ABSTRACT

We detected a significant elevation of serum HSP90α levels in pancreatitis patients and even more in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients. However, there was no significant difference in the serum HSP90α levels between patients with early-stage and late-stage PDAC. To study whether elevation of serum HSP90α levels occurred early during PDAC development, we used LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre transgenic mice as a studying model. Elevated serum HSP90α levels were detected before PDAC formation and an extracellular HSP90α (eHSP90α) inhibitor effectively prevented PDAC development. Both serum HSP90α level and pancreatic lesion were suppressed when the mice were administered a CD11b-antagonizing antibody, suggesting that CD11b+-myeloid cells were associated with eHSP90α levels and pancreatic carcinogenesis. Consistently, in CD11b-DTR-EGFP transgenic mouse model with CD11b+-myeloid cells depletion, serum HSP90α levels were suppressed and Panc-02 cell grafts failed to develop tumors. Macrophages and granulocytes are two common tissue-infiltrating CD11b+-myeloid cells. Duplex in situ hybridization assays suggested that macrophages were predominant HSP90α-expressing CD11b+-myeloid cells during PDAC development. Immunohistochemical and immunohistofluorescent staining results revealed that HSP90α-expressing cells included not only macrophages but also pancreatic ductal epithelial (PDE) cells. Cell culture studies also indicated that eHSP90α could be produced by macrophages and macrophage-stimulated PDE cells. Macrophages not only secreted significant amount of HSP90α, but also secreted interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 to induce a JAK2−STAT3 signaling axis in PDE cells, stimulating them to express and secrete HSP90α. eHSP90α further promoted cellular epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration, and invasion in PDE cells. Besides myeloid cells, eHSP90α can be potentially taken as a target to suppress PDAC pathogenesis.

KEYWORDS: eHSP90α, K-Ras transgenic mice, macrophage, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, tissue microenvironment

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for >95% of pancreatic malignancies and is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in developed countries, with a 5-year survival rate <10% and a median survival as short as 6 months.1 The retroperitoneal location of the pancreas and the undetectable small size of most precursor lesions hamper the early diagnosis of PDAC. Even if the tumor can be surgically resected, recurrence or metastasis often occurs, eventually resulting in an extremely poor outcome. Discovery of early-stage diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets is an urgent and important issue for this intractable disease.

Many molecular alterations are associated with the PDAC development.2-4 For example, K-ras mutations, loss of p16 function, p53 inactivation, and Smad4 loss are found to occur in >90%, 90%, 50–75%, and 55% of PDAC patients, respectively. In transgenic mouse models, activating mutation in the K-ras gene is sufficient for the development of PDAC,5-7 through a stage-by-stage process described as acinar/centroacinar cells → acinar-to-ductal metaplasia (ADM) → pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) → PDAC.8 Investigation of clinical specimens has further suggested that rates of K-ras mutation in different stages are 0% (acinar cells), 63% (ADM), 74% (PanIN), and >90% (PDAC), respectively.9 Because the whole process is accompanied by chronic inflammation in pancreas,10,11 immune-related tissue microenvironment reprogramming can occur early to facilitate K-ras mutations and initiate PDAC carcinogenesis. The presence of abundant myeloid cells in pancreas is therefore thought as an important hallmark of PDAC development.

Macrophages, neutrophils, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are the most common CD11b+-myeloid cells infiltrating the tumor microenvironment.12 Macrophage infiltration has been clinically correlated with metastasis in many malignancies including PDAC.13-15 Earlier studies have demonstrated that tumor-infiltrating macrophages have tumoricidal activity. However, after interacting with tumor cells and other cells within the tumor microenvironment, macrophages release various cytokines and other factors that promote tumor cell migration, invasion, tumor angiogenesis, immune suppression, and tumor cell metastasis.16-18 Macrophages are also involved in early stages of carcinogenesis by secreting RANTES, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and heparin-binding epidermal growth factor to drive the process of ADM.19,20 Additionally, neutrophils are the most abundant granulocytes. Tumor-associated neutrophils may serve as the main producers of pro-angiogenic factors like matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 during pancreatic carcinogenesis.21 MDSCs play an important immunosuppressive role in tumor microenvironment, even though they exhibit high phenotypic and functional heterogeneities. Recently, granulocytic MDSCs (G-MDSCs), but not monocytic MDSCs, have found to be significantly increased in the tumor tissues of PDAC patients.22

HSP90 is initially identified as a cellular chaperone aiding the proper folding, maturation, and trafficking of numerous client proteins such as ErbB2/Neu, HIF-1α, mutated p53, Bcr-Abl, Akt, and Raf-1.23 Besides the localization at cytoplasm, nuclear HSP90 can regulate gene expression by interacting with RNA polymerase complex.24 HSP90α can also be secreted from keratinocytes and cancer cells.25-30 Accumulating evidence shows that extracellular HSP90α (eHSP90α) can stimulate cancer cell malignancy through binding to cell-surface protein CD91.26,29-31 In colorectal cancer (CRC) cells, eHSP90α−CD91 engagement elicits a NF-κB-dependent pathway to induce TCF12, integrin αV, and MMPs, promoting CRC cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), migration, and invasion.29,30 CD91 can also interact with EphA2 co-receptor for eHSP90 to facilitate lamellipodial formation and subsequent motility and invasion of glioblastoma cells.31 Recently, eHSP90α is also found to induce stemness in prostate cancer and CRC cells.32,33 Elevation of serum/plasma HSP90α levels has been detected in several malignancies including PDAC, non-small cell lung cancer, breast carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, CRC, and glioblastoma.27-31

In our present study, a significant elevation of serum HSP90α levels was detected from the patients diagnosed with pancreatitis or early-staged PDAC. Therefore, we wondered if elevation of HSP90α secretion occurred early during PDAC development, and if so, the biological functions involved were investigated. Because inflammation is closely associated with cancer development and malignant progression, we also studied the role(s) of myeloid cells in HSP90α secretion and PDAC development. To address these issues, transgenic mouse models and in vitro cell cultures were used.

Results

Elevation of serum HSP90α levels is associated with PDAC development

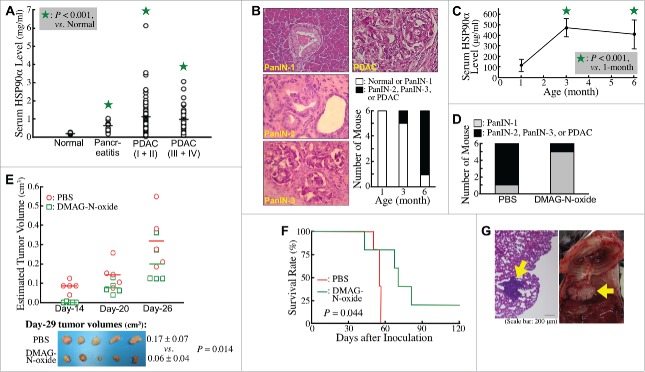

Clinically, higher HSP90α levels were detected in sera of pancreatitis patients compared with normal volunteers (0.57 ± 0.23 vs. 0.18 ± 0.05 mg/ml, P < 0.05, Fig. 1A). More elevated serum HSP90α levels were detected in PDAC patients (1.04 ± 0.86 mg/ml), although no significant difference was found between TNM stage-I/II patients and TNM stage-III/IV patients (1.08 ± 0.93 vs. 0.96 ± 0.69 mg/ml, P = 0.454), suggesting that elevation of serum HSP90α levels occurred early during PDAC development. To confirm this proposition, we investigated the change of serum HSP90α levels in LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre transgenic mice during their spontaneous PDAC development. Assessing the histopathological characteristics of pancreatic tissues, all (6/6) LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice were observed to develop ADM and PanIN-1 lesions as early as 3 months after birth, while most (5/6) were observed to develop PDAC lesions at 6 months of age (Fig. 1B). An obvious increase in HSP90α levels was detected in sera of 3-month-old mice, and this elevation was still evident at 6 months of age (Fig. 1C). We next investigated if the increased eHSP90α was involved in the PDAC development. DMAG-N-oxide,34 an eHSP90α inhibitor was administered to LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice since 1 month after birth. Pancreatic tissues were histologically examined at 7 months of age. Pancreatic carcinogenesis was efficiently repressed by DMAG-N-oxide treatment (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Elevation of secreted HSP90α levels during PDAC development. (A) Differences in average levels of serum HSP90α between normal volunteers (n = 10) and pancreatitis patients (n = 20), between normal volunteers and stage-I & II patients (n = 80), and between normal volunteers and stage-III & IV patients (n = 34) were all statistically significant (P < 0.05, designated by an asterisk). (B) Different stages of lesions identified in the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 1, 3, and 6 months of age (n = 6 in each age group) by Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining. Representative histopathological lesions of PanIN-1, PanIN-2, PanIN-3, and PDAC are shown and identified according to the characteristics described previously,41 200 ×. The tumor stage in each mouse was designated based on its most advanced lesions. (C) Serum HSP90α levels of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 1, 3, and 6 months of age (n = 6 in each age group; mean ± SD). (D) Inhibition of the PDAC development in LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice by DMAG-N-oxide treatment described in Materials and Methods. The mice were sacrificed at 7 months of age and examined for histopathological lesions in pancreatic tissues. (E) Inhibition of the tumor formation of Panc-02 cell grafts in C57 BL/6 mice by DMAG-N-oxide treatment described in Materials and Methods. The tumor sizes were measured superficially since Day-14 post-transplantation. The mice were sacrificed on Day-29 and the tumor volumes were calculated as ½ × length × width2 (cm3). (F) Inhibition of the metastasis of Panc-02 cell grafts in C57 BL/6 mice by DMAG-N-oxide treatment described in Materials and Methods. Survival rates of the mice were calculated and analyzed by Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. (G) Representative images of a tumor nodule in the H&E-stained lung tissue section (left panel) and a tumor mass behind the lung (right panel, photographed after pneumonectomy) obtained from PBS-treated Panc-02-inoculated mice.

To confirm the participation of eHSP90α in PDAC development, C57 BL/6 mice that had been subcutaneously transplanted with Panc-02 cell grafts were treated with DMAG-N-oxide. As expected, the tumor growth of Panc-02 cells was effectively attenuated by DMAG-N-oxide (Fig. 1E). On Day-29 post-transplantation, the average tumor size of DMAG-N-oxide-treated mice was significantly smaller than that of control mice with PBS treatment (0.06 ± 0.04 vs. 0.17 ± 0.07 cm3, P = 0.014). To further examine whether eHSP90α is involved in metastatic PDAC, C57 BL/6 mice were intravenously injected with Panc-02 cells and then treated with PBS or DMAG-N-oxide. As metastatic pancreatic cancer leads to a poor prognosis, survival rates of the mice were recorded (Fig. 1F). All 5 PBS-treated mice were died in 56 days after Panc-02 cell inoculation and tumor nodules were observed in their lungs (Fig. 1G, left panel). Two of them even had extra tumor masses adjacent to the lungs (Fig. 1G, right panel). In contrast, DMAG-N-oxide-treated mice exhibited no tumor nodules in lungs and survived longer than PBS-treated mice, except for one, which died on Day-43 with an obvious fight injury. Taken together, our data suggested that eHSP90α was not only associated with PDAC development but also with PDAC metastasis.

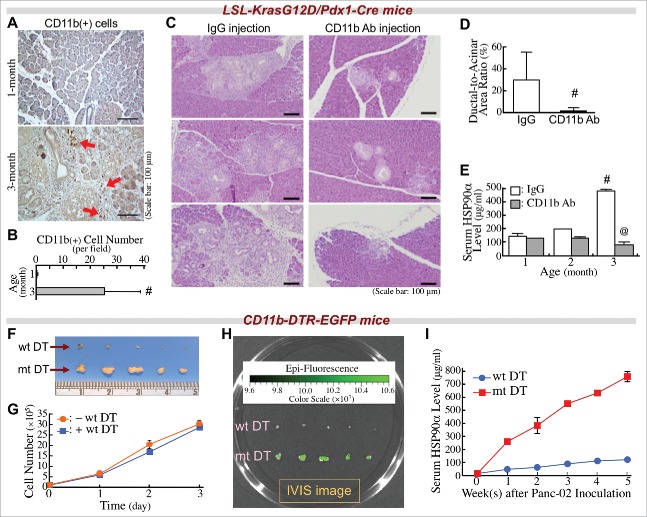

CD11b+-myeloid cells are associated with PDAC development and elevation of serum HSP90α

In our LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mouse approach, CD11b+-myeloid cells were obviously detected in the pancreatic tissues at 3 months of age, without PDAC lesions (Fig. 2A and B). We wondered if infiltrating CD11b+-myeloid cells were involved in PDAC development and induction of serum HSP90α levels. Antibody clone M1/70,35 an anti-CD11b monoclonal antibody was used to treat LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice. This antibody efficiently suppressed the pancreatic infiltration of CD11b+-myeloid cells (Fig. S1). When 1-month-old mice were administered this antibody, their pancreatic tissues exhibited significantly fewer ADM lesions compared to mice administered a control IgG at 3 months of age (Fig. 2C and D). We also measured serum HSP90α levels in these mice when they were 1, 2, and 3 months of age. A significant elevation from 3-month-old LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice administered control IgG was drastically suppressed when mice were administered anti-CD11b antibody (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Infiltrating CD11b+-myeloid cells are involved in PDAC carcinogenesis and elevation of serum HSP90α levels in LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice. (A) Immunohistochemical images showing CD11b+-myeloid cells (red arrows) infiltrating into the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3 months of age. (B) Quantification of CD11b+ cells from the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 1 and 3 months of age. #, P < 0.05 when compared with the data of 1-month-old mice. (C) Retardation of the ADM development in LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice upon treatment with anti-CD11b antibody as described in Materials and Methods. The mice were sacrificed at 3 months of age, and their pancreatic tissue sections were stained with H&E to identify ADM status. (D) Quantification of ADM levels by calculating the ratios of ductal regions to acinar regions in the pancreatic tissue sections of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice treated as described in (C). (E) Reduction of serum HSP90α levels in LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice upon treatment with anti-CD11b antibody as described in (C). #, P < 0.05 when compared with the average serum HSP90α level of mice at 1 month of age. @, P < 0.05 when compared with the average serum HSP90α level of mice administered control IgG. (F) Inhibition of the tumor formation of Panc-02 cell grafts in CD11b-DTR-EGFP mice upon treatment with wild-type (wt) but not with mutant (mt) DT as described in Methods. (G) No significant inhibition of Panc-02 cell proliferation by wt DT treatment. After incubation with 2.5 nM of wt DT for 1, 2, or 3 days, the cells excluding trypan blue were counted for plotting the cell proliferation curves. (H) Infiltrating CD11b+-myeloid cells were detected in the tumor masses of mt DT-treated mice by using an IVIS imaging system. (I) HSP90α levels in sera of mice treated as described in (F). Sera were collected every week after the Panc-02 cell inoculation.

To further confirm the involvement of CD11b+-myeloid cells in elevation of serum HSP90α levels and tumor development, another transgenic mouse model with a CD11b-DTR-EGFP genotype was used. These mice were treated with diphtheria toxin (DT) for depletion of CD11b+-myeloid cells. As expected, Panc-02 cancer cell grafts did not significantly develop tumor masses (Fig. 2F). The repression of tumor formation was not due to the direct inhibition of Panc-02 cell proliferation by DT, because there was no significant difference between the growth curves of Panc-02 cells with or without DT treatment (Fig. 2G). In mice treated with mutant DT as a control, Panc-02 tumor masses were observed with green fluorescence, indicating the presence of tumor-infiltrating CD11b+-myeloid cells (Fig. 2H). In accordance with these results, elevation of serum HSP90α levels was abolished in CD11b-DTR-EGFP mice administered wild-type DT but not mutant DT (Fig. 2I). Taken together these observations, pancreas-infiltrating CD11b+-myeloid cells were associated with elevation of serum HSP90α levels and PDAC development.

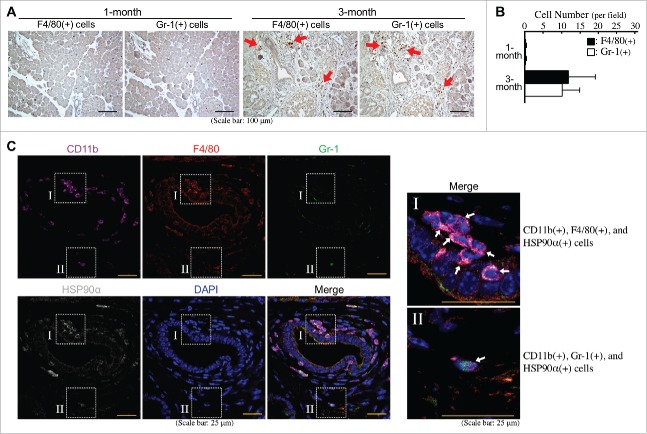

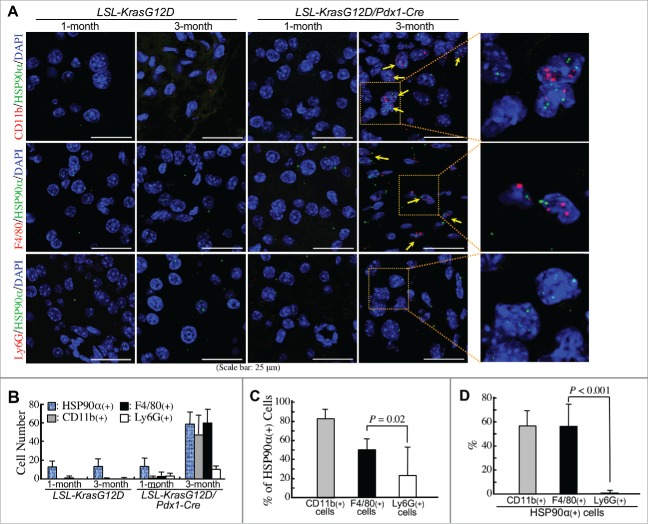

Macrophages account for most HSP90α-expressing myeloid cells during PDAC development

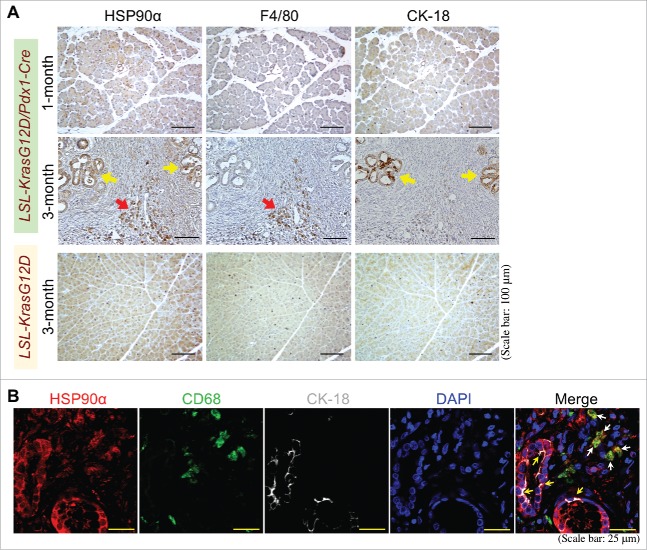

Macrophages and granulocytes are two common CD11b+-myeloid cells infiltrating PDAC tissues. Indeed, F4/80+ cells (macrophages) and Gr-1+ cells (granulocytes) were obviously detected at comparable levels in the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3 months of age (Fig. 3A and B). Immunohistofluorescent staining was performed to investigate whether these cells could express HSP90α. As shown in Fig. 3C, most CD11b+ and F4/80+ cells (myeloid-derived macrophages) and a few CD11b+ and Gr-1+ cells (myeloid-derived granulocytes probably including G-MDSCs) were detected to express HSP90α. Given the Gr-1 antibody (RB6-8C5) mainly detected Ly6G with a weak cross-reactivity with Ly6C, we furthermore performed duplex in situ hybridization assays to confirm the status of HSP90α mRNA expression in F4/80 mRNA-expressing macrophages and Ly6G mRNA-expressing granulocytes. HSP90α-expressing CD11b+-myeloid cells, F4/80+-macrophages, and Ly6G+-granulocytes were detected only in the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3 months of age but not in the pancreatic tissues of 1-month-old LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice and 1- and 3-month-old LSL-KrasG12D mice (Fig. 4A). The quantitative result indicated that the numbers of HSP90α+ cells, CD11b+ cells, F4/80+ cells, and Ly6G+ cells were all increased significantly in the pancreatic tissues of 3-month-old LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice (Fig. 4B). A further analysis of the data indicated that HSP90α expression was detected in ∼80% of CD11b+ cells, ∼50% of F4/80+ cells, and ∼22% of Ly6G+ cells, respectively (Fig. 4C). We also quantified the percentages of CD11b+ cells, F4/80+ cells, and Ly6G+ cells, respectively, from HSP90α-expressing cells. The data show that CD11b+-myeloid cells and F4/80+-macrophages were both responsible for ∼57% of HSP90α+ cells in the pancreatic tissues of 3-month-old LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice (Fig. 4D), suggesting that macrophages were predominant HSP90α-expressing CD11b+-myeloid cells during PDAC development.

Figure 3.

Abundant HSP90α-expressing myeloid-derived macrophages in the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice prior to PDAC formation. (A) Immunohistochemical staining images showing F4/80+ cells (macrophages) and Gr-1+ cells (granulocytes) infiltrating into the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3 months of age. (B) Quantification of F4/80+ cells and Gr-1+ cells from the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 1 and 3 months of age. (C) Immunohistofluorescent staining images showing HSP90α expression in CD11b+ and F4/80+ cells (myeloid-derived macrophages) rather than CD11b+ and Gr-1+ cells (myeloid-derived granulocytes probably including G-MDSCs) in the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3 months of age.

Figure 4.

Confirmation of macrophages as predominant HSP90α-expressing CD11b+-myeloid cells during PDAC development. (A) Duplex in situ hybridization assays showing that F4/80+ cells rather than Ly6G+ cells were the HSP90α-expressing CD11b+ myeloid cells in the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3 months of age. The HSP90α+ cells with simultaneous CD11b+, F4/80+, or Ly6G+ were not detected from the pancreatic tissues of 1-month-old LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice and 1- or 3-month-old LSL-KrasG12D mice. (B) Quantification of the cells with HSP90α+, CD11b+, F4/80+, and Ly6G+, respectively, from the pancreatic tissue sections described in (A). (C) Quantification of the % of HSP90α+ cells from CD11b+, F4/80+, and Ly6G+ cells, respectively, from the pancreatic tissue sections of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3 months of age. (D) Quantification of the % of CD11b+, F4/80+, and Ly6G+ cells, respectively, from HSP90α+ cells from the pancreatic tissue sections of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3 months of age.

Macrophages induced JAK2–STAT3-mediated HSP90α expression/secretion in HPDE cells

Clinically, we detected large amounts of macrophages from the cancer tissues of PDAC patients (Fig. S2A). The infiltration level of CD68+ cells (pan-macrophages) was not significantly correlated with clinical parameters including patients' age, tumor size, tumor staging, and metastatic status, but higher infiltration levels of CD163+ cells (M2-type macrophages) were preferentially detected in the patients diagnosed with metastasis compared to the patients without metastasis (P = 0.013, Fig. S2B). However, both levels of CD68+ and CD163+ cells were not correlated with serum HSP90α levels, suggesting that macrophage-expressed HSP90α alone could not sufficiently account for serum HSP90α levels.

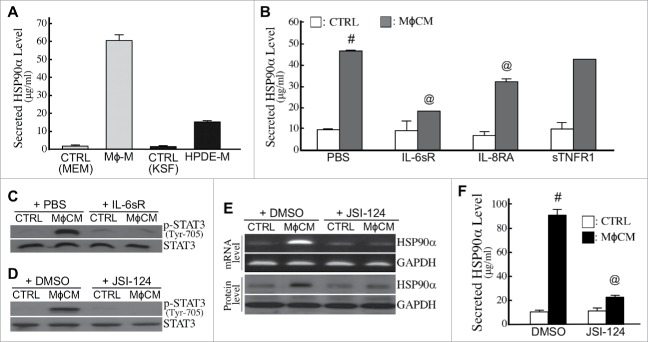

Apart from HSP90α in serum, we analyzed HSP90α expression in the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D and LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice. Abundant HSP90α-expressing cells were detected in the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3 months of age but not from the pancreatic tissues of 1-month-old LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice and 3-month-old LSL-KrasG12D mice (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, these HSP90α-expressing cells included not only macrophages but also pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (Fig. 5A). This phenomenon was also observed from patients' PDAC tissues (Fig. 5B), suggesting that elevation of serum HSP90α levels could result from the expression and secretion of HSP90α from macrophages and macrophage-stimulated pancreatic ductal epithelial cells. To support this proposition, two human cell lines, pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (HPDE) and macrophages (differentiated THP-1), were cultivated and their culturing media were collected after 24 h. The average HSP90α levels in macrophage-culturing media and HPDE-culturing media were 60.54 ± 3.29 μg/ml and 15.30 ± 0.36 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, when HPDE cells were pre-treated for 24 h with control medium or macrophage-conditioned medium (MϕCM) and then incubated with fresh culture medium for another 24 h, the average HSP90α levels were significantly increased from 9.69 ± 0.20 μg/ml to 44.59 ± 2.68 μg/ml (P = 0.003, Fig. 6B), suggesting that MϕCM stimulated HPDE cells to secrete HSP90α.

Figure 5.

Pancreatic macrophages and ductal epithelial cells are two HSP90α-expressing cells during PDAC development. (A) Sequential pancreatic tissue sections from 1- or 3-month-old LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice or 3-month-old LSL-KrasG12D mice were immunohistochemically stained with the antibodies against HSP90α, F4/80, and CK-18, respectively. The example images revealed that HSP90α+ cells were detected abundantly from the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3 months of age but not from the pancreatic tissues of 1-month-old LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice and 3-month-old LSL-KrasG12D mice. These HSP90α-expressing cells included not only F4/80+ cells (macrophages, red arrow) but also CK-18+ cells (ductal epithelial cells, yellow arrows). (B) Example images of immunohistofluorescent staining of patients' PDAC specimens with HSP90α, CD68, and CK-18 antibodies, showing that HSP90α was expressed not only in macrophages (CD68+ cells, white arrows) but also in ductal epithelial cells (yellow arrows).

Figure 6.

Expression and secretion of HSP90α from macrophages and macrophage-stimulated pancreatic ductal cells. (A) Secreted HSP90α levels in macrophage- and HPDE-culturing media (designated as Mϕ-M and HPDE-M, respectively) collected as described in Materials and Methods. The mean ± SD values of three independent experiments are shown. (B) HSP90α levels secreted from macrophage-conditioned HPDE cells. HPDE cells were treated 24 h with control medium (CTRL) or MϕCM in the absence or presence of 10 ng/ml IL-6sR, 0.5 μg/ml IL-8RA, or 50 ng/ml sTNFR1, and incubated with fresh KSF medium for another 24 h. Media were collected and assayed for secreted HSP90α levels as described in Methods. #, P < 0.05 when compared with the average HSP90α level secreted by CTRL-treated HPDE cells. @, P < 0.05 when compared with the average HSP90α level secreted from HPDE cells treated with MϕCM plus PBS or preimmune IgG. (C) Tyr-705-phosphorylated STAT3 and total STAT3 levels in HPDE cells treated 6 h with control medium (CTRL) or MϕCM in the absence or presence of 10 ng/ml IL-6sR. (D) Tyr-705-phosphorylated STAT3 and total STAT3 levels in HPDE cells treated 6 h with control medium (CTRL) or MϕCM in the absence or presence of 10 μM JSI-124. (E) mRNA and protein levels of HSP90α in HPDE cells treated 24 h with control medium (CTRL) or MϕCM in the absence or presence of 10 μM JSI-124. (F) HSP90α levels secreted from HPDE cells treated 24 h with control medium (CTRL) or MϕCM in the absence or presence of 10 μM JSI-124. #, P < 0.05 when compared with the data of CTRL treatment. @, P < 0.05 when compared with the data of control DMSO.

We previously identified the components of MϕCM which included inflammatory factors such as interleukin (IL)-8 (1851.5 pg/ml), TNF-α (29.5 pg/ml), and IL-6 (2.3 pg/ml). To determine if IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-6 were involved in MϕCM-stimulated HSP90α secretion, HPDE cells were treated with MϕCM in the presence of IL-8 receptor-antagonizing antibody (IL-8RA), soluble TNF-α receptor 1 (sTNFR1), or soluble IL-6 receptor (IL-6sR). The effect of MϕCM was significantly antagonized by IL-6sR and IL-8RA, especially by IL-6sR (Fig. 6B). The JAK2−STAT3 pathway is reported to be elicited by IL-6. Indeed, MϕCM treatment induced cellular STAT3 phosphorylation, which could be repressed by IL-6sR (Fig. 6C) and JSI-124, a selective inhibitor of the JAK2−STAT3 pathway (Fig. 6D). mRNA and protein levels of HSP90α induced by MϕCM were also suppressed by JSI-124 in HPDE cells (Fig. 6E). Consistently, the increase of secreted HSP90α levels in culture media was abolished when HPDE cells were treated with MϕCM in the presence of JSI-124 (Fig. 6F). Together, these results suggest that macrophages did not only secrete HSP90α but also secreted IL-6 and IL-8 to induce the JAK2−STAT3 pathway in HPDE cells to express and secrete HSP90α.

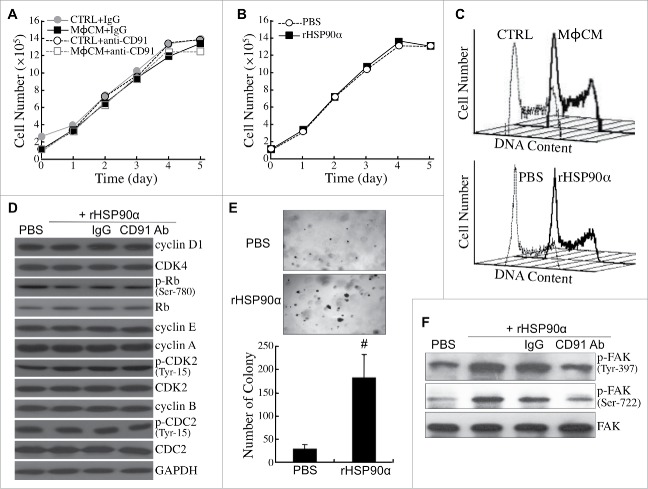

eHSP90α induces malignant transformation of HPDE cells

Next, we investigated whether eHSP90α could induce malignant transformation of HPDE cells. MϕCM did not change the proliferative rate of HPDE cells in the absence or presence of the antibody antagozinig CD91 (Fig. 7A). Purified recombinant HSP90α (rHSP90α) did not affect HPDE cell proliferation either (Fig. 7B). Consistently, both MϕCM and rHSP90α did not exhibit any significant effect on the cell-cycle phase distribution of HPDE cells (Fig. 7C). The levels or activities of several key cell-cycle regulatory proteins were not significantly changed in rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells (Fig. 7D). However, rHSP90α significantly stimulated anchorage-independent proliferation of HPDE cells (Fig. 7E). Activation of FAK, a protein kinase related to cellular anchorage independence, with phosphorylations at Tyr-397 and Ser-722, was efficiently induced by rHSP90α, but was drastically inhibited by the antibody antagozinig CD91 (Fig. 7F).

Figure 7.

eHSP90α had a stimulatory effect on HPDE cell anchorage independence but not cell proliferation. (A) Growth curves of HPDE cells treated with control medium (CTRL) or MϕCM for 1 to 5 days in the presence of control IgG or anti-CD91 antibody. Trypan blue exclusion assay was performed to count the numbers of viable cells. The data represent the averages of three independent experiments, and each experiment was performed in triplicate. (B) Growth curves of HPDE cells treated with PBS or 15 μg/ml of rHSP90α for 1 to 5 days. Trypan blue exclusion assay was performed, and the averages of three independent experiments are shown. (C) Flow cytometric analyses of the cell-cycle phase distribution of control medium (CTRL)- vs. MϕCM-treated HPDE cells (upper panel) and PBS- vs. rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells (lower panel). HPDE cells were treated for 24 h and trypsinized for ethanol fixation and propidium iodide staining. The histograph of cell-cycle phases was obtained from 10000 cells analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer. (D) The levels of cyclin D1, CDK4, Ser-780-phosphorylated Rb, Rb, cyclin E, cyclin A, Tyr-15-phosphorylated CDK2, CDK2, cyclin B, Tyr-15-phosphorylated CDC2, CDC2, and GAPDH in HPDE cells treated with PBS, 15 μg/ml rHSP90α, or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α plus preimmune IgG or anti-CD91 antibody. (E) Soft-agar colony-forming assay of PBS or rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells. HPDE cells (2000 cells seeded on the soft-agar layer in each well of a 6-well plate) were treated with or without 15 μg/ml rHSP90α and refreshed every 3 days for 3 weeks. The colonies were stained with Giemsa and photographed under a microscope (100 ×); only colonies consisting of ≥80 cells were counted. The mean ± SD values of three independent experiments are shown, and each experiment was performed in triplicate. #, P < 0.05 when compared with the data of PBS-treated cells. (F) Phosphorylated FAK and total FAK levels in HPDE cells treated with PBS, rHSP90α, or rHSP90α plus control IgG or anti-CD91 antibody.

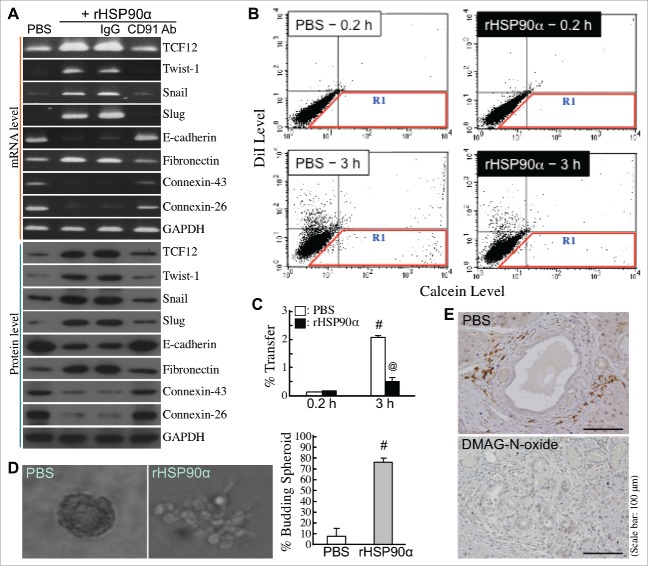

We next studied whether rHSP90α could induce EMT in HPDE cells. Cellular mRNA and protein levels of E-cadherin, connexin-26, and connexin-43 were downregulated under rHSP90α treatment, whereas mRNA and protein levels of fibronectin and EMT-inducing transcription factors such as TCF12, Twist-1, Snail, and Slug were induced in rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells (Fig. 8A). Additionally, rHSP90α treatment repressed cellular gap-junction activity (Fig. 8B and C) and promoted cellular outgrowth from 3-D spherical structures (Fig. 8D). In vivo TCF12-expressing pancreatic cells which located at the invasive front edges of hyperplastic lesions originating from proliferating ductal epithelial cells were observed in control but not in DMAG-N-oxide-treated LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice (Fig. 8E). These data together suggest that eHSP90α induced EMT in HPDE cells.

Figure 8.

Induction of EMT by eHSP90α in pancreatic ductal epithelial cells. (A) mRNA and protein levels of TCF12, Twist-1, Snail, Slug, E-cadherin, fibronectin, connexin-26, connexin-43, and GAPDH in HPDE cells treated with PBS, 15 μg/ml rHSP90α, or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α plus control IgG or anti-CD91 antibody. (B,C) The Calcein-transfer assay was performed to evaluate gap-junction activity of HPDE cells treated 24 h with PBS or 15 μg/ml of rHSP90α. Treated HPDE cells were labeled with Calcein acetoxymethyl ester and DiI dyes and then added to a monolayer of unstained, untreated HPDE cells for 0.2 or 3-h co-culture. Finally, the monolayer of cells were trypsinized and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative dot plots are shown in (B). The cells in the R1 region were categorized as Calcein-accepting cells. The ratio of Calcein-accepting cells (designated as “% Transfer”) was quantified by the CellQuest software, and mean ± SD values of three independent experiments have been provided to indicate that cellular gap-junction activity was significantly inhibited after rHSP90α treatment (C). #, P < 0.05 when compared with the data of PBS-treated cells at 0.2 h. @, P < 0.05 when compared with the data of PBS-treated cells at 3 h. (D) rHSP90α induced the invasive outgrowth of HPDE cells from 3-D spherical structures. HPDE cells were cultivated in 2% Matrigel-supplemented medium until the formation of spherical structures was observed. These cell spheroids were furthermore treated with 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for 72 h. Morphological changes were observed under an Olympus IX 71 inverted microscope. The left panel shows a typical cell spheroid and a budding, branching cell spheroid. The quantified data are shown in the right panel. #, P < 0.05 when compared with the data of PBS-treated cell spheroids. (E) Immunohistochemical analysis showing that TCF12-expressing pancreatic cells, located at the invasive front edges of hyperplastic lesions, were present in control but not in DMAG-N-oxide-treated LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice.

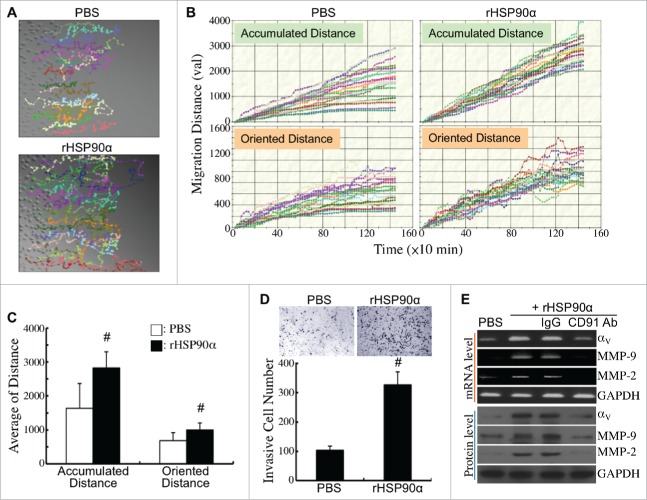

The effects of rHSP90α on HPDE cell migration and invasion were also investigated. The migration tracks of PBS- or rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells were monitored by time-lapse photography (Fig. 9A). Quantification result showed that both accumulated and oriented migration distances were significantly increased in rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells compared with control cells (Fig. 9B and C). Moreover, rHSP90α induced HPDE cell invasion as shown in conventional Matrigel invasion assay (Fig. 9D). mRNA and protein levels of integrin αV, MMP-9, and MMP-2 were significantly induced in rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells; as expected, anti-CD91 antibody blocked this induction (Fig. 9E).

Figure 9.

Induction of HPDE cell migration and invasion by eHSP90α. (A) Cell migration tracks of HPDE cells treated with PBS or 15 μg/ml of rHSP90α. Cell migration was monitored for 24 h using time-lapse photography, and the movement tracks of twenty randomly selected PBS or rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells were analyzed by Image-Pro Plus software. (B) Quantification of the accumulated and oriented migration distances of the PBS or rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells selected in panel A. (C) Comparison of the average accumulated migration distances and oriented migration distances between the PBS and rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells. The data are expressed as mean ± SD values of three independent experiments. #, P < 0.05 when compared with the data of PBS-treated cells. (D) Transwell invasion assays of PBS or rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells. HPDE cells, incubated with or without 15 μg/ml of rHSP90α, were seeded in the top chambers of the Transwell inserts, and allowed to invade through the Matrigel for 16 h. Invasive cells on the filters of the Transwell inserts were counted by Image-Pro Plus software. The mean ± SD values of three independent experiments are shown. #, P < 0.05 when compared with the data of PBS-treated cells. (E) mRNA and protein levels of integrin αV, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in HPDE cells treated with PBS, 15 μg/ml rHSP90α, or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α plus control IgG or anti-CD91 antibody.

Discussion

The chaperone protein HSP90α can be secreted by cancer cells under the microenvironment stresses like nutrient deficiency and hypoxia.28,29 Given that eHSP90α is an inducer of cellular EMT, migration, and invasion, the secretion of HSP90α can be thought as a strategy adopted by cancer cells to promote metastasis. Investigation of serum/plasma HSP90α levels and their relevance to clinical outcome is essential for evaluating the possibility of taking eHSP90α level as a marker of malignant progression. In our clinical study, a significant elevation of HSP90α levels was detected in sera of pancreatitis patients and even more in PDAC patients. However, there was no significant difference between low-staged and higher-staged PDAC patients, which was consistent with the result we had obtained from a cohort of 172 CRC patients.29 We were therefore intrigued to study whether elevation of serum HSP90α levels occurred early during PDAC development. To confirm this, LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre transgenic mice were measured serum HSP90α levels during their PDAC development process. LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice developed pancreatic ADM within 3 months after birth, PanIN from 3 to 6 months after birth, and PDAC lesions after 6 months of age. A significant increase in serum HSP90α levels was found in these mice at 3 months of age, and it could still be detected after 6 months. Retardation of pancreatic carcinogenesis by DMAG-N-oxide further suggested an early involvement of secreted HSP90α in PDAC development. Besides secreted HSP90α, we also observed a significant elevation of cellular HSP90α expression in tumor tissues when compared with adjacent non-tumor tissues in almost all PDAC and CRC patients we have studied. The elevated HSP90α was also not correlated with patients' disease staging and survival. Analysis of another cohort of PDAC patients from the Oncomine database (Collisson Pancreas, GSE17891) also revealed no significant correlation between HSP90α mRNA expression level and overall survival of patients (95% confidence interval of hazard ratio = 0.60∼1.40, P = 0.685). Taken together, an early and promoting role played by expression and secretion of HSP90α was suggested during PDAC development.

Change of tissue microenvironment has been known as a prerequisite for cancer development and metastasis.36 Aside from HSP90α in sera, myeloid cell infiltration was abundantly detected in the pancreas of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice before PDAC lesions. Because pancreatic carcinogenesis is accompanied by chronic inflammation, inflammatory cells and their secretory factors can be involved in tissue microenvironment reprogramming to facilitate neoplasm formation and progression. Indeed, myeloid cells are known to secrete IL-6 to induce STAT3 activation in pancreatic cells in order to promote PanIN progression.37 It has also been reported that macrophages secrete RANTES, TNF-α, and heparin-binding epidermal growth factor to drive ADM process.21,22 In our present study, two sets of transgenic mouse experiments were performed to demonstrate the involvements of CD11b+-myeloid cells and secreted HSP90α in PDAC development. First, LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice were administered an anti-CD11b antibody to block the pancreatic infiltration of CD11b+-myeloid cells. The development of PDAC lesions and the elevation of serum HSP90α level were thus repressed. Second, Panc-02 cancer cell grafts could not develop tumor masses in the CD11b-DTR-EGFP mice treated with DT to deplete CD11b+-myeloid cells. In this set of experiment, CD11b+-myeloid cells were also required for the elevation of HSP90α levels in sera. Macrophages and granulocytes are two common tissue-infiltrating CD11b+-myeloid cells. Both of them were abundantly detected in the pancreatic tissues of LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice at 3-month age. The results of the duplex in situ hybridization suggested that macrophages rather than granulocytes accounted for most of the HSP90α-expressing CD11b+-myeloid cells during the PDAC development. Furthermore, we observed not only macrophages secreted HSP90α, but ductal epithelial cells secreted it as well in the pancreatic tissues of 3-month-old LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice. Macrophages not only secreted significant amount of HSP90α, but also secreted IL-6 and IL-8 to induce the JAK2−STAT3 signaling pathway in HPDE cells, stimulating them to express and secrete HSP90α. It is possible that other inflammatory cells can also activate pro-inflammatory cascades leading to HSP90α expression. Multiple cell sources of HSP90α could explain why pancreatic macrophage levels were not correlated with serum HSP90α levels in PDAC patients.

To study how eHSP90α promoted PDAC development, we investigated the effects of purified rHSP90α on HPDE cells. rHSP90α has been shown to increase cellular EMT, migration, and invasion in cancer cells via cell-surface receptor CD91.26,29-31 Consistent with these reported results, rHSP90α induced expression of transcriptional factors TCF12, Twist-1, Snail, and Slug, and also stimulated cellular EMT, migration, and invasion in HPDE cells, suggesting that rHSP90α was a potent inducer of malignancy in HPDE cells. It seems that in the pancreas with macrophage infiltration, secreted HSP90α acts in a paracrine or autocrine manner to induce tumorigeneity in ductal cells. It remains to be investigated if eHSP90α treatment can enhance the mutation rate of K-Ras gene in HPDE cells. Considering >90% of PDAC patients exhibit activated K-Ras mutants2-4 and most K-Ras mutations may occur during ADM,9 an inflammatory and stressful tissue microenvironment could be a niche for pancreatic ductal cells to acquire K-Ras mutations and further develop into PDAC-initiating cells.

In our study, the eHSP90α inhibitor DMAG-N-oxide efficiently prevented the PDAC development in LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice. For further therapeutic implications, DMAG-N-oxide efficiently retarded the tumor formation of subcutaneously injected cell grafts and the mortality caused by intravenously injected cancer cells, as well as the elevation of serum HSP90α levels. However, secreted HSP90α levels were recovered in these mice due to exhaustion of the DMAG-N-oxide. The maximal tolerance dose of DMAG-N-oxide in C57 BL/6 mice was estimated to be 50∼100 μg/g. The amount of 5 μg/g for each dose and 4 doses per mouse were considered as non-toxic to mice, but swollen spleens were observed in DMAG-N-oxide-treated Panc-02-transplanted mice. More studies are required to investigate further effects of eHSP90α and DMAG-N-oxide on immune cells. Recently, anti-HSP90α antibody has been reported to exhibit anti-cancer efficacies in CRC mouse models.38 In view of this, several anti-HSP90α monoclonal antibodies have been developed and their efficacies against PDAC development and progression will be further evaluated.

In conclusion, pancreatic infiltration of myeloid cells is an early event leading to reprogramming of pancreatic tissue microenvironment for PDAC development. One underlying mechanism could be through production of eHSP90α that acts in an autocrine or paracrine manner to induce pancreatic ductal epithelial cells to acquire the characteristics of malignancy. Besides myeloid cells, eHSP90α can be potentially taken as a target to suppress PDAC pathogenesis.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

Serum samples were collected from 10 healthy volunteers, 20 pancreatitis patients, and 114 PDAC patients at Taipei Veterans General Hospital (Taipei, Taiwan). Additionally, tissue sections from 99 PDAC patients were analyzed in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from each sample donor in accordance with the medical ethics protocol approved by the Human Clinical Trial Committee of Taipei Veterans General Hospital.

Cell culture

Panc-02 mouse pancreatic cancer cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine, and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.39 Human HPDE cells were grown in keratinocyte serum-free (KSF) medium supplemented with bovine pituitary extract and epidermal growth factor (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA).40 To collect HPDE-culturing medium (designated as HPDE-M), 2 × 106 HPDE cells were seeded in a 10-cm plate and incubated with 10 ml of fresh medium. After incubation for 24 h, the medium was collected and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter for the subsequent measurement of secreted HSP90α. The medium collected from a plate that was set up in parallel but without HPDE cells was used as a control and designated as CTRL(KSF). Human monocytic leukemia THP-1 cells were cultivated in minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine. THP-1 cells (2 × 106 cells per 10-cm plate) were induced by 100 ng/ml of 12-O-tetradecanoyl-13-phorbol acetate for 16 h to differentiate into macrophages. To collect macrophage-culturing medium (designated as Mϕ-M), 1 × 106 macrophages were seeded in a 10-cm plate containing 10 ml of fresh MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine. After incubation for 24 h, the medium was collected and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter for the subsequent assay of secreted HSP90α. The medium collected from a plate without macrophages was used as a control and designated as CTRL(MEM). For preparation of macrophage-conditioned medium (MϕCM), 1 × 106 macrophages were seeded in a 10-cm plate containing 10 ml of serum-free MEM. A plate containing serum-free MEM without macrophages was used in parallel as a control. After incubation for 24 h, media were collected, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, and subsequently used as MϕCM and control medium, respectively, to treat HPDE cells.

Transgenic mouse models

Breeders of LSL-KrasG12D and Pdx1-Cre transgenic mice were provided by the Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium Repository of the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, Maryland, USA). LSL-KrasG12D mice were crossed with Pdx1-Cre mice to generate LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice. To investigate the role of eHSP90α in PDAC development, LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice were intravenously injected with three doses of PBS or 5 μg/g DMAG-N-oxide. The first dose was at 1 month of age, the second dose was 1 week after the first, and the final dose was given 2 weeks after the second. The mice were sacrificed at 7 months of age and the histopathological lesions in pancreatic tissues were examined. To explore whether CD11b+-myeloid cells were involved in PDAC carcinogenesis, LSL-KrasG12D/Pdx1-Cre mice were intraperitoneally injected with 100 μg per injection of preimmune IgG or anti-CD11b antibody (clone M1/70; BioXcell, West Lebanon, NH, USA) at Days 28, 33, 38, 45, 52, 59, 66, 73, 80, and 87 after birth (n = 5 for each group). These mice were sacrificed at 3 months of age, and pancreatic tissue sections were stained with H&E to identify ADM status. Additionally, breeders of CD11b-DTR-EGFP transgenic mouse were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). CD11b-DTR-EGFP mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 3 × 105 Panc-02 cells; 3 days later, the mice were intraperitoneally injected thrice with 10 ng/g of wild-type or mutant DT at 3-daily intervals (n = 5 for each group). On Day-35 post-inoculation, tissue masses at the inoculation sites were surgically resected for analysis using IVIS Imaging System 200 Series (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Mouse tumor transplant models

The eHSP90α inhibitor, DMAG-N-oxide was produced and purified to a >95% purity by RDD Lab, Inc. (New Taipei City, Taiwan). The anti-cancer efficacies of DMAG-N-oxide were evaluated in the mice transplanted with PDAC cell grafts through subcutaneous and tail-vein injections, respectively. First, Panc-02 cells were mixed with Matrigel and subcutaneously injected into C57 BL/6 mice (1 × 106 cells per mouse). The inoculated mice were then treated with 4 doses of 5 μg/g DMAG-N-oxide or PBS solvent (n = 5 per group). The first two doses were at 24 h and 48 h post-inoculation, the third dose was 48 h after the second, and the final dose was 72 h after the third. The sizes of developing tumors were superficially measured using a caliper since Day-14 post-inoculation, and the real tumor volumes were measured after the tumors surgically removed from the mice on Day-29. The tumor volumes were calculated as ½ × length × width2 (cm3). Additionally, we investigated the effect of DMAG-N-oxide on the metastatic occurrence and mortality of the C57 BL/6 mice inoculated with Panc-02 cells (3 × 105 cells per mouse) through tail-vein injection. The mice started to be treated with PBS or 5 μg/g DMAG-N-oxide (n = 5 per group) at 24 h post-inoculation. The second dose was given 24 h after the first, and the final dose was 48 h after the second. The survival rates of the treated mice were calculated by Kaplan-Meier method and analyzed by log-rank test.

Immunohistochemical staining

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through a series of ethanol dilutions, and boiled for 10 min in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Endogenous peroxidase activity was suppressed by exposure to 1% H2O2 for 15 min. The tissue sections were then blocked with 5% BSA and incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against CD11b (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), F4/80 (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC, USA), Gr-1 (GeneTex Inc., Hsinchu City, Taiwan), mouse HSP90α (GeneTex Inc.), mouse CK-18 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and mouse TCF12 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibody detection was performed using the DAKO REAL EnVision Detection System (Produktionsvej 42, DK-2600 Glostrup, Denmark).

Immunohistofluorescent staining

Tissue sections with a 4-µm thickness were deparaffinized by xylene and then rehydrated by a series of ethanol dilutions. Antigen retrieval was carried out by heating 15 min in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0. The tissue sections were then blocked in 3% BSA in PBS for 30 min. For mouse tissue staining, the tissue sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with goat anti-CD11b antibody (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-6614), rat anti-F4/80 antibody (1:100, AbD Serotec, MCA497R), and mouse anti-HSP90α antibody (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-515081). After PBS washes, anti-goat IgG-Alexa Fluor 647 and anti-rat IgG-Alexa Fluor 594 antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were applied. After incubation for another hour, Alexa Fluor 488 anti-Gr-1 antibody (1:80, Biolegend, #108417, San Diego, CA, USA) and anti-mouse IgG-DyLight 549 antibody (Rockland, Limerick, PA, USA) were applied and nuclei were stained with 4',6'-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). For human tissue staining, the tissue sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-CD68 antibody (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-20060) and rabbit anti-HSP90α antibody (1:100, GeneTex Inc., GTX109753). After washes, anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 and anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 568 antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Alexa Fluor 647 anti-CK-18 antibody (1:100, Biolegend, #628404) were applied and nuclei were stained with DAPI. Results were observed and photographed under Leica TCS SP5 II confocal microscope and LASAF software (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Duplex in situ hybridization

Mice were transcardially perfused with cold 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Paraffin-embedded pancreatic tissue sections with a 4-µm thickness were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a series of ethanol dilutions. RNA in situ hybridization was performed using the ViewRNA ISH Tissue 2-Plex Assay Kit (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Oligonucleotide probes were designed against HSP90α (NM_010480), Ly6G (NM_001310438), and F4/80 (NM_010130). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. The results were observed and photographed under a Leica TCS SP5 II confocal microscope and LASAF software. The thickness of the slide sectionedly scanned by lasering of confocal microscopy was 0.6∼1.0 µm.

Immunoblot analysis

Cell lysate was prepared using lysis buffer consisting of 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 0.3% SDS, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride.29 Immunoblot analyses were performed according to the procedure described previously.29 The antibodies used were specific for human STAT3, phosphorylated STAT3 (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), HSP90α (AbD Serotec), phosphorylated FAK (Invitrogen), phosphorylated CDK2 (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA), phosphorylated Rb, Rb, phosphorylated CDC2 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), connexin-43 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), integrin αV (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), cyclin D1, MMP-2, MMP-9 (Lab Vision/NeoMarkers Co., Fremont, CA, USA), CDK4, cyclin E, cyclin A, CDK2, cyclin B1, CDC2, FAK, TCF12, Twist-1, Snail, Slug, E-cadherin, connexin-26, fibronectin, and GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

RT-PCR

Total RNA of treated HPDE cells was extracted using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). One microgram of RNA was subjected to reverse transcription using Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus reverse transcriptase (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland). The resultant cDNA was used as the templates for PCR analyses. The primers and reaction conditions were listed in Table S1. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed in a RotorGene 3000 system (Corbett Research, Mortlake, Australia) using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Cambrex Co., East Rutherford, NJ, USA), and the data were analyzed using RotorGene software v5.0.

Growth curve and cell-cycle phase analyses

HPDE cells were seeded in 6-well plates (1 × 105 cells per well) and treated with PBS or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for 1∼5 days. After treatment, cells were trypsinized and suspended in PBS. Viable cells were immediately counted using a hemocytometer based on trypan blue dye exclusion. To analyze the cell-cycle phase distribution, PBS or rHSP90α-treated HPDE cells were trypsinized and fixed with -20°C pre-chilled 80% ethanol. After centrifugation, cell pellets were resuspended in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Permeabilized cell suspensions were further staining with 1 ml of 50 μg/ml propidium iodide plus 0.5% (w/v) RNase A. Ten minutes later, the suspensions were filtered using Falcon 12 × 75-mm polystyrene test tubes with 35-μm cell strainer Snap caps. The DNA content of cell samples was analyzed by a FACSCalibur flow cytometer with an argon laser at a 488-nm excitation (BD Biosciences).

Soft-agar colony formation assay

Two thousand HPDE cells were suspended in 1 ml of culture medium containing 0.3% agar plus PBS or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α and seeded into 6-well dishes pre-coated with 1 ml of 0.6% agar per well. These cells were incubated 21 days at 37°C, 5% CO2 for the formation of cell colonies. Colonies (composed of ≥80 cells) were counted after Giemsa staining under the Olympus IX 71 inverted microscope (Center Valley, PA, USA).

Gap-junction activity assay

The dye Calcein can be transported between cells through gap junctions, and thus cellular gap-junction activity was evaluated by assaying the levels of Calcein transfer between cells.30 HPDE cells treated with PBS or 15 μg/ml of rHSP90α were trypsinized and stained with Calcein acetoxymethyl ester and DiI (Invitrogen) for use as dye-donor cells. Donor cells were then added to a monolayer of unstained untreated HPDE cells (dye-recipient cells) at a ratio of 1:10 (donor/recipient). After co-culture for 0.2 or 3 h, the monolayer was washed, trypsinized, and resuspended in PBS and immediately analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Assay of the invasive outgrowth from cell spheroids

HPDE cells, mixed with culture medium plus 2% Matrigel (BD Biosciences), were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well of 24-well dishes pre-coated with 250 μl of Matrigel. Fresh 2% Matrigel-supplemented medium was added every 2 days until cell spheroids formed. These cell spheroids were then treated 72 h with PBS or 15 μg/ml of rHSP90α in Matrigel-supplemented medium. Morphological (branching or budding) changes were observed under an Olympus IX 71 inverted microscope.

Cell migration and invasion assays

Time-lapse photometry was performed to assay cell migration. A monolayer of HPDE cells was wounded (through scratching) with a white tip, washed twice with PBS, and incubated at 37°C with fresh culture medium plus PBS or 15 μg/ml of rHSP90α for 24 h. The cells migrating into the wounded area were taken pictures every 10 min using a CCM-330F system (Astec Co., Fukuoka, Japan) and analyzed by the Image-Pro Plus version 5.0.2 software (MediaCybernetics Inc., Silver Spring, MD, USA). To assay cell invasiveness, HPDE cells treated 24 h with PBS or 15 μg/ml of rHSP90α were suspended in 0.5% FBS-containing culture medium and seeded into the top chambers of Transwell inserts pre-coated with 5-fold diluted Matrigel. Cells were allowed to migrate for 16 h through the Matrigel toward the bottom chambers containing culture medium plus 10% FBS. The filters of the Transwell inserts were then fixed and stained with Giemsa. Invasive cells on the filters were imaged and quantified by the Image-Pro Plus software.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed independently at least three times. All data were calculated as mean ± SD and statistical significance was determined with two-tailed Student's t-tests. Groups were considered significantly different when P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This study was supported by National Health Research Institutes Grants CA-104-PP-10, CA-105-PP-10, and CA-106-PP-10 and Ministry of Science and Technology Grant MOST 106-2314-B-400-025-MY3, Taiwan, Republic of China.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2016; 66:7–30; doi: 10.3322/caac.21332 PMID:26742998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hruban RH, van Mansfeld AD, Offerhaus GJ, van Weering DH, Allison DC, Goodman SN, Kensler TW, Bose KK, Cameron JL, Bos JL. K-ras oncogene activation in adenocarcinoma of the human pancreas. A study of 82 carcinomas using a combination of mutant-enriched polymerase chain reaction analysis and allele-specific oligonucleotide hybridization. Am J Pathol 1993; 143:545–54; PMID:8342602. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moskaluk CA, Hruban RH, Kern SE. p16 and K-ras gene mutations in the intraductal precursors of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 1997; 57:2140–3; PMID:9187111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, Mankoo P, Carter H, Kamiyama H, Jimeno A et al.. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science 2008; 321:1801–6; doi: 10.1126/science.1164368 PMID:18772397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, Ross S, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Hitt BA et al.. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell 2003; 4:437–50; doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00309-X PMID:14706336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguirre AJ, Bardeesy N, Sinha M, Lopez L, Tuveson DA, Horner J, Redston MS, DePinho RA. Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev 2003; 17:3112–26; doi: 10.1101/gad.1158703 PMCID:PMC305262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herreros-Villanueva M, Hijona E, Cosme A, Bujanda L. Mouse models of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18:1286–94; doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1286 PMID:22493542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hruban RH, Goggins M, Parsons J, Kern SE. Progression model for pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2000; 6:2969–72; PMID:10955772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi C, Hong SM, Lim P, Kamiyama H, Khan M, Anders RA, Goggins M, Hruban RH, Eshleman JR. KRAS2 mutations in human pancreatic acinar-ductal metaplastic lesions are limited to those with PanIN: implications for the human pancreatic cancer cell of origin. Mol Cancer Res 2009; 7:230–6; doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0206 PMCID:PMC2708114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanagisawa A, Ohtake K, Ohashi K, Hori M, Kitagawa T, Sugano H, Kato Y. Frequent c-Ki-ras oncogene activation in mucous cell hyperplasias of pancreas suffering from chronic inflammation. Cancer Res 1993; 53:953–6; http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/canres/53/5/953.full.pdf PMID:8439969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funahashi H, Satake M, Dawson D, Huynh NA, Reber HA, Hines OJ, Eibl G. Delayed progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia in a conditional Kras(G12D) mouse model by a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. Cancer Res 2007; 67:7068–71; doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0970 PMID:17652141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turley SJ, Cremasco V, Astarita JL. Immunological hallmarks of stromal cells in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15:669–82; doi: 10.1038/nri3902 PMID:26471778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leek RD, Lewis CE, Whitehouse R, Greenall M, Clarke J, Harris AL. Association of macrophage infiltration with angiogenesis and prognosis in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Res 1996; 56:4625–9; PMID:8840975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen JJW, Yao PL, Yuan A, Hong TM, Shun CT, Kuo ML, Lee YC, Yang PC. Up-regulation of tumor interleukin-8 expression by infiltrating macrophages. Its correlation with tumor angiogenesis and patient survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9:729–37; PMID:12576442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurahara H, Shinchi H, Mataki Y, Maemura K, Noma H, Kubo F, Sakoda M, Ueno S, Natsugoe S, Takao S. Significance of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage in pancreatic cancer. J Surg Res 2011; 167:e211–9; doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.026 PMID:19765725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bingle L, Brown NJ, Lewis CE. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor progression: implications for new anticancer therapies. J Pathol 2002; 196:254–65; doi: 10.1002/path.1027 PMID:11857487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollard JW. Tumor-educated macrophages promote tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4:71–8; doi: 10.1038/nrc1256 PMID:14708027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sica A, Schioppa T, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated macrophages are a distinct M2 polarised population promoting tumor progression: potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42:717–27; doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003 PMID:16520032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liou GY, Döppler H, Necela B, Krishna M, Crawford HC, Raimondo M, Storz P. Macrophage-secreted cytokines drive pancreatic acinar-to-ductal metaplasia through NF-κB and MMPs. J Cell Biol 2013; 202:563–77; doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301001 PMID:23918941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ray KC, Moss ME, Franklin JL, Weaver CJ, Higginbotham J, Song Y, Revetta FL, Blaine SA, Bridges LR, Guess KE et al.. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor eliminates constraints on activated Kras to promote rapid onset of pancreatic neoplasia. Oncogene 2014; 33:823–31; doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.3 PMID:23376846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nozawa H, Chiu C, Hanahan D. Infiltrating neutrophils mediate the initial angiogenic switch in a mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:12493–8; doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601807103 PMCID:PMC1531646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Xu X, Shi M, Chen Y, Yu D, Zhao C, Gu Y, Yang B, Guo S, Ding G et al.. CD13hi neutrophil-like myeloid-derived suppressor cells exert immune suppression through arginase 1 expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. OncoImmunology 2017; 6:e1258504; https://doi.org/ 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1258504 PMID:28344866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trepel JB, Mollapour M, Giaccone G, Neckers L.. Targeting the dynamic Hsp90 complex in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2010; 10:537–49; doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1258504. doi: PMID:20651736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawarkar R, Sievers C, Paro R. Hsp90 globally targets paused RNA polymerase to regulate gene expression in response to environmental stimuli. Cell 2012; 149:807–18; doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.061 PMID: 22579285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W, Li Y, Guan S, Fan J, Cheng C-F, Bright AM, Chinn C, Chen M, Woodley DT. Extracellular heat shock protein-90α: linking hypoxia to skin cell motility and wound healing. EMBO J 2007; 26:1221–33; doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601579 PMID:17304217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng C-F, Fan J, Fedesco M, Guan S, Li Y, Bandyopadhyay B, Bright AM, Yerushalmi D, Liang M, Chen M et al.. Transforming Growth Factor α (TGFα)-stimulated secretion of HSP90a: using the receptor LRP-1/CD91 to promote human skin cell migration against a TGFβ-rich environment during wound healing. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28:3344–58; doi: 10.1128/MCB.01287-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu A, Tian T, Hao J, Liu J, Zhang Z, Hao J, Wu S, Huang L, Xiao X, He D. Elevation of serum HSP90α correlated with the clinical stage of non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Mol 2007; 3:107–12; http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.516.63&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Song X, Zhuo W, Fu Y, Shi H, Liang Y, Tong M, Chang G, Luo Y. The regulatory mechanism of HSP90α secretion and its function in tumor malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:21288–93; doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908151106 PMID:19965370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen JS, Hsu YM, Chen CC, Chen LL, Lee CC, Huang TS. Secreted heat shock protein 90α induces colorectal cancer cell invasion through CD91/LRP-1 and NF-κB-mediated integrin αV expression. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:25458–66; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139345 PMID:20558745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen WS, Chen CC, Chen LL, Lee CC, Huang TS. Secreted heat shock protein 90α (HSP90α) induces nuclear factor-κB-mediated TCF12 protein expression to down-regulate E-cadherin and to enhance colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:9001–10; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.437897 PMID:23386606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gopal U, Bohonowych JE, Lema-Tome C, Liu A, Garrett-Mayer E, Wang B, Isaacs JS. A novel extracellular Hsp90 mediated co-receptor function for LRP1 regulates EphA2 dependent glioblastoma cell invasion. PLoS ONE 2011; 6:e17649; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017649 PMID:21408136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolan KD, Kaur J, Isaacs JS. Secreted heat shock protein 90 promotes prostate cancer stem cell heterogeneity. Oncotarget 2017; 8:19323–41; https://doi.org/ 10.18632/oncotarget.14252 PMID:28038472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan CS, Chen WS, Chen LL, Chen CC, Hsu YT, Chua KV, Wang HD, Huang TS. Osteopontin–integrin engagement induces HIF-1α–TCF12-mediated endothelial-mesenchymal transition to exacerbate colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2018; 9:4998–5015; https://doi.org/ 10.18632/oncotarget.23578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsutsumi S, Scroggins B, Koga F, Lee MJ, Trepel J, Felts S, Carreras C, Neckers L. A small molecule cell-impermeant Hsp90 antagonist inhibits tumor cell motility and invasion. Oncogene 2008; 27:2478–87; doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210897 PMID:17968312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahn GO, Tseng D, Liao CH, Dorie MJ, Czechowicz A, Brown JM. Inhibition of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) enhances tumor response to radiation by reducing myeloid cell recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:8363–8; doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911378107 PMID:20404138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bissell MJ, Hines WC. Why don't we get more cancer? A proposed role of the microenvironment in restraining cancer progression. Nat Med 2011; 17:320–9; doi: 10.1038/nm.2328 PMID:21383745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lesina M, Kurkowski MU, Ludes K, Rose-John S, Treiber M, Klöppel G, Yoshimura A, Reindl W, Sipos B, Akira S et al.. Stat3/Socs3 activation by IL-6 transsignaling promotes progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and development of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 2011; 19:456–69; doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.009 PMID:21481788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou M, Bhatia A, Dong H, Jayaprakash P, Guo J, Sahu D, Hou Y, Tsen F, Tong C, O'Brien K et al.. Evolutionarily conserved dual lysine motif determines the non-chaperone function of secreted Hsp90α in tumour progression. Oncogene 2017; 36:2160–71; doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.375 PMCID:PMC5386837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider C, Schmidt T, Ziske C, Tiemann K, Lee KM, Uhlinsky V, Behrens P, Sauerbruch T, Schmidt-Wolf IGH, Mühlradt PF et al.. Tumour suppression induced by the macrophage activating lipopeptide MALP-2 in an ultrasound guided pancreatic carcinoma mouse model. Gut 2004; 53:355–61; doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.026005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu N, Furukawa T, Kobari M, Tsao MS. Comparative phenotypic studies of duct epithelial cell lines derived from normal human pancreas and pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1998; 153:263–9; doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65567-8 PMID:9665487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hruban RH, Volkan Adsay N, Albores-Saavedra J, Anver MR, Biankin AV, Boivin GP, Furth EE, Furukawa T, Klein A, Klimstra DS et al.. Pathology of genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic exocrine cancer: consensus report and recommendations. Cancer Res 2006; 66:95–106; doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2168 PMID:16397221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.