Abstract

Human neutrophil elastase (HNE) is an important target for the development of novel and selective inhibitors to treat inflammatory diseases, especially pulmonary pathologies. Here, we report the synthesis, structure–activity relationship analysis, and biological evaluation of a new series of HNE inhibitors with an isoxazol-5(2H)-one scaffold. The most potent compound (2o) had a good balance between HNE inhibitory activity (IC50 value =20 nM) and chemical stability in aqueous buffer (t1/2=8.9 h). Analysis of reaction kinetics revealed that the most potent isoxazolone derivatives were reversible competitive inhibitors of HNE. Furthermore, since compounds 2o and 2s contain two carbonyl groups (2-N-CO and 5-CO) as possible points of attack for Ser195, the amino acid of the active site responsible for the nucleophilic attack, docking studies allowed us to clarify the different roles played by these groups.

Keywords: Isoxazol-5(2H)-one, human neutrophil elastase, HNE inhibitor, chemical stability, molecular docking

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Human neutrophil elastase (HNE) is a member of the chymotrypsin superfamily of serine proteases and is primarily expressed in neutrophil azurophilic granules1,2. It is one of the few proteases able to degrade the matrix protein elastin, but can also degrade a variety of extracellular other matrix proteins, such as fibronectin, collagen, proteoglycans, and laminin3. Moreover, HNE plays a pivotal role both in intracellular and extracellular innate immune responses against bacteria4. HNE performs its proteolytic action on the membranes of Gram-negative bacteria engulfed in neutrophil phagolysosomes5 and in association with special structures called “neutrophil extracellular traps” (NETs) that are extruded into the extracellular space6. High molecular weight serine protease inhibitors called SERPINs (e.g. alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT), elafin, and secretory leucocyte protease inhibitor) strictly regulate HNE activity to prevent uncontrolled proteolysis, and alteration of the protease–antiprotease balance7,8 plays an important role in some inflammatory diseases, mainly those involving the respiratory system. For example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)9 is characterised by an impaired protease–antiprotease balance. Likewise, cystic fibrosis (CF)10, bronchiectasis (BE), pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), acute lung injury (ALI), and adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)11,12 involve imbalances in protease–antiprotease activities. HNE has also recently been implicated in the progression of various types of cancer and other important neutrophil-driven inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease13.

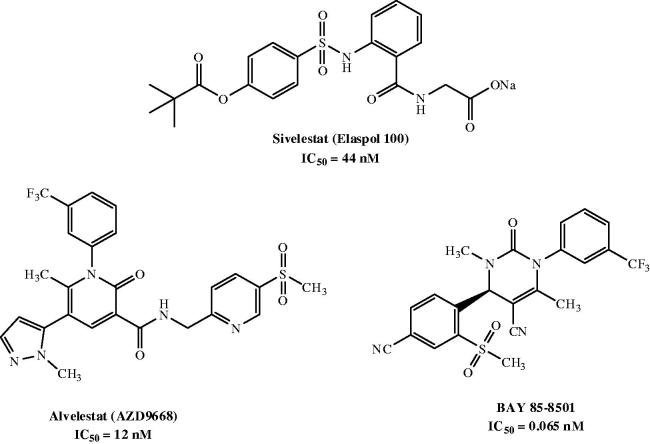

In the last three decades, research on the development of innovative elastase inhibitors has resulted in the synthesis of a number of new compounds, including peptide and non-peptide derivatives14,15. Currently, Sivelestat (Elaspol® 100) is the only non-peptide drug available for the treatment of ALI/ARDS16, although it is only marketed in Japan and Korea. Sivelestat has been also used in paediatric heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), where it attenuated the perioperative inflammatory response due to release of neutrophil proteolytic enzymes such as elastase17. Additionally, two potent and orally active candidates, AZD9668 (Alvelestat, Astra Zeneca, Cambridge, UK)18,19 and BAY 85-8501 (Bayer HealthCare, Leverkusen, Germany)20, are in clinical trials (Phase II) for patients with BE, CF, COPD, and pulmonary disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HNE inhibitors.

Our interest in the design and synthesis of new non-peptide HNE inhibitors resulted from the discovery of a potent class of HNE inhibitors with a N-benzoylindazole scaffold21,22. These compounds had IC50 values in the low nanomolar range. Studies on their mechanism of action demonstrated that these compounds were competitive and pseudo-irreversible HNE inhibitors with greater selectivity for HNE versus other serine proteases and had appreciable chemical stability in aqueous buffer. Further work led to additional interesting HNE inhibitors with cinnoline23 and indole24 scaffolds.

In the present study, we report a novel class of HNE inhibitors with an isoxazol-5(2H)-one core. We designed and synthesised small and flexible molecules bearing alkyl groups at positions 3 and 4 or 4-unsubstituted derivatives, also introducing those substituents identified in our previous compound series21–23 to be fundamental for HNE inhibitory activity.

Materials and methods

All melting points were determined on a Büchi apparatus (New Castle, DE) and are uncorrected. Extracts were dried over Na2SO4, and the solvents were removed under reduced pressure. Merck F-254 commercial plates (Merck, Durham, NC) were used for analytical TLC to follow the course of the reactions. Silica gel 60 (Merck 70–230 mesh, Merck, Durham, NC) was used for column chromatography. 1H NMR, 13C NMR, HSQC, and HMBC spectra were recorded on an Avance 400 instrument (Bruker Biospin Version 002 with SGU, Bruker Inc., Billerica, MA). Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm to the nearest 0.01 ppm using the solvent as an internal standard. Coupling constants (J values) are presented in Hz as calculated using TopSpin 1.3 software (Nicolet Instrument Corp., Madison, WI) and are rounded to the nearest 0.1 vHz. Mass spectra (m/z) were recorded on an ESI-TOF mass spectrometer (Brucker Micro TOF, Bruker Inc., Billerica, MA), and reported mass values are within the error limits of ±5 ppm mass units. Microanalyses indicated by the symbols of the elements or functions were performed with a Perkin–Elmer 260 elemental analyser (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA) for C, H, and N, and the results were within ±0.4% of the theoretical values, unless otherwise stated. Reagents and starting material were commercially available. The purity of all tested compounds is >95%. The crystal structure of compound 2j was solved by single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

Chemistry. General procedure for synthesis of compounds (2a–s). To a suspension of the appropriate substrates 1a–f25–29 (0.86 mmol) in 10 ml of anhydrous THF, 1.72 mmol of sodium hydride and 1.03 mmol of the appropriate acyl/aroyl chloride were added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The solvent was concentrated in vacuo to obtain the final compounds 2a–s, which were purified by column chromatography using cyclohexane/ethyl acetate (2:1 for 2a,i,s; 3:1 for 2e,g,h,j,k,p,q; 4:1 for 2c,l,m; and 5:1 for 2d,r] or toluene/ethyl acetate 9.5:0.5 (2b,f,n,o) as eluents.

2-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)-3,4-dimethylisoxazol-5(2H)-one (2a). Yield = 32%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.02–1.07 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.12–1.17 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.82 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.34–2.40 (m, 1H, CH cC3H5), 2.49 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 6.26 (CH3), 10.44 (CH2), 12.50 (CH), 13.77 (CH3), 102.41 (C), 153.33 (C), 167.77 (C), 168.74 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C9H11NO3, 181.19; found: m/z 182.08 [M + H]+. Anal. C9H11NO3 (C, H, N).

3,4-Dimethyl-2-(3-methylbenzoyl)isoxazol-5(2H)-one (2b). Yield = 30%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.75 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.05 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.41 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 7.35 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.44 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.80–7.85 (m, 2H, Ar). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 10.99 (CH3), 20.12 (CH3), 21.23 (CH3), 29.70 (C), 127.38 (CH), 128.65 (CH), 130.68 (CH), 135.28 (CH), 134.10 (C), 138.70 (C), 143.10 (C), 157.61 (C), 169.57 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C13H13NO3, 231.25; found: m/z 232.09 [M + H]+. Anal. C13H13NO3 (C, H, N).

2-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)-4-ethyl-3-methylisoxazol-5(2H)-one (2c). Yield = 26%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 0.98–1.05 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.10 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.6 Hz), 1.13–1.18 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 2.26 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.6 Hz), 2.34–2.40 (m, 1H, CH cC3H5), 2.50 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 10.96 (CH2), 13.09 (CH3), 13.58 (CH3), 14.06 (CH), 15.53 (CH2), 108.58 (C), 153.56 (C), 167.87 (C), 169.34 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C10H13NO3, 195.22; found: m/z 196.09 [M + H]+. Anal. C10H13NO3 (C, H, N).

4-Ethyl-3-methyl-2-(3-methylbenzoyl)isoxazol-5(2H)-one (2d). Yield = 34%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.13 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.6 Hz), 2.31 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.6 Hz), 2.39 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.61 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 7.30–7.37 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.61–7.66 (m, 2H, Ar). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 12.99 (CH3), 13.90 (CH2), 15.13 (CH3), 21.34 (CH3), 109.02 (C), 126.61 (CH), 127.70 (CH), 129.75 (CH), 131.41 (C), 133.78 (CH), 138.18 (C), 154.31 (C), 163.72 (C), 167.41 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H15NO3, 245.27; found: m/z 246.11 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H15NO3 (C, H, N).

2-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)-3-ethyl-4-methylisoxazol-5(2H)-one (2e). Yield = 54%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 0.97–1.05 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.13–1.18 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.20 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.82 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.34–2.40 (m, 1H, CH cC3H5), 2.90 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 6.03 (CH), 10.37 (CH2), 12.06 (CH3), 12.66 (CH3), 20.74 (CH2), 102.22 (C), 158.53 (C), 167.89 (C), 168.23 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C10H13NO3, 195.22; found: m/z 196.09 [M + H]+. Anal. C10H13NO3 (C, H, N).

3-Ethyl-4-methyl-2-(3-methylbenzoyl)isoxazol-5(2H)-one (2f). Yield = 10%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.30 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.6 Hz), 1.85 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.44 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 2.64 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.41 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.49 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.96 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 5.92 (CH3), 11.36 (CH3), 19.55 (CH2), 21.41 (CH3), 97.56 (C), 127.03 (C), 127.96 (CH), 128.76 (CH), 131.21 (CH), 135.47 (CH), 138.45 (C), 161.76 (C), 161.96 (C), 167.00 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H15NO3, 245.27; found: m/z 246.11 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H15NO3 (C, H, N).

Ethyl 2-(cyclopropanecarbonyl)-4-methyl-5-oxo-2,5-dihydroisoxazole-3-carboxylate (2g). Yield = 38%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.11–1.16 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.17–1.23 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.35 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.95 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.25–2.31 (m, 1H, CH cC3H5), 4.41 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 6.89 (CH), 10.91 (CH2), 12.40 (CH3), 13.88 (CH3), 63.22 (CH2), 107.85 (C), 145.28 (C), 158.92 (C), 167.45 (C), 168.67 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C11H13NO5, 239.22; found: m/z 240.08 [M + H]+. Anal. C11H13NO5 (C, H, N).

Ethyl 4-methyl-2-(3-methylbenzoyl)-5-oxo-2,5-dihydroisoxazole-3-carboxylate (2h). Yield = 21%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.42 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.08 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.44 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 4.45 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.42 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.51 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.97 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 6.68 (CH3), 14.16 (CH3), 21.26 (CH3), 62.03 (CH2), 101.14 (C), 126.42 (C), 128.07 (CH), 128.90 (CH), 131.34 (CH), 135.89 (CH), 138.81 (C), 156.61 (C), 160.17 (C), 161.66 (C), 163.86 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C15H15NO5, 289.28; found: m/z 290.10 [M + H]+. Anal. C15H15NO5 (C, H, N).

2-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)-3-ethylisoxazol-5(2H)-one (2i). Yield = 47%; mp =92–95 °C (EtOH). 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.05–1.10 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.14–1.19 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.25 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.36–2.42 (m, 1H, CH cC3H5), 2.95 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.4 Hz), 5.32 (s, 1H, CH). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 10.83 (CH2), 11.33 (CH3), 12.69 (CH), 22.69 (CH2), 92.92 (CH), 164.65 (C), 166.69 (C), 168.69 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C9H11NO3, 181.19; found: m/z 182.08 [M + H]+. Anal. C9H11NO3 (C, H, N).

3-Ethyl-2-(3-methylbenzoyl)isoxazol-5(2H)-one (2j). Yield = 48%; mp =81–84 °C (EtOH). 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.32 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.40 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 3.09 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.4 Hz), 5.41 (s, 1H, CH), 7.33–7.40 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.64–7.69 (m, 2H, Ar). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 11.49 (CH3), 21.36 (CH3), 23.07 (CH2), 93.81 (CH), 127.02 (CH), 128.28 (CH), 130.23 (CH), 131.04 (C), 134.05 (CH), 138.28 (C), 163.38 (C), 166.20 (C), 166.66 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C13H13NO3, 231.25; found: m/z 232.09 [M + H]+. Anal. C13H13NO3 (C, H, N).

3-Isopropyl-2-propionylisoxazol-5(2H)-one (2k). Yield = 47%; mp = 92–95 °C (EtOH). 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.15 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.4 Hz), 1.23 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.72 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.4 Hz), 3.50–3.57 (m, 1H, CH(CH3)2), 5.27 (s, 1H, CH). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 7.73 (CH3), 21.08 (CH3), 28.10 (CH), 28.54 (CH2), 91.70 (CH), 166.50 (C), 168.45 (C), 169.51 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C9H13NO3, 183.20; found: m/z 184.09 [M + H]+. Anal. C9H13NO3 (C, H, N).

2-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)-3-isopropylisoxazol-5(2H)-one (2l). Yield = 27%; mp = 55–57 °C (EtOH). 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.07–1.12 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.16–1.21 (m, 2H, CH2 cC3H5), 1.26 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.38–2.45 (m, 1H, CH cC3H5), 3.54–3.61 (m 1H, CH(CH3)2), 5.33 (s, 1H, CH). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 10.88 (CH2), 12.94 (CH), 21.17 (CH3), 28.18 (CH), 91.72 (CH), 166.50 (C), 168.45 (C), 169.51 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C10H13NO3, 195.22; found: m/z 196.09 [M + H]+. Anal. C10H13NO3 (C, H, N).

2-(Cyclopentanecarbonyl)-3-isopropylisoxazol-5(2H)-one (2m). Yield = 23%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.26 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.63–1.74 (m, 4H, 2 × CH2 cC5H9), 1.82–1.87 (m, 2H, CH2 cC5H9), 1.97–2.02 (m, 2H, CH2 cC5H9), 3.32–3.37 (m, 1H, CH cC5H9), 3.57–3.62 (m, 1H, CH(CH3)2), 5.30 (s, 1H, CH). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 21.12 (CH3), 25.95 (CH2), 28.17 (CH), 29.56 (CH2), 43.61 (CH), 91.66 (CH), 166.68 (C), 169.74 (C), 170.93 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C12H17NO3, 223.27; found: m/z 224.12 [M + H]+. Anal. C12H17NO3 (C, H, N).

3-Isopropyl-2-(3-methylbenzoyl)isoxazol-5(2H)-one (2n). Yield = 17%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.34 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.41 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 3.70–3.78 (m 1H, CH(CH3)2), 5.42 (s, 1H, CH), 7.33–7.41 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.62–7.67 (m, 2H, Ar). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 21.44 (CH3), 28.50 (CH), 92.85 (CH), 127.15 (CH), 128.30 (CH), 130.23 (CH), 131.38 (C), 134.08 (CH), 138.32 (C), 163.56 (C), 166.83 (C), 171.07 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H15NO3, 245.27; found: m/z 246.11 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H15NO3 (C, H, N).

3-Isopropyl-2-(4-methylbenzoyl)isoxazol-5(2H)-one (2o). Yield = 45%; mp =77–79 °C (EtOH). 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.33 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 7.0 Hz), 2.41 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 3.66–3.79 (m 1H, CH(CH3)2), 5.40 (s, 1H, CH), 7.26 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.78 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 21.91 (CH3), 22.30 (CH3), 29.05 (CH), 93.10 (CH), 129.04 (C), 129.66 (CH), 130.69 (CH), 144.82 (C), 163.72 (C), 167.36 (C), 171.67 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H15NO3, 245.27; found: m/z 246.11 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H15NO3 (C, H, N).

3-(3-Isopropyl-5-oxo-2,5-dihydroisoxazole-2-carbonyl)benzonitrile (2p). Yield = 14%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.31 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.00–3.09 (m, 1H, CH(CH3)2), 6.09 (s, 1H, CH), 7.70 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.96 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.41 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.46 (s, 1H, Ar). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 21.92 (CH3), 28.09 (CH), 86.78 (CH), 114.41 (C), 117.84 (C), 129.29 (C), 130.69 (CH), 134.65 (CH), 134.98 (CH), 138. 19 (CH), 159.16 (C), 164.82 (C), 172.17 (C). IR = 1600 cm−1 (C=O amide), 1777 cm−1 (C=O ester), 2235 cm−1 (CN). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H12N2O3, 256.26; found: m/z 257.09 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H12N2O3 (C, H, N).

4-(3-Isopropyl-5-oxo-2,5-dihydroisoxazole-2-carbonyl)benzonitrile (2q). Yield = 38%; mp = 113–115 °C (EtOH). 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.30 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.00–3.09 (m 1H, CH(CH3)2), 6.10 (s, 1H, CH), 7.84 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 8.29 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 21.29 (CH3), 27.48 (CH), 86.16 (CH), 117.46 (C), 118.11 (C), 131.03 (CH), 132.72 (CH), 158.88 (C), 164.28 (C), 171.60 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H12N2O3, 256.26; found: m/z 257.09 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H12N2O3 (C, H, N).

3-Isopropyl-2-(3-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl)isoxazol-5(2H)-one (2r). Yield = 21%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.39 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.73–3.78 (m, 1H, CH(CH3)2), 5.51 (s, 1H, CH), 7.66 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.87 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.09 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.14 (s, 1H, Ar). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 21.83 (CH3), 29.12 (CH), 94.07 (CH), 127.33 (C), 129.64 (CH), 130.20 (C), 131.93 (C), 132.87 (CH), 133.45 (CH), 162.29 (C), 166.72 (C), 171.54 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H12F3NO3, 299.25; found: m/z 300.08 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H12F3NO3 (C, H, N).

3-Isopropyl-2-(4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl)isoxazol-5(2H)-one (2s). Yield = 16%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.36 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.69–3.77 (m 1H, CH(CH3)2), 5.47 (s, 1H, CH), 7.75 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.97 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 21.24 (CH3), 28.51 (CH), 93.46 (CH), 125.40 (CH), 127.30 (C), 130.09 (CH), 130.20 (C), 134.72 (C), 161.81 (C), 166.10 (C), 170.86 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H12F3NO3, 299.25; found: m/z 300.08 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H12F3NO3 (C, H, N).

General procedure for synthesis of compounds (3a,b). To a suspension of the appropriate substrate 2l or 2n (0.36 mmol) in 5 ml of anhydrous toluene, 0.72 mmol of Lawesson’s reagent were added. The mixture was stirred at reflux for 6 h, cooled, concentrated in vacuo, diluted with ice-cold water (10 ml), and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 ml). The organic phase was dried over sodium sulphate, and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo to obtain the final compounds 3a,b, which were purified by column chromatography using cyclohexane/ethyl acetate as eluent (ratio: 5:1 for 3a and 3:1 for 3b).

Cyclopropyl-(3-isopropyl-5-thioxoisoxazol-2(5H)-yl)methanone (3a). Yield = 26%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.17–1.24 (m, 4H, 2 × CH2 cC3H5), 1.27 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.55–2.61 (m, 1H, CH cC3H5), 3.54–3.61 (m, 1H, CH(CH3)2), 6.12 (s, 1H, CH). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 10.88 (CH2), 14.76 (CH), 21.15 (CH3), 35.40 (CH), 106.37 (CH), 166.84 (C), 169.52 (C), 171.69 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C10H13NO2S, 211.28; found: m/z 212.07 [M + H]+. Anal. C10H13NO2S (C, H, N).

(3-Isopropyl-5-thioxoisoxazol-2(5H)-yl)-(m-tolyl)methanone (3b). Yield = 40%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.32 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 6.4 Hz), 2.44 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 2.83–2.92 (m, 1H, CH(CH3)2), 7.05 (s, 1H, CH), 7.36–7.41 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.81–7.86 (m, 2H, Ar). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 21.09 (CH3), 37.59 (CH3), 108.44 (CH), 122.51 (CH), 124.40 (CH), 127.37 (CH), 129.54 (CH), 131.38 (C), 134.14 (CH), 138.32 (C), 163.56 (C), 169.76 (C), 175.11 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H15NO2S, 261.34; found: m/z 262.09 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H15NO2S (C, H, N).

General procedure for synthesis of compounds (4a,b). A mixture of the appropriate intermediates (1a25 or 1f29) (0.63 mmol), K2CO3 (1.26 mmol), and 1-(chloromethyl)-3-methylbenzene (0.95 mmol) in 2 ml of anhydrous acetonitrile was stirred at reflux for 2 h. After cooling, the mixture was concentrated in vacuo, diluted with ice-cold water (10 ml), and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 ml). The organic phase was dried over sodium sulphate, and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo to obtain the final compounds 4a,b, which were purified by column chromatography using cyclohexane/ethyl acetate as eluent (ratio: 1:1 for 4a and 2:1 for 4b).

3,4-Dimethyl-2-(3-methylbenzyl)isoxazol-5(2H)-one (4a). Yield = 26%; mp = 80–83 °C (EtOH). 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.73 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.13 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.32 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 4.59 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.03–7.12 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.20 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 6.75 (CH3), 11.30 (CH3), 29.70 (CH3), 55.18 (CH2), 100.16 (C), 125.42 (CH), 128.63 (CH), 129.10 (CH), 129.19 (CH), 133.40 (C), 138.50 (C), 160.32 (C), 171.85 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C13H15NO2, 217.26; found: m/z 218.11 [M + H]+. Anal. C13H15NO2 (C, H, N).

3-Isopropyl-2-(3-methylbenzyl)isoxazol-5(2H)-one (4b). Yield = 14%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.24 (d, 6H, CH(CH3)2, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.33 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 2.73–2.79 (m, 1H, CH(CH3)2), 4.74 (s, 2H, CH2), 5.00 (s, 1H, CH), 7.02–7.07 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.12 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.22 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.4 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 21.41 (CH3), 21.60 (CH3), 26.58 (CH), 56.00 (CH2), 81.50 (CH), 124.93 (CH), 129.40 (CH), 133.87 (CH), 138.22 (C), 138.81 (CH), 141.50 (C), 171.51 (C), 174.09 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H17NO2, 231.29; found: m/z 232.13 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H17NO2 (C, H, N).

Procedure for synthesis of ethyl 4-methyl-5-oxo-2-(m-tolyl)-2,5-dihydroisoxazole-3-carboxylate (4c). A mixture of dry CH2Cl2 (8 ml), 1d28 (0.58 mmol), 3-methylphenylboronic acid (1.16 mmol), Cu(Ac)2 (0.87 mmol), and Et3N (0.87 mmol) was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 20 ml), then with 33% aqueous ammonia (3 × 5 ml). The organic phase was dried over sodium sulphate, and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo to obtain the final compound 4c, which was purified by column chromatography using cyclohexane/ethyl acetate 3:1 as eluent. Yield = 59%; oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 1.16 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.16 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.36 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 4.23 (q, 2H, CH2CH3,J = 7.2 Hz), 7.03–7.08 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.20 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.28 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3-d1) δ 8.38 (CH3), 14.06 (CH3), 21.36 (CH3), 62.47 (CH2), 111.35 (C), 122.73 (CH), 126.24 (CH), 129.03 (CH), 130.60 (CH), 139.48 (C), 140.23 (C), 150.44 (C), 158.63 (C), 171.24 (C). ESI-MS calcd. for C14H15NO4, 261.27; found: m/z 262.10 [M + H]+. Anal. C14H15NO4 (C, H, N).

HNE inhibition assay. Compounds were dissolved in 100% DMSO at 5 mM stock concentrations. The final concentration of DMSO in the reactions was 1%, and this level of DMSO had no effect on enzyme activity. The HNE inhibition assay was performed in black flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates. Briefly, a buffer solution containing 200 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 0.01% bovine serum albumin, 0.05% Tween-20, and 20 mU/ml of HNE (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) was added to wells containing different concentrations of each compound. The reaction was initiated by addition of 25 μM elastase substrate (N-methylsuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin, Calbiochem) in a final reaction volume of 100 μL/well. Kinetic measurements were obtained every 30 s for 10 min at 25 °C using a Fluoroskan Ascent FL fluorescence microplate reader (Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA) with excitation and emission wavelengths at 355 and 460 nm, respectively. For all compounds tested, the concentration of inhibitor that caused 50% inhibition of the enzymatic reaction (IC50) was calculated by plotting % inhibition versus logarithm of inhibitor concentration (at least six points). The data are presented as the mean values of at least three independent experiments with relative standard deviations of <15%.

Analysis for compound stability

Spontaneous hydrolysis of selected derivatives was evaluated at 25 °C in 0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.3. Kinetics of hydrolysis were monitored by measuring changes in absorbance spectra over time using a SpectraMax Plus microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Absorbance (At) at the characteristic absorption maxima of each compound was measured at the indicated times until no further absorbance decreases occurred (A∞)30. Using these measurements, we created semilogarithmic plots of log(At – A∞) versus time, and k′ values were determined from the slopes of these plots. Half-conversion times were calculated using t1/2=0.693/k′, as described previously21.

Molecular modelling

Initial structures of the compounds were generated with HyperChem 8.0 (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) and optimised by the semi-empirical PM3 method. Docking of the molecules was performed using Molegro Virtual Docker (CLC Bio, København, Denmark) (MVD), version 4.2.0 (CLC Bio, København, Denmark), as described previously22. The structure of HNE complexed with a peptide chloromethyl ketone inhibitor31 was used for the docking study (1HNE entry of the Protein Data Bank). The search area for docking poses was defined as a sphere with a 10 Å radius centred at the nitrogen atom in the five-membered ring of the peptide chloromethyl ketone inhibitor. After removal of this peptide and co-crystallised water molecules from the program workspace, we set side chain flexibility for the 42 residues closest to the centre of the search area22. Fifteen docking runs were performed for each compound, with full flexibility of a ligand around all rotatable bonds and side chain flexibility of the above-mentioned residues of the enzyme. Parameters used within Docking Wizard of the Molegro program were as described previously22. The docking poses corresponding to the lowest-energy binding mode of each inhibitor were evaluated for the ability to form a Michaelis complex between the hydroxyl group of Ser195 and the carbonyl group in the amido moiety of an inhibitor. For this purpose, values of d1 [distance O(Ser195)·C between the Ser195 hydroxyl oxygen atom and the inhibitor carbonyl carbon atom closest to O(Ser195)] and α [angle O(Ser195)···C=O, where C=O is the carbonyl group of an inhibitor closest to O(Ser195)] were determined for each docked compound32. In addition, we estimated the possibility of proton transfer from Ser195 to Asp102 through His57 (the key catalytic triad of serine proteases) by calculating distances d2 between the NH hydrogen in His57 and carboxyl oxygen atoms in Asp102, as described previously22. The distance between the hydroxyl proton in Ser195 and the pyridine-type nitrogen in His57 is also important for proton transfer. However, because of easy rotation of the hydroxyl about the C–O bond in Ser195, we measured distance d3 between the oxygen in Ser195 and the basic nitrogen atom in His57. The effective length L of the channel for proton transfer was calculated as L=d3+min (d2).

Crystallographic analysis

The data were collected at 100(2) K on Xcalibur3 CCD 4-circle diffractometer using a graphite monochromator, Mo Ka radiation. A reference frame was monitored every 50 frames to control the stability of the crystal, and the system revealed no intensity decay. The data set was corrected for Lorentz, polarisation effects, and absorption corrections were performed by the ABSPACK33 multi-scan procedure of the CrysAlis data reduction package. The structure was solved using the direct method with SUPERFLIP34 software, and the refinement was carried out using the SHELXL-201335 software package. All non-hydrogen atoms were located from the initial solution or from subsequent electron density difference maps during the initial course of the refinement. After locating the non-hydrogen atoms, the models were refined against F2, first using isotropic and finally anisotropic thermal displacement parameters. Hydrogen atoms have been introduced as “riding hydrogens”. Programs used in the crystallographic calculations included WinGX436 and Mercury37 for graphics. Crystal structural data are available from the Cambridge Crystallographic CCDC 1036557.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

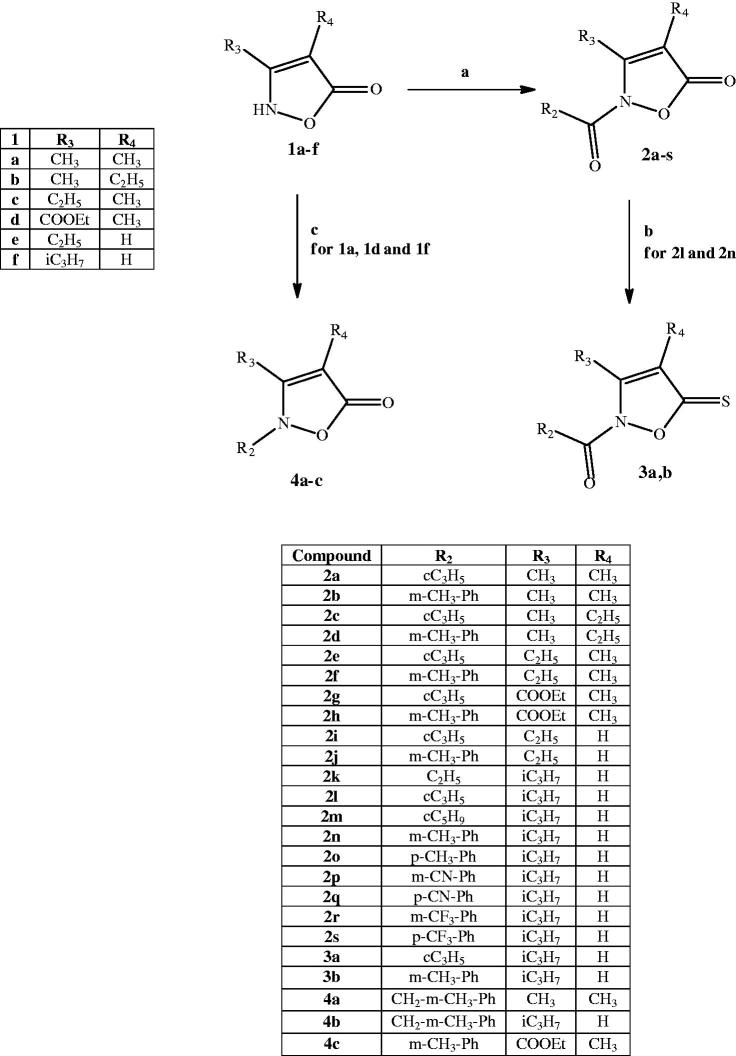

The synthetic pathways leading to compounds 2a–s, 3a,b, and 4a–c are shown in Scheme 1. Compounds of type 2 were obtained by treatment of the isoxazolones 1a–f25–29 with the appropriate acyl/aroyl chloride and sodium hydride in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran. Compounds 2l and 2n were further converted into the corresponding thioxoisoxazolones 3a,b with Lawesson’s reagent. Alkylation of 1a and 1f with 3-methylbenzyl chloride in anhydrous acetonitrile and K2CO3 and of 1d with 3-methylphenyl boronic acid, copper acetate, and triethylamine in anhydrous dichloromethane by a coupling reaction resulted in 4a,b and 4c, respectively. All of the final compounds were identified by 1H NMR and 13C NMR. Moreover, heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) and heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) two-dimensional NMR analyses were performed for representative products. Finally, since the literature describes the presence of tautomer's of the isozazol-5(2H)-one nucleus38–40, a crystallographic analysis of 2j (Figure 2) was performed in order to univocally assign the structure (see Supplemental data).

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) R2-COCl, NaH, anhydrous THF, r.t., 24 h; (b) Lawesson’s reagent, toluene, reflux, 5 h; (c) for 4a,b: 3-methylbenzyl chloride, K2CO3, anhydrous CH3CN, 80 °C, 2 h; for 4c: 3-methylphenyl boronic acid, (CH3COO)2Cu, Et3N, anhydrous CH2Cl2, r.t., 24 h.

Figure 2.

X-ray structure of compound 2j.

Biological evaluation and structure–activity relationship (SAR) analysis

All compounds were evaluated for their ability to inhibit HNE in comparison with Sivelestat, a reference HNE inhibitor, and the results presented in Table 1 demonstrated that the isoxazolone nucleus is an appropriate scaffold for HNE inhibitor development. These compounds display two carbonyl groups (2-N-CO and 5-CO) as possible points of attack for Ser195, the amino acid of the HNE active site responsible for the nucleophilic attack. The observation that all 2-N-acyl/aroyl derivatives were active HNE inhibitors (2a–s), while the 2-N-alkyl/aryl derivatives were completely inactive (4a–c), seems to suggest that the carbonyl group involved in the catalysis is the amidic carbonyl at position 2. Indeed, this observation is consistent with our previous results for indazole derivatives21,22.

Table 1.

HNE inhibitory activity of isoxazolone derivatives 2a–s, 3a,b, 4a–c.

| ||||

| Compound |

R2 |

R3 |

R4 |

IC50 (μM)a |

| 2a | cC3H5 | CH3 | CH3 | 0.12 ± 0.023 |

| 2b | m-CH3-Ph | CH3 | CH3 | 10.9 ± 1.2 |

| 2c | cC3H5 | CH3 | C2H5 | 0.13 ± 0.025 |

| 2d | m-CH3-Ph | CH3 | C2H5 | 0.094 ± 0.023 |

| 2e | cC3H5 | C2H5 | CH3 | 2.2 ± 0.28 |

| 2f | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | CH3 | 1.8 ± 0.32 |

| 2g | cC3H5 | COOEt | CH3 | 0.44 ± 0.14 |

| 2h | m-CH3-Ph | COOEt | CH3 | 39.7 ± 5.1 |

| 2i | cC3H5 | C2H5 | H | 0.096 ± 0.022 |

| 2j | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | H | 0.043 ± 0.011 |

| 2k | C2H5 | iC3H7 | H | 1.1 ± 0.14 |

| 2l | cC3H5 | iC3H7 | H | 0.034 ± 0.009 |

| 2m | cC5H9 | iC3H7 | H | 0.56 ± 0.15 |

| 2n | m-CH3-Ph | iC3H7 | H | 0.042 ± 0.011 |

| 2o | p-CH3-Ph | iC3H7 | H | 0.020 ± 0.007 |

| 2p | m-CN-Ph | iC3H7 | H | 6.5 ± 1.7 |

| 2q | p-CN-Ph | iC3H7 | H | 18.2 ± 2.5 |

| 2r | m-CF3-Ph | iC3H7 | H | 1.2 ± 0.22 |

| 2s | p-CF3-Ph | iC3H7 | H | 0.034 ± 0.012 |

| 3a | cC3H5 | – | – | 2.1 ± 0.31 |

| 3b | m-CH3-Ph | – | – | NAb |

| 4a | CH2-m-CH3-Ph | CH3 | CH3 | NAb |

| 4b | CH2-m-CH3-Ph | iC3H7 | H | NAb |

| 4c | m-CH3-Ph | COOEt | CH3 | NAb |

| Sivelestat | – | – | – | 0.050 ± 0.020 |

IC50 values are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

NA: no inhibitory activity was found at the highest concentration of compound tested (50 μM).

The presence of small alkyl groups at positions 3 and 4 (2a–f) led to compounds with HNE inhibitory activity in the micromolar/submicromolar range, whereas the introduction at position 3 of a carbethoxy group (2g,h) gave different results, depending on the substituent at N-2. The elimination of methyl group at position 4 (2i–2s) resulted in compounds endowed with excellent inhibitory activity, indicating the importance of the unsubstitution of this position. This fact can be highlighted by compounds 2i and 2j which show 22- and 42-fold higher inhibitory activity (IC50=96 and 43 nM, respectively) with respect to the corresponding 4-methyl derivatives 2e and 2f (IC50=2.2 and 1.8 μM, respectively). On the other hand, in the 4-unsubstituted series, compounds 2l, 2n, 2o, and 2s also exhibited IC50 values in the nanomolar range (20–42 nM). Moreover, substitution of the methyl at 2-benzoyl group in the potent compounds 2n and 2o with a trifluoromethyl group (2r and 2s) did not affect inhibitory activity when the substituent was in the para position of the benzoyl group (i.e. compounds 2o and 2s with IC50=20 and 34 nM, respectively) but resulted in loss of activity when the substituent was in the meta position.

To evaluate the importance of the 5-CO group, which does not seem to be involved in catalysis, we synthesised 3a and 3b as thio analogues of the two potent compounds 2l and 2n. However, the low activity (3a, IC50=2.1 μM) or inactivity (3b) of these new products clearly suggests that the 5-CO group is important for interaction with the target. To assess if this inactivity was the result of increased bulkiness and/or a weaker H-binding acceptor effect of sulphur versus oxygen in the carbonyl or if it was related to other reasons, we performed molecular modelling studies.

Molecular modelling

To further investigate the interaction of these new compounds with HNE, molecular docking of isoxazolones derivatives 2l, 2n, 2o, 2q, 3a, and 3b into the HNE binding site (1HNE entry of Protein Data Bank) was performed. Side chains of selected residues in the HNE binding site were considered flexible, as described in our previous modelling studies22,24. According to the docking scores ΔE of the poses (Table 2), isoxazolones are effectively anchored within HNE binding site. However, it is well-known that catalytic activity of serine proteases is related to synchronous proton transfer from serine via histidine to aspartate residues41. In HNE, this catalytic triad corresponds to Ser195, His57, and Asp102, respectively. The length of the proton transfer channel is characterised by the magnitude of L (see Table 2). Additionally, effectiveness of HNE binding to a ligand depends on its ability to form a Michaelis complex between a carbonyl group of the ligand and an oxyanion hole centred at the hydroxyl oxygen atom of Ser195. Geometry which favours Michaelis complex formation corresponds to ligand orientation with angle α values from 80° to 120° and with shortened distance d1 (1.8–2.6 Å)41 (Table 2). Although a low-energy docking pose of each ligand is not completely identical to the Michaelis complex, they must have certain similarity. Hence, it is reasonable to use the geometry of the low-energy pose to evaluate possibility of complex formation.

Table 2.

Biological activities, geometric parameters, and docking scores of the enzyme–inhibitor complexes predicted by molecular docking with MVD.

| Comp. | IC50 (μM)a | α | d1 | d2 | d3 | Lb | Docking score ΔE (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2lc | 0.034 | 85.2 | 2.903 | 2.763, 3.967 | 2.829 | 5.592 | –58.9 |

| 3a | 2.1 | 139.6 | 4.148 | 2.379, 3.611 | 2.560 | 4.939 | –44.0 |

| 2n | 0.042 | 81.6 | 3.861 | 2.399, 3.627 | 2.596 | 4.995 | –34.2 |

| 3b | NA | 148.3 | 4.659 | 2.750, 3.962 | 2.849 | 5.599 | –21.1 |

| 2oc | 0.020 | 104.1 | 3.134 | 2.760, 3.975 | 2.819 | 5.579 | –67.6 |

| 2qc | 18.2 | 89.4 | 4.500 | 3.130, 4.319 | 3.286 | 6.416 | –58.4 |

HNE inhibitory activity.

The length of the proton transfer channel was calculated as L=d3+min(d2).

According to the docking results, a Michaelis complex with Ser195 is formed with participation of the ester carbonyl group.

Compounds 2l, 2n, 2o, 2q, 3a, and 3b occupy an area in the HNE binding site in the vicinity of the terminal part of the co-crystallised peptide. As presented in Table 2, the sulphur-containing compounds 3a and 3b had larger distances d1 (4.148 Å and 4.659 Å, respectively) than their counterparts 2l and 2n and were characterised by an angle α that was not suitable for easy formation of a Michaelis complex (139.6° and 148.3°, respectively). The different orientation within the binding site of sulphur compounds, with respect to compounds containing the 5-carbonyl group could also be caused by higher values of C=S bond length and radius of the sulphur atom (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Docking poses of compounds 2n (lower compound) and 3b (upper compound). The ovals represent the C=S and C=O fragment of the two compounds, respectively. Residues within 6 Å from the co-crystallized ligand are shown.

From the docking studies, it is interesting to note that these isoxazolone compounds show involvement of the endocyclic carbonyl group in formation of a Michaelis adduct, but also the amide carbonyl group is important for proper anchoring of the ligands to the enzyme pocket. For example, compounds 2o and 2q show values of angle α in the exact range (Table 2) and are located similarly in the HNE binding site to allow formation a Michaelis complex with the endocyclic carbonyl group. In particular, inhibitor 2o, which has the best inhibitory activity (IC50=20 nM) forms a hydrogen bond between the oxygen of the 5-carbonyl group and the NH group of Ser195 (Figure 4) that likely improves the enzyme-ligand orientation, in addition to the involvement of the 5-carbonyl carbon atom and the Ser195 hydroxyl group, for the formation of the Michaelis complex.

Figure 4.

Docking pose of compound 2o. Residues within 3 Å of the pose are visible. The H-bond is shown by a dashed line and is indicated by the arrow.

In compound 2q, the 5-carbonyl group (carbon atom) is located at a longer distance d1 from Ser195 than that of 2o (see Table 2). This is due to the H-bond interaction of the oxygen atom of the 5-carbonyl group that involves the NH group of Gly193 instead of the NH group of Ser195. Moreover, for derivative 2q, the imidazole ring of His57 is rotated unfavourably, thus enhancing the length L of the proton transfer channel (Table 2). Consequently, the conditions for formation of a Michaelis complex are not as suitable and lead to reduced inhibitory activity (IC50=18.2 μM). Differences between 2o and 2q, which are p-tolyl- and p-cyanophenyl derivatives, respectively, could also likely be related to variations in hydrophobicity, polarity of substituents, and different orientation of flexible side chains in the ligand–enzyme complex. Thus, our docking studies indicate that the 2-amido carbonyl group also plays an important role in positioning the ligand within the binding site, although the attack of the Ser195 is directed at the endocyclic C=O group (5-carbonyl group).

The sum of non-bonding interaction energies between HNE and the two atoms of the amido carbonyl moiety of 2o equals –12.86 kcal/mol, which is even more negative than for the endocyclic carbonyl (–9.11 kcal/mol), indicating a strong interaction with the enzyme. Non-specific Van der Waals interaction by the tolyl ring and/or polar interactions by the 2-amido group are responsible for proper anchoring of 2o to the sub-pocket of the binding site surrounded by Cys191, Phe192, Phe215, Val216, and Cys220.

Although 2q shows these nonspecific interactions with the sub-pocket binding site, the different orientation in the enzyme pocket caused by the H-bond interaction of the oxygen atom of the 5-carbonyl group involving the NH Gly193 (see above) could explain the lower inhibitory activity compared to 2o.

Stability and kinetic features

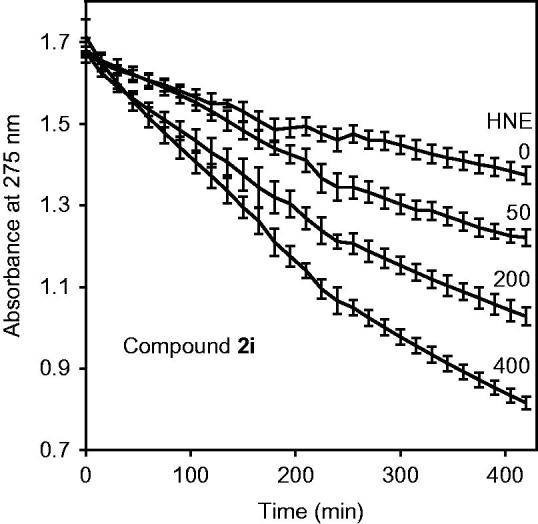

The most potent seven isoxazolones with IC50<100 nM were further evaluated for chemical stability in aqueous buffer using spectrophotometry to detect compound hydrolysis. The compounds had t1/2 values from 3.1 to 19.3 h for spontaneous hydrolysis (Table 3), indicating that these isoxazolones were more stable than our previously described HNE inhibitors with N-benzoylindazole scaffolds21,22. We also tested compound hydrolysis in the presence of HNE and found that the speed of hydrolysis gradually increased with increasing enzyme concentration. As an example, Figure 5 shows dose-dependent hydrolysis of compound 2i over time (Figure 5). In the presence of 400 mU/ml HNE, the hydrolysis was 2.2–4.8-fold higher than for spontaneous hydrolysis (i.e. without HNE) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Half-life (t1/2) for the hydrolysis of selected isoxazolone derivatives in aqueous buffer and in the presence of HNE.

|

t1/2 (h) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compd. | Max (nm)a | Spontaneous hydrolysis | In the presence HNEb |

| 2d | 290 | 7.7 | 3.5 |

| 2i | 275 | 19.3 | 4.0 |

| 2j | 285 | 5.3 | 2.1 |

| 2l | 275 | 19.3 | 4.3 |

| 2n | 285 | 6.2 | 2.6 |

| 2o | 290 | 8.9 | 3.4 |

| 2s | 285 | 3.1 | 0.9 |

Absorption maximum of the compounds for monitoring hydrolysis.

Hydrolysis was monitored in the presence of 400 mU/ml HNE.

Figure 5.

Analysis of compound 2i spontaneous hydrolysis. Compound 2i (80 μM) was incubated in 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.5, 25 °C) supplemented with 0, 50, 200, and 400 μg/ml HNE, as indicated. Spontaneous hydrolysis was monitored by measuring changes in absorbance at 275 nm (absorption maximum of compound 2i) over time. The data are presented as the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from one experiment, which is representative of two independent experiments.

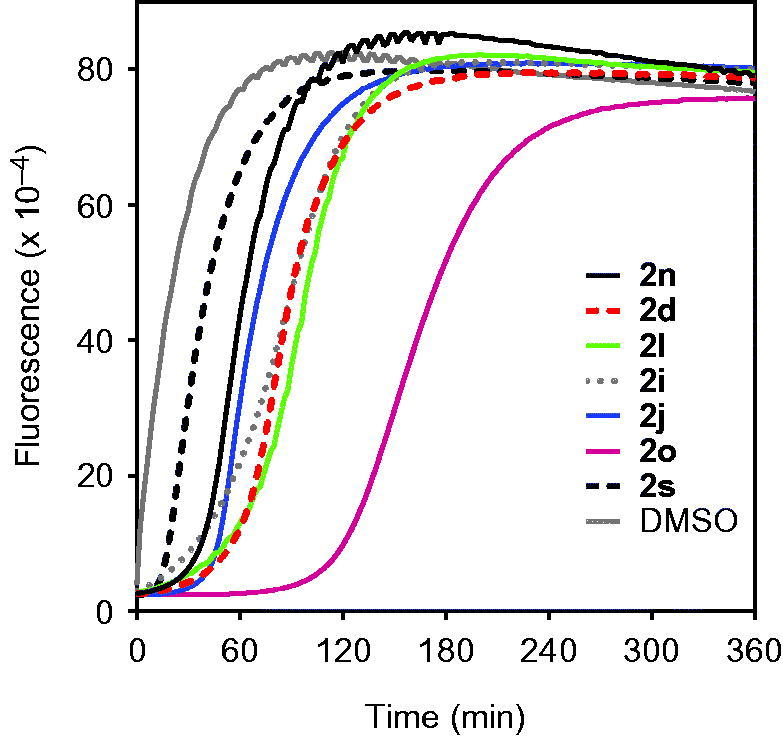

We also evaluated reversibility of the HNE-inhibitor complex over time for most potent compounds. As shown in Figure 6, HNE inhibition was maximal during the first 30 min for compounds 2n, 2d, 2l, 2i, and 2j. However, inhibition by compound 2s was reversed after 10 min. The most stable inhibition was found for 2o, where inhibition of HNE activity was reversed only after 2 h (Figure 6). To better understand the mechanism of action of this isoxazolone HNE inhibitor, we performed additional kinetic experiments. As shown in Figure 7, the representative double-reciprocal Lineweaver–Burk plot of fluorogenic substrate hydrolysis by HNE in the absence and presence of compound 2o indicates that this compound is a competitive HNE inhibitor.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of HNE inhibition by selected isoxazolone derivatives. HNE was incubated with the indicated compounds at 5 μM concentrations, and kinetic curves monitoring substrate cleavage catalysed by HNE are shown. Representative curves are from three independent experiments.

Figure 7.

Kinetics of HNE inhibition by compound 2o. Representative double-reciprocal Lineweaver–Burk plot from three independent experiments.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the isoxazolone nucleus is an appropriate scaffold for the development of potent HNE inhibitors. The most potent compounds were the 4-unsubstituted derivatives. In particular, compounds 2o and 2s, had IC50 values of 20 nM and 34 nM, respectively. Docking studies suggest that, differently from our previous N-benzoylindazoles compounds21,22, the attack of Ser195 is directed at the endocyclic C=O group at position 5 but also that the amidic C=O group is important for anchoring to the sub-pocket of the binding site surrounded by Cys191, Phe192, Phe215, Val216, and Cys220 through nonspecific van der Waals and polar interactions. This hypothesis is in agreement with the inactivity of the N-alkyl/aryl derivatives and the thioanalogues. Studies of chemical stability indicated that the new isoxazolones are more stable than the compounds we previously studied21–24, with t1/2 values from 3.1 to 19.3 h, and that they were competitive HNE inhibitors. Thus, this new class of HNE inhibitors has great potential for the development of potent and relatively stable HNE inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health IDeA Program COBRE Grant GM110732; USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch project 1009546; the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (project no. 4.8192.2017); University of Montana System Research Initiative: 51040-MUSRI2015-03; and the Montana State University Agricultural Experiment Station.

Disclosure statement

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health IDeA Program COBRE Grant GM110732; USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch project 1009546; the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (project no. 4.8192.2017); University of Montana System Research Initiative: 51040-MUSRI2015-03; and the Montana State University Agricultural Experiment Station.

References

- 1.Heutinck KM, ten Berge IJ, Hack CE, et al. . Serine proteases of the human immune system in health and disease. J Mol Immunol 2010;47:1943–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korkmaz B, Horwitz MS, Jenne DE, Gauthier F.. Neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3, and cathepsin G as therapeutic targets in human diseases. Pharmacol Rev 2010;62:726–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chua F, Laurent GJ.. Neutrophil elastase: mediator of extracellular matrix destruction and accumulation. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:424–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardoel BW, Kenny EF, Sollberger G, Zychlinsky A.. The balancing act of neutrophils. Cell Host Microbe 2014;15:526–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi SD, Voyich JM, Burlak C, DeLeo FR.. Neutrophils in the innate immune response. Arch Immunol Ther Exp 2005;53:505–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saitoh T, Komano J, Saitoh Y, et al. . Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate a host defense response to human immunodeficiency virus-1. Cell Host Microbe 2012;12:109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee WL, Downey GP.. Leukocyte elastase: physiological functions and role in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:896–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sifers RN.Intracellular processing of α1-antitrypsin. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2010;7:376–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoenderdos K, Condliffe A.. The neutrophil in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013;48:531–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gifford AM, Chalmers JD.. The role of neutrophils in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Hematol 2014;21:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Chen F, Zhai R, et al. . Plasma neutrophil elastase and elafin imbalance is associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) development. PLoS One 2009;4:e4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsushima K, King LS, Aggarwal NR, et al. . Acute lung injury review. Intern Med 2009;48:621–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cools-Lartigue J, Spicer J, Najmeh S, Ferri L.. Neutrophil extracellular traps in cancer progression. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014;71:4179–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sjö P.Neutrophil elastase inhibitors: recent advances in the development of mechanism-based and non-electrophilic inhibitors. Future Med Chem 2012;4:651–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucas S, Costa E, Guedes R, Moreira R.. Targeting COPD: advances on low-molecular-weight inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase. Med Res Rev 2013;33:E73–E101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwata K, Doi A, Ohji G, et al. . Effect of neutrophil elastase inhibitor (sivelestat sodium) in the treatment of acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern Med 2010;49:2423–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue N, Oka N, Kitamura T, et al. . Neutrophil elastase inhibitor sivelestat attenuates perioperative inflammatory response in pediatric heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Int Heart J 2013;54:149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stockley R, De Soyza A, Gunawardena K, et al. . Phase II study of a neutrophil elastase inhibitor (AZD9668) in patients with bronchiectasis. Respir Med 2013;107:524–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogelmeier C, Aquino TO, O’Brein CD, et al. . A randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-finding study of AZD9668, an oral inhibitor of neutrophil elastase, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with tiotropium. COPD 2012;9:111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Von Nussbaum F, Li VMJ, Allerheiligen S, et al. . Freezing the bioactive conformation to boost potency: the identification of BAY 85-8501, a selective and potent inhibitor of human neutrophil elastase for pulmonary diseases. ChemMedChem 2015;10:1163–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crocetti L, Giovannoni MP, Schepetkin IA, et al. . Design, synthesis and evaluation of N-benzoylindazole derivatives and analogues as inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase. Bioorg Med Chem 2011;19:4460–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crocetti L, Schepetkin IA, Cilibrizzi A, et al. . Optimization of N-benzoylindazole derivatives as inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase. J Med Chem 2013;56:6259–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giovannoni MP, Schepetkin IA, Crocetti L, et al. . Cinnoline derivatives as human neutrophil elastase inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2016;31:628–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crocetti L, Schepetkin IA, Ciciani G, et al. . Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of indole derivatives as deaza analogues of potent human neutrophil elastase inhibitors. Drug Dev Res 2016;77:285–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krogsgaard-Laersen P, Brogger Christensen S, Hjeds H.. Organic hydroxylamine derivatives. VII. Isoxazolyn-5-ones. Reaction sequence previously stated to give 3-hydroxyisoxazoles. Acta Chem Scand 1973;27:2802–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato K, Sugai S, Tomita K.. Synthesis of 3-hydroxyisoxazoles from β-ketoesters and hydroxylamine. Agric Biol Chem 1986;50:1831–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaguchi M, Takiguchi O, Tsukase M, Ishiwata Y.. Hair dye composition comprising azo dye. PCT Int Appl, WO2009005139 A2 20090108; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adembri G, Tedeschi P.. Synthesis and properties of 5-haloisoxazoles. Bull Sci Fac Chim Ind (Bologna) 1965;2–3:203–22. Chem Abstr 1965;63:13235b. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobsen N, Kolind-Andersen H.. 3-Hydroxyisoxazoles. PCT Int Appl, WO8401774 A1 19840510; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forist AA, Weber DJ.. Kinetics of hydrolysis of hypoglycemic 1-acyl 3,5-dimethylpyrazoles. J Pharm Sci 1973;62:318–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navia MA, McKeever BM, Springer JP, et al. . Structure of human neutrophil elastase in complex with a peptide chloromethyl ketone inhibitor at 1.84-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989;86:7–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters MB, Merz KM.. Semiempirical comparative binding energy analysis (SE-COMBINE) of a series of trypsin inhibitors. J Chem Theory Comput 2006;2:383–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CrysAlis RED Oxford Diffraction (version 171.34.41). Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK: Oxford Diffraction Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palatinus L, Chapuis G.. Superflip – a computer program for the solution of crystal structures by charge flipping in arbitrary dimensions. J Appl Cryst 2007;40:786–90. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheldrick GM.Phase annealing in SHELX-90: direct methods for larger structures. Acta Crystallogr A 1990;46:467–73. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrugia LJ.WinGX: an update. J Appl Crystallogr 2012;45:849–54. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mercury CSD 3.6 (Build RC6), Copyright CCDC 2001–2015. All rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elguero J, Marzin C, Katritzky AR, Linda P, eds. Advances in heterocyclic chemistry, supplement 1: the tautomerism of heterocycles. New York: Academic Press; 1976:656. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katritzky AR, Barczynski P, Ostercamp DL, Yousaf TI.. Mechanism of heterocyclic ring formations. 4. A carbon-13 NMR study of the reaction of β-keto ester with hydroxylamine. J Org Chem 1986;51:4037–42. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boulton AJ, Katritzky AR.. Tautomerism of heteroaromatic compounds with five-membered rings. I. 5-Hydroxyisoxazoles-5-isoxazolones. Tetrahedron 1961;12:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vergely I, Laugaa P, Reboud-Ravaux M.. Interaction of human leukocyte elastase with a N-aryl azetidinone suicide substrate: conformational analyses based on the mechanism of action of serine proteinases. J Mol Graph 1996;14:158–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.