Abstract

Aim of the study

Interferon alpha-induced arthritis and activation of the type 1 interferon pathway during rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has been well documented but the underlying mechanism remains unclear. This study addressed the binding specificity of antibodies with recombinant interferon alpha 2b (rIFN α-2b) in sera from different RA patients. Utilization of anti-hrIFN α-2b antibodies as a probe for estimation of interferon α-2b concentration in RA patients’ synovial fluid (SF) was also investigated.

Material and methods

Binding specificities of antibodies from the sera of 60 RA patients and 35 controls subjects were studied by direct binding, inhibition ELISA, and quantitative precipitation titration. Inhibition ELISA was also used to estimate patients’ SF interferon α-2b concentrations.

Results

RA IgG from patients’ sera showed strong recognition to hrIFN α-2b in comparison to commercially available interferon (IFN α-2b) (p < 0.05) or the gene encoding this interferon (IFN α-2b gene) (p < 0.05). The affinity of RA antibodies for rIFN α-2b (1.10 × 10–7 M) was found to be high as assessed by Langmuir plot. No significant difference in the level of interferon α in the SF of RA patients was observed as compared to the healthy controls.

Conclusions

rIFN α-2b presents unique epitopes that might explain the possible antigenic role in the induction of RA antibodies and anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies represent an alternative immunological probe for the estimation of interferon α in the SF of RA patients.

Keywords: recombinant interferon alpha 2b (rIFN α-2b), RA, cloning, antibodies, ELISA

Introduction

Interferons are important cytokines that are secreted by leukocytes, fibroblasts, and lymphocytes. They can be used as targets for antiviral and anticancer treatments [1]. Interferons are glycoproteins that are classified into three major types based on properties such as antigenicity and biological and chemical traits. They include alpha (leukocytes), beta (fibroblasts), and gamma (immune). After the medical potential of interferons was recognized, the FDA approved the drugs, which primarily include recombinant α interferon 2a (Roferon A) and interferon α 2b (Intron A) for the treatment of malignant tumors and viral diseases [2, 3]. However, many autoimmune diseases (including RA) have been triggered following interferon therapy [4]. As an immune modulator, IFN-α can exacerbate autoimmune diseases. Earlier reports have demonstrated a relationship between IFN levels and disease activity in different RA patients [5]. Both IFN α and β have been detected in synovial fluids (SF) and tissues from these patients [6]. The role of IFN in RA is ambiguous. Genomic studies have shown a significant overexpression of type I IFN inducible genes in the peripheral blood from different RA patients [7]. Type I interferon gene expression has not been associated with clinical parameters, and an association between IFN levels and RA disease activity has not been shown [8]. In addition, IFN was anti-osteoclastogenic and inhibited osteoclast formation in RA [9]. IFN-α contributes to autoimmunity, not only in RA, but also in other types of diseases such as type 1 diabetes (DM), multiple sclerosis (MS), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [10].

Interferons have multiple effects on the immune system, which may contribute to the development of autoimmunity and disease progression in multiple autoimmune diseases. IFN α-induced effects may increase various autoimmune diseases, which includes increased production of immunoglobulins, inhibition of T-suppressor cell function, activation of cytotoxic T-cell functions, activation of large granular lymphocytes, and activation of monocytes/macrophages to secrete cytokines, prostaglandin, leukotrienes, and various other compounds involved in inflammation [11–17]. Autoimmune phenomena (especially RA) have developed in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection following IFN-α therapy [18]. These patients were positive for anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies [16]. Although RA is one of the most common autoimmune diseases induced/exacerbated by IFN α-2b therapy [19], the main focus was primarily given to other autoimmune diseases.

In this study, we investigated the binding affinity of the RA autoantibodies with recombinant human interferon alpha 2b (rIFN α-2b), IFN α-2b, and the IFN α-2b gene. The target DNA fragments were first cloned and expressed in the prokaryotic Escherichia coli strain, BL21. The recombinant protein, rIFN α-2b, was also used as a triggering antigen to induce antibodies that can be used to estimate IFN-α concentrations in the SF from RA patients. We also evaluated the characteristics and binding properties of induced antibodies against rIFN α-2b and IFNα-2b.

Material and methods

Patients and controls

Study RA patients were diagnosed according to the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria [20]. Blood was collected from RA patients (n = 60). Patients included three 3 males and 57 females (ages 63 ±7 and 67 ±4 years, respectively) admitted to the district hospital. Thirt-five healthy subjects (2 males and 33 females, ages 60 ±8 and 58 ±7 years, respectively), who were employees of the same hospital, served as control subjects. None of the control subjects had any history of illness (viral or any other disease), which was confirmed by a physician. At the time of admission, all patients were receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, various disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, or both. All serum samples were heated at 56°C for 30 min to inactivate complement protein and stored at –20°C with 0.2% sodium azide. Serum samples were centrifuged at 1,500 g for 10 min before being treated with heat to inactivate complement protein. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Centre and informed consent was obtained from each subject. For IFN-α estimation, cell free SF was obtained from ten patients (RA, n = 10) and 10 controls and were stored at –20°C until analysis. SF samples were collected into tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and kept at –20°C. Before assaying the samples, SF was digested with hyaluronidase (30 U/ml, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 37°C for 30 min to reduce viscosity and then centrifuged at 4°C for 1 min at 8050 g to collect supernatant.

Bacterial strains, vectors and primers

Escherichia coli strain DH5α, BL 21(DE3), and cloning vectors pET28a, pET32a, and pTZ57R/T were obtained from Invitrogen, USA, Novagen, USA, and Fermentas, USA, respectively. Primers were either selected from the available literature or designed using Primer 3 software supported by manual calculations and finally verified for specificity using the National Centre for Biotechnology Information BLAST server. Oligoes (in lyophilized form) and IFN α-2b were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. DNA isolation kits were obtained from Gentra systems and all the restriction digestion enzymes (BamHI, EcoR1, Ndel) were purchased from Sigma.

Isolation of genomic DNA from human leukocytes

DNA was isolated using either the DNA Purification from Buffy Coat protocol (Gentra Systems) with several modifications or the phenol chloroform method by Sambrook et al. [21].

Amplification and cloning of human interferon alpha 2b gene into expression vector

A 520-bp fragment coding for human IFN 2b was amplified from human genomic DNA using PCR technology with a forward primer: 5’TTGAATTCATATGTGTGATCTGCCTCAAACCCACAGC-3’and reverse primer:5’-CCTAGGTAATAAGGAAGAAGAATTTGAAAGAACG-3’ [22]. The amplified DNA fragment was restricted and cloned into BamHI/EcoRI-digested pUC19. Subsequently, the hu-IFN-2b fragment was cut from pUC-IFNα and cloned into a BamHI/NdeI-digested pET-32a expression vector.

The amplified fragment (520bp) was double digested and cloned into BamHI/EcoRI-digested cloning vector pTZ57R. Subsequently, the cloned DNA fragment was cut from pTZ57R/T-IFN and subcloned into a BamHI/NdeI-digested pET 28a expression vector (Invitrogen). The ligation mix was then introduced into DH5 alpha competent cells, and the recombinant clones were screened by colony using the IFN gene specific primers. The PCR positive clones were later selected by restriction digestion, and the selected clone was designated as pET28a-IFN.

The cloned recombinant DNA constructs (prepared previously) were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells. A 200 μl aliquot of chemically-competent cells was thawed on ice in 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes. Approximately 30 ng plasmid DNA was added to 200 μl of competent cells and mixed gently. The cells were incubated on ice for 30 min, heat shocked at 42°C for 45 s, and subsequently incubated on ice for 5 min. One milliliter of LB medium was added to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 1 h at 4 g. A 200 μl aliquot of the transformation mixture was plated on a pre-warmed LB agar containing the appropriate antibiotic. The inverted plate was incubated overnight at 37°C. The transformants (colonies) were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and Xgal (40 μg/ml). The transformants were named E. coli: JW1.

Expression and purification of recombinant human interferon α-2b protein

For expression experiments, constructs were transformed into E. coli host BL21 (DE3) as described above. Strains harboring relevant constructed recombinant plasmids were recovered from frozen (–70°C) glycerol stocks by streaking onto LB-agar plates containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and incubated at 37°C overnight. Subsequently, a single colony was transferred to LB liquid medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin in 10 ml Falcon tubes and were grown for 2–3 h in a 37°C shaking water bath 4 g until the optical density (OD) reached 0.5–0.6. The freshly grown culture in 250 ml (0.5–0.8%) was taken and induced expression by the addition of auto-induction medium for overnight at 37°C as described by Studier [23]. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1280 g at 4°C for further use.

The constructed recombinant proteins expressed in E. coli were purified using TALON affinity chromatography (Clontech, USA). Fifty milliliters of bacterial culture were incubated with lysozyme (100 μg/ml) with 5 ml of buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl). The suspension was sonicated and centrifuged at 1280 g for 10 min at 4°C in order to separate the supernatant as a soluble protein with the pellet. Further centrifugation at 2010 g in 5 ml of resuspension buffer for 10 min at 4°C separated the supernatant with cell debris. The supernatant was incubated with the TALON resin for 1 hr at 4°C followed by the upload of the sample into the column. The column was washed twice with 10 ml of washing buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl and 6 M GndCl) and proteins were eluted with 4 ml of elution buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. Protein samples were loaded using SDS-PAGE to check the expression of recombinant human interferon α-2b (rIFN α-2b) [24].

Antibodies against recombinant interferon α-2b and commercially available interferon

Antibodies against the respective antigens (rIFN α-2b and IFN α-2b), along with suitable controls, were induced in experimental animals (female rabbits, random bred, New Zealand White, 5n) as described previously [25]. Briefly, antigens (50 μg) were emulsified with an equal volume of complete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich) and injected intramuscularly into female rabbits. Subsequent injections were given in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant. Each animal received a total of 400 μg of antigen that was administered weekly for eight weeks. Blood was collected from the marginal vein of the ear. Preimmune serum was collected prior to immunization. The sera were stored in small aliquots at –20°C with 0.1% sodium azide as preservative.

Purification of immunized immunoglobulin G

Using a protein A-agarose column (Sigma), immunoglobulin G was isolated from the sera of RA patients/immunized animals. The homogeneity of isolated IgG was confirmed on 7.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis PAGE [26].

ELISA

A direct binding ELISA was performed for antibody screening in the sera from RA patients/immunized animals [26]. Competition ELISA was performed to determine the specific binding of RA/immunized antibodies to rIFNα-2b and IFN α-2b [27]. Briefly, 100 μl of an antigen aliquot (rIFN α-2b or IFN α-2b; 2.5 μg/ml) were coated onto microtiter plates, incubated for 2 hr at room temperature, and overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed with TBS-T (50 mM Tris, 150 m NaCl, and 0.05 Tween 20, pH 7.6) and blocked with 150 μl of 1.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Immune complexes were prepared by mixing 100 μl of a 1 : 100 serum dilution with increasing amounts (0–20 μg/ml) of respective antigens and incubated initially at 37°C for 2 h and overnight at 4°C. One hundred microliters of the immune complex was added to each well, followed by anti-human IgG-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Sigma-Aldrich). The reaction was developed with p-nitrophenyl phosphate as substrate (Sigma), and absorbance was recorded at 410 nm on a micro plate reader (Labsystem Multiskan EX, Helsinki, Finland).

Formation and quantitation of immune complexes

Formation and quantitation of immune complexes have been done as described earlier [28]. Briefly, one hundred micrograms of IgG were incubated with varying amounts of different interferons in an assay volume of 500 μl. Normal IgG served as control. The mixture was incubated for 2 h at room temperature and overnight at 4°C. The immune complex was pelleted, washed twice with PBS, and dissolved in 250 μl 1N NaCl. Free protein and complex-bound proteins were measured by colorimetric methods [29]. The binding data were analyzed for antibody affinity [30].

Statistical analysis

Significance of difference from control values was determined with the Student’s t-test (IBM SPSS, Statistic 22). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The values are presented as mean ±SD wherever indicated.

Results

Genomic DNA and human interferon α-2b gene fragment

The purity of blood-based DNA was confirmed with gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry. Only a single DNA band was observed on the agarose gel (data not shown). It is clear that all the extracted DNAs were of high quality with no smear formation. In addition, the ratio of absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm (A260/A280) was 1.8 showing the purity of isolated DNA.

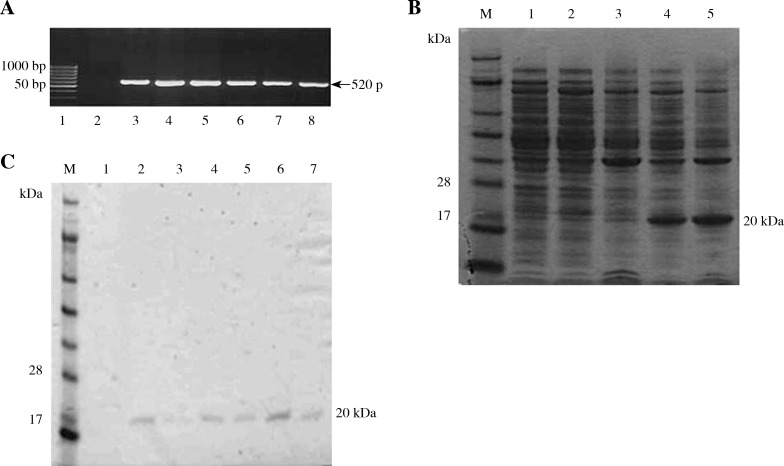

The extracted DNA samples from randomly selected blood samples were used as a template to amplify the INF α-2b gene using forward and reverse primers as described earlier (see: Material and methods). The PCR conditions were optimized with respect to annealing temperature, template concentration, MgCl2, and extension time. Figure 1A presents an analysis of PCR-amplified products of the INF α-2b gene fragment from the genomic DNA extracted from blood samples in conjunction with negative and positive controls and a 50 bp DNA marker. As expected, the PCR process resulted in the formation of 520 bp. No amplification was observed in the negative control. All of the amplified PCR DNA fragments were cloned in the expression vector pET28a. The constructed recombinant plasmid was transformed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. The transformants (white colonies) were selected as blue/white colonies on the LB agar plate supplemented with antibiotics. Recombinant plasmids containing the amplified DNA were isolated from the transformants. Finally, the construct was confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Gel electrophoresis of human 2b alpha interferon gene, interferon alpha 2b protein and purified interferon alpha 2b. A) Analysis of amplified PCR product of human 2b alpha interferon gene from different genomic DNA isolates. Lane 1: 50 bp DNA ladder (MBI, Fermentas). Lane 2: Negative control. Lanes 3-8: amplified product of human 2b alpha gene (520 bp). B) Expression and purification analysis for proteins. Lane M: Protein marker, Lane 1: BL21 (supernatant), Lane 2-3: BL21(DE3)+pET28a (Supernatant and pellet) respectively, Lane 4-5: JW-1(Supernatant and pellet). C) Purified expressed proteins by talon affinity chromatography. Lane M: Protein marker, Lane 1: Negative control, Lane 2-7: Purified protein (20 kDa)

Expression of recombinant protein

To examine the expression of recombinant DNA constructs, the engineered E. coli strain (E. coli JW1) harboring respective constructs were grown overnight in minimal media containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and induced by lactose/glucose. The bacterial cells were harvested, lysed, and fractionated into supernatant and inclusion bodies (formed as cells) using chromatographic methods.

SDS-PAGE was used to examine the protein profile of transformed E. coli strain containing the constructs and the E. coli strain without constructs. Figure 1B shows the generation of new protein bands (Fig. 1B, lanes 4 and 5); these protein bands were absent from BL21 or BL21(DE3)+pET28a (Fig. 1B, lanes 1–3). The lysed proteins from the transformed E. coli cells (recombinants harboring construct), non-transformed E. coli, and E. coli cells plus vector pET28a were fractionated into soluble supernatant and pellet. The recombinant protein from the transformed bacterial strains (JW1) was highly expressed in pellet fractions when compared with the soluble fractions (Fig. 1B, lanes 4 and 5). The expressed proteins were further purified by the TALON affinity chromatography. There was exactly one 20 kDa band (Fig. 1C, lanes 5–10).

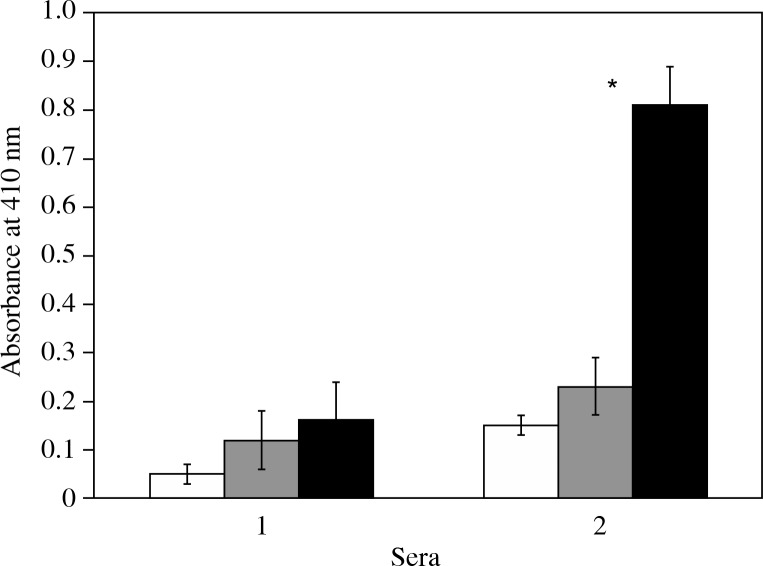

Detection of anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies in the sera of RA patients

RA sera from different patients were screened for the presence of antibodies against rIFN α-2b, IFN α-2b, and IFN α-2b genes by direct binding ELISA. Almost all of the sera showed higher recognition of rIFN α-2b than IFN α-2b (p < 0.05) or IFN α-2b gene (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Direct binding ELISA of controls and RA patients.Direct binding enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of control (1, n = 35) and RA antibodies (2, n = 40) to rIFN α-2b (◻), IFN α-2b (◻) and IFN α-2b gene (◼). Microtitre plates were coated with 2.5 μg/ml of the respective antigen. The reaction was developed with p-nitrophenyl phosphate as the substrate and the absorbance was recorded at 410 nm as described in Material and Methods. Absorbance at 410 nm can be used to measure binding of IgG with different interferons. Each histogram represents the mean±SD. Significantly higher than control (#p < 0.001) and IFN α-2b (p < 0.05) and IFN α-2b gene (p < 0.05)

No appreciable binding was observed in the sera of healthy subjects. Binding specificity was also checked with IFN α-2b. Their binding is low in comparison to the rIFN α-2b. IFN α-2b genes do not show any specificity with RA or control antibodies.

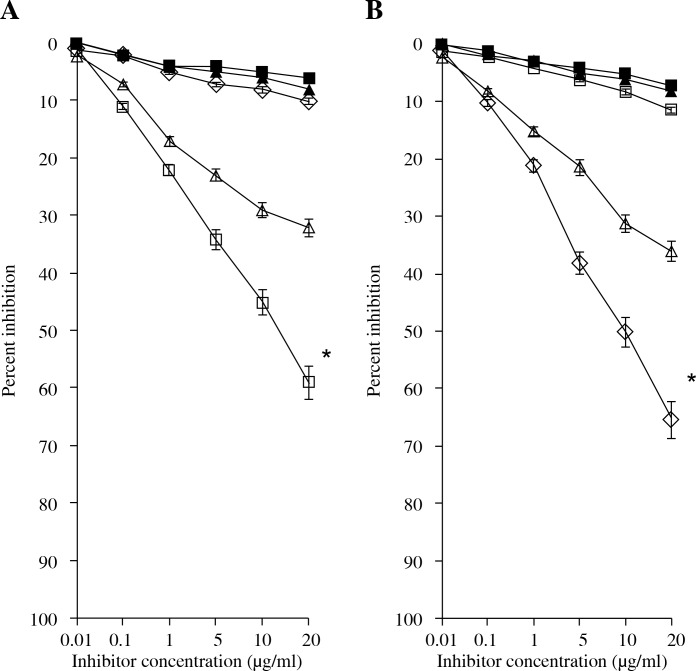

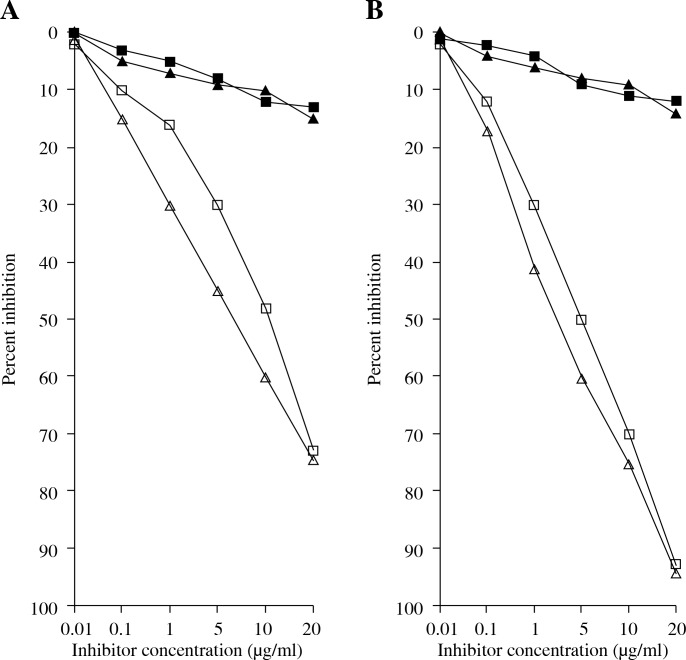

Specific recognition of RA antibodies by rIFN α-2b, IFN α-2b, and IFN α-2b genes was also ascertained by competitive-inhibition ELISA. The rIFN α-2b had an inhibition of 58.3 ±8.1% (43.1-70.2%) in 60 RA sera, while the IFN α-2b and IFN α-2b genes showed a lower inhibition ranging from 15.8% to 53.3% (32.1 ±6.5%) for IFN α-2b and 2.5% to 16.1% (8.4 ±4.1%) for the IFN α-2b gene (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition ELISA of control and RA patients. A) Inhibition ELISA of anti-(rIFN α-2b, IFN α-2b, IFN α-2b gene) RA (◻, Δ, ◊) and Control (◼, ▲) sera with rIFN α-2b, IFN α-2b, IFN α-2b gene. B) Inhibition of RA anti-(rIFN α-2b, IFN α-2b, IFN α-2b gene) IgG binding to rIFN α-2b (◊), IFN α-2b (Δ), IFN α-2b gene (◻). (▲, ◼) Represent the inhibition of normal anti-rIFN α-2b and IFN α-2b IgG binding to rIFN α-2b and IFN α-2b. Microtitre plates were coated with respective antigens (2.5 μg/ml). Immune complexes were prepared by mixing 100 ml of 1 : 100 dilution of serum antibodies from RA patients and control individuals with the increasing amount (0-20 mg/ml) of respective interferons at 37°C. Note: Inhibition values for control sera and IgG with IFN α-2b gene were negligible and are not shown.

*Significantly higher inhibition than IFN α-2b (p < 0.05) and IFN α-2b gene (p < 0.001)

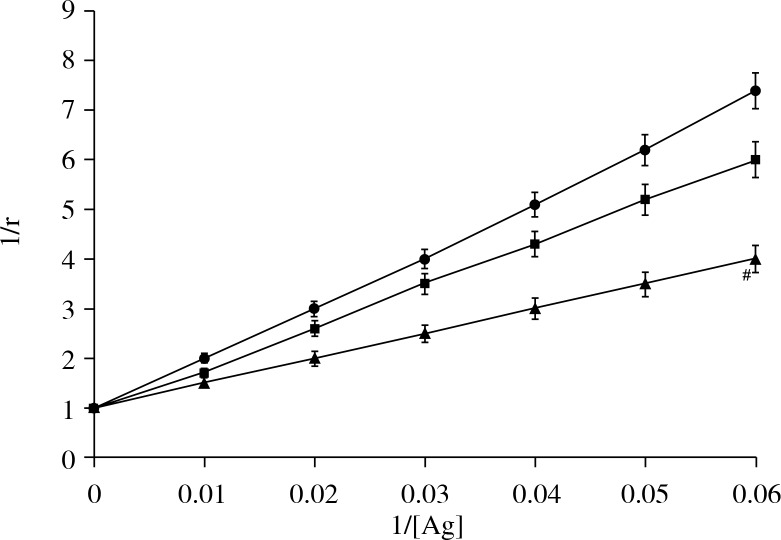

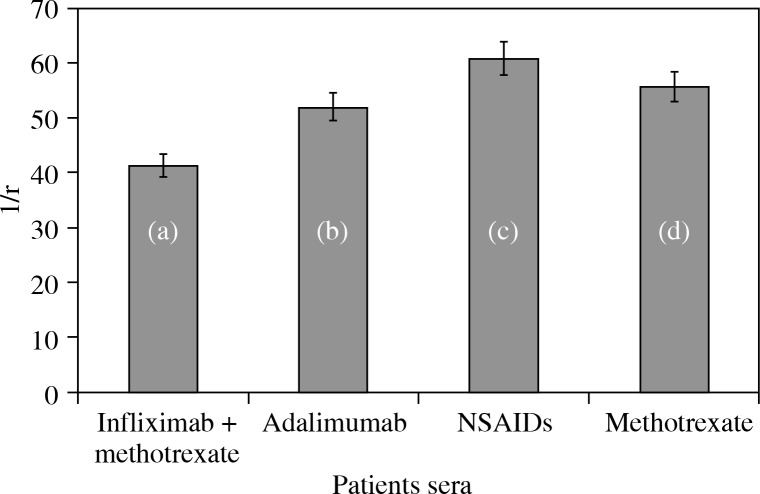

RA IgG was purified by affinity chromatography on protein A-agarose columns. Purified IgG eluted as a single symmetrical peak on SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions showed a single homogenous band (data not shown). In competitive inhibition assays, the RA IgG showed inhibition ranging from 50.1% to 80.1% (average 65.3 ±8.2%) for rIFN α-2b. IFN α-2b showed an inhibition of RA IgG ranging from 25.3% to 58.5% (average 35.3 ±6.5%) (Fig. 3b). Again, the IFN α-2b gene showed a negligible inhibition ranging from 3.8% to 15.3% (average 12.1 ±3.4%). The antigen-antibody interaction was also characterized by quantitative precipitation titration. Increasing amounts of interferons and their respective genes (rIFN α-2b, IFN α-2 band, and IFN α-2b gene) were added to 100 μg of RA IgG (n = 15). Normal IgG was the negative control. The results showed that 24 μg of rIFN α-2b was bound to 73 μg of RA IgG. With IFN α-2b, 39 μg of IFN α-2b was bound to approximately 59 μg of RA IgG. With the IFN α-2b gene, a maximum of 49 μg of antigen was bound to 51 μg of RA IgG. Langmuir plots were used to evaluate the apparent association constants (Fig. 4). The constants were computed to be 1.10 × 10-7 M, 1.41 × 10-6 M, and 1.31 × 10-6 M for rIFN α-2b, IFN α-2b, and the IFN α-2b gene, respectively. The binding affinity was also verified according to the use of anti-TNF therapy or any other drugs taken during the course of the study. We have divided 15 patients’ sera into groups, which were further divided into those patients that were taking methotrexate, NSAIDS, infliximab + methotrexate, and adalimumab. It was found that the binding of rIFN α-2b with the patients’ sera who have been taking infliximab + methotrexate was 41.3%, which was the lowest among all of the groups. The binding of the other group with rIFN α-2b was adalimumab (52.1%), NSAIDS (61%), and methotrexate (55.8%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Determination of an apparent association constant by Langmuir plot. Antigens were rIFN α-2b (▲), IFN α-2b (◼) and cIFN α-2b gene (●). Immune complexes were prepared by incubating 100 mg of IgG with varying amount of different interferons (0-100 mg) in an assay volume of 500 ml for 2 h at room temperature and overnight at 4°C. The binding data were analyzed for antibody affinity as described in Material and methods. #Significantly higher binding than IFN α-2b (p < 0.05) and IFN α-2b gene (p < 0.001)

Fig. 5.

Binding of RA patients’ IgG with rIFN α-2b from the patients who have taken (a) infliximab + methotrexate, (b) adalimumab, (c) NSAIDS and (d) methotrexate. Microtitre plates were coated with 2.5 μg/ml of the respective antigen and the values are corrected in terms of percent binding

Antibodies production and their characterization

The antigenicity of different antigens (rIFN α-2b and IFN α-2b) was also determined by inducing antibody production in rabbits against these antigens. The antigenic specificity of the induced antibodies was assayed by direct binding and competitive ELISAs. The direct binding ELISA was used to characterize the immune response in rabbits following immunization with rIFN α-2b and IFN α-2b. The rIFN α-2b was highly immunogenic. Antisera showed high titer antibodies (≥ 1 : 25,600) in the direct binding ELISA. Pre-immune serum served as the negative control and did not show any appreciable binding to rIFN α-2b. After immunization with IFN α-2b, the antiserum showed nearly the same binding as the antigen. The titer shown by IFN α-2b was similar (but low) in comparison to rIFN α-2b.

The competitive ELISA further validated the specificity of the induced antibodies. A maximum of 74.5% inhibition in antibody activity was obtained at a rIFN α-2b concentration of 20 μg/ml. The concentration of immunogen (rIFN α-2b) required for 50% inhibition was 8.8 μg/ml (Fig. 6A). For INF α-2b, a maximum of 72.8% antibody inhibition was obtained at an immunogen concentration of 20 μg/ml; 50% inhibition was achieved at 12.8 μg/ml of immunogen (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Inhibition ELISA of immunized interferons. A) Inhibition ELISA of anti-(rIFN-α2b, IFN-α2b,) immune (Δ, ◻) and preimmune (◼, ▲) sera with rIFNα-2b, IFN α-2b. B) Inhibition of immune anti-(rIFNα-2b, IFN α-2b) IgG binding to rIFN-α2b (Δ), IFN-α2b (◻). (◼, ▲) represent the inhibition of pre-immune anti-rIFN-α2b and IFN-α2bIgG binding to rIFN-α2b and IFN-α2b. The experiments were carried out by incubating the ELISA plate with 100 (l of respective antigens (2.5 μg/ml) as described in Material and methods

IgG was isolated from pre-immune and immune rabbit sera by affinity chromatography on a protein A-agarose column. The IgG purity was evaluated by SDS-PAGE in the absence of a reducing agent. The purified IgG migrated as a single band upon electrophoresis, and direct binding ELISA of these IgG samples showed strong recognition of rIFN α-2b. Pre-immune IgG served as a negative control with negligible binding. The specificity of purified IgG was also evaluated by competition inhibition assays. In the competition ELISA, the anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies showed a strong preference for the immunogen (rIFN α-2b) causing 94% inhibition in antibody binding at 20 μg/ml of the immunogen (competitor concentration). Fifty percent inhibition was observed at only 2.75 μg/ml of the immunogen (Fig. 6B). For IFN α-2b, a maximum of 92.8% inhibition in antibody binding was observed with the immunogen as the inhibitor. The concentration required for 50% inhibition was 5.5% μg/ml.

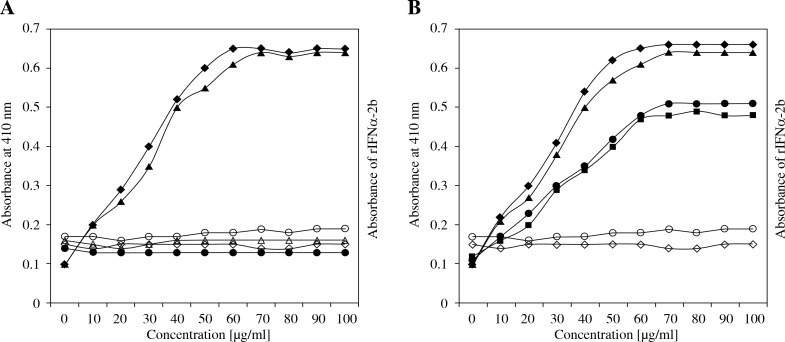

The antigenic specificity of the induced antibodies (against rIFN α-2b and INF α-2b) was characterized by competitive inhibition assay using IFN-β, IFN-ω, IFN-γ, and IFN-λ as inhibitors. The anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies demonstrated very low degrees of binding toward all of the other interferons except rIFN α-2b and IFN α-2b in which the inhibition values were quite high (Fig. 7A). In contrast, anti-IFN α-2b antibodies showed a high degree of binding toward rIFN α-2b followed by IFN-β and IFN-γ (Fig. 7B). There was very little inhibition with IFN-ω and IFN-λ other than to its own antigen.

Fig. 7.

IummnoImmune cross-reactivity of immunized IgG with different interferon. Estimation of immune cross-reactivity (A) anti-rIFNα-2b antibodies against rIFNα-2b (◆ ), IFN α-2b (▲ ), IFN β ( ○), IFN ω (Δ), IFN γ (◊), IFN λ ( Δ) (B) anti-IFN α-2b antibodies against IFN α-2b (◆ ), rIFNα-2b (▲ ), IFN β (● ), IFN γ (◼ ), IFN ω (○)), IFN λ (◊). Immune cross-reactivity was calculated by incubating the ELISA plate with the respective interferon (100 ml, 2.5 mg/ml) and absorbance was recorded at 410 nm

Immune cross-reactivity of anti-rIFN α-2b and antiIFN α-2b antibodies toward IFN α-2b and rIFN α-2b, respectively, allows us to use anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies as a probe to estimate IFN α in the SF from RA patients. INF α levels in SF as estimated by anti-rINF α-2b antibodies, was further confirmed by Interferon α ELISA Kits (Bender Med SystemsTM, San Bruno, CA, USA). The level of interferon α-2b, as estimated by anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies, was 150.8 ±3.1 pg/ml, which is comparable to the data obtained by using Interferon α ELISA Kits (150.1 ±4.8 pg/ml) (r = 0.98, p < 0.001). In healthy individuals (n = 10), the mean interferon α-2b was 145.3 ±5.1 pg/ml (Table 1). No significant differences in INF α levels in the SF from RA patients was observed when compared with healthy controls.

Table 1.

Clinical data and estimation of interferon α by anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies in different RA patients

| Factor | RA patients (n = 60) | Control (n = 35) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66 ±5 | 50 ±3 | |||

| No. of men/no. of women | 3/57 | 2/33 | |||

| Disease duration (years) | 8.8 ±4.1 | – | |||

| CRP level, mg/dl | 4.1 ±1.8* | – | |||

| ESR | 42 ±3.9* | – | |||

| SF nuclear cells | 19110 ±3998* | – | |||

| SF protein (g/l) | 45.5 ±2.9* | – | |||

| WBC count, × 103/l | 9.1 ±3.5* | – | |||

| Rheumatoid factor positive (%) | 72 | – | |||

| Anti-CCP positive (%) | 68 | – | |||

| Methotrexate dose mg/week (mean) (n = 50) | 11.86 | – | |||

| Use of NSAIDs (%) | 61 | – | |||

| Infliximab (3 mg/kg) in combination with methotrexate (n) | 45 | – | |||

| Adalimumab 40 mg/every other week (n) | 16 | – | |||

| #Interferon α estimation in SF (n = 10) by: | |||||

| Anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies | 150.8 ±3.1 pg/ml$ | 145.3 ±5.1 pg/mla | |||

| Interferon α ELISA antibodies | 150.1 ±4.8 pg/ml | ||||

The amount of SF interferon α level was measured by ELISA and the values are presented as mean ±SD, an = 10

ESR – erythrocytes sedimentation rate, CRP – C reactive protein, SF – synovial fluid, WBC – white blood count

RA vs. normal subjects p < 0.05 (Student’s t-test)

Correlation coefficient r = 0.98 (p < 0.001)

Discussion

INF α constitutes a group of proteins known for their antiviral, antiproliferative, antibacterial, and immunomodulating activity. They are important therapeutic proteins that can be used as targets for the treatment of various diseases such as hepatitis B and C and several types of cancer. These are the most widely used members of the interferon family. They exert many biological actions including broad-spectrum antiviral effects, inhibition of tumor cell proliferation, and enhancement of immune function [31, 32]. Recombinant interferon therapy has been widely used to treat chronic viral hepatitis and several different malignancies. These therapies not only improve the prognosis of many malignancies, but also have been associated with some unexpected side effects, the most important of which is the development of antibodies against it.

It is well known that various autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, vitiligo, autoimmune thyroid disease, autoimmune thrombocytopenia, antiphospholipid syndrome, polymyositis, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune hepatitis, and rheumatoid arthritis [33–41], can be triggered following IFN therapy. In addition, studies have also demonstrated that the development of autoantibodies or clinical manifestations of autoimmunity during adjuvant high-dose IFN treatment can lead to RA [41].

Naturally occurring autoantibodies to recombinant interferon α-2b have been discovered in various healthy blood donors [42]. RA can be linked to interferon based on the relationship between interferon levels and disease activity [5], although the role of IFN in RA is obscure. Some studies have shown an association between IFN levels and RA activity while others do not. Interferon α has been detected in the synovial fluid and tissues in different RA patients with a significant overexpression of type I IFN inducible gene in the peripheral blood of these patients [6, 7]. There are no evident associations between the peripheral IFN signature in established RA and clinical parameters [8]. This would suggest that IFN is not an indication of disease activity. However, its immunomodulatory properties in RA may cause various other autoimmune manifestations. This cannot be explained unless the specificity and binding properties of anti-RA antibodies are investigated. To explain this important aspect, which has been neglected for over three decades, the binding of RA antibodies with rIFN α-2b, IFN α-2b, and the IFN α-2b gene was examined to check multiple antibody specificity in RA. The binding specificities of antibodies from the sera of 60 RA and 35 normal subjects to rIFN α-2b, IFN α-2b, and the IFN α-2b gene were confirmed by direct binding, inhibition ELISA, and quantitative precipitation titration. rIFN α-2b showed higher binding with RA sera in comparison to IFN α-2b (p < 0.05) and the IFN α-2b gene (p < 0.05). These results showed that rIFN α-2b is an effective inhibitor with substantial differences in the recognition of rIFN α-2b over IFN α-2b or the IFN α-2b gene by RA antibodies. Therefore, RA antibodies preferably recognized rIFN α-2b epitopes over IFN α-2b or the IFN α-2b gene. Similar types of antibodies have been previously used to treat various RA patients [43].

Finally, the interferon-antibody interaction was characterized by a quantitative precipitation titration, and the affinity of RA antibodies toward rINF α-2b was found to be higher with an affinity constant of 1.10 × 10-7 M. However, for INF α-2b, the computed constant was 1.41 × 10-6 M. This showed less affinity in comparison to rINF α-2b. As far as the INF α-2b genes are concerned, the antibodies had a lower affinity with this gene. Higher recognition of rIFN α-2b by RA antibodies demonstrated the possible antigenic role of rIFN α-2b in RA. Therefore, rIFN α-2b might generate discriminating epitopes that have been effectively recognized by RA antibodies. rIFN α-2b binding in different groups showed that sera of the patients with infliximab + methotrexate interfered with the binding of rIFN α-2b in this group. This might be due to the presence of already existing IgG in these patients, which might inhibit binding. All of the other groups showed slightly higher binding, indicating less inhibition in binding of rIFN α-2b with their IgGs.

Immune cross-reactivity experiments have been done in order to understand whether the epitopes on the antigens (rIFN α-2b and IFN α-2b) are unique enough to be recognized by the induced antibodies or if common paratopes are shared with other induced antibodies. The data clearly showed that anti-rINF α-2b antibodies recognize not only the unique epitopes on rIFN α-2b, but also show cross-reactivity with IFN α-2b. Similarly, in IFN α-2b, the anti-IFN α-2b antibodies showed a high degree of binding towards rINF α-2b. This showed that the epitopes on rIFN α-2b were highly recognized by anti-IFN α-2b antibodies in addition to other interferons. The results of these experiments agree with previous studies in which the generation of various types of immune cross-reactive antibodies after IFN-α therapy was shown [44]. Because of the cross reactivity shown by anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies with IFN α-2b, these antibodies can be used as a probe to estimate the INF-α concentrations in SF from RA patients. The data clearly demonstrated that anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies can be effectively used as a probe for interferon α estimation in different RA patients.

We have attempted to describe the possible antigenic role of rIFN α-2b in the production of antibodies in RA. rIFN α-2b generates discriminating epitopes that are efficiently recognized by RA antibodies. In addition, we also considered INF α-2b immune regulatory function that somehow produces antibodies that can recognize this interferon. Anti-rIFN α-2b antibodies are an alternative immunochemical probe for the estimation of INF-α in the SF of RA patients. This study demonstrates the possible role of rIFN α-2b in presenting unique neo-epitopes that may be one of the factors in the induction of RA antibodies.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grant (No.: 246) from the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Khalid University, Abha, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Technical help during cloning experiment by Dr. Javed was highly appreciated.

Footnotes

The authors declares no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Gray PW, Goeddel DV. Structure of the human immune interferon gene. Nature. 1982;298:859–863. doi: 10.1038/298859a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus Infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, et al. Interferon-Alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:289–296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gogas H, Ioannovich J, Dafni U, et al. Prognostic Significance of Autoimmunity during Treatment of Melanoma with Interferon. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:709–718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacon TH, deVere-Tyndall A, Tyrell DAJ, et al. Interferon system in patients with systemic juvenile chronic arthritis in vivo and in vitro studies. Clin Exper Immunol. 1983;54:23–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conigliaro P, Perricone C, Benson RA, et al. The type I IFN system in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmunity. 2010;43:220–225. doi: 10.3109/08916930903510914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.vander Pouw Kraon TC, Wijbrandts CA, van Barsen LG, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis subtypes indentified by genomic profiling of peripheral blood cells: assignment of a type I interferon signature in a subpopulation of patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1008–19. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.063412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Jong TD, Blits M, de Ridder S, et al. Type I interferon response gene expression in established rheumatoid arthritis is not associated with clinical parameters. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:290. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-1191-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung SM, Kim KW, Yang CW, et al. Cytokine-mediated bone destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol Res. 2014;263625:15. doi: 10.1155/2014/263625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crow MK. Type I interferon in organ-targeted autoimmune and inflammatory disease. Arth Res Ther. 2010;12:S5. doi: 10.1186/ar2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun W, Levy HB. Interferon preparations as modifiers of immune responses. Proc Soc Exper Biol Med. 1972;141:769–773. doi: 10.3181/00379727-141-36868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gisler RH, Lindahl P, Gresser I. Effects of interferon on antibody synthesis in vitro. J Immunol. 1974;113:438–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levinson AI, Dziarski A, Hooks JJ. Modulation of polyclonal B cell differentiation byhuman leukocyte alpha interferon. Clin Exper Imunol. 1982;49:677–683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chester TJ, Paucker K, Merigan TC. Suppression of mouse antibody producing spleencells by various interferon preparations. Nature. 1973;246:192–194. doi: 10.1038/246092a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brodeur BR, Merigan TC. Mechanism of the suppressive effectof interferon on antibody synthesisin vivo. J Immunol. 1975;114:1323–1328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borden EC, Ball LA. Interferons: Biochemical cell growth inhibitory and immunological effects. Prog Hematol. 1981;12:299–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heron I, Berg K, Cantell K. Regulatory effect of interferon on T cells in vitro. J Immunol. 1976;117:1370–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cacopardo B, Benauti F, Pinzone MR, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis following PEG-interferon alpha-2a plus ribavirin treatment for chronic hepatitis C: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:437. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izumi Y, Kamari A, Yasunaga Y, et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis following a treatment with IFN-alpha/ribavirin against HCV infection. Inter Med. 2011;50:1065–1068. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arth Rheumatol. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. 2nd. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual; p. 1659. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valente CA, Prazeres DMF, Cabral JMS, et al. Translational Features of Human Alpha 2b Interferon Production in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:5033–5036. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.8.5033-5036.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking culture. Prot Exper Purif. 2005;41:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan WA, Qureshi JA. Increased binding of circulating systemic lupus erythematosus autoantibodies to recombinant interferon alpha 2b. APMIS. 2015;123:1016–1024. doi: 10.1111/apm.12464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dixit K, Ali R. Role nitric oxide modified DNA in the etiopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2004;13:5–100. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu492oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan WA, Alam K, Moinuddin Catecholestrogen modified DNA: A better antigen for cancer autoantibody. Arch Biochem Biophy. 2007;465:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan WA, Habib S, Khan MWA, et al. Enhanced binding of circulating SLE autoantibodies to catecholestrogen-copper-modified DNA. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;315:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9798-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;315:143–150. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langumir I. The adsorption of gas on plane surface glass, mica and platinum. J Am Chem Soc. 1918;40:1361–1403. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di B, Martin P, Lisker-Melman M, Kassianides C, et al. Therapy of chronic delta hepatitis with interferon alpha-2b. J Hepatol. 1990;11:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90185-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romerio F, Zella D. MEK and ERK inhibitors enhance the antiproliferative effect of interferon-α2b. FASEB J. 2002;16:1680–1682. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0120fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trefzer U, Hofmann M, Sterry W. Cutaneous side effects of clinically relevant cytokines therapies. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2003;128:1782–1787. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guillot B, Blazquez L, Bessis D, et al. A prospective study of cutaneous adverse events induced by low-dose alpha-interferon treatment for malignant melanoma. Dermatol. 2004;208:49–54. doi: 10.1159/000075046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandac JC, Chaudhry S, Sherman KE, et al. The clinical and physiological spectrum of interferon-alpha induced thyroiditis: toward a new classification. Hepatol. 2006;43:661–672. doi: 10.1002/hep.21146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dourak SP, Deutsch M, Hadziyyanis SJ. Immune thrombocytopenia and alpha-interferon therapy. J Hepatol. 1996;25:972–975. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Becker JC, Winkler B, Klingert S, et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome associated with immunotherapy for patients with melanoma. Cancer. 1994;73:1621–1624. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940315)73:6<1621::aid-cncr2820730613>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalkner KM, Ronnblom L, Karlsson PA, et al. Antibodies against double-stranded DNA and development of polymyositis during treatment with interferon. QJM. 1998;91:393–399. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.6.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Betterle C, Fabris P, Zanchetta R, et al. Autoimmunity against pancreatic islets and other tissues before and after interferon-alpha therapy in patients with hepatitis C virus chronic infection. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1177–1181. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.8.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dumouhi FL, Leifeld L, Sauerbruch T, et al. Autoimmunity induced by interferon-alpha therapy for chronic viral hepatitis. Biomed Pharmaco. 1999;53:242–254. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(99)80095-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gogas H, Ioannovich J, Dafni U, et al. Prognostic Significance of Autoimmunity during Treatment of Melanoma with Interferon. New Engl J Med. 2006;354:709–718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross C, Hansen MB, Schyberg T, et al. Autoantibodies to crude human leucocyte interferon (IFN), native human IFN, recombinant human IFN-alpha 2b and human IFN-gamma in healthy blood donors. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;82:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb05403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shurkovich SV, Eremkina EI. Probable role of interferon in allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1975;35:356–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flores A, Olive A, Feliv E, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus following interferon therapy [Letter] Brit Rheumatol. 1994;33:787. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.8.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]