique experiences across many domains of life, it is possible that conventional measures of psychosocial factors, originally developed to explain variations in health among largely white samples, may not adequately capture complex psychosocial-health processes among this marginalized group.

Stressors and Health

Over the last half century, substantial evidence has accumulated indicating that social stressors have deleterious effects on health. Scholarship in this area has generally focused on specific discrete and chronic stressors, including discrimination (e.g., major events such as being unfairly fired or denied a promotion; everyday experiences with discrimination such as being treated with less courtesy), chronic strains (e.g., work-family conflict), traumas (e.g., being a victim of or witnessing violence), recent life events (e.g., involuntary job loss), and financial strain (e.g., difficulty paying bills)—showing that each has harmful effects on mental and physical health (Thoits, 2010; Turner, Thomas, & Brown, 2016; Umberson et al., 2016; Williams & Mohammed, 2013). Furthermore, a study by Sternthal, Slopen, & Williams (2011) illustrates the importance of examining the effects of cumulative stress exposure, as well as the collective effects of numerous stressors in order to determine their unique impacts on health.

The robust relationship found between these stressors and health, coupled with findings that social location shapes exposure to stressors, suggests that stress is a primary mechanism through which inequality “gets under the skin” (Turner, 2013). Indeed, results from a recent study indicate that Black men have particularly high levels of exposure to both everyday and major discrimination, chronic stressors, and financial strain, and that these factors contribute to their poorer health relative to White men (Brown et al., 2015). Previous studies, however, have rarely focused on the physical health of older Black men, and typically have not considered how the impact of individual stressors is influenced by exposure to an array of other simultaneously experienced stressors as well as access to psychosocial resources.

Social and Personal Resources and Health

In addition to highlighting the effects of stressors on health, the SPM predicts that psychosocial resources impact health outcomes both directly and indirectly by buffering the negative impacts of stressors (Keith, 2014). There is considerable evidence of the protective and stress-moderating effects of numerous social and personal resources including: social support (Thomas, 2016), religious beliefs and practices (e.g., belief in the afterlife, church attendance, and prayer; George, Kinghorn, Koenig, Gammon, & Blazer, 2013), mastery (i.e., sense of one’s life chances being under one’s own control; Mizell, 1999; Pearlin, 1999), and optimism (i.e., view that the future will be pleasant; Rasmussen, Scheier, & Greenhouse, 2009). Importantly, social support, religion, and faith have long been considered key sources of strength and resilience, especially among Blacks (Stack, 1974; Taylor et al., 2004). As an adaptive response to constrained opportunities and elevated exposure to stressors stemming from structural racism, Blacks mobilize support from their extended kin networks to ascertain a variety of health-relevant social, economic, and psychological resources (Stack & Burton, 1993; Taylor, Mouzon, Nguyen, & Chatters, 2016). Furthermore, given the historical and contemporary centrality of the church in the Black community, it is not surprising that Blacks have especially strong religious beliefs and high levels of church attendance and prayer (Taylor et al., 2004). In turn, these religious beliefs, practices and experiences appear to have salutary effects for older Blacks’ mental and physical health (Ellison, Hummer, Cormier, & Rogers, 2000; Taylor et al., 2004; Watkins et al., 2015).

Overall, existing evidence suggests that several psychosocial resources are important determinants of older Black men’s health. A number of gaps in the literature, however, prevent a comprehensive evaluation of this hypothesis. Importantly, research to date has not examined the individual and joint consequences of a range of psychosocial resources, particularly within the context of stress exposure and among a nationally representative sample of older Black men. Consequently, the extent to which stressors and social and psychological resources combine to shape health among older Black men remains unclear.

The Current Study

Our study is guided by three research questions. First, to what extent do social stressors individually, cumulatively and collectively affect older Black men’s self-ratings of health? Second, are social and personal resources directly protective of older Black men’s health? Third, to what extent do social and personal resources buffer the negative impacts of stressors on health among older Black men? Addressing these questions is essential for understanding the psychosocial determinants of health among a population that experiences unique social and economic disadvantages as well as a disproportionate burden of poor health.

Data and Methods

Sample

This study uses data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative study of U.S. adults over the age of 50. Blacks and Hispanics were oversampled to facilitate independent analysis of racial/ethnic groups. We combine information from the 2010 and 2012 Core Data and Psychosocial Modules (see Servais (2010) and Smith et al. (2013) for detailed information on these data sources). Half of the core panel participants were randomly assigned to complete the Psychosocial Module in 2010; the other half of the sample was assigned to complete the module in 2012. Although psychosocial data was also collected in 2006 and 2008, it is not included in this study due to inconsistent measurement of psychosocial factors between those years and 2010 and 2012. The analytic sample for this study includes U.S.-born respondents who self-identify as male and African American or Black, and are aged 51–81 years (1931–1959 birth cohorts) at the time of the interview (N = 593).

Outcome Measure

Self-rated health is measured by respondents’ answers to the question, “In general, would you say your health is: excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”; responses ranged from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). This global measure of health has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of general health status among diverse populations in the U.S. (Brown et al., 2016; Idler & Benyamini, 1997). Supplemental analyses (available upon request) indicated that self-rated health at baseline is predictive of subsequent chronic conditions, disability, and mortality (net of SES factors) among older Black men in this study.

Covariates

Consistent with prior investigations of the stress-health relationship, we examine the impacts of several widely-used measures of psychosocial factors. Measures of stressors include everyday discrimination, major discrimination, chronic stressors, traumatic events, stressful life events, and financial strain. Stressors associated with perceived discrimination are captured using the validated Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997; 6-item mean index; α = .840) that assesses how often respondents experience daily hassles associated with perceived unfair treatment, as well as the Major Discrimination Scale (Williams et al., 1997; 7-item inventory), which captures perceptions of significant discriminatory events in various domains such as work, housing, lending, and criminal justice and health care systems. Chronic stressors (Troxel, Matthews, Bromberger, & Sutton-Tyrrell, 2003; 6-item inventory) include current and ongoing problems that have lasted twelve months or longer such as having a family member who has health problems or abuses drugs or alcohol; difficulties at work; housing problems; and strain in a close relationship. The measure of traumatic events (Krause, Shaw, & Cairney, 2004; 7-item inventory) assesses major acute stressors over the life course, such as the death of a child; natural disasters; combat involving firearms; and substance abuse or life threatening illnesses or accidents among family members. A five-item inventory of stressful life events over the last 5 years (Turner, 2013) summarizes recent acute stressors including involuntary job loss; prolonged unemployment for the respondent and other household members; moving to a worse residence or neighborhood; and robbery or burglary. An index of financial strain (Campbell, Converse, & Rodgers, 1976) assesses difficulty in meeting monthly payments on bills, ranging from 1 (not at all difficult) to 5 (completely difficult). We also include a cumulative measure of exposure to stressors (i.e., the number of stressors for which the respondent is in the highest-risk quartile; see Sternthal et al., 2011).

Measures of social and personal resources include positive social support, sense of mastery, optimism, religiosity, and frequency of prayer. A measure of positive social support (Cohen, 2004; 3-item mean index; α = .851) taps perceptions about emotional and instrumental support from family and friends, with response categories ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot). The mastery measure (7-item mean index; α = .760) is derived from the Pearlin Mastery Scale (Pearlin, 1999) and assesses the degree to which respondents believe that their life chances are under their own control. A 3-item mean index (α = .738) captures dispositional optimism overall and with respect to the future and uncertain times (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). Religiosity (George et al., 2013) is measured by a 4-item mean index of religious beliefs, meaning and values (α = .927). Response categories for mastery, optimism and religiosity measures range from 1 to 6, with higher values indicating greater degrees of these constructs. Frequency of prayer (Taylor et al., 2004) is assessed by a single item, ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (more than once a day). To minimize the risk of biased estimates of the effects of psychosocial factors on health, all analyses adjust for several control variables including age (measured in years), years of education, logged household income, logged wealth, marital status, and year of interview. Detailed information on the operationalization of the study variables is included in the online Supplementary Material (see Supplementary Table A1), and weighted descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Weighted Means and Proportions of Study Variables Among Older Black Men in the HRS (N = 593)a

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Self-rated health | 2.924 | (.057) |

| Stressors | ||

| Everyday discrimination | 1.885 | (.057) |

| Major discrimination | 1.134 | (.076) |

| Chronic stressors | 3.308 | (.114) |

| Traumatic events | 1.176 | (.063) |

| Stressful life events | 0.567 | (.044) |

| Financial strain | 2.425 | (.054) |

| Cumulative stressors | ||

| High risk on 1 or no stressors | 0.375 | |

| High risk on 2 stressors | 0.228 | |

| High risk on stressors | 0.194 | |

| High risk on 4 or more stressors | 0.203 | |

| Coping resources | ||

| Positive social support | 3.031 | (.034) |

| Mastery | 4.800 | (.055) |

| Optimism | 4.621 | (.061) |

| Religiosity | 5.197 | (.074) |

| Frequency of prayer | 4.330 | (.105) |

| Controls | ||

| Age | 62.225 | (.373) |

| Education | 12.203 | (.138) |

| Income (Ln) | 10.016 | (.115) |

| Wealth (Ln) | 6.740 | (.414) |

| Married | 0.629 | |

| Measures from 2012 | 0.514 | |

Note: 2010–2012 Health and Retirement Study. HRS = Health and Retirement Study.

aMeans for dummy variables can be interpreted as the proportion of the sample coded 1 on that indicator.

Analytic Strategy

OLS regression models are utilized to examine the relationships among psychosocial stressors, coping resources, and self-rated health. For ease of interpretation, we use a linear specification for the regression models, although supplemental analyses suggest that results are robust to alternative specifications (e.g., ordered logit). Estimates from regression models are reported as standardized coefficients. Psychosocial measures are introduced in a sequential manner in order to estimate (a) the individual, cumulative, and collective effects of stressors (Table 2, Columns 1–3, respectively); (b) the individual and collective effects of psychosocial resources (Table 2, Columns 4 and 5, respectively); and (c) the collective and interactive effects of stressors and psychosocial resources (Table 2, Columns 6 and 7, respectively). All analyses utilize sampling weights and are estimated using STATA 14.1.

Table 2.

Effects of Psychosocial Stressors and Resources on Self-rated Health Among Older Black Men (N = 593)a,b

| 1c,j | 2d | 3e | 4f,j | 5g | 6h | 7i | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stressors | |||||||

| Everyday discrimination | −.121** | −.038 | −.017 | −.013 | |||

| Major discrimination | −.126* | −.028 | −.024 | −.034 | |||

| Chronic stressors | −.243*** | −.180** | −.163* | .179** | |||

| Traumatic events | −.203*** | −.154** | −.146** | −.430*** | |||

| Stressful life events | −.120* | −.036 | −.024 | −.021 | |||

| Financial strain | −.165** | −.089 | −.084 | −.084 | |||

| Cumulative stressors | |||||||

| High risk on 1 or no stressors (ref. group) | |||||||

| High risk on 2 stressors | −.034 | .069 | .068 | .074 | |||

| High risk on 3 stressors | −.100* | .063 | .049 | .057 | |||

| High risk on 4 or more stressors | −.252*** | .043 | .028 | .030 | |||

| Social and personal resources | |||||||

| Positive social support | .129** | .106 | .041 | .049 | |||

| Mastery | .170** | .138* | .122* | .118* | |||

| Optimism | .128* | .098* | .108* | .109* | |||

| Religiosity | .037 | .042 | .036 | .038 | |||

| Frequency of prayer | −.069 | −.101 | −.078 | −.098** | |||

| Interactions between stressors and resources | |||||||

| Traumatic events × Frequency of prayer | .055** | ||||||

| Intercept | |||||||

| R 2 | .180 | .219 | .184 | .255 | .271 | ||

Note: 2010–2012 Health and Retirement Study.

aEstimates from ordinary least squares regression models; standardized coefficients are presented. bAll models control for age, education, income, wealth, marital status, and the year of interview. cSeparate models for each stressor. dSingle model including number of stressors in the highest-risk quartile. eSingle model of the collective effects of individual stressors and number of stressors in the highest risk quartile. fSeparate models for each social and personal resource. gSingle model including all five social and personal resources simultaneously. hFull model of the collective effects of all stressors and coping resources. iFull model with collective effects and statistically significant interactions between stressors and resources. jFor the sake of concision, model fit statistics are not shown for the separate models (available upon request).

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Results

Results from column 1 of Table 2 show estimates from separate models that examined the individual effects of each stressor. Findings indicate that, when examined individually, all of the stressors are statistically significant predictors of self-rated health. Specifically, everyday discrimination, major discrimination, chronic stressors, traumas, stressful life events, and financial strains are all associated with worse self-rated health. In addition, results from column 2 of Table 2 indicate that cumulative exposure to stressors is associated with health: compared to individuals who are in the highest-risk quartile on none or one of the stressors, those who are in the highest-risk quartile for three or four or more stressors have worse self-rated health.

Results shown in column 3 are based on estimates from a model that included the collective effects of each individual stressor as well as the cumulative stressors. When considered simultaneously, only chronic stressors and traumatic events have statistically significant negative effects on self-rated health. Findings from this model suggest that the number of stressors one is exposed to is not predictive of self-rated health, net of the collective effects of each stressor.

Column 4 of Table 2 presents estimates from separate models of the individual effects of psychosocial resources. In these models, higher levels of social support, mastery, and optimism are predictive of better self-rated health. However, when considered collectively (column 5), only mastery and optimism have statistically significant protective effects. Column 6 shows estimates from a model of the collective effects of all stressors and social and personal resources. Whereas chronic strains and traumatic events are the only stressors that are predictive of self-rated health, mastery and optimism are the only resources that have statistically significant protective effects. The fact that these results are similar to those presented in columns 3 and 5, suggests that personal resources do not mediate the effects of stressors on health (and vice versa).

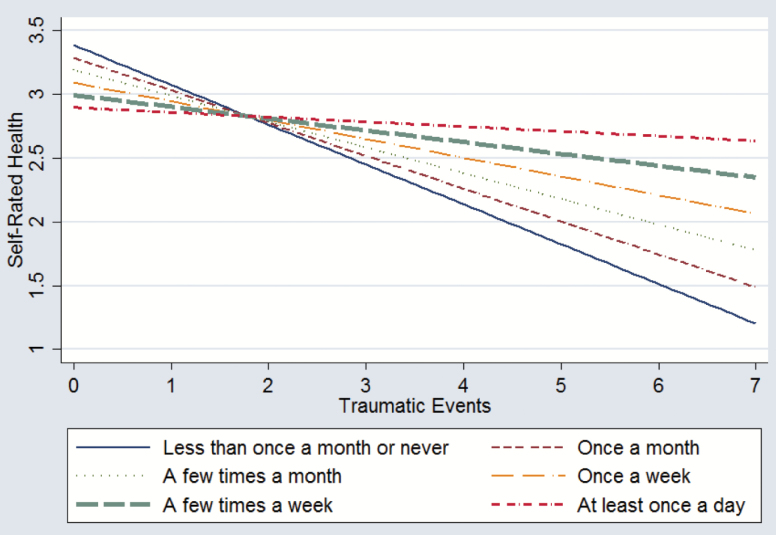

Ancillary analyses (available upon request) examined potential moderating effects of each of the psychosocial resources on each of the stressors, though the only statistically significant interaction was between traumas and prayer. Results from column 7 of Table 2 reveal that frequency of prayer buffers the negative effects of traumatic events on self-rated health. Figure 1 graphically illustrates how traumas have less harmful effects on self-rated health among individuals who pray more frequently, compared to those who pray less frequently. This figure also shows that whereas greater frequency of prayer is associated with slightly worse self-rated health among individuals who report zero or one traumatic event, it is has strong protective effects among those who have experienced numerous traumas. Supplemental analyses (not shown for the sake of concision) also indicated that many of the control variables were associated with self-rated health in expected ways. For example, age was predictive of worse self-rated health, while education, income, and wealth were protective of self-rated health. Marriage and year of interview were not associated with self-rated health. The R2 statistic for the model presented in column 7 indicates that the model explains 27.1% of the variation in self-rated health.

Figure 1.

The impact of traumatic events on self-rated health, by frequency of prayer.

Discussion

Given that Black men have some of the worst health profiles and shortest life expectancies of all race–gender groups in the U.S., it is especially important to understand the psychosocial determinants of their health (Thorpe & Halkitis, 2016). While research on the SPM has provided ample evidence that psychosocial factors affect health, the extent to which commonly-measured stressors and coping resources adequately capture key psychosocial mechanisms that shape health among older Black men in particular remains unclear. This study is among the first to systematically examine the effects of a wide range of psychosocial stressors and resources among a nationally-representative sample of older Black men.

Findings illustrate the importance of examining the combined effects of numerous stressors rather than focusing on the consequences of individual stressors. Initial analyses in this study suggested that when considered individually, all of the stressors and the number of cumulative exposures to stressors were predictive of worse self-rated health. However, subsequent analyses that investigated the collective effects of stressors revealed that only two of the six stressors—chronic stressors and traumatic life events—had independent effects on self-rated health. This result is consistent with previous research documenting the particularly harmful effects of stressors that are recurring and/or severe (Thoits, 2010). Importantly, differences in the predictive power of stressors when considered individually versus in the context of other stressors underscore the importance of investigating numerous stressors that are experienced simultaneously to determine their unique effects on health.

Our findings also provide mixed evidence for the protective effects of social and personal resources considered in this study, and limited support for the notion that they operate as stress buffers among older Black men. When psychosocial resources were considered collectively, two of the five psychosocial resources examined—mastery and optimism—were significantly protective of self-rated health. Moreover, investigations of all possible stress-buffering processes revealed only one instance of stress-moderating effects. Specifically, greater frequency of prayer buffers the deleterious effects of traumatic events on self-rated health. These results highlight the importance of considering the impacts of individual psychosocial resources within the context of a wide array of other stressors and coping resources.

Overall, results from this study suggest that commonly-used psychosocial measures are moderately predictive of self-rated health among older Black men. There are several possible explanations for, and implications of, these findings. For example, scholars have posited that late life stressors may have muted effects on the health of older Blacks. These relatively moderate effects may be attributed to two factors: (a) older Black men, who have often endured elevated exposure to stressors throughout their lives, have become accustomed to managing stressors; and (b) mortality selection prior to late life leads to samples of older Black men who primarily represent those who are most resilient or adept at coping with the harmful effects of stressors (Ayalon & Gum, 2011; Barnes et al., 2008). A key implication of findings from this study is that conventional measures of stressors and coping resources—originally developed to account for variance in health outcomes among predominantly white samples—may not fully capture the psychosocial factors most salient for older Black men’s health. Thus, it is important that future research on older Black men’s health incorporates measures of stressors and resources that better reflect their experiences. One source of stress that is unique to men of color stems from racialized understandings and expectations surrounding gender and masculinity. For example, older Black men likely experience distinctive forms of distress as a result of their efforts to attain statuses and fulfill roles that conform to hegemonic gender expectations, while also experiencing constrained economic opportunities due to discrimination across myriad domains (Williams, 2003). Griffith, Gunter, and Watkins (2012) also highlight the importance of considering how masculinities in general and Black masculinities in particular are shaped by structural forces and cultural expectations, which ultimately lead to poor health. They note that several aspects of masculinity (e.g., male norms, masculine ideologies, and machismo) are associated with distress, though relatively little is known about the effects of racialized masculinities on physical health.

Furthermore, experiences of discrimination other than those traditionally measured are likely relevant for the physical health among older Black men. Given that discrimination attributable to being a Black man is distinct from discrimination attributable to being Black and a man (e.g., the sum of racial and gender discrimination; Brown et al., 2016; Collins, 2015), it may be useful to explicitly examine the impact of gendered racial discrimination for Black men’s health. For example, Black men’s disproportionately high risks of contact with the criminal justice system (Alexander, 2010; Pettit & Western, 2004) likely play a significant role in shaping their health. Indeed, previous research suggests that incarceration has deleterious health consequences because it is distressing, stigmatizing, increases exposure to infectious diseases, and often leads to stress proliferation across many areas of life such as unemployment, financial hardship, and family strain (Massoglia & Pridemore 2015).

Stressors beyond the individual level are also important for understanding the stress-health link among Black men. For example, Black men may experience stress vicariously as a result of family and close friends being exposed to race-based and general stressors (Williams & Mohammed, 2013). Neighborhood stressors such as exposure to toxins, violence, and surveillance may also negatively affect Black men’s health (Williams, 2003). Indeed, a recent study by Ray (2017) suggests that middle class Black men are less likely to be physically active in predominantly White neighborhoods than in racially diverse or predominantly Black neighborhoods because they do not feel comfortable in these spaces due to negative stereotypes about the criminality of Black men. Moreover, Lewis, Cogburn, & Williams (2015) posit that macro-level or large-scale stressors such as highly-publicized instances of police brutality and wrongful convictions are likely to cause distress for minorities. Awareness of these incidents may be particularly stressful for Black men given that they are often the victims of these tragic events. Further research is needed to identify the multilevel stressors that are most influential in shaping older Black men’s health.

Findings from this study also raise questions about why several of the social and personal resources examined were not protective of health and whether there are other psychosocial factors that may be sources of resilience for Black men’s health. While the precise explanation for the modest direct and moderating effects of psychosocial resources is unclear, it is plausible that their salutary effects are diluted or offset by the pervasive and cumulative adversity that many older Black men have endured over their lives. By middle or later life, Black men have been exposed to more than a half century of various forms of racism (e.g., institutional, interpersonal, vicarious, internalized, cultural, etc.), which has often resulted in the experience of substantial social, economic, psychological, and health disadvantages (Brown et al., 2015; Keith, 2014). Under these circumstances, the contemporaneous social and personal resources examined in this study may not be adequate for ameliorating Black men’s cumulative adversity and stress burden. The literature is not clear about which psychosocial resources are likely to be most salubrious for older Black men. Previous studies have suggested that strong racial identity is protective and buffers the effects of discrimination on Blacks’ psychological well-being (Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, & Zimmerman, 2003), though the evidence is mixed and little is known about the effects of racial identity on older Black men’s physical health. We echo Watkins and colleagues’ (2015) call for further research that utilizes mixed methods and qualitative approaches for identifying the availability and effectiveness of culturally appropriate coping mechanisms among older Black men.

It is important to note several limitations of the current study. First, given the cross-sectional nature of our analyses, we are unable to examine lagged effects or rule out the possibility of reverse causality, though there is solid evidence from previous longitudinal studies suggesting that psychosocial factors have causal effects on health (Thoits, 2010). A second limitation of the study concerns possible selection biases. Specifically, because this study does not include Black men who died before age 50, or those who are homeless or institutionalized (e.g., incarcerated or living in a nursing home), we are likely missing Black men who are most disadvantaged with respect to stress exposure, coping resources, and health. Thus, findings are only generalizable to community-dwelling Black men who survive past the age of 50. Third, due to data limitations, this study is unable to fully capture life course processes shaping older Black men’s health. Research suggests that cumulative adversity and stressors across the life course, especially during early life, negatively affect subsequent attainment processes, stress exposure, availability of coping resources, and ultimately, late life health (Ferraro et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2016). Fourth, it is beyond the scope of this study to identify the specific biological pathways through which psychosocial factors shape various health outcomes. Future research should address these important topics as well as the extent to which psychosocial mechanisms underlying Black men’s health are contingent on social factors such as class, skin color, nativity, and sexuality (Gilbert et al., 2016).

Despite these limitations, this study makes several contributions to the literature. Importantly, this study makes visible the experiences of an often-overlooked social group and highlights how their unique position in the social hierarchy differentiates the mechanisms underlying health. Furthermore, in addition to identifying the health consequences of specific psychosocial factors among older Black men, results from this study underscore the importance of considering the collective and cumulative effects of an array of stressors and resources in order to understand complex psychosocial processes. More broadly, findings from this study indicate that commonly-used measures of psychosocial factors have limited utility for understanding older Black men’s self-rated health, as evidenced by their modest explanatory power among this population subgroup. This suggests that scholars should not assume that the SPM works similarly across or within diverse groups. Rather, results from this study underscore the need for future research that examines how health is shaped by a more comprehensive set of psychosocial stressors and resources that better reflect the experiences of older Black men. Valuable information gained from this line of research will be critical for developing policies and interventions aimed at improving their health.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences online.

Funding

This study was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant/Award Number: 64300) and National Institute on Aging (Grant/Award Number: 7R01AG054363-02, P30AG034424).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Alexander M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L. & Gum A. M (2011). The relationships between major lifetime discrimination, everyday discrimination, and mental health in three racial and ethnic groups of older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 15, 587–594. doi:10.1080/13607863.2010.543664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes L. L. de Leon C. F. Lewis T. T. Bienias J. L. Wilson R. S. & Evans D. A (2008). Perceived discrimination and mortality in a population-based study of older adults. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1241–1247. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.114397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E. (2014). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States (4th ed). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. H. Richardson L. J. Hargrove T. W. & Thomas C. S (2016). Using multiple-hierarchy stratification and life course approaches to understand health inequalities: The intersecting consequences of race, gender, SES, and age. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 57, 200–222. doi:10.1177/0022146516645165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. H. Hargrove T. W. & Griffith D. M (2015). Racial/ethnic disparities in men’s health: Examining psychosocial mechanisms. Family & Community Health, 38, 307–318. doi:10.1097/FCH.0000000000000080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M. A. Griffith D. M. & Thorpe R. J. Jr (2015). Social determinants of men’s health disparities. Family & Community Health, 38, 281–283. doi:10.1097/FCH.0000000000000083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A., Converse P.E., & Rodgers W (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions.New York: Russell Sage Foundation. doi:10.2307/2066476 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. (2004). Social relationships and health. The American Psychologist, 59, 676–684. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology 41:1–20. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142 [Google Scholar]

- Ellison C. G., Hummer R. A., Cormier S. M., & Rogers R. G (2000). “Religious involvement and mortality risk among African American adults.”Research on Aging 22, 630–667. doi:10.1177/0164027500226003 [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro K. F. Schafer M. H. & Wilkinson L. R (2016). Childhood disadvantage and health problems in middle and later life: Early imprints on physical health?American Sociological Review, 81, 107–133. doi:10.1177/0003122415619617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George L. K. Kinghorn W. A. Koenig H. G. Gammon P. & Blazer D. G (2013). Why gerontologists should care about empirical research on religion and health: Transdisciplinary perspectives. The Gerontologist, 53, 898–906. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert K. L., Ray R., Siddiqi A., Shetty S., Elder K., Baker E., & Griffith D. M (2016). Visible and invisible trends in African American men’s health: Pitfalls and promises for addressing inequalities. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 295–311. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M. Metzl J. M. & Gunter K (2011). Considering intersections of race and gender in interventions that address US men’s health disparities. Public Health, 125, 417–423. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2011.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M. (2012). An intersectional approach to men’s health. Journal of Men’s Health, 9, 106–112. doi:10.1177/1557988313480227 [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M. Gunter K. & Watkins D. C (2012). Measuring masculinity in research on men of color: Findings and future directions. American Journal of Public Health, 102(Suppl. 2), S187–S194. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E. L. & Benyamini Y (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21–37. doi:10.2307/2955359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J. S., Knight K. M., & Rafferty J. A (2010). Race and unhealthy behaviors: Chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. American Journal of Public Health, 100(5), 933–939. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith V. M. (2014). Stress, discrimination, and coping in late life. In K. E. Whitfield & T. Baker (Eds.), Handbook of minority aging (pp. 65–84). New York: Springer. doi:10.1017/S0714980814000257 [Google Scholar]

- Krause N., Shaw B. A., & Cairney J, (2004). A descriptive epidemiology of lifetime trauma and the physical health status of older adults.Psychology and Aging, 19(4), 637–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. (2014). Discrimination and health inequities. In L. F. Berkman I. Kawachi, & M. Glymour (Eds.). Social Epidemiology (2nd ed, pp. 63–125). New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780195377903.003.0003 [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T. T. Cogburn C. D. & Williams D. R (2015). Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: Scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 407–440. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoglia M. & Pridemore W (2015). Incarceration and health. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 291–310. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S., & Seeman T (1999). “Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress: Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load.”Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 30–47. doi:10.1111/j.1749–6632.1999.tb08103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizell C. A. (1999). African American men’s personal sense of mastery: The consequences of the adolescent environment, self-concept and adult achievement. Journal of Black Psychology, 25, 210–230. doi:10.1177/0095798499025002005 [Google Scholar]

- Pager D. & Shepherd H (2008). The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 181–209. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. (1989). The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30(3), 241–256. doi:10.2307/2136956 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I. (1999). The stress process revisited: Reflections on concepts and their interrelationships. In C. S. Aneshensel & J. C. Phelan (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 395–415). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. doi:10.1007%2F978-94-007-4276-5 [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I. Schieman S. Fazio E. M. & Meersman S. C (2005). Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 205–219. doi:10.1177/002214650504600206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit B., & Western B (2004). Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. American Sociological Review, 69, 151–169. doi:10.1177/000312240406900201 [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen H. N. Scheier M. F. & Greenhouse J. B (2009). Optimism and physical health: A meta-analytic review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 239–256. doi:10.1007/s12160-009-9111-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R. (2017). Black people don’t exercise in my neighborhood:Perceived racial composition and leisure-time physical activity among middle class blacks and whites. Social Science Research, 67, 42–57. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier M. F. Carver C. S. & Bridges M. W (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063–1078. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R. M., Caldwell C. H., Schmeelk-Cone K., & Zimmerman M. A (2003). Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servais M. (2010). Overview of HRS Public Data Files for Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analysis. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/index.php?p=famdat (Accessed March 15, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Smith J., Fisher G. G., Ryan L. H., Clarke P. J., House J., & Weir D. R (2013). Psychosocial and Lifestyle Questionnaire 2006 - 2010: Documentation Report.Ann Arbor: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/publications/biblio/8515 (Accessed March 15, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Stack C. B. (1974). All our kin: Strategies for survival in a black community. New York, NY: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Stack C. B., & Burton L. M (1993). Kinscripts. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 24, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal M. J., Slopen N., & Williams D. R (2011). Racial disparities in health: How much does stress really matter. DuBois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8, 95–113. doi:10.1017/S1742058X11000087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. J., Chatters L. M., & Levin J (2004). Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. J., Miller R., Mouzon D.M., Keith V., Chatters L.M. (2016, in press). “Everyday discrimination among African American men: The impact of criminal justice system contact.”Race and Justice. doi:10.1177/2153368716661849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. J. Mouzon D. M. Nguyen A. W. & Chatters L. M (2016). Reciprocal family, friendship and church support networks of African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Race and Social Problems, 8, 326–339. doi:10.1007/s12552-016-9186-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. A. (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51 Suppl, S41–S53. doi:10.1177/0022146510383499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. A. (2016). The impact of relationship-specific support and strain on depressive symptoms across the life course. Journal of Aging and Health, 28, 363–382. doi:10.1177/0898264315591004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe R. J., Duru O. K., & Hill C. V (2015). Advancing racial/ethnic minority men’s health using a life course approach. Ethnicity and Disease, 25, 241–244. doi:10.18865/ed.25.3.241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe R. J. Jr, & Halkitis P. N (2016). Biopsychosocial determinants of the health of boys and men across the lifespan. Behavioral Medicine (Washington, D.C.), 42, 129–131. doi:10.1080/08964289.2016.1191231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel W. M., Matthews K. A., Bromberger J. T., & Sutton-Tyrrell K (2003). Chronic stress burden, discrimination, and subclinical carotid artery disease in African American and Caucasian women. Health Psychology, 22(3), 300–309. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.3.300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner R. J. (2013). Understanding health disparities: The relevance of the stress process model. Society and Mental Health, 3, 170–186. doi:10.1177/2156869313488121 [Google Scholar]

- Turner R. J. Thomas C. S. & Brown T. H (2016). Childhood adversity and adult health: Evaluating intervening mechanisms. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 156, 114–124. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Thomeer M. B. Williams K. Thomas P. A. & Liu H (2016). Childhood adversity and men’s relationships in adulthood: Life course processes and racial disadvantage. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 902–913. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins D. C., Wharton T., Mitchell J. A., Matusko N., & Kales H. (2015, in press). Perceptions and receptivity of non-spousal family support: A mixed methods study of psychological distress among older, church-going African American men. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. doi:10.1177/1558689815622707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. (2009). The stress process as a successful paradigm. In Advances in the conceptualization of the stress process (pp. 231–252). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield K. E., Allaire J., Belue R., & Edwards C. L (2008). Are comparisons the answer to understanding behavioral aspects of aging in racial and ethnic groups?Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 63B, P301–P308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Yu Y., Jackson J. S., & Anderson N. B (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 335–351. doi:10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R. (2003). The health of men: Structured inequalities and opportunities. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 724–731. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.5.724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D., Costa M., & Leavell J (2010). Race and mental health: Patterns and challenges. In T. Scheid & T. Brown (Eds.), A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contexts, Theories, and Systems (pp. 268–290). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511984945.018 [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., & Mohammed S. A (2013). Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 1152–1173. doi:10.1177/0002764213487340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.