Synopsis

Antimicrobial resistance is a global public health threat and a danger that continues to escalate. These menacing bacteria are impacting all populations; however, until recently, the increasing trend in drug resistant infections in infants and children has gone relatively unrecognized. In this article, we highlight the current clinical and molecular data regarding infection with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in children, with an emphasis on transmissible resistance and spread via horizontal gene transfer.

Keywords: Drug Resistance, Child, Epidemiology, Infection, Bacteria, Public Health, Genetic Structures, Beta-Lactamases

Introduction to Antibiotic Resistance

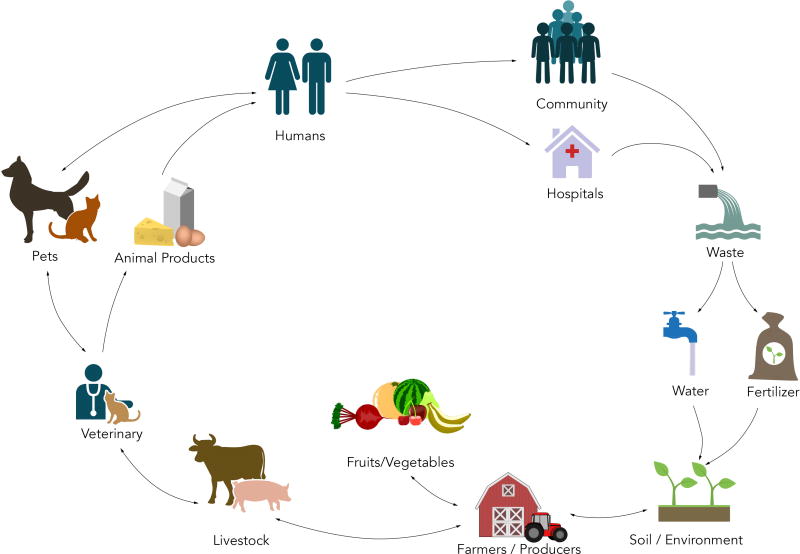

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most significant public health threats of our time. While antibiotic-resistant bacteria have existed for millions of years, these organisms were most often confined to the environment. What has led to resistance in bacteria being at the forefront of medicine over the past 70 years is the selective pressure created by the broad use of antibiotics in agriculture, livestock, veterinary and human medical practices1. The result has been an expansion of multi-drug resistant organisms (MDROs) on a global level in all people, including children, and these MDROs (predominantly gram-negative bacilli, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus sp.) are associated with significant morbidity and mortality in affected individuals 2.

This article provides a brief overview of select antibiotic-resistant bacteria, with a focus on the U.S. epidemic, and the current clinical and molecular data regarding infection with organisms known to have significant clinical impact in children.

The Genetics of Antibiotic Resistance

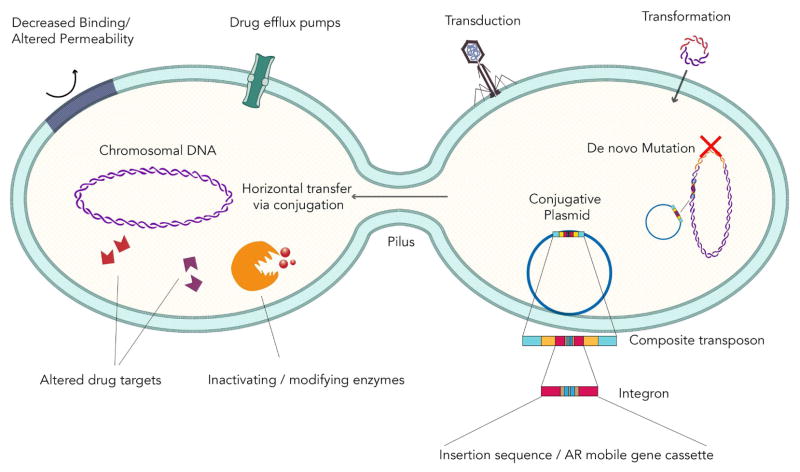

Antibiotic resistance emerged as protective survival mechanisms in environmental (soil) bacteria millions of years ago, principally as de novo nucleic acid mutations in the bacterial chromosome. Mutations can alter resistance phenotypes and remain an important mechanism of resistance in several bacterial species3. However, the current pandemic of antibiotic-resistant organisms stems from an evolution of spread occurring through horizontal gene transfer, and the acquisition of exogenous DNA encoding antibiotic resistance determinants which possess the ability to mobilize (Figure 1)3. Horizontal gene transfer occurs via three main mechanisms: transduction (via vectors such as bacteriophages), transformation (mainly by homologous recombination), and conjugation; the latter involves transfer of DNA via physical cell-to-cell contact (mating) and is the most significant contributor to the dissemination of antibiotic resistance among bacteria4, 5.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance and Horizontal Gene Transfer .

Four main systems of antibiotic resistance are highlighted: Encoding enzymes that modify or degrade antibiotics; Genes that modify the molecular targets for antibiotics; Genes that decrease permeability through cell wall or outer membrane changes; or by alterations which increase active drug efflux. The three main mechanisms of horizontal gene transfer: transduction (via vectors such as bacteriophages), transformation (mainly by homologous recombination), and conjugation; the latter involves transfer of DNA via physical cell to cell contact (mating) and is the most significant contributor to the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. The conjugative plasmid is enlarged to show the complex set of genetic elements important in transmissible resistance.

Plasmids are transmitted between organisms vertically, during bacterial division, and horizontally, and serve as the scaffold for a complex set of genetic elements important in transmissible resistance (Table 1). The classification of these extra chromosomal genetic elements containing antibiotic resistance genes has become more challenging in the wake of whole genome sequencing, which types according to phylogenetic relatedness and is able to define relatedness in the presence of multiple plasmids in organisms. However, traditional classification schemes exploit backbone loci associated with replication (replicon typing including incompatibility or Inc grouping) or plasmid mobility (MOB typing) 6.

Table 1.

| Mobile Genetic Elements and the Transmission of Antibiotic Resistance | |

|---|---|

| Element | Description |

| Plasmids | Extra-chromosomal genetic elements. Able to replicate independently of organism’s chromosome |

| Transposons | Mobile segments of nucleic acid requiring integration into the organism’s chromosome or plasmid to propagate |

| Composite Transposons | Transposon including two insertion sequences that contain information necessary for movement, and flank a segment of DNA (such as AR and conjugative genes); move as a unit |

| Insertion Sequences | Simple elements containing terminal inverted repeats and an integrase, allowing insertion into a chromosome or plasmid; reorganizes target site |

| Integrons | Segments of DNA containing an integrase for incorporation of AR genes and a promoter for expression of resistance determinants; insert into plasmids or transposons |

While plasmids have the ability to replicate independently from the organism’s chromosome, other mobile segments of nucleic acid such as transposons (aka jumping genes) must be integrated into an organism’s chromosome or a plasmid to propagate. Composite transposons, abbreviated Tn, have two insertion sequences (containing the information necessary for movement) which flank a segment of DNA (such as antibiotic resistance genes as well as conjugative genes also known as integrative and conjugative elements or ICE) and can move as a unit7. Insertion sequences are simple elements composed of terminal inverted repeats on each end and an integrase which allows the ability to insert themselves into chromosomes or plasmids and reorganize the target site. Other mobile genetic elements (MGE) important in the transfer of antibiotic resistance include integrons, which are segments of DNA inserted in plasmids or transposons, and contain an integrase important in the incorporation of antibiotic resistance gene cassettes, as well as a promoter required for expression of resistance determinants8. Integrons are organized into classes and most integrons harboring antibiotic resistance genes belong to class 19.

Specific mechanisms of antibiotic resistance may be intrinsic or acquired and are facilitated through four main systems: encoding enzymes that modify or degrade antibiotics; genes that modify the molecular targets for antibiotics; genes that decrease permeability through cell wall or outer membrane changes; or by alterations which increase active drug efflux (Figure 1). The interplay between bacterial chromosomal mutations and gene rearrangements, promiscuous plasmids moving freely between genera, and the clonal expansion of pathogenic strains has resulted in efficient transmission of antibiotic resistance genes, and has led to the rapid and sustained dissemination of MDR bacteria in the community and in healthcare settings (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Chain of Transmission of Antibiotic Resistance.

Antibiotic resistance at the human–animal–environment interface is exceptionally complex. The driver of antibiotic-resistance in bacteria is mainly due to the selective pressure created by the broad use of antibiotics in agriculture, livestock, veterinary and human medical practices. With a continuum of transmission routes and vehicles of resistance, each reservoir of resistance serves a perpetual source for antibiotic-resistant bacteria into the other reservoirs within the chain of transmission.

Overview on the Epidemiology of Antibiotic Resistance in Gram-Positive Bacteria

Staphylococcus aureus

Strains of S. aureus resistant to methicillin (MRSA) were first recognized as a clinical threat in adult patient populations in the 1960s. MRSA infections were relatively uncommon in the pediatric population until the 1990s, when infections (primarily skin and soft tissue) were noted in adults and children without prior healthcare contact10, and strains were subsequently named community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA). As CA-MRSA infections increased, healthcare-associated (HA-MRSA) infections continued to burden hospitalized patients, resulting in divergent epidemiology of MRSA infections in healthcare settings. During the early period of the community epidemic, HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA strains were separate entities; however, recent molecular analyses of patients with MRSA infections has shown that CA-MRSA strains are now a common cause of MRSA infections acquired in healthcare settings, blurring the distinction11.

With both CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA, the main alteration conferring resistance is a single penicillin-binding protein (labeled PBP2a), encoded by the mec gene12. PBPs are located on bacterial cell surface, and catalyze transglycosylation and transpeptidation thereby providing protection12. The mec gene is located on a MGE referred to as the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) genetic element, and to date at least 11 SCCmec types have been reported. HA-MRSA strains often have gene cassettes conferring resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics, thereby limiting therapy to more expensive antibiotics and/or those with more concerning safety profiles. In North America, HA-MRSA strains classically feature SCCmec types I–III, while CA-MRSA commonly feature SCCmec type IV.

To further differentiate the epidemiology of circulating MRSA strains, bacterial nomenclature organizes MRSA into clonal complexes based on DNA fingerprint patterns by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. CA-MRSA strains in North America commonly belong to the USA300 group, and HA-MRSA more commonly belong to the USA100 and USA800 groups13. USA300 strains often have a smaller amount of genetic material in their SCCmec sequences, which allow for low-cost replication and ease of dissemination of genetic material to susceptible isolates. As a result, USA300 strains have great potential to cause significant resistant and invasive infections14.

Studies regarding CA-MRSA in U.S. children generally highlight the rapid increase in infections from the mid-1990s until 2005–2006, with a subsequent decrease in infection rates therafter15. However, there is significant geographic variation, and while both pediatric HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA rates have mostly stabilized, some regions have noted continued increases in CA-MRSA infection16,17,18.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) and clindamycin are often used in the treatment of CA-MRSA; and while resistance to TMP/SMX has remained relatively uncommon, clindamycin resistance in both CA-MRSA and methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) has increased over the past decade. A recent study from the U.S. Military Health System found CA-MRSA clindamycin resistance increased from 9.3% in 2005 to 16.7% in 201415. Similar increases in MSSA clindamycin resistance have been reported19.

To help eradicate MRSA carriage and control spread, infection prevention measures involve the application of mupirocin ointment into the anterior nares, often in conjunction with chlorhexidine baths to further reduce colonization burden. While decolonization campaigns have successfully reduced MRSA infection rates, resistance to mupirocin and chlorhexidine have begun to emerge. The increase in mupirocin resistance is primarily facilitated by the plasmid-based mupA gene, which confers resistance by encoding a novel RNA synthetase. Chlorhexidine resistance genes, known as qacA/B, are also plasmid-mediated and encode efflux pumps. Studies of pediatric mupirocin resistance rates range from 2% in isolates in St. Louis and the northwestern U.S., to 19% of MRSA isolates in the southern U.S.20, 21. MRSA resistance to chlorhexidine remains uncommon. Resistance to chlorhexidine was approximately 1% in an outpatient pediatric study in St. Louis20.

Streptococcus pyogenes

Streptococcus pyogenes clinical isolates are universally susceptible to penicillin; however, macrolides are occasionally used to treat infections, particularly in patients with severe penicillin allergy. Macrolide-resistant strains of S. pyogenes emerged in the clinical setting in the 1980s, as a result of selective pressure following a dramatic increase in the prescription of macrolides for upper respiratory infections22,23. Two main mechanisms of macrolide resistance are employed by S. pyogenes. The first mechanism involves methylation of the 23S ribosomal RNA by erm genes which causes co-resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin (MLS) antibiotics (MLS phenotype). MLS resistance may be constitutive (MLSc) or inducible (MLSi). The second, and more common mechanism, is an active efflux pump related to enzymes encoded for by mef genes (M phenotype). M and MLS phenotypes are often distinguished by using double-disk diffusion testing (D-test) evaluating clindamycin (lincosamide) susceptibility in the presence of erythromycin resistance22,23.

In the U.S., current resistance to macrolides has been estimated at approximately 5%, which is a two-fold increase compared to 1990s. The clinical significance of this resistance has become apparent, as there have been cases of children treated with macrolides for S. pyogenes pharyngitis who went on to develop acute rheumatic fever22, 23. Overall, macrolide resistance in pediatric S. pyogenes isolates differs drastically geographically, from reported rates of 2.6% in Germany to as high as 95% in studies of Chinese children 23. Correspondingly, the prevalence of macrolide resistance appears to correlate with regional utilization rates of macrolides.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Similar to S. aureus, S. pneumoniae confers resistance to penicillins through PBPs. However, unlike MRSA where resistance is primarily due to dissemination of clonal strains, circulating penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae are much more heterogeneous24. Like S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae is able to express the M and MLS phenotypes conferring resistance to macrolides and clindamycin25.

Internationally, penicillin and macrolide resistance were increasing at the turn of the 21st century. However, infection rates overall and with penicillin-resistant serotypes significantly decreased following the introduction of pneumococcal vaccines. Early U.S. studies noted an initial decrease in pneumococcal activity after the introduction of 7-valent vaccine (PCV7)26, with residual high resistance by serotypes not covered by PCV7. The 13-valent vaccine (PCV13) coverage of serotype 19A led to a decrease in one of the most pathogenic (and resistant) circulating serotypes, and since 2010, there has been an overall downward trend in non-susceptible invasive pneumococcal infections. Regional differences in circulating antibiotic-resistant S. pneumoniae remain; however, this resistance does not appear related to a dominant non-vaccine serotype27.

Enterococcus species

Antibiotic resistance in Enterococcus species (E. faecalis and E. faecium) became a significant problem in healthcare settings during the 1980s, when the organisms began displaying high level resistance to vancomycin. Genes responsible for vancomycin resistance (known as van genes) are located on plasmids and/or transposons, and alter the peptidoglycan synthesis pathway. Enterococcus isolates are notoriously hardy organisms, withstanding conventional cleaning methods and are able to survive on surfaces for several days. This has led to the spread of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) in healthcare settings28.

While VRE remain stable residents of adult intensive care units (ICUs), these resistant organisms have increased in pediatric inpatient settings. A study of VRE in U.S. children described VRE rates of 53 cases per million in 1997 which increased to 120 cases per million by 2012. The majority of affected children had a history of prolonged healthcare and antibiotic exposures 28.

Notable Antibiotic Resistance in Atypical Organisms

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Since the turn of the century, there has been an increase in reports of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. Resistance to macrolides is due to a point mutation in the 23S ribosome, which leads to poor antibiotic binding.

Resistance trends in M. pneumoniae isolates differ globally. In Asian countries where macrolides are commonly prescribed, Mycoplasma resistance to macrolides may be as high as 90%29. Macrolide resistance in M. pneumoniae has remained relatively low in the U.S., although resistance may be on the rise. A recent study examining M. pneumoniae isolates from 6 U.S. centers caring for children found macrolide resistance rates to be approximately 13%30 The treatment of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma infections often involves tetracyclines or quinolones, which have limited indications in children due to side effect profiles. Therefore, surveillance of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae may become increasingly important.

Overview of the Epidemiology of Antibiotic Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria

Fluoroquinolone Resistance

Resistance to fluoroquinolone antibiotics (FQR) is commonly mediated by mutations in the genes encoding gyrase or topoisomerase enzymes (gyrA/parC), alteration in porins, and efflux pumps. This is mainly chromosomally-based resistance in the non-lactose fermenting gram-negative bacilli (GNB) such as Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter species. FQR genes can be carried on plasmids (PMFQR) and is common to Enterobacteriaceae. PMFQR is associated with agricultural and veterinary use of antibiotics, and mechanisms include acetyltransferases, efflux pumps, and pentapeptide proteins. FQR may be high-level in isolates where PMFQR and chromosomal mechanisms are both present31.

There is a paucity of data regarding FQR GNB infections in the pediatric population, and while quinolones are not commonly used in younger children, FQR is still a problem as they are prescribed in adolescents, for MDR GNB infections, and for the treatment of select conditions. Available data suggests that FQR in GNB ranges between 5–14% at major U.S. medical centers32. Moreover, this uptrend maybe reflective of increasing PMFQR in MDR Enterobacteriaceae recovered from children nationally and globally33,34. Studies from Asia have noted significant PMFQR in Enterobacteriaceae infections in children, ranging from 10% in Korea to 23% in China with an increase in prevalence over time35,36.

Beta-lactam Resistance

Among the first noteworthy pediatric clinical impacts of beta-lactam resistance due to β-lactamases (enzymes that breakdown β-lactams) in GNB was the recognition of ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in 197437.

Since that time, the increase in β-lactam usage and introduction of broad-spectrum β-lactams has been met with continued adaptations in GNB, where the number of β-lactamase genes (encoding β-lactamases) in GNB has now surpassed 2,1009, 42. Originally these β-lactamase genes were narrow spectrum and chromosomally-based; however, the current pandemic of β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ENT) is due to the rapid increase in transmissible ESBL and carbapenemase genes.

β-lactamase genes are organized into two classification systems based on their amino acid motifs (structure) in the Ambler classification and by their substrate and inhibitor functions in the Bush-Jacoby-Medeiros classification system (Table 2). Organisms carrying ESBL genes were first recognized in 1983 in Germany, when a single nucleotide polymorphism resulted in a transferable SHV gene40. SHV- and TEM-type ESBL harboring GNB were the main source of transmissible β-lactam resistance until the emergence of CTX-M-type ESBLs in the mid-1990s. These CTX-M carrying bacteria were found in healthcare settings but also in persons without significant healthcare exposure, which led to the label of CTX-M as the “community-acquired ESBL”. The CTX-M pandemic is mainly associated with a clonal lineage of E. coli (known as ST131). These clonal strains, in particular the clade C, ST131-H30 E. coli strains, are MDR, and harbor additional plasmids yielding resistance to aminoglycosides, TMP/SMX, and fluoroquinolones. Transmissible AmpC resistance remains much less common than ESBLs in clinical GNB isolates, and is most commonly CMY-241. However, other plasmid-based AmpC have been found in Enterobacteriaceae recovered from children46.

Table 2.

| Classification Schema of Beta-Lactamase Genes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambler Class | A | B | C | D |

| Bush-Jacoby Classification | 2a, 2b, 2be, 2br, 2ber, 2c, 2ce, 2e, 2f | 3a, 3b | 1, 1e | 2d, 2de, 2df |

| Notable Enzyme Types | ESBLs – TEM, SHV, CTXM, PER,

VEB Carbapenemases – KPC |

Carbapenemases — IMP,VIM, NDM | AmpC Cephalosporinases – CMY, DHA, FOX, ACT, MIR | ESBLs – OXA Carbapenemases – OXA |

Abbreviations: ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; IMP, active on imipenem metallo-β-lactamase; KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase; NDM, New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase; OXA, oxacillin-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase; VIM, Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase

Carbapenemases are categorized by their molecular structures and belong to Ambler classes A, B or D42,43. Class A and D carbapenemases require serine at their active site while Class B, the metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs), require zinc for β-lactam hydrolysis. MBL activity is inhibited by metal-chelating agents such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)42, 44.

Most notable of the Class A carbapenemases are the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPC), and strains harboring KPC genes commonly have acquired resistance to multiple (>3) antibiotic classes making them MDROs45. The global spread of KPC-Ent is primarily due to clonal expansion of strains of K. pneumoniae belonging to clonal complex 258 and, more specifically, ST258 strains harboring a KPC-2 or KPC-3 gene found on a Tn3-based transposon, Tn440139. However, the propagation of KPC genes is much more complex, and the major circulating ST258 K. pneumoniae strains comprise two distinct genetic clades (I and II). Additionally, strains of multiple sequence types have been associated with KPC carriage and are linked to a diverse group of plasmids39,45, 46. The Class D OXA β-lactamases are a heterogeneous group of enzymes found in Acinetobacter spp. and increasingly, in Enterobacteriaceae47. The spread of OXA-48-producing Enterobacteriaceae is most commonly associated with an IncL/M-type plasmid with integration of the OXA-48 gene through the acquisition of a Tn1999 composite transposon47,48.

The Class B metallo-β-lactamases are a complex group, and notable transmissible MBL genes include IMP (active on imipenem), NDM (New-Delhi MBL), and VIM (Verona integron-encoded MBL)39,45. VIM-type and IMP-type MBLs are often embedded in Class 1 integrons and are associated with plasmids or transposons which enable spread49. The NDM-type MBL are of major global concern as they have widely disseminated in Enterobacteriaceae in less than a decade. It has been theorized that the most common circulating NDM MBL gene (NDM-1) evolved from Acinetobacter baumannii50. NDM-type MBL genes have been found in multiple epidemic clones, and it is thought that the rapid and dramatic dissemination of NDM MBLs is facilitated by the genetic elements’ bacterial promiscuity39.

The Clinical Impact of Antibiotic Resistance in GNB, by Organism

Acinetobacter species

Acinetobacter are a complex genus of very resilient organisms that are resistant to desiccation, and thereby survive on dry surfaces for several months51. The major driver of poor outcomes in Acinetobacter infections is antibiotic resistance, and A. baumannii harbor a major resistance genomic island comprised of 45 resistance genes, facilitating resistance to multiple antibiotic classes53. Beta-lactam resistance is due to multiple mechanisms including chromosomal, plasmid- or transposon-encoded β−lactamases, and this, in combination with active efflux systems, reduced outer membrane proteins, the absence of PBP2, and transposon-mediated aminoglycoside, sulfonamide, tetracycline resistance mechanisms have resulted in a perfect storm of highly resistant bacterial populations reported globally39.

In the pediatric population, most of the published literature on A. baumannii infections are single-centered, cohort studies and report that risk factors include solid malignancy, renal disease, and male gender52. Though patients with A. baumannii infections are commonly hospitalized, infections may develop in the outpatient setting in children with central lines or receiving at home ventilator care52.

In adults, carbapenem-resistant (CR) A. baumannii (CRAB) is increasing and has been linked to OXA genes. There is limited data on pediatric CRAB; however, in children, this CR phenotype may be most often due to a combination of intrinsic resistance mechanisms and selection pressure. This is based on unpublished data on trends of A. baumannii infections in U.S. children between 1999 and 2012 which found that most CRAB isolates from children were typically not MDR, which is often the case for OXA-harboring CRAB (personal communication, L. Logan). An alternate possibility is that A. baumannii recovered from children actually represent another species of less virulent Acinetobacter, as until recently it was difficult for microbiology labs to differentiate A. baumannii from A. calcoaceticus53.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Similar to Acinetobacter species, P. aeruginosa often feature multiple resistance mechanisms and are able to survive in harsh environments. P. aeruginosa have resistance mechanisms that include intrinsic, chromosomally encoded β-lactamase enzymes, quorum-sensing proteins, efflux pumps, structural topoisomerase mutations, porin alterations and reduced outer membrane permeability53,54. The acquisition of MGE that harbor genes encoding for carbapenemases, aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, and FQR determinants additionally contribute to the expression of MDR phenotypes among isolates53.

A recent analysis of over 87,000 non-Cystic Fibrosis P. aeruginosa isolates recovered from U.S. children ages 1–17 years was notable for an increase in MDR P. aeruginosa from 15.4% to 26% between 1999–2012. Additionally, carbapenem resistance increased from 9.4% to 20%. The study noted that both MDR and CR infections were more common in the ICU setting, among children aged 13 to 17 years, in respiratory specimens, and in the West North Central region. Of added concern, resistance to other antibiotic classes (aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and piperacillin-tazobactam) also increased during the study period54. As with Acinetobacter infections, these data emphasize the importance of aggressive infection prevention strategies and Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASP) to help combat antimicrobial resistance.

Enterobacteriaceae

In this section, we focus on the etiology of increasing beta-lactam resistance in Enterobacteriaceae, and the challenges clinicians face as relates to these emerging threats.

Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae

In the U.S., the prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-Ent) infections in the pediatric population has dramatically increased in the last decade, and is related to the current pandemic of ESBL-Ent infections due to the dissemination of MDR ST131 CTX-M-producing E. coli strains50, 46.

The acquisition of ESBL-Ent significantly varies by region, age, healthcare exposure, organism, and ESBL genotype. In healthcare settings, international studies describe an increase in ESBL-Ent colonization and infection in the neonatal population, and younger gestational age, prolonged mechanical ventilation, low birth weight, and antibiotic use are risk factors for infection in this population55. However, U.S. data suggest that the highest pediatric age risk group is 1 to 5 years56. Outside of the neonatal period, risk factors for ESBL-Ent infections are more similar to the adult population, and include antibiotic exposure, chronic medical conditions, healthcare exposure and recurrent infections57,59. Neurologic conditions may be a risk factor unique to children9. A majority of published data, however, have not differentiated risk factors for ESBL-Ent infection by genotype34,58.

AmpC Cephalosporinase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae

In a study of four pediatric medical centers in three U.S. regions, AmpC genes were present in 29% of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant (ESC-R) E. coli and Klebsiella sp. isolates, and 87% of the AmpC phenotype was due to presence of a CMY-2 gene. Most CMY-2-producing isolates were recovered from the West region59. This contrasted to findings in a six-center Chicago area study, where the prevalence of AmpC genes in ESC-R isolates from children was 14.2%, and the ACT/MIR-type AmpC genes predominated (78%) 78.

Carbapenem Resistance in Enterobacteriaceae

GNB that feature resistance to carbapenems typically accomplish resistance in one of two ways: structural mutations (alteration of porins) along with the production of other β-lactamases (such as ESBL or AmpC), or by producing carbapenemases39.

Risk factors for CRE infection in children include medical comorbidities, prolonged hospitalizations, immunosuppression, and prior antibiotic use60. These data are mainly from small studies of critically ill and immunosuppressed patients in the pediatric ICU or transplant units61,62. Moreover, most pediatric studies of CRE have used phenotypic data to assess risk factors, and mechanistic data is scant. A recent multi-centered case-case-control study of KPC-Ent in Chicago children found specific factors associated with KPC-Ent infection included pulmonary and neurologic comorbidities, GI and pulmonary devices, and exposure to carbapenems and aminoglycosides. The majority of strains available for genotyping were non-ST258 KPC-Ent strains, which differs from adults63.

At the turn of the 21st century, CRE infections in the U.S. were relatively rare in the pediatric population. However, an analysis examining over 300,000 Enterobacteriaceae isolates from children ages 0–18 years noted an increase in CRE over time. In 1999–2000, there were zero pediatric CRE infections, which rose to 0.47% by the end of the study period in 2011–201264. The largest increase occurred in Enterobacter species, which increased from 0% being CRE in 1999 to 5.2% in 2012, followed by Klebsiella sp. and E. coli, which increased from 0% to 1.7% and 0.14% CRE respectively. The prevalence of MBL-Ent considerably varies by region, and countries such as India have a high prevalence of NDM-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections in neonates and children. Recently, MBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae have emerged in U.S. children. These data are alarming as several children, especially infants, were found to be silently colonized with these organisms, and studies have shown that children may remain colonized with MDR Enterobacteriaceae for months to years65,66.

Controlling the Spread of CRE in Pediatric Healthcare Settings

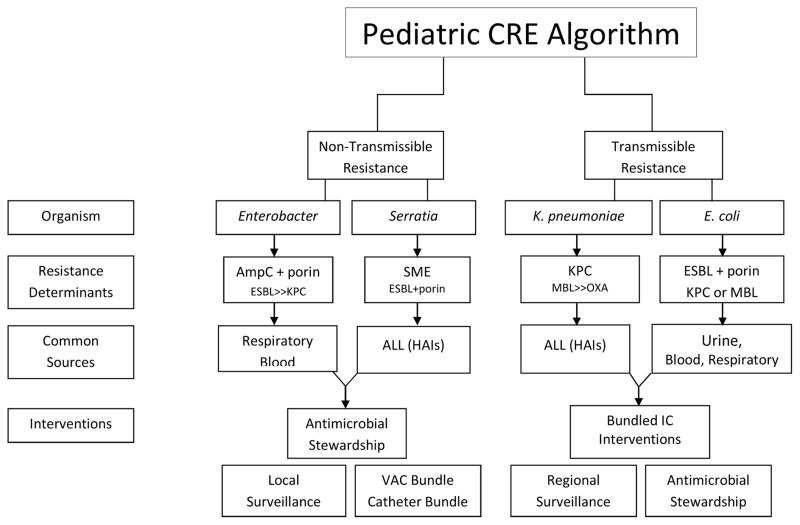

The importance of understanding the genetic background in CRE isolates cannot be underscored; yet, most clinical laboratories do not have the capability of genotyping isolates in real-time to affect clinical practice. Because of this, there is a need for CRE prevention guidance utilizing phenotypic data. Herein, we propose a conceptual algorithm to aid in the decision process for managing CRE in the U.S. pediatric healthcare setting (Figure 3). It is important to note that in the discussion of transmissible resistance, the reference is person-to-person rather than organism-to-organism transmission. It is also important to emphasize that bacteria do not follow algorithms, and may have both transmissible and non-transmissible elements contributing to their resistance phenotype.

Figure 3. Controlling the Spread of CRE in Pediatric Healthcare Settings – A Conceptual Algorithm.

Size of text in each box represents the relative amount or frequency of the element.

Abbreviations: CRE, Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae; K. pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae; AmpC, AmpC Cephalosporinases; ESBL, Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamases; Porin, Outer Membrane Porin Channel Alteration; SME, Serratia marcescens enzyme; KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase; MBL, Metallo-Beta-Lactamase; OXA, Oxacillin-hydrolyzing Beta-Lactamase; ALL, All sources; HAIs, Healthcare-Associated Infections; IC, Infection Control; VAC, Ventilator-Associated Complication; Catheter Bundle, aimed at reducing device-related infections.

Using pediatric data, a potential way to distinguish transmissible versus non-transmissible CR is by organism. For non-transmissible CRE, the most common organism is Enterobacter, and the CR phenotype is due to expression of a chromosomal AmpC cephalosporinase in combination with a porin channel alteration60. However, Enterobacter may harbor transmissible ESBL and/or carbapenemase genes, though this is less common. Common sources for CR Enterobacter are the respiratory tract, and secondarily from blood, typically in children located in the ICU64. CR Serratia marcescens most often are expressing a chromosomally-based carbapenemase known as Serratia marcescens enzyme (SME) and cause healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in critically ill patients67. CRE infections due to non-transmissible resistance mechanisms are frequently related to antibiotic usage and resultant selection pressure, and risk factors include mechanical ventilation and devices. Therefore, interventions should focus on Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASPs) and targeted bundle interventions, such as a ventilator-associated complication bundle and reducing device-related infections68,69. Molecular characterization and surveillance is critical at the local level, because increases in CRE, particularly if focused in certain units or patient populations, may be due to transmissible resistance mechanisms.

With transmissible resistance and CPE, the most common organism is Klebsiella pneumoniae. The most common carbapenemase gene in the U.S. is KPC, and infection most often occurs in a child who is critically ill and/or has chronic comorbidities60. However, MBL-Ent and OXA-Ent have been recovered from U.S. children, and maybe associated with outbreaks or travel to endemic regions39,65. E. coli is the second most common organism to harbor carbapenemases; however, the CR phenotype in E. coli may also be due to a transmissible ESBL or AmpC gene in combination with a porin mutation. CP and ESBL E. coli are most often from urinary sources. For CPE, the focus is on halting spread. Therefore, bundled infection control (IC) interventions are critical. Additionally, studies have shown that ASP in combination with bundled IC interventions can further reduce CPE colonization and infection70. Antibiotics, especially those that disturb the anaerobic microflora and/or lacking significant activity against CPE are thought to promote intestinal CPE colonization and prolong carriage71. Lastly, in hospitals with significant rates of CPE, local and regional surveillance, along with interfacility communication, is of great importance in controlling spread72.

Emerging Threats

Colistin Resistance

In children, reports of side effects of polymixins (polymixin B and colistin) are relatively high, with 22% of children experiencing nephrotoxicity and 4% experienced neurotoxicity in a multi-centered, pediatric case-series73. Because of this, polymixins are reserved for use in MDR GNB infections, and after less toxic options have been exhausted.

Resistance to polymixins is mainly chromosomal-based, and is associated with mutations in the PmrAB or PhoPQ two-component systems, or with alterations of the mgrB gene74. However, in 2016, the first reports of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae (known as mcr-1) were published, and the mcr-1 gene was associated with multiple plasmid backbones75. Colistin therapy has been used for agricultural and veterinary purposes for many years, and resistance has been linked to animal sources. To date, three mobile colistin resistance genes have been detected (mcr-1 to mcr-3), mainly in E. coli76. Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance in the pediatric population is thought to be rare, with only single reports of children colonized with plasmid-mediated colistin-resistant E. coli recovered from stool samples in China77.

Conclusions

Antibiotic resistance in bacteria continues to evolve and represent an ever-increasing danger in all populations, including children. Recognition of this global public health threat through molecular and clinical epidemiologic studies, along with dedicated surveillance, may allow for timely strategies in prevention and treatment. Opportunities to mitigate spread of these dangerous organisms are numerous, and multi-faceted approaches should focus on education and training, bundled infection prevention measures, antibiotic stewardship programs, and addressing modifiable risk factors for infection. A heightened awareness and targeted resources by national and international programs, especially those dedicated to the health of children, are essential to halt the spread of these menacing pathogens in our most vulnerable population.

Key Points.

Antimicrobial resistance is a significant public health threat and a global crisis. Infections with antibiotic-resistant organisms are associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Antibiotic-resistant infections are increasing in children nationally and globally. This is primarily due to the selective pressure created by the broad use of antibiotics.

Understanding the mechanisms that lead to antimicrobial resistance is critical in the development of strategies for infection prevention and control of spread.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was directly supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health [grant K08AI112506 to L.K.L.].

We thank Mr. Sworup Ranjit for creation of the illustrations. We would like to thank Dr. Robert A. Weinstein for thoughtful comments. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no disclosures relevant to this article.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.White DG, Zhao S, Sudler R, et al. The isolation of antibiotic-resistant salmonella from retail ground meats. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1147–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toleman MA, Walsh TR. Combinatorial events of insertion sequences and ICE in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:912–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodford N, Ellington MJ. The emergence of antibiotic resistance by mutation. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:5–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balcazar JL. Bacteriophages as vehicles for antibiotic resistance genes in the environment. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004219. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domingues S, Nielsen KM, da Silva GJ. Various pathways leading to the acquisition of antibiotic resistance by natural transformation. Mob Genet Elements. 2012;2:257–60. doi: 10.4161/mge.23089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orlek A, Stoesser N, Anjum MF, et al. Plasmid classification in an era of whole-genome sequencing: application in studies of antibiotic resistance epidemiology. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:182. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Partridge SR. Analysis of antibiotic resistance regions in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:820–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahillon J, Chandler M. Insertion sequences. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:725–74. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.725-774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherry J, Demmler-Harrison GJ, et al. Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 8. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herold BC, Immergluck LC, Maranan MC, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children with no identified predisposing risk. JAMA. 1998;279:593–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popovich KJ, Weinstein RA, Hota B. Are community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains replacing traditional nosocomial MRSA strains? Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:787–94. doi: 10.1086/528716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauvage E, Kerff F, Terrak M, et al. The penicillin-binding proteins: structure and role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:234–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, et al. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:603–61. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thurlow LR, Joshi GS, Richardson AR. Virulence strategies of the dominant USA300 lineage of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;65:5–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00937.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutter DE, Milburn E, Chukwuma U, et al. Changing susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus in a US pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153099. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David MZ, Daum RS, Bayer AS, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia at 5 US academic medical centers, 2008–2011: significant geographic variation in community-onset infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:798–807. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwamoto M, Mu Y, Lynfield R, et al. Trends in invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e817–e824. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logan LK, Healy SA, Kabat WJ, et al. A prospective cohort pilot study of the clinical and molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus in pregnant women at the time of group B streptococcal screening in a large urban medical center in Chicago, IL. Virulence. 2013;4:654–658. doi: 10.4161/viru.26435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandra S, Braykov N, Laxminarayan R. Is methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) sequence type 398 confined to Northern Manhattan? Rising prevalence of erythromycin- and clindamycin-resistant MSSA clinical isolates in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:306–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fritz SA, Hogan PG, et al. Mupirocin and chlorhexidine resistance in Staphylococcus aureus in patients with community-onset skin and soft tissues infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:559–68. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01633-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNeil JC, Hulten KG, Kaplan SL, et al. Mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus causing recurrent skin and soft tissue infections in children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2431–3. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01587-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green MD, Deall B, Marcon MJ, et al. Multicentre surveillance of the prevalence and molecular epidemiology of macrolide resistance among pharyngeal isolates of group A Streptococci in the USA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:1240–3. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Logan L, McAuley J, Shulman S. Macrolide treatment failure in Streptococcal pharyngitis resulting in acute rheumatic fever. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e798–802. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hakenbeck R, Briese T, Chalkley L, et al. Antigenic variation of penicillin-binding proteins from penicillin-resistant clinical strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:313–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephens DS, Zughaier SM, Whitney CG, et al. Incidence of macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae after introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: population-based assessment. Lancet. 2005;365:855–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanz RR, Shulman ST, Shortridge VD. Community-based surveillance in the United States of macrolide-resistant pediatric pharyngeal group A Streptococci during 3 respiratory disease seasons. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(12):1794–801. doi: 10.1086/426025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomczyk S, Lynfield R, Schaffner W, et al. Prevention of antibiotic-nonsusceptible invasive pneumococcal disease with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1119–25. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams DJ, Eberly MD, Goudie A, Nylund CM. Rising vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus infections in hospitalized children in the United States. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6:404–11. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer Sauteur PM, van Rossum AM, Vink C. Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children: carriage, pathogenesis, and antibiotic resistance. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27:220–7. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng X, Lee S, Selvarangan R, et al. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1470–2. doi: 10.3201/eid2108.150273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawkey PM. Mechanisms of quinolone action and microbial response. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(Suppl 1):29–35. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson MA, Schutze GE Committee on infectious diseases. The use of systemic and topical fluoroquinolones. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20162706. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logan LK, Hujer AM, Marshall SM, et al. ASM Microbe 2016. Boston, MA: Fluoroquinolone Resistance (FQR) Mechanisms in Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae (Ent) Isolates from Children. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medernach RL, Rispens JR, Marshall SH, et al. ASM Microbe. New Orleans, LA: 2017. Resistance Mechanisms and Factors associated with Plasmid-Mediated Fluoroquinolone Resistant (PMFQR) Enterobacteriaceae (Ent) Infections in Children. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xue G, Li J, Feng Y, et al. High prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from pediatric patients in China. Microb Drug Resist. 2017;23:107–114. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2016.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim NH, Choi EH, Sung JY, et al. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes and ciprofloxacin resistance in pediatric bloodstream isolates of Enterobacteriaceae over a 9-year period. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2013;66:151–4. doi: 10.7883/yoken.66.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomeh MO, Starr SE, McGowan JE, Jr, et al. Ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae type B infection. JAMA. 1974;229:295–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bush K. ASM Microbe. Boston, MA: 2016. Top 10 Beta-lactamase Papers for 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Logan LK, Weinstein RA. The epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: The impact and evolution of a global menace. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:S28–S36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:657–86. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lukac PJ, Bonomo RA, Logan LK. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in children: old foe, emerging threat. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1389–97. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bush K, Jacoby GA. Updated functional classification of beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:969–76. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01009-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ambler RP. The structure of beta-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1980;289:321–31. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel G, Bonomo RA. “Stormy waters ahead”: global emergence of carbapenemases. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:48. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:228–36. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen L, Mathema B, Pitout JD, et al. Epidemic Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 is a hybrid strain. mBio. 2014;5:e01355–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01355-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P. Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:24–38. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01512-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poirel L, Bonnin RA, Nordmann P. Genetic features of the widespread plasmid coding for the carbapenemase OXA-48. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:559–62. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05289-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mojica MF, Bonomo RA, Fast W. B1-Metallo-β-Lactamases: where do we stand? Curr Drug Targets. 2016;17:1029–50. doi: 10.2174/1389450116666151001105622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Worldwide dissemination of the NDM-type carbapenemases in Gram-negative bacteria. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:249856. doi: 10.1155/2014/249856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wendt C, Dietze B, Dietz E, et al. Survival of Acinetobacter baumannii on dry surfaces. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1394–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1394-1397.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Segal SC, Zaoutis TE, Kagen J, et al. Epidemiology of and risk factors for Acinetobacter species bloodstream infection in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:920–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3180684310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bonomo RA, Szabo D. Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(Suppl 2):S49–56. doi: 10.1086/504477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Logan LK, Gandra S, Mandal S, et al. Multidrug- and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in children, United States, 1999–2012. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016 doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw064. pii:piw064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crivaro V, Bagattini M, Salza MF, et al. Risk factors for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Serratia marcescens and Klebsiella pneumoniae acquisition in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 2007;67:135–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Logan LK, Braykov NP, Weinstein RA, Laxminarayan R CDC Epicenters Prevention Program. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in children: trends in the United States, 1999–2011. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2014;3:320–8. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zerr DM, Miles-Jay A, Kronman MP, et al. Previous antibiotic exposure increases risk of infection with extended-spectrum-β-lactamase- and AmpC-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in pediatric patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:4237–4243. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00187-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rispens JR, Medernach RL, Hujer AM, et al. IDWeek. San Diego, CA: 2017. A Multicenter Study of the Clinical and Molecular Epidemiology of TEM- and SHV-type Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase producing (ESBL) Enterobacteriaceae (Ent) Infections in Children. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zerr DM, Weissman SJ, Zhou C, et al. The molecular and clinical epidemiology of extended-spectrum cephalosporin- and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae at 4 US pediatric hospitals. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2017 doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw076. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Logan LK. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: An emerging problem in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:852–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suwantarat N, Logan LK, Carroll KC, et al. The prevalence and molecular epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae colonization in a pediatric intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1–9. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stillwell T, Green M, Barbadora K, et al. Outbreak of KPC-3 producing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a US pediatric hospital. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2015;4:330–8. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nguyen DC, Scaggs FA, Charnot-Katsikas A, et al. IDWeek. San Diego, CA: 2017. A Multicenter Case-Case-Control Study of Factors Associated with Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (KPC-CRE) Infections in Children. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Logan L, Renschler J, Gandra S, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in children, United States, 1999–2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:2014–21. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Logan LK, Bonomo RA. Metallo-β-lactamase (MBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae in United States children. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofw090. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zerr DM, Qin X, Oron AP, et al. Pediatric infection and intestinal carriage due to extended-spectrum-cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3997–4004. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02558-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Herra C, Falkiner FR. Serratia marcescens. [Accessed July 27, 2017];Antimicrobe Microbes. Available at: http://www.antimicrobe.org/b26.asp.

- 68.Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, et al. Strategies to Prevent Ventilator Associated Pneumonia in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:915–936. doi: 10.1086/677144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Priebe GP, Larsen G, Logan LK, et al. Etiologies for pediatric ventilator associated conditions – the need for a broad VAC prevention bundle. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:80. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Viale P, Giannella M, Bartoletti M, et al. Considerations about antimicrobial stewardship in settings with epidemic extend-spectrum β-lactamase-producing or carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Infect Dis Ther. 2015;4(Suppl 1):65–83. doi: 10.1007/s40121-015-0081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perez F, Pultz MJ, Endimiani A, et al. Effect of antibiotic treatment on establishment and elimination of intestinal colonization by KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2585–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00891-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Trick WE, Lin MY, Cheng-Leidig R, et al. Electronic public health registry of extensively drug-resistant organisms, Illinois, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1725–32. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.150538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tamma PD, Newland JG, Pannaraj PS, et al. The use of intravenous colistin among children in the U.S: results from a multicenter, case series. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:17–22. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182703790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Olaitan AO, Morand S, Rolain JM. Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:643. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:161–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yin W, Li H, Shen Y, et al. Novel plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-3 in Escherichia coli. mBio. 2017;8:e00543–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00543-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gu DX, Huang YL, Ma JG, et al. Detection of colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolates from an infant with diarrhea in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:5099–5100. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00476-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Logan LK, Hujer AM, Marshall SH, et al. Analysis of Beta-Lactamase Resistance Determinants in Enterobacteriaceae from Chicago Children: a Multicenter Survey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016 May 23;60(6):3462–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00098-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]